Introduction

What Is This Book About?

This online textbook has two goals:

- To help readers find information in places, mostly online, where they usually don’t look;

- To help readers evaluate the credibility of the information they find.

Who Is This Book For?

Although we wrote this textbook for a required college-level journalism course, anyone who navigates information on the Internet can benefit from the concepts and skills presented here.

The primary audience for this book starts with students in Journalism 302: Infomania, a course we teach at the University of Kansas. When they take this class, these students usually are in their second or third semesters in the William Allen White School of Journalism and Mass Communications. They have varied career aspirations. A few of them want to be “traditional” journalists, writing for online news sites, magazines, or newspapers. Some of them want to be broadcast journalists. Many of them want to work in strategic communications, which encompasses public relations, advertising, marketing, and related fields.

Why Did We Write This Book?

The Journalism 302 course was conceived originally as an introduction to journalistic research methods. It is also a companion to a media writing course in which students learn the conventions of presenting the information they gather. The initial goal of the course was to teach students who do their research almost exclusively with Google and Wikipedia to become familiar with other information sources, like scholarly and business databases.

Journalism 302 also is designated by the university as a critical thinking course. This means that students are expected to reflect on their own thinking, to question their assumptions, and to support their arguments with evidence. Students are challenged to identify their own information needs, and to examine the credibility of their sources within the context of their current and future work as professional communicators.

Over time, and in conversations with colleagues at the University of Kansas Libraries, it became clear that Journalism 302 is an information literacy course. Information literacy, according to the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) definition, is about how individuals find information, understand its sources and structure, evaluate it critically, and use it responsibly (or don’t use it). Information literacy has been a key concern for library and information scientists for several decades. In our case, ACRL’s concept that the authority of information is constructed and contextual aligned well with the concept of credibility, which had become a unifying theme in the Journalism 302 course.

To teach information literacy and journalism practice, we needed a textbook that would deconstruct the process of judging the credibility or authority of sources, and that would align with the professional standards of journalism. As we searched for textbooks and other instructional materials, however, we concluded that there wasn’t anything on the market that met our students’ needs and the goals of this class.

This textbook, therefore, is the result of a collaboration between journalism and library faculty. It is an illustration of what happens when concepts developed in library science and instruction get applied to a specific field, in this case, journalism education. Our overarching intent in writing this book was to help undergraduate journalists develop the skills and a skeptical stance for accessing, evaluating, and using information, and in the process, to build their own authority as credible communication practitioners.

What Is in This Book?

The book is structured chronologically and topically, using the order in which concepts and skills are presented in the Journalism 302 course.

The first section focuses on the research process by breaking down the concepts and skills that are essential to assessing and contextualizing the authority of information. To begin, we define and explore the concept of credibility as it relates to practicing journalism. In the next chapters, we walk readers through the fundamentals of developing a topic, using search strategies, collecting evidence, and attributing the sources of information in writing.

Section 2 covers several approaches to evaluating the credibility of sources. We reinforce the link between evaluating sources and students’ own credibility, by encouraging students to approach every source with the question, “If I use this source in my writing, will it contribute to or diminish my own credibility?” Over four chapters, and a chapter on bias, we deconstruct and present several methods for engaging in the credibility assessment process. We provide step-by-step instructions and examples of identifying specific credibility cues, collecting evidence, conducting the assessment, and presenting a conclusion. Our methods are based on those presented in the 2017 online textbook, “Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers” by Mike Caulfield, and in the 2010 article, “Using a Targeted Rubric to Deepen Direct Assessment of College Students’ Abilities to Evaluate the Credibility of Sources” by Erin Daniels, published in the journal College & Undergraduate Libraries.

Section 3 focuses on several sources of information with which journalism and strategic communication students need to be familiar, and about which they need to develop a critical attitude. We begin where most students begin their research: with Google and Wikipedia. We discuss the limitations of Google and the dangers of its filter bubbles, in order to prompt students to advance their research beyond Google. In the Wikipedia chapter, students learn why an open-sourced encyclopedia is a good place to start but a bad place to stop, and how they can participate in improving Wikipedia. The remainder of the textbook covers news sources, public records, nonprofits as sources, information filed by public companies, research studies, data, historical sources, and interviews. In each of these chapters, we discuss how journalists and strategic communication practitioners use these information sources; we provide text and video instructions on how to access these sources and retrieve information from them; and we reinforce the process of assessing the credibility, or authority, of these sources.

Credibility is the thread that holds these sections together. As we argue in the first chapter, credibility is key to a journalist’s ability to produce trustworthy news and to a strategic communicator’s ability to represent and retain clients. Communicators establish their credibility by critically assessing their sources, and by using only the information that is credible enough to support their own credibility.

At the end of several chapters, testimonials from professionals who are alumni of our journalism school support the arguments presented. In suggested activities at the end to the chapters, we also invite students to apply their new knowledge, and to contribute to the textbook by developing tutorials about the book’s content. In the spirit of open pedagogy, we hope that with time, we will integrate these tutorials into the textbook’s chapters. By serving as contributors to this book, we hope that students will come to recognize themselves as credible creators and consumers of information.

Open Education

As we use this textbook in our class, we are inviting our students to contribute to it. Each semester, our students produce peer tutorials to accompany concepts and examples covered in the book. The first of these, below, provides tips for navigating and reading the textbook.

In addition to being featured in individual chapters, all of the student-produced tutorials are presented in the Appendix. We hope that with time, the book will be populated with timely and relevant videos produced by our students.

Peer Tutorial: Reading the Textbook

In this video, Jacob Allen (JOUR 302, spring 2019) discusses tips for getting the most out of the textbook.

Who Else Helped With This Book?

Several incredible colleagues helped us write this textbook. Our work began as a week-long Research Sprint, in which we were joined by Carmen Orth-Alfie and Callie Branstiter. During that week and throughout this project, Carmen and Callie generated insightful ideas, wrote content, and edited our writing. Their expertise in undergraduate learning and information literacy helped shape this textbook from beginning to end.

Roseann Pluretti assisted us as a project manager. The textbook’s production benefited from Roseann’s organizational skills, and from her practical experience teaching Journalism 302 five times as a Graduate Teaching Assistant.

We were grateful to receive an Open Educational Resources Grant from the University of Kansas Libraries, which partially funded the production and promotion of this textbook. Josh Bolick and Ada Emmet in the Schulenburger Office of Scholarly Communication & Copyright helped to inspire this textbook’s possibility and supported its creation.

Kerry Benson, Gerri Berendzen, Lisa McLendon, Eric Thomas and Scott Reinardy from the William Allen White School of Journalism and Mass Communications contributed content, editing assistance, and administrative support for this project. Jonathan Peters from the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia also contributed a chapter.

In the University of Kansas Libraries, Jamene Brooks-Kieffer, Caitlin Donnelly Klepper, Angie Rathmel, Marianne Reed and Paul Thomas offered ideas for content, wrote chapters, provided feedback on drafts, and assisted with the distribution and promotion of the textbook.

Short bios of all chapter authors are located at the end of the book.

We thank all the students in Journalism 302 and in other classes we have taught, whose work informed and filled the pages of this text.

What’s on the Cover?

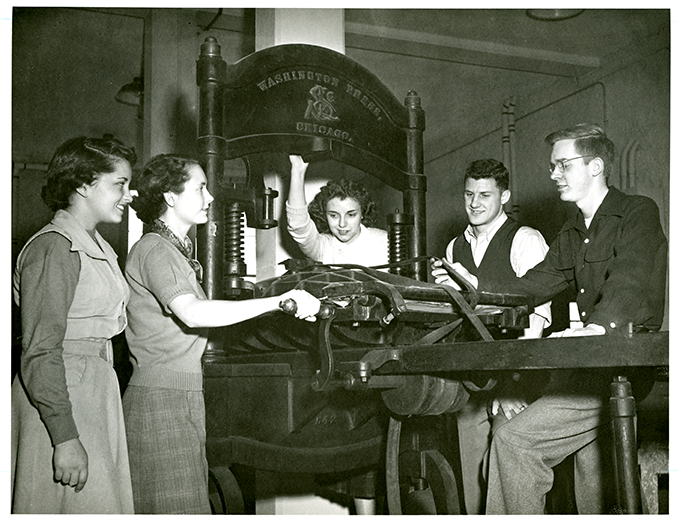

The cover photo comes from a folder of historical photos at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library that feature University of Kansas journalism students. It was taken in the early 1950s. An inscription on the back reads, “Students testing out the old Washington hand press in the typography lab, west end, 2nd floor, Flint Hall.” The press itself is now archived at the Spencer Research Library.

Only two of the five students pictured in the photo have been identified. Furthest left is Shirley Piatt (later Shirley Frizzell), KU class of 1954. She was one of the first women to serve as editor-in-chief of the University Daily Kansan, and went on to a career in public relations at Cessna, The Wichita Eagle, and Wichita State University.

Furthest right is Rich Clarkson, KU class of 1956, who became an award-winning sports photographer. The Clarkson Gallery, which is located in the west end of the first floor in Stauffer-Flint Hall at the University of Kansas, is named in his honor.

We hope that this book can help our students pursue fruitful careers as credible communications professionals, akin to their predecessors pictured in this photo.