17 Scholarly Research

Karna Younger

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand the creation process and purpose of research studies.

- Articulate strategies for reading scholarly sources.

- Understand how the creation process and purpose of scholarly sources contribute to their credibility.

That Research Study Sure Makes You Look Smart

The jobs of communications professionals often center on consuming complex information, and translating it into advertising campaigns, press releases, or news articles that busy, average people can relate to, read quickly, and learn from.

As a communications expert, you will increase your credibility if you consult the work of other experts. As a college student, you probably have caught on to the fact that you are surrounded by experts, such as your professors, who research and produce scholarly information.

Journalists and strategic communicators can benefit from research studies in a couple of other ways. First, new research studies often present unique insights or information that isn’t general knowledge yet. Journalists looking for new story ideas sometimes will turn to freshly published research studies. Strategic communicators can get a leg up on the competition by reading new research about their clients’ fields.

Second, the authors of research studies and those they reference are ready-made interview subjects. Researchers are experts in their fields, and they usually are well-practiced in discussing their work, so they often can talk about their research it in a more succinct, friendly manner than their written work.

In this chapter, we discuss scholarly research studies like the ones that many of your professors produce. Research studies are known by many different names: scholarly sources, peer-reviewed sources, and academic literature, among others. We start by discussing peer-reviewed sources, and focus on how the creation process and purpose of research can contribute to their credibility. Then, we share strategies for accessing and reading research studies.

Scholarly Research Is a Conversation

University faculty, that is, many of the professors who teach your classes, spend their entire careers learning the everything of a topic, right down to the most boring details, which they find absolutely fascinating. They then publish journal articles or books based on their research.

Research studies don’t exist just so a bunch of stuffy people can bore the rest of the world. Many of your professors, librarians, and other members of the faculty are hired to research and produce scholarly material. Why? Because universities are about the production of new knowledge. Universities are measured by the research output (articles, books, patents, etc.) that their faculty members produce, and by the research funding they generate. As a result, many of the things that make our lives easier and richer today were invented through university research, as this article in The Atlantic magazine enumerates.

Academics write for each other and for the rest of us at university. Over the course of their careers, academics write and publish their work so that other experts can read and respond to their findings by publishing their own work. This publishing practice creates a scholarly conversation and a community.

Most members of the public do not participate in this conversation. As a university student who produces his or her own research, however, you do participate in this conversation. All members of this scholarly community strive to uncover problems and solutions, which are seemingly endless, because new problems, evidence, and possible solutions are always popping up.

One way to plug into this ongoing conversation is to pay attention to the citations that authors use in their research. These citations indicate to whom an academic piece of writing is responding. When your English and history professors ask you to cite your sources, they are really asking you to show the scholarly conversations that your writing is a part of. Citations allow readers to locate and read the same sources as the authors of academic writing, so that they, too, can participate in this scholarly chit-chat. Scholarly research articles and their citations give readers a deeper understanding of a topic.

All research studies share a larger purpose of educating people who are engaged in a scholarly conversation. Let’s examine the process and purpose of research studies more closely using the characteristics we introduced earlier, including purpose, research, length, editing, time, and ease of creation.

How to Recognize Good Research: Format as Creation Process

The world seems full of research, and it’s sometimes hard to tell the good stuff from junk science. Librarian Kevin Seeber recommends focusing on the creation process of information to determine its credibility. We also recommend that you use this process to identify and evaluate research studies.

Seeber suggests considering several factors of the research and publication process to determine information type: the time it took to research and publish the piece, the amount or quality of research conducted before writing it, the editing process, the length of the piece, and how easy or difficult it was to create the piece.

You could use a scale that considers all these factors to determine how the different information sources you encounter, like tweets, Wikipedia postings, articles of all types, and books, stack up against each other. Chances are you are doing a version of this already.

The other element that helps us evaluate the creation process of information, and to assess its credibility, is the information’s purpose. In other words, determining why and for whom the information is published. Thinking through the creation process goes hand-in-hand with thinking about the information’s purpose.

To get a better sense of these concepts, let’s use this evaluation process to analyze a tweet, and then compare this to an evaluation of a scholarly article.

Example 1: A breaking news story

Let’s walk through a breaking news story to get a sense for how this whole “format as a creation process” works. Exhibit A: An article about a shooting in Lawrence, KS, written by Nicole Asbury, a reporter for The University Daily Kansan (UDK).

Let’s walk through evaluating this news story using the criteria we introduced above. In order to better understand Asbury’s process for researching and writing the piece with one of her colleagues, we interviewed her over email. The below is based on her responses.

Purpose. Why and for whom did the Asbury create this article? The purpose of the article was to inform members of the University of Kansas (KU) community of “potential danger in Lawrence and the possible loss of a community member,” Asbury said. Someone broke the law “a few minutes away from campus,” so Asbury knew UDK and its readers would be interested in the news.

Research. Asbury’s research process reveals how quickly reporters must work to gather facts and what late hours they must keep to do so. Asbury’s research started at 10 pm when she caught news of shooting while listening to the police scanner. While her colleague Adam Lang monitored the police scanner, Asbury headed to the scene to witness events and gather information to inform her questions for police. The police spokesperson responded in the middle of the night, and Asbury followed up with the spokesperson before publishing the article in the morning. It is important to note, however, that the story continued to unfold after Asbury published her article.

Length. The article is 96 words. Breaking news stories are often shorter because there is scant information as a story unfolds.

Editing. Usually an article at the UDK goes through “three stages: content-editing, copy-editing and slotting,” Asbury said. Because this news article was so timely, though, Asbury’s article underwent a slightly different editing process. She and her colleague Lang wrote and edited it through Slack before the editor-in-chief edited and published the article.

Time. Asbury found researching this article took a bit longer than usual. Typically, “quick news” takes about 20 minutes of her time, but this one took about 12 hours. To recap: Asbury started at 10 pm with the police scanner, and then took a nap after staying up until 2 am to communicate with police. After she woke up at 9 am, it took her about five minutes to polish off the article.

Ease of creation. “Breaking news can be tough,” Asbury wrote, “but once you do it enough, you learn how to write quickly and accurately. The process doesn’t change, since you’re talking to the same people.” Because Asbury is a pretty experienced reporter, this article was “fairly easy to get together.”

Summary. We determined that Asbury’s article required some very late hours and hustle to research and write the piece. Asbury’s work is valuable because she was present at the crime scene and directly spoke with the local police. Additionally, with a quick research, writing, and editing timeline, Asbury’s article provided timely and accurate information available at the time of publication. Because the story continued to unfold after Asbury published her piece, however, there may be more current information about the shooting and the police investigation. Finally, the article is not an in-depth piece because Asbury needed to publish it quickly. There may be other information sources that provide a deeper understanding of related topics, such as the crime rate in Lawrence.

To gain such deeper understanding of a topic, you will need to consult sources that have been developed over time and with more research.

So, next, we use the same evaluation criteria to assess a peer-reviewed article. It is important to note that you do not have to speak with the author directly to evaluate a source type. Consider the differences between these two sources, and why your professors insist that peer-reviewed sources are good sources of information.

Example 2: A peer-reviewed article

We illustrate the process of creation and purpose of peer-reviewed research with this article: “Eyes Wide Shut: Failures to Teach Student Journalists about Eyewitness Error.” The article is written by Robin Blom, an associate professor of Journalism at Ball State University, and published in the Journalism & Mass Communication Educator journal, which is published by SAGE Journals. (We found this article by searching for “eyewitness AND reporting” in the database Communication and Mass Media Complete.)

Length. Most peer-reviewed articles are pretty lengthy. Peer-reviewed articles may have an abstract, introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, conclusion, and references. Not all of the sections may be present or labeled such in every article, especially if it is a humanities article. But all of these sections and the works cited or references sections can add up to 15 or 25 pages.

Our Eyewitness article is shorter than the typical length. It is 13 pages of heavy text and citations.

Research. The authors of peer-reviewed articles must be transparent about the research they document. They usually will list the works cited or consulted at the end of their articles, and fill their pages with footnotes, endnotes, or in-text citations. They do this to properly credit ideas to their original authors, and to demonstrate their own knowledge of a larger scholarly conversation.

Other indicators of research in a peer-reviewed article may be a literature review and a discussion section of the findings. If an experiment or another measurement was conducted, there will be details of the research methods, and tables and charts illustrating the results. While all peer-reviewed articles will cite other works to prove that they are engaged with a scholarly conversation, these other elements may not be present or clearly labeled. What matters is that there is evidence that the author conducted research.

Let’s take a look at our Eyewitness article. There are in-text citations and more than a page of references. Although scholarly articles may typically have distinctly labeled sections for the literature review and discussion, Blom uses subject headings instead. His literature review is divided under Truth and Accuracy, Eyewitness Error, and Textbooks. Blom really begins his discussion under Eyewitness Issues in Textbooks. Blom’s literature review is divided by subject to better help his reader understand the different but related scholarly conversations he is drawing from to create his argument. By discussing and citing other authors’ works, the author clearly communicated that he was informed of the latest research, that he was participating in greater scholarly conversations, and that he contributed his own original research to these conversations.

Editing. After researchers write, re-write, self-edit, and ask a buddy to look over their article or book, they often submit it for publication at a university press or in an academic journal. At least two other experts in the same field, called referees or reviewers, read the manuscript. This is where the “peer-reviewed” in peer-reviewed research comes from. In many cases, the referees do not know who authored the article, chapter, or book, and the authors don’t know who their reviewers are. This is called a double-blind peer review.

Once they have read the manuscript, the referees tell an editor or publisher to reject, revise, or accept the article or book for publication. Acceptance rates at many peer-reviewed journals are as low as 5 or 10 percent. If the manuscript is accepted for publication, a copy editor then edits the article or book for writing mechanics and style. The publishing company that owns the journal or publishing house then prints or disseminates the work. These publishing companies often are large conglomerates, like Springer and Elsevier (more on them later).

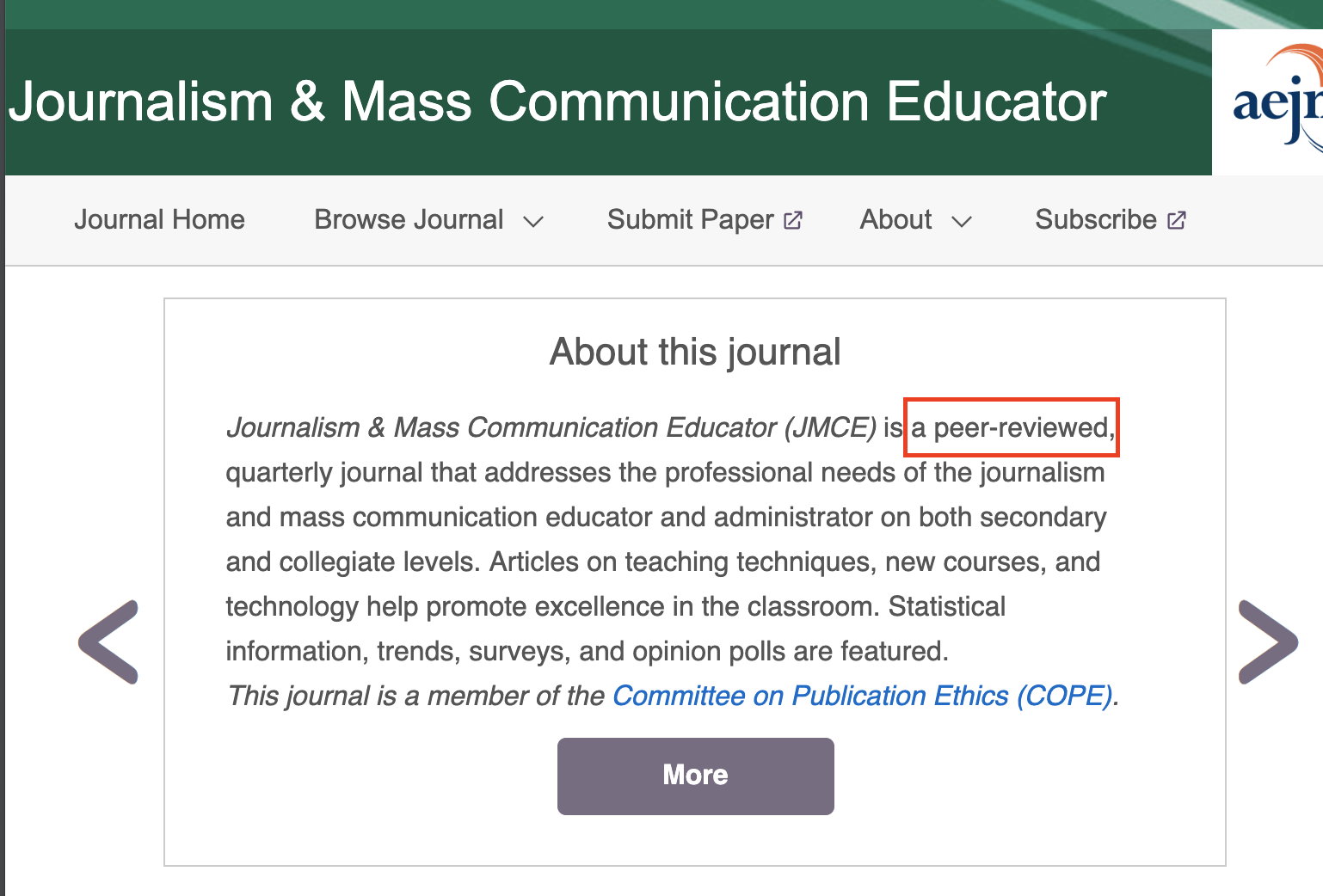

The Eyewitness article is published in a journal as opposed to a magazine, which usually means that it is probably peer-reviewed, and that it probably followed all of the steps we just listed. To make darn sure that this is a peer-reviewed source, we can click on the hyperlinked journal name in the database, or Google the name of the journal (that is, Journalism & Mass Communication Educator). On this page, we find information about the journal that identifies it as peer-reviewed.

If we want to learn more about the journal’s peer review process, we click on the link that says “Submit Paper” (in some cases you can look for “Instruction for Authors”) at the top of the website. The “Submit Paper” lists formatting and editorial procedures authors must follow to be accepted for review. At the very bottom of this page is a link for more information on “SAGE Manuscript Submission Guidelines,” which takes you to a page full of even more detail about the peer review process.

Based on all of these policy pages, we can safely conclude that the authors and reviewers did a lot of editing, both before and after the authors submitted the article to the journal, which was published and disseminated by SAGE.

If you don’t have time to click around a journal’s instructions for authors, a library database called Ulrichsweb indexes academic and non-academic journals. You can type a journal’s title into the database and see whether it tells you that the journal is “refereed,” which is its name for peer-review.

Time. It’s OK if you took a nap while reading our long section about the editing of peer-reviewed sources. You can only imagine how many naps authors have to take when they are living through the peer review and publication of their research. The publication process of peer-reviewed research may take years. Why? Because academics want to make certain that they know what they are talking about before they put it before a scholarly audience, who will go over the work with the most fine-toothed comb you have ever seen. So after researchers have spent at least a year developing and writing an article, it will go through the peer-review process, which can easily add another year. As a rough estimate, it can take at least two years to create a scholarly article. For a scholarly book, multiply that number a few times.

There are often clues in the article about how long it took the author to write it. For instance, they may mention what year they started conducting experiments. Plus, several journals will note when an article was first submitted for publication, how long it took the author to revise it, and, of course, the publication date. You can use this evidence to piece together a timeline.

How about our Eyewitness article? The author did not conduct an experiment and there is no notation of acceptance and revision dates. As a result, we are going to have to read between the lines. The best way to do this is to consider how much research Blom conducted to write the paper. If we flip to the end of the article, we can read a list of references that runs over three pages. Additionally, by scanning the article, we can discover more clues. In his introduction, Bloom wrote about his research process. First, he started with Google and had to sift through those results. Next, he searched in the library database, Communication and Mass Media Complete, but didn’t find any results. You might think this meant Blom didn’t spend as much time researching his topic in scholarly sources. On the contrary, finding zero results his first try means that he had to work even harder to locate three pages of resources. Finally, we read Blom’s methodology discussed under the Textbooks section. There, we discover that the author read 20 textbooks. In most semesters, you probably read about 4-5 textbooks a semester. But you always read every single word in your textbooks, right? Bloom likely did not read the entire textbook, though. Instead, he probably just read the sections that pertained to his research, so maybe he could bust through 20 textbooks in a semester or two. He probably needed additional time to select textbooks to review and to read his supporting research. As a result, we can probably assume that it took him at least a year to research and write this article.

Ease of creation. Typically, peer-reviewed articles are on the difficult side of ease because of the research, editing, and time that goes into creating them. In other words, as far as ease of creation goes, peer-reviewed articles are about the exact opposite of tweets.

Based on our discussion above, the Eyewitness article was probably pretty difficult to create.

Purpose. What is the purpose of the Eyewitness article? Lucky for us, the author was transparent about his purpose: “this essay is intended as a call to action for journalism educators and scholars to study an important aspect of journalism that has been overlooked in the classroom and in journalism and mass communication literature: eyewitnesses,” Blom wrote in his conclusion. Based on this statement, we can understand that the author’s primary purpose is to catalyze journalism educators to start teaching their students more about using eyewitnesses as a source. Additionally, Blom says he wants aspiring journalists to learn from professional journalists who use eyewitness sources. As a result, he is also writing the article to push professional journalists and journalism educator to work together to provide students with a better and more practical educational experience. Finally, since professors are evaluated on their research, publishing this study probably helped the author keep his university gigs and advance his careers.

Summary. Our Eyewitness article, similar to all peer-reviewed sources, involved a great deal of time, research, review, and editing. This is what differentiates peer-reviewed sources from other sources, such as tweets and daily news articles. The author of the article went through the grueling peer-review process geared to ensure that his final product would positively contribute to the scholarly conversation and community.

The peer-review process is intended to assure the reader of the author’s credibility. You probably have heard your professors extol the virtues of peer-reviewed sources. Some of them maybe even made you write papers using nothing but peer-reviewed sources.

The peer review part of the peer-review process is one reason why many professors hold these sources in such high esteem. It’s about quality control. Having at least two experts review a piece of writing and judge whether or not it should be published ensures, to a certain degree, the quality of the published research. Note, however, that this process is not fool-proof. You must rely on your own judgement and subject knowledge to determine if a source is credible.

If you are still fuzzy about the creation process and purpose of peer-reviewed scholarly articles, watch the following tutorial for more tips and information.

Accessing Research: The Big Business of Scholarly Publishing

Now that we know more about the value of research studies, let’s discuss how to access them. To do this, let’s first understand how academic publishing works. Watch the following video from North Carolina State University Libraries for a brief overview.

While this video discusses journal articles, journals, databases, and libraries, it says very little about the money that this academic publication process generates. For example, how much money does a journal’s publisher pay a professor to publish an article in its journal? The answer is nothing. Academic researchers get paid zero dollars for their published articles, and very little for every sold copy of a book they publish. Peer reviewers do it for funsies, too: they aren’t paid for their labor either.

The biggest publishers of scholarly literature are Elsevier, Taylor & Francis, Wiley, and Springer, including their subsidiaries such as Springer Nature. While these publishers do not pay authors for their work, they turn around and charge individuals and libraries hefty sums for access to the journals and books they sell.

These publishers also create their own databases that index their journals and journal articles. They then charge individuals and libraries for access to these databases. Because they control multiple databases, these publishers also create database bundles, and sell those to libraries. Think of bundling as a mystery box of databases that you may or may not need, but definitely will pay for. Such bundles may or may not be cost effective for libraries to buy.

Libraries pay a lot of money to subscribe to databases that contain peer-reviewed scholarly sources. In the 2017 fiscal year, the University of Kansas Libraries paid more than $1.1 million for the year’s subscription to databases from Elsevier and its subsidiaries, according to Angie Rathmel, associate librarian and head of acquisitions and resource sharing. Additionally, KU paid almost half a million dollars for Wiley database subscriptions. Some of KU’s bargain databases come from companies that only charge around $200,000 a year.

These access costs are rising, even though library budgets remain stagnant. As a result, many libraries are canceling their subscriptions. In recent years, KU has hit the decline button for its Springer bundle of databases. After ditching its $315,000 bundle, KU now only subscribes to select Springer journals, which saves the libraries more than $100,000 annually.

If you get the sense that there is something odd about the scholarly publishing marketplace, you aren’t alone. Think of how many colleges and universities there are in the country and in the world. Each is paying more or less than KU, which, as you can imagine, adds up. Elsevier pulled in just under 2.5 billion British pounds in the 2017 fiscal year, according to its parent company’s annual report. This publisher’s profit margin is higher than those of Google, Apple, or Amazon, according to The Guardian.

Did we mention that none of the creators of the content are paid for their work? “In effect, universities, and the public that supports them, are charged twice (and more) for research: once to produce the research and again to access it,” wrote KU’s Marc Greenberg, professor of Slavic Language and Literatures, and Ada Emmett, director of the Shulenburger Office of Scholarly Communication & Copyright, in a scathing indictment of the system. In other words, publishers like Elsevier aren’t exactly known for their generosity of spirit.

Peer Tutorial: Library Database Search Strategies

Click the image below to view a tutorial by Taylor Worden and Hayley Piatkowski (JOUR 302, fall 2019) on the best search operators to use in a library database.

Google and the paywall problem

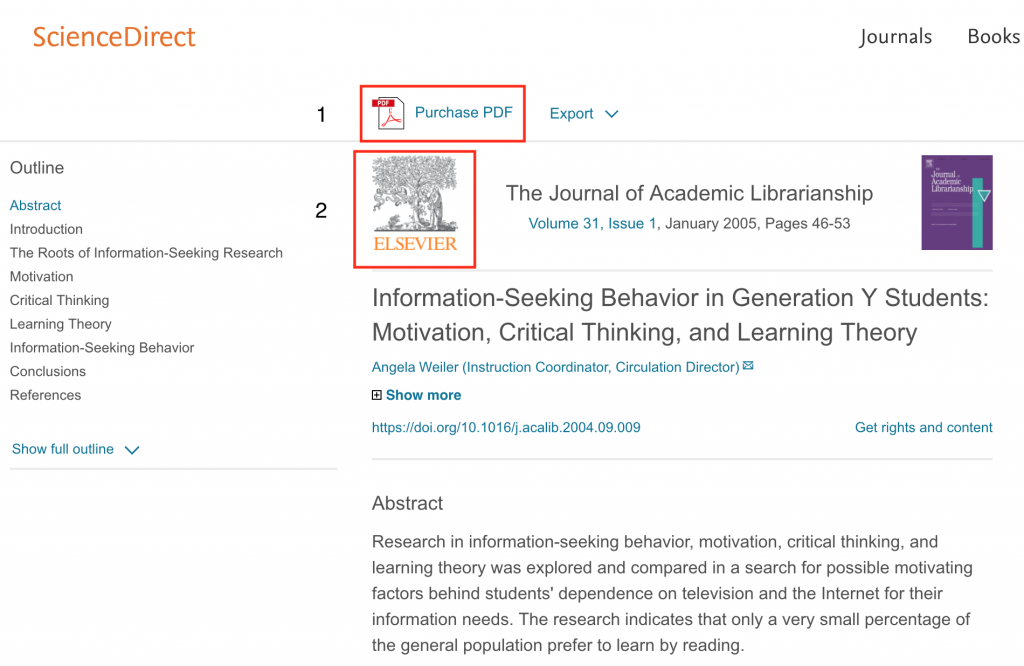

Scholarly publishers’ drive to make money is the reason why Googling usually doesn’t work when looking for peer-reviewed research studies. Take a look at the screenshot below. Does it look familiar?

It’s a paywall. While you may be able to use Google to discover that this article exists, you won’t be able to access the full article because it is hidden behind a wall that will come down only if you pay for it to do so. Access to this one article costs $35.95.

Fortunately, as a university student, you have the privilege of accessing these materials without having to pay $35.95 out of pocket. The answer to your problems is library databases, a type of closed source of information.

Closed Sources

“Closed” is a term applied to information that is housed behind a commercial publisher’s paywall. Many of the sources hidden behind these paywalls are research studies housed in library databases. Accessing these sources through your libraries’ subscriptions is key to getting past paywalls without coughing up your lunch (and dinner) money. Here we briefly discuss using library databases and Google Scholar to access closed research studies.

Library databases

As a student, you have access to the databases and scholarly literature to which your university’s library subscribes. At KU, all databases are available through the libraries’ website, under “Find” and “Articles and Databases.” You can then use the subject listing to target databases related to your topic, or access specific databases from the alphabetical list.

Here are some tips for using the databases:

- Refresh your searching skills by reviewing Search More Effectively chapter. You can customize your searches by using the operators covered there (e.g., quotation marks, AND, OR, etc.).

- KU Libraries has several tutorial videos that offer useful tips for searching databases.

- To make sure that you are searching scholarly or peer-reviewed publications, you can click “scholarly” or “peer-reviewed” on the left-hand side of your results screen. You can also look up the “about,” “for authors,” or “submissions” sections on any journal’s or publisher’s website, for descriptions of the publication process.

- Remember that citations are windows into an ongoing scholarly conversation. So if you find one good scholarly source on your topic, you have found found the mother lode.

- Pay attention to in-text citations and skim the works cited or references pages to identify other scholarly sources on your topic.

- Look up citations using the libraries advanced search option under the “Quick Search” on the libraries’ homepage.

- Enter at least two search criteria to get your article: ex. “Title” AND “Journal Name” or “Journal Name” AND “Author Name” or “Title” AND “Author Name.” Don’t forget to put the names of the journal or article in quotes to save time.

- If off campus, remember to log in using your university ID and password to get around our firewall (which we are required to have by good folks, like those at Elsevier, to prevent anyone not affiliated with the university from freely accessing the information).

Google Scholar

Google Scholar is a Google search engine that indexes some research and returns results of scholarly articles and books (and, if you want, patents and some legal cases). Many of the items indexed by Google Scholar are hidden behind paywalls, though, and many more not indexed by Google Scholar are hidden behind paywalls. This means that you likely will hit a paywall while using Google Scholar or miss out on an important work not available through Google Scholar.

If you want to use Google Scholar, that’s fine. But be smart about it. Access Google Scholar through the library’s list of databases. Doing so will sync up your Google Scholar search with materials available through the library. You may still hit a paywall if the library does not have access to a particular article, but your searching will go a lot more smoothly.

The following video presents tips on effectively using Google Scholar.

Peer Tutorial: Google Scholar

In this video, Natalie Ulfig (JOUR 302, fall 2018) demonstrates how to use Google Scholar.

Open Sources

Sources that are not hidden behind paywalls are commonly called “open” sources. Many open sources are available as a result of the open access movement, which works toward making information freely accessible outside the scope of the profit-making commercial publishers.

Open access supporters are working to make scholarly information as freely available as this textbook, so there is hope that one day we will be able to Google peer-reviewed articles and read them for free. When searching material that is open, you will find a mix of stuff, and the credibility of this stuff sometimes may be difficult to ascertain. This is why it is important to use the process of evaluating a study’s creation and purpose we introduced in this chapter.

Two open access tools include the Directory of Open Access Journals, which hosts peer-reviewed sources, and KU ScholarWorks, a repository for research and other materials produced at KU.

Directory of Open Access Journals

Some peer-reviewed journals publish materials openly and for free, without the help of the big, commercial publishers. These journals are of the same quality as those hidden behind paywalls.

The Directory of Open Access Journals is a good tool for discovering these journals. The directory indexes the content of nearly 12,000 open access journals that do not put up paywalls. Despite this large number of indexed journals, this should not be the only place you look because, unfortunately, not all journals are open. The Directory of Open Access Journals database is like other library databases, so use the same smart search strategies you use elsewhere.

KU ScholarWorks

Until all journals are published openly, authors and proponents of the open movement have developed institutional repositories to access peer-reviewed literature. An institutional repository is basically a website where scholars upload their stuff so that anyone with internet access can read it.

KU ScholarWorks is KU’s institutional repository. KU was one of the first universities in the nation to establish a repository for research publications, making the information open and freely available to anyone with internet access. KU’s open access policy asks KU scholars to deposit copies of their work in the repository, and it asks editors to open their journals. This means that whether or not an article was published in a closed (paywalled) journal, we should be able to access it freely.

KU ScholarWorks contains publications by faculty, staff, and students. There are a number of peer-reviewed sources, such as articles from open journals published at KU, and pre-prints of journal articles. Additionally, there are conference presentations, theses, dissertations, and more.

Searching KU ScholarWorks is pretty simple. Using the search box, just type in your keywords, or the name of an author, and roll. Keep in mind that other universities have their own repositories, so if you are looking for work by a specific author, look for a research repository at his or her institution, and search for his or her research there.

How to Read Research Studies

Reading scholarly information can be difficult at first, but there are methods to make this task easier. First, it is often best not to read a research study from beginning to end, like a novel. Rather, it’s easiest to read it out of order, in chunks, and at least twice, in order to fully understand it.

This sounds like it will take forever to read an article, but these methods will actually save you time. You will need to experiment with your reading preferences to figure out what works best for you. Below are some reading tips to help you do that.

First, recognize the formula of the article. Many research articles are written in a formulaic way. Sandwiched between an introduction and a conclusion is the meat or body of the paper, which lays out the author’s argument through a literature review, methods, results, and discussion.

Think back to a time when you wrote lab reports in a chemistry or a biology class. You might remember that your reports contained these same sections. These sections usually are clearly marked in science, medicine, and social science articles. Social science includes subjects like psychology, sociology, political science, and communication. Humanists (i.e., people who study subjects such as literature, history, art, culture, gender), however, may not label the sections of their works in this manner, and may only use the demarcations of introduction and conclusion.

Scientific articles

Here’s a visual representation of how a typical scientific, medical, or social scientific article is organized, and the order in which to read such an article. Here’s a step-by-step discussion of this process:

- Start with the abstract. This italicized paragraph is like a miniature version of the article and will give you all the big highlights: the background or larger scholarly conversation of which the author is a part, the author’s argument, and their findings or conclusion.

- Most of these articles report the collection of some new data. From the abstract, try to figure out how the data was collected, and who or what were the study subjects.

- The most-used data collection methods are experiments, surveys (or questionnaires), interviews, focus groups, observations, and content analyses. Your study used one or two of these.

- Most scientific and social scientific studies study people, but study subjects also can be inanimate objects, like laser beams or news articles.

- Articles that have the term “meta analysis” in the title or abstract are studies of other studies. They aim to establish what the research consensus is on a topic, that is, what most experts agree is true about a topic.

- After the abstract, look for hypotheses or research questions in the first couple of sections of the article. Hypotheses and research questions summarize the researchers’ goals in the study. They should give you a clear idea of the researchers’ focus. Look for “This article argues” or “This study aims to.”

- Read the beginning of the discussion section, which usually is the last major section in the article. This section again should summarize what the study tried to accomplish, what its results were, and what are the implications of these results. You can skip any subsections that list limitations or future research suggestions.

- If you want to plug into the larger conversation around the study’s topic, look through the citations listed in the literature review, or in other sections at the beginning of the article. This is where researchers establish what conversations their research fits into. Look for these citations at the back of the article in the references or works cited section.

Humanities articles

To read an article or book in the humanities:

- First, read the abstract, if there is one. This italicized paragraph contains the same loot as one in a scientific article.

- Read the introduction and conclusion until you understand their main points.

- Pay attention to any sentence that begins with something like “This article argues.” This is the author’s thesis statement or argument. Keep this in mind while dissecting the rest of the article and evaluating whether the author proved his or her argument.

- If you see a portion of the paper where the author is describing previously published books or studies, this is the literature review. Skip this part for now.

- Move onto the body of the paper, where the author is actually making their argument, not just stating it. Once you locate that, read this intensively until you have a good understanding of what the author is saying. Remember that this may not be labeled clearly as the discussion, so you may need to skim the article to figure it out.

- Next, read the literature review to gain an understanding of the larger conversation the author is engaged in, and to identify possible sources to use in your own research.

- Finally, you can read the whole thing from beginning to end. Having broken down the article beforehand, this should go pretty quickly. Keep an eye out for any parts of the argument that you have lingering questions about, and read these parts more closely.

How to Evaluate Research Studies

In conducting a credibility assessment of a research study, draw on the evaluation criteria and methods we outlined and practiced in previous chapters: Evaluate Information Vigorously, Go Lateral With Cues and Evidence, and Tap Into a Credibility Network. In addition, here are a few credibility considerations that are unique to assessing research studies.

Creation process

At the beginning of this chapter, we wrote about evaluating the credibility of research by thinking about how it’s created. We used these considerations: how long it took to conduct the research and publish it; how much research was conducted, and what was its quality; the extent of the editing process; the length of the research report; and how easy or difficult it was to create the piece.

In general, the longer the research takes, the more hoops a researcher has to jump through to conduct the research, and the higher the barriers that the researcher has to clear to get the research published, the more credible the research tends to be.

In this chapter, we compared these characteristics in a tweet and in a peer-reviewed published study, and decided that the peer-reviewed study was more credible than the tweet. But the correlation between these characteristics and the credibility of research isn’t always as direct. So, it’s important to consider other elements of each study.

Verify the author’s credentials

Most peer-reviewed studies are written by college professors or graduate students who have expertise in the field about which they are writing. You can verify their credentials by Googling one of these variations:

- Google the author’s name;

- Google their name and their place of employment;

- Google their name and use the “site” operator, limiting it to educational institutions (i.e., “Jane Doe” site:edu);

- Look up the author’s name in their university’s directory (usually located on a university’s homepage).

Consider the author’s degree, education focus, and experience. That is, an author with a doctoral degree has more education than an author with a bachelor’s degree, and the amount of education can affect credibility.

It also may be worthwhile to compare the field in which an author got their education, and the research topic. The more overlap there is between a researcher’s education field and the topic of the research, the more credible the research may be.

Finally, the longer someone has been a researcher, and the more research their has published, the more credible they may be.

Once you have found sufficient evidence, you may summarize it along these lines: “Jane Doe obtained her PhD in public affairs and administration in 2007 from such-and-such university. Since then, she has taught undergraduate and graduate classes on X. Additionally, she has published several articles on X in Journal A, Journal B, and Journal C. Such credentials indicate that she is a credible source of information on X subject.”

Read and evaluate citations and works cited

If you notice that authors cite many of the same sources, there is a reason for this. Frequently and commonly cited sources are called seminal works. Seminal works are ones in which a major finding is presented or challenged. Authors cite seminal works to demonstrate their credibility, that is, that they are well informed, and engaged with the major issues in their research field.

In order to be an informed and credible researcher yourself, you should do the same. Use Google Scholar or the library’s main search function to locate commonly cited sources, and read and include seminal works in your research.

Evaluate the argument and evidence

This is probably the most difficult thing to do when learning about a new topic. Have faith in your own abilities to judge a source’s credibility, though. Here are some tips:

- Question an author’s evidence. Scholars must back up their opinions with facts. Make certain that they are fairly representing their research. For example, if the author is studying college students’ attitudes about X, make certain that they interview or survey college students to directly seek their opinions. If they only talk to parents of college students, the author is misrepresenting their work.

- Compare arguments. If two of your sources make argument A and one makes argument B, consider the evidence they use and decide which one seems most plausible to you. Just remember to back up your decision with evidence as well.

- Check the representativeness of their research.

- Double check their sources. If four of your five sources all cite and rave about a particular publication in their literature review, that probably means that is an important work. If your fifth source doesn’t cite this source, it could be an indication that the scholar is not the most knowledgeable authority on the subject.

Conclusion

Research studies are available through library subscription databases and freely on the web. There are closed and open research studies, which refers to how people access the information.

If the information is behind a paywall, it is closed, and best accessed through a library database. If it is open, it is freely accessible through an open access journal site, the Directory of Open Access Journals, or an institutional repository. Using Google or Google Scholar is possible, but you may hit a paywall, or not discover all of the information that’s available. This is why it is best to search a mix of resources.

Research studies can be pretty dense, so it is important to take time to read, re-read, and digest them. Don’t read beginning to end, and focus on the key information of each.

Finally, if you have found one good scholarly article, you probably have found 10 to 20 more. Scholars explicitly refer to each other’s work throughout their publications and include a list of citations at the end. Track down and use these cited sources in your own work.

Activity 1: Search

Use one of the resources listed in this chapter to search for research on a topic in which you are interested. Locate and read one scholarly source and write a one-page synopsis of your findings.

In the first paragraph, summarize the article, the author’s argument, evidence and how it is used. In the second paragraph, detail why the information will be useful to your project, how it relates to other information you have found, and how it will support your argument. If you disagree with the author, explain why, and support your explanation with evidence.

Activity 2: Open pedagogy

Create a tutorial for one of the tools for locating research studies listed in this chapter. Explore the tool’s search functions, information, ease of use, limitations, and other positive and negative features.

Using your findings, create a tutorial that demonstrates how to use the tool. Your audience for the tutorial is one of your fellow classmates. You may use whatever technological tool you wish to create your tutorial, which should run approximately 2-3 minutes.