14 Open Records and the Freedom of Information

Jonathan Peters

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Determine which public records are readily available to you.

- Define the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

- Access public record using the provisions of FOIA.

FOIA at Work

“German Bosque’s personnel file looks more like a rap sheet than a résumé,” the Miami Herald-Tribune reported. When you are a cop, this is not a good thing.

The Herald-Tribune uncovered flaws in Florida’s Internal Affairs agency, which is charged with “policing the police.” After obtaining Bosque’s personal file from his police department, Herald-Tribune reporters were able to piece together why the system had failed to protect the citizens of Opa-Locka, Florida, from a police sergeant with a violent and criminal past.

Bosque had retained his post despite undergoing 40 internal reviews for misconduct, including 16 instances of battery or excessive violence. Bosque also was “fired five times and arrested three, he was charged with stealing a car, trying to board an airplane with a loaded gun and driving with a suspended license.” Kind of unbelievable, huh?

Well, to prove their credibility, the reporters uploaded each relevant piece of Bosque’s file to Document Cloud so that their readers could read the original source of information throughout the article.

But how did these reporters pull this off? If someone published your work history online, wouldn’t you think that was an invasion of your privacy? It probably would be because most employee personnel files are confidential. Bosque, however, is a public official and an employee of a government agency, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, which is held to a standard of transparency and accountability to the general public.

The authors of this piece were able to obtain Bosque’s troubled past by filing a request for the Florida Department of Law Enforcement’s discipline cases under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). Analyzing and sharing these records allowed the reporters to call into question a system that was failing to fulfill its duty to serve and protect Floridians.

Moreover, their transparent research and reporting proved their credibility as journalists.

Journalists are “watchdogs over public affairs and government,” the Code of Ethics for the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) mandates. In this role, they are “to ensure that the public’s business is conducted in the open, and that public records are open to all.”

In our example, the Herald-Tribune forced the secrets of Florida Department of Law Enforcement into plain sight and kept it there so that the citizens of Florida would be informed of what was wrong with their local police department. As outlined in SPJ’s Code of Ethics, they had proven their credibility in uncovering and reporting information that was essential to the public making informed decisions about their government.

In this chapter, you will learn what public records are, and gain a general sense of which ones are readily available to you. For those records that are not freely accessible, we will discuss how FOIA can be a useful tool for you to access government information. By the end of this chapter, you will have a sense of how to access undisclosed public records using FOIA.

Public Records

As we did in the Public Records chapter, let’s reflect again on the documents that tell the story of you: birth certificate, school records, phone book, driver’s license, diploma, voter registration rolls, military records, discharge document, marriage certificate, mortgage lien, pilot license, diving certification, criminal record, inmate locator records, bankruptcy records, divorce decree, and, finally, a death certificate. If your life results in the production of all of these documents, then you’ll know you lived a very full life, indeed.

But who can access all of this stuff about you? That is, what information about you is public and what is private? Better yet, what information can you access?

There is an abundance of information that is available to everyone in the form of public records, which many journalists have used to craft compelling and credible journalism. For example, public records have been used by a teenager who blogs about the Supreme Court of the United States, or to create a database that people can use to police local homicide rates.

There are many branches and agencies that are required to publish their records. This means that the information you need may already be available through the Government Publishing Office (GPO). The GPO catalogues publicly available government information and links to the websites for other government branches for more focused searching and browsing. Most current government information is produced digitally, but this has not always been the case. As a result, you may have to work with a Federal Depository Library, such as the University of Kansas Libraries, which archives printed government information.

Your Right To Access

The right to access public records and demand a transparent government is deeply rooted in a strain of political philosophy used in the United States to justify the continuance of a free democratic society. This philosophy basically states that a democratic government is based on the will of the people, and the people need to know what the government is doing, in order to vote and make other informed decisions related to governance. The importance of an informed public having access to information has echoed throughout political theory:

“A popular government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy; or perhaps both,” wrote James Madison, a founder of the United States.

Only an informed electorate can govern effectively, to paraphrase the beliefs of Thomas Jefferson, founder and author of the Declaration of Independence.

“People denied information will make decisions that are “ill-considered” and “ill balanced,” reasoned political theorist Alexander Meiklejohn.

“A democracy without an informed public is a contradiction,” civil rights attorney Thomas Emerson, explained.

Their words recognize that citizens need transparent information to scrutinize the government. At the same time, just as transparency is important to maintaining a free democratic society, so are other things. For instance,

- Military effectiveness can hinge on the secrecy of tactics.

- Police officers hold information about investigatory tactics, which suspects may demand to know.

- The U.S. government holds information about citizens’ personal health conditions, but would infringe upon privacy laws if it released this.

In other words, how information feeds a democratic society is really about balancing interests. We may want to make particular information available, but don’t give short shrift to other public interests or private rights.

General Rules for Accessing Public Records

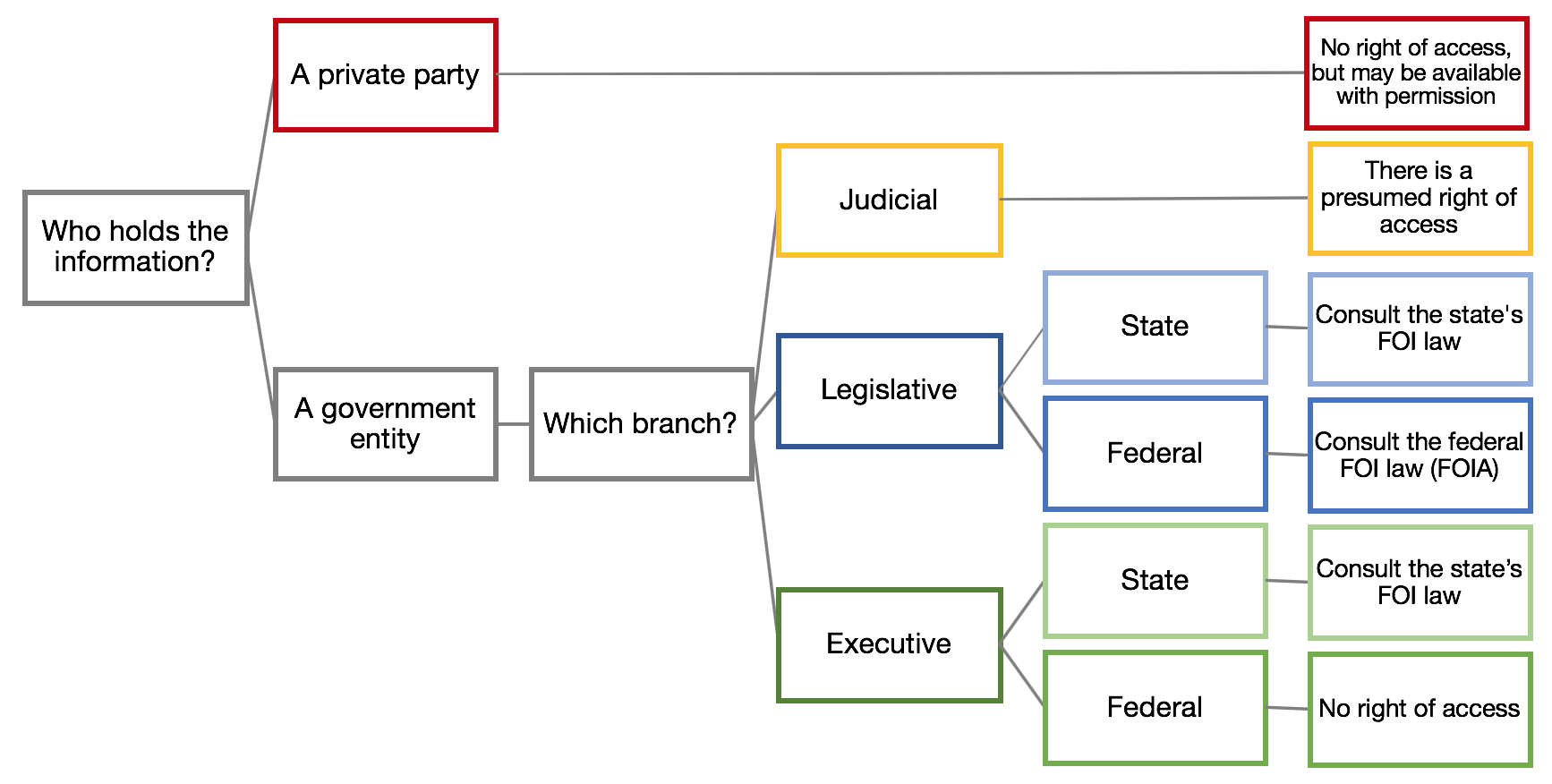

Let’s begin by looking at what information is publicly available and what is off limits for various reasons. For the purpose of determining whether you have a right of access, information can be divided into two categories: private and government. Government information can be subdivided into three categories, based on the branch that holds information: executive, legislative, judicial. Executive and legislative can be further split into two: federal and state.

For the purposes of our conversation, we are going to focus primarily on federal branches. Each state has its own laws of access, which lie outside the scope of this chapter (and the time you want to spend reading it).

This chart illustrates how these categories are divided:

Privately held information?

The easiest way to determine right of access to documents is to determine if the information is owned or held by private parties. If the answer to this question is “yes,” then journalists (or any person) can request access, but have no right to demand this access. You must obtain an owner’s permission to legally use privately held information. Using such information without permission will likely lead to people distrusting you and your work, and even legal action. Either way, your credibility will take a hit.

Accessing government information is not a clear-cut “yes” or “no.” There is a chance that the information you seek is already available. Below, I discuss accessing information from the judicial and executive branches of the federal government.

Judicial branch

Let’s first start with the judicial branch. Be aware that courts make records, and generally you’re entitled to look at them. For instance, state and federal courts often publish opinions, transcripts of oral arguments, case documents, and more. Accessing court information is generally governed by case law, and there is a First Amendment right of access to court proceedings and common law right of access to court documents. But in some cases, courts will permit restrictions on access (i.e., closing courtrooms, sealing documents, instituting gag orders). Those are done, typically, in the interest of justice, to ensure that parties get their fair shake in court.

So, do you have access to court documents? Yes, but it may not be to everything.

Federal executive branch

As mentioned above, many offices and agencies in the federal executive branch make certain documents readily available to the public. There are exceptions to this. Below, I will give you a rough outline of how to predict what will and will not be at the ready through the GPO or the like.

Freedom of Information Act

Congress created a right of access to federal executive branch records by enacting the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), which allows any person to request federal agency records for any purpose. This means that access to executive branch records is governed by statute. Let’s break down the elements of FOIA:

- Any person means any person. The requester doesn’t have to be US citizen, or a journalist, or fulfill any other requirements.

- Agency means all executive branch agencies (e.g., Federal Communications Commission, Federal Trade Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Internal Revenue Service, and the entire alphabet soup), the military, presidential commissions, the U.S. Post Office, and other government-controlled entities. However, FOIA does not include the president, the U.S. Congress, or the courts.

- Records means any paper or electronic record. This includes documents, computer files, databases, photographs, videos, audio recordings, and emails. It does not include physical objects. For instance, you can’t demand to inspect a person’s computer, look through file cabinets, obtain other objects. For example, a transcript of FBI interviews with witnesses about the assassination of President Kennedy would be a record, but the guns and bullets gathered as evidence would not be.

- Any purpose means any purpose. You don’t have to explain why you want the records, generally. But you may be required to state your purpose if asking for fee waiver. To get it, you must demonstrate that you’re making a request for the purpose of informing the public about government operations.

This means that many of these agencies, offices, and bodies will produce some information that is available to anyone through their website or GPO. All may have information that anyone may request. Not all information is available for consumption, however, because it may be classified for national security or for other reasons. There are no clear-cut lines with this, so you should work closely with a librarian or a professor who has experience with government information or FOIA before moving onto our next step, which is placing a FOIA request.

Before You Make a FOIA Request

Before you file a FOIA request, we recommend that you visit the FOIA website. Here, you will notice and click on a tab, “Before you request” before clicking “Search government websites.” Here, you can conduct a simple topical search for the information you are seeking. This will allow you to determine if the information is already available.

If you can’t find the information in your search or have questions, call the agency with which you will file the FOIA request. They can tell you over the phone if you will need to file a FOIA request.

Making a FOIA Request

After determining that you must file a FOIA request, then follow this advice and procedures.

You must request records in writing. Each agency has rules defining what must be included in the request and how the agency accepts requests (by mail, email, online submission, or otherwise). All agencies post procedures on their website and many provide the option of making requests online.

As an alternative, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press has created a FOIA generator and tracking system called iFOIA that allows you to fill out a form and generate a letter that can be emailed to the appropriate agency. It’s worthwhile to play around with iFOIA without submitting a request, to become familiar with the options and proper language for submitting FOIA requests.

FOIA request processing

Let’s break down this whole process. First, requests must reasonably describe the record you’re seeking. As a practical matter, it is important to describe records as specifically and narrowly as possible. Doing so makes it much easier — and faster — for an agency to understand exactly which documents are responsive and fulfill the request. Agencies are not obligated to fulfill requests that are so vague that they amount to fishing expeditions, or that require the agency to do research on the requester’s behalf.

This means that you need enough information before making a request to describe with specificity what you want. That a request may involve large number of documents is not a major issue. The question is whether the agency can reasonably figure out what those documents are without extensive independent research.

The statute regarding FOIA states agencies have 20 days to grant or deny a request, although as a practical matter, it may take longer. The law acknowledges times when an agency cannot promptly respond because it is flooded with requests and lacks the resources to respond in timely manner.

So, if an agency is otherwise acting diligently, courts will not punish an agency for being overwhelmed and understaffed. You might have to wait your turn, and that may take months or years.

Processing fees

You might have to pay fees for searching and copying costs. It is possible to get a waiver if you show that the records you want are of public importance.

But, if fees are not waived, you’ll be placed in a fee category, of which there are three: (1) commercial users, pay all costs, (2) noncommercial educational, scientific, or journalistic users, pay nothing for first 2 hours of research and first 100 pages of copies, and (3) all others, who pay for search and copy costs, but not review costs.

Journalists should include in their letter both a fee waiver request and a statement that if the waiver is not granted, they belong in the journalism fee category. If fees will be over a certain amount (typically $25), the agency will inform you so you can decide whether or how to proceed. But you should state the highest amount you’re willing to pay.

Exemptions

In theory, government should provide records responsive to a request unless one of nine exemptions applies. If an exemption applies, the government may withhold the requested information. There is a concept known as “discretionary disclosure,” which means an agency may choose to release records even if the request falls within exemption, but as a practical matter, you’ll rarely get anything covered by exemption.

Let’s discuss the nine types of exemptions.

- National Security: Congress granted the executive branch authority to determine which records should be withheld to preserve national security. For example, documents pertinent to ongoing armed conflict will likely be exempt.

- Agency Rules & Practices: This applies to records “related solely” to internal personnel rules and practices. Over time, courts divided this into two, called “high” and “low.” “Low” refers to records of mundane activities of no interest, such as where employees park. “High” refers to records vital to how an agency functions as an enforcer of the law.

- Statutory Exemptions: Applies to records declared confidential under other laws.Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) prohibits federally funded educational institutions from releasing educational records without consent, though there is some information universities can share, such as your email address. “Federally funded” means the institution receives federal funds, directly or indirectly. So, almost all schools are subject to FERPA.

Driver’s Privacy Protection Act (DPPA) prohibits release of personal information held in Department of Motor Vehicle (DMV) records without an individual’s consent. This does not restrict disclosure of information about accidents, driving violations, suspended licenses, and similar matters. It only restricts personal information such as address, Social Security number, height, and weight.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) prohibits health care providers from releasing protected information, such as medical records, without the consent of the patient. It applies to healthcare providers and business associates.

- Confidential Business Information: If record contents would qualify as a trade secret, they may be withheld. In other words, if someone could use the information to make a lot of money trading on Wall Street, then it’s a no.

- Agency Memoranda: Allows agencies to withhold “working documents,” like drafts of documents, internal notes, other preliminary materials that agency employees create or obtain in the course of doing their jobs. The reason? To allow employees to propose ideas or have honest discussions without fear that material will be disclosed and used against them. Everyone can make mistakes or propose ideas that need to be refined.

- Personnel, Medical and Other Personal files: Often called the “privacy exception,” it applies to information about a particular individual. When determining this exemption, the question is whether disclosure “would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.” The first issue is whether there’s information in the record that would raise a privacy issue. Second, a privacy interest must be weighed against the interest in disclosure.

- Law Enforcement Investigations: Government may withhold records compiled for law enforcement purposes if disclosure would (a) interfere with investigations, (b) deprive a defendant of a fair trial, (c) invade personal privacy, (d) disclose the identity of a confidential source, (e) reveal enforcement techniques, or (f) endanger life.As practical matter, broad language makes it difficult to get law enforcement records, at least until a matter is closed. Even then, portions of record may be redacted to hide names of sources or witnesses, or to prevent disclosure of enforcement techniques.

- Banking Reports: Applies to information related to examination, operating, or condition of reports prepared by an agency responsible for regulation or supervision of financial institutions. It is designed to promote openness between bank and examiners, and to protect financial institutions from the release of honest evaluations about stability.

- Information about Wells: Probably the least-used exemption, this covers “geological and geophysical information and data, including maps, concerning wells.” Congress intended to protect the oil and gas industry from unfair competition when it developed this exemption.

If the government ignores or denies a request

If an agency denies a request, in whole or in part, it should say why — e.g., because a request is invalid (fails to specify identifiable record) or because an exemption applies, in which case the agency should specify which exemption.

If you believe your request was improperly denied, you may appeal the agency’s decision. Each agency has different deadlines for filing an appeal. If you’re not satisfied after appealing, you can file a lawsuit, and the court will determine whether the agency acted properly.

Another resource is the Office of Government Information Services (OGIS), created by Congress to be a FOIA ombudsman. OGIS conducts mediation between requesters and agencies, smoothing communication and trying to improve the process of obtaining records.

As a last resort, you may consult with an attorney or your organization’s legal counsel and, perhaps, file a lawsuit in a federal trial court.

Lifecycle of a FOIA request

- Before you submit a request, determine if it’s necessary.

- Research which agency is likely to have responsive records.

- Request only what you want.

- Send the request to the appropriate agency.

- You’ll receive acknowledgement that includes a tracking number and the date the request was received, and whether the agency will comply within the 20-day deadline.

- You may be charged fees. An agency should provide an estimate.

- Agencies process the requests in order in which they are received.

- Once a search is performed, FOIA personnel review records to determine if exemptions apply.

- You will receive releasable records in one batch or portions distributed in rolling releases. If any portions are redacted or denied, an agency should cite the exemption(s).

- If you appeal and win, the agency will process your request. Timelines for their response will vary.

- If you are not happy, contact an agency to speak to their FOIA liaison, contact OGIS, or file a lawsuit.

Federal legislature

Although FOIA provides right of access to federal records, Congress exempted itself. No law or court decision gives citizens a FOIA-like right of access to Congressional records. If Congress refuses to hand out protected information, there is little recourse except to appeal to an official’s conscience — or political opponents, who may be willing to turn over information if they have it and it is not otherwise illegal to do so.

State laws

Every state has its own law for open records requests because they each have their own state agencies. Some state open records laws also cover their legislature, but other state laws don’t. Some require written requests, and others let a requester show up at an agency and ask to see records in person.

Each state is different. You must look at the law for the state where you want access. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press provides state-by-state compilation of laws, called the Open Government Guide, to guide reporters through their state laws and processes.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have defined public records and discussed some general rules for determining what information is public or off-limits to us. After touching on some tips for verifying that you will need to file a FOIA request, we discussed the lifecycle of a FOIA request.

Activity 1: Can FOIA help ya?

Search for a topic in which you are interested at the FOIA website, and identify what documents are publicly available. Explain how these might be useful to your research. Summarize and evaluate at least two sources.

Using the FOIA website, identify which agency you would need to contact to file a FOIA request.

Navigate to the iFOIA platform, create an account, and walk through the prompts to generate a FOIA request about the topic in which you’re interested, from the agency you identified on the FOIA website. Along the way, resolve any issues that arise (e.g., indicate whether you’re entitled to expedited processing and/or a fee waiver, and make your case accordingly). Decide if you will submit the request.

Activity 2: FCC Complaints

Using the iFOIA platform, draft a FOIA request for viewer complaints about violent television programming.

Assume that you’re a reporter for The New York Times, and you’re working on a story about consumer complaints sent to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) about violent television programming aired in the prime-time block from 2016 to 2017.

You want copies of any such complaints the FCC has received and copies of the agency’s responses to those complaints. You believe it is critical for the public to receive this information as soon as possible, because next week Congress will review the authority it has granted to the FCC to evaluate whether the FCC is performing its duties effectively.

With those things in mind, draft a request using the iFOIA platform. Create a free account, and follow the step-by-step prompts to draft the request. As you work, resolve any issues that arise (e.g., indicate whether you’re entitled to expedited processing and/or a fee waiver, and make your case accordingly).

Do not submit the request, since you’re not really a New York Times reporter doing a story on the FCC. But you can save it to your computer, or print it out.

Additional resources

- The iFOIA generator and project-management system.

- Muckrock helps you file, track, and share records requests.

- FOIA.gov: a government explainer and database on FOIA.

- State FOI resources from the National Freedom of Information Coalition (NFOIC).

- State FOI resources from the Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press.

- FOIA explainer and resources from George Washington University.

- Electronic Frontier Foundation’s (EFF) transparency project.

- FOIA Center from the Investigative Reporters & Editors (IRE).

- Society of Professional Journalists’ (SPJ) page for FOI-related info.

- SPJ’s page for state FOI-related info.

- The Student Press Law Center (SPLC) focuses on student journalists and access to school records.

- Federal mediation service for FOIA disputes.

Examples of FOIA-driven stories

- The Sunshine in Government Initiative maintains “Without FOIA,” a tumbler that tracks many news stories.

- Police disciplinary reports from the Miami Herald-Tribune.