10 Contend With Bias

Karna Younger and Callie Branstiter

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Distinguish between explicit and implicit bias.

- Define a number of bias categories.

- Identify bias in an information source.

- Discuss biases in search engine results.

- Include diverse perspectives when considering the credibility of information sources.

What Is Bias?

When evaluating the credibility of information, it is important to consider its bias. Bias is the “inclination or prejudice for or against one person or group, especially in a way considered to be unfair,” according to Oxford Living Dictionaries. Think back to our discussion in a previous chapter of Liz Robbins’ coverage of Serena Williams for The New York Times, and how bias factored into our evaluation. Though somewhat subtle, there were hints that Robbins seemed to favor and maternalize the white Kim Clijsters while alternatively infantilizing or portraying Williams as an “angry black woman.”

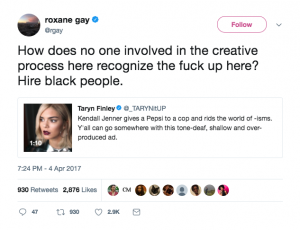

You may also remember that one time Pepsi partnered with Kendall Jenner to appropriate the Black Lives Matter movement to sell some soda. Audiences were quick to call foul, and Pepsi pulled the “tone deaf” ad. Roxane Gay, a bestselling author and associate professor of English at Purdue University, for one, called out Pepsi for its bias and not including black people in the creation of the video. She argued on Twitter that if creators had sought more perspectives beforehand, the commercial likely would not have made it to air.

In this chapter, we will define several categories of bias, and discuss how they may manifest in the information we evaluate or in information we produce.

Implicit and explicit bias

At the outset, it is important to acknowledge that all information is biased in some way. There are two primary types of bias: explicit and implicit. The Office of Diversity and Outreach at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) offers an easy way to distinguish between the two. Explicit bias is a conscious bias, meaning that we are aware of it. Implicit bias is a bias we are unconscious of, or that we don’t even realize we hold.

Implicit bias starts taking root during our early childhood, so that by the time we are in middle school we already hold prejudices against certain groups, even if this runs against our conscious morals or ethics. The good news, though, is that our implicit biases can change and are often more of a product of our environment than anything else, researchers find.

Implicit and explicit bias become problems because of the way our brain processes information. In the first chapter on evaluating sources, we discussed how psychologists say that we either process information quickly based on our prior knowledge, or that we are very deliberative and think critically about information. We rely upon our biases when we make quick decisions but can override such preconditions when we think deliberately and critically. There really isn’t a clear cut way to “teach” ourselves how to become better critical thinkers, cognitive psychologist Daniel T. Willingham says, but it is possible, and anyone can do it. Among his suggestions, Willingham has found that learning deeply about a subject, drawing from and challenging our life experiences, and developing critical thinking strategies to follow when evaluating information help us avoid cognitive biases.

In this chapter we identify some of the biases you may encounter while evaluating and creating information. There are over 170 identified cognitive biases, and we will cover only a small number of these. Learning about and improving our own biases is a lifelong process that cannot be summarized in a short chapter. In order to help you down this path, though, we will conclude our discussions of biases with some strategies communications professionals use in their work to overcome bias.

Peer Tutorial: Implicit vs. Explicit Bias

In this video, Julianna Cullen and Brittany Foster (JOUR 302, spring 2019) discuss examples of implicit and explicit bias.

Categories of Bias

Cognitive bias

Cognitive bias is an error in judgment as the result of our own implicit or explicit bias. Many biases stem from cognitive bias, and these biases have lasting effects on how we choose to consume information and news.

As information specialist Lane Wilkinson explains, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 loosened federal restrictions of media ownership. This legislation allowed mass communication companies, such as cable news companies, to compete with one another. The result was that for these companies, increasing shareholder value became much more important than maintaining their journalistic integrity. This, in turn, segmented the news media and the general public, with some people gravitating to some news outlets and completely avoiding others.

The filter bubble phenomenon, which we discuss more in a later chapter, has been fueled by this segmentation. Filter bubbles refer to our tendency to consume news and other information that support our preconceived notions, and to reject information that challenges these notions. Three categories of cognitive bias seem to sustain these filter bubbles:

- The Hostile Media Effect is one such cognitive bias with roots in mass communication theory. It is the tendency of those with strong opinions or beliefs to assume that the mass media is against them, in favor of the counter point of view.

- The Dunning Kruger Effect is another form of cognitive bias about overconfidence. It is the tendency of those with low ability or knowledge of a topic to overestimate their competency in that topic.

- Confirmation bias occurs when we only seek out and trust sources of information that confirm our own opinions. Have you ever chosen a topic for a research paper and sought out sources that only confirmed your thesis of that topic? That is an example of confirmation bias. Biases shape filter bubbles in which we consume information and, as you will read below, play into cultural biases as well.

Gender

In November 2017, NBC News anchor Savannah Guthrie announced live on the Today show that her co-host, Matt Lauer, had been terminated due to revelations of sexual misconduct. While he was officially terminated as the result of one specific incident involving an anonymous NBC News colleague, there was reason to believe that this was not an isolated incident, but rather an ongoing cycle of systemic sexual harassment involving Lauer at NBC News.

In light of his termination, USA Today published a video compilation of moments in which Lauer exhibited sexist or crude behavior during interviews of prominent celebrities and politicians, including a moderated discussion between Hillary Clinton and then-Presidential candidate Donald Trump. While Lauer grilled Clinton on her use of a private email server, he breezed through his conversation with Trump. It can be argued that, based on the totality of these instances, Lauer exhibited gender bias.

Race

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which has taken a programmatic response to defeating racism and other forms of discrimination globally, defines racism as follows:

“Racism is a theory of races hierarchy which argues that the superior race should be preserved and should dominate the others. Racism can also be an unfair attitude towards another ethnic group. Finally racism can also be defined as a violent hostility against a social group.”

UNESCO’s definition is incredibly broad for a reason. Racism can take many forms, and may be encountered through a number of overt racial macro-aggressions, such as the time people marched down Lawrence’s Massachusetts Street with versions of the Confederate battle flag, and more subtle micro-aggressions.

Such racial aggressions are able to occur because of white privilege. White privilege is “an invisible package of unearned assets which I can count on cashing in each day,” as Women’s Studies Scholar Peggy McIntosh defined it in her seminal essay, White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. In this piece, McIntosh delineates the ways in which whites are “carefully taught” not to recognize how they benefit daily from various forms of racism and the racial hierarchy. Her examples include being able to socialize with people in their own racial group and disassociate from people they’ve been “trained to mistrust and who have learned to mistrust my kind or me.” In other words, white people can choose to only associate with white people and get by just fine, whereas a group of non-white people might raise suspicions.

Ethnicity

Ethnic prejudice is a close sibling to racism, and the two and are often conflatable. Ethnic bigotry also occurs through similar acts of micro- and macro-aggressions.

Particular to the area of journalism, ethnic biases have come to the forefront when the media reports on Latinx communities and on the topic of immigration. For example, Cecilia Menjívar, a KU Foundation Distinguished Professor of Sociology, has found that negative media portrayals of Latinx immigrants often reinforce negative stereotypes of Latinx people, which leaves Latinx people striving to debunk such misperceptions in their daily lives. Joseph Erba, assistant professor of journalism at KU, likewise found that such stereotypes threatened the experience of Latinx college students, forcing them to combat the negative perceptions of their non-Latinx classmates throughout their time on campus.

Corporate bias

Corporate bias occurs when an information agency is biased toward the interests of its ownership or financial backing, such as an employer, client, or advertiser.

A recent example of corporate bias occurred at Newsweek. In early 2018, Buzzfeed broke the news that Newsweek Media Group (NMG), then publisher of Newsweek and International Business Times (IBT), had been buying web traffic to inflate its advertising rates and sales. In other words, NMG had committed ad fraud involving U.S. government ads.

One Manhattan District Attorney’s raid later, Newsweek reported that the magazine was under investigation, in part, because of it was sending millions of dollars to Olivet University, a Christian university founded by David Jang. NMG’s journalistic practices have been scrutinized in the past, but NMG management soon had just about enough of this negative press from its own publication.

A serious breach of journalistic ethics occurred while Newsweek investigated NMG’s advertising practices and its connections to Olivet University. NMG’s actions demonstrate how corporate bias can influence the production of a story. First, NMG management fired a reporter, and its executive editor and editor-in-chief. All played roles in reporting on NMG’s scandals. Next, NMG launched an internal review during which NMG management directly questioned sources, tried to strong-arm reporters into revealing their anonymous sources, and showed drafts of the article to subjects of the story.

The Society of Professional Journalists commands that journalists “resist internal and external pressure to influence coverage.” By revealing the article to subjects, NMG management directly applied such pressure to its editorial staff in hopes of altering content. In other words, the corporate entity tried to control the editorial content of Newsweek.

Rather than being bullied into submission, CNNMoney reported, Newsweek staffers continued working on the story outside of the office. NMG allowed them to publish the story only after they threatened to resign. The story ran under a disclaimer explaining Newsweek’s struggles to publish the article and a promise that the content of the story was free of corporate bias. The company’s owners promised Newsweek “newsroom autonomy going forward.” But, judging by its past, the future appears to be dubious for Newsweek.

In advertising and strategic communications, corporate bias is part of the nature of the work. Your clients essentially pays you to represent them in a positive light. But you have to walk an ethical line when doing so. Advertisers must remain mindful of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which enforces truth-in-advertising laws. PR practitioners must be guided by the Public Relations Society of America’s code of ethics.

In your role as a communicator, you act as a type of intermediary between the public and your client. Even though your client may pay you to promote them or their product, you must do so with the best interest of the public in mind. For instance, if you represent a celebrity who is paid to Instagram themselves with products, you will have to remind them to clearly state that it is a paid advertisement and not just a cute photo in order to adhere to the FTC’s advertising regulations.

Or, if you are developing a health-themed ad campaign for Rice Krispies cereal, you should make certain that scientists have verified that the cereal will boost a child’s immunity. When the FTC fined Kellogg’s for not backing up such a claim with scientific evidence, the cereal company had to pull all advertising that sported this claim.

It can be difficult to talk a client down from Instagramming their way to a new beach house or from promising that curing all ills is a snap, crackle, pop. But this is why communicators must establish good agency-client relationships that value transparency (so they will tell you the truth) and clear and collaborative communications (so that they can tell you the truth).

Algorithms: Human-inspired bias

In her book Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism, Safiya Umoja Noble details the biases inherent in Google searches. Much of her research stems from a 2010 incident in which the top results of a Google search of “black girls” yielded explicit pornographic content. Noble argues that these primary representations of black women in Google searches are representative of a “corporate logic of either willful neglect or a profit imperative that makes money from racism and sexism.” You can watch this video to learn more about Noble’s work.

In his book, The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is hiding from You, internet activist Eli Pariser predicted that personalization and Google News would forever change the media’s role in democratic societies. He summarizes his argument in the following TED Talk video:

Historically, Pariser argues, the media has acted as the informed mediator between politicians and voters, who typically read one preferred newspaper to inform their decisions. Now, though, people can access a variety of sources indirectly through Google News. Google News, like all Google products, is designed to create a personalized experience and provide people with information that they prefer to read.

The problem with this, Pariser warns, is overpersonalization, which can exclude important news from a person’s feed completely because it does not fit with someone’s reading profile, or it just isn’t really popular. In other words, depending on your preferences and reading history, you may not know if our country goes to war, but you’ll be totally up on who won this year’s Puppy Bowl.

Bias in Journalism

Let us not despair that all is lost to bias. By being aware of our own biases, we can mindfully work to produce more balanced and inclusive work. According to Harvard’s Project Implicit, “If we want to treat people in a way that reflects our values, then it is critical to be mindful of hidden biases that may influence our actions.”

Taking an implicit bias test, reflecting upon its results, and intentionally countering our own biases is one important step we may wish to take. Below, we share how some professional journalists have worked to counter their own biases to benefit their work.

One Atlantic Monthly reporter was shocked to realize that he only quoted women 23 percent of the time across 24 articles, and that 35 percent of the time he didn’t include any female voices in his writing at all. Ed Yong frequently covers the field of science, which has its own gender problems, and never thought that he would be part of the problem that marginalizes and devalues women and their scientific contributions.

But gender bias in journalism isn’t just a guy thing. In fact, Yong reflected upon his work after reading that a female colleague, Adrienne LaFrance, suffered the same fault. LaFrance got help from a computer scientist for some serious number crunching of her own writing. This analysis made her realize that she didn’t even consult women for 60 percent of her work, and often gave men more space in her stories when women were included. Ouch.

Issues of race are equally problematic. In one study we conducted, we found that undergraduate students often use familiar, white-authored resources when producing their own work. For instance, students overwhelmingly consulted The New York Times as a primary source in their research, even when they were in classes that focused on non-white historical perspectives, or counternarratives.

Now, The New York Times isn’t a bad primary source to use. It has been one of the nation’s leading newspapers since it was founded in 1851. But for most of its history, white men have helmed the paper and produced its contents. Moreover, during our discussion of one New York Times reporter’s coverage of Serena Williams in one of the credibility evaluation chapters, we likely saw hints of white privilege.

Some Ways Forward

We can’t pretend to have a simple fix for these deeply problematic and complicated issues. We will provide you with some examples of how professional journalists have fought to decrease bias in their own work.

First, LaFrance and Yong pledged to be more intentional. For the most part, Yong has continued to do what he has always done, but spends about 15 more minutes searching for sources until he has a list of female contacts. Additionally, he is tracking who he contacts and interviews for stories. As a result of his mindfulness, Yong is now citing women about 50 percent of the time. This also has catalyzed him to start tracking how many times he includes voices of color, LGBTQ folks, immigrants, and the disabled.

LaFrance, meanwhile, realized that she needed to change up her list of go-to sources and consider seeking out stories that focus on the achievements of women. It works for Yong and LaFrance, so it will probably work for you, too.

Once you have identified a diverse pool of sources, it is important to conduct inclusive reporting. Writing about the developing journalism ethics of covering transgender people, reporter Christine Grimaldi outlines some important tips. She suggests asking people their preferred pronouns (she, him, they, xe, or ze), and then using such preferred pronouns in your work. She cautions against asking everyone anything, citing the need to respect a person’s right to privacy. When the AP Stylebook fails you, turn to the stylebook for the National Association of LGBTQ Journalists or the GLADD Media Reference Guide. Finally, don’t be afraid to ask your editor, manager, or experts inside and outside of your workplace for guidance.

Recognize that there are many experts and professional organizations you also can turn to for guidance. For instance, the National Association of Black Journalists also has its own style guide, and the National Association of Hispanic Journalists offers points of guidance. These are just a few examples.

We want to reinforce that everyone is biased in some way or another. But there are ways to use this bias for the greater good. It simply means that you have to remain aware of how your bias may affect your work. Ronan Farrow exemplifies how a journalist may do so. Farrow is son of Hollywood actress Mia Farrow and director Woody Allen, a former Hollywood It couple. In 2017, he published a story in the New Yorker recounting explicit details of alleged rape and abuse by disgraced Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein.

While Farrow’s piece was not the only one or the first one, it caught a lot of people’s attention because of Farrow’s family history and his possible bias. Farrow has long been a staunch advocate for victims of sexual abuse since he first vocally supported his sister, Dylan Farrow. As a child, Dylan Farrow accused their father, Woody Allen, of sexually molesting her, and, as an adult, has called out the Hollywood elite for continuing to support Allen’s career. Though Allen was never prosecuted, the allegations of sexual misconduct and inappropriate relationships have caused some to question if Allen’s time is up.

What is important to note is that Farrow was mindful of his possible bias throughout his reporting. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter (THR), Farrow said: “Probably, yes, the family background made me someone who understood the abuse of power from an early age.” Even Weinstein himself tried to stop the story by alleging a conflict of interest, Farrow disclosed. Though Farrow believes his life experience helped him relate to survivors of sexual abuse with empathy, he denies that his life experience biased his reporting. Farrow told THR: “My mandate going into the Weinstein story was never to believe all survivors; it was to listen to all survivors. I think it’s completely possible to be both a skeptical, judicious reporter and also create a space for survivors to be heard.”

Creating a space for others to be heard is a good place to end this chapter and to begin your own research. Remembering to respect everyone’s voice and to not overpower it with your own can be difficult. By being mindful of your own biases, you can make a brave attempt to focus and listen.

Grammar and Spelling Review

Finally, let’s make sure that we are all on the same page about how to spell and when to use variations of the word “bias.”

- Bias. This is a noun, signifying a singular bias. Correct ways to use this word:

He or she has a bias toward something.

They have a bias against something.

There is bias in this piece of writing.

- Biased. This is an adjective, which means that it describes something, like a person or another information source. Correct ways to use this word:

He or she is biased.

They are biased.

The piece of writing is a biased report.

- Biased. This also can be a verb, in the past tense. Correct ways to use this word:

This experience biased me.

This information biased them against something.

- Biases. This is a noun signifying more than one bias. Correct ways to use this word:

He or she has several biases.

There are biases in this piece of writing.

- Biases. This also can be a verb. Correct way to use this word:

This experience biases the people who go through it.

A Practitioner’s View

Scott Collin

B.S., KU Journalism, 1994

Executive Creative Director, Havit Advertising

One might assume that you develop –- if not need –- bias to be a smart advertiser. Especially when it comes to conducting and evaluating research. Why? In advertising, your job is to get potential customers to love products and services. So … you need to be the ultimate brand advocate, right?

Well, not always.

Business isn’t about what you’re selling. It’s about what the consumer is buying. So you have to remind yourself constantly that facts are facts. And whatever it is you feel or assume about information needs to be placed carefully to the side, possibly across the room.

You have to remove your own emotions and take on those of someone who is not sitting at home waiting for your commercial to run, or print ad to delight them as they turn the page.

Prospects don’t know your product, and possibly not even the brand. And just like you can’t walk into a party and tell someone you’re ‘cool’ … you can’t just tell someone they need to buy something because you think it’s great.

I created campaigns for infant formulas long before I was a dad, and for Formula 1 racing while driving a 14-year-old Jeep. And the way I did it was to fully understand the target audience and its bias (for or against) a product, and then went from there.

Activity 1: Ad Bias

Evaluate the credibility of a news article or an ad campaign of your choosing. Identify the primary form of bias in the piece, and provide suggestions for minimizing its bias. Use evidence from the evaluated piece and other sources to support your argument.

Activity 2: Search Bias

- Watch Safiya Noble’s critique of Google’s algorithm. In her talk, Noble is critical of how Google’s search results portray women of color.

- Google a topic that you know is politically polarizing, or that you have seen portrayed in a biased manner in the media.

- In a two-minute video, discuss what biases you notice in your search results, if any. If possible, compare your search results with those from someone else’s computer.

Activity 3: Implicit Bias

Take Harvard University’s Implicit Bias Test. Your results of this test are private and you are under no obligation to share them with anyone. Without divulging details, reflect in one paragraph on the difficulties in addressing implicit bias in a professional setting.

Activity 4: Diverse Voices

Read Christina Selby’s tips on including diverse voices in stories. Although Selby focuses on the sciences, much of her advice is useful for other areas of journalism and advertising. In 1-2 pages, reflect on how you can incorporate some of Selby’s ideas into your own work.