16 Nonprofits

Peter Bobkowski

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand nonprofits as potential sources of information and expertise on a topic.

- Be familiar with several categories of nonprofits.

- Know how to find a nonprofit related to a specific topic.

- Be able to evaluate the credibility of a nonprofit using information from a Form 990.

Beyond Homeless Puppies

This chapter’s primary goal is to convince you to consider a nonprofit organization as a potential source for any news article, news release, or strategic communication report you write. In other words, as you plan your sources, I always want you to ask yourself, “Is there a nonprofit I can contact about this issue?”

This may seem like a strange goal because, if you’re like me, the word “nonprofit” conjures up images of sad-looking puppies and kittens, and Sarah McLachlan crooning, “Will You Remember Me.” Or appeals to “text such-and-such” to some five-digit number, for an automatic $5 donation to a natural disaster relief fund.

So this chapter’s secondary goal is to stretch your definition of a nonprofit beyond charities. Charities like the Humane Society and the Red Cross constitute only one category of nonprofits. There are many, many nonprofits that are not as well-known as these charities because they do not solicit donations from the public, and because they do not run vivid funding campaigns that pull at our heart strings.

For the purposes of this chapter, let’s use this definition of a nonprofit: A nonprofit is an organization of people who come together around a common cause about which they care deeply.

Nonprofits In the News

Let’s consider three examples of nonprofits being used as sources in news stories.

First example: Women CEOs

An Associated Press article published in USA Today and other outlets, discusses the relative absence of women CEOs in large companies. The article states that in 2017, women led only 5 percent of the top 500 companies traded on U.S. stock exchanges. It also reports, however, that these women were being compensated on par with, or more than, men CEOs. The bulk of this article is based on an analysis that a research firm named Equilar conducted for the Associated Press.

About two-thirds down, the article states that, “There is a bright spot, though: female representation on boards is improving, according to Catalyst, a nonprofit that works with companies to build a diverse workforce.” A couple of paragraphs down, there is a quote from a Catalyst vice president, who argues that this change is not generational, but driven by the recognition that diverse boards of directors are better for business than all-dude boards.

Our definition of a nonprofit as a group of people who come together around a common cause can help us understand why Catalyst ended up being a source in this article. Catalyst is an organization whose common cause is the promotion of a more gender-diverse workplace. It is likely that this story’s writer looked for a source that could provide some context or additional information about women as CEOs, or women in the workplace more generally. Catalyst fit the bill of such a source, and its vice president served as an expert voice in the story. The nonprofit also shared with the writer its own data about women on boards of directors. By including Catalyst in the story, the writer ended up with a richer report.

Second example: Employee perks

Another workplace-related story from the Kansas City Star describes efforts by companies to recruit millennial employees by offering them unique employee perks. The article’s sources are representatives of several Kansas City-based companies, including Cerner, Grant Thornton, Pro Athlete, and Black & Veatch. These companies’ unique employee benefits include gyms, cooking classes, phone plan discounts, and a breastmilk delivery service for traveling mothers.

The nonprofit source in the article is a group named American Student Assistance, which supports young people in their educational and career planning. One of the perks discussed in the article is assistance with student debt. The article cites research conducted by American Student Assistance, in which “76 percent of college students said such offers would be a deciding factor in accepting a job, as the average debt on a bachelor’s degree is around $30,000.”

The nonprofit plays a secondary but important role in this story, providing background information that the local company sources didn’t have. American Student Assistance, whose cause is educational and career planning, was a natural source to plug into an article about both career planning and, indirectly, college debt.

Third example: How these clowns suffer

An article in the Hollywood Reporter discusses the unintended consequences of the 2017 horror film “It,” about the murderous clown Pennywise. According to the article, the clown industry suffered following the movie’s release, with fewer clowns being hired for performances at schools, libraries, and birthday parties.

Key sources in the article are members of the World Clown Association, a nonprofit that supports clowns through conferences, training, and access to an insurance policy. Yes, clowns need insurance, and this isn’t medical insurance, but liability insurance. It’s to assist the clowns in case something goes very wrong during their performances. In the article, members of the association bemoan the negative perceptions of clowns that “It” and other negative media portrayals of clowns have generated.

How do the World Clown Association and its members become sources in this article? The writer of the article likely looked for a source that was well-versed on the plight of professional clowns, and one that could connect him to individual clowns who could witness to their struggles in the post-“It” era. The World Clown Association is a group of people who care deeply about clowns, and that fits precisely this writer’s needs for this story. And if nobody at the World Clown Association responded to the writer’s email or phone call, then maybe someone at Clowns of America International, another clown-focused nonprofit, would have been available.

In all three articles, nonprofits served as one of the sources because a nonprofit, by our definition, is a group of people who come together around a common cause about which they care deeply. When the article is about a nonprofit’s cause or issue, that nonprofit can be an ideal source. The people who work at the nonprofit, or the nonprofit’s members, are some of the most educated and passionate individuals on the issue at hand. They often have access to data and research that isn’t available elsewhere. And they know individuals whose first-hand experiences with the issue can contribute vivid details to the story.

In sum, a key question that a writer of an article covering any issue should be asking is: Is there a nonprofit whose cause is the issue I am writing about?

Categories of Nonprofits

While there are several legally defined categories of nonprofits, let’s consider a few common categories of nonprofits that may be especially useful as sources for journalists and strategic communications professionals.

Trade associations

A trade association is a group of people whose cause is their common trade, business, or industry. Trade associations often are formed by companies, and these companies and the people who work for them constitute the members of these nonprofits. Trade associations organize trade shows, conferences, trainings, certifications, and publish newsletters or magazines. All of these programs are meant to advance their members’ trades or businesses. Trade associations also can hire lobbyists to advocate for their members’ interests with lawmakers.

Examples: The American Home Furnishings Alliance is the trade association for companies that make furniture. Airports Council International – North America is the trade association for the operators of airports, and for vendors who do business inside airports. The National Association of Convenience Stores and the Association of Convenience Store Retailers both are trade associations for the owners of convenience stores and the suppliers of stuff that’s sold in them. The Kentucky Blueberry Growers Association is the trade association for blueberry growers in Kentucky.

Professional organizations

A professional organization (or society) is a group of people whose cause is their common profession. Whereas trade associations tend to focus on companies and industries, professional organizations focus on individuals. Professional organizations’ programming, however, tends to be similar to that of trade associations, often consisting of certifications or accreditations, continuing education, conferences, publications, and lobbying.

Examples: Each of the professions listed in this book’s title has a nonprofit professional organization associated with it: Society of Professional Journalists, Public Relations Society of America, American Advertising Federation, and American Marketing Association. Specialized professionals often have more specific organizations, like the Association of Health Care Journalists, ACES: The Society for Editing, National Association of Black Journalists and the Association of LGBTQ Journalists. The two clown associations mentioned earlier — World Clown Association and Clowns of America International — also are professional organizations. Other professional nonprofit organizations with which you may be familiar: American Bar Association, American Medical Association, American Psychological Association, and so on.

Labor unions

A union is a group of people whose causes center on the work conditions, compensation, and employment benefits of its members. Unions represent and advocate for their members in negotiations with their employers. Some unions double as professional associations. Most workers in the United States do not belong to a labor union, according to a 2018 Economic News Release from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Examples: The NewsGuild is a labor union for journalists and other communication professionals. The National Education Association is a labor union for teachers and other school employees. United Food and Commercial Workers is a labor union for food and commercial workers. Actors’ Equity Association is a labor union for actors.

Advocacy organizations

An advocacy organization is a group of people whose cause is an issue, broadly defined. These organizations support the advancement of their issues by means that are as varied as the issues themselves. Their programs may include education, advocacy for regulatory or legislative change, assistance with legal representation, days of action, volunteering, and promotion of the issue in the media and public discourse.

Examples: Catalyst and American Student Assistance, discussed in the news examples above, fall into this category. Some of these organizations are massive and known nationally, like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Others are tiny and local, like Friends of Lawrence Area Trails (FLATS).

Foundations

A foundation is a group of people whose cause is the financial support of some issue or entity through fundraising and/or the stewardship of investments. Private foundations, like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Ford Foundation, or the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation are endowed by families or corporations, and use their funds to support causes they like through grants. Community foundations, like the Lawrence Schools Foundation or the University of Kansas Endowment, solicit donations from individuals who care about the entities these foundations support.

In sum, depending on the topic at hand, an organization from one of these categories — trade associations, professional societies, labor unions, advocacy organizations, or foundations — can serve as an insightful source for the article or report on which a journalist or strategic communications writer is working.

How to Find Nonprofits

In Chapter 3 of this book, we covered the use of operators in Google searching, including the site: operator that can narrow down search results to specific domains. Because the extension .org stands for organization, many nonprofits use URLs that end in .org. Therefore, one way to look for a nonprofit on Google is to type the issue in which we are interested, and follow this with the site: operator and the .org extension. For example, the search

journalism site:org

results in links to a number of journalism-related nonprofits: the Pew Center’s website on journalism research (journalism.org), American Press Institute (americanpressinstitute.org), Columbia Journalism Review (cjr.org), the Poynter Institute (poynter.org), and Society for Professional Journalists (spj.org).

A problem with this approach is that the nonprofit Wikipedia, one of the most popular websites on the internet, uses the .org extension. So the site:org search inevitably brings up a bunch of Wikipedia entries related to journalism. To clean this up, we can use the – (minus) operator, and eliminate Wikipedia pages from the search results. The search

journalism site:org -site:wikipedia.org

returns results that do not include Wikipedia pages.

Another problem with this approach is that some nonprofits’ websites do not end in .org. For years other top level domains have also been used by nonprofits. For example, The World Clown Association website ends in .com (worldclown.com), the American Home Furnishings Alliance website ends in .us (ahfa.us), and the website of the Kentucky Association of Collegiate Registrar and Admissions Officers ends in .net (kacrao.net).

Also, in 2015, a new top level domain .ngo was introduced for exclusive use by nonprofits. NGO stand for non-governmental organization. So the site:org search may miss some nonprofits that do not have the .org extension in their URLs.

In addition to using Google, it is also possible to search specialized databases of nonprofits. Several organizations maintain such databases, including GuideStar, ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer, Charity Navigator, and Charity Watch. The following video walks you through using GuideStar to find a nonprofit that’s related to a specific issue.

How to Evaluate a Nonprofit’s Credibility: Bias

Every nonprofit is biased, and this bias should be identified when evaluating a nonprofit’s credibility. A nonprofit’s cause for being points to that nonprofit’s bias.

What is the bias of the World Clown Association?

This nonprofit’s cause is clowns and the need to support the clowning profession. Given this cause, this organization would never say that clowns are creepy, or that clowning is a waste of time and a worthless profession, or that it’s not a profession at all. In other words, the nonprofit’s bias is what it would never say about its cause. Doing so would undermine the organization’s reason for being.

What is the bias of the Association of Convenience Store Retailers?

This nonprofit cares deeply about the financial well-being of convenience stores and its operators. What would it never say? It probably would never say that convenience store prices are ridiculously high, that its products are subpar, and that through the processed food and tobacco they sell, convenience stores contribute to various avoidable health problems. Doing so would undermine convenience store profits, and the organization’s reason for being.

Expect every nonprofit to be biased. Identify this bias as you evaluate the nonprofit’s credibility.

Other Sources of a Nonprofit’s Credibility

In addition to bias, we can use other metrics to assess a nonprofit’s credibility. There are two obvious places and one less-obvious place to look for evidence of a nonprofit’s credibility.

The organization’s website is one obvious place to start. How much the organization says about itself, its leadership, its members, and its programs, and how current this information is, can provide clues about the organization’s credibility. The news is another obvious place to search. How an organization has been covered in the news and what about it has been newsworthy can be revealing about how credible an organization is.

Form 990

The less-obvious source about a nonprofit’s credibility is the organization’s Form 990, a financial statement that many nonprofits are required to file annually with the IRS to support their claim for tax-exempt status. One benefit of looking at the Form 990 as a source of credibility information is that an organization is obligated to report the truth about itself in this form.

Another benefit of looking at the Form 990 is that it is standardized, that is, from one year to the next, and from one organization to another, the form and the information it requests stay the same. This allows us to easily compare organizations historically and between one another.

The most transparent nonprofits will post their Forms 990 on their websites. Many nonprofits do not make these forms this easily accessible. Fortunately, GuideStar (and other databases) collect and make these forms available to the public. The following video shows how to access a nonprofit organization’s Form 990 on GuideStar.

How to read the Form 990

Like any tax form, Form 990 at first can be daunting to read. The trick is to know the four or five sections of the form to look for evidence of a nonprofit’s credibility. We discuss these sections below, using the 2015 Forms 990 for the World Clown Association and Catalyst, the workplace diversity nonprofit discussed in one of the news examples above. We include screenshots of the specific sections of the forms we discuss. Before you read the following, you may want to download the entire forms for yourself (they are 25 and 50 pages, respectively), and find each of the sections we discuss in these actual forms.

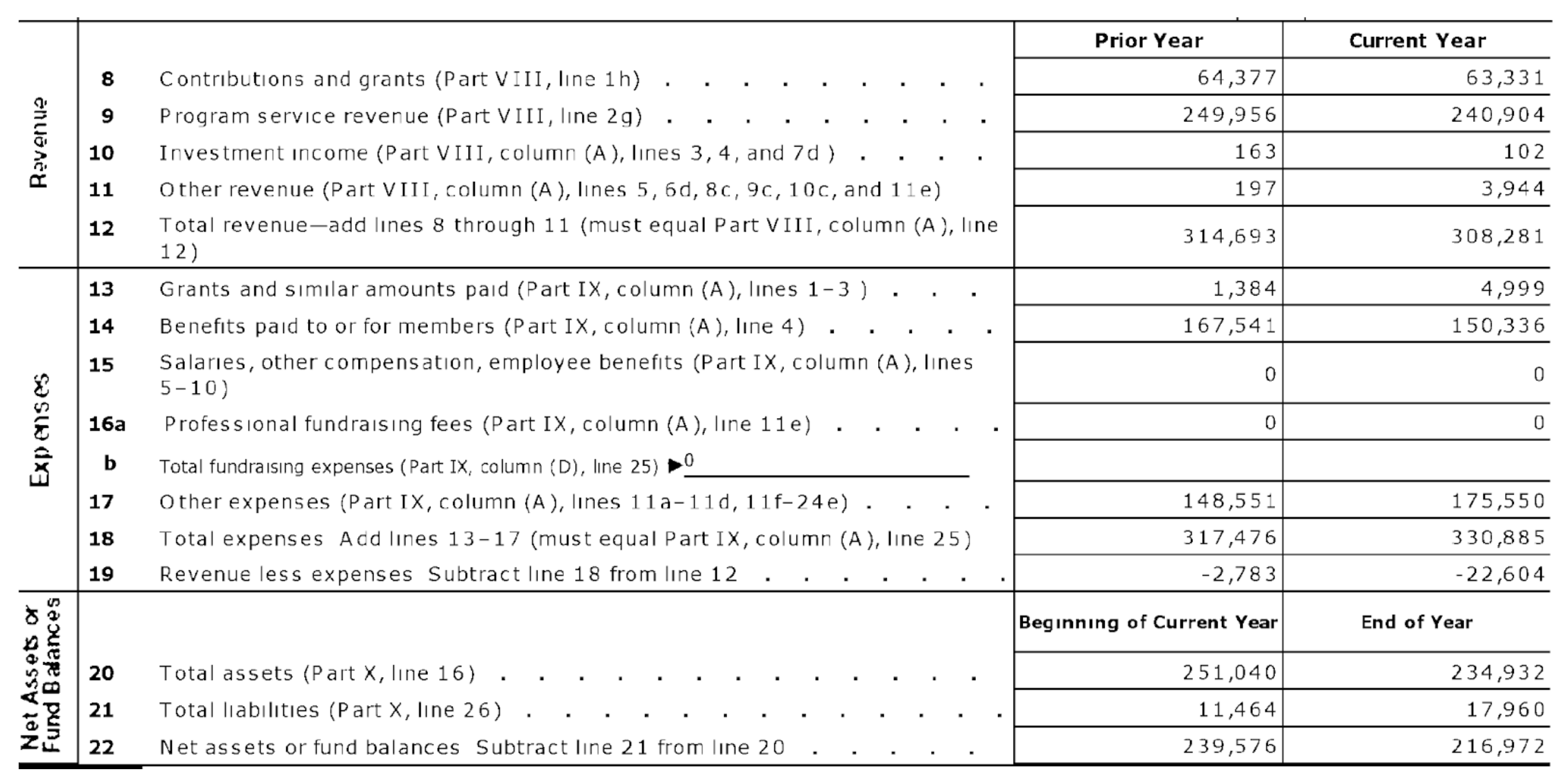

Part I: Mission and number of people

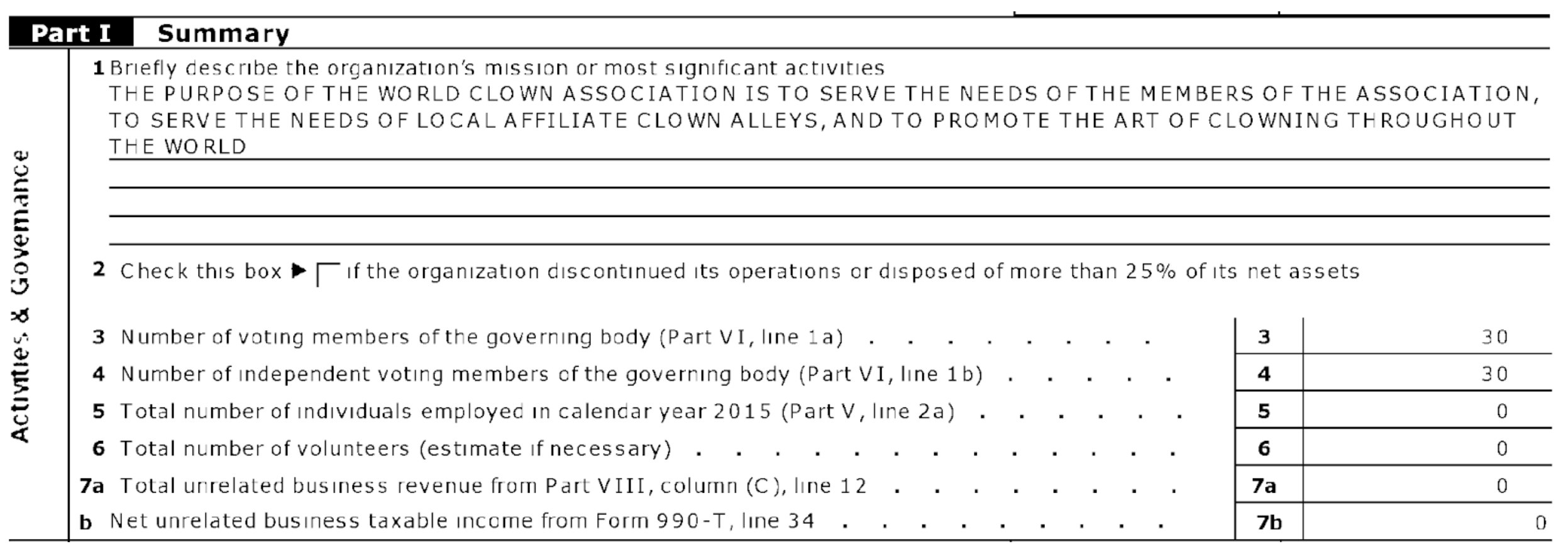

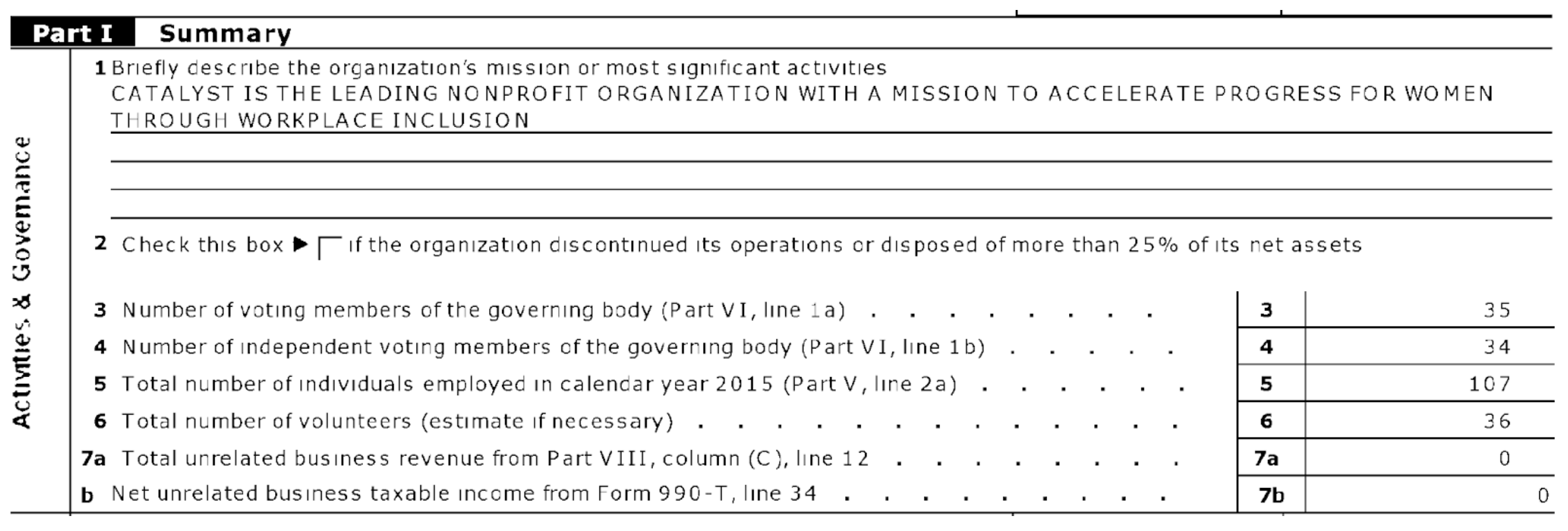

The first page of the form provides summary information about the organization and its finances. Let’s compare the “Activities and Governance” boxes of the World Clown Association and Catalyst. What is the main difference between these two organizations?

World Clown Association

World Clown Association

Catalyst

Catalyst

Other than the different missions of the organizations, the main differences are the numbers listed in lines 5 and 6, which denote the total number of individuals employed by each organization. World Clown Association says that it has no employees and no volunteers, whereas Catalyst employs 107 people, and has 36 volunteers. The other numbers, in lines 3 and 4, are similar — both organizations have about 30-35 people on their boards of directors, and most of these directors are independent, that is, not employed by, the organizations.

Part I: Financial summary

The next section provides a financial overview.

World Clown Association

World Clown Association

Catalyst

Catalyst

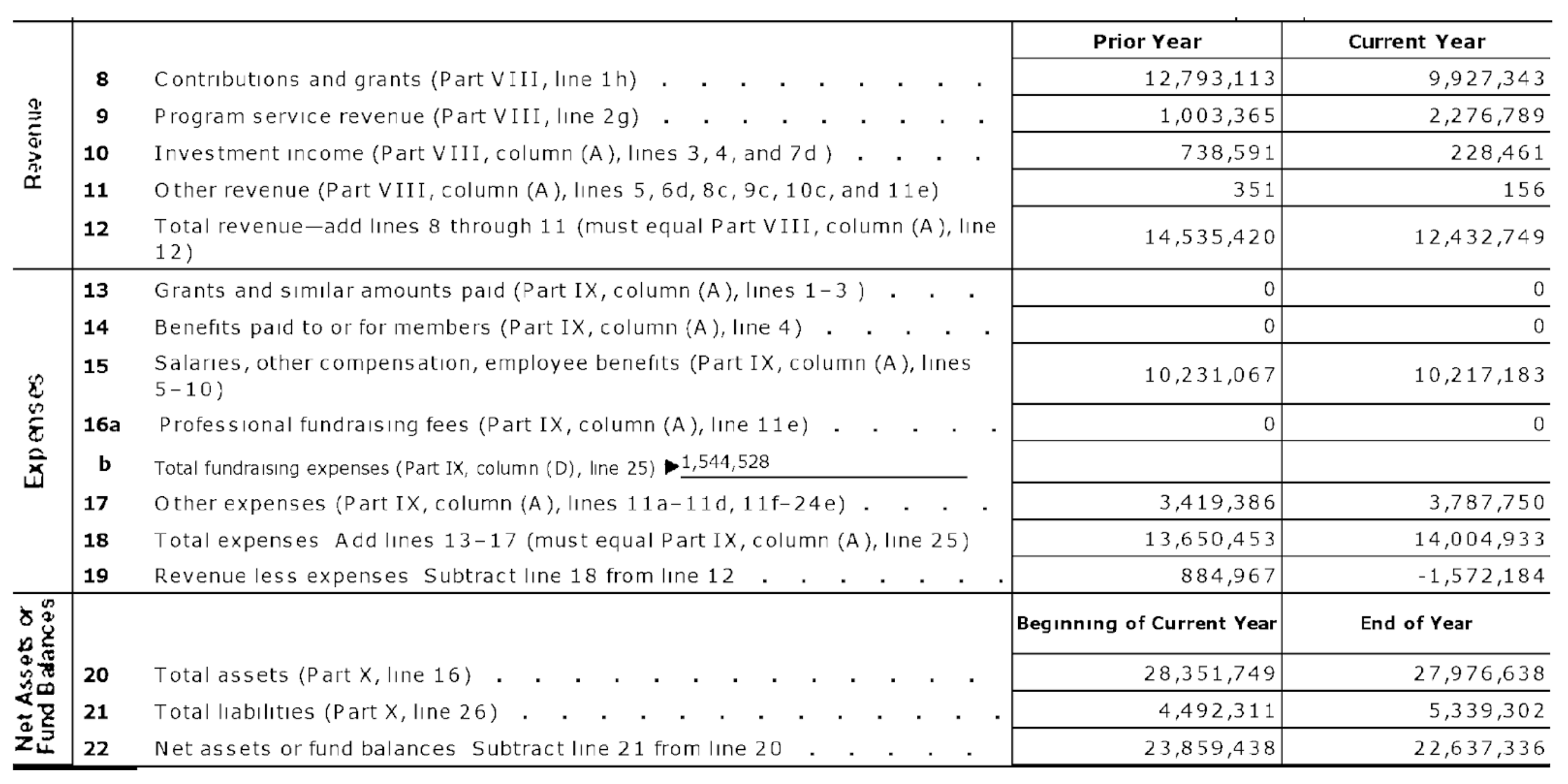

Let’s focus on one sub-section (or box) at a time, and examine the Current Year column on the right.

The Revenue box comes first. Line 12 shows the nonprofit’s total revenue for the year. A key difference between these two groups is their revenues. World Clown Association’s total revenue was $308,281. Catalyst’s revenue for the same year was $12,432,749. Catalyst brought in 40 times as much money as the World Clown Association. The lines above line 12 also reveal a key difference. World Clown Association makes most of its money ($204,904, or 66 percent) from the programs it organizes and runs (line 9). The rest of its money comes from contributions and grants (line 8). Catalyst’s revenue sources are the opposite. Most of its money ($9,927,343, or 80 percent) comes from contributions and grants, and the rest comes from its programs.

Do these differences in total revenue and revenue sources say anything interesting about the credibility of these nonprofits? Maybe, maybe not. It’s hard to make a clear credibility argument based on the size of revenue by itself. For now, we can conclude that the World Clown Association is very reliant on its programs to generate its revenue. Catalyst, meanwhile, relies on outside grants and contributions. This difference likely translates into what these two organizations say and don’t say about themselves and their programs to potential donors and members.

The next box presents an organization’s expenses. The World Clown Association spent $330,885, while Catalyst spent $14,004,933 (line 18). This means that both organizations spent more money than they brought in (line 19), which is called having a deficit. Does this say anything about either organization’s credibility? It suggests that neither organization was great at managing its finances, although the World Class Association’s deficit as a proportion of its revenue (7 percent) was smaller than Catalyst’s (13 percent). This evidence can be used in either organization’s credibility evaluation.

Can a nonprofit make a profit, by the way? Yes, absolutely. Catalyst’s financial summary, in the Prior Year column (line 19), shows that the organization had more revenue than expenses by $884,967. What happens to this leftover money? If Catalyst was a for-profit company, the owner or investors would share the profit, but because of this organization’s nonprofit status, no individual can take home this profit. A nonprofit’s profit stays with the organization, in its savings or investments account. Having some profit is desirable, so that an organization can add to a financial cushion it may need in a year when its expenses exceed revenues. At the same time, we would be justified to question the credibility of an organization that has huge profits but does not direct those to expanding its programs or benefits to its members or clients.

Before we leave this first page, let’s look at the amount of money that each organization spent on salaries and benefits to employees. Some charities have been accused of not spending enough of the donations they collect on the programs they say they organize. One way to gauge this is to consider what percent of an organization’s expenses goes to its employees (line 15), versus what percent goes to grants, programs, and member benefits (lines 13, 14, 17). Catalyst spent $10,217,183, or 73 percent of its expenses on salaries. The World Clown Association spent nothing on salaries. Could these numbers be used as evidence of either organization’s credibility? It depends on the organization’s mission, and the nature of its programs. But the figure 73 percent going toward salaries should raise a yellow flag, suggesting that we proceed with caution, and try to understand more clearly how this organization operates, before using this figure in an evaluation of its credibility.

Part III: Major programs

On the next page, in Part III of Form 990, the nonprofit describes three of its major programs, along with how much each program costs and how much revenue it generates.

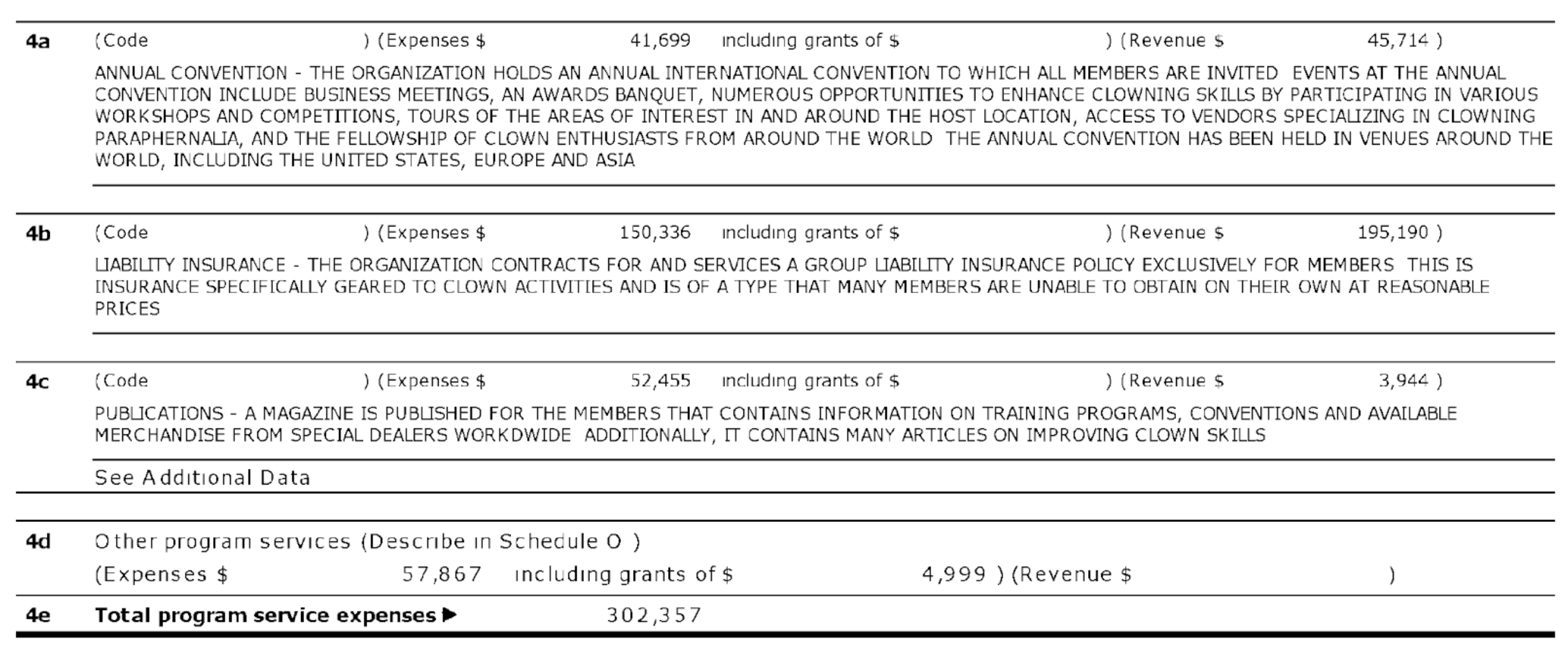

World Clown Association

World Clown Association

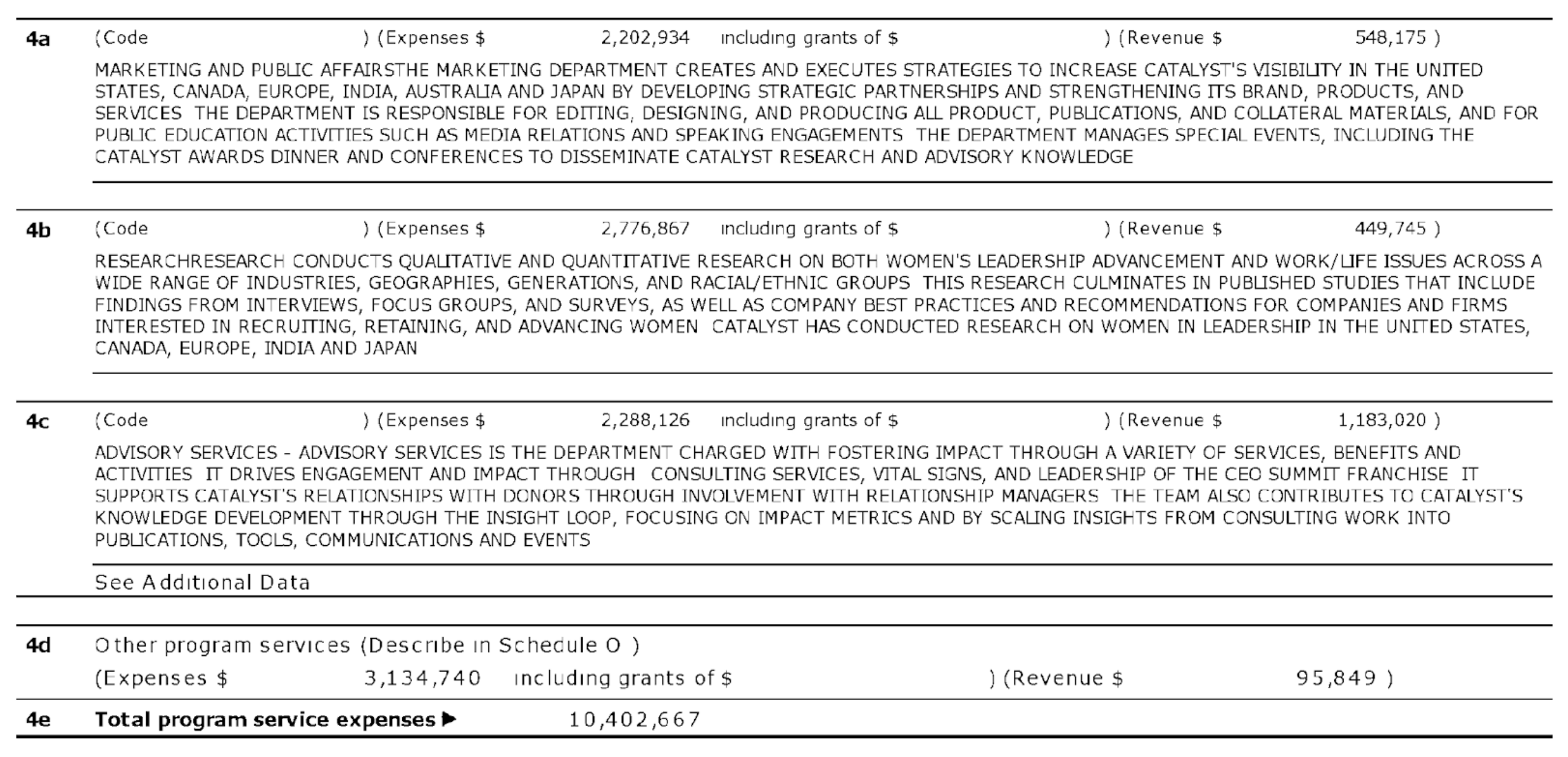

Catalyst

Catalyst

It’s worth reading through the descriptions of these programs to get a clearer sense of what each organization’s key programs are, and how much money is tied up in each program. World Clown Association’s convention (line 4a) and liability insurance (line 4b), for example, are revenue-generating programs. This means that the organization relies on these programs to support its other ventures that do not make money. This can influence how much the organization promotes and spends on these programs. This may be important context for evaluating its statements about these programs.

Part VII: Officers and top-paid employees

The next important section of the Form 990 is Part VII, which lists the organization’s officers and highest-paid employees. Before reading this section, it’s important to understand a typical nonprofit’s governance structure. Most nonprofits are governed by a board of directors (sometimes called trustees), which is led by a board chair or president. These directors typically do not work for the organization and are not paid by it. They have “real” jobs elsewhere, but meet regularly to make key decisions for the organization.

A main decision for many boards of directors concerns hiring an individual who leads the nonprofit’s day-to-day operations. This person might be called an executive director, a chief executive officer, or something similar. That person is a paid employee of the organization, usually drawing the highest salary. This executive also hires a staff to complete whatever tasks need to be completed. These staff members (e.g., directors, managers, assistants) also draw salaries from the organization.

While this structure consisting of a board of directors, executive director, and staff, is typical, there are many other nonprofit governance variations.

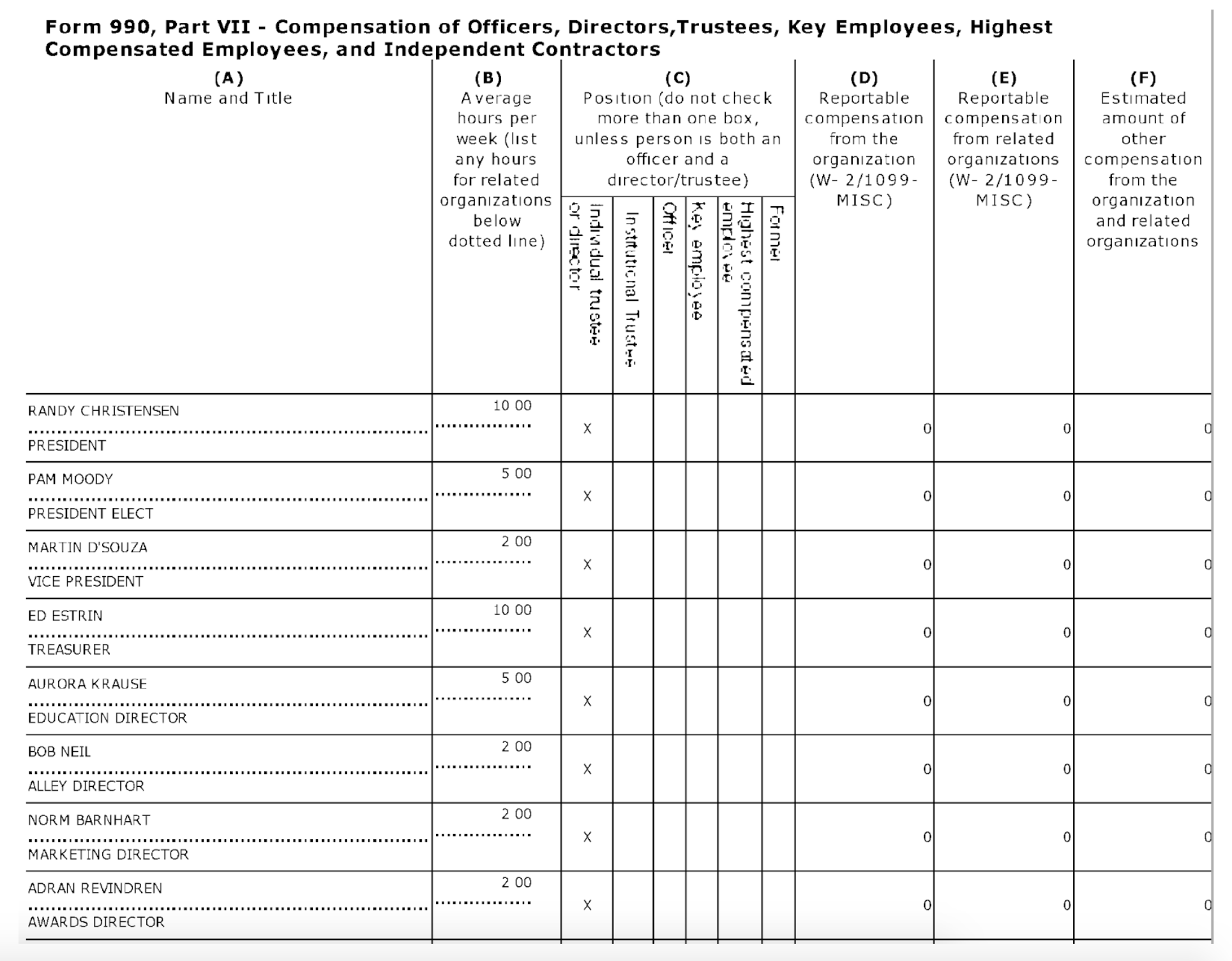

World Clown Association’s Part VII is three-pages long (below is the first page). It lists 30 individuals, none of whom work more than 10 hours a week for the organization (column B), with most working two hours a week. None of these individuals receive compensation from the organization or related organizations (columns D – F).

World Clown Association

World Clown Association

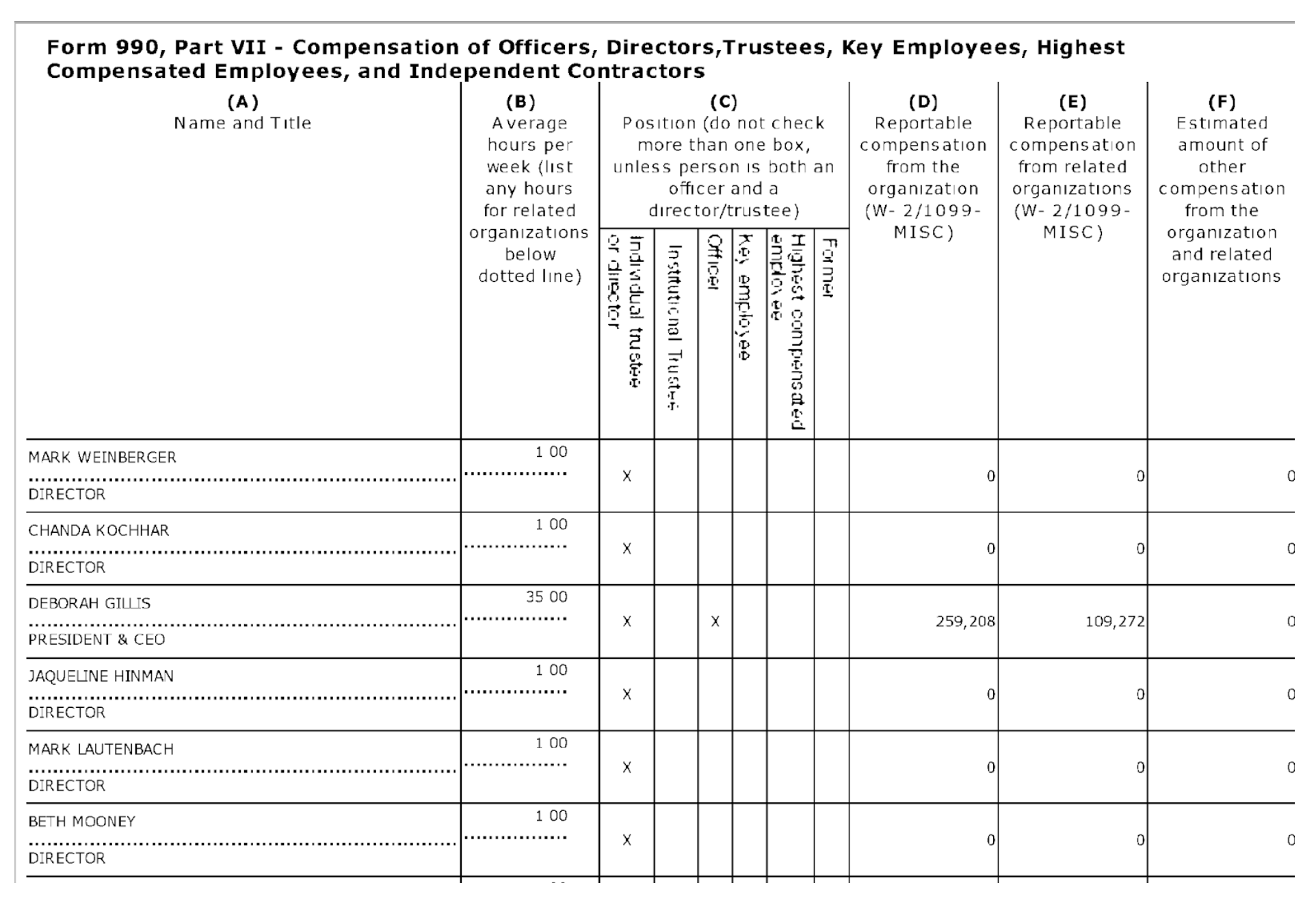

Catalyst’s Section VII is five pages long and lists 50 individuals (see the fourth of five pages, below). Thirty-nine of these individuals work one hour per week for the organization (column B), and receive no compensation (columns D – F). The other 11 of these individuals work 35 hours per week, and receive between $130,106 and $259,208 in primary compensation (column D), and between $24,571 and $109,272 in compensation from related organizations (columns E and F). Note that the title of Part VII says that this chart lists “Key Employees, Highest Compensated Employees, and Independent Contractors.” Recall from Part I that Catalyst has 107 employees, so most of them are not listed in this table.

Catalyst

Catalyst

It is evident that whereas the World Clown Association is run by an uncompensated board of directors, Catalyst has both a board of directors and a well-compensated staff.

What can be done with all this information when evaluating a nonprofit’s credibility? First, each of the names listed in this table of board members and employees is searchable. There probably is a fair bit we can learn about the credibility of an organization by evaluating the credibility of its board members and key employees. So, Google away.

Second, the people listed in this table often are the sources quoted in news articles and other reports. The Hollywood Reporter article quotes Pam Moody, president of World Clown Association, who is listed as vice-president in the form (with time, vice-presidents sometimes rise to become presidents, so this discrepancy in titles is understandable). Like others listed in the table, she receives no compensation from the World Clown Association. Brandee Stellings, a Catalyst vice president quoted in the USA Today article, is a full-time employee who earned almost $175,000 in 2015. Does knowing this information affect how we evaluate the credibility of these individuals and the quotes they gave?

On the one hand, Stellings’ salary might suggest that she is not super credible because she has a lot to lose if the organization doesn’t perform well. This could mean that what she says is always going to “toe the line” for the organization. Alternately, her high salary might suggest that she is super-knowledgeable and qualified to speak on the issues that are important to Catalyst. What about Pam Moody’s credibility? Is she super-credible because she a passionate, non-paid advocate of the clowning profession, or is she not very credible because she doesn’t make a salary from the organization (like everyone else associated with this group)? All of these arguments could be appropriate.

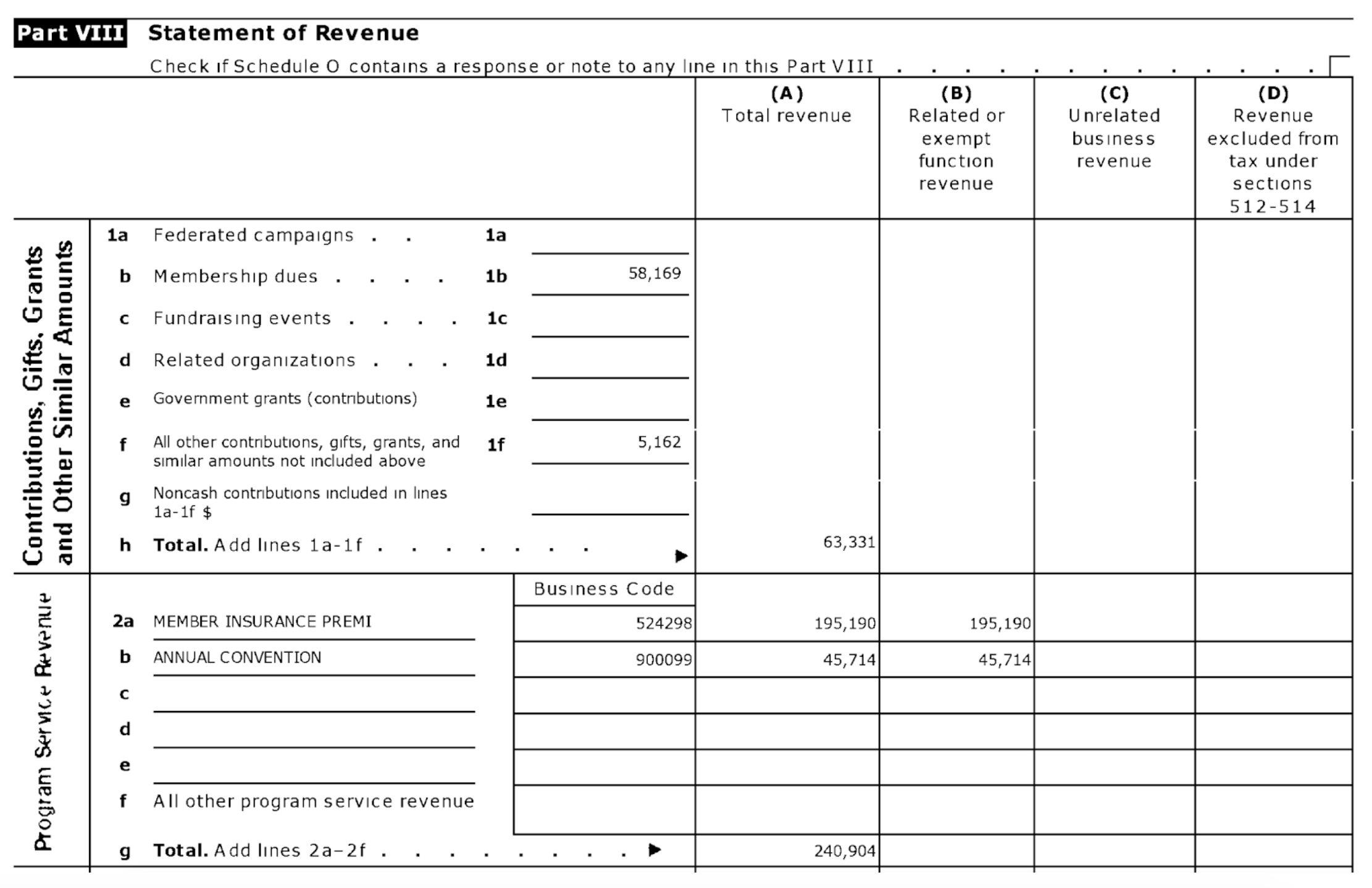

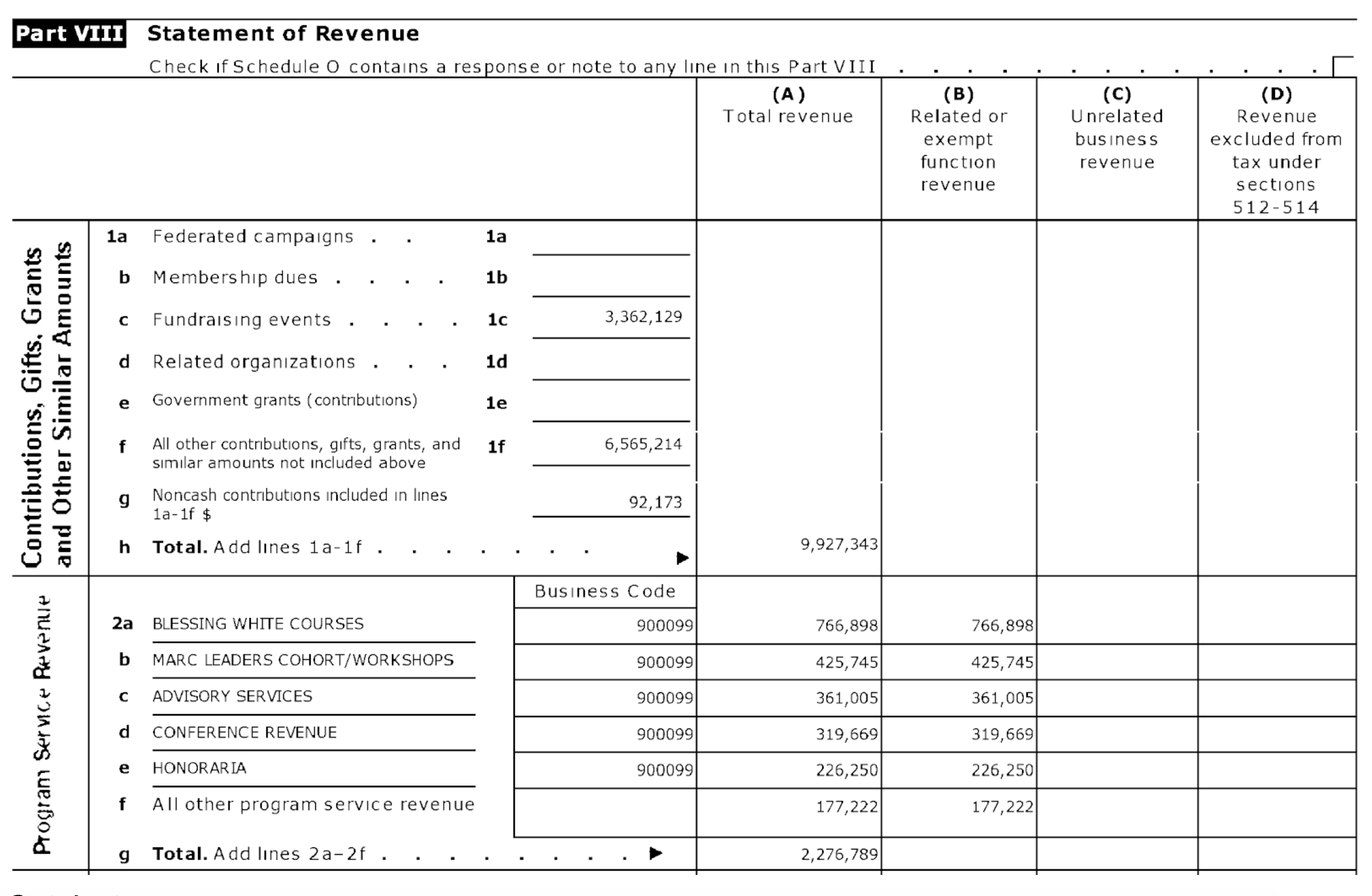

Part VIII: Revenue details

The last two sections of Form 990 that are worth considering are Parts VIII and IX, which are labeled Statement of Revenue and Statement of Functional Expenses, respectively. These sections provide more in-depth information about how these organizations generate and spend money. They provide detailed explanations of the financial summary we read on the first page of the form.

World Clown Association

World Clown Association

World Clown Association’s form shows that about a quarter of its revenue comes from membership dues (line 1b), that is, from individual clowns paying the organization to be its members. Insurance premiums from these member clowns bring in nearly half of the organization’s revenue (line 2a). The annual convention brings in almost the last quarter of the revenue (line 2b). That’s a pretty straightforward breakdown of this organization’s revenues.

Catalyst

Catalyst

Catalyst’s form shows that unlike the World Clown Association, Catalyst is not a member organization. We know this because it generates no revenue from membership dues (line 1b). Instead, it holds fundraising events (line 1c), and more importantly, it receives contributions, gifts, and non-governmental grants (line 1f). Moreover, a number of its programs generate revenue, including courses, workshops, and consulting services it offers. It also organizes a conference (line 2d), and it charges for speaker services (i.e., honoraria, line 2e).

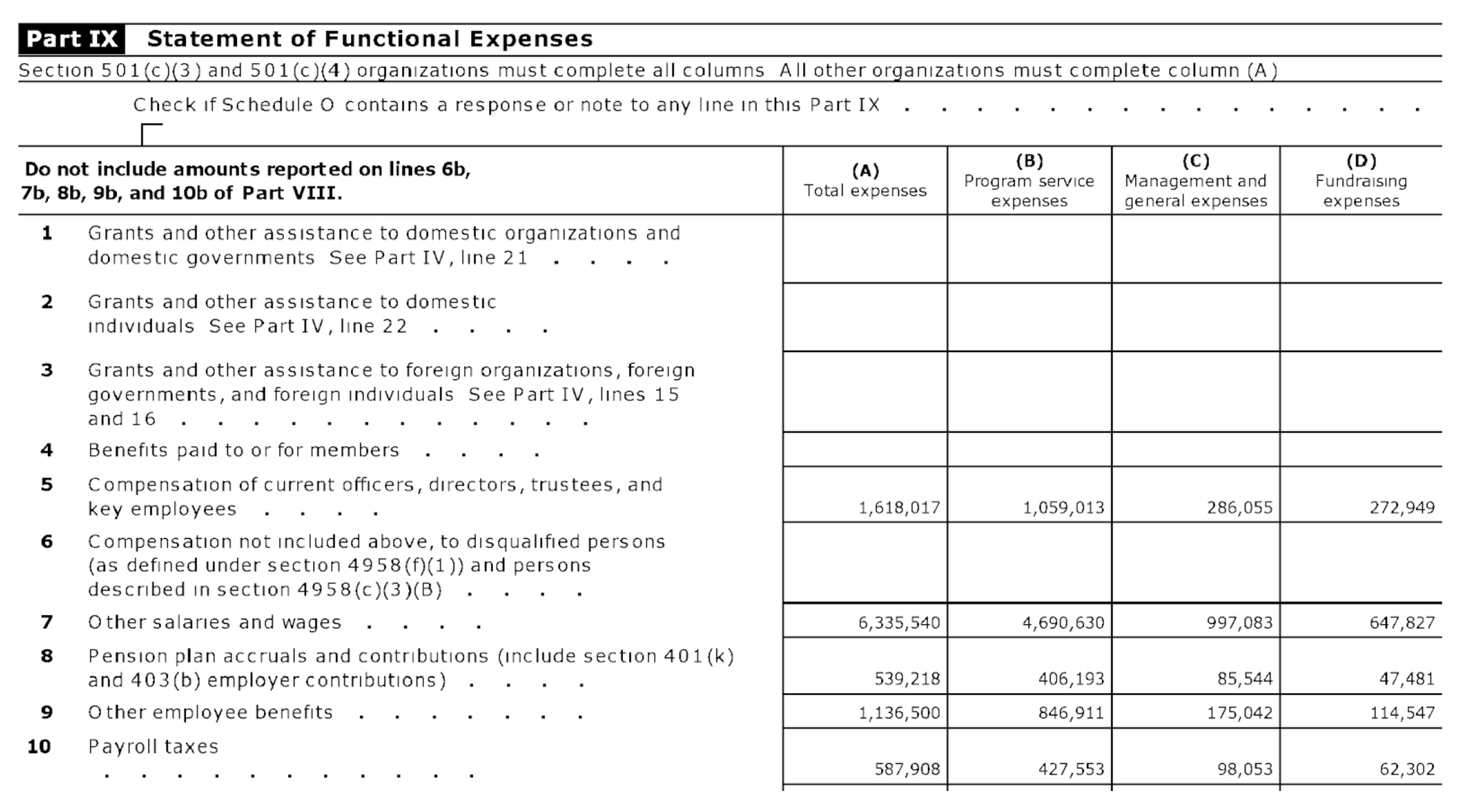

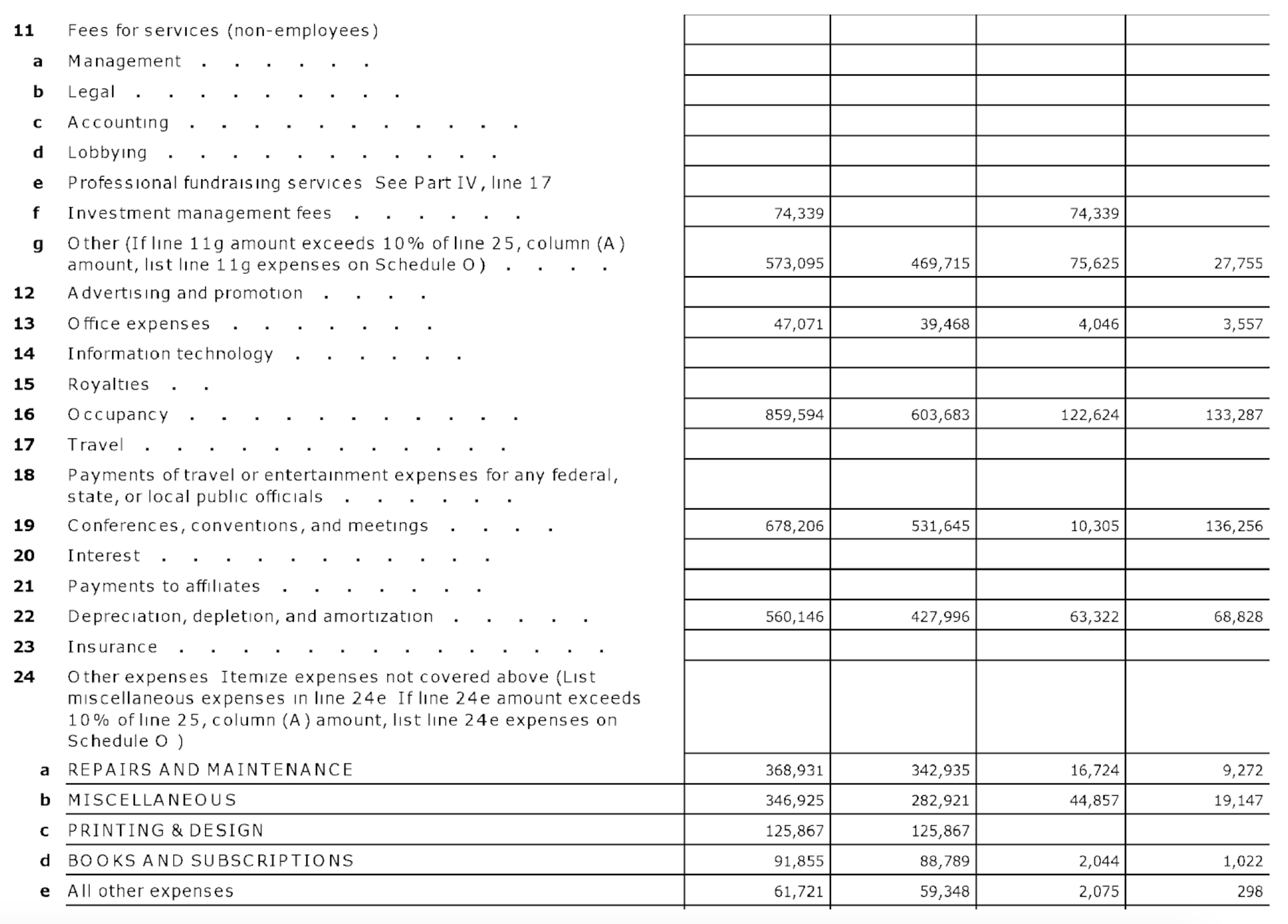

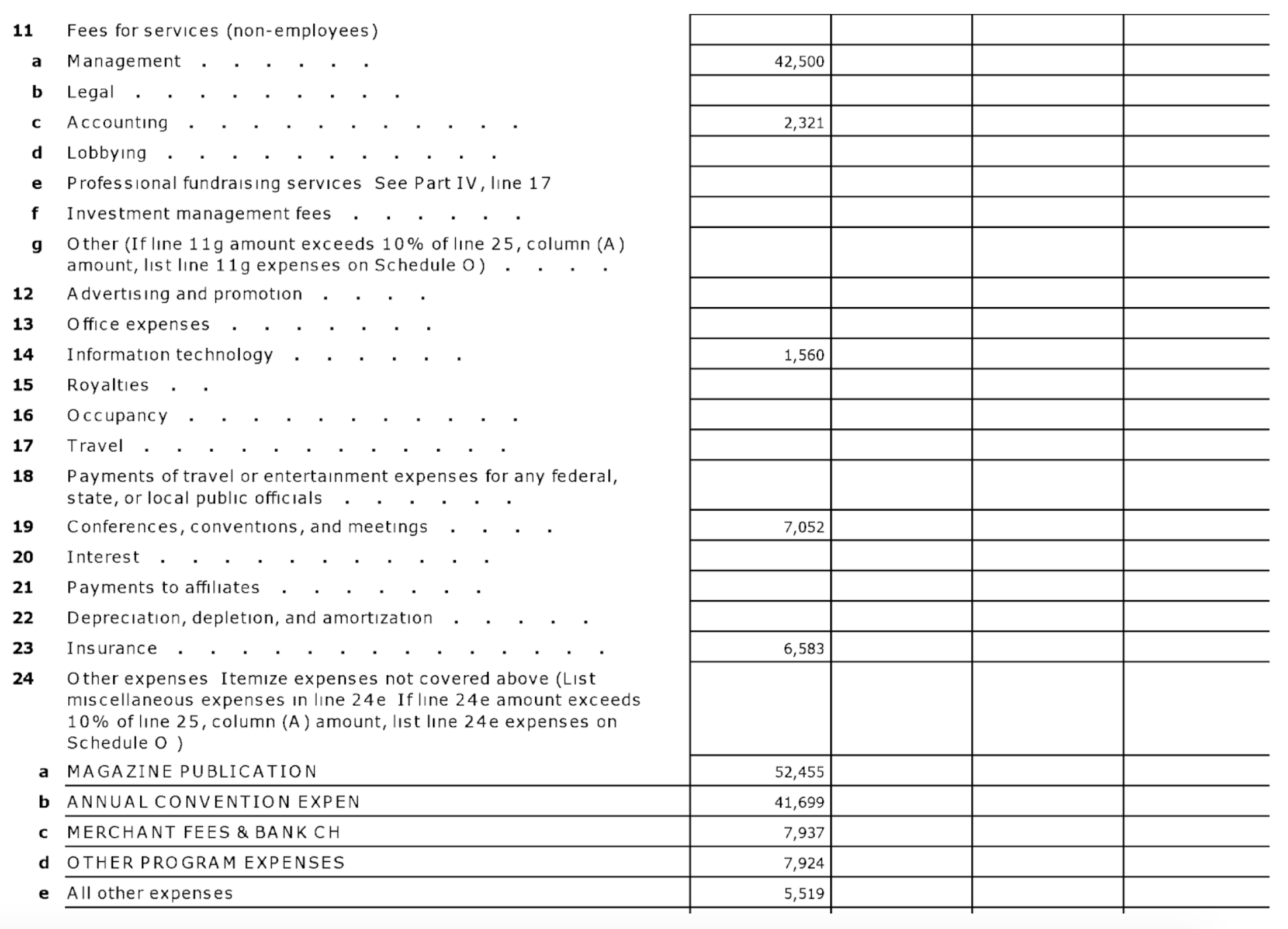

Part IX: Expense details

Catalyst

On the expenses side, one thing we wondered earlier about Catalyst was how it managed to spend 73 percent of its expenses on salaries. The top part of Part IX gives us some clues. While column A lists the total spent on salaries, pension plan contributions, and other benefits, columns B, C, and D break down these totals into expenses that support programs, management, and fundraising. Column B suggests that most of Catalyst’s salaries go toward supporting its programs. If these numbers were more skewed toward management (column C) or fundraising (column D), we would have some evidence that the organization is spending money on its key personnel and generating more revenue, rather than supporting the programs it claims to run.

Catalyst

The bottom of Part IX lists several other categories of expenses that the organization incurred, from lobbying (line 11d), to investment management (line 11f), advertising and promotion (line 12), and repairs and maintenance (line 24, other).

Reading these numbers can give us a good sense of how wisely an organization spends its funds. If the number in the advertising and promotion line is exorbitant, we could argue that the organization cares more about its public image than the programs it claims to support. This could undermine its credibility.

One large number in the Catalyst document is its occupancy figure (line 16), or the rent it pays for its office space. This figure is $859,594, or $71,633 per month. With 107 employees, this comes out to about $670 per month per employee. We all know that New York rents are expensive, and the total rent constitutes only 6 percent of the organization’s total expenses. Still, it’s worth considering whether the rent, in addition to the high salaries it pays its key employees, affects the organization’s credibility.

World Clown Association

World Clown Association

World Clown Association’s expenses include management (line 11a), which comprises about 12 percent of its total expenses. This suggests that the organization pays another company or organization (or an individual) to run its day-to-day operations. While the member volunteers listed in Section VII do some of the organization’s work, a professional manager or managers is charged with making the organization function. That’s not an exorbitant cost, especially compared to Catalyst’s 73 percent spent on salaries. And unlike Catalyst, World Clown Association pays no rent.

Comparing these two organizations’ numbers gives us a sense of the diversity of nonprofit structures, and the various costs that contribute to an organization’s overhead, that is, what it spends on itself. While some organizations like Charity Navigator provide evaluations of nonprofits’ program expenditures, you now know where such evaluations come from, and you can conduct them on your own using the figures listed in a nonprofit’s Form 990.

In sum, an organization’s Form 990 provides the journalist or strat comm professional a wealth of unvarnished information about a nonprofit organization that potentially can be used to evaluate the credibility of the organization, and help determine its appropriateness as an information source.

Peer Tutorial: How to Access and Read Form 990

In this video, Julia Barger and Bella Carollo (JOUR 302, spring 2019) demonstrate how to access Form 990 using Guidestar, and how to read the form’s main sections.

A Practitioner’s View

Susan Henderson

B.S., KU Journalism, 1995

Director of Marketing & Communications

Wholesale & Specialty Insurance Association (WSIA)

As the communications professional for an insurance trade association, I am frequently called upon as a source of information on behalf of our members, who work in a complex niche of the insurance industry.

Reporters often don’t fully understand the nuances of that market, but I can provide them with industry research, trends and demographics, and I can also quickly facilitate interviews with professionals who are experts on specific topics. Writers are always working under deadline, so my goal is to help them gather credible information that puts the association, our members and the media in the best position to tell the story and creates a win for all of us.

To ensure that we are credible and have current information, WSIA commissions research on the industry, gathers information from our members, and shares research with other industry trade associations. That broad source of facts helps me be a trustworthy source for media, but it also underscores the importance of working with trade associations for research; I do it, too.

While our members are experts in certain facets of insurance, we regularly collaborate with related associations whose members’ interests intersect with ours. Those partner associations make my job easier as the experts in their arenas, just like I do for media. As we work on legislative and regulatory issues of interest to our collective members, where we essentially become the storytellers with elected officials, those nonprofit partners as sources of information are key to our success.

Activity 1: Nonprofit Categories

Identify an issue to cover in an article or a strategic communications report. Find one or more organizations in each of the following categories that may serve as sources for this article or report: trade associations, professional societies, advocacy organizations, foundations.

Activity 2: Spokesperson Contact Info

At each of the organizations you identified above, find the name and contact information of an individual you can contact, who might serve as a source for the article or report on the issue you identified.

Activity 3: Form 990

Download the most recent Form 990 for one of the organizations you identified, and articulate 2-3 credibility arguments about this organization using evidence gleaned from this form.