9 Tap Into a Credibility Network

Karna Younger

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Use four fact-checking moves to research the credibility of information.

- Identify critical questions to ask about the content of an information source.

- Use context culled from other sources to contextualize the credibility of an information source.

Going Deeper With the Tabs

In the previous chapter we walked through identifying and evaluating credibility cues. We pinpointed these cues (e.g., publisher, article title, date, etc.), and started opening lots of tabs in our browsers to research the different elements. We pinpointed these cues, and started opening lots of tabs in our browsers to research the different elements. If you followed along, your browser probably looked something like this:

Looking at all those tabs is exhausting. But it’s also what successful fact-checking looks like, so let’s get used to it.

In the Stanford study we mentioned at the beginning of the previous chapter, the fact-checkers were more adept at evaluating the credibility of information than historians and Stanford undergrads. In addition to opening up a series of tabs, the fact-checkers read, evaluated, and judged information against the greater network of information they accessed. This does not mean that they simply went with what the majority of other websites or people had to say about a topic. They used the network to reason a source’s credibility.

In this chapter, we focus on four moves that the fact-checkers in the Stanford study repeatedly made. Our goal is to practice the cue-evidence method some more, while also drilling down on some concepts that we didn’t cover fully in the last chapter. The following list of these moves is adapted from the textbook Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers by Mike Caulfield. Using these moves can help us dial into the greater network of knowledge and make an informed credibility call about an information source we are evaluating.

Check for previous work

Look around to see if someone else has already fact-checked the claim or provided a synthesis of research. Checking for previous work allows you to weigh what you are reading against other accounts, and determine what is fact and opinion. If you are researching an event that occurred in the past, you may also look at things that have been published since the event occurred. Also, “work” is not restricted to any information type or genre. You may look at primary or secondary sources or news articles, dictionary or encyclopedia entries, or scholarly information. This process and those below involve opening a lot of tabs to research our work.

Go upstream to the source of the claim

This is another way of saying that we should rabbit hole, as we did in the chapter on primary and secondary sources. Going upstream to the source means that we need to find some primary source(s) that relates to an author’s claim. This could mean finding a video of an event or an interview with someone who was directly involved. Comparing what a primary source says against what our original source (typically a secondary source) argues will help us better understand how the author of the secondary source is interpreting events or what bias the person holds.

Read laterally

You already know this move: Start opening those new tabs. Reading laterally also should push us to further question what possible interpretations and biases are put forth by our original source and any primary sources we have found.

Circle back

Circling back helps us get our bearings in this maze of tabs. It reminds us to return to the source we were originally assessing to evaluate different components. Think of this as the repeat button. You can walk through this entire process for each credibility cue, for instance, and circle back to the original source after successfully evaluating each cue.

This is not necessarily an ordered process. And, as you can tell from your above experience, you will likely have to do this repeatedly. Not only for the cues in your original article, but also for cues you find in the resources you are using to fact-check your original source. This could get messy, which is why it is good to take good notes along the way.

Keep in mind, there can be some overlap between these steps. For instance, if you are evaluating an older claim or source, checking for previous work and reading laterally may yield some of the same results. This is fine. But you should gather some history on the topic (previous work) and more current things (reading laterally).

First cues: Publisher and author

Let’s walk through this process together with an article on Serena Williams published by The New York Times.

Before we even begin reading the article, we ask ourselves if we trust the sources of information, newspaper and the author. The New York Times is one of the nation’s largest newspapers and has been in business for a while. But we shouldn’t just rely upon our knowledge but should go upstream to find some primary source material about the publication. If we scroll to the footer of websites, we will often find information about the company. If we do that now, we can click on The New York Times Company link to find out more about the Times through its parent company.

This next page takes us down a rabbit hole. At a quick glance, we can see the paper has been in business for over 100 years and has garnered some Pulitzer Prizes, journalism’s top prize for reporting. We can look at the leadership, but instead focus on standards and ethics to learn more about their credibility standards.

Here we can see that the publication claims to adhere to fairness, integrity, and truth. Below this are explicit and lengthy explanations of their Guidelines of Integrity, which include their fact-checking process, and a Ethical Journalism Guidebook, or their code of conduct for staff members. We could cite these sources in our evaluation of the Times. For instance, we could say that we believe the Times is a credible source because it is transparent about listing its staff and policies, and that its policies carefully delineate the paper’s fact-checking processes and standards of ethics, which stipulate an adherence to reporting the truth.

We could also search laterally to see if other publications ever quote the Times. This search yields a Wikipedia entry and numerous stories quoting Times reporting and analyzing their business strategies, so we know that the Times is a well-known source of information that is critically evaluated and relied upon by its peers.

Next, we turn to the author. Liz Robbins was a sports reporter for the Times back in 2009 when she wrote about Serena Williams’s loss to Kim Clijsters at the United States Open. The first thing we could do is search laterally and go upstream by clicking on her hyperlinked name to scroll through her other writings at the Times. This tells us that she has most recently been reporting on immigration. This is not too similar to the topic of professional tennis, so we might ask why she is the reporter in this situation.

Continuing to search laterally, we plug her name and “New York Times” into a search, to see what other sources say about her. This would yield her Twitter page. Here we read that she currently covers immigration for the Times’s metro section, but that she used to be a sports reporter, is a cyclist, and published a book about some race. If we search for her book title and her name, we find a listing on Amazon that tells us the book is about the New York City Marathon.

Based on all of this information, we might tell ourselves that Robbins seems to have some experience reporting on sports for one of the top newspapers in the nation, is an athlete herself, and has even published a book on a major sporting event, but that we are not certain about her authority as an expert in tennis.

Then we can start reading the actual article.

Next Cue: Content

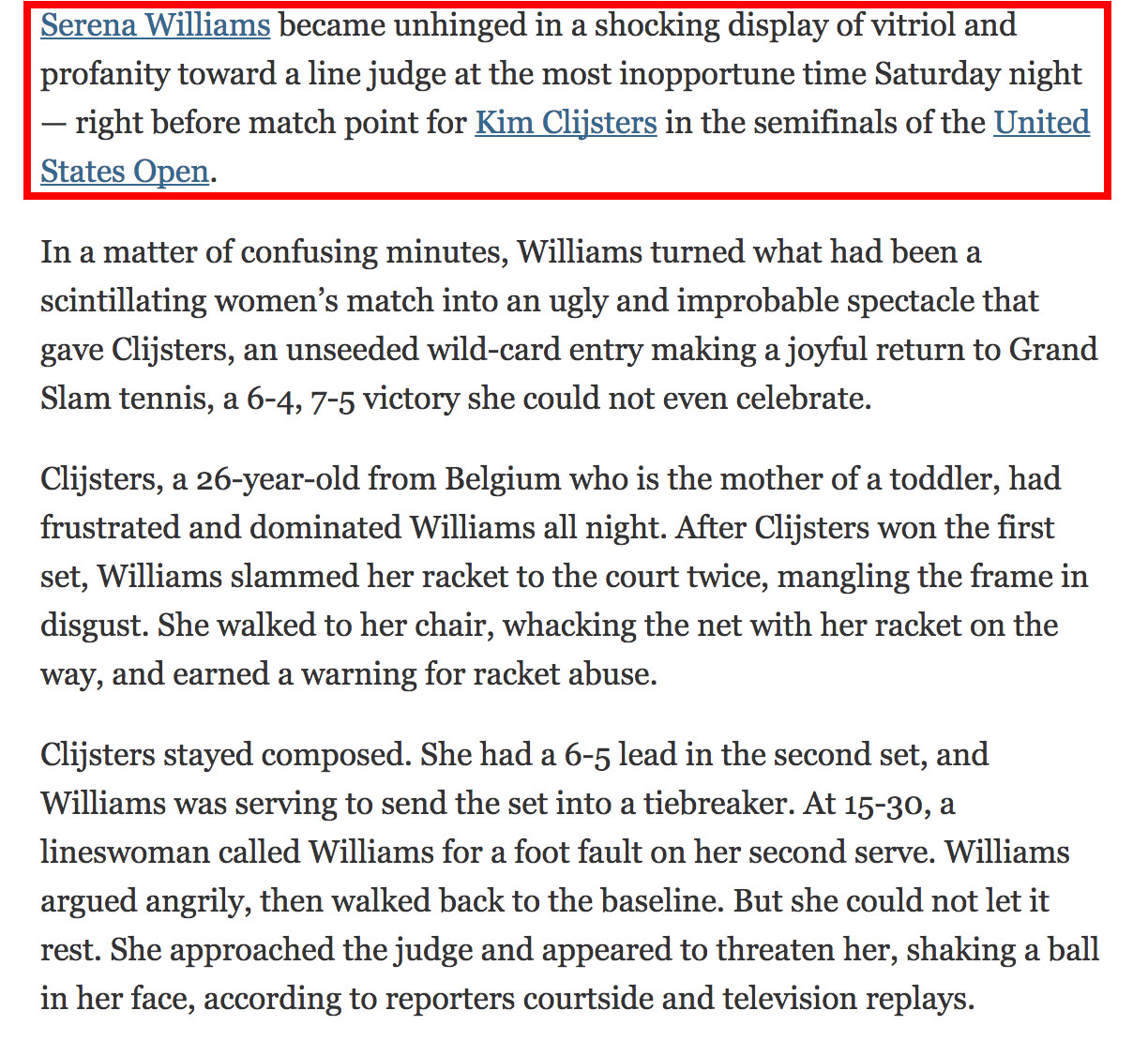

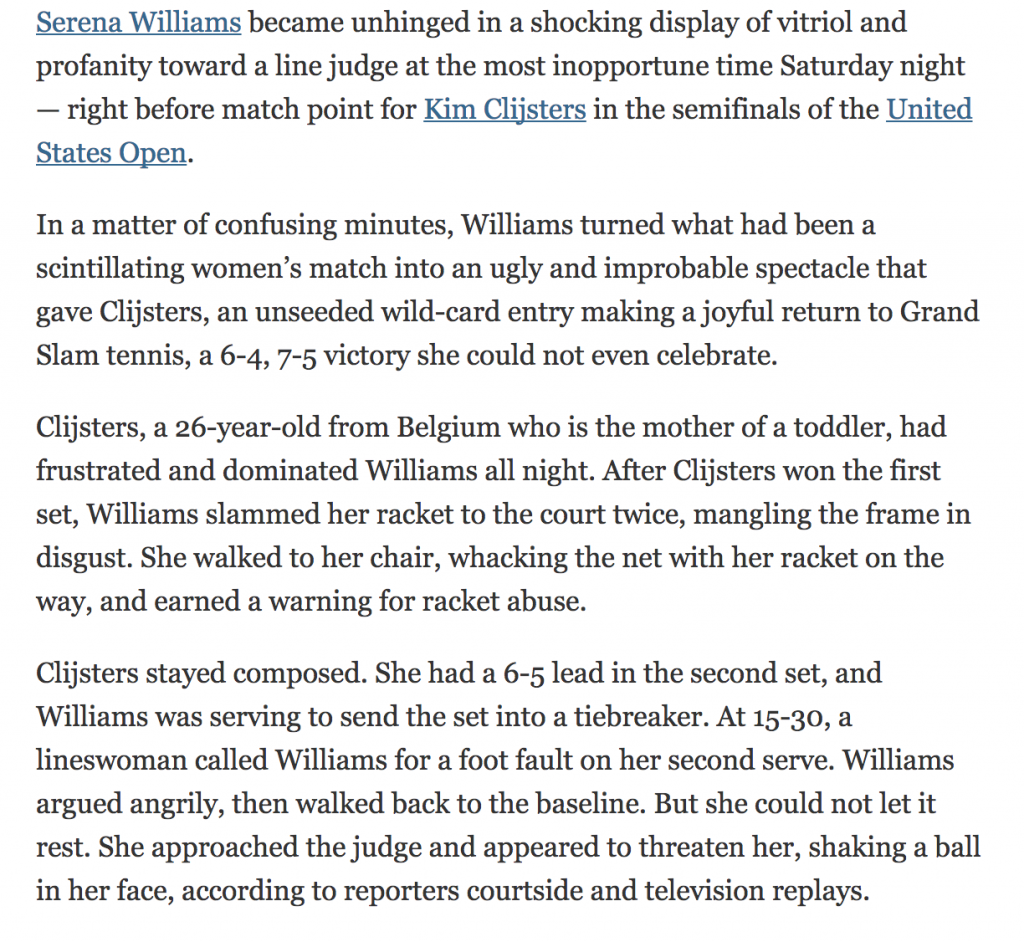

The article focuses on how Williams was forced to forfeit a match in the 2009 US Open after being assessed a point penalty for unsportsmanlike conduct. Williams garnered the penalty after she disagreed with a line judge’s foot-fault call. Below you can read the reporter’s summary of events in her lede, that is, in the first paragraph of the article.

Reading over the lede and maybe skimming over the subsequent paragraphs, we can start to figure out the substance of the article. We know that Williams and Clijsters faced off in the semifinals, and that Williams lost her temper just when she was serving to break the tie. Robbins plays up how differently Williams and Clijsters acted from one another, positioning Clijsters as “composed” and Williams as a vitrolic. It isn’t until the fourth paragraph that Robbins reveals what got under Williams’s skin.

We discover that the upsetting incident occurred during the second set of the game while Williams was serving. At this point, a line judge foot faulted Williams, which caused Williams to approach the line judge and shake a ball in the judge’s face. Robbins cites courtside reporters and television replays as her sources. The author could be citing other sources here because she may not have been in a position to directly see or hear what Williams might have said to the line judge.

Possible questions to answer

At this point, we have been reading and skimming for several seconds. While we are trying to understand the substance of the article, we probably have many questions that we can jot down. In parenthesis, we can note which of the four steps may help us answer our questions. Between each question, we will circle back.

- What is a foot fault and was it the correct call? (Check for previous work to fact check the author’s claim that Williams’ faulted before her reaction to the judge.)

- Why did Williams react like this? What really happened? (Go upstream to an original source to judge the author’s style and sources)

- Was Williams’s reaction really “shocking?” (Read laterally to determine if the article’s substance and sources are supported by other resources)

This list is not exhaustive. Additionally, you could easily and correctly argue that different or all four of Caulfield’s steps could answer our questions. These are just a few ideas to work through these steps together.

What is a foot fault?

First, let’s check for previous work to see what a foot fault is and if someone else fact-checked the claim that Williams faulted. Maybe another author could verify what Williams said to the line judge. We open the next tab and Google “foot fault” in quotes. We might also add the term tennis to this.

Some of our top results are dictionary definitions, which can be useful. But then we spot a National Public Radio (NPR) interview with a former line umpire that was published at the same time as the Times article. We can listen to the audio or read the transcript of the radio interview.

This source tells us that a foot fault is when a player touches the baseline, or line at the back of the court, while serving the ball in tennis. However, the former umpire equivocates on whether or not Williams did commit a foot fault.

The umpire states that he has only seen footage of the match, and that he could not tell from the angle whether Williams touched the line. He does seem to support the line judge who made the call, explaining that she “absolutely” would have known if Williams committed a foot fault from her vantage point.

As we mapped out in the previous two chapters, we could then go down the rabbit hole, researching the NPR interview’s primary sources. For instance, we could research the reliability of NPR as a source, the background of the NPR reporter, or the former line judge’s career to verify his credibility as a source. We will not go down these rabbit holes for the sake of time and, instead, we will circle back to our larger question of whether or not Williams committed a foot fault, knowing what a foot fault is, but still questioning what actually happened.

Was it the correct call?

Back with the Times article, we can take a closer look at what sources Robbins cites when describing what happened. Robbins is pulling this information from “reporters courtside and television replays.”

Later in the article, Robbins gets a bit more specific. She refers to audio from CBS’s broadcast of the match and The Miami Herald.

The author has given us two sources. First, the broadcast of the match would be a primary source that might yield more results. We know that the video might not give us exactly what we want. Robbins was able to listen to Williams on the CBS broadcast, but the umpire interviewed by NPR couldn’t quite see if the call was fair. We should search for similar coverage to evaluate the happening ourselves. Additionally, The Miami Herald and other “courtside reporters” covered the event, so we can be certain to find other accounts to play off Robbins’ account and our own interpretation of the video.

To get our bearings on the situation, we will swim upstream to the source. In this particular case, it is to a video of the match brought to us by YouTube. Keep in mind, YouTube often has several different versions of a video, so you should take time to consider all of the possibilities. This version was the one that provides us with a decent view of Williams’ serve and some snippets of the courtside conversation.

https://youtu.be/GTc-gv8tNWQ?t=13m50s

After reviewing the video, we could make some judgement calls. First, we might be willing to say whether or not we agree with the line judge’s call. The umpire interviewed by NPR said he couldn’t tell from the video he watched. Can you tell from this video if Williams faulted?

Additionally, we can notice other elements of the scene. We can witness Williams’ interaction with the line judge and other tennis officials, deliberating whether she became “unhinged in a shocking display of vitriol and profanity,” as Robbins described. Would you describe Williams’ behavior with these words? Can you hear what she said to the line judge? What about her verbal exchange with other tennis officials. What does this interaction tell you? What about Williams’ exchange with Clijsters?

We also can notice the behavior of the crowd, the Williams family, camera-toting courtside press, and other tennis officials. Do they act shocked? As a primary source, the video provides us with greater context to judge the credibility of our Times article. It places us in the shoes of Robbins, and pushes us to understand and interpret what happened.

What do other sources say?

Now that we have witnessed the event as best as we could without actually being at the match, let’s get some other reportings by reading laterally. We will focus on some of the claims and content of the article, and compare it to primary and secondary sources. This will enable us to weigh our own interpretation of events against the viewpoints of the Times’ Robbins and even the umpire interviewed by NPR.

We can read the different opinions and interpretations to see what other evidence is out there and, based on the evidence, which argument we most agree with. Ultimately, even though these additional sources may not directly address the Times article, they will help us evaluate the Times article by reinforcing or contradicting Robbins’s argument or by introducing new information.

A quick Google search yields an article from The Christian Science Monitor that promises to introduce new information. Robbins was not certain of what Williams said to the the line judge. The Monitor provides the missing evidence of what Williams actually said. (If you are unfamiliar with the Monitor, you could skim the about section to learn more about its editorial policies and history to research its credibility or search for what other reputable publications have to say about its bias.)

Mark Sappenfield’s account does not contradict Robbins’s reporting. He does offer more detailed first-hand accounts of the what happened though, including what Williams said to the judge.

By citing other reporters who were at the scene, Sappenfield followed the same reporting techniques and sourcing that Robbins did for the Times. Unlike Robbins, Sappenfield named his sources, making it easier for readers to fact-check and judge the credibility of Sappenfield’s account.

For instance, we can deduce that Sappenfield’s quotation from a CBS outlet could be reliable because, as we know from Robbins’s account and our video searches, CBS broadcast the match. Sappenfield even tells us how close one of his sources was to the court, enabling us to postulate if the source would be physically able to hear and see what happened on the court. As a result of his research, Sappenfield provided quotes of what Williams said, filling in that piece of the puzzle for us.

Next, it is important to note how Sappenfield’s approach to the story and style differs from Robbins’ approach. As you recall, Robbins’ coverage largely compared Williams’ behavior to her competitor, Clijsters. Sappenfield places Williams’ “spectacular meltdown” within the broader history of players being driven “over the edge” by foot-fault calls.

By focusing on similar behavior exhibited by other players, Sappenfield gives us more information about the culture of tennis. Perhaps the author’s biggest insight is that there is an unspoken rule that foot-fault infractions are not called during pivotal match moments, such as Williams’ serving match point (or being one point away from losing). Learning how other players have literally protested officials for making such calls at “important moments” helps us understand that Williams’ behavior is maybe not as anomalous as we initially thought.

Sappenfield’s placing of Serena Williams’ reaction in this broader context of tennis culture and players’ expectations and behaviors does not invalidate Robbins’s coverage of the event. But if it is so common for players to get upset over untimely foot-fault calls, why was it such a big deal that Williams acted this way? It might make us wonder if Robbins treated Williams fairly in her coverage, or if she provided us with adequate context for the event.

What about a previous tennis match?

At this point, we should circle back to re-examine the tone in the Times article. We can see that Robbins did provide her readers some greater context, but focused on the history between Williams and Clijsters. This is something we have not garnered from other sources, so it can help us see the situation from this lens. Robbins details that Clijsters and Williams played against each other before at Indian Wells Masters in California. Despite the fact that Williams won the 2001 match, she has not played at Indian Wells since. Williams and her sister Venus have remained absent because the crowd hurled racial epithets toward them.

Even though Clijsters said the 2009 US Open was “a completely different situation” from Indian Wells, we can make a note that the crowd’s racist taunts left a lasting impression on Williams and influenced her playing decisions. To investigate Robbins’ reporting further, we can examine what other sources have to say about the Indian Wells match-up or the influence of race on Williams’ career in general.

To find other sources on Indian Wells Masters, we could check for previous work to learn more about the tournament or to see what was written at the time about the Williams-Clijsters match and related racial taunts. Or we could go upstream for a recording of the match to verify what happened. Finally, we would then read laterally to fact-check different cues.

For the sake of brevity, however, we will skip researching the Indian Wells tangent, and focus on reading laterally about the aspects of race and racism that Robbins touched upon. Again, we will take to Google.

Racism in tennis?

We could try searching for “Serena Williams racism.” This will give us a host of articles: another tennis player padded her shorts and chest in an imitation of Williams during a match, a former grand slam winner was once banned from tennis and fined for his racist comments about Williams’ unborn child, and Williams has argued for equal wages for black women in Fortune magazine. Anyone of these could be useful if we wanted evidence that Williams has encountered racism during her career.

We are specifically examining the 2009 U.S. Open, though. So we could add that to our search terms. Because we already have done one sweep of the 2009 US Open coverage when we retrieved The Christian Science Monitor article, we should strive to find a source that we wouldn’t ordinarily read. Scrolling through the results leads us to a post, Refereeing Serena: Racism, Anger, and U.S. (Women’s) Tennis, on “The Crunk Feminist Collection” blog. According to the headline and first couple of paragraphs, the post promises to dissect the roles that race and racism have played in the press’s coverage of the Williams sisters and in their tennis careers.

Before we dive into reading the article, we should first see if it is worth our while. Or if we think it might be credible. We will start reading laterally again, by checking out who wrote it and then the “About” section on the blog.

First, we can note that this post is filed under the anonymous name of “crunktastic.” To figure out who might be publishing under this name, we should hop over to the “People” section for a full list of staff and writers.

Here, we see a full list of contributors to the blog. None of them are listed under the name “crunktastic,” so we might assume that this posting was an anonymous post that was approved by the administrators of the blog. Skimming through the authors’ biographies, we read that many of the people identify as feminists and scholars. Most of them hold their Ph.D.s and professorships at prominent American universities.

Then we notice one of the two co-founders, Brittney C. Cooper, refers to herself as “Crunktastic” in her biography. So we have found our author! We see she holds a Ph.D. from Emory University and is an assistant professor in Women’s and Gender Studies and Africana Studies at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, and that she focuses her research on black feminist thought and black women’s intellectual history.

We then laterally search for Cooper to verify her academic appointment and to see what else she has written. This will help us confirm that she is a researcher and expert in the field of black feminism. We can confirm her department affiliations at Rutgers, take a peek at her Twitter account, and read an National Public Radio interview she had about dealing with racism before going upstream and landing on a primary source, her curriculum vitae (CV or academic resume) posted on her personal website.

Culling information from these sources, we can deduce that she has published a fair amount in her field. Though there is no evidence that she is an expert in tennis, she has written books and several articles on race, racism, and women, and even about how these areas relate to popular culture. NPR views her as a reliable source of information on these topics, and Rutgers recently gave her an award as well. Cooper has been promoted to associate professor at Rutgers as a result of her scholarship. We could use all of this as evidence that Cooper is an educated and reliable authority to address the ways race may have impacted Williams’s tennis career and performance.

Why did Williams react like this: The alternative perspective

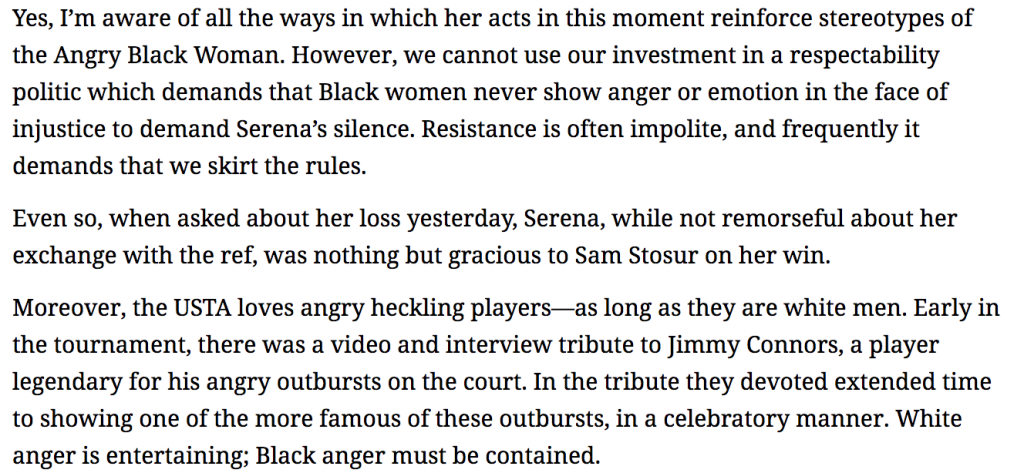

Let’s jump back to the blog post and read what “Crunktastic” Cooper has to say. Writing two years after the 2009 US Open, Cooper is responding to an incident at the 2011 US Open that reminded her of the match we are studying. During the 2011 tournament, Williams disagreed with a referee’s ruling. “Serena gave the ref the business for the next three games,” Cooper writes, because Williams mistakenly believed the referee was the same referee who “screwed me over last time.” Williams’ incorrect identification of the referee is beside the point, Cooper implicitly contends. The point of the situation is how Williams’ anger is depicted and interpreted by the press.

Cooper lays out how the press and US Tennis Association are much harder on Williams than on her white male peers, such as John McEnroe or Jimmy Connors, who also were guilty of having their own emotional outbursts on the court. To begin, Cooper summarizes that the press has a long history of labeling the Williams sisters as “hypermasculine, unattractive women overpowering dainty white female tennis players.”

Citing specific sports announcer and analysts, Cooper provides numerous quotes about the Williams sisters that focus on their physical strength while failing to acknowledge their intellect, but emphasizing that of white players. Drawing on her academic training, Cooper determines that Williams’s outbursts in 2009 and 2011 and the press’s portrayal of them could “reinforce stereotypes of the Angry Black Woman.”

Such misrepresentation of Williams, Cooper explains, feeds a narrative of white supremacy that is played out through officials and the press policing Williams’ behavior. To prove her point, Cooper cites the fact that Williams was levied the largest fine in U.S. Tennis Association history, $82,500, for the 2009 incident. This is a much larger fine than any of Williams’ white male predecessors and colleagues have received.

Cooper reminds her readers that in 2011, the tennis association seemingly celebrated one of Connors’ outbursts in a highlight reel at that year’s tournament. The author contended that the association wishes to curb and control Williams’ anger but essentially encourages white men to express theirs by celebrating them with highlight reels.

Cooper has a different take on Williams’s behavior. She argues that rather than an angry black woman who cannot control her emotions, the player should be understood as resisting the prejudices she has encountered as a black woman playing in a historically white sport.

In this sense, the press and the association are the ones who should be punished for furthering negative stereotypes of black players, specifically women. Williams’s arguments with referees should be understood as her striking out against such racial injustices.

This is a lot to digest, but Cooper gives us a perspective that has not been covered by any of the other reports we have read.

Cooper also leads us to circle back to Robbins’ New York Times article. With Cooper’s criticism in mind, we can take a second look at the language Robbins used to describe Williams and Clijsters, and begin to question her writing style.

The original article’s tone in context

In the opening passage above, we can see that Robbins used the adjectives “ugly and improbable spectacle” to describe Williams’ actions. She depicts Williams as “frustrated” and behaving “angrily” throughout the match as she whacked the net with her racket before appearing to “threaten” the judge.

Clijsters, meanwhile, is drawn as the “composed” player who “dominated Williams all night.” In the middle of describing the ways in which Clijsters remained calm and in control, Robbins lets it drop that Clijsters “is the mother of a toddler.” Why would Robbins mention this? Toddlers, going through a major development stage, are known for their tantrums.

The author’s description of Williams’ behavior focuses on the player’s anger, physical displays of frustration, and seemingly lack of control throughout the match. Is Robbins parallelling Williams’ behavior to that of a two-year-old having a tantrum? Clijsters, it is implied, was able to remain calm because she likely was used to such behavior from her toddler. Williams’ behavior, Robbins concludes, prevented Clijsters from celebrating her “joyful” return to tennis and her skilled play.

Notice some things? Thinking back to Cooper’s blog post about the portrayal of Williams as an “angry black woman,” we might have a new string of questions and ideas about the credibility of this Times article. Did Robbins unfairly portray Williams as an angry black woman? What does Clijsters’ motherhood and toddler really have to do with the match? Who did Robbins view as the skilled player in this match? Did Robbins appear to favor one player over the other? Why?

We found that Robbins provids us plenty of verifiable facts about the match. Williams did say something to the line judge, which resulted in her being assessed a penalty and losing the match. We had to seek out other sources to know what was said and to determine for ourselves if Williams did commit a foot fault.

But the author’s language may have us second-guessing if she treats Williams fairly in the article. She does focus a great deal on Williams’s anger and singularized it as unusual behavior. Sappenfield and Cooper maintain that white men have a long history of getting angry on the court with far fewer negative consequences from the tennis association and the media. Finally, Robbins does seem to emphasize Clijsters’ ability to control her anger and her skillful play, which might imply that Clijsters had some sort of mental and emotional superiority to Williams. This, we know, Cooper would fault as a plotline in a false narrative of white superiority.

Is This Article Credible Enough To Cite?

In the end, we very well could use the Robbins article in our writing, but note that it is not a perfect source. We could say that the substance of the article, or the fact that Williams lost the match after being assessed a penalty, is credible.

But we also discovered that other reporters were able to uncover more information by using different sources than Robbins. So we would need to supplement the article with other sources that provide greater detail about what Williams said, and, perhaps, our own reading of the call based on the recording of the game.

We might, moreover, question the tone of the article. To do this, we, again, would need to use different sources than Robbins. We could cite Cooper’s blog posting, or maybe dig deeper to read academic sources written by Cooper or other scholars about black feminism, the angry black woman stereotype, or race and racism in tennis. Based on this evidence, we might question whether Robbins was unfairly hard on Williams. Following Sappenfield and Cooper, we might even compare Williams’ actions to McEnroe, Connors, or other players who have lost their cool over a foot-fault call. All of this would provide our readers with greater context and understanding of the 2009 match between Williams and Clijsters.

Activity: Developing questions

Review this CBS Los Angeles article about college athletes earning money from endorsements and ad campaigns. As you read, formulate a list of critical questions to possibly research in order to evaluate the article’s credibility cues and overall credibility.

Activity: Test your source (and yourself)

Look at this Sportscasting article about a U.S. Open match between two other women’s tennis stars, Naomi Osaka and Coco Gauff. Using the four fact-checking moves discussed above, research the article’s credibility. Would you reference the Sportscasting article in your own work?