5 Attribute All Sources

Kerry Benson

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Distinguish between primary and secondary, and human and nonhuman sources.

- Explain why and when attribution is necessary.

- Use proper mechanics of attribution.

- Embed links to online sources in digital text.

Ladybug Rock, by Mark Caton

My father, a Presbyterian minister, rarely used the King James Version of the Bible, so I remember vividly when he referenced the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Romans from the KJV.

Romans 13:7 reads: “Render therefore to all their dues: tribute to whom tribute is due; custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honour to whom honour.”

Because I was a child, the language of the passage confused me, and I asked my dad what it meant. He laughed before briefly summing up Paul’s message.

“It pretty much means you give people recognition for what they’ve done,” my dad said. “Like when your mom and I really liked the ladybug rock you brought home from school and you told us Mark Caton was the one who painted it. You gave Mark what was due to him, the credit for being the painter, instead of telling us you’d done it.”

Not everyone needs a biblical lesson on giving credit where it’s due. And credit isn’t necessarily an acknowledgment of excellence, as Mark Caton could have done a poor job of painting a ladybug on stone, but in journalism and strategic communications attribution is like that ladybug: a rock. It’s one of the ethical (and often lawful) foundations of a news or feature story, a documentary, a company news release, a digital ad, or a marketing PowerPoint.

This chapter will help illuminate the concept of attribution, why it matters, who uses it, who benefits from its use, when it’s used, and why professionals may disagree on its use. This chapter also will address how to journalistically cite sources, how attribution can go wrong, and where to find more on the topic.

What is Attribution?

Reputable and engrossing writing, whether it’s journalism or strategic communication, starts with responsible and principled research and reporting. Attribution is vital to all ethical reporting because it identifies information sources.

The Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications (ACEJMC), which accredits journalism schools, lists core values and competencies all graduates should be able to meet. Among those competencies is the ability to “demonstrate an understanding of professional ethical principles and work ethically in pursuit of truth, accuracy, fairness and diversity.” Attribution is key to the quest for veracity and transparency. Attribution’s job in journalism is to answer the “who” of a quotation, the “where” and “what” of background information, and –- sometimes –- the “how.”

Who said what? Where did reporters or editors get their data? What research was used to support an opinion? How did a human source provide those statistics?

Understanding attribution requires understanding sources.

Primary Sources

If a human contributes information for a story, whether it’s in-person, on the phone, or via email or text, that person is a source. The most credible human source is a primary one, a person with a direct connection to the information or situation pertinent to the story.

This first-hand relationship provides for an accurate telling of that person’s experience. Even though the source’s personal viewpoint can be an opinion, it can also provide a reporter with facts. It’s the reporter’s responsibility to confirm the facts. An exception to this is if the journalist is the witness to events. Journalists can’t name themselves as sources in articles.

Primary human sources also add what it sounds like –- humanness. They put a face to the facts and a person to the perspective. Often they can synthesize information in a way that makes it accessible and easy to understand for other people.

Any person who contributes any kind of information to a story is a human source, even if that material is never published or broadcast.

Primary human source examples:

Chadwick Boseman, star of the Disney and Marvel Studios film “Black Panther,” says in a 2018 interview with USA Today how respectful he is of the cinematic history the movie was about to make.

Infections, like the kind caused by what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention call “nightmare bacteria,” are drug-resistant and “virtually untreatable with modern medicine,” CDC Principal Deputy Director Dr. Anne Schuchat said in a press briefing.

The reporter in each scenario above indicates to readers or viewers where the information originates. The importance of primary source credibility is clear. The main actor in a film will know about acting in that film. Schuchat, who served as acting director of the CDC twice, will know the agency’s public health concerns and alerts.

A journalist could probably get the same information from a nonhuman source, but Boseman and Schuchat put a trustworthy human face to the communication they’re sharing.

Primary sources also can be nonhuman. Government records, reports of original research studies, and polls are examples of primary sources because they are the original locations of the information they contain. A nonhuman source is primary if it provides original information that does not cite other sources.

Some sources, like research studies, often are both primary and secondary sources, because they both re-state information found elsewhere, and are the original sources of other information.

Primary nonhuman source examples:

April is designated as Alcohol Awareness Month by the federal government. A journalist developing a story about drug and alcohol trends among seniors, or in a specific geographical region, might use data published by the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD), a primary nonhuman source.

Marketers at a major health care organization choose similarly to highlight the importance of alcohol awareness, and they also provide NCADD data in a story in their monthly e-zine or quarterly newsletter. NCADD serves as a primary nonhuman source. The marketers supplement their story with human primary sources from within their organization, such as physicians and counselors.

Journalists and strategic communicators should not leave their audience to question information or sources’ legitimacy. The exception is if something is a well-known –- or widely reported –- fact that’s reasonably indisputable.For example, it would not be necessary to cite a source for “Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, delivered what would come to be known as ‘The Gettysburg Address’ in November 1863.”

Secondary Sources

Both human and nonhuman sources also can be secondary sources, or research material. A secondary source is information containing others’ reporting and data gathering, and it’s usually information used for other purposes as well as a journalist or strategic communicator’s purposes.

Journalists must determine if the secondary source information is fact or opinion, or both, which they usually do by cross-referencing the information with other verifiable sources.

If a reporter looks to a website for background information, or reads other media reports on a story, it’s the reporter’s responsibility to go to the information’s original, or primary, source.

Avoid quoting The New York Times or Fox News as a source from their stories on obesity in the United States. Go to the primary source those media reference. If they cite a study, or data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), go to that study or to the CDC website. After verifying the information, cite the study or the CDC.

For example, a reporter working on an article about border crossings along the United States’ southern border sees a CNN report on a similar story, using data about who is crossing and where. The reporter should look for the source of the data, not CNN’s information. If the numbers are from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the reporter should go to CBP for its facts and figures, and cite it as the source.

Often journalists use secondary sources as a springboard to develop a story idea, including a single exposé, an in-depth series of articles or podcasts, or a documentary. From these secondary sources, they look for the primary sources of information, and use those in their reports.

When To Attribute?

The late journalist Steve Buttry, whose résumé included editor, reporter, newsroom trainer, and teacher of digital journalism, wrote the following in a blog post, “You can quote me on that: Advice on attribution for journalists”:

“Attribute any time that attribution strengthens the credibility of a story. Attribute any time you are using someone else’s words. Attribute when you are reporting information gathered by other journalists. Attribute when you are not certain of facts. Attribute statements of opinion. When you wonder whether you should attribute, you probably should attribute in some fashion.”

Buttry’s advice from the same post on when not to use attribution is shorter:

“Don’t attribute facts that the reporter observed first-hand: It was a sunny day. Don’t worry about attributing facts where the source is obvious and not particularly important and the fact is not in dispute.”

Journalists and strategic communicators who write or report factual information or opinions should attribute all those facts and opinions to a source. In some circumstances, attribution is particularly important. Attribute facts if controversy might surround them, such as when gun permit requests go up or down, or the number of middle-aged men addicted to opioids changes dramatically. Also, always attribute evaluative facts that depend on the rule of law, or facts that rely on an expert’s information.

In broadcast, reporters and podcasters should identify the source of any statement, particularly one of questionable accuracy. The source interviewed in a radio, podcast or videotaped segment must be identified at the start. The newscaster, reporter, or podcaster can identify with a sound bite before the source speaks.

With video, a source can be acknowledged verbally and with a lower third super, a graphic, usually the interviewee’s name and location, superimposed along the bottom of the screen.

Why Attribute?

Both journalists and strategic communicators use attribution to signal to their audiences that they’re reliable and sincere. It indicates that they’ve vetted the sources, which helps readers, listeners and viewers understand the information effortlessly, without having to stop and question the content’s accuracy and authenticity.

Journalists and strategic communicators benefit from using attribution, because the trust that their audience places in the sources they cite extends to the journalists and strat comm practitioners themselves.

Good attribution says to the audience, “You can trust me because the sources I use are trustworthy.”

Individual media companies underscore the importance of attribution in their values statements. According to The Associated Press, the goal of attribution is “to provide a reader with enough information to have full confidence in the story’s veracity.”

Attribution also lets the journalist or strat comm practitioner share or shift the responsibility for any information in a story. If a reader disagrees with something he or she sees in an article or report, attribution can take the heat off the journalist or strategic communicator who wrote the piece, and direct it toward the source of the information.

When a reader or viewer questions the veracity of some information, attribution says, “Blame the message source, not the messenger.”

Attribution also allows audience members to examine a topic further. By pointing to their sources, journalists and strat comm practitioners invite their readers and viewers to find those sources for themselves, and to take deeper dives into the topics they cover.

Attribution is like the entryway to Platform 9 3/4 in the Harry Potter books, from which readers can set off on their own journeys into the subjects that interest them.

Finally, attribution can be the antidote to journalism’s biggest transgressions of fabrication and plagiarism. A journalist or strat comm practitioner who points to his or her sources is less likely to have made up something, or taken credit for someone else’s words, than one whose sources are hidden.

There is sometimes a misguided perception that attribution is less important in strategic communication than it is in news and broadcast journalism.

The Public Relations Society of America, for one, opposes this view. It argues in its Ethical Standards Advisories — Best Practices, that despite the pressures of time and shortage of resources that all content creators face, public relations practitioners have a duty to disclose their sources:

“Public relations professionals may be … challenged when facing a deadline, an assignment in a new area or even the lack of a good idea and the easy solution may be to use someone else’s words or ideas. However, an ethical practitioner respects and protects information that comes into his or her possession and makes an effort to preserve the integrity of that information.

“An ethical practitioner also uses the works of others appropriately, with proper author/creator attribution. There are many ways to do this … including footnotes, parenthetical references to the original author or a reference to the original work within the text. When words are used verbatim, it is important that they be enclosed in quotation marks and the exact source of the quote be provided either within the text or in a reference section.”

These guidelines reflect the professional standards expected of all communications professionals.

How To Attribute?

How to select quotes is part of learning to build an article, newscast, or magazine story, but how to assign responsibility to quotes is part of understanding attribution.

Direct quotes

The following comes from guidelines used in the School of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of Kansas.

A direct quote must be exactly what a source says. Direct quotes should add zest to the story. Don’t use quotes to deliver boring-but-necessary facts or use quotes that don’t drive the story forward.

Direct quotes are used also for precision. An accurate direct quote can add confirmation of controversial facts.

It can convey a person’s information and attitude, which adds character and flavor to a story.

Examples of direct quotes:

“It’s just a job. Grass grows, birds fly, waves pound the sand. I beat people up,” boxer Muhammad Ali said.

“I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times, I’ve been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed,” basketball legend Michael Jordan said. “I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

“That’s all I could ever hope for, to have a positive effect on women. ‘Cos women are powerful, powerful beings,” singer Rihanna said. “But they’re also the most doubtful beings. They’ll never know – we’ll never know – how powerful we are.”

Say “no” to quotes that add nothing, such as “we’re so excited,” and “we went out there and did our best.” Obvious. Goofy. This may be difficult for strategic communicators whose bosses or supervisors may press for hyperbole. Resist. It damages credibility.

But journalists and strategic communicators often include direct quotes from public officials or company executives, even if what’s said doesn’t push the story forward or add flavor, because readers and viewers see those figures as authorities who should know what’s going on.

Paraphrasing

A paraphrase, or indirect quote, is a re-wording of what a source says. It must reflect the source accurately, even though it’s not relayed word for word. An indirect quote must not alter the meaning of what someone said.

In incorporating quotes into their writing, journalists often mix direct and indirect quotes.

This is the direct quote:

“When I first started teaching J101, I like, was happy to have – wow, like, 450 students, but then I had doubts,” Benson said. “But I wanted to teach many students at once. I thought I could teach that many. But, wow, managing a huge class is like turning a cruise ship in a hurricane.”

This is the paraphrase, or indirect quote:

Benson said she is happy to teach J101, a course with 450 students, but initially had doubts.

The writer could then use a partial quote to support the paraphrase:

She compared managing a class that size to “turning a cruise ship in a hurricane.”

Handling human quotes

When referring to information given by specific human sources, the verb in print is “said,” even if a writer isn’t directly quoting a source. “Said” is best because it can’t be wrong. If a source said something, the source spoke and said it. “Said” doesn’t stop thought when a reader sees it.

Verbs such as “explained” or “disclosed” or “exclaimed” require a reader to process differently. Such verbs draw attention to themselves and away from the content that matters. Readers have to think about each verb because those have connotations that “said” does not.

Weird verbs of attribution, such as argued, claimed, concluded, warned, urged and remarked, are just that, weird. Writers don’t want to imply meaning that might alter the larger article’s credibility. “Said” as a verb is neutral. It doesn’t hint at any meaning beyond its action.

Handling nonhuman quotes

“According to” is used to attribute information to nonhuman sources. Journalists and strategic communicators should use “according to” for documents, news releases, studies, statistical abstracts, infographics, or secondary sources in general.

In journalism and strategic communication, writers do not use in-text citations. That is, in journalism, there is no MLA, APA, or Chicago citation style. Save that for English, history, and political science research papers. In journalism, for in-text source identification, if it’s not “said,” it is usually “according to.”

As with “said,” there is no need to come up with different terms.

Examples of nonhuman attributions:

Teachers in the district make at least three times as much per year as teachers in other area school districts, according to state employment records.

According to a World Health Organization report, this season’s flu strain may infect millions worldwide.

Student athletes are graduating at rates twice as high as they were a decade ago, according to NCAA findings.

But that’s so repetitive

Journalists and strategic communicators, particularly if they hear their English composition teachers in their heads, may resist “said” or “according to” for every attribution in a story. They fear the repetitive use will make their writing dull and unvaried. But readers appreciate the ease of reading, so they’re not usually troubled by “said” or “according to.”

Attribution terms may vary by news organization or publication. Some journalists have the option to use alternatives, such as “stated” for human sources. Magazine writers often have the editorial leeway to use “says” – using present tense even if they’re attributing content a source provided in an interview a day, a week, or a month prior to publication. But writers can’t be wrong with “said” when attributing a human source.

Order matters

Attribution can work at the beginning of a sentence, but often is even better at the end of the sentence. This places the emphasis on the information first, then on the source.

Starting with the quote or paraphrase, and then providing attribution, is more interesting for readers than the other way around. Presumably, what a person is saying is more interesting than who’s saying it. If it’s a well-chosen quote, the information is what’s important or relevant, and the attribution is just for context and credibility.

Grammar notes

In English, writers usually put the verb after the subject in declarative sentences. Not always, but it keeps the emphasis on the subject. Remember, “Jesus wept.”

The order of name and verb is, when possible, name, then verb.

Correct example:

“The scientist examining the evidence couldn’t conclude the origin of the DNA,” Fontaine said.

Incorrect example:

“The scientist examining the evidence couldn’t conclude the origin of the DNA,” said Fontaine.

Exception example: When there’s a title or description that makes it awkward:

“The scientist examining the evidence couldn’t conclude the origin of the DNA,” said Elliot Fontaine, Colorado Springs police spokesman in charge of the investigation.

Incorrect exception example:

“The scientist examining the evidence couldn’t conclude the origin of the DNA,” Elliot Fontaine, Colorado Springs police spokesman in charge of the investigation, said.

Broadcast specifics

Broadcast attribution differs from print in several ways. Direct quotations are rare. Radio, television and podcast writers prefer indirect quotes or statement summaries.

Direct quotes, if used, should be preceded by a phrase such as “in his words” or “what she called.” Quotation marks should also be shown. They give broadcasters a clue, or signpost, to change their vocal pattern.

Broadcast example:

President Donald Trump says he will roll back all policies and laws from what he called “Obama’s clown car of a presidency.”

If it’s critical that a source be quoted directly, a broadcaster or writer may use sound bites, or actualities, in the audio. Attribution is always given before sources speak. It must be clear from the start that the quote is not the broadcaster’s thoughts or opinions.

With radio or podcasts, because listeners use only their ears to absorb the information, they need to know right away who’s responsible for what’s being said. It’s too cumbersome to inject “quote and unquote” into broadcast to indicate to listeners what is and isn’t a direct quote.

An identifier, such as a title, always goes before the name in broadcast.

Broadcast identifier example:

New York City Mayor Bill DeBlasio says he will support the new NYPD policy change on overtime pay.

With TV or video, the visual shows who’s making the statement, and a character generator super (or lower third) identifies the person after three or four seconds of video. The anchor or reporter may or may not identify the source by name in the introduction, but usually provides an identifier for context.

Broadcast lead-in example:

If the KU chancellor says,

“The number of both undergraduate and graduate students suffering from food insecurity rose 48 percent between 2015 and today.”

The broadcaster might lead into the sound bite with a synopsis: Chancellor Doug Girod says food insecurity is on the increase among students at KU.

In broadcast, source attribution and identification should be written conversationally. Think of it as the difference between a formal, engraved invitation delivered by the postal service and an e-vite via email or social media.

Be careful with pronouns. Again, because listeners and viewers can’t refer back easily in a video or audio story, they may not remember, “She? Who is she?” It’s better to repeat a name, office or title to prevent confusion.

Use “says” and not said, as if it’s happening now. “Says” is present tense and describes an ongoing action. But when broadcasters are speaking to something a source said in the past, “said” makes more sense.

Broadcast says/said example:

Chancellor Doug Girod says food insecurity is on the rise among KU students. Before he became chancellor, Girod said he would address food scarcity across campus.

Broadcast style also may allow for “according to” when using human sources. It may be a matter of news organization policy.

Embedding Links: Digital Attribution

The Internet allows journalists and strat comm practitioners to elevate their attribution game by embedding links in their work to the sources that are available online.

If you are producing content for digital distribution, link, link, link. Linking goes hand in hand with attributing online content, whether it’s news or strategic communication. Readers can –- even if they don’t –- click on links that provide background and full context to the cited information.

Linking is about transparency and trust with readers. Linking to sources in articles and reports increases the transparency of the journalists’ and strategic communicators’ work. It brings readers closer to the sources, encouraging them to verify the veracity of the information they are reading.

If attribution is like giving your friend an address to a restaurant, embedding a source’s link is like holding the restaurant’s door open for your friend when they arrive.

Any source that can be linked in an online article, should be linked. Not doing so can raise questions in an audience’s mind about why the source isn’t linked.

What Embedded Sources Look Like

Here are two examples of what embedding looks like in professional publications.

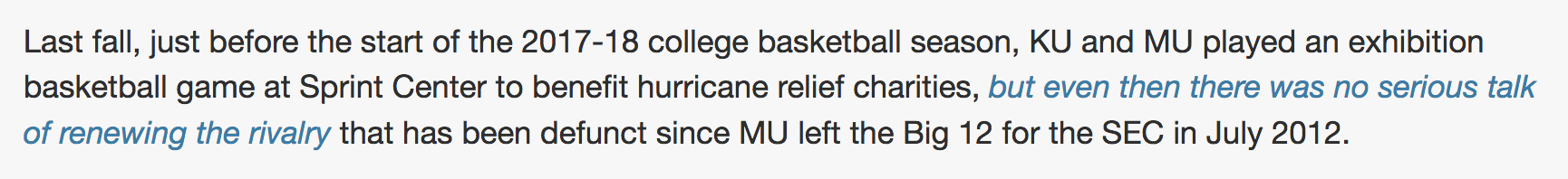

The following screenshot shows a paragraph in a Lawrence Journal-World, July 13, 2018, article titled “New Kansas AD Jeff Long addresses still-defunct KU-MU Border War.”

The link in the paragraph takes readers to an Oct. 22, 2017, article titled “Bill Self on playing Mizzou: ‘I don’t think there’s been any change in our position.’”

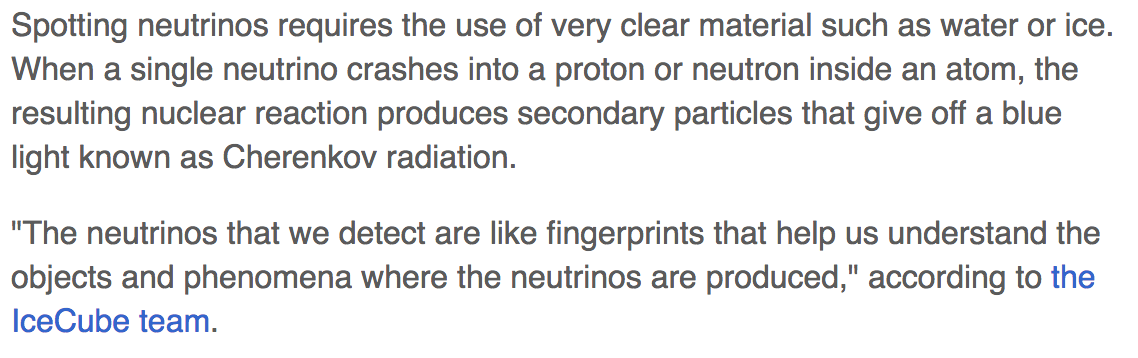

The next screenshot shows two paragraphs from a July 14, 2018, article, “IceCube: Unlocking the Secrets of Cosmic Rays,” published on the website Space.com.

The link in the second paragraph leads to a FAQ page on the website of the University of Wisconsin’s South Pole Neutrino Observatory.

The URLs for the articles presented above are:

http://www2.ljworld.com/weblogs/tale-tait/2018/jul/13/new-kansas-ad-jeff-long-addresses-still/, http://www2.kusports.com/news/2017/oct/22/bill-self-playing-mizzou-i-dont-think-theres-been-/

https://www.space.com/41170-icecube-neutrino-observatory.html, https://www.space.com/, https://icecube.wisc.edu/about/faq

But the professional examples do not show their readers these strips of URL code.

This is because a name or description that identifies exactly where readers are going when they click on the link is more welcoming than an incomprehensible string of code. A linked snippet of text gives readers the ability to choose their web source with confidence, and it looks much more professional than raw URL.

How to Embed Links to Online Sources

You probably already are familiar with inserting source links into documents, emails, social media posts, or presentations by copying and pasting the URLs of the sources. It takes eight steps to embed a link (also called a hyperlink) in text.

- Browse to the source’s webpage.

- At the top of the browser, locate the URL field (URL stands for “uniform resource locator”).

- Highlight the entire URL and copy it (Command+C, or Control+C, or Edit > Copy).

- In the document you are writing, write a statement that will serve as the link. It could be a descriptor, such as KU J-School Technology, or it could be more directive and fun, such as Start here to learn how best to use your technology.

- Highlight the text you just typed.

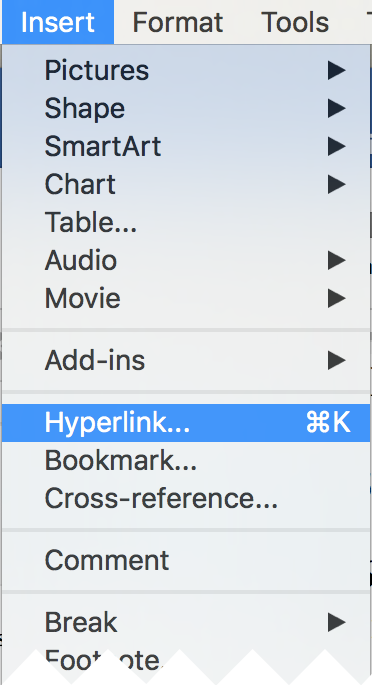

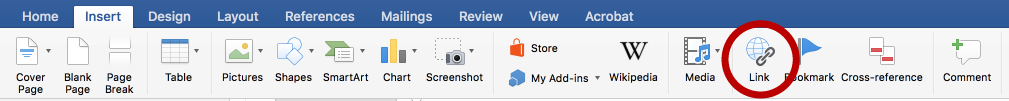

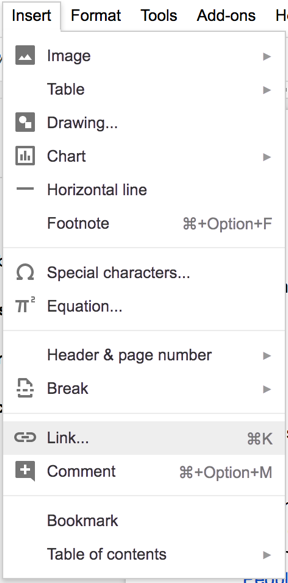

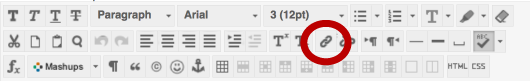

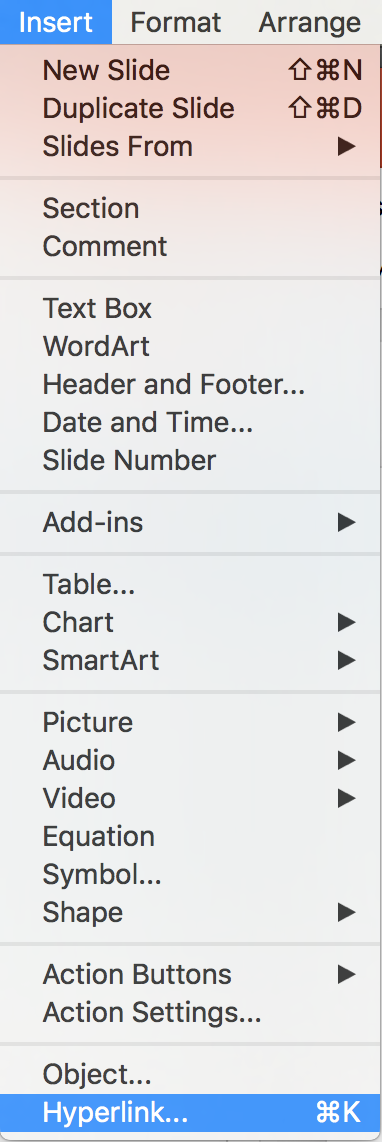

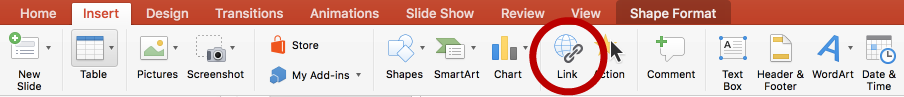

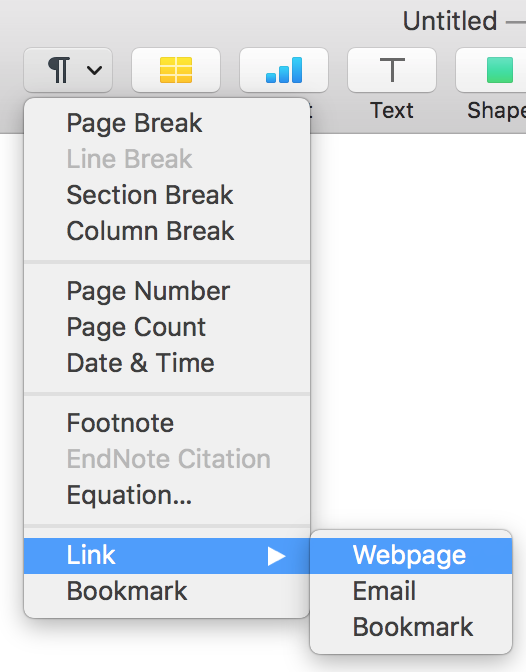

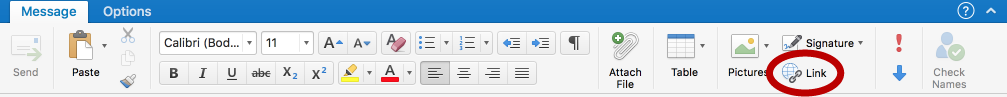

- Use the “insert hyperlink” tool in the platform you are using. Here are some visual examples of where to find these tools. The link tool often is represented graphically with two links of a little chain.

Word:

Google Doc:

Blackboard:

PowerPoint:

Pages:

Outlook:

- In the dialog box that appears, paste the source URL into the appropriate field. Oftentimes, you will see the text you highlighted in this box as well.

- Test the link using a different browser or computer than you used originally. This is especially important for links that originate behind paywalls.

What If a Source Wants To Remain Anonymous?

Avoid using unidentified sources for news or strategic communication documents. But this might depend on newsroom or organization policy. It’s usually not acceptable, as trust and transparency are the agreement readers, viewers, and listeners have with media content providers.

Exceptions are sometimes made when the only way to get a story is to offer a source anonymity. It shouldn’t be given lightly and without understanding that the information must still be reliable and accurate.

Reasons to offer anonymity could include a situation where by providing a name, the source would suffer public humiliation, lose a job or position, or go to jail.

If an anonymous source must be used, offer as much detail as possible about the source and explain the reason for anonymity.

For example, name a source as “a university official with ties to the administration who requested anonymity because his superiors had ordered him not to speak publicly or he would lose his position.”

When a source requests anonymity, get the source’s name and contact information, just in case an editor needs it.

The following are examples of ethical codes and policies journalists follow when deciding to use anonymous sources or pseudonyms.

Under Associated Press rules, material from anonymous sources may be used only if:

- The material is information and not opinion or speculation, and is vital to the news report.

- The information is not available except under the conditions of anonymity imposed by the source.

- The source is reliable, and in a position to have accurate information.

The Society of Professional Journalists published a position paper on anonymous sources:

- Identify sources whenever feasible. The public is entitled to as much information as possible on sources’ reliability.

- The most important professional possession of journalists is credibility. If the news consumers don’t have faith that the stories they are reading or watching are accurate and fair, if they suspect information attributed to an anonymous source has been made up, then the journalists are as useful as a parka at the equator.

- To protect their credibility and the credibility of their stories, reporters should use every possible avenue to confirm and attribute information before relying on unnamed sources. If the only way to publish a story that is of importance to the audience is to use anonymous sources, the reporter owes it to the readers to identify the source as clearly as possible without pointing a figure at the person who has been granted anonymity. If the investigating police officer confirms John Doe has been arrested, the officer is a “source in the police department” and not even a pronoun should point to the gender.

The Washington Post Standards and Ethics: Policy on Sources and Confidential Sources

- The Washington Post is committed to disclosing to its readers the sources of the information in its stories to the maximum possible extent. We want to make our reporting as transparent to the readers as possible so they may know how and where we got our information. Transparency is honest and fair, two values we cherish.

- Sources often insist that we agree not to name them before they agree to talk with us. We must be reluctant to grant their wish. When we use an unnamed source, we are asking our readers to take an extra step to trust the credibility of the information we are providing. We must be certain in our own minds that the benefit to readers is worth the cost in credibility.

- In some circumstances, we will have no choice but to grant confidentiality to sources. We recognize that there are situations in which we can give our readers better, fuller information by allowing sources to remain unnamed than if we insist on naming them. We realize that in many circumstances, sources will be unwilling to reveal to us information about corruption in their own organizations, or high-level policy disagreements, for example, if disclosing their identities could cost them their jobs or expose them to harm. Nevertheless, granting anonymity to a source should not be done casually or automatically.

- Named sources are vastly to be preferred to unnamed sources. Reporters should press to have sources go on the record. We have learned over the years that persistently pushing sources to identify themselves actually works—not always, of course, but more often than many reporters initially expect. If a particular source refuses to allow us to identify him or her, the reporter should consider seeking the information elsewhere.

- Editors have an obligation to know the identity of unnamed sources used in a story, so that editors and reporters can jointly assess the appropriateness of using them. Some sources may insist that a reporter not reveal their identity to her editors; we should resist this. When it happens, the reporter should make clear that information so obtained cannot be published. The source of anything that is published will be known to at least one editor.

- We prefer at least two sources for factual information in Post stories that depends on confidential informants, and those sources should be independent of each other. We prefer sources with firsthand or direct knowledge of the information. A relevant document can sometimes serve as a second source. There are situations in which we will publish information from a single source, but we should only do so after deliberations involving the executive editor, the managing editor and the appropriate department head. The judgment to use a single source depends on the source’s reliability and the basis for the source’s information.

- We must strive to tell our readers as much as we can about why our unnamed sources deserve our confidence. Our obligation is to serve readers, not sources. This means avoiding attributions to “sources” or “informed sources.” Instead we should try to give the reader something more, such as “sources familiar with the thinking of defense lawyers in the case,” or “sources whose work brings them into contact with the county executive,” or “sources on the governor’s staff who disagree with his policy.”

How To Attribute Information From an Email, a Text, or a Social Media Post?

If a credible source responds to an interview in an email, attribution should indicate this.

Email attribution example:

The CEO of Mosette Healthcare Group, Lana Dunham, wrote in an email that she plans to merge the group with St. Catherine’s Health Systems.

Social media posts are tricky and should serve primarily as story ideas to pursue.

According to National Public Radio’s ethics handbook, social platforms can serve as good newsgathering tools, but NPR said that it:

“requires the same diligence we exercise when reporting in other environments. When NPR bloggers post about breaking news, they do not cite anonymous posts on social media sites — though they may use information they find there to guide their reporting. They carefully attribute the information they cite and are clear about what NPR has and has not been able to confirm.”

Also, social media users aren’t always who they say they are, which poses a verification problem. If it’s reasonably possible to identify an account and the posts or tweets coming from it, use something like this to attribute:

Social media example

Illinois Senator Tammy Duckworth, who gave birth to her second child on April 9, tweeted on April 19: “May have to vote today. Maile’s outfit is prepped. Made sure she has a jacket so she doesn’t violate the Senate floor dress code requiring blazers.Not sure what the policy is on duckling onesies but I think we’re ready”

Tweeted, posted, shared. Use the appropriate attribution verbs for their social platforms.

How To Attribute a File, Archive or Stock Photo or Video?

It must be attributed to its original source. Include the title, author, source and date it was accessed.

Example:

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Farmhouse and family of resettlement client. Waldo County, Maine.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed April 19, 2018. NYPL Digital Collections

Attribute any Creative Commons photos or video by identifying the title of the work, the author or creator, the source (where it’s found) and license type. All Creative Commons work has a license type, which must be acknowledged.

Find specifics about CC attribution best practices here: Creative Commons attribution guidelines

To identify the digital rights of an image, use a search, such as the one developed by the Visual Resources Association: Image search resource

News Releases

Reproducing news releases – either sent or gathered from a website – has been a lively topic in nearly all news centers that use releases and among all organizations and businesses that send or post them.

Raymond James attorney and KU alum Ellyn Angelotti Kamke wrote about attribution and its squishy spots for The Poynter Institute. In a 2013 article, Kamke addressed the sometimes-disputed issue of plagiarism-without-attribution in which some journalists view verbatim news release use.

In her article, Kamke raised the question many in the industry ask frequently, “How should journalists use and attribute information that comes from an official source via press release, a prepared statement an official social-media account or some other widely distributed avenue?”

Attribute. Attribute. Attribute. For transparency and credibility. Attributed material, Kamke wrote, “even when it comes from an official source, gives the audience more context about that information and how it was acquired by the writer.”

Strategic communicators, such as those specializing in public relations, want their material used and more often than not put the research and good writing into a news release so it’s fit for immediate publication with minimal editing. But even PR professionals see the value of readers knowing the sources and making their own decisions about their veracity.

Peer Tutorial: Attribution Review

In this video, Maggie Gould and Paige Moyer (JOUR 302, fall 2018) review the key types of attribution.

A Practitioner’s View

Mike Miller

B.S., KU Journalism, 2000

Senior Director, Editorial, NBC Sports Digital

NBC Sports Digital, including flagship sites NBCSports.com, Rotoworld and ProFootballTalk, serves a sports audience that craves sports news and analysis. How do we do that? We do some original reporting and we rely on extensive story aggregation.

Any story that isn’t reported by our writers is explicitly credited and linked to high up in the story, sometimes in the initial graf. Our editorial standard is that we don’t do lengthy excerpts or extensive quoting (why reproduce what the original story already has?), because we don’t want any confusion as to where the original story originates.

Excerpts are italicized, set off with quotes, or both. It should clearly be separated from the rest of the story.

For us, this places the onus on our writers to extend that aggregated story with a specific editorial take or analysis that drives the story forward. If we can’t break the story, we tell our audience why it’s important, which helps the original story’s credibility (we create awareness) and gives us some authority through analysis.

Activity 1: Search

Locate a recent news article or press release. Evaluate what source types — primary and secondary, and human and nonhuman sources — the author consulted and how the author cited these sources. Does the author follow the practices recommended in this chapter? If not, specifically how could the article or press release be improved? Summarize your suggestions in one or two paragraphs.

Activity 2: Credibility check

Find a published piece from the Associated Press or The Washington Post that cites an anonymous source. After reading the piece, consider if the use of an anonymous source followed the publication’s policy on granting anonymity to sources and if the use of an anonymous source affected the credibility of the author, the article, or the publication. Summarize your findings in one or two paragraphs.