6 Case Study: Emory University Libraries

In the fall of 2019, Jennifer Gunter King (the director of the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University Libraries) and Lisa Macklin (the Emory Libraries associate vice provost and university librarian) chartered a small task force of two scholarly communications librarians and two archivists (the authors of this text) to examine and revise workflows associated with copyright review for digitization of Rose Library collections. Historically, although our divisions worked closely together to prepare collections for digitization, our workflows were separate and did not account for dependencies as well as they should have. They were also not scalable, causing us to digitize far less than our stakeholders requested. We were charged with the following tasks:

- Examining existing workflows,

- Revising them to incorporate a more scalable, risk-based approach,

- Creating additional templates, forms, and guidelines for doing the work, and

- Incorporating additional librarians and archivists into the workflows where possible to provide additional support.

Historical Workflows

Archival Processing

Historically, Rose Library archivists have not been a significant part of copyright work at Emory Libraries. Because we know the collections well, we may have answered occasional questions from the copyright and scholarly communications librarian or other stakeholders to help with copyright analysis but were otherwise not expected to participate in rights analysis, rights clearance, or fair use justification. Our purview had been primarily focused on processing and creating access for collections and consulting occasionally on proposals for digitizing collections. The new workflows make introductory copyright analysis part of the arrangement and description process.

Processing in the Rose Library is iterative. All collections are minimally processed during accessioning.[1] They receive basic physical stabilization, are reboxed if necessary, and an inventory of each box’s contents is provided as part of a short finding aid with basic biographical/historical and scope and contents notes. We provide minimal processing in an effort to make collections available for research as soon as possible following acquisition. If a collection is small or especially straightforward, the archivist may choose to provide more granular arrangement and description, including file- or item-level processing. However, for detailed processing to occur on most collections, Rose Library leadership must identify the collection as a priority for granular access.

After priority collections are identified, they are assigned to processing teams. Processing teams consist of one professional archivist and two graduate student processing assistants. The archivist determines the overall processing plan and assigns portions of the collection to each student for arrangement and description. The archivist is responsible for writing the processing plan and keeping it updated as plans change and decisions are made. The archivist uses the processing plan and other communication tools to ensure consistency during the project. Each team member is responsible for the arrangement and description of their assigned portion of the collection, and the archivist provides final editing and description of any elements that apply to the entire collection. When a draft of the finding aid is completed, it is reviewed by other archivists in the unit as well as the curator who acquired the collection. After any changes have been made or questions answered, the finding aid is published online and the collection is reopened for research use.

Copyright Analysis

In 2019, Emory University Libraries began scaling up its digital library program in preparation for the launch of a new digital repository. Initially developed for hosting digitized archives and special collections materials, Emory Digital Collections was slated for beta launch in spring 2020. Until this time, all rights-review work for digital collections was being performed at the item level by our copyright and scholarly communications librarian (who is one of the authors of this text, Melanie T. Kowalski, and who occupied this position from 2013–2022). This librarian’s position description allocated approximately 20% of her time to rights review. Limiting this work to one individual at 8 hours per week created bottlenecks in our workflows. Some of the inherent challenges included the following:

- Item-level rights review was simply not sustainable. Since the launch of Emory Digital Collections, we have ingested just over 34,000 digital images. The sheer scale of content to review could not be managed by 20% of a single person’s work week. To address this workflow imbalance, we experimented with hiring student workers. However, we found that training student employees for rights review was a time-consuming and lengthy process. Given the high turnover rate of student employees, we found the return on investment did not yield an increase in review productivity.

- While the pace of rights review remained slow, the pace of digitization did not. In order to keep pace with digitization requests, the digitization team produced substantial volumes of material that required review. As their pace exceeded that of the copyright and scholarly communications librarian, a backlog of uningested digitized content developed. This upside-down workflow was detrimental because not infrequently the copyright and scholarly communications librarian would determine that certain pieces were too risky to share online from a copyright standpoint, so they never should have been digitized (unless it was needed for preservation).

- In these rights reviews, the copyright and scholarly communications librarian was duplicating much of the work that archivists had already done when they processed the collections (e.g., researching creation dates and names of creators to determine whether materials were still protected by copyright). Since that work had not been documented with the intent of using it to perform rights-review assessments, the materials needed to be assessed by staff again. This duplication of effort was inefficient and contributed to the bottleneck at the point of rights review.

Digitization

In general, Rose Library special collections material may be selected for digitization in three different ways:

- To fulfill a patron order for a high-quality scan of material.

- To support internal library projects like exhibition work or a library-sponsored digital humanities project.

- To support a formal digitization project when the Libraries’ leadership identifies a collection or a portion of a collection that we would like to have digitized and included in Emory Digital Collections, our public-facing digital library.

While each of these is an important part of the digitization landscape, this case study will focus on the third scenario and how, historically, the digitization process for inclusion in our digital library happened.

In the past, anyone in the Libraries could submit a request for a digitization project via an online form. Most commonly archivists or curators working in the Rose Library would be the ones to suggest digitizing Rose collections, but other colleagues in other units of the Libraries or our affiliated digital scholarship center would also occasionally initiate a project to digitize special collections material. The proposal form, which included a brief overview of the project, a note about any known deadlines or preservation concerns, and the overall project scope was submitted to the head of digitization services. This individual then shared the proposal with our Digital Collections Steering Committee composed of collection managers from across the Emory Libraries, representatives from the metadata team, and the copyright and scholarly communications librarian. If the committee approved moving forward with a digitization project, the head of digitization services would slot the project into the digitization queue. As the actual digitization was about to get underway, the head of digitization services would set up a preservation and metadata review with representatives from the owning library, the preservation team, and metadata services. In this meeting, the metadata services representative would gather the information about a collection to pass along to the copyright and scholarly communications librarian to inform the rights-review work.

Formation of the Copyright Workflow Task Force

Once our group was convened, our first task was education and cross-training of its members. The archivists and one scholarly communications librarian took the semester-long Copyright X course offered by Harvard. We met weekly, along with the copyright and scholarly communications librarian who had taken the course previously, to discuss the week’s readings and lectures. This allowed us to ask each other questions, report on conversations we had each had in our respective sections of the course, and ensure we were moving forward with similar understandings of what we had learned. The archivists also provided an introduction to archival arrangement and description for the scholarly communications librarians. This cross-training provided a baseline of shared knowledge for everyone and was also a trust-building experience as we learned together and began to identify where we had misunderstood each other’s historical workflows.

We then moved on to evaluating our workflows together. To begin, we reviewed the existing workflows in each of our units. We ensured that we all understood the workflows as they were currently in use and took time to discuss dependencies, constraints, and capacity issues that might affect any changes we decided to make later. Paying particular attention to bottlenecks and gaps, we discussed areas where changes could be made to increase efficiency and introduce scalability. We also identified areas where tasks could be distributed so all the responsibility didn’t fall on a single individual. Finally, we identified where additional forms and templates could help, including new deed addenda and permissions letter templates.

The Revised Workflow

Archival Processing

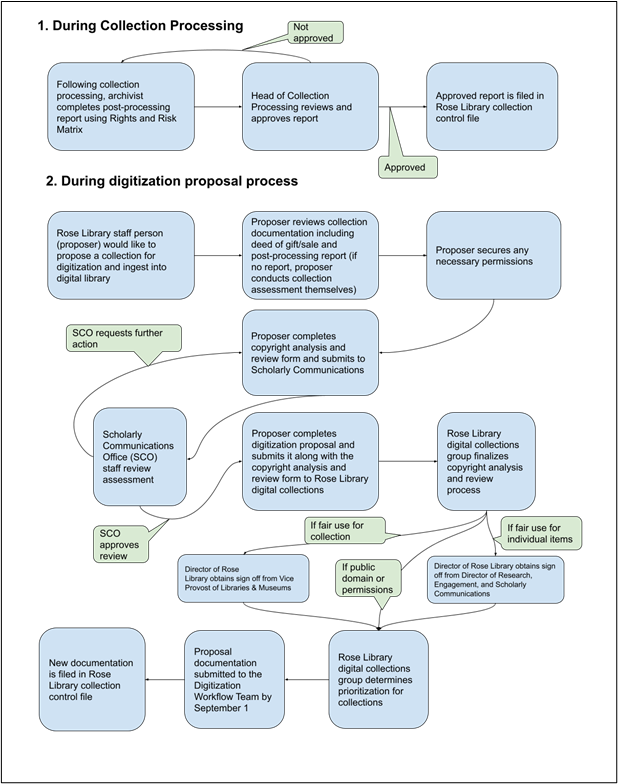

Overall, a few tasks were added to the processing workflow (see Figure 6.1). Archivists now complete a post-processing rights and risk assessment report following file- or item-level processing of collections. It captures the contextual and intellectual property information discussed in Chapter 4: Processing with Rights in Mind. The report repurposes much of the information from the collection finding aid. After we designed the initial template, we tested it using an already-processed collection to ensure it captured the information we needed and to ascertain how much time an archivist might expect to need to complete the report. It took about 2 hours, which was a significant improvement over the 8-10 hours it might have taken the copyright librarian to gather the same information using the old workflow.

Archivists at Rose Library do not complete this form after minimal processing because the archivist’s knowledge of the collection is not granular enough at that point. Minimally processed collections are also not candidates for digitization at Emory.

Revising the workflow for archival processing also required us to think differently about the kinds of analysis archivists performed during arrangement and description. Archivists in the Rose Library already had some knowledge of copyright law since many had taken basic copyright workshops as part of their own professional development over the years. However, in this new workflow, we were asking archivists to serve as an authority in the rights-review process. While we did not need them to become copyright experts, they did need to have more than a passing familiarity with concepts like fair use. Therefore one additional deliverable for our task force was a training plan for archivists and other Rose staff who would interact with the new workflows.

We wanted to leverage the knowledge of the processing archivists in a new risk-assessment framework, but we needed them to see themselves as integral to the process. Like many cultural heritage organizations, Rose Library operates with a very lean staff, so adding responsibilities can feel stressful, and the team members were skeptical that they had the expertise and the time to write the reports. Implementing the new report template required a lot of socialization and reassurance that the processing archivists would be able to provide the necessary information without spending an exorbitant amount of extra time completing the work. We did this by emphasizing that the work required a perspective shift more than it required extensive new training. As mentioned before, most of the information the report captures is repackaged from the existing finding aid or other notes archivists keep during processing. We also identified “copyright experts” in the Rose Library, staff who had received in-depth copyright training and education, who could act as consultants when processing archivists needed help.

Copyright Analysis

As a result of this change in workflows, copyright analysis work now begins much earlier in the collection lifecycle, and that work is disbursed more broadly across the organization. As demonstrated above, new collections are processed with risk and copyright assessment for digitization in mind. For collections that have already been processed, the initial review is completed by the Rose Library staff member proposing digitization of the materials. The proposer reviews collection documentation, including deeds of gift or sale. If they determine that permissions are needed, they secure those permissions using a new suite of templates for permission letters and deed addenda that our task force created. Then, the proposer completes the copyright analysis and review form and submits it to the Scholarly Communications Office for review. As a reviewer rather than author, the copyright and scholarly communications librarian serves their intended role as a consultant on copyright issues and questions. Once this form is reviewed and approved, the proposer uses the information from the form to complete a digitization proposal that they submit to the Rose Library Digital Strategy Team.

By distributing the copyright analysis labor across archival staff, this new rights-review process allows for quicker assessment and analysis of the copyright implications of a given collection. Multiple archival staff can work on multiple collections concurrently. Serving in a consultant role, the copyright librarian’s 20% time allocation can be better utilized in consulting on challenging or complex questions rather than reviewing works at the item level for a single collection.

Digitization

As mentioned above, the Rose Library has a Digital Strategy Team that plans, proposes, and prioritizes all digital projects and digitization proposals. The chair of this team is responsible for managing the digitization proposal process, including ensuring that the copyright analysis and review form is completed for each collection the Library proposes for digitization and that all necessary permissions have been requested, public domain status asserted, or a fair use justification thoughtfully articulated. This form is also where the owning library makes recommendations about visibility levels and sharing options such as whether an image should be in high or low resolution, downloadable, or available only behind an institutional login. This form is then shared with the Scholarly Communications Office for approval or additional feedback and becomes part of the final digitization proposal that the Rose Library director submits for approval.

In the Emory Libraries, the approver for digitization and online dissemination of collections changes based on several factors, including the legal justification the Libraries uses for sharing collection material and the potential risk that the Libraries may incur. In our case, the head of the Scholarly Communications Office can approve moving forward with sharing collection material online if either of the following is true: (1) it is in the public domain or (2) we have received permission from the copyright holder to digitize and share it online. However, digitizing and disseminating an entire copyrighted collection because we are asserting that these actions are a fair use requires the approval of the associate vice provost and university librarian.

Once approval is secured, the Rose Library Digital Strategy Team selects which proposals to prioritize for a given year and submits this list to the Collections Steering Committee for review and approval. This committee is composed of individuals with either content stewardship or digital collection management responsibilities from across the Emory Libraries. Previously, these proposals were submitted on a rolling basis throughout the year, but the committee now receives, evaluates, and prioritizes proposals at the beginning of each fiscal year and then reevaluates halfway through the year to see if new priorities have emerged or if collections slated for digitization need to be reranked or removed from the list.

Throughout the year, as digitization on various collections progresses, the Rose Library’s head of digital archives coordinates with the Digitization Workflow Group (a group of functional leads including the copyright and scholarly communications librarian, the head of digitization services, the head of metadata services, and the digital preservation program manager) to ensure the delivery of collection material to the digitization lab and to coordinate information sharing about metadata, and to facilitate any necessary reviews of physical collections to ensure material is stable and able to be digitized safely.

- Accessioning is the process whereby an institution takes “intellectual and physical custody of materials, often under legal or policy authority” (Society of American Archivists, 2022a). ↵