4 Keep Detailed Research Notes

Karna Younger

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand the professional need for collecting and documenting evidence.

- Identify processes that journalism and strategic communication professionals use to keep track of research results.

- Design and maintain a research collection system that is usable for you and your research collaborators.

Research Notes Back Up Your Credibility

Think back to the Stephen Glass scandal discussed in the first chapter. Glass’s notebook was at the center of the investigation into his fabrications. Glass got away with publishing made-up information because he falsified his reporting notes before submitting them to the magazine’s fact-checkers, and then convinced the fact-checkers not to interrogate these notes. He requested, for instance, that his “very nervous” sources not be contacted, and created fake websites to make it appear as though he properly researched his articles. Glass cracked after Forbes Digital Tool questioned his article about a teen hacker. Glass forfeited his career because he forged his research, including the notes that supported it.

In this chapter, we discuss how your research notes will factor into the workflow, particularly the fact-checking process, of increasingly transparent news and marketing organizations. By the end, you will understand why tracking your research is important for your professional reputation and for your personal sanity.

The Problem: Credibility and Public Opinion

Journalists and other communications professionals get a bad rap. Even though large majorities of surveyed Americans have “at least some trust” in the reporting of professional news outlets, Columbia Journalism Review (CJR) found in 2019 that the media was the least trusted institution in the country. The same study revealed that 60 percent of Americans believe that reporters get paid by their sources at least some of the time while 41 percent are less likely to believe a story is true if it is using anonymous sources.

Such lack of trust is causing 38 percent of surveyed Americans to avoid the news altogether, according to the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. To combat audience drop, the media must garner the skeptical reader’s trust and maintain its credibility.

News consumers take a number of factors into account when judging the credibility of news sources, according to Pew. Readers consider the credibility of the sources that are cited, credibility of the news brand, and their “gut instinct.” If someone sends them a news article, they also factor into their decision-making process the trustworthiness of the person who shared the news with them.

As a communications professional, you only have so much control over “gut instincts” and your readers’ Facebook friends. But you can strengthen people’s faith in your sources and brand by elevating the quality and transparency of your research.

Solution: Fact-Checking Your Research and Notes

Having well-organized notes to submit to fact-checkers is key to establishing your and your employer’s credibility.

Fact-checking has been used to stifle deliberate fakers, like Glass, for about a century. Time magazine instituted one of the nation’s first fact-checking processes and, later, fact-checking departments to support muckraking journalists who used facts to take down corrupt politicians and institutions.

Today, news outlets seeking to regain the public’s trust are striving to be more transparent by publicizing their fact-checking and research processes.

Peter Canby, senior editor and head of The New Yorker’s fact-checking department, provides a good overview of the fact-checking process he oversees. This process starts with the writer, who must submit the notes, tapes, transcripts, phone numbers, web addresses, books, magazines, and anything else that he or she consulted during the writing of an article. Recreating the research process can be tedious because fact-checkers assume that they know nothing about the story’s topic.

Fact-checkers cross-reference the writer’s facts, notes and sources with other authoritative sources, such as scientists. They either verify that the writer’s research is accurate, or challenge the writer to rewrite or provide better support. Checkers at The New Yorker also call (not email) everyone who was interviewed to verify the accuracy of quotes.

Fact-checkers are particularly vocal about their penchant for grilling reporters about their notes. For instance, Canaby once spent months digging through one writer’s 25 file cabinets of notes to fact-check a piece. Similarly, a This American Life fact-checker made it a practice to “interrogate the living hell out of every single utterance of fact,” before the seven-hour podcast S-Town was released and downloaded tens of millions of times. In one instance, the fact-checker cross-examined the host’s script against interview notes, transcripts, photos, interviewees, and independent expert testimony, just to find out what kind of glue an interviewee mentioned in an off-hand comment. Was it a shellac or was it an epoxy? The host couldn’t remember what the interviewee said and the interview audio was patchy.

This American Life couldn’t say someone shellacked something if they used an epoxy, even if the interviewee was cool with it. The podcast staff felt that they could have been easily challenged by a knowing listener, so they had to get it right to avoid publishing a correction. The host’s scrupulous research methods eventually paid off when the fact-checker found a picture of the interviewee standing next to a particular can of glue.

At publications such as Time, the involvement of lawyers in the fact-checking process is a preventive measure against libel lawsuits and other legal problems. In the mid-1990s, Time and Newsweek asked their fact-checkers to take on additional reporting and writing duties. Almost immediately Newsweek was hit with a scandal. Without full-time fact-checkers, the magazine mistakenly told its readers that it was OK for 5-month-old infants to consume carrots and zwieback (twice-baked pieces of bread that serve as rusks or crackers). Hoping to avoid instigating choking incidents and accompanying lawsuits, Newsweek recalled and reprinted its issue, and published a retraction advising that infants stick to pureed solids.

In a recent example of fact-checking work at established news organizations, The Washington Post reported on its investigation of a woman’s false sexual assault accusations against the 2017 Alabama U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore. The Post’s reporter Stephanie McCrummen arranged a meeting with the purported accuser in a public place. McCrummen went into the interview having done some fact checking into the woman’s identity and background. As the interview went on, McCrummen presented evidence of this work to her interviewee and asked her to comment. This included a printout of the interviewee’s Go Fund Me webpage in which she disclosed her political motives. This all happened while McCrummen’s camera and recorder captured the conversation. McCrummen also took detailed notes and asked the interviewee to repeat herself multiple times to make sure she was aware that the conversation was being documented.

In all, the Post’s exposure of the purported Roy Moore accuser illustrates the importance of a thorough, well-documented, and transparent journalistic research process. McCrummen’s interview was recorded in the following video.

In addition to fact-checkers, a copy editor often double-checks each individual fact in a news article. For opinion pieces, the copy editor calculates whether or not all the facts add up and the writer’s argument is accurate. Before they publish anything, reputable news organizations provide what Ta-Nehisi Coates called “a dam against you embarrassing yourself” or “being so arrogant that [you] don’t even realize you’ve embarrassed yourself.”

Your memory likely can’t hold all the details of your research process. When a fact-checker or an editor requests information about the facts or sources you cite in a report, your research notes need to back you up. Where did you find this piece of information? How did you search for it? Who told you about this fact? Did you use your source’s words accurately? Keeping detailed notes during the research process pays off in the long run.

Practice: Transparency in Reporting and Advertising

If news consumers were more aware of the in-depth fact-checking that goes on at news outlets, would they put more trust in journalists and the news? Maybe journalism’s credibility crisis can be solved by having more transparency about journalistic research and fact-checking practices?

There seems to be a growing agreement that news organizations should be more open about their research and fact-checking. At the 2017 Poynter Ethics Summit, a number of the nation’s leading journalists, including The Post’s executive editor Martin Baron, pledged to be more transparent about their research process regarding their research processes after his newspaper published evidence of the interaction between The Post’s reporter and the Roy Moore accuser discussed earlier in this chapter.

The need to document research extends to the advertising industry. Advertisers adhere to self-imposed standards about researching and validating facts that appear in the advertisements they publish and air. Advertising companies are held to the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) Policy Statement on Deception. This FTC policy demands that advertisers substantiate all claims made explicitly or implicitly in their advertisements. This is meant to ensure that advertisers do not mislead the public in a way that could cause harm. For instance, advertisers can’t promise that orange juice is a healing elixir unless they document research from scientists and health professionals that substantiates this claim.

This means that if you are planning a career in advertising, you too will need to substantiate your claims by keeping track of and being transparent about your research. Your manager and the FTC will hold you accountable for every element of your advertisement, from the name of the product to the fine print, and for how the whole package adds up to a consumer’s “net impression” of a product.

In all, regardless of the profession you pursue after college, documenting your research will pay off in the long run.

Application: How to Create a Note-Taking System

To make sure that your research eventually can be verified, you should get in the habit of keeping all of your research ideas, from new ideas to project drafts. Doing so will allow you to retrace your steps and allow others, like fact-checkers or managers, to follow your tracks. You can think of your notebook as the tool that will help you transition from interviewing and researching to actually writing or creating, to getting published. There are three ways you could document your work:

Reporter’s notebook

A notebook doesn’t have to be a pad of paper, but you should track all elements of your research and sources from start to finish in a central location. This is key to being able to recall and recount what you did. Some suggested tips for your notes:

- Ideas. Write them down so that you can develop them. For example, “What tools are journalists using to make their work more transparent to news consumers?”

- Keywords. Turn your ideas into keywords to use when searching. Make lists or mind maps of broader and more specific terms. Keep track of when and where you use the keywords or phrases to replicate your successful searches. For example, “journalism, transparency, and ‘digital tools.’”

- Source notes. Once you have found, read, or talked to a source, you should document it.

- Write a summary (2-3 sentences) of the source to give yourself a quick glance at why the source is important to your research.

- Make careful notes of important statements. Be certain “direct quotes” are “properly marked” to make it clear when you are, or are not, paraphrasing your source.

- Multimedia formats. Don’t forget that your notebook may include pictures, screen captures, videos, or audio of sources and information. (Remember: Always get someone’s consent before recording them, as The Washington Post did in the above example.)

- Tools

- Pad and paper

- Google Drive

- Evernote

- Trello

- Mind map tool

- Word processing tools provided through your university, such as KU’s Microsoft myCommunity (Students have access to KU’s myCommunity as long as they are affiliated with KU. They lose access to these files once they graduate.)

Scrapbook

While you are backgrounding your topic, you should save the sources you discover so that you can locate and properly cite them while you are writing. The tools listed below will allow you to bookmark and save websites and other sources in one location.

- Tools

Data Management

Data management sounds like it might involve lots of numbers. But in reality it just means that you need to know how to consistently and properly name and store your stuff so that you and those pesky fact-checkers can easily find it. Jamene Brooks-Kiefer, KU’s data librarian, recommends the following to ensure that you are kind to your future self.

- File naming conventions

- Rules

- Keep it short (fewer than 25 characters)

- No spaces. Use_underscore_or-dashes-orNoSpaces_instead

- Don’t use special characters (bad = [$pecia|F!le\}

- Put the date at the beginning or end of the file name, if the date is important.

- YYYYMMDD or YYYY-MM-DD

- Use leading 0s for numbers (ex. SpecialFile01, SpecialFile02). This is useful if you are saving different versions of a draft.

- Rules

- Example file naming structure:

- Transparency_Journalism (folder)

- Transparency_Interviews

- GumpForrest20171208

- Transparency_Research

- TaylorDan_Benefits201512

- Transparency_Writing

- Wa_Post_Feature201801

- Transparency_Interviews

- Transparency_Journalism (folder)

- Back it up. Follow the maxim, “Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe” (LOCKSS). This means that you shouldn’t rely on your hard drive to be around forever. Keep three copies of your work: one on site (like on your hard drive), and two on different storage sites (like on a couple of different clouds). Here are some free cloud storage sites:

- Google Drive

- DropBox

- Box

- Amazon Drive (5G free)

- KU’s myCommunity (One terabit of storage. Students have access to KU’s myCommunity as long as they are affiliated with KU. They lose access to these files once they graduate.)

Here is Jamene’s handy handout of tips on data management.

Peer Tutorial: Note-Taking Methods

In this video, Miranda Hein and Molly Wiskur (JOUR 302, spring 2019) demonstrate different note-taking methods.

In the next video, Olivia Reyes (JOUR 302, spring 2019) demonstrates the Cornell method of note taking.

Peer Tutorial: Using Note-Taking Apps

In the following video, Bailey Wilson (JOUR 302, fall 2019) shows how to use Evernote, an online note-taking app, to take notes.

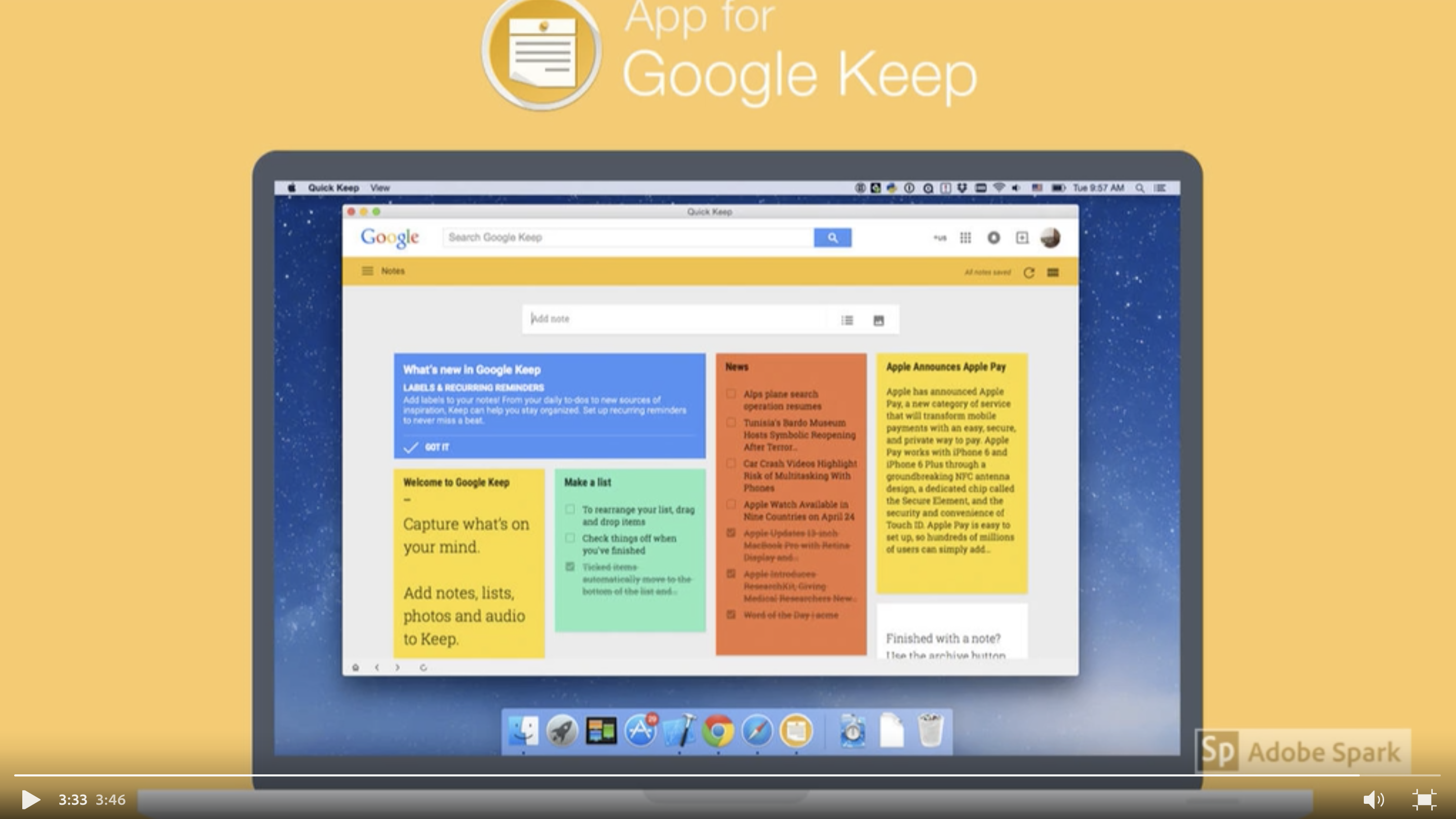

Click the image below to view a tutorial by Taylor Demoss (JOUR 302, fall 2019) on how to use Google Keep to take notes.

Activity 1: Fact-Checking Disclosures

Investigate whether or not your favorite news source posts any information about its fact-checking process online.

- If so, how accessible is the information about its fact-checking process?

- Is it easy to find, read, and understand?

- If not, is there information about it elsewhere? How do your findings impact your opinion of this news source?

Activity 2: File-Naming Conventions

Using the information about file naming conventions from the chapter, draft some sample rules for how you will name and save files related to your research projects and coursework.

Activity 3: Open Pedagogy

Explore the recording and storage tools listed in this chapter, and select tools to use for your notebook, scrapbook, and cloud storage.

- Create a tutorial of one of the tools you will use throughout the semester.

- In your tutorial discuss such aspects as its ease of use and why it integrates into your workflow.

- You may create a voice-over PowerPoint slideshow, video, or some other presentation format.