6 Licensing Published Work

Karna Younger

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand the basics of copyright.

- Understand the basics of open access and openly licensed materials.

- Describe the benefits and disadvantages of licensing your published work under a Creative Commons license or to copyright it.

Getting Licensed

In this class and your future career you will be a creator of information. As a creator, you should be aware of licensing or who owns your creation and who is allowed to use it.

Throughout this text, we have discussed licensing in terms of open and closed licensing. This topic is far more complex, as the careers of many, many attorneys will attest. Regardless of the legal intricacies, we will continue to adhere to this loose binary in this chapter.

Closed

What we consider closed licensing is probably the type of publication licensing that you are most familiar: copyright. The definition of copyright varies from country to country. In the United States, copyright is defined by the U.S. Copyright Office as follows:

A form of protection provided by the laws of the United States for “original works of authorship”, including literary, dramatic, musical, architectural, cartographic, choreographic, pantomimic, pictorial, graphic, sculptural, and audiovisual creations. ‘Copyright’ literally means the right to copy but has come to mean that body of exclusive rights granted by law to copyright owners for protection of their work. Copyright protection does not extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, title, principle, or discovery. Similarly, names, titles, short phrases, slogans, familiar symbols, mere variations of typographic ornamentation, lettering, coloring, and listings of contents or ingredients are not subject to copyright.

So many words. Let’s break this down in the context of this class.

Essentially, when someone writes or creates something original, their tangible product is automatically covered under copyright. This means that the creator has the right to sell or profit from their creation and limit other people’s use of their work. Copyright allows creators to control how their work is used, and to profit from their labor.

Say, for instance, that a scholar publishes an article in a copyrighted, or closed, journal. You cannot make copies of the article and hand it out as party favors. You cannot reproduce the article or take huge chunks of it and publish them as part of your writing. This is because the author and publisher of the article has the right to restrict your use of the article. The author wants to be given credit for all of their work (via citations), and the publishing company wants to make money from selling access to the journal.

Copyright owners protect their rights in many ways. For example, you may recall that when you use the library’s databases while off campus, you have to log in with your university ID and password. This is because your library signs contracts with copyright owners, that is, publishing and database companies. The library promises that it will share copyrighted articles from those databases only with people affiliated with the university, such as faculty, students and staff. If the library breaks its end of the bargain, the publishing and database companies will immediately cut off the entire university’s access to their resources.

On a smaller scale, if you step on someone’s copyright in your own work, you may get a strongly worded cease-and-desist email from an attorney. To this you might take down the copyrighted work, reply with an apology and move on with your life. But if you take your violation too far, you may face legal action.

If you are still confused about copyright, watch this short video created by a leading copyright expert, or visit the the U.S. Copyright Office.

When you start a job, you should discuss copyright with your employer. Chances are that your work will be considered a work-for-hire and your employer will own the copyright as a condition of your employment.

Open

The term open is really broad. If a work is open, then anyone can freely access the information and use it without the author’s permission. This means there aren’t any paywalls and you can freely access the information. This does not necessarily mean, though, that you no longer have to cite the information. In most cases, you still have to give credit where credit is due. To help you better understand, let’s delve a bit deeper into two categories of open: public domain or openly licensed.

Public Domain

The public domain is not a specific place, as the U.S. Copyright Office likes to remind us. Rather, the name reflects the owners of the work: The public. This means that public domain work is not the property of a single person but of everyone because it is not under copyright.

A work becomes public domain in two ways. First, the copyright on the work may have expired. Generally speaking, copyright is granted for the life of the author plus 70 years. But if a work was made for hire, or if its author is anonymous, the copyright lasts 95 years. So in 2020, works published in this way on or before 1925 will become public domain. There are several exceptions and to these general rules. They are all discussed in this guide from the U.S. Copyright Office.

You can use this interactive copyright slider to determine if a work you’re considering is public domain.

Second, a work may be born as a public domain work. The classic example of this is government information. Anything that the U.S. government produces that is not classified is published by the Government Publishing Office and shared either in print through federal depository libraries (the University of Kansas is one!) or, increasingly, digitally. Government information is largely open because transparency and an informed citizenry encourages a flourishing free democratic society.

Open Access

Another example of how something may be born open is if it is licensed under a Creative Commons (CC) license. This does not mean that the creative work is not copyrighted. But this type of license grants creators and consumers some workarounds to make the work more accessible. CC licensing allows creators to retain the rights to their work, and allows others to copy, distribute, edit, reuse, and remix it without needing to get permission or paying for it.

You can recognize CC materials by the symbol:

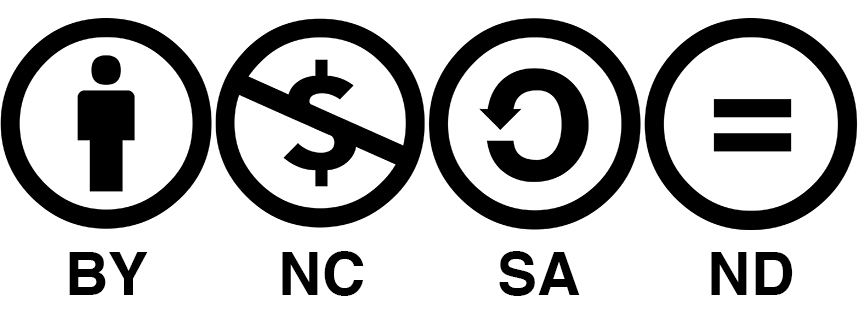

There are many different types of CC licenses, though, that dictate how an open work can be used. You will usually see one or more of these symbols next to the CC license symbol:

- BY means you want to get credit your original work. So someone must cite you or note when they’ve adapted your work.

- NC dictates that others cannot commercialize or profit from your work. So a textbook publisher cannot take this textbook, adapt and publish it to make money. This does not prevent you from profiting financially from your work.

- SA stands for share alike, meaning if you remix or reuse my work, you have to license your work under the same license as mine.

- ND is no derivatives. This prevents anyone from adapting or remixing your work because you like your work just as it is and couldn’t imagine anyone else would feel differently.

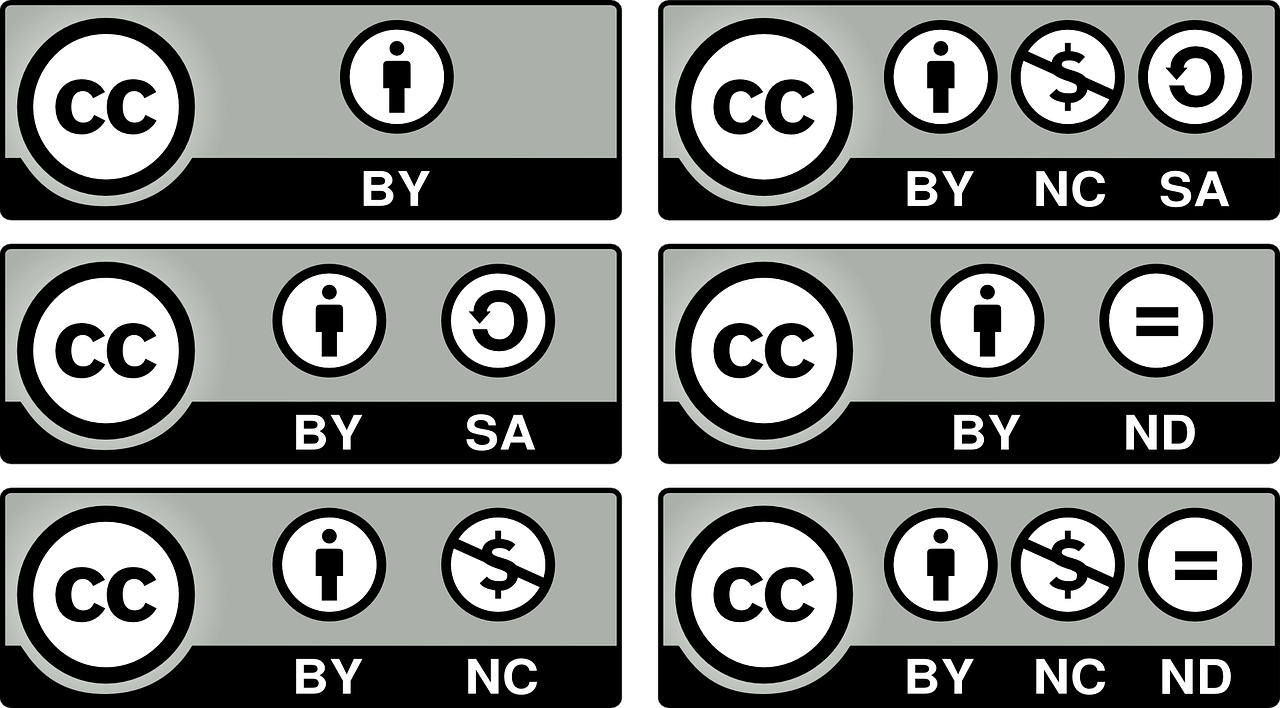

All of these licenses can be combined in a variety of different ways to ensure that your work is accessible but being used in the way you think is best. Here are a few common examples of CC license type combinations:

Sidenote: CC0 places a work in the public domain. It is the least restrictive of all licenses and allows authors to wave all of their rights.

CC and You

This class and this textbook use a CC BY NC license. We, the authors, have elected to use this license because it allows other instructors to retain a copy of the book, reuse it, revise it, remix it, and redistribute it as they wish. You can read more about this approach from David Wiley, an open education advocate.

You may be asked to create materials that can be incorporated in this textbook. Our hope is that by doing this, you and your peers will improve this textbook, and help future students learn about information and sources. If your material is included, we require it to be licensed as CC BY NC.

At the University of Kansas, you retain the copyright to any work you have created for class, according to the university’s copyright policy. If your work is chosen to be included in the textbook, your instructor will ask for your permission to openly license your material. This will not mean that you relinquish your copyright. Rather, the open license will permit users of the textbook to freely retain, reuse, revise, remix, and redistribute your work while giving you credit.

Activity 1: Into the public domain

Using Google Books or Google Scholar, try to locate one work in the public domain. Use the interactive copyright slider to confirm that the work is in the public domain.

Activity 2: Exploring Creative Commons licenses

Search the Creative Commons library for at least three items with different open licenses. Using the above charts, determine what rights are granted by the different licensed items you found. Which item has the greatest liberties and which has the least? What else can you decipher about your rights to use these found items.