20 Public Companies

Peter Bobkowski

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Define and identify public companies.

- Explain why public company filings are worth locating and reading.

- Evaluate the credibility of public company filings.

- Access and read a company’s 10-K and DEF 14A documents.

Toys Are No Longer Us

Businesses can be important sources of information about themselves, and about the industries and markets in which they operate. What a business does and says about itself affects many people, from consumers and employees to shareholders and those who work for companies that support it. Business news can be big news.

The March 2018 announcement that Toys “R” Us would close all of its U.S. stores is a good example of this. The news generated journalistic writing focused on Toys “R” Us employees, empty big box store spaces, toy manufacturers, competition among toy retailers, and independent toy stores. Behind the scenes, strategic communications practitioners probably researched the toy chain’s bankruptcy for lessons that would benefit their clients in the toy and large retail sectors, or in customer and shareholder relations.

In doing their research, both journalists and strategic communicators had a lot of information to work with. What led up to the Toys “R” Us demise was documented in many public documents that the company is legally required to publish about itself.

In the public records chapter, we discussed how to access public records about companies that do business in a specific state. Every company, from a mom-and-pop shop to a conglomerate, must register with the state in which it’s located. State filings are a good place to start when establishing the ownership of a business. But these state records are limited, usually containing little more than the owners’ names and their addresses.

In this chapter we focus on the information disclosed by large, publicly traded companies in their filings to the federal Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Throughout this chapter, we refer to these documents as public company filings. We start our discussion with the crucial distinction between public and private companies.

Public and Private Companies

A public company is one whose stock is traded on the stock exchange. This means, theoretically, that anyone can buy a piece of the company in the form of stock. A public company is public because members of the public (like you and me) can invest in the company.

But investment is risky. Public companies, meanwhile, have an interest in motivating potential investors to buy their stock. To protect the public (that is, us) from making misguided investment decisions, the federal government, through the SEC, requires public companies to disclose a considerable amount of information about themselves. This lessens public companies’ ability to misinform potential investors about the risks involved in buying their stock.

From our perspective as researchers, public companies are really great because there is a lot of freely available information about them.

Private companies, on the other hand, are not very transparent because, unlike public companies, they are not required to disclose much information about themselves. Private companies are owned by private individuals, and shares in these companies are not available for purchase by the public. These companies may have investors, but their stock is not traded publicly on the stock exchange. For this reason, the public does not need to know as much about private companies as we do about public companies.

Many of the businesses we deal with on a day-to-day basis are private companies. Our favorite local coffee shop, like La Prima Tazza? Private. Grocery stores, like Checkers or HyVee? Private. Favorite local restaurant, like The Burger Stand? Private. Corner gas station and convenience store, like Kwik Shop? Private. But this doesn’t mean that all private companies are small or local. Some of the largest companies around are private. For example, the largest employer in Kansas, Koch Industries, is a private company.

On the other hand, we also frequently do business with public companies. Starbucks, Dillon’s (or Kroger), McDonald’s, and Phillips 66 are all public companies.

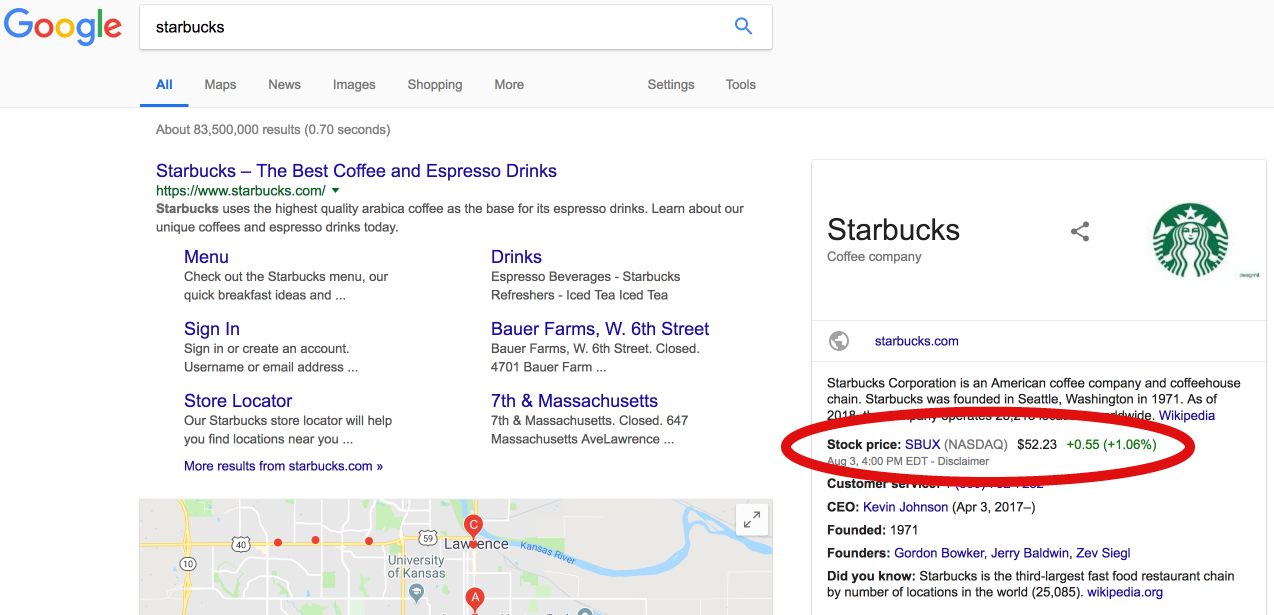

So how do you tell the difference between a private company and a public company? Recall that a public company’s stock is traded on the stock exchange, whereas a private company does not offer its stock for purchase. While most of us might not know much about investments, one visual cue we may associate with investments is the ticker symbol. Ticker symbols are abbreviations of public company names that represent the companies’ stock on the stock exchange. Starbucks is SBUX, Kroger is KR, McDonald’s is MCD, and ConocoPhillips is COP. Ticker symbols and stock prices scroll at the bottom of cable business channels like CNBC and Fox Business. Private companies do not have ticker symbols.

One way to figure out if a company is public or private, therefore, is to Google the company’s name and look for that company’s ticker symbol. Google provides company summaries to the right of its search results. Summaries of public companies include ticker symbols and their stock prices.

In the screenshot below, the circled text in the sidebar of Google results for Starbucks is the company’s ticker symbol and stock price. A private company search results would not include this information.

Once we know that a company we are interested in is a public company, we can forge ahead to unearth troves of public information about it.

Why Look for Public Company Filings

First, public company filings are relatively easy to research. The SEC is very specific about the information that it requires public companies to disclose, in what order and format this information needs to be presented, and how frequently it needs to be disclosed. This means that researching this information can be fairly straightforward: We know what information to look for, where to look for it, and when it will be updated next. This makes specific details about public companies relatively easy to pinpoint.

Second, public company documents are primary sources of information about individual companies. There is an industry of secondary sources, such as investment advisors and business information aggregator websites, which make a profit from this freely available information by repackaging it and presenting it in digestible chunks. Websites like Bloomberg, Yahoo Finance, and D&B Hoovers, for instance, offer reports about individual public companies using information they cull from these companies’ public disclosures. While these can be good sources of background information, as information experts, we need to know where this information comes from and how to access it so that we can verify this information for ourselves and, maybe also, make a profit from it.

Third, smart, real people read these documents. For example, Steve Ballmer, former chief executive of Microsoft and owner of the LA Clippers, said this in a New York Times article about how he learns what companies are up to:

“You know, when I really wanted to understand in depth what a company was doing, Amazon or Apple, I’d get their 10-K and read it. … It’s wonky, it’s this, it’s that, but it’s the greatest depth you’re going to get, and it’s accurate.”

A 10-K, as we will soon learn, is a public company’s annual report.

In sum, public company disclosures are relatively easy to access and read, they constitute primary source information, and successful people read them all the time.

How Credible Are Public Company Filings

When assessing the credibility of public company filings, at least two elements contribute to these documents’ credibility: their regulated nature and their position as primary sources. What can detract from the credibility of these documents is the self-enhancing and euphemistic language that companies can use to avoid being brutally honest in describing themselves.

Companies have strong incentives to provide accurate information in their disclosures. The SEC requires that public company filings include specific sections, that each section discusses particular business details, and that financial information follow precise accounting standards. The 10-K Annual Report, for example, is a document that every public company has to file once a year. This list discusses the sections that every 10-K needs to contain, the order in which these sections are to be presented, and what each section is supposed to cover.

The SEC oversees public company disclosures, and periodically evaluates and audits whether companies are complying with their disclosure requirements. Failure to disclose can result in various levels of reprimand, from a discussion with the auditors, to a formal investigation, to litigation, and to the suspension of trading. A public company does not want to be investigated, reprimanded, or suspended by the SEC because this generates negative news and can result in investors selling the company’s stock, thus devaluing the company.

For these reasons, there is a high likelihood that the information presented in public company filings is accurate.

The other element that contributes to the credibility of public company filings is the primary source nature of these filings. It’s worth it to reiterate a point we made earlier. There are many secondary business news sources that rely on, in large part, public company filings to generate narratives about the financial well-being of these companies, and to articulate projections for how these companies will be doing in the future. A quote from a primary document is more credible than a quote from a secondary document that quotes the primary document. The lessons we learned from playing telephone should help us appreciate the credibility of public company filings over the credibility of reports about public company filings.

Can anything detract from the credibility of public company filings? Sometimes the text of the filings, written by strategic communication practitioners who work in a company’s investor relations division, can lower the credibility of these filings. As much as the 10-K or another document is regulated by the SEC, there is considerable room for this document to present a somewhat biased version of reality. When reading a public company filing, it is useful to consider how the information presented in the document matches other reporting on the issues being discussed.

To illustrate how the language of a public company filing might undermine its own credibility, let’s consider how Chipotle’s 2017 10-K Annual Report discussed the food safety issues with which the company had been dealing. Here’s what the company said about its recent food safety incidents:

During late October and early November 2015, illnesses caused by E. coli bacteria were connected to a number of our restaurants, initially in Washington and Oregon, and subsequently to small numbers of our restaurants in as many as 12 other states. During the week of December 7, 2015, an unrelated incident involving norovirus was reported at a Chipotle restaurant in Brighton, Massachusetts, which worsened the adverse financial and operating impacts we experienced from the E. coli incident. As a result of these incidents and related publicity, our sales and profitability were severely impacted throughout 2016. In July 2017, cases of norovirus associated with a Chipotle restaurant in Sterling, Virginia had a further adverse impact on our sales, particularly throughout the mid-Atlantic and Northeast regions. The significant amount of media coverage regarding these incidents, as well as the impact of social media (which was not in existence during many past food safety incidents involving other restaurant chains) in increasing the awareness of these incidents, may continue to negatively impact customer perceptions of our restaurants and brand, notwithstanding the high volume of food-borne illness cases from other sources across the country every day. As a result our sales may not return to levels we were achieving prior to late 2015.

How many people got sick after eating Chipotle in 2015? Well, the annual report doesn’t tell us this. Was this a conscious omission by the annual report’s writers? That’s not clear. What does seem clear in this report is that Chipotle is most concerned about its customers’ perceptions of their food safety, and that it largely attributes these perceptions to negative media and social media coverage. There is a subtle subtext in this narrative suggesting that the food-borne illnesses attributed to Chipotle were not as big a deal as they were made out to be in the media.

So, how many people got sick? Ten? Twenty? Fewer than 50?

According to the website Food Safety News, which compiled information from county and state health departments, the two food safety outbreaks mentioned in Chipotle’s annual report accounted for nearly 200 people getting sick. But there also were three additional food safety outbreaks in 2015 that health officials linked to Chipotle. These three outbreaks did not receive wide media coverage and Chipotle did not even bother mentioning them in its annual report. How many people got sick in these under-reported outbreaks? More than 300. That’s a total of about 500 people getting sick after eating Chipotle in the second half of 2015.

Does 500 people over six months getting sick after eating at one restaurant chain seem like a large number? To me, it does, and if I was a potential investor and saw that number in the company’s annual report, it would give me pause. By avoiding specifics about the number and scale of these outbreaks, the annual report writers do appear to minimize the perception of the problem. While this narrative is not misleading, it does not present fully the scope of the problem. What does this do to the overall credibility of the report?

One more quick, related example. In the paragraph that immediately follows the one cited above, the writers continue the theme of identifying factors that can contribute to Chipotle losing revenue from lapses in food safety. In the previous paragraph, these factors included consumer perceptions and social media. In the following paragraph, notice the clever way in which the company’s food safety problems are equated with its greatest selling point, that is, its fresh ingredients and conventional cooking methods. (Also notice that this whole paragraph is one long sentence, and never aspire to write like this.)

Although we have followed industry standard food safety protocols in the past, and over the past two years have enhanced our food safety procedures to ensure that our food is as safe as it can possibly be, we may still be at a higher risk for food-borne illness occurrences than some competitors due to our greater use of fresh, unprocessed produce and meats, our reliance on employees cooking with traditional methods rather than automation, and our avoiding frozen ingredients.

The implication of this paragraph seems to be that the risk of contracting a food-borne illness is higher when eating food prepared with fresh, unprocessed, unfrozen ingredients and with conventional cooking methods, than when eating food from unfresh, processed, and frozen ingredients, and automated cooking. Whether that’s true or not can be debated. Framing a liability in terms of the company’s greatest asset is a masterful slight-of-hand. The message seems to be, “Hey, the deck is stacked against Chipotle. That’s what we get for trying to be super-wholesome.” How does such defensiveness relate to the report’s credibility?

In sum, are public company filings credible? For the most part, probably. The information contained in these filings tends to be accurate because companies do not want the SEC to come after them and hurt their stock prices. Plus, it’s primary source information, which is more credible than secondary source information. But companies also can engage in self-enhancement in these filings, which can detract from their overall credibility. Companies in these documents want to present themselves in the most positive light within the limits of what the SEC requires them to disclose.

How to Find Public Company Filings

There are two places online where we can find public company filings. The first is a company’s website. Public companies designate sections of their websites to investor relations. Oftentimes, these sections feel very different from these companies’ main, public-facing web pages or apps. This is because the goal in these sections is to come across as serious, transparent, financially responsible companies worthy of investment.

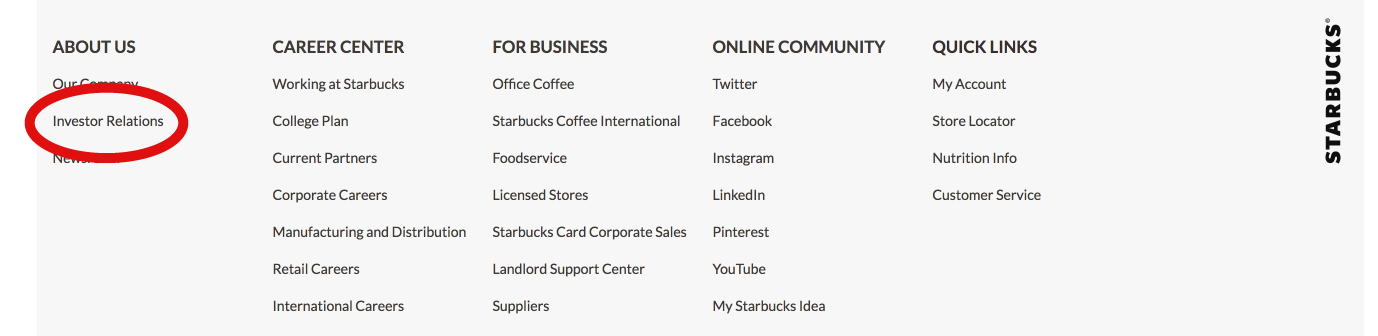

To access this section on a public company’s website, look for a link at the top or bottom of the company’s main page that says “Investor Relations.” Alternately, you might need to look for an “About Us” or “Company” link, and then look for an “Investor Relations” link on that page. Once there, look for a link that says “Financial Information” or “SEC Filings.”

The screenshot below shows the footer of the Starbucks website, with the Investor Relations link circled in the “About Us” column.

Most public companies will post on their websites the main documents they file with the SEC. Company websites also might include other financial information that’s not required by the SEC. When doing research on a public company, it’s good practice to read through these documents.

The second place to find public company filings is EDGAR, the SEC’s database. The following video walks you through how to find and use this database.

Three public company filings tend to be the most informative as we begin learning about a company, the 10-K, the 10-Q, and the DEF 14A.

The following video will help you navigate through, and find the most important information in the 10-K and DEF 14A documents:

If you are researching a public company that’s owned by an international company, such as Anheuser-Busch, these companies have different disclosure requirements than American companies. The equivalent of the 10-K for such companies is called the 20-F. These companies do not file quarterly reports or a proxy statement.

Peer Tutorials: EDGAR and DEF 14A

In this video, Abby Matchinsky and Anessa Saladino (JOUR 302, fall 2018) demonstrate how to determine if a company is public, and how to access a company’s documents in EDGAR.

In the next video, Cayden Fairman discusses implicit corporate bias in a DEF 14A filing.

A Practitioner’s View

Catherine Prestoy

KU Journalism Minor, 2019

Research Analyst

Bowersock Capital Partners

I gather financial data about our clients and their financial standing, including what they expect to receive in Social Security and what assets they have. I synthesize this information into a very easy-to-understand format. I also research securities, equities, stocks and mutual funds.

When it comes to company filings, I look at annual reports or Forms 8-K. They give me useful information on what’s going on with a company. I first read the form’s abstract version, to see what the company is trying to say about itself. I compare that to the quantitative parts of the report.

By paying close attention to the report, it’s easy to figure out what the company is trying to insinuate and what it is trying to sugarcoat. There are also many people on the internet that analyze and interpret what eachreport is saying. Major news sources cover what big companies say in their annual reports. I check my reading against what sources like the Wall Street Journal and The New York Times are saying about how those companies are doing.

It is important to understand how a company views itself and how a company wants to speak to its investors. An annual report will show what a company’s values are, what it’s trying to tell you and what it’s trying to not tell you. These words are coming directly from the people our clients may give their money to, trusting that they will get a return. It’s important for me and our clients to understand how each company views itself.

Activity 1: Is it public?

If a company is public, they should post their annual report to their website. This transparency is a great indicator of credibility. For this activity, locate one public company’s annual report. How did you find it? Was it posted to the public company’s website or did you have to use another resource, such as the ones discussed in this chapter? How does your search process affect your opinion of the company’s credibility?

Activity 2: What’s really in a 10-K?

After reviewing the guidelines for reading a 10-K, locate and read one public company’s annual report. Is there anything important or surprising in the 10-K? Based on the 10-K, how credible do you think the company is?