4 Processing with Rights in Mind

What Is Archival Processing?

Archival processing is the combination of tasks and decisions required to organize an archival collection and make it available for research use, and it refers to both arrangement and description of collections. Though technically separate functions, arrangement and description are often done in concert with one another, one informing the other and happening more or less concurrently.

Arrangement is “the process of organizing materials with respect to their provenance and original order, to protect their context and to achieve physical or intellectual control over the materials” (Society of American Archivists, 2022b). The principles of provenance and original order guide archivists during arrangement. Provenance tells us that materials from different sources should not be intermingled. Original order dictates that when the creator’s original organization is present and discernible, it is better to retain it than to create a new artificial arrangement. Both principles are about protecting context and relationships between files and documents. Context in archival collections is vitally important to fully understand the content of collections. To obscure context is to risk obscuring the meaning of the documents that are included in a collection.

Description is “the process of creating a set of data representing an archival resource or component thereof” (Society of American Archivists, 2022e). The function of description is to create access to archival collections. It can take many forms but is most often represented in finding aids. Finding aids are guides to collections that include narrative summaries of the contents as well as inventories of the physical location of materials. Narrative notes summarize the types of documents present in the collection, notable individuals documented by the collection, activities of the creator that are documented in the collection, and date ranges of the material in the collection.

Description of archival collections is often in the aggregate. Individual items are rarely described, but groupings of similar types of material often are. For example, rather than describing each individual letter in a collection, all of the correspondence would be described as a whole, focusing on the overall nature of the letters, common themes, and recurring names.

The first step of processing is conducting a collection analysis. This is a high-level review of the collection’s contents that results in a processing plan. At this point, the archivist ascertains whether original order is present. If it is, the archivist focuses their analysis on learning the creator’s organizational system and identifying anomalies. If the original order is not present, the archivist focuses their analysis on identifying intellectual units within the collection to create a logical and useful arrangement. One approach is to identify documents that share a format, for example, correspondence or photographs. Another approach is to identify documents that serve the same function, for example, business records or teaching files. Very often, archivists employ a combination of approaches, organizing some materials according to their format and some according to their function. The Hanley’s Bell Street Funeral Home records at Emory University is a good example of the combined approach, with a series for the funeral home’s business records and a series of the Hanley family’s personal papers, as well as series for photographs, printed material, and memorabilia.

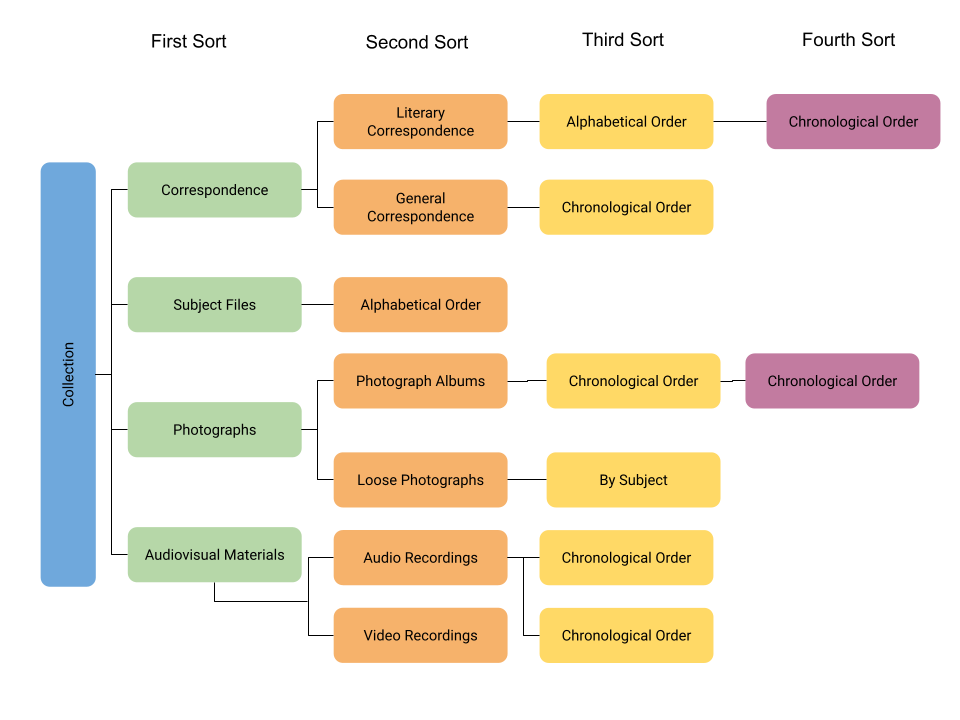

Following the collection analysis, processing archivists will physically sort the collection to bring together all components of the categories they identified during the collection analysis (see Figure 4.1). Sorting happens multiple times over the course of the processing project. During a first-level sort, the archivist will bring together all of the correspondence, all of the creator’s writings, and all of the photographs, for example. A second-level sort may then be necessary to organize the writings between poetry and prose works. During a third-level sort, the archivist would bring together all of the drafts of each publication. This enables the archivist to ensure they’re arranging and describing all of the related material at the same time. The archivist is better able to describe documents consistently and can make decisions about arrangement and description with all relevant materials in front of them. Each grouping is likely to require different levels of sorting. While writings often require the significant effort described above, correspondence may not. Once all of the correspondence is physically together, it may be enough to put it in chronological order without any further divisions by type.

After the collection is sorted, archivists rehouse material and provide basic conservation interventions. Original file folders are replaced with acid-free folders, original boxes are replaced with acid-free boxes, documents are flattened, fasteners may be removed, and torn documents are placed in plastic sleeves to prevent further damage. Archivists also label file folders at this stage, transcribing original titles from the creator’s folders or applying devised titles based on information derived from the documents themselves.

Throughout this process, the archivist will keep notes about the creator’s life and activities, the kinds of records that are present in the collection, and other individuals who are documented. These notes will form the basis of the finding aid, the creation of which is the final step of processing.[1] Because the archivist is already gathering this kind of information during processing, they are uniquely suited to conducting copyright analysis.

Why Integrate Rights Analysis into Processing?

Collection analysis/processing and copyright/risk analysis begin with the same questions:

- Who created this item?

- For what purpose did they create this item?

- When did they create this item?

Integrating rights analysis with existing processing workflows leverages the archivist’s existing collection expertise and eliminates duplication of labor because they are already gathering information necessary for robust rights analysis as part of their regular processing work.

Detailed processing requires granular interaction with collection material. Although every item is neither described individually nor read word for word, most documents are at least skimmed in order to classify them. To accurately arrange and describe materials, archivists may scrutinize significant portions of collections more closely. For example, memos in a collection of business records may need to be read to determine which project they’re associated with. In another example, an author’s manuscript drafts may require close review to determine order or identify duplication.

Because archivists gain such intimate knowledge of the contents of archival collections during processing, they are uniquely positioned to evaluate the intellectual property landscape of a collection. During and immediately after processing, this knowledge is at its height and easiest to leverage. Integrating rights analysis into processing takes advantage of the knowledge of the processing archivist and helps streamline workflows. It eliminates the need for someone (often not the processing archivist) to return to the collection at a later date (often many years or decades later) to conduct a basic rights analysis, frequently without the benefit of the processing archivist’s knowledge.

Because archivists are accustomed to arranging and describing archival collections in aggregations, they are well-suited to identifying and analyzing groups of materials with similar copyright considerations. It is important to note that aggregations that are useful for access to collection material are not necessarily the same aggregations that should be analyzed for copyright analysis. Archivists should be aware of the need to analyze the entire collection during copyright assessment, not just within categories. We discuss this more in the following section, “What to Look for During Processing.”

We do not recommend integrating rights review into minimal processing workflows. Although minimal processing is a powerful tool to provide timely access to collections, it is not granular enough to support thorough copyright review for building digital collections. During minimal processing, archivists do not typically interact closely enough with collection materials to identify information necessary for rights analysis, such as rightsholders beyond the creator of the collection or publication dates for published material in the collection. Detailed processing (defined here as file- or item-level arrangement and description), as opposed to minimal processing, also gives archivists an important opportunity to identify and mark red flags, or higher risk items, in the collection. It is vital to an adequate rights analysis to know what materials may require special attention or be off the table for digitization entirely.

What to Look for During Processing

Who Was the Collection Creator?

- Is the collection an individual’s papers?

- Is the collection a business’s records?

Understanding the provenance of the materials is critical to copyright analysis, especially for archival materials, which are often unpublished. For example, the duration of copyright for unpublished works of corporate authorship is 120 years from the date of creation, whereas copyright for unpublished works by an individual expires 70 years after the author’s death (see 17 U.S. Code § 302; Copyright Act, 1976f).

If the Creator Was an Individual

- Were they a literary figure or prominent politician?

- Were they a community member without national notoriety whose papers were acquired to document local history?

- Were they a person of industry whose papers were acquired because of their profession?

Depending on the identity of the creator, the nature of the records present in the collection may vary. The personal papers of an author will likely include a more significant volume of published works that generate revenue than those of a local community member. The community member’s papers may include far more unpublished material than the literary figure’s papers. In addition to their own personal papers, a professional’s papers may include records created in their capacity as an employee at a business, which may mean that the copyright owner is actually the business.

- What is their death date?

The term of copyright for unpublished works is the life of the creator plus 70 years. Unpublished works created by authors who have been deceased for 70 years or more are in the public domain and can be widely shared in any way your institution may wish (e.g., in digital or physical exhibits). Very young creators will hold copyright in their unpublished materials for many decades to come, which may make those documents a higher risk for digitization and sharing online.

Are Other Copyright Holders Represented in the Collection?

- Who were they in relation to the collection’s creator?

- What is the creator’s relationship to records whose copyright is held by another?

For example, as mentioned above, if a collection includes records created by an employee of a business (i.e., works for hire), the business is the copyright holder, not the individual.

Understanding and documenting the major copyright holders represented in the collection at the time of processing will help assess risk later. Major copyright holders may be individuals and organizations who hold the rights to a significant volume of material in the collection. They also may be significant because of their notoriety/fame, because of the risk associated with particular items to which they hold copyright, or because they are known to be litigious.

There may be institutional reasons to identify someone as a significant copyright holder as well, and it is worth considering your institution’s relationships with donors and community stakeholders to ensure you are capturing all necessary information. For example, different donors will be more or less enthusiastic about digitizing and disseminating their papers. Even if you have a strong fair use justification for digitization or a license to reuse the materials from the deed of gift (see Chapter 3: Evaluating Licensing and Permissions for Archival Materials), proceeding with public display of digitized material without the donor’s approval may cause a rift in your institution’s relationship with that donor. Likewise, your institution may serve communities, particularly historically excluded communities, who have customs and laws prohibiting dissemination of certain kinds of information. This is true of many indigenous tribes whose cultural patrimony exists in predominantly white, colonizer institutions. Though your institution may legally be allowed to digitize and disseminate certain documents (e.g., perhaps their age puts them into the public domain), ethically it may not be in your institution’s best interests to do so without the cooperation and partnership of the community that is being documented.

The list of names you create will likely look very similar to the list of names being gathered for scope and content notes and will probably include the following:

- significant correspondents,

- business and/or romantic partners of the creator,

- family members,

- and/or individuals whose creative works are present in the collection.

However, your list of major copyright holders may be more inclusive than names provided in finding aids. For example, a highly litigious person who is known to be very protective of their intellectual property may have written a single letter to the creator of the collection being processed. This is unlikely to warrant description in the finding aid but is still important to note for copyright analysis purposes to protect your institution from legal harm following digitization or reuse.

Dates

- Is the creator of an item deceased?

- If so, when did they die?

- When were items in the collection published?

Dates are as important for copyright assessment as they are for access. Knowing the death dates of the creators of the material will help you determine whether items are in the public domain or still under copyright. It’s unlikely that you will know or be able to ascertain the life dates for every major copyright holder represented in a collection. You may be able to estimate an approximate death date or associate them with a particular period in time via the dates of the material in the collection. This will help you assess risk, though it may not enable you to determine an exact copyright status.

Knowing the publication dates of published materials will also help you determine copyright status. Dates are another way to intellectually aggregate similar materials for copyright assessment that may differ from the aggregations used for processing. Copyright status for published materials is complicated and depends significantly on the publication date and the law governing copyright at the time of publication.[2]

Be on the lookout as well for materials that bear other kinds of risk. There may be other intellectual property issues in a collection, such as trademarks, that can impact a risk assessment. There may also be right to privacy or rights of publicity considerations that bear mentioning.[3] While privacy is a separate issue from copyright and not necessarily pertinent to an analysis of copyright, it is pertinent to an overall risk assessment when considering a collection for digitization. For more information on conducting a risk assessment, see Chapter 2: Identifying Your Institutional Risk Tolerance.

Aggregations for Access vs. Aggregations for Copyright

Aggregations of material that are useful for access may not be the most useful aggregations for copyright analysis, so it will also be important to track record types that share a similar copyright status across the collection. For example, terms of copyright are different for unpublished works than for published works, as noted above, while fair use is more favorable for published works than for unpublished works. Yet, published and unpublished works by the collection creator as well as other authors may be present in every series of a collection. For example, an article published by the collection creator may exist in draft form in a writings series and in the final published form in a printed material series. Likewise, the writings series may include drafts of works that the creator never published. Although the creator may be the copyright holder for the published article and the unpublished works and although these works are physically organized in the same series, the term of copyright is different, and your risk analysis must treat them differently.

Another example of this issue is correspondence, which is a common and logical grouping in archival collections. Arranging all of the letters in a collection together facilitates access to information about the creator’s work and relationships and is one way to provide researchers with both a broad and a detailed overview of the creator’s life. However, it’s a very complicated grouping from an intellectual property perspective. Correspondence series can include letters written by hundreds of authors from all backgrounds. Depending on the collection, a correspondence series could include letters from unknown individuals as well as the most famous artists and politicians. It requires very careful risk analysis and will not be as straightforward as an analysis of more homogenous groupings of material.

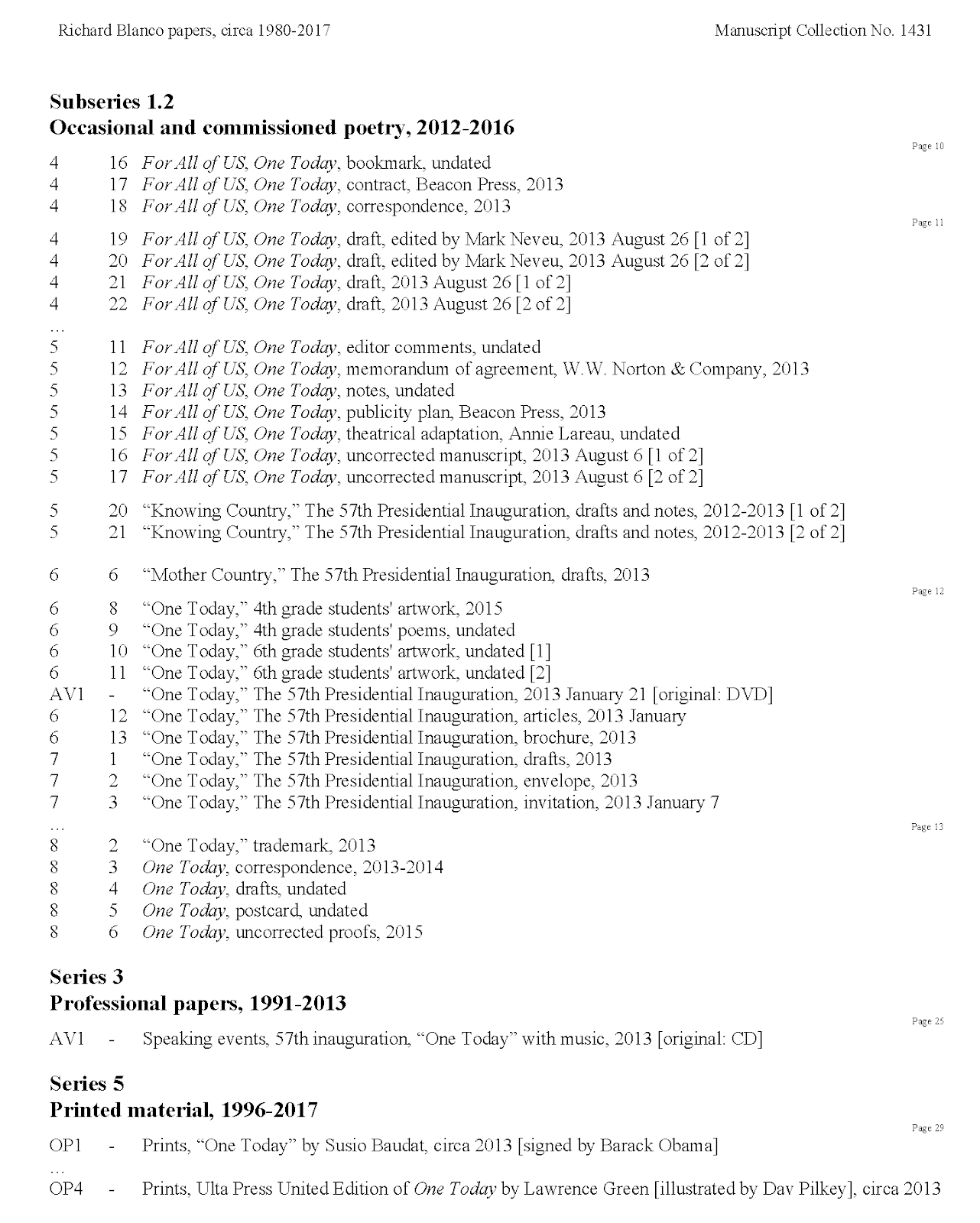

We can see these issues illustrated in this finding aid for the Richard Blanco papers at Emory University’s Rose Library (see Figure 4.2). Let’s use Blanco’s poem “One Today” to look at how copyright applies to similar material across a collection.

Blanco was the fifth presidential inaugural poet and composed the poem “One Today” for Barack Obama’s second inauguration in 2013. Subsequently, Blanco repurposed the title for a memoir, For All of Us, One Today: An Inaugural Poet’s Journey. He also published a version of the poem as a children’s book, illustrated by Dav Pilky, and artist Susio Baudat created a commemorative print of the poem. This poem is one of Blanco’s most important works, and the collection includes multiple iterations and derivatives of the original poem across multiple series, each with a slightly different copyright status, as well as correspondence about the poem and books, children’s art inspired by the poem, photographs of Blanco reading at the inauguration, and records documenting publication of the works.

Though Blanco holds copyright in most of the items in the above image, some are published and some are unpublished. The children’s book has multiple copyright holders, as do the prints and the recording, and the business records have corporate copyright holders. Risk will need to be assessed differently depending on who the copyright holder is, how many people hold the copyright to a single item, and whether the item is considered published or unpublished. It’s important to remember that sometimes even categories that seem straightforward on the surface can be complex upon further examination. Your analysis should take these complexities into account, and your documentation should also account for the myriad locations where items with similar copyright status are present within a collection.

Special Considerations

Certain formats may require a slightly different approach. As mentioned in Chapter 2: Identifying Your Institutional Risk Tolerance, copyright for audiovisual material is especially complicated (see “What Types of Collections Do You Hold?” in Chapter 2). There are likely multiple copyright holders for any given recording. For example, in an oral history, the interviewer may hold copyright in the questions asked, while the interviewee holds copyright in their answers to questions, and if the interview is being recorded by a third party, they may hold additional copyright in the recording itself. These intertwined layers of rights increase risk and make it harder to seek permissions, either due to the number of copyright holders represented and capacity to conduct the necessary research or due to lack of information about the total number of copyright holders for a particular item. For these reasons, you may wish to create separate digitization workflows and justifications for a/v digitization.

Visual art and photography require their own special considerations. Works of visual art, including paintings, drawings, and still photographic images, among other formats, are governed by the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990 (VARA, see 17 U.S. Code § 106A, Copyright Act, 1976c). VARA affords visual artists certain rights in their works regardless of who holds copyright or physical ownership of the work, including rights of attribution and integrity. Familiarity with VARA and the rights it protects will be critical to an assessment of visual arts collections in your institution. Furthermore, art photography typically generates revenue for creators and will likely be higher risk in terms of digitization and sharing. Copyright analysis should focus on the type of photographs present in a collection and whether they were created by professionals or are snapshots taken by the creator and/or their friends and family. If professional photographs are present, particularly in large numbers, it is worth documenting the photographers and studios who took the photos.

Items such as memorabilia, artifacts, and scrapbooks present another category of special considerations. While useful articles such as clothing or crockery are not copyrightable, design elements that are part of the useful articles may be copyrightable. However, it can be difficult to ascertain who holds copyright in these design elements. Memorabilia and artifacts may also include trademarks, which is another kind of intellectual property risk that must be considered. For example, a collection in your holdings may include a commemorative mug from an event. The mug is not copyrightable as a useful article, but if the mug bears a trademarked logo or copyrighted special design, those elements may be more risky when considering digitization. Scrapbooks can be complicated because they often contain items created by many authors, from photographs to letters to newspaper clippings, and therefore represent multiple copyright holders.

For all of these items, transformative fair use is an important consideration when assessing risk for digitization. For ephemeral items and memorabilia, their original purpose was functional or commemorative, not educational. Creating a digital surrogate for research and educational use could be considered transformative according to the Association for Research Libraries’ Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Academic and Research Libraries (2012). Scrapbooks themselves are a transformative use of the items that they contain. The meaning of the scrapbook as a record is the sum of its individual parts, most of which were created for a different purpose than commemorating the life of the book’s creator. Digitizing scrapbooks is a further transformation of the item into an educational resource. Though the rights landscape for these items can be complex, they can be some of the best candidates for digitization based on fair use.

Capturing Information

Much of the information necessary to conduct rights analysis is already captured by archivists during processing. The kinds of information necessary for a robust and impactful finding aid correspond to the kinds of information needed to assess risk in a collection, so archivists should not fear that adding a rights framework to their workflows will add significant extra burden to their work.

Capture information in whatever way works best for you and serves the needs of your institution. Processing work plans and notes documents are two potentially helpful locations. Archives management tools such as ArchivesSpace may also include space to record rights information. Ultimately, the reason you are capturing this information should inform where you permanently record it. If the information will be used by coworkers outside of the processing unit, particularly colleagues responsible specifically for rights-review work, consider creating a report that can be shared more broadly.

A post-processing rights and risk assessment report is a powerful tool that can both record and effectively disseminate an archivist’s knowledge about a collection. It records the information at the time when the archivist knows the most about a collection and can help the archivist translate their knowledge into useful information for nonarchivist colleagues.

The template we created at Emory (see Appendix D) mirrors many of our other templates and is therefore easier for our archivists to use because it’s familiar. Processing archivists are responsible for completing the report at the end of each processing project, though they may work on it throughout the duration of the project as they identify important information. The goal of the report is to capture everything the processing archivist has learned at the point when their knowledge is at its height. The template includes sections for the archivist to describe the intellectual property landscape of each series or, if the collection does not have series, each type of material in the collection. There are also sections to record other kinds of risk present in the collection, list the names of major copyright holders, and enumerate any licensing/permissions work or digitization that has already been done.

The report is kept permanently in the administrative file for the collection and can be shared with colleagues in other divisions when needed. Because the audience for the report is broader than Rose Library, the template also includes sections to record licensing information in the deed of gift and collection- and series-level descriptive information (taken from the finding aid). The template effectively collocates information from several different documents into a single report and enables colleagues outside of the Rose Library to locate all that information in one place.

It is important to note that completion of the post-processing rights and risk assessment report does not include final licensing or fair use analysis work. Other staff will use the report if and when the collection is discussed as a priority for digitization. The information in the report will allow decision makers to ascertain whether the risk associated with a collection is too high to pursue a digitization project. It will also tell them how much additional copyright clearance work will need to be done if they pursue digitization. Processing archivists at Rose Library are not responsible for verifying copyright status of individual items, sending permission letters to copyright holders, or writing fair use justifications. If necessary, that work will be done by others later in the digitization workflow.

Exercise: Designing an Effective Report Template

Create a post-processing report template to capture the copyright information you need to adequately assess the risk associated with digitizing a collection.

Questions to consider when creating your report:

- Who is the audience for the report? Is it internal to your unit or will it be used by colleagues in other parts of your organization?

- What functions will it facilitate? Will it help with digitization? Other kinds of reuse? Both?

- What other information is important to that function? Is it appropriate to include that information in the report as well?

- How can the template’s design help with training processing archivists to use it?

- Where does the report fit into various workflows?

Test the template using a sample collection at your institution, preferably one that you’ve processed and know well, if possible.

Share the draft with others on your team.

- Does it capture the information they expect it to?

- Did they find it easy to understand?

- Where did they see gaps in the document?

Incorporate their feedback into any revisions you make to the template. It’s important to continue revising the template as more archivists use it to create reports and as others use it as a resource in rights work.

Alternate Exercise: Use Emory’s template (see Appendix D) and test with a collection at your institution. Revise the template to make it your own, based on your institution’s needs.

- For more information concerning processing of archival collections at Emory’s Rose Library, see our Collections Services Manual. ↵

- Cornell University Library (2022) maintains a helpful chart summarizing copyright terms according to publication status and date. ↵

- See Legal Information Institute (n.d.a) for more information on the right of publicity and the right to privacy (Legal Information Institute, n.d.b). ↵