13 Organizational culture

The following content comes from Organizational Behavior

Just like individuals, you can think of teams and organizations as having their own personalities, more typically known as organizational or team cultures. The opening case illustrates that Nordstrom is a retailer with the foremost value of making customers happy. At Nordstrom, when a customer is unhappy, employees are expected to identify what would make the person satisfied, and then act on it, without necessarily checking with a superior or consulting a lengthy policy book. If they do not, they receive peer pressure and may be made to feel that they let the company down. In other words, this organization seems to have successfully created a service culture. Understanding how organizational and team culture is created, communicated, and changed will help you be more effective in your organizational life.

Example: Building a Customer Service Culture: The Case of Nordstrom

Nordstrom Inc. (NYSE: JWN) is a Seattle-based department store rivaling the likes of Saks Fifth Avenue, Neiman Marcus, and Bloomingdale’s. Nordstrom is a Hall of Fame member of Fortune magazine’s “100 Best Companies to Work For” list, including being ranked 34th in 2008. Nordstrom is known for its quality apparel, upscale environment, and generous employee rewards. However, what Nordstrom is most famous for is its delivery of customer service above and beyond the norms of the retail industry. Stories about Nordstrom service abound. For example, according to one story the company confirms, in 1975 Nordstrom moved into a new location that had formerly been a tire store. A customer brought a set of tires into the store to return them. Without a word about the mix-up, the tires were accepted, and the customer was fully refunded the purchase price. In a different story, a customer tried on several pairs of shoes but failed to find the right combination of size and color. As she was about to leave, the clerk called other Nordstrom stores but could only locate the right pair at Macy’s, a nearby competitor. The clerk had Macy’s shipped the shoes to the customer’s home at Nordstrom’s expense. In a third story, a customer describes wandering into a Portland, Oregon, Nordstrom looking for an Armani tuxedo for his daughter’s wedding. The sales associate took his measurements just in case one was found. The next day, the customer got a phone call, informing him that the tux was available. When pressed, she revealed that using her connections she found one in New York, had it put on a truck destined to Chicago, and dispatched someone to meet the truck in Chicago at a rest stop. The next day she shipped the tux to the customer’s address, and the customer found that the tux had already been altered for his measurements and was ready to wear. What is even more impressive about this story is that Nordstrom does not sell Armani tuxedos.

How does Nordstrom persist in creating these stories? If you guessed that they have a large number of rules and regulations designed to emphasize quality in customer service, you’d be wrong. In fact, the company gives employees a 5½-inch by 7½-inch card as the employee handbook. On one side of the card, the company welcomes employees to Nordstrom and states that their number one goal is to provide outstanding customer service, and for this they have only one rule. On the other side of the card, the single rule is stated: “Use good judgment in all situations.” By leaving it in the hands of Nordstrom associates, the company seems to have empowered employees who deliver customer service heroics every day.

Based on information from Chatman, J. A., & Eunyoung Cha, S. (2003). Leading by leveraging culture. California Management Review, 45, 19–34; McCarthy, P. D., & Spector, R. (2005). The Nordstrom way to customer service excellence: A handbook for implementing great service in your organization. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; Pfeffer, J. (2005). Producing sustainable competitive advantage through the effective management of people. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 95–106.

Discussion Questions

- Describe Nordstrom’s organizational culture.

- Despite the low wages and long hours that are typical of retail employment, Nordstrom still has the ability to motivate its staff to exhibit exemplary customer service. How might this be explained?

- What suggestions would you give Nordstrom for maintaining and evolving the organizational culture that has contributed to its success?

- What type of organizational culture do you view as most important?

- What attributes of Nordstrom’s culture do you find most appealing?

What Is Organizational Culture?

Organizational culture refers to a system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs that show employees what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior (Chatman & Eunyoung, 2003; Kerr & Slocum, 2005). These values have a strong influence on employee behavior as well as organizational performance. In fact, the term organizational culture was made popular in the 1980s when Peters and Waterman’s best-selling book In Search of Excellence made the argument that company success could be attributed to an organizational culture that was decisive, customer-oriented, empowering, and people-oriented. Since then, organizational culture has become the subject of numerous research studies, books, and articles. However, organizational culture is still a relatively new concept. In contrast to a topic such as leadership, which has a history spanning several centuries, organizational culture is a young but fast-growing area within organizational behavior.

Geertz (1973) discussed culture as “webs of significance” that people, as symbolic creatures, have collectively spun (pp. 5-6). Pacanowsky and O’Donnell-Trujillo (1983) proposed that researchers should start focusing on the act of spinning the web. If we focus only on cultural webs, researchers cannot wholly grasp organizational culture, we miss the vital aspect of our agency and contribute to those webs.

Culture is by and large invisible to individuals. Even though it affects all employee behaviors, thinking, and behavioral patterns, individuals tend to become more aware of their organization’s culture when they have the opportunity to compare it to other organizations or teams. If you have worked in multiple organizations, you can attest to this. Maybe the first organization you worked in was a place where employees dressed formally. It was completely inappropriate to question your boss in a meeting; such behaviors would only be acceptable in private. It was important to check your e-mail at night as well as during weekends or else you would face questions on Monday about where you were and whether you were sick. Contrast this company to a second organization where employees dress more casually. You are encouraged to raise issues and question your boss or peers, even in front of clients. What is more important is not to maintain impressions but to arrive at the best solution to any problem. It is widely known that family life is very important, so it is acceptable to leave work a bit early to go to a family event. Additionally, you are not expected to do work at night or over the weekends unless there is a deadline. These two hypothetical organizations illustrate that organizations have different cultures, and culture dictates what is right and what is acceptable behavior as well as what is wrong and unacceptable.

Why Does Organizational Culture Matter?

An organization or team’s culture may be one of its strongest assets, as well as its biggest liability. In fact, it has been argued that organizations that have a rare and hard-to-imitate organizational culture benefit from it as a competitive advantage (Barney, 1986). In a survey conducted by the management consulting firm Bain & Company in 2007, worldwide business leaders identified corporate culture as important as corporate strategy for business success (Why culture can mean life or death, 2007). This comes as no surprise to many leaders of successful businesses, who are quick to attribute their company’s success to their organization’s culture.

Culture represents shared values within the organization or team and is often related to increased performance. Researchers found a relationship between organizational cultures and company performance, with respect to success indicators such as revenues, sales volume, market share, and stock prices (Kotter & Heskett, 1992; Marcoulides & Heck, 1993). At the same time, it is important to have a culture that fits with the demands of the company’s environment. To the extent shared values are proper for the company in question, company performance may benefit from culture (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987). For example, if a company is in the high-tech industry, having a culture that encourages innovativeness and adaptability will support its performance. However, if a company in the same industry has a culture characterized by stability, a high respect for tradition, and a strong preference for upholding rules and procedures, the company may suffer as a result of its culture. In other words, just as having the “right” culture may be a competitive advantage for an organization, having the “wrong” culture may lead to performance difficulties, may be responsible for organizational failure, and may act as a barrier preventing the company from changing and taking risks.

Finally, organizational culture is an effective control mechanism for dictating employee behavior. Culture is in fact a more powerful way of controlling and managing employee behaviors than organizational rules and regulations. Norms are more powerful than rules. When problems are unique, rules tend to be less helpful. Instead, creating a culture of customer service achieves the same result by encouraging employees to think like customers, knowing that the company priorities in this case are clear: Keeping the customer happy is preferable to other concerns such as saving the cost of a refund.

Levels of Organizational Culture

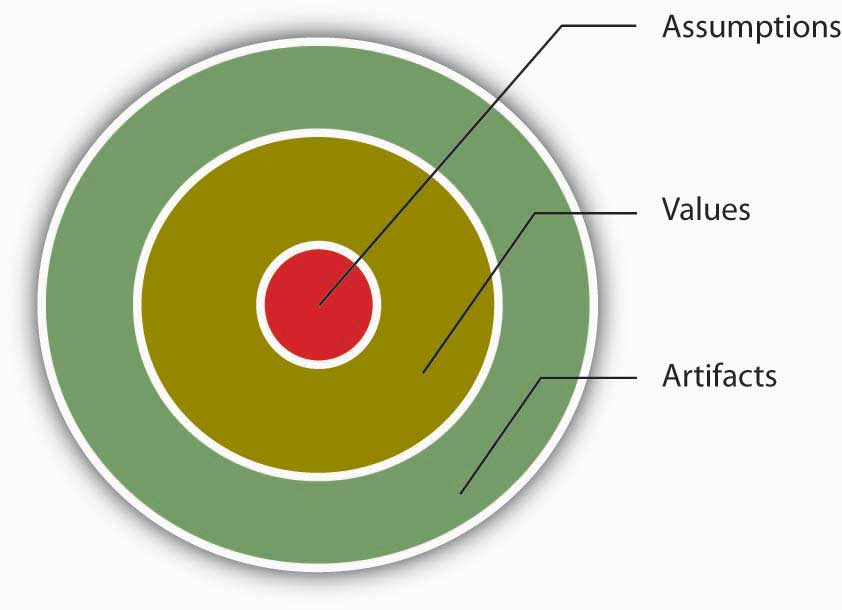

Organizational culture consists of some aspects that are relatively more visible, as well as aspects that may lie below one’s conscious awareness. Organizational culture can be thought of as consisting of three interrelated levels (Schein, 1992).

At the deepest level, below our awareness lie basic assumptions. Assumptions are taken for granted, and they reflect beliefs about human nature and reality. At the second level, values exist. Values are shared principles, standards, and goals. Finally, at the surface we have artifacts, or visible, tangible aspects of organizational culture. For example, in an organization one of the basic assumptions employees and managers share might be that happy employees benefit their organizations. This assumption could translate into values such as social equality, high-quality relationships, and having fun. The artifacts reflecting such values might be an executive “open door” policy, an office layout that includes open spaces and gathering areas equipped with pool tables, and frequent company picnics in the workplace. For example, Alcoa Inc. designed their headquarters to reflect the values of making people more visible and accessible and to promote collaboration (Stegmeier, 2008). In other words, understanding the organization’s culture may start from observing its artifacts: the physical environment, employee interactions, company policies, reward systems, and other observable characteristics. When you are interviewing for a position, observing the physical environment, how people dress, where they relax, and how they talk to others is definitely a good start to understanding the company’s culture.

However, simply looking at tangible aspects is unlikely to give a full picture of the organization. An important chunk of what makes up culture exists below one’s degree of awareness. The values and, at a deeper level, the assumptions that shape the organization’s culture can be uncovered by observing how employees interact and the choices they make, as well as by inquiring about their beliefs and perceptions regarding what is right and appropriate behavior. Finally, recent research suggests that online reviews of employers on places like Indeed.com, Glassdoor.com, and other online venues where people leave reviews of employers to serve as a vital source of information about organizational culture (Piercy & Lee, 2020).

Characteristics of Organizational Culture

Strength of Culture

A strong culture is one that is shared by organizational members (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987; Chatman & Eunyoung, 2003). In other words, if most employees in the organization show consensus regarding the values of the company, the company show signs of a strong culture. A culture’s content is more likely to affect the way employees think and behave when the culture in question is strong. For example, cultural values emphasizing customer service will lead to higher quality customer service if there is widespread agreement among employees on the importance of customer service-related values (Schneider et al., 2002).

A strong culture may act as an asset or liability for the organization, depending on the types of values that are shared. For example, imagine a company with a culture that is strongly outcome oriented. If this value system matches the organizational environment, the company outperforms its competitors. On the other hand, a strong outcome-oriented culture coupled with unethical behaviors and an obsession with quantitative performance indicators may be detrimental to an organization’s effectiveness. An extreme example of this dysfunctional type of strong culture is Enron.

A strong culture may sometimes outperform a weak culture because of the consistency of expectations. In a strong culture, members know what is expected of them, and the culture serves as an effective control mechanism on member behaviors. Research shows that strong cultures lead to more stable corporate performance in stable environments. However, in volatile environments, the advantages of culture strength disappear (Sorensen 2002).

One limitation of a strong culture is the difficulty of changing a strong culture. If an organization with widely shared beliefs decides to adopt a different set of values, unlearning the old values and learning the new ones will be a challenge, because employees will need to adopt new ways of thinking, behaving, and responding to critical events. For example, the Home Depot Inc. had a decentralized, autonomous culture where many business decisions were made using “gut feeling” while ignoring the available data. When Robert Nardelli became CEO of the company in 2000, he decided to change its culture, starting with centralizing many of the decisions that were previously left to individual stores. This initiative met with substantial resistance, and many high-level employees left during his first year. Despite getting financial results such as doubling the sales of the company, many of the changes he made were criticized. He left the company in January 2007 (Charan, 2006; Herman & Wernle, 2007).

A strong culture may also be a liability during a merger. During mergers and acquisitions, companies inevitably experience a clash of cultures, as well as a clash of structures and operating systems. Culture clash becomes more problematic if both parties have unique and strong cultures. For example, during the merger of Daimler AG with Chrysler Motors LLC to create DaimlerChrysler AG, the differing strong cultures of each company acted as a barrier to effective integration. Daimler had a strong engineering culture that was more hierarchical and emphasized routinely working long hours. Daimler employees were used to being part of an elite organization, evidenced by flying first class on all business trips. On the other hand, Chrysler had a sales culture where employees and managers were used to autonomy, working shorter hours, and adhering to budget limits that meant only the elite flew first class. The different ways of thinking and behaving in these two companies introduced a number of unanticipated problems during the integration process (Badrtalei & Bates, 2007; Bower, 2001). Differences in culture may be part of the reason that, in the end, the merger didn’t work out.

Do Organizations Have a Single Culture?

So far, we have assumed that a company has a single culture that is shared throughout the organization. However, you may have realized that this is an oversimplification. In reality there might be multiple cultures within any given organization–and teams form meaningful cultures. For example, people working on the sales floor may experience a different culture from that experienced by people working in the warehouse. A culture that emerges within different departments, branches, teams, or geographic locations is called a subculture. Subcultures may arise from the personal characteristics of employees and managers, as well as the different conditions under which work is performed. Within the same organization, marketing and manufacturing departments often have different cultures such that the marketing department may emphasize innovativeness, whereas the manufacturing department may have a shared emphasis on detail orientation.

In an interesting study, researchers uncovered five different subcultures within a single police organization. These subcultures differed depending on the level of danger involved and the type of background experience the individuals held, including “crime-fighting street professionals” who did what their job required without rigidly following protocol and “anti-military social workers” who felt that most problems could be resolved by talking to the parties involved (Jermier et al., 1991). Research has shown that employee perceptions regarding subcultures were related to employee commitment to the organization (Lok et al., 2005). Therefore, in addition to understanding the broader organization’s values, managers will need to make an effort to understand subculture values to see its impact on workforce behavior and attitudes. Moreover, as an employee, you need to understand the type of subculture in the department where you will work in addition to understanding the company’s overall culture.

Sometimes, a subculture may take the form of a counterculture, or shared values and beliefs that are in direct opposition to the values of the broader organizational culture (Kerr & Slocum, 2005). Countercultures are often shaped around a charismatic leader. For example, within a large bureaucratic organization, an enclave of innovativeness and risk taking may emerge within a single department. A counterculture may be tolerated by the organization as long as it is bringing in results and contributing positively to the effectiveness of the organization. However, its existence may be perceived as a threat to the broader organizational culture. In some cases this may lead to actions that would take away the autonomy of the managers and eliminate the counterculture.

Creating and Maintaining Organizational Culture

How Are Cultures Created?

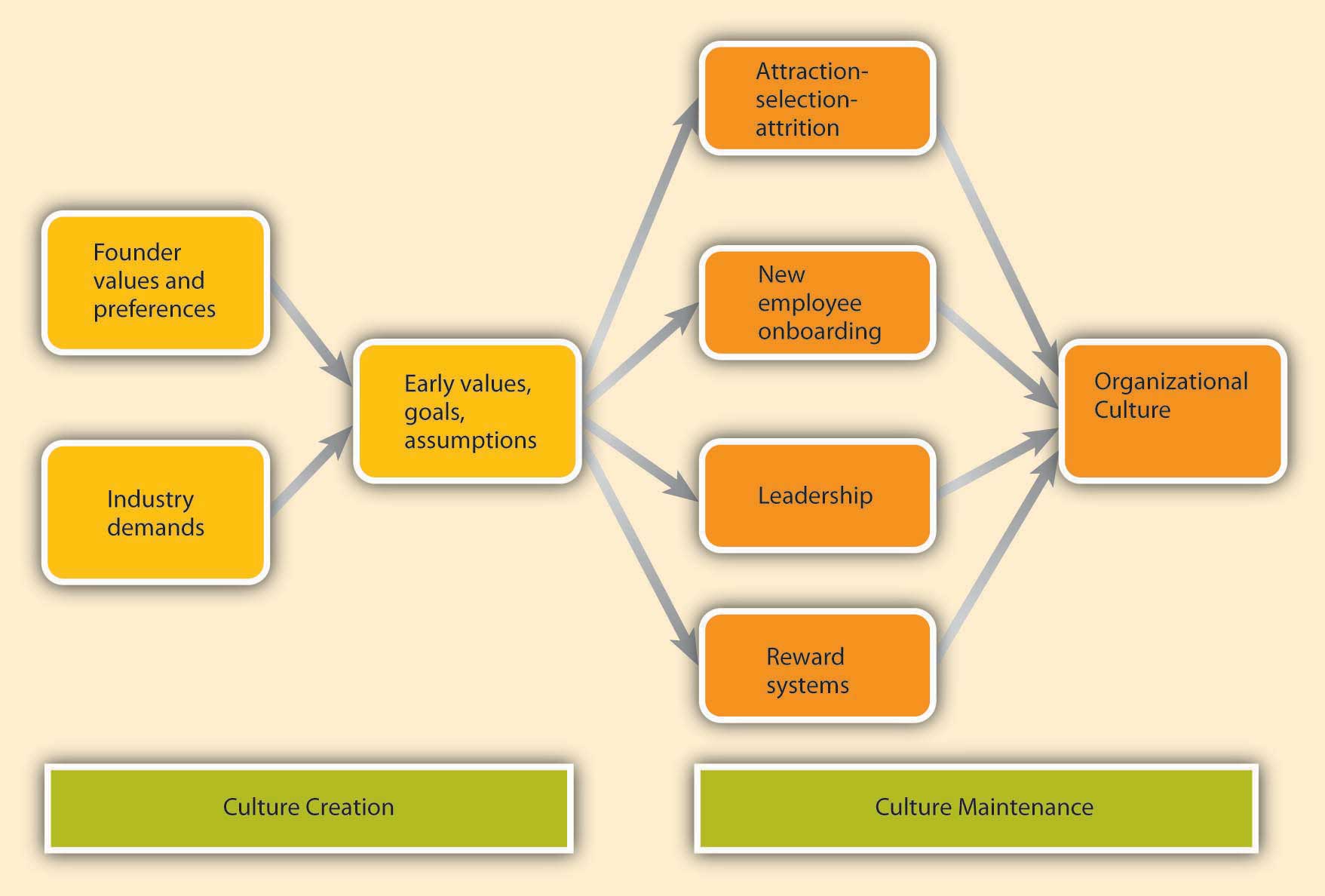

Where do cultures come from? Understanding this question is important so that you know how they can be changed. An organization or team’s culture is shaped as the organization or team faces external and internal challenges and learns how to deal with them. When the organization’s way of doing business provides a successful adaptation to environmental challenges and ensures success, those values are retained. These values and ways of doing business are taught to new members as the way to do business (Schein, 1992).

The factors that are most important in the creation of an organization’s culture include founders’ values, preferences, and industry demands.

How Are Cultures Maintained?

As a company matures, its cultural values are refined and strengthened. The early values of a company’s culture exert influence over its future values. It is possible to think of organizational culture as an organism that protects itself from external forces. Organizational culture determines what types of people are hired by an organization and what types are left out. Moreover, once new employees are hired, the company assimilates new employees and teaches them the way things are done in the organization. We call this processes onboarding.. Below examine the role of leaders and reward systems in shaping and maintaining an organization’s culture. It is important to remember two points: The process of culture creation is in fact more complex and less clean than the name implies. Additionally, the influence of each factor on culture creation is reciprocal. For example, just as leaders may influence what type of values the company has, the culture may also determine what types of behaviors leaders demonstrate.

Exploration Activity

You’ve Got a New Job! Now How Do You Get on Board?

- Gather information. Try to find as much about the company and the job as you can before your first day. After you start working, be a good observer, gather information, and read as much as you can to understand your job and the company. Examine how people are interacting, how they dress, and how they act to avoid behaviors that might indicate to others that you are a misfit.

- Manage your first impression. First impressions may endure, so make sure that you dress appropriately, are friendly, and communicate your excitement to be a part of the team. Be on your best behavior!

- Invest in relationship development. The relationships you develop with your manager and with coworkers will be essential for you to adjust to your new job. Take the time to strike up conversations with them. If there are work functions during your early days, make sure not to miss them!

- Seek feedback. Ask your manager or coworkers how well you are doing and whether you are meeting expectations. Listen to what they are telling you and also listen to what they are not saying. Then, make sure to act upon any suggestions for improvement. Be aware that after seeking feedback, you may create a negative impression if you consistently ignore the feedback you receive.

- Show success early on. In order to gain the trust of your new manager and colleagues, you may want to establish a history of success early. Volunteer for high-profile projects where you will be able to demonstrate your skills. Alternatively, volunteer for projects that may serve as learning opportunities or that may put you in touch with the key people in the company.

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Couzins, M., & Beagrie, S. (2005, March 1). How to…survive the first six months of a new job. Personnel Today, 27; Wahlgreen, E. (2002, December 5). Getting up to speed at a new job. Business Week Online. Retrieved January 29, 2009, from http://www.businessweek.com/careers/content/dec2002/ca2002123_2774.htm.

Leadership

Leaders are instrumental in creating and changing an organization’s culture. There is a direct correspondence between a leader’s style and an organization’s culture. For example, when leaders motivate employees through inspiration, corporate culture tends to be more supportive and people oriented. When leaders motivate by making rewards contingent on performance, the corporate culture tends to be more performance oriented and competitive (Sarros et al., 2002). In these and many other ways, what leaders do directly influences the cultures their organizations have.

Part of the leader’s influence over culture is through role modeling. Many studies have suggested that leader behavior, the consistency between organizational policy and leader actions, and leader role modeling determine the degree to which the organization’s culture emphasizes ethics (Driscoll & McKee, 2007). The leader’s own behaviors will signal to employees what is acceptable behavior and what is unacceptable. In an organization in which high-level managers make the effort to involve others in decision making and seek opinions of others, a team-oriented culture is more likely to evolve. By acting as role models, leaders send signals to the organization about the norms and values that are expected to guide the actions of organizational members.

Leaders also shape culture by their reactions to the actions of others around them. For example, do they praise a job well done, or do they praise a favored employee regardless of what was accomplished? How do they react when someone admits to making an honest mistake? What are their priorities? In meetings, what types of questions do they ask? Do they want to know what caused accidents so that they can be prevented, or do they seem more concerned about how much money was lost as a result of an accident? Do they seem outraged when an employee is disrespectful to a coworker, or does their reaction depend on whether they like the harasser? Through their day-to-day actions, leaders shape and maintain an organization’s culture.

Reward Systems

Finally, the company culture is shaped by the type of reward systems used in the organization, and the kinds of behaviors and outcomes it chooses to reward and punish. One relevant element of the reward system is whether the organization rewards behaviors or results. Some companies have reward systems that emphasize intangible elements of performance as well as more easily observable metrics. In these companies, supervisors and peers may evaluate an employee’s performance by assessing the person’s behaviors as well as the results. In such companies, we may expect a culture that is relatively people or team oriented, and employees act as part of a family (Kerr & Slocum, 2005). On the other hand, in companies that purely reward goal achievement, there is a focus on measuring only the results without much regard to the process. In these companies, we might observe outcome-oriented and competitive cultures. Another categorization of reward systems might be whether the organization uses rankings or ratings. In a company where the reward system pits members against one another, where employees are ranked against each other and the lower performers receive long-term or short-term punishments, it would be hard to develop a culture of people orientation and may lead to a competitive culture. On the other hand, evaluation systems that reward employee behavior by comparing them to absolute standards as opposed to comparing employees to each other may pave the way to a team-oriented culture. Whether the organization rewards performance or seniority would also make a difference in culture. When promotions are based on seniority, it would be difficult to establish a culture of outcome orientation. Finally, the types of behaviors that are rewarded or ignored set the tone for the culture. Service-oriented cultures reward, recognize, and publicize exceptional service on the part of their employees. In safety cultures, safety metrics are emphasized and the organization is proud of its low accident ratings. What behaviors are rewarded, which ones are punished, and which are ignored will determine how a company’s culture evolves.

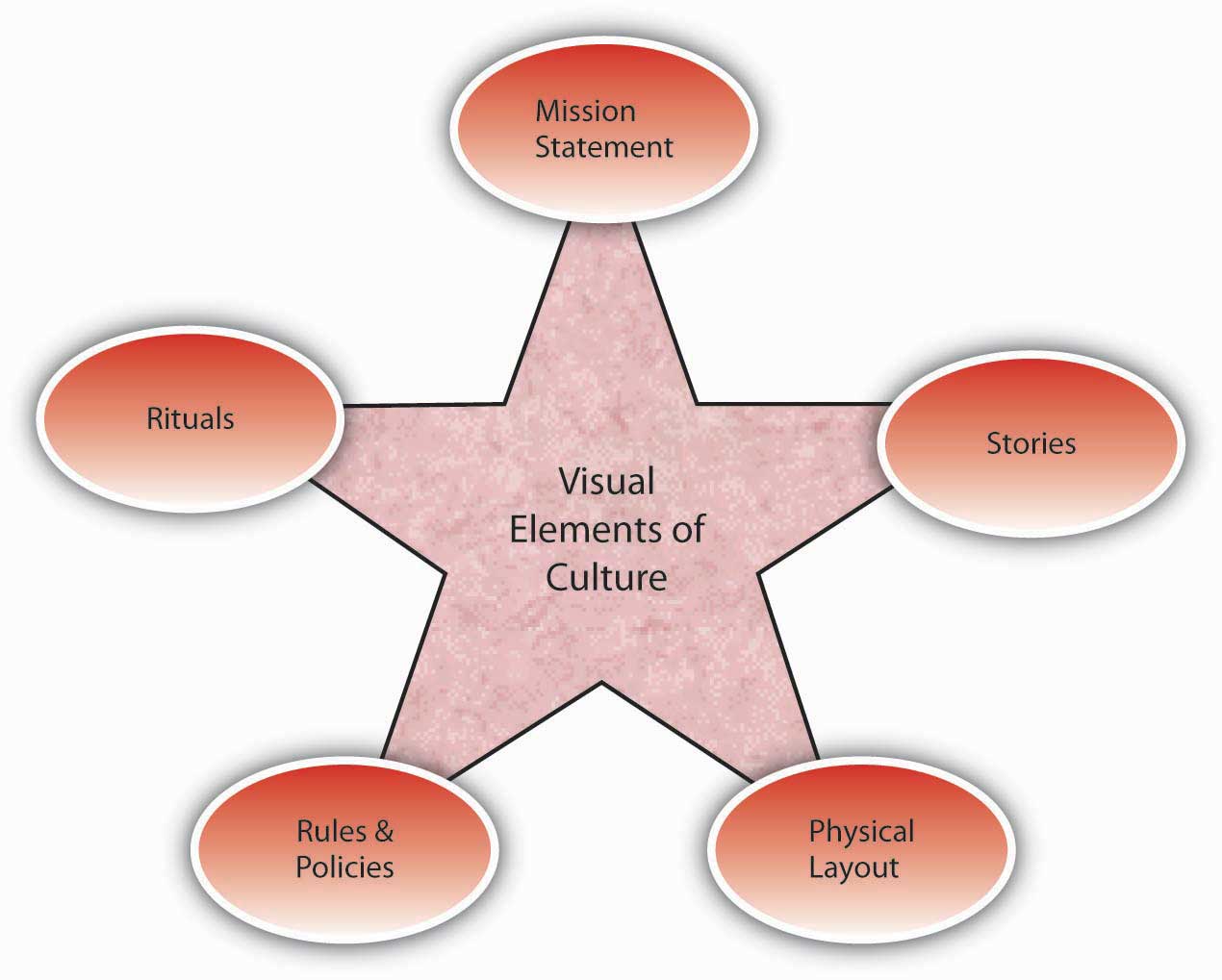

Visual Elements of Organizational Culture

How do you find out about a company’s culture? We emphasized earlier that culture influences the way members of the organization think, behave, and interact with one another. Thus, one way of finding out about a company’s culture is by observing employees or interviewing them. At the same time, culture manifests itself in some visible aspects of the organization’s environment. In this section, we discuss five ways in which culture shows itself to observers and employees.

Mission Statement

A mission statement is a statement of purpose, describing who the company is and what it does. Many companies have mission statements, but they do not always reflect the company’s values and its purpose. An effective mission statement is well known by employees, is transmitted to all employees starting from their first day at work, and influences employee behavior.

Not all mission statements are effective, many are written by public relations specialists focus on external audiences, such statements may not affect how employees act or behave. In fact, some mission statements reflect who the company wants to be as opposed to who they actually are. If the mission statement does not affect employee behavior on a day-to-day basis, it has little usefulness as a tool for understanding the company’s culture. An oft-cited example of a mission statement that had little impact on how a company operates belongs to Enron. Their missions and values statement began, “As a partner in the communities in which we operate, Enron believes it has a responsibility to conduct itself according to certain basic principles.” Their values statement included such ironic declarations as “We do not tolerate abusive or disrespectful treatment. Ruthlessness, callousness and arrogance don’t belong here” (Kunen, 2002).

A mission statement that is taken seriously and widely communicated may provide insights into the corporate culture. For example, the Mayo Clinic’s mission statement is “The needs of the patient come first.” This mission statement evolved from the founders who are quoted as saying, “The best interest of the patient is the only interest to be considered.” Mayo Clinics have a corporate culture that puts patients first. For example, no incentives are given to physicians based on the number of patients they see. Because doctors are salaried, they have no interest in retaining a patient for themselves and they refer the patient to other doctors when needed (Jarnagin & Slocum, 2007).

Rituals

Rituals refer to repetitive activities within an organization that have symbolic meaning (Anand, 2005). Usually rituals have their roots in the history of a company’s culture. They create camaraderie and a sense of belonging among employees. They also serve to teach employees corporate values and create identification with the organization. For example, at the cosmetics firm Mary Kay Inc., employees attend award ceremonies recognizing their top salespeople with an award of a new car—traditionally a pink Cadillac. These ceremonies are conducted in large auditoriums where participants wear elaborate evening gowns and sing company songs that create emotional excitement. During this ritual, employees feel a connection to the company culture and its values, such as self-determination, will power, and enthusiasm (Jarnagin & Slocum, 2007). Another example of rituals is the Saturday morning meetings of Wal-Mart. This ritual was first created by the company founder Sam Walton, who used these meetings to discuss which products and practices were doing well and which required adjustment. He was able to use this information to make changes in Wal-Mart’s stores before the start of the week, which gave him a competitive advantage over rival stores who would make their adjustments based on weekly sales figures during the middle of the following week. Today, hundreds of Wal-Mart associates attend the Saturday morning meetings in the Bentonville, Arkansas, headquarters. The meetings, which run from 7:00 to 9:30 a.m., start and end with the Wal-Mart cheer; the agenda includes a discussion of weekly sales figures and merchandising tactics. As a ritual, the meetings help maintain a small-company atmosphere, ensure employee involvement and accountability, communicate a performance orientation, and demonstrate taking quick action (Schlender, 2005; Wal around the world, 2001).

Rules and Policies

Another way in which an observer may find out about a company’s culture is to examine its rules and policies. Companies create rules to determine acceptable and unacceptable behavior, and thus the rules that exist in a company will signal the type of values it has. Policies about issues such as decision making, human resources, and employee privacy reveal what the company values and emphasizes. For example, a company that has a policy such as “all pricing decisions of merchandise will be made at corporate headquarters” is likely to have a centralized culture that is hierarchical, as opposed to decentralized and empowering. Similarly, a company that extends benefits to both part-time and full-time employees, as well as to spouses and domestic partners, signals to employees and observers that it cares about its employees and shows concern for their well-being. By offering employees flexible work hours, sabbaticals, and telecommuting opportunities, a company may communicate its emphasis on work-life balance. The presence or absence of policies on sensitive issues such as English-only rules, bullying or unfair treatment of others, workplace surveillance, open-door policies, sexual harassment, workplace romances, and corporate social responsibility all provide pieces of the puzzle that make up a company’s culture.

Physical Layout

A company’s building, including the layout of employee offices and other work spaces, communicates important messages about a company’s culture. The building architecture may indicate the core values of an organization’s culture. For example, visitors walking into the Nike Inc. campus in Beaverton, Oregon, can witness firsthand some of the distinguishing characteristics of the company’s culture. The campus is set on 74 acres and boasts an artificial lake, walking trails, soccer fields, and cutting-edge fitness centers. The campus functions as a symbol of Nike’s values such as energy, physical fitness, an emphasis on quality, and a competitive orientation. In addition, at fitness centers on the Nike headquarters, only those wearing Nike shoes and apparel are allowed in. This sends a strong signal that loyalty is expected. The company’s devotion to athletes and their winning spirits is manifested in campus buildings named after famous athletes, photos of athletes hanging on the walls, and honorary statues dotting the campus (Capowski, 1993; Collins & Porras, 1996; Labich & Carvell, 1995; Mitchell, 2002). A very different tone awaits visitors to Wal-Mart headquarters, where managers have gray and windowless offices (Berner, 2007). By putting its managers in small offices and avoiding outward signs of flashiness, Wal-Mart does a good job of highlighting its values of economy.

Stories

Perhaps the most colorful and effective way in which organizations communicate their culture to new employees and organizational members is through the skillful use of stories. A story can highlight a critical event an organization faced and the collective response to it, or can emphasize a heroic effort of a single employee illustrating the company’s values. The stories usually engage employee emotions and generate employee identification with the company or the heroes of the tale. A compelling story may be a key mechanism through which managers motivate employees by giving their behavior direction and energizing them toward a certain goal (Beslin, 2007). Moreover, stories shared with new employees communicate the company’s history, its values and priorities, and serve the purpose of creating a bond between the new employee and the organization.

For example, you may already be familiar with the story of how a scientist at 3M invented Post-it notes. Arthur Fry, a 3M scientist, was using slips of paper to mark the pages of hymns in his church choir, but they kept falling off. He remembered a super-weak adhesive that had been invented in 3M’s labs, and he coated the markers with this adhesive. Thus, the Post-it notes were born. However, marketing surveys for the interest in such a product were weak, and the distributors were not convinced that it had a market. Instead of giving up, Fry distributed samples of the small yellow sticky notes to secretaries throughout his company. Once they tried them, people loved them and asked for more. Word spread, and this led to the ultimate success of the product. As you can see, this story does a great job of describing the core values of a 3M employee: Being innovative by finding unexpected uses for objects, persevering, and being proactive in the face of negative feedback (Higgins & McAllester, 2002).

Exploration Activity

As a Job Candidate, How Would You Find Out If You Are a Good Fit?

- Do your research. Talking to friends and family members who are familiar with the company, doing an online search for news articles about the company, browsing the company’s Web site, and reading their mission statement would be a good start.

- Observe the physical environment. Do people work in cubicles or in offices? What is the dress code? What is the building structure? Do employees look happy, tired, or stressed? The answers to these questions are all pieces of the puzzle.

- Read between the lines. For example, the absence of a lengthy employee handbook or detailed procedures might mean that the company is more flexible and less bureaucratic.

- How are you treated? The recruitment process is your first connection to the company. Were you treated with respect? Do they maintain contact with you, or are you being ignored for long stretches at a time?

- Ask questions. What happened to the previous incumbent of this job? What does it take to be successful in this firm? What would their ideal candidate for the job look like? The answers to these questions will reveal a lot about the way they do business.

- Listen to your gut. Your feelings about the place in general, and your future manager and coworkers in particular, are important signs that you should not ignore.

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Daniel, L., & Brandon, C. (2006). Finding the right job fit. HR Magazine, 51, 62–67; Sacks, D. (2005). Cracking your next company’s culture. Fast Company, 99, 85–87.

Creating Culture Change

How Do Cultures Change?

Culture is the DNA of a company and team, and is resistant to change efforts. Unfortunately, many organizations may not even realize that their current culture constitutes a barrier against organizational productivity and performance. Changing company culture may be the key to the company turnaround when there is a mismatch between an organization’s values and the demands of its environment.

Certain conditions may help with culture change. For example, if an organization is experiencing failure in the short run or is under threat of bankruptcy or an imminent loss of market share, it would be easier to convince managers and employees that culture change is necessary. A company can use such downturns to generate employee commitment to the change effort. However, if the organization has been successful in the past, and if employees do not perceive an urgency necessitating culture change, the change effort will be more challenging. Sometimes the external environment may force an organization to undergo culture change.

Mergers and acquisitions are another example of an event that changes a company’s culture. In fact, the ability of the two merging companies to harmonize their corporate cultures is often what makes or breaks a merger effort. When Ben & Jerry’s was acquired by Unilever, Ben & Jerry’s had to change parts of its culture while attempting to retain some of its unique aspects. Corporate social responsibility, creativity, and fun remained as parts of the culture. In fact, when Unilever appointed a veteran French executive as the CEO of Ben & Jerry’s in 2000, he was greeted by an Eiffel tower made out of ice cream pints, Edith Piaf songs, and employees wearing berets and dark glasses. At the same time, the company had to become more performance oriented in response to the acquisition. All employees had to keep an eye on the bottom line. For this purpose, they took an accounting and finance course for which they had to operate a lemonade stand (Kiger, 2005). Achieving culture change is challenging, and many companies ultimately fail in this mission.

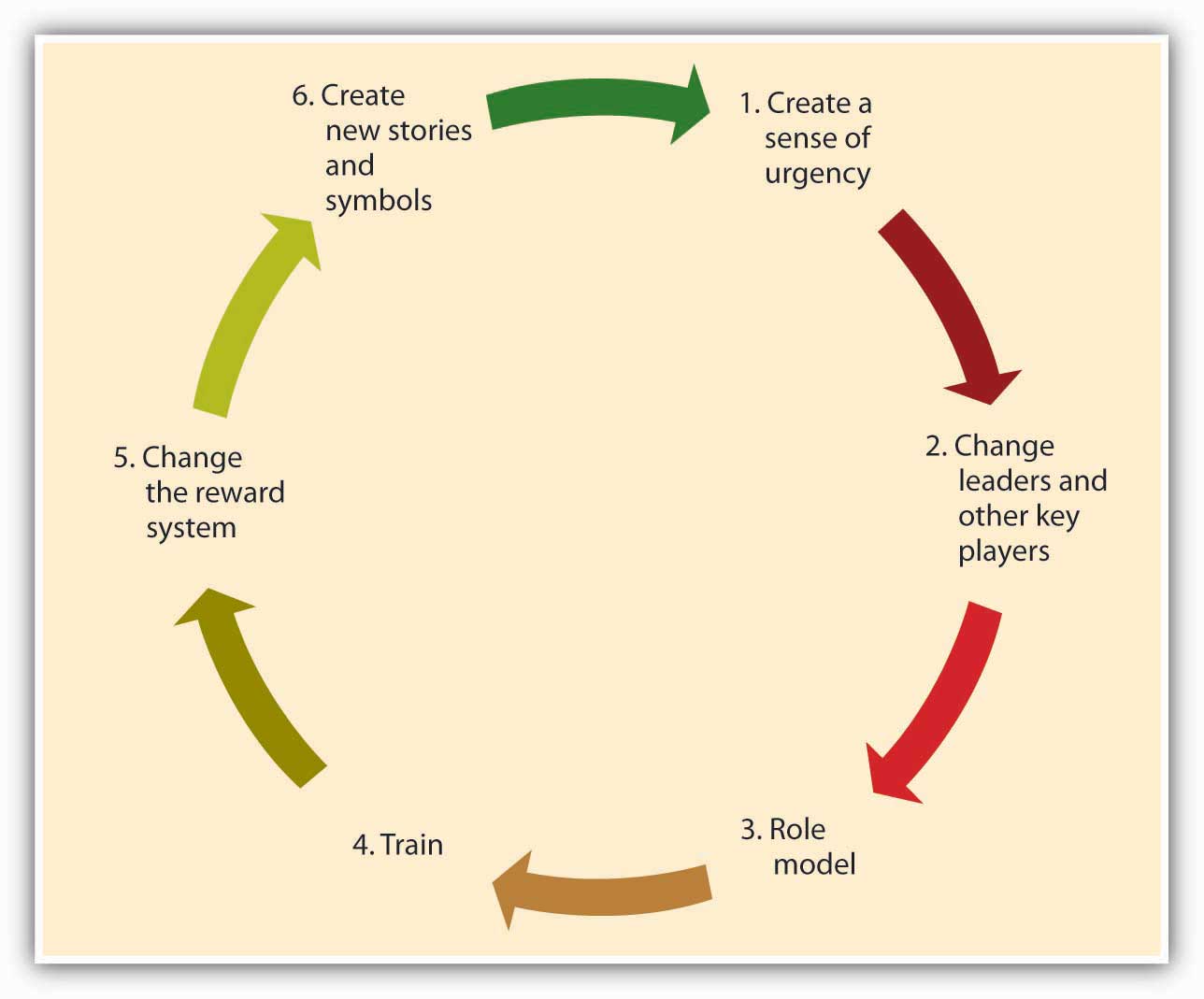

Research and case studies of companies that successfully changed their culture indicate that the following six steps increase the chances of success (Schein, 1990). 1) Create a sense of urgency, 2) Change leaders and other key players, 3) Role model, 4) Train, 5) Change the reward system, and 6) Create new stories and symbols. Each of these steps involves much work–culture change is a difficult but potentially rewarding process.

References

- Allen, T. D., Eby, L. T., & Lentz, E. (2006). Mentorship behaviors and mentorship quality associated with formal mentoring programs: Closing the gap between research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 567–578.

- Anand, N. (2005). Blackwell encyclopedic dictionary of organizational behavior. Cambridge: Wiley.Arnold, J. T. (2007, April). Customers as employees. HR Magazine, 77–82.

- Arogyaswamy, B., & Byles, C. H. (1987). Organizational culture: Internal and external fits. Journal of Management, 13, 647–658.

- Arogyaswamy, B., & Byles, C. M. (1987). Organizational culture: Internal and external fits. Journal of Management, 13, 647–658.

- Badrtalei, J., & Bates, D. L. (2007). Effect of organizational cultures on mergers and acquisitions: The case of DaimlerChrysler. International Journal of Management, 24, 303–317.

- Barney, J. B. (1986). Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review, 11, 656–665.

- Bauer, T. N., & Green, S. G. (1998). Testing the combined effects of newcomer information seeking and manager behavior on socialization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 72–83.

- Bauer, T. N., Bodner, T., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Tucker, J. S. (2007). Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 707–721.

- Berner, R. (2007, February 12). My Year at Wal-Mart. Business Week, 4021, 70–74.

- Beslin, R. (2007). Story building: A new tool for engaging employees in setting direction. Ivey Business Journal, 71, 1–8.

- Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2003). Going the extra mile: Cultivating and managing employee citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Executive, 17, 60–71.

- Bower, J. L. (2001). Not all M&As are alike—and that matters. Harvard Business Review, 79, 92–101.

- Boyle, M. (2004, November 15). Kraft’s arrested development. Fortune, 150, 144.

- Capowski, G. S. (1993, June). Designing a corporate identity. Management Review, 82, 37–41.

- Charan, R. (2006, April). Home Depot’s blueprint for culture change. Harvard Business Review, 84, 60–70.

- Chatman, J. A., & Eunyoung Cha, S. (2003). Leading by leveraging culture. California Management Review, 45, 20–34.

- Chatman, J. A., & Eunyoung Cha, S. (2003). Leading by leveraging culture. California Management Review, 45, 19–34.

- Chatman, J. A., & Jehn, K. A. (1991). Assessing the relationship between industry characteristics and organizational culture: How different can you be? Academy of Management Journal, 37, 522–553.

- Chatman, J. A., & Jehn, K. A. (1994). Assessing the relationship between industry characteristics and organizational culture: How different can you be? Academy of Management Journal, 37, 522–553.

- Christie, L. (2005). America’s most dangerous jobs. Survey: Loggers and fisherman still take the most risk; roofers record sharp increase in fatalities. CNN/Money. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2005/08/26/pf/jobs_jeopardy/.

- Clark, D. (2007, October 15). Why Silicon Valley is rethinking the cubicle office. Wall Street Journal, 250, p. B9.

- Collins, J., & Porras, J. I. (1996). Building your company’s vision. Harvard Business Review, 74, 65–77.

- Conley, L. (2005, April). Cultural phenomenon. Fast Company, 93, 76–77.

- Copeland, M. V. (2004, July). Best Buy’s selling machine. Business 2.0, 5, 92–102.

- Deutschman, A. (2004, December). The fabric of creativity. Fast Company, 89, 54–62.

- Driscoll, K., & McKee, M. (2007). Restorying a culture of ethical and spiritual values: A role for leader storytelling. Journal of Business Ethics, 73, 205–217.

- Durett, J. (2006, March 1). Technology opens the door to success at Ritz-Carlton. Retrieved January 28, 2009, from http://www.managesmarter.com/msg/search/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1002157749.

- Elswick, J. (2000, February). Puttin’ on the Ritz: Hotel chain touts training to benefit its recruiting and retention. Employee Benefit News, 14, 9.

- Erdogan, B., Liden, R. C., & Kraimer, M. L. (2006). Justice and leader-member exchange: The moderating role of organizational culture. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 395–406.

- Fisher, A. (2005, March 7). Starting a new job? Don’t blow it. Fortune, 151, 48.

- Fitch, S. (2004, May 10). Soft pillows and sharp elbows. Forbes, 173, 66–78.

- Ford, R. C., & Heaton, C. P. (2001). Lessons from hospitality that can serve anyone. Organizational Dynamics, 30, 30–47.

- Giberson, T. R., Resick, C. J., & Dickson, M. W. (2005). Embedding leader characteristics: An examination of homogeneity of personality and values in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1002–1010.

- Gordon, G. G. (1991). Industry determinants of organizational culture. Academy of Management Review, 16, 396–415.

- Greene, J., Reinhardt, A., & Lowry, T. (2004, May 31). Teaching Microsoft to make nice? Business Week, 3885, 80–81.

- Herman, J., & Wernle, B. (2007, August 13). The book on Bob Nardelli: Driven, demanding. Automotive News, 81, 42.

- Higgins, J. M., & McAllester, C. (2002). Want innovation? Then use cultural artifacts that support it. Organizational Dynamics, 31, 74–84.

- Hofmann, D. A., Morgeson, F. P., & Gerras, S. J. (2003). Climate as a moderator of the relationship between leader-member exchange and content specific citizenship: Safety climate as an exemplar. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 170–178.

- Hofmann, M. A. (2007, January 22). BP slammed for poor leadership on safety. Business Insurance, 41, 3–26.

- Jarnagin, C., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (2007). Creating corporate cultures through mythopoetic leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 36, 288–302.

- Jermier, J. M., Slocum, J. W., Jr., Fry, L. W., & Gaines, J. (1991, May). Organizational subcultures in a soft bureaucracy: Resistance behind the myth and facade of an official culture. Organization Science, 2, 170–194.

- Jive Software. (2008). Careers. Retrieved November 20, 2008, from http://www.jivesoftware.com/company.

- Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (1997). Applicant personality, organizational culture, and organization attraction. Personnel Psychology, 50, 359–394.

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Wanberg, C. R. (2003). Unwrapping the organizational entry process: Disentangling multiple antecedents and their pathways to adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 779–794.

- Kerr, J., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (2005). Managing corporate culture through reward systems. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 130–138.

- Kerr, J., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (2005). Managing corporate culture through reward systems. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 130–138.

- Kerr, J., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (2005). Managing corporate culture through reward systems. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 130–138.

- Kiger, P. J. (April, 2005). Corporate crunch. Workforce Management, 84, 32–38.

- Kim, T., Cable, D. M., & Kim, S. (2005). Socialization tactics, employee proactivity, and person-organization fit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 232–241.

- Klein, H. J., & Weaver, N. A. (2000). The effectiveness of an organizational level orientation training program in the socialization of new employees. Personnel Psychology, 53, 47–66.

- Kolesnikov-Jessop, S. (2005, November). Four Seasons Singapore: Tops in Asia. Institutional Investor, 39, 103–104.

- Kotter, J. P., & Heskett, J. L. (1992). Corporate culture and performance. New York: Free Press.

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342.

- Kuehner-Herbert, K. (2003, June 20). Unorthodox branch style gets more so at Umpqua. American Banker, 168, 5.

- Kunen, J. S. (2002, January 19). Enron’s vision (and values) thing. The New York Times, p. 19.

- Labich, K., & Carvell, T. (1995, September 18). Nike vs. Reebok. Fortune, 132, 90–114.

- Lok, P., Westwood, R., & Crawford, J. (2005). Perceptions of organisational subculture and their significance for organisational commitment. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54, 490–514.

- Marcoulides, G. A., & Heck, R. H. (1993, May). Organizational culture and performance: Proposing and testing a model. Organizational Science, 4, 209–225.

- Markels, A. (2007, April 23). Dishing it out in style. U.S. News & World Report, 142, 52–55.

- Miles, S. J., & Mangold, G. (2005). Positioning Southwest Airlines through employee branding. Business Horizons, 48, 535–545.

- Mitchell, C. (2002). Selling the brand inside. Harvard Business Review, 80, 99–105.

- Morris, B., Burke, D., & Neering, P. (2006, January 23). The best place to work now. Fortune, 153, 78–86.

- Moscato, D. (2005, April). Using technology to get employees on board. HR Magazine, 50, 107–109.

- Motivation secrets of the 100 best employers. (2003, October). HR Focus, 80, 1–15.

- Mouawad, J. (2008, November 16). Exxon doesn’t plan on ditching oil. International Herald Tribune. Retrieved November 16, 2008, from http://www.iht.com/articles/2008/11/16/business/16exxon.php.

- Nohria, N., Joyce, W., & Roberson, B. (2003, July). What really works. Harvard Business Review, 81, 42–52.

- O’Reilly, C. A., III, Chatman, J. A., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

- O’Reilly, III, C. A., Chatman, J. A., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

- Piercy, C. W., & Lee, S. K. (2020). Reconsidering ‘Ties’: The Sociotechnical Job Search Network. International Journal of Business Communication, 2329488420965680.

- Probst, G., & Raisch, S. (2005). Organizational crisis: The logic of failure. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 90–105.

- Rubis, L., Fox, A., Pomeroy, A., Leonard, B., Shea, T. F., Moss, D., Kraft, G., & Overman, S. (2005). 50 for history. HR Magazine, 50, 13, 10–24.

- Sarros, J. C., Gray, J., & Densten, I. L. (2002). Leadership and its impact on organizational culture. International Journal of Business Studies, 10, 1–26.

- Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Schlender, B. (1998, June 22). Gates’ crusade. Fortune, 137, 30–32.

- Schlender, B. (2005, April 18). Wal-Mart’s $288 billion meeting. Fortune, 151, 90–106.

- Schlender, B. (2007, December 10). Bill Gates. Fortune, 156, 54.

- Schneider, B., Salvaggio, A., & Subirats, M. (2002). Climate strength: A new direction for climate research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 220–229.

- Sheridan, J. (1992). Organizational culture and employee retention. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 1036–1056.

- Smalley, S. (2007, December 3). Ben & Jerry’s bitter crunch. Newsweek, 150, 50.

- Smith, S. (2007, November). Safety is electric at M. B. Herzog. Occupational Hazards, 69, 42.

- Sorensen, J. B. (2002). The strength of corporate culture and the reliability of firm performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 70–91.

- Stegmeier, D. (2008). Innovations in office design: The critical influence approach to effective work environments. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

- Tennissen, M. (2007, December 19). Second BP trial ends early with settlement. Southeast Texas Record.

- The Ritz-Carlton Company: How it became a “legend” in service. (2001, Jan–Feb). Corporate University Review, 9, 16.

- Thompson, J. (2005, September). The time we waste. Management Today, pp. 44–47.

- Thompson, S. (2006, September 18). Kraft CEO slams company, trims marketing staff. Advertising Age, 76, 3–62.

- Wal around the world. (2001, December 8). Economist, 361, 55–57.

- Wal-Mart Stores Inc. (2008). Investor frequently asked questions. Retrieved November 20, 2008, from http://walmartstores.com/Investors/7614.aspx.

- Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 373–385.

- Weber, G. (2005, February). Preserving the counter culture. Workforce Management, 84, 28–34.

- Wesson, M. J., & Gogus, C. I. (2005). Shaking hands with a computer: An examination of two methods of organizational newcomer orientation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1018–1026.

- Westrum, R. (2004, August). Increasing the number of guards at nuclear power plants. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 24, 959–961.

- Why culture can mean life or death for your organization. (2007, September). HR Focus, 84, 9.

A system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs that show employees what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior

Factors that allow a company to perform more effectively than competitors (e.g., capacity, production, culture, etc.).

Shared standards of acceptable behavior by groups.

Taken for granted beliefs about human nature and reality

shared principles, standards, and goals.

visible, tangible aspects of organizational culture.

A culture marked by many shared beliefs in shared assumptions, artifacts, and values.

a useful or valuable thing, person, or quality.

a person or thing whose presence or behavior is likely to cause embarrassment or put one at a disadvantage.

A culture that emerges within different departments, teams, branches, or geographic locations.

shared values and beliefs that are in direct opposition to the values of the broader organizational culture

The process of learning the norms, rules, and culture at a new organization.

Individuals who influence others in teams and organizations.

Behaviors which others look to as an example to be imitated (for better or worse)

the kinds of behaviors and outcomes it chooses to reward and punish.

an often vague statement of purpose, describing who the company is and what it does

repetitive activities within an organization that have symbolic meaning

Messages about shared experiences, company lore, exemplary behavior, etc. which transmit values and assumptions about organization or team culture.