10 Persuasive Presentations

Content in this chapter is adapted from: Business Communication for Success and Speak Out, Call in: Public Speaking as Advocacy

Food for thought

We are more easily persuaded, in general, by the reasons that we ourselves discovers than by those which are given to us by others. –Pascal

For every sale you miss because you’re too enthusiastic, you will miss a hundred because you’re not enthusiastic enough. –Zig Ziglar

Getting Started

No doubt there has been a time when you wanted something from your parents, your supervisor, or your friends, and you thought about how you were going to present your request. But do you think about how often people—including people you have never met and never will meet—want something from you? When you watch television, advertisements reach out for your attention, whether you watch them or not. When you use the Internet, pop-up advertisements often appear. Living in the United States, and many parts of the world, means that you have been surrounded, even inundated, by persuasive messages. Our communication ecosystem affects how we view the world:

Consider these facts:

- By age eighteen, the average American teenager will witness on television 200,000 acts of violence, including 40,000 murders (Huston et al., 1992).

- The average person sees between four hundred and six hundred ads per day—that is forty million to fifty million by the time he or she is sixty years old. One of every eleven commercials has a direct message about beauty (Raimondo, 2010).

- By age eighteen, the average American teenager will have spent more time watching television—25,000 hours—than learning in a classroom (Ship, 2005).

- Forty percent of nine- and ten-year-old girls have tried to lose weight, according to an ongoing study funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (Body image and nutrition: Fast facts, 2009).

- Identification with television stars (for girls and boys), models (girls), or athletes (boys) positively correlated with body dissatisfaction (Hofschire & Greenberg, 2002).

- At age thirteen, 53 percent of American girls are “unhappy with their bodies.” This grows to 78 percent by the time they reach seventeen (Brumber, 1997).

- #Fitspiration and #Thinspiration images on Instagram promote decreased self-esteem and self-perceptions among college age women (Chansiri & Wongphothiphan, 2021).

- Usage of mobile dating apps relates to and self-perceived masculinity, internalized homonegativity, and body dissatisfaction among men who have sex with men (Miller & Behm-Morawitz, 2020).

The communication ecosystem has messages in narrative form, in stories, in hashtags, and in political speeches. When the CDC wanted to stop the spread of COVID-19 they put out an aggressive vaccination campaign. Your local city council often involves dialogue, and persuasive speeches, to determine zoning issues, resource allocation, and even spending priorities. You have learned many of the techniques by trial and error and through imitation. If you ever wanted the keys to your parents’ car for a special occasion, you used the principles of persuasion to reach your goal.

What Is Persuasion?

Persuasion is an act or process of presenting arguments to move, motivate, or change your audience. Aristotle taught that rhetoric, or the art of public speaking, involves the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion (Covino & Jolliffe, 1995). In the case of President Obama, he may have appealed to your sense of duty and national values. In persuading your parents to lend you the car keys, you may have asked one parent instead of the other, calculating the probable response of each parent and electing to approach the one who was more likely to adopt your position (and give you the keys). Persuasion can be implicit or explicit and can have both positive and negative effects. In this chapter we’ll discuss the importance of ethics when presenting your audience with arguments in order to motivate them to adopt your view, consider your points, or change their behavior.

Motivation is distinct from persuasion in that it involves the force, stimulus, or influence to bring about change. Persuasion is the process, and motivation is the compelling stimulus that encourages your audience to change their beliefs or behavior, to adopt your position, or to consider your arguments. Why think of yourself as fat or thin? Why should you choose to spay or neuter your pet? Messages about what is beautiful, or what is the right thing to do in terms of your pet, involve persuasion, and the motivation compels you to do something.

Another way to relate to motivation also can be drawn from the mass media. Perhaps you have watched programs like Law and Order, Cold Case, or CSI where the police detectives have many of the facts of the case, but they search for motive. They want to establish motive in the case to provide the proverbial “missing piece of the puzzle.” They want to know why someone would act in a certain manner. You’ll be asking your audience to consider your position and provide both persuasive arguments and motivation for them to contemplate. You may have heard a speech where the speaker tried to persuade you, tried to motivate you to change, and you resisted the message. Use this perspective to your advantage and consider why an audience should be motivated, and you may find the most compelling examples or points. Relying on positions like “I believe it, so you should too,” “Trust me, I know what is right,” or “It’s the right thing to do” may not be explicitly stated but may be used with limited effectiveness. Why should the audience believe, trust, or consider the position “right?” Keep an audience-centered perspective as you consider your persuasive speech to increase your effectiveness.

You may think initially that many people in your audience would naturally support your position in favor of spaying or neutering your pet. After careful consideration and audience analysis, however, you may find that people are more divergent in their views. Some audience members may already agree with your view, but others may be hostile to the idea for various reasons. Some people may be neutral on the topic and look to you to consider the salient arguments. Your audience will have a range of opinions, attitudes, and beliefs across a range from hostile to agreement.

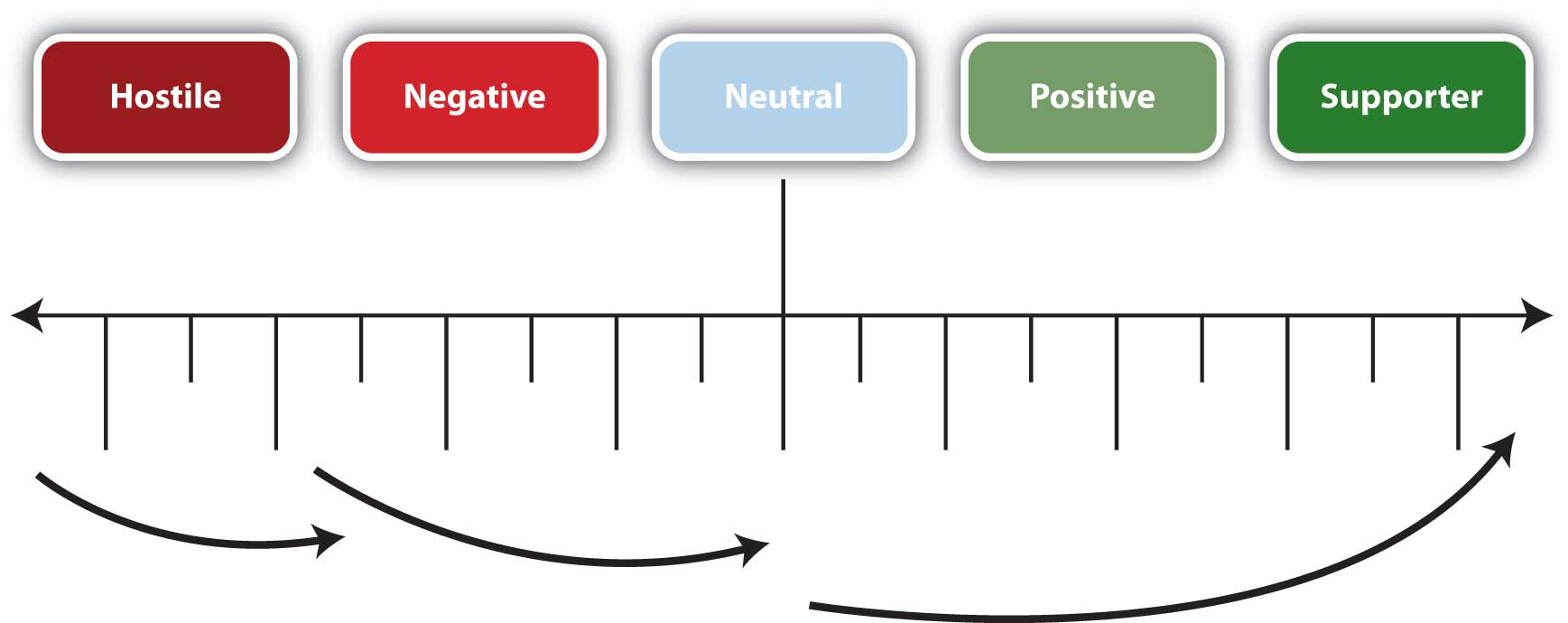

Rather than view this speech as a means to get everyone to agree with you, look at the concept of measurable gain, a system of assessing the extent to which audience members respond to a persuasive message. You may reinforce existing beliefs in the members of the audience that agree with you and do a fine job of persuasion. You may also get hostile members of the audience to consider one of your arguments, and move from a hostile position to one that is more neutral or ambivalent. The goal in each case is to move the audience members toward your position. Some change may be small but measurable, and that is considered gain. The next time a hostile audience member considers the issue, they may be more open to it. Figure 1 is a useful diagram to illustrate the concept of measurable gain.

Edward Hall also underlines this point when discussing the importance of context. The situation in which a conversation occurs provides a lot of meaning and understanding for the participants. This ability to understand motivation and context is key to good communication, and one we will examine throughout this chapter.

Meeting the Listener’s Basic Needs

This section explores why we communicate, illustrating how meeting the listener’s basic needs is central to effective communication. It’s normal for the audience to consider why you are persuading them, and there is significant support for the notion that by meeting the audience’s basic needs, whether they are a customer, colleague, or supervisor, you will more effectively persuade them to consider your position.

Not all oral presentations involve taking a position, or overt persuasion, but all focus on the inherent relationships and basic needs within the business context. Getting someone to listen to what you have to say involves a measure of persuasion, and getting that person to act on it might require considerable skill. Whether you are persuading a customer to try a new product or service, or informing a supplier that you need additional merchandise, the relationship is central to your communication. The emphasis inherent in our next two discussions is that we all share this common ground, and by understanding that we share basic needs, we can better negotiate meaning and achieve understanding.

Table 1 presents some reasons for engaging in communication. As you can see, the final item in the table indicates that we communicate in order to meet our needs.

Table 1 Reasons for Engaging in Communication

| Review | Why We Engage in Communication |

|---|---|

| Gain Information | We engage in communication to gain information. This information can involve directions to an unknown location, or a better understanding about another person through observation or self-disclosure. |

| Understand Communication Contexts | We also want to understand the context in which we communication, discerning the range between impersonal and intimate, to better anticipate how to communicate effectively in each setting. |

| Understand Our Identity | Through engaging in communication, we come to perceive ourselves, our roles, and our relationships with others. |

| Meet Our Needs | We meet our needs through communication. |

Maslow’s Hierarchy

If you have taken courses in anthropology, philosophy, psychology, or perhaps sociology in the past, you may have seen Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Figure 3). Psychologist Abraham Maslow studied with the Blackfoot Native American’s in the 1930’s and borrowed their Tipi model of understanding human development to create his hierarchy of needs (Taylor, 2019). provides seven basic categories for human needs, and arranges them in order of priority, from the most basic to the most advanced.

In this figure, we can see that we need energy, water, and air to live. Without any of these three basic elements, which meet our physiological needs (1), we cannot survive. We need to meet them before anything else, and will often sacrifice everything else to get them. Once we have what we need to live, we seek safety (2). A defensible place, protecting your supply lines for your most basic needs, could be your home. For some, however, home is a dangerous place that compromises their safety. Children and victims of domestic violence need shelter to meet this need. In order to leave a hostile living environment, people may place the well-being and safety of another over their own needs, in effect placing themselves at risk. An animal would fight for its own survival above all else, but humans can and do acts of heroism that directly contradict their own self-interest. Our own basic needs motivate us, but sometimes the basic needs of others are more important to us than our own.

We seek affection from others once we have the basics to live and feel safe from immediate danger. We look for a sense of love and belonging (3). All needs in Maslow’s model build on the foundation of the previous needs, and the third level reinforces our need to be a part of a family, community, or group. This is an important step that directly relates to business communication. If a person feels safe at your place of business, they are more likely to be open to communication. Communication is the foundation of the business relationship, and without it, you will fail. If they feel on edge, or that they might be pushed around, made to feel stupid, or even unwanted, they will leave and your business will disappear. On the other hand, if you make them feel welcome, provide multiple ways for them to learn, educate themselves, and ask questions in a safe environment, you will form relationships that transcend business and invite success.

Once we have been integrated in a group, we begin to assert our sense of self and self-respect, addressing our need for self-esteem (4). Self-esteem is essentially how we feel about ourselves. Imagine you had taken up biking, but your first task was to climb a steep hill. Afterwards you may think “biking is not for me” or feel defeated. Your feelings of self-worth tied to experiences capture different facets of your self-esteem. But, self-esteem describes the collection of several experiences which make up your feelings about your own ability and worth. Self-esteem reinforces safety and familiarity, belonging to a group or perceiving a trustworthy support system, and the freedom to make mistakes.

The top levels of Maslow’s hierarchy are called growth needs (5 – 8). Maslow discusses the next level of needs in terms of how we feel about ourselves and our ability to assert control and influence over our lives. Once we are part of a group and have begun to assert ourselves, we start to feel as if we have reached our potential and are actively making a difference in our own world. Maslow calls this self-actualization (5). Self-actualization can involve reaching your full potential, feeling accepted for who you are, and perceiving a degree of control or empowerment in your environment. It may mean the freedom to go beyond building the bird house to the tree house, and to design it yourself as an example of self-expression.

As we progress across these levels, our basic human curiosity about the world around us emerges. When we have our basic needs met, we do not need to fear losing our place in a group or access to resources. We are free to explore and play, discovering the world around us. Our need to know motivates us to grow and learn.

Maslow’s hierarchy demonstrate how our most basic needs are quite specific, and as we progress through the levels, the level of abstraction increases until ultimately we feel more comfortable engaging in more abstract and personally fulfilling needs. As we increase our degree of interconnectedness with others, we become interdependent and, at the same time, begin to express independence and individuality. As a speaker, you ought to consider where your message will appeal to the audience. If you can make it about basic needs, it might be motivational. If you can connect to growth, fulfillment, curiosity, etc. you may present a more appealing message to the audience.

Your audience will share with you a need for control. You can help meet this need by constructing your speech with an effective introduction, references to points you’ve discussed, and a clear conclusion. The introduction will set up audience expectations of points you will consider, and allow the audience to see briefly what is coming. Your internal summaries, signposts, and support of your main points all serve to remind the audience what you’ve discussed and what you will discuss. Finally, your conclusion answers the inherent question, “Did the speaker actually talk about what they said they were going to talk about?” and affirms to the audience that you have fulfilled your objectives.

Speaking Ethically and Avoiding Fallacies

What comes to mind when you think of speaking to persuade? Perhaps the idea of persuasion may bring to mind propaganda and issues of manipulation, deception, intentional bias, bribery, and even coercion. Each element relates to persuasion, but in distinct ways. In a democratic society, we support free and open discussion and invite deliberation and debate when considering change. Each of these elements also has a negative connotation associated with it. Deceiving your audience, bribing a judge, or coercing people to do something against their wishes are wrong because these tactics violate our sense of fairness, freedom, and ethics.

Manipulation involves the management of facts, ideas or points of view to play upon inherent insecurities or emotional appeals to one’s own advantage. Your audience expects you to treat them with respect, and deliberately manipulating them by means of fear, guilt, duty, or a relationship is unethical. In the same way, deception involves the use of lies, partial truths, or the omission of relevant information to mislead your audience. No one likes to be lied to, or made to believe something that is not true.

As Martin Luther King Jr. stated in his advocacy of nonviolent resistance, two wrongs do not make a right. They are just two wrongs and violate the ethics that contribute to community and healthy relationships. Being ethical is intimately related to persuasion, so speakers should be concerned with ethics.

Eleven Points for Speaking Ethically

In his book Ethics in Human Communication, Richard Johannesen (1996) offers eleven points to consider when speaking to persuade. His main points reiterate many of the points across this chapter and should be kept in mind as you prepare, and present, your persuasive message.

Do NOT:

- use false, fabricated, misrepresented, distorted or irrelevant evidence to support arguments or claims.

- intentionally use unsupported, misleading, or illogical reasoning.

- represent yourself as informed or an “expert” on a subject when you are not.

- use irrelevant appeals to divert attention from the issue at hand.

- ask your audience to link your idea or proposal to emotion-laden values, motives, or goals to which it is actually not related.

- deceive your audience by concealing your real purpose, by concealing self-interest, by concealing the group you represent, or by concealing your position as an advocate of a viewpoint.

- distort, hide, or misrepresent the number, scope, intensity, or undesirable features of consequences or effects.

- use “emotional appeals” that lack a supporting basis of evidence or reasoning.

- oversimplify complex, gradation-laden situations into simplistic, two-valued, either-or, polar views or choices.

- pretend certainty where tentativeness and degrees of probability would be more accurate.

- advocate something which you yourself do not believe in.

Aristotle said the mark of a good person, well spoken was a clear command of the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion. He discussed the idea of perceiving the many points of view related to a topic, and their thoughtful consideration. While it’s important to be able to perceive the complexity of a case, you are not asked to be a lawyer defending a client.

In your speech to persuade, consider honesty and integrity as you assemble your arguments. Your audience will appreciate your thoughtful consideration of more than one view, your understanding of the complexity, and you will build your ethos, or credibility, as you present. Be careful not to stretch the facts, or assemble them only to prove yourself, and instead prove the argument on its own merits. Deception, coercion, intentional bias, manipulation and bribery have no place in your speech to persuade.

Avoiding Fallacies

Fallacies are another way of saying false logic. These rhetorical tricks deceive your audience with their style, drama, or pattern, but add little to your speech in terms of substance and can actually detract from your effectiveness. There are several techniques or “tricks” that allow the speaker to rely on style without offering substantive argument, to obscure the central message, or twist the facts to their own gain. Here we will examine the eight classical fallacies. You may note that some of them relate to the ethical cautions listed earlier in this section. Eight common fallacies are presented in Table 5. Learn to recognize these fallacies so they can’t be used against you, and so that you can avoid using them with your audience.

Table 5 Common Fallacies

| Fallacy | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Red Herring | Any diversion intended to distract attention from the main issue, particularly by relating the issue to a common fear. | It’s not just about the death penalty; it’s about the victims and their rights. You wouldn’t want to be a victim, but if you were, you’d want justice. |

| 2. Straw Man | A weak argument set up to be easily refuted, distracting attention from stronger arguments | What if we released criminals who commit murder after just a few years of rehabilitation? Think of how unsafe our streets would be then! |

| 3. Begging the Question | Claiming the truth of the very matter in question, as if it were already an obvious conclusion. | We know that they will be released and unleashed on society to repeat their crimes again and again. |

| 4. Circular Argument | The proposition is used to prove itself. Assumes the very thing it aims to prove. Related to begging the question. | Once a killer, always a killer. |

| 5. Ad Populum | Appeals to a common belief of some people, often prejudicial, and states everyone holds this belief. Also called the Bandwagon Fallacy, as people “jump on the bandwagon” of a perceived popular view. | Most people would prefer to get rid of a few “bad apples” and keep our streets safe. |

| 6. Ad Hominem | “Argument against the man” instead of against his message. Stating that someone’s argument is wrong solely because of something about the person rather than about the argument itself. | Our representative is a drunk and philanderer. How can we trust him on the issues of safety and family? |

| 7. Non Sequitur | “It does not follow.” The conclusion does not follow from the premises. They are not related. | Since the liberal antiwar demonstrations of the 1960s, we’ve seen an increase in convicts who got let off death row. |

| 8. Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc | “After this, therefore because of this,” also called a coincidental correlation. It tries to establish a cause-and-effect relationship where only a correlation exists. | Violent death rates went down once they started publicizing executions. |

Avoid false logic and make a strong case or argument for your proposition.

Organize your thoughts and practice (as a group)

Have you ever organized a garage sale? The first step, before putting up signs or pricing items, is to go through your closets and garage and create “piles” of items that you want to sell: children’s items, tools, kitchen items, furniture, trash, etc. Researchers have found that “chunking” information, that is, the way it is grouped, is vital to audience understanding, learning, and retention of information (Beighly, 1954; Bodeia et al., 2006; Daniels & Whitman, 1981).

As we listen, we have limits as to how many categories of information we can keep in mind. In public speaking, use approximately 3 categories to group your information. 2-3 main points – or groups – is safe territory, and you should avoiding having more than 5 main points for an audience to track.

So, how do you group content or find categories. Well, if you’re presenting in a team this is a social process. Start talking to each other about how you want to organize the content, who would like to say what, and how you can put it all into a logical order that will resonate with your audience. Use your research and your brainstorming tactics! As you research, look at the articles and websites you read and say, “That information relates to what I read over here” and, “That statistic fits under the idea of . . .” You are looking for similarities and patterns. Think back to the yard sale example – you would group according to customer interest and the purpose of each item. As you learn more about your topic and expand your expertise, the patterns and groups will become clearer.

Once you locate a pattern, that information can likely be grouped into your speech’s main points. Return to your central idea or thesis and determine what groups are more suitable to support your specific purpose. If you continue to find more groups, you may want to limit and narrow your topic down further.

Finally, because your audience will understand you better and perceive you as organized, you will gain more credibility as a speaker if you are organized, assuming you also have credible information and acceptable delivery (Slagell, 2013; Sharp & McClung, 1966).

Pro-Tip: Grouping Content Helps Your Writing! Yun, Costantini, and Billingsley (2012) found a side benefit to learning to be an organized public speaker: your writing skills will improve, specifically your organization and sentence structure. Working on your organization will increase your critical thinking skills all around.

A motivated sequence for speaking. One easy way to organize your ideas is as a five-step motivational checklist. Your goal as a speaking group is to:

- Get their attention

- Identify the need (i.e., Problem)

- Satisfy the need (i.e., Solution to the problem)

- Present a vision or solution

- Offer a concrete call to action.

This simple organizational pattern can help you focus on the basic elements of a persuasive message when time is short and your performance is critical.

PRACTICE!!!!

The first time you make your argument out loud should NOT be the time your public presentation. Dwyer and Davidson (2012) report that the highest ranked fear among American college students is public speaking (just above financial problems and death!) Dwyer and Davidson (2012) remind readers, “High PSA [public speaking anxiety] has been associated with poor speech preparation, poor speech decision-making and negative affect and effect in performance” (p. 100). So, what does this mean for your team? First, know that your team will be hesitant to practice in advance (which leads to poor decision-making, negative feelings, and worse performance). Second, the inverse is also true–the more you and your teammates practice, the better decisions you will make, the better you will feel, and the better your persuasive presentation. In short, you need to practice as a team if you expect to present a compelling and persuasive argument. If your team does not practice in advance you are likely to fumble the presentation, repeat content, and leave a poor impression. Practice!!! References

- Albertson, E. (2008). How to open doors with a brilliant elevator speech. New Providence, NJ: R. R. Bowker.

- Altman, I., & Taylor, D. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- American Foreign Service Manual. (1975).

- Body image and nutrition: Fast facts. (2009). Teen Health and the Media. Retrieved from http://depts.washington.edu/thmedia/view.cgi?section=bodyimage&page=fastfacts.

- Brumberg, J. J. (1997). The body project: An intimate history of American girls. New York, NY: Random House.

- Chansiri, K., & Wongphothiphan, T. (2021). The indirect effects of Instagram images on women’s self-esteem: The moderating roles of BMI and perceived weight. New Media & Society, https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211029975

- Covino, W. A., & Jolliffe, D. A. (1995). Rhetoric: Concepts, definitions, boundaries. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- DuRant, R. H. (1997). Tobacco and alcohol use behaviors portrayed in music videos: Content analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 1131–1135.

- Dwyer, K. K., & Davidson, M. M. (2012). Is public speaking really more feared than death?. Communication Research Reports, 29(2), 99-107.

- Frommer, F. (2012). How PowerPoint makes you stupid.Trans. by Holoch, G. New York, NY: The New Press.

- Hall, E. (1966). The hidden dimension. New York, NY: Doubleday.

- Hasson, U., Hendler, T., Bashat, D.B., & Malach, R. (2001) Vase or face? A neural correlates of shape-selective grouping processes in the human brain. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, Vol 13, No. 6, 744-753.

- Hofschire, L. J., & Greenberg, B. S. (2002). Media’s impact on adolescent’s body dissatisfaction. In D. Brown, J. R. Steele, & K. Walsh-Childers (Eds.), Sexual Teens, Sexual Media. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Howell, L. (2006). Give your elevator speech a lift. Bothell, WA: Publishers Network.

- Huston, A. C., et al. (1992). Big world, small screen: The role of television in American society. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Johannesen, R. (1996). Ethics in human communication (4th ed.). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

- Lauer, D. A. & Pentak, S. (2000). Design basics (5th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College Publishers.

- Maier, D., Li, J., Tucker, P., Tufte, K., & Papadimos, V. (2005). Semantics of data streams and operators. Database Theory – Icdt 2005, Proceedings,3363, 37-52

- Maslow, A. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Roe.

- Miller, B., & Behm-Morawitz, E. (2020). Investigating the cultivation of masculinity and body self-attitudes for users of mobile dating apps for men who have sex with men. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 21(2), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000221

- Raimondo, M. (2010). About-face facts on the media. About-face. Retrieved from http://www.about-face.org/r/facts/media.shtml.

- Ship, J. (2005, December). Entertain. Inspire. Empower. How to speak a teen’s language, even if you’re not one. ChangeThis. Retrieved from http://www.changethis.com/pdf/20.02.TeensLanguage.pdf.

- Taylor, S. (2019). Original influences: How the ideas of America were shaped by Native Americans. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/out-the-darkness/201903/original-influences

- Tiggemann, M., & Pickering, A. S. (1996). Role of television in adolescent women’s body: Dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 20, 199–203.

- Tufte, E. (2005) PowerPoint does rocket science–and better techniques for technical reports. Retrieved from https://www.edwardtufte.com/bboard/q-and-a-fetch-msg?msg_id=0001yB&topic_id=1

A description of the many forms of communication we engage in regularly including interpersonal conversations, mass media, and social media.

An act or process of presenting arguments to move, motivate, or change your audience.

the force, stimulus, or influence to bring about change

A system of assessing the extent to which audience members respond to a persuasive message (ranging from hostile to supporter).

The situational components of a conversation. Context involves past experiences, similarities, differences, and other information that shapes a conversation or presentation.

Food, water, air, and energy--Step 1 of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.

A defensible place, protecting your supply lines for your most basic needs, could be your home--Step 2 of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.

our need to be a part of a family, community, or group--Step 3 in Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.

The feeling of confidence in one’s own abilities or worth.

Needs for growing intellectual development, asethetic or beauty needs, and eventually actualization and transcendence (seeing yourself of something bigger than your body).

Feelings of reaching your full potential, feeling accepted for who you are, and perceiving a degree of control or empowerment in your environment.

the management of facts, ideas or points of view to play upon inherent insecurities or emotional appeals to one’s own advantage

the use of lies, partial truths, or the omission of relevant information to mislead your audience.

Rhetorical tricks deceive your audience with their style, drama, or pattern, but add little to your speech in terms of substance and can actually detract from your effectiveness.

A five step motivational process: 1) Get their attention

2) Identify the need (i.e., Problem)

3) Satisfy the need (i.e., Solution to the problem)

4) Present a vision or solution

5) Offer a concrete call to action.