3 Search More Effectively

Peter Bobkowski

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify search operators for use in Google.

- Use search operators to conduct effective and efficient searches.

- Use Google’s reverse image search.

Search Operators

As we set off on our research process, let’s cover some strategies that can make our information searching more efficient.

We all have had the experience of typing some search phrase into Google and being overwhelmed by the millions of search results that come up. The following strategies, also known as operators, can streamline our searching so that we waste less time sifting through links and sources that don’t address our topics.

These operators all work in Google, and some also work in specialized databases that you access through a library or another website.

Use quotation marks

Watch this video on phrase searching.

The key takeaway from this video is that multi-word search terms enclosed by quotation marks return more specific results than the same search terms without quotation marks.

For instance, the search phrase

unicorns in Kansas

returns approximately 1,420,000 Google results as of the date of publication that contain the words unicorns, or Kansas, or both (but not necessarily both).

The search phrase

“unicorns in Kansas”

returns seven Google results as of the date of publication, both of which contain the exact phrase “unicorns in Kansas.”

An additional important point made in the video is that it may be worthwhile to use different versions of a phrase when using quotation marks. For example, the search term

unicorn in Kansas

returns 8,360,000 search results as of the date of publication. Apparently writing about one unicorn is more popular than writing about a unicorn herd.

Remember that using this operator only makes sense for two or more words. Putting quotation marks around one word will not alter the search results

Use AND and/or OR

Watch this KU video on combining search terms.

These operators are useful for exploring the search results of combining two or more search terms. To see how the results differ after using these operators, open two browser tabs to Google and type two unrelated words in the search bar. In one, place AND between the two words, and in the other, place OR. Click between the two windows and explain the differences in the order of the search results.

Use the minus sign

Sometimes when we search for a topic that’s similar to a very popular search topic, it’s hard to find the search result in which we are interested because of the overwhelming popularity of the other topic that’s not-quite our topic. Inserting a minus sign in the search string, followed by the search term we don’t want to see, will eliminate results with that search term from our results list.

For example, let’s say that we are interested in researching the sources of whale mortality, and we want to use the colloquial search phrase “whale killer.” If we type

whale killer

with or without quotations, Google will return for us a ton of results on killer whales.

But if we use the search string

“whale killer” -“killer whale”

we will get results that contain the exact phrase “whale killer,” and no results about killer whales.

We can use the minus sign as many times as we want in one search string. For example, if we want to scrub our results of all possible mentions of killer whales and anything else that may be related to them, we might use the search term

“whale killer” -“killer whale” -orca -blackfish

because orca is another term for the killer whale, and Blackfish is a popular 2013 documentary about these whales.

Note that there is no space between the minus sign and the word of phrase you want to leave out. Adding the space confuses Google.

In the Libraries’ subscription and other databases, instead of using the minus sign you can perform the same feat by using the operator NOT.

Specify the domain or website

A top-level domain is a group of websites whose URLs end in the same letters. We know them as .edu, .gov, .org, and .com websites. Top-level domains also can designate a website’s home country, like .ca for Canada, .mx for Mexico, and .dj for Djibouti. (Here is a list of all the possible top-level domain endings, most of which we never see used.)

Can you think of research topics that would make it useful to narrow down our search results to a specific top-level domain?

We may be looking for official government sources on a specific topic. If so, we would type our search term, followed by site:gov.

For example, our search string might look like this:

“killer whale” site:gov

Or we may want to look only for nonprofit sources on a topic. Our search string might look like this:

“killer whale” site:org

We can further narrow down a search to a more specific domain or website. For instance, if we want to find experts at the University of Kansas who specialize in killer whales, we might use this search term:

“killer whale” site:ku.edu

because ku.edu is the top level domain for all web pages at the University of Kansas.

Or, if we want to read an article published by a specific publication, we can narrow down our search to that publication’s website.

Let’s say that we want to search the website of the Lawrence, Kansas, newspaper, the Lawrence Journal-World, for the address 803 Massachusetts. This is where the popular The Burger Stand restaurant is located, and we want to learn what other businesses operated in this building before The Burger Stand. To do this, we might use the search term:

“803 Massachusetts” site:ljworld.com

for articles published on this newspaper’s website.

Note that there are no spaces between the word “site,” the colon, and the domain name or extension. Spaces make operators inoperable.

Specify the document type

The names of computer documents have specific filetype endings, like .doc or .docx for Word documents, .ppt or .pptx for PowerPoint presentations, and .pdf for PDFs (which stands for “portable document format,” by the way). You might guess where this is going: we can narrow down our searches to a specific filetype.

Can you think of research topics that would make it useful to narrow down our search results to a filetype?

Official documents, research reports, and forms often are saved as PDFs. Specifying

filetype:pdf

after our search term will turn up only PDF files in our search results.

Teaching and professional presentations, meanwhile, are often saved as PowerPoint documents. Specifying

filetype:ppt

will result only in those files showing up in our search results.

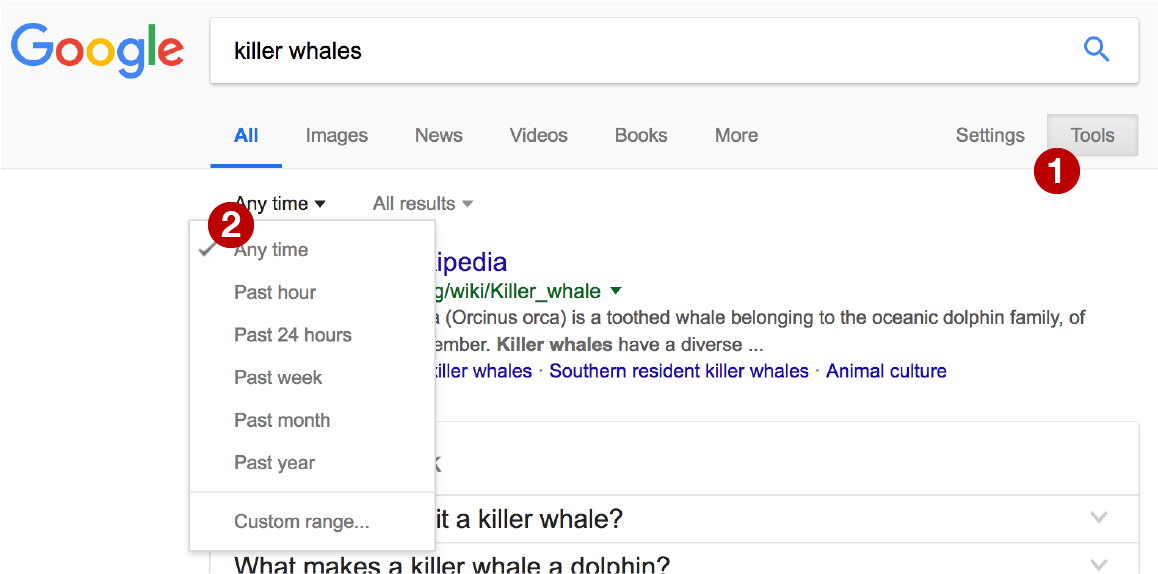

Specify a date range

Sometimes we may want to access the most recent information on a topic, while at other times, we may be searching for the oldest information out there. Most search engines and databases provide the option of organizing results by date. Some databases organize results from newest to oldest by default, while in other databases, we have to specify our preference for this ordering or another. It is usually also possible to designate a date range for our results.

To specify the date range in Google, after typing a search term and getting initial results, click “Tools” below the search bar, and use the drop-down menu next to the “Any time” tab.

Combine the operators

We can make our search strings as elaborate as we need them to be, so feel free to combine any number of these operators in the searches you perform.

In Google, you can also access an Advanced Search form in which you can specify a number of these and other operators without using the shortcuts we discussed here.

Reverse image search

This last Google search trick we discuss in this chapter may not be useful when researching a regular topic, but it may be handy when verifying the authenticity of a photo. It also is used by people who suspect that images belonging to them are being posted around the Internet without their permission.

Here’s a short video about reverse image searching.

Peer Tutorials: Search Operators and Image Tools

In the following video, Kylee Xu (JOUR 302, fall 2018) reviews three search operators: Quotes, the minus sign, and specifying a domain name.

In the next video, Angelica Lance (JOUR 302, spring 2019) discusses tools for examining the sources of digital images.

A Practitioner’s View

Kayla Schartz

B.S., KU Journalism, 2016

News Producer, KMBC-TV, Kansas City, Mo.

As a TV news producer, I work under tight deadlines every day. Part of my responsibility is to make sure I have the most up-to-date and accurate information in my newscasts. To deliver on that, I have to fact-check my content.

I often rely on Google searches for fact-checking, but I don’t have time to sort through the millions of search results. That’s why I use search operators to make my job a little easier.

For example, during the election season, I have to fact-check claims made by candidates, on issues or voting records. I often combine the use of quotation marks as well as AND to search a candidate’s name and the claim I’m looking to verify to cut down on the number of results.

The reverse image search also has been a good tool for me when it comes to making sure weather photos are authentic. Pictures from past weather events often start recirculating on social media during storms, so a reverse image search is a good way to make sure a photo is from the storm I’m looking to cover on any given day.

Activity 1: Search Term Practice

Practice combining different search operators by coming up with increasingly complex search terms.

Activity 2: Open Pedagogy

In a video or a slideshow of screenshots, illustrate how a Google search using one of the search operators discussed in this chapter is more efficient than the conventional way of conducting a Google search.