6 Chapter 6 – Marketing Basics

What Marketing Is All About

Because the purpose of business is to create a customer, the business enterprise has two—and only two—basic functions: marketing and innovation. Marketing and innovation produce results; all the rest are costs. Marketing is the distinguishing, unique function of the business. -Peter Drucker[1]

Marketing is defined by the American Marketing Association as “the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.”[2] Putting this formality aside, marketing is about delivering value and benefits: creating products and services that will meet the needs and wants of customers (perhaps even delighting them) at a price they are willing to pay and in places where they are willing to buy them. Marketing is also about promotional activities such as advertising and sales that let customers know about the goods and services that are available for purchase. Successful marketing generates revenue that pays for all other company operations. Without marketing, no business can last very long. It is that important and that simple—and it applies to small business.

Marketing is applicable to goods, services, events, experiences, people, places, properties, organizations, businesses, ideas, and information.[3]

There are several concepts that are basic to an understanding of marketing: the marketing concept, customer value, the marketing mix, segmentation, target market, the marketing environment, marketing management, and marketing strategy.

The Marketing Concept…and Beyond

The marketing concept has guided marketing practice since the mid-1950s.[4] The concept holds that the focus of all company operations should be meeting the customer’s needs and wants in ways that distinguish a company from its competition. However, company efforts should be integrated and coordinated in such a way to meet organizational objectives and achieve profitability. Perhaps not surprisingly, successful implementation of the marketing concept has been shown to lead to superior company performance.[5] “The marketing concept recognizes that there is no reason why customers should buy one organization’s offerings unless it is in some way better at serving the customers’ wants and needs than those offered by competing organizations. Customers have higher expectations and more choices than ever before. This means that marketers have to listen more closely than ever before.”[6]

Sam Walton, the founder of Walmart, put it best when he said, “There is only one boss: the customer. And he can fire everybody in the company, from the chairman on down, simply by spending his money somewhere else.”[7] Small businesses are particularly suited to abiding by the marketing concept because they are more nimble and closer to the customer than are large companies. Changes can be made more quickly in response to customer wants and needs.

The societal marketing concept emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, adding to the traditional marketing concept. It assumes that a “company will have an advantage over competitors if it applies the marketing concept in a manner that maximizes society’s well-being”[8] and requires companies to balance customer satisfaction, company profits, and the long-term welfare of society. Although the expectation of ethical and responsible behavior is implicit in the marketing concept, the societal marketing concept makes these expectations explicit.

Small business is in a very strong position in keeping with the societal marketing concept. Although small businesses do not have the financial resources to create or support large philanthropic causes, they do have the ability to help protect the environment through green business practices such as reducing consumption and waste, reusing what they have, and recycling everything they can. Small businesses also have a strong record of supporting local causes. They sponsor local sports teams, donate to fund-raising events with food and goods or services, and post flyers for promoting local events. The ways of contributing are virtually limitless.

The holistic marketing concept is a further iteration of the marketing concept and is thought to be more in keeping with the trends and forces that are defining the twenty-first century. Today’s marketers recognize that they must have a complete, comprehensive, and cohesive approach that goes beyond the traditional applications of the marketing concept.[9] A company’s “sales and revenues are inextricably tied to the quality of each of its products, services, and modes of delivery and to its image and reputation among its constituencies. [The company] markets itself through everything it does, its substance as well as its style. It is that all-encompassing package that the organization then sells.”[10] What we see in the holistic marketing concept is the traditional marketing concept on steroids. Small businesses are natural for the holistic marketing concept because the bureaucracy of large corporations does not burden them. The size of small businesses makes it possible, perhaps imperative, to have fluid and well-integrated operations.

Customer Value

The definition of marketing specifically includes the notion that offerings must have value to customers, clients, partners, and society at large. This necessarily implies an understanding of what customer value is. Customer value is discussed at length in Chapter 2 but we can define it simply as the difference between perceived benefits and perceived costs. Such a simple definition can be misleading, however, because the creation of customer value will always be a challenge—most notably because a company must know its customers extremely well to offer them what they need and want. This is complicated because customers could be seeking Functional value (a product or a service performs a utilitarian purpose), Social value (a sense of relationship with other groups through images or symbols), emotional value (the ability to evoke an emotional or an affective response), Epistemic value (offering novelty or fun), or Conditional value (derived from a particular context or a sociocultural setting, such as shared holidays)—or some combination of these types of value. (See Chapter 2 for a detailed discussion of the types of value.)

Marketing plays a key role in creating and delivering value to a customer. Customer value can be offered in a myriad of ways. In addition to superlative ice cream, for example, the local ice cream shop can offer a frequent purchase card that allows for a free ice cream cone after the purchase of fifteen ice cream products at the regular price. Your favorite website can offer free shipping for Christmas purchases and/or pay for returns. Zappos.com offers free shipping both ways for its shoes. The key is for a company to know its consumers so well that it can provide the value that will be of interest to them.

Market Segmentation

The purpose of segmenting a market is to focus the marketing and sales efforts of a business on those prospects who are most likely to purchase the company’s product(s) or service(s), thereby helping the company (if done properly) earn the greatest return on those marketing and sales expenditures.[11] Market segmentation maintains two very important things: (1) there are relatively homogeneous subgroups (no subgroup will ever be exactly alike) of the total population that will behave the same way in the marketplace, and (2) these subgroups will behave differently from each other. Market segmentation is particularly important for small businesses because they do not have the resources to serve large aggregate markets or maintain a wide range of different products for varied markets.

The marketplace can be segmented along a multitude of dimensions, and there are distinct differences between consumer and business markets. Some examples of those dimensions are presented in the table below.

LifeLock, a small business that offers identity theft protection services, practices customer type segmentation by separating its market into business and individual consumer segments.

Market Segmentation

| Consumer Segmentation Examples | Business Segmentation Examples |

|---|---|

|

Geographic Segmentation

|

Demographic Segmentation

|

|

Demographic Segmentation

|

Operating Variables

|

|

Psychographic Segmentation

|

Purchasing Approaches: Which to Choose?

|

|

Behavioral Segmentation

|

Situational Factors: Which to Choose?

|

|

Personal Characteristics: Which to Choose?

|

Other Characteristics

|

Source in footnotes[12]

Market segmentation requires some marketing research. The marketing research process is discussed in the section on marketing research.

Target Market

Market segmentation should always precede the selection of a target market. A target market is one or more segments (e.g., income or income + gender + occupation) that have been chosen as the focus for business operations. The selection of a target market is important to any small business because it enables the business to be more precise with its marketing efforts, thereby being more cost-effective. This will increase the chances for success. The idea behind a target market is that it will be the best match for a company’s products and services. This, in turn, will help maximize the efficiency and effectiveness of a company’s marketing efforts:

It is not feasible to go after all customers, because customers have different wants, needs and tastes. Some customers want to be style leaders. They will always buy certain styles and usually pay a high price for them. Other customers are bargain hunters. They try to find the lowest price. Obviously, a company would have difficulty targeting both of these market segments simultaneously with one type of product. For example, a company with premium products would not appeal to bargain shoppers…

Hypothetically, a certain new radio station may discover that their music appeals more to 34–54-year-old women who earn over $50,000 per year. The station would then target these women in their marketing efforts.[13]

Target markets can be further divided into niche markets. A niche market is a small, more narrowly defined market that is not being served well or at all by mainstream product or service marketers. People are looking for something specific, so target markets can present special opportunities for small businesses. They fill needs and wants that would not be of interest to larger companies. Niche products would include such things as paint that transforms any smooth surface into a high-performance dry-erase writing surface or 3D printers. These niche products are provided by small businesses. Niche ideas can come from anywhere.

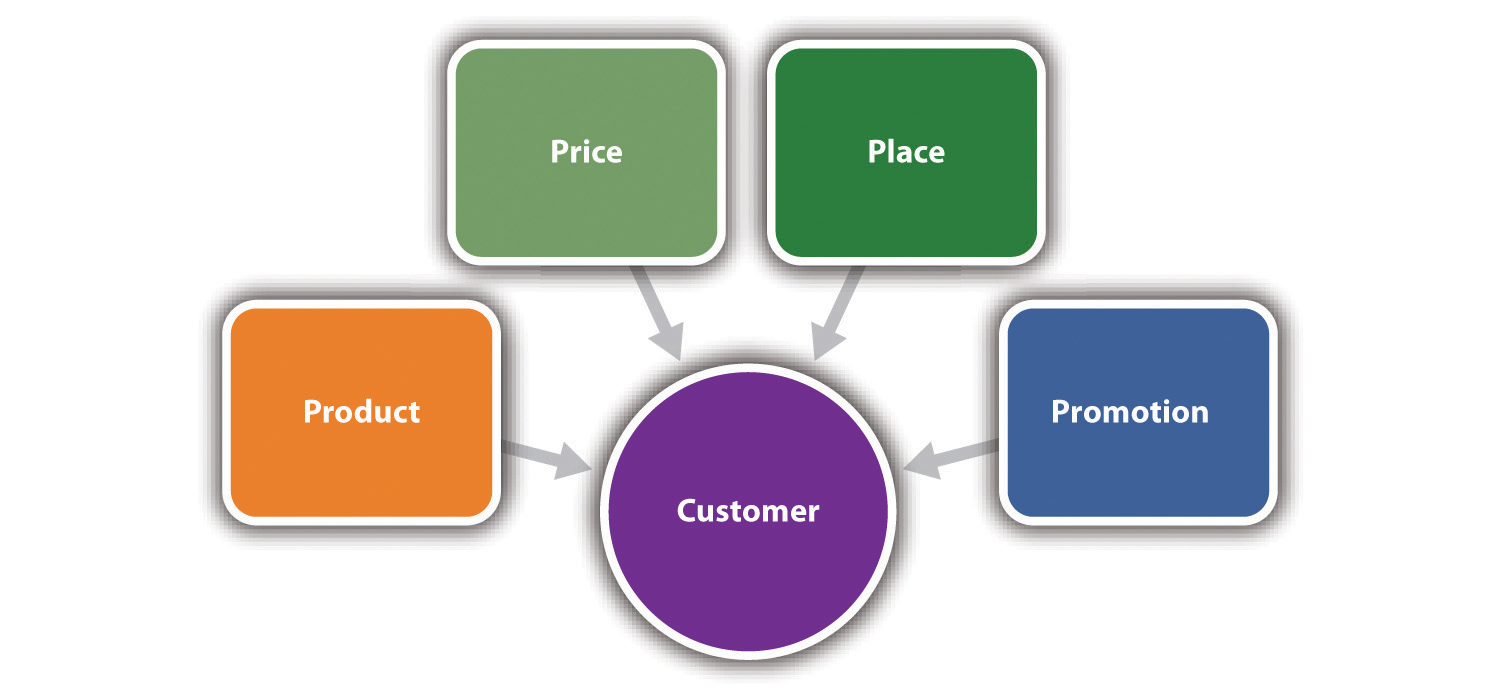

Marketing Mix

Marketing mix is easily one of the most well-known marketing terms. More commonly known as “the four Ps,” the traditional marketing mix refers to the combination of product, price, promotion, and place (distribution). Each component is controlled by the company, but they are all affected by factors both internal and external to the company. Additionally, each element of the marketing mix is impacted by decisions made for the other elements. What this means is that an alteration of one element in the marketing mix will likely alter the other elements as well. They are inextricably interrelated. No matter the size of the business or organization, there will always be a marketing mix. The marketing mix is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7. A brief overview is presented here.

The Marketing Mix

Product

Product refers to tangible, physical products as well as to intangible services. Examples of product decisions include design and styling, sizes, variety, packaging, warranties and guarantees, ingredients, quality, safety, brand name and image, brand logo, and support services. In the case of a services business, product decisions also include the design and delivery of the service, with delivery including such things as congeniality, promptness, and efficiency. Without the product, nothing else happens. Product also includes a company’s website.

Price

Price is what it will cost for someone to buy the product. Although the exchange of money is what we traditionally consider as price, time and convenience should also be considered. Examples of pricing decisions include pricing strategy selection (e.g., channel pricing and customer segment pricing), retail versus wholesale pricing, credit terms, discounts, and the means of making online payments. Channel pricing occurs when different prices are charged depending on where the customer purchases the product. A paper manufacturer may charge different prices for paper purchased by businesses, school bookstores, and local stationery stores. Customer segment pricing refers to charging different prices for different groups. A local museum may charge students and senior citizens less for admission.[14]

Promotion

Having the best product in the world is not worth much if people do not know about it. This is the role of promotion—getting the word out. Examples of promotional activities include advertising (including on the Internet), sales promotion (e.g., coupons, sweepstakes, and 2-for-1 sales), personal sales, public relations, trade shows, webinars, videos on company websites and YouTube, publicity, social media such as Facebook and Twitter, and the company website itself. Word-of-mouth communication, where people talk to each other about their experiences with goods and services, is the most powerful promotion of all because the people who talk about products and services do not have any commercial interest.

Place

Place is another word for distribution. The objective is to have products and services available where customers want them when they want them. Examples of decisions made for place include inventory, transportation arrangements, channel decisions (e.g., making the product available to customers in retail stores only), order processing, warehousing, and whether the product will be available on a very limited (few retailers or wholesalers) or extensive (many retailers or wholesalers) basis. A company’s website is also part of the distribution domain.

Two Marketing Mixes

No matter what the business or organization, there will be a marketing mix. The business owner may not think about it in these specific terms, but it is there nonetheless. Here is an example of how the marketing mix can be configured for a local Italian restaurant (consumer market).

- Product. Extensive selection of pizza, hot and cold sub sandwiches, pasta and meat dinners, salads, soft drinks and wine, homemade ice cream and bakery products; the best service in town; and free delivery.

- Price. Moderate; the same price is charged to all customer segments.

- Promotion. Ads on local radio stations, websites, and local newspaper; flyers posted around town; coupons in ValPak booklets that are mailed to the local area; a sponsor of the local little league teams; ads and coupons in the high school newspaper; and a Facebook presence.

- Place. One restaurant is located conveniently near the center of town with plenty of off-street parking. It is open until 10:00 p.m. on weekdays and 11:30 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays. There is a drive-through for takeout orders, and they have a special arrangement with a local parochial school to provide pizza for lunch one day per week.

Here is an example of how the marketing mix could be configured for a green cleaning services business (business market).

- Product. Wide range of cleaning services for businesses and organizations. Services can be weekly or biweekly, and they can be scheduled during the day, evening, weekends, or some combination thereof. Only green cleaning products and processes are used.

- Price. Moderate to high depending on the services requested. Some price discounting is offered for long-term contracts.

- Promotion. Ads on local radio stations, website with video presentation, business cards that are left in the offices of local businesses and medical offices, local newspaper advertising, Facebook and Twitter presence, trade show attendance (under consideration but very expensive), and direct mail marketing (when an offer, announcement, reminder, or other item is sent to an existing or prospective customer).

- Place. Services are provided at the client’s business site. The cleaning staff is radio dispatched.

The Marketing Environment

The marketing environment includes all the factors that affect a small business. The internal marketing environment refers to the company: its existing products and strategies; culture; strengths and weaknesses; internal resources; capabilities with respect to marketing, manufacturing, and distribution; and relationships with stakeholders (e.g., owners, employees, intermediaries, and suppliers). This environment is controllable by management, and it will present both threats and opportunities.

The external marketing environment must be understood by the business if it hopes to plan intelligently for the future. This environment, not controllable by management, consists of the following components:

- Social factors. For example, cultural and subcultural values, attitudes, beliefs, norms, customs, and lifestyles.

- Demographics. For example, population growth, age, gender, ethnicity, race, education, and marital status.

- Economic environment. For example, income distribution, buying power and willingness to spend, economic conditions, trading blocs, and the availability of natural resources.

- Political and legal factors. For example, regulatory environment, regulatory agencies, and self-regulation.

- Technology. For example, the nature and rate of technological change.

- Competition. For example, existing firms, potential competitors, bargaining power of buyers and suppliers, and substitutes.[15]

- Ethics. For example, appropriate corporate and employee behavior.

The Marketing Environment

Small businesses are particularly vulnerable to changes in the external marketing environment because they do not have multiple product and service offerings and/or financial resources to insulate them. However, this vulnerability is offset to some degree by small businesses being in a strong position to make quick adjustments to their strategies if the need arises. Small businesses are also ideally suited to take advantage of opportunities in a changing external environment because they are more nimble than large corporations that can get bogged down in the lethargy and inertia of their bureaucracies.

Marketing Strategy versus Marketing Management

The difference between marketing strategy and marketing management is an important one. Marketing strategy involves selecting one or more target markets, deciding how to differentiate and position the product or the service, and creating and maintaining a marketing mix that will hopefully prove successful with the selected target market(s)—all within the context of marketing objectives. Differentiationinvolves a company’s efforts to set its product or service apart from the competition. Positioning “entails placing the brand [whether store, product, or service] in the consumer’s mind in relation to other competing products, based on product traits and benefits that are relevant to the consumer.”[16] Segmentation, target market, differentiation, and positioning are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7.

Key Takeaways

- Marketing is a distinguishing, unique function of a business.

- Marketing is about delivering value and benefits, creating products and services that will meet the needs and wants of customers (perhaps even delighting them) at a price they are willing to pay and in places where they are willing to buy them. It is also about promotion, getting the word out that the product or the service exists.

- The marketing concept has guided business practice since the 1950s.

- Customer value is the difference between perceived benefits and perceived costs. There are different types of customer value: functional, social, epistemic, emotional, and conditional.

- Marketing plays a key role is delivering value to the customer.

- Market segmentation, target market, niche market, marketing mix, marketing environment, marketing management, and marketing strategy are key marketing concepts.

- The marketing mix, also known as the four Ps, consists of product, price, promotion, and place.

The Customer

It is very important in marketing to distinguish between the customer and the consumer. The customer, the person or the business that actually buys a product or a service, will determine whether a business succeeds or fails. It is that simple. It does not matter one iota if a business thinks its product or service is the greatest thing since sliced bread if no one wants to buy it. This is why customers play such a central role in marketing, with everything revolving around their needs, wants, and desires. We see the customer focus in the marketing concept, and we see it in the marketing mix.

The Customer and the Marketing Mix

The marketing mix should follow the determination of customer needs, wants, and desires. However, there are instances in which a product is created before the target market is selected and before the rest of the marketing mix is designed. One well-known example is Ivory Soap. This product was created by accident. Air was allowed to work its way into the white soap mixture that was being cooked. The result was Ivory Soap, a new and extraordinarily successful product for Procter & Gamble.[17] Most companies do not have this kind of luck, though, so a more deliberate approach to understanding the customer is critical to designing the right marketing mix.

The consumer is the person or the company that uses or consumes a product. For example, the customer of a dry cleaning service is the person who drops off clothes, picks them up, and pays for the service. The consumer is the person who wears the clothes. Another example is a food service that caters business events. The person who orders lunch on behalf of the company is the customer. The people who eat the lunch are the consumers. The person who selects the catering service could be either or both. It is common for the customer and the consumer to be the same person, but this should not be assumed for all instances. The challenge is deciding whether to market to the customer or the consumer—or perhaps both.

Customer Markets

There are two major types of customer markets: Business-to-business (B2B) customers and individual consumers or end users (individual consumer or end users Business-to-consumer (B2C)). B2B customers are organizations such as corporations; small businesses; government agencies; wholesalers; retailers; and nonprofit organizations, such as hospitals, universities, and museums. In terms of dollar volume, the B2B market is where the action is. More dollars and products change hands in sales to business buyers than to individual consumers or end users.[18] The B2B market offers many opportunities for the small business. Examples of B2B products include office supplies and furniture, machinery, ingredients for food preparation, telephone and cell phone service, and delivery services such as FedEx or UPS.

The B2C market consists of people who buy for themselves, their households, friends, coworkers, or other non-business-related purposes. Examples of B2C products include cars, houses, clothing, food, telephone and cell phone service, cable television service, and medical services. Opportunities in this market are plentiful for small businesses. A walk down Main Street and a visit to the Internet are testaments to this fact.

Understanding the Customer

The better a small business understands its customers, the better off it will be. It is not easy, and it takes time, but knowing who the customers are, where they come from, what they like and dislike, and what makes them tick will be of immeasurable value in designing a successful marketing mix. Being intuitive can and does work…but not for everyone and not all the time. A more systematic and thorough approach to understanding the customer makes much more sense. The problem is that many if not most small businesses probably do not take the time to do what it takes to understand their customers. This is an important part of the reason why so many small businesses fail.

Consumer Behavior

Consumer behavior —“how individuals, groups, and organizations select, buy, use, and dispose of goods, services, ideas, or experiences to satisfy their needs and wants”[19]—is the result of a complex interplay of factors, none of which a small business can control. These factors can be grouped into four categories: personal factors, social factors, psychological or individual factors, and situational factors. It is important that small-business owners and managers learn what these factors are.

- Personal factors. Age, gender, race, ethnicity, occupation, income, and life-cycle stage (where an individual is with respect to passage through the different phases of life, e.g., single, married without children, empty nester, and widow or widower). For example, a 14-year-old girl will have different purchasing habits compared to a 40-year-old married career woman.

- Social factors. Culture, subculture, social class, family, and reference groups (any and all groups that have a direct [face-to-face] or indirect influence on a person’s attitudes and behavior, e.g., family, friends, neighbors, professional groups [including online groups such as LinkedIn], coworkers, and social media such as Facebook and Twitter).[20] For example, it is common for us to use the same brands of products that we grew up with, and friends (especially when we are younger) have a strong influence on what and where we buy. This reflects the powerful influence that family has on consumer behavior.

- Psychological or individual factors. Motivation, perception (how each person sees, hears, touches, and smells and then interprets the world around him or her), learning, attitudes, personality, and self-concept (how we see ourselves and how we would like others to see us). When shopping for a car, the “thud” sound of a door is perceived as high quality whereas a “tinny” sound is not.

- Situational factors. The reason for purchase, the time we have available to shop and buy, our mood (a person in a good mood will shop and buy differently compared to a person in a bad mood), and the shopping environment (e.g., loud or soft music, cluttered or neat merchandise displays, lighting quality, and friendly or rude help). A shopper might buy a higher quality box of candy as a gift for her best friend than she would buy for herself. A rude sales clerk might result in a shopper walking away without making a purchase.

These factors all work together to influence a five-stage buying-decision process (“Five Stages of the Consumer Buying Process”), the specific workings of which are unique to each individual. This is a generalized process. Not all consumers will go through each stage for every purchase, and some stages may take more time and effort than others depending on the type of purchase decision that is involved.[21] Knowing and understanding the consumer decision process provides a small business with better tools for designing and implementing its marketing mix.

Five Stages of the Consumer Buying Process

| Stage | Description | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Problem recognition | Buyer recognizes a problem or need. | Joanne’s laptop just crashed, but she thinks it can be fixed. She needs it quickly. |

| 2. | Information search | Buyer searches for extensive or limited information depending on the requirements of the situation. The sources may be personal (e.g., family or friends), commercial (e.g., advertising or websites), public (e.g., mass media or consumer rating organizations), or experiential (e.g., handling or examining the product). | Joanne is very knowledgeable about computers, but she cannot fix them. She needs to find out about the computer repair options in her area. She asks friends for recommendations, checks out the yellow pages, does a Google search, draws on her own experience, and asks her husband. |

| 3. | Evaluation of alternatives | Buyer compares different brands, services, and retailers. There is no universal process that everyone uses. | Joanne knows that computer repair services are available at the nearby Circuit Place and Computer City stores. Unfortunately, she has had bad experiences at both. Her husband, David, recently took his laptop to a small computer repair shop in town that has been in business for less than a year. He was very pleased. Joanne checks out their website and is impressed by the very positive reviews. None of her friends could recommend anyone. |

| 4. | Purchase decision | Buyer makes a choice. | Joanne decides to take her computer to the small repair shop in town. |

| 5. | Postpurchase behavior | How the buyer feels about the purchase and what he or she does or does not do after the purchase. | Joanne’s laptop was fixed quickly, and the cost was very reasonable. She feels very good about the experience, so she posts a glowing review on the company’s website, recommends the shop to everyone she knows, and plans to go back should the need arise. Had she been unhappy with her experience, she would have posted a negative review on the company’s website, told everyone she knows not to go there, and refuse to go there again. It is this latter scenario that should be every small business’s nightmare. |

Source in footnotes[22]

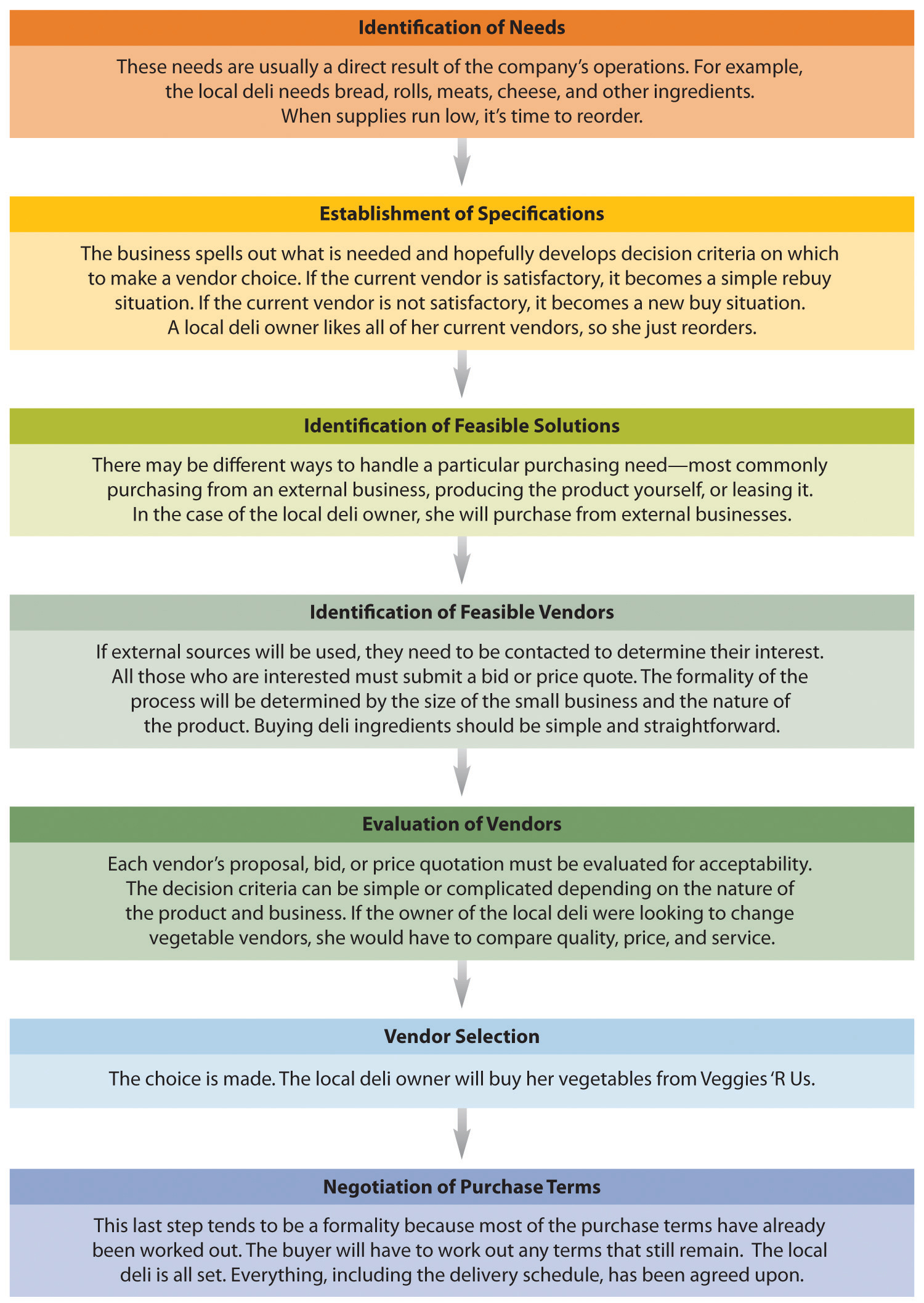

Business Buying Behavior

Understanding how businesses make their purchasing decisions is critical to small businesses that market to the business sector. Purchases by a business are more complicated than purchases by someone making a personal purchase (B2C). B2B purchases vary according to dollar amount, the people involved in the decision process, and the amount of time needed to make the decision,[23] and they involve “a much more complex web of interactions between prospects and vendors in which the actual transaction represents only a small part of the entire purchase process.”[24]

The individual or the group that makes the B2B buying decisions is referred to as the buying center. The buying center consists of “all those individuals and groups who participate in the purchasing decision-making process, who share some common goals and the risks arising from the decision.”[25] The buying center in a small business could be as small as one person versus the twenty or more people in the buying center of a large corporation. Regardless of the size of the buying center, however, there are seven distinct roles: initiator, gatekeeper, user, purchaser or buyer, decider, approver, and influencer.[26] One person could play multiple roles, there could be multiple people in a single role, and the roles could change over time and across different purchase situations.

- Initiator. The person who requests that something be purchased.

- Gatekeeper. The person responsible for the flow of information to the buying center. This could be the secretary or the receptionist that screens calls and prevents salespeople from accessing users or deciders. By having control over information, the gatekeeper has a major impact on the purchasing process.

- User. The person in a company who uses a product or takes advantage of a service.

- Purchaser or buyer. The person who makes the actual purchase.

- Decider. The person who decides on product requirements, suppliers, or both.

- Approver. The person who authorizes the proposed actions of the decider or the buyer.

- Influencer. The person who influences the buying decision but does not necessarily use the product or the service. The influencer may assist in the preparation of product or service specifications, provide vendor ideas, and suggest criteria for evaluating vendors.

The B2B Buying Process

Source in footnotes[27]

The B2B purchasing process for any small business will be some variation of the process described in “The B2B Buying Process”. The specifics of the process will depend on the nature of product, the simplicity of the decision to be made, and the number of people involved. Clearly the purchasing process for a single-person business will be much simpler than for a multiproduct business of 400 employees.

The Customer Experience

Customer experience is one of the great frontiers for innovation. – Jeneanne Rae[28]

Customer experience refers to a customer’s entire interaction with a company or an organization. The experience will range from positive to negative, and it begins when any potential customer has contact with any aspect of a business’s persona—the company’s marketing, all representations of the total brand, and what others say about the experience of working with the business.[29]

Customer Experience in the B2C Market

Customers will experience multiple touchpoints (i.e., all the communication, human, and physical interactions that customers experience during their relationship life cycle with a small business)[30] during their visit. In a retail situation, a customer will experience the store design and layout; the merchandise that is carried and how it is displayed; the colors, sounds, and scents in the store; the cleanliness of the store; the lighting; the music; the helpfulness of the staff; and the prices. In a business situation, a customer will experience the design and layout of the reception and office areas, the colors chosen for carpeting and furniture, the friendliness and helpfulness of the reception staff, and the demeanor of the person or people to be seen. The experience also occurs when a customer communicates with a company via telephone; e-mail; the company website; and Facebook, Twitter, or other social media.

The Role of Store Design in Customer Experience

Store design plays a very important role in a customer’s experience. Good customer experiences “from the perspective of the customer…are useful (deliver value), usable (make it easy to find and engage with the value), and enjoyable (emotionally engaging so that people want to use them).”[31] A customer experience can be a one-time occurrence with a particular company, but experiences are more likely to happen across many time frames.[32] The experience begins at the point of need awareness and ends at need extinction.[33]

B2C customer experiences also involve emotional connections. When small businesses make emotional connections with customers and prospects, there is a much greater chance to forge bonds that will lead to repeat and referral business. When a business does not make those emotional connections, a customer may go elsewhere or may work with the business for the moment—but never come back and not refer other customers or clients to the business.[34]

Many businesses may not appreciate that 50 percent of a customer’s experience is about how a customer feels. Emotions can drive or destroy value.[35] “Customers will gladly pay more for an experience that is not only functional but emotionally rewarding. Companies skilled at unlocking emotional issues and building products and services around them can widen their profit margins…Great customer experiences are full of surprising ‘wow’ moments.”[36]

Small businesses should learn and think about how to market a great B2C customer experience, not just a product or a service.[37] Design an experience that is emotionally engaging by mapping the customer’s journey[38]—and then think of ways to please, perhaps even delight, the customer along that journey. A history of sustained positive customer experiences will increase the chances that a business will be chosen over its competition.[39]

Meaningful, memorable, fun, unusual and unexpected experiences influence the way customers perceive you in general and feel about you in particular. These little details are so easy to overlook, so tempting to brush off as unimportant. But add a number of seemingly minor details together, and you end up with something of far more value than you would without them.

It’s the little details that keep a customer coming back over and over, it’s the little details that cause a customer to rationalize paying more because she feels she is getting more, it’s the little details that keep people talking about you and recommending everyone they know to you.

Anyone can do the big things right; it’s the little things that differentiate one business from another and that influence customers to choose one over the other. Often, small-business owners cut out the little details when times get tough, and this is a big mistake.[40]

There is, however, no one-size-fits-all design for customer experience in the B2C market. Small businesses vary in terms of the size, industry, and nature of the business, so customer experience planning and design will necessarily differ in accordance with these factors. The customer experience for a 1-person business will be very different from an experience with a 400-employee company.

Customer Experience in the B2B Market

Talk to customer experience executives in a B2B environment about emotional engagement and you will see their eyes roll. Ask them if they would consider designing retail stores with customized smell and music to reinforce the customer experience and you will most likely be ushered out of their offices. Mention the iPod or MySpace experience and you will likely face a torrent of sighs and frowns. Lior Arussy[41]

Creating customer relationships in the B2B environment is radically different from the B2C environment because customers face different challenges, resources, and suppliers.[42] In the B2B world, there will almost always be “multiple people across multiple functions who play major roles in evaluating, selecting, managing, paying for and using the products and services their company buys…So, unlike the B2C company, if you are a B2B supplier there will be a host of individual ‘customers’ in engineering, purchasing, quality, manufacturing, etc. with different needs and expectations whose individual experiences you must address to make any given sale.”[43] This is offset, however, by the fact that a B2B company probably has a substantially smaller number of potential customers in a given target market, so it is often possible to actually get to know them personally. Smart B2B firms can tailor their products or services specifically to deliver the experiences wanted by people they know directly.[44]

Despite the challenges, customer experience is relevant in the B2B environment. However, because “the buy decision-making processes in most companies are typically fully structured and quantitative criteria-based…the explicitly emotional experience laden sales pitch that drives consumer buying is not a fit in the B2B world.”[45] The products that often represent B2B business’s sole value proposition are rarely emotionally engaging or visually appealing. Think bolts, wires, copy paper, shredding machines, bread for a restaurant, and machinery. How engaging can these items be?

There are touchpoints in B2B processes[46] before and after the sale (e.g., information gathering, website visits and inquiries, delivery of spare parts, service calls on machinery and office equipment, and telephone interactions) that can be identified and improved. However, the inherent differences between B2B and B2C environments must be clearly understood so that the B2C customer experience models do not become the paradigm for B2B customer experience designs. As is the case in the B2C market, there is no universal approach to customer experience in the B2B market. Small B2B companies also vary in terms of the products and the services offered and the size, industry, and nature of the business, so customer experience planning and design will necessarily differ in accordance with these factors.

The greatest challenge in delighting B2B customers is adding unique and differentiating value that solves customer problems. When defining the customer experience, recognize that this value should extend to the entire customer and business life cycle—presale engagement, the sales process, and postsale interactions. Experiences at every stage of the customer life cycle should be customized to each individual customer.[47]

Customer Loyalty

Customer loyalty is “all about attracting the right customers, getting them to buy, buy often, buy in higher quantities and bring [the business] even more customers.”[48] It involves an emotional commitment to a brand or a business (“We love doing business with your company.”), an attitude component (“I feel better about this brand or this business.”), and a behavior component (“I’ll keep buying this brand or patronizing that business, regardless.”). Attitudes are important because repeat purchases alone do not always mean that a customer is emotionally invested.[49] Think about the thrill of buying car insurance. We may keep buying from the same company, but we rarely have an emotional commitment to that company. Emotional commitment is key in customer loyalty.

The benefits of loyal customers are numerous:[50]

- They buy more and are often willing to pay more. This creates a steadier cash flow for a business.

- Loyal customers will refer other customers to a company, saving the marketing and advertising costs of acquiring customers.

- They are more forgiving when you make mistakes—even serious ones—especially if you have a system in place that empowers employees to correct errors on the spot. Then loyal customers become even more loyal.

- A loyal customer’s endorsement can outstrip the most extravagant marketing efforts. The word on the street is usually more powerful.

- Thriving companies with high customer loyalty usually have loyal employees who are genuinely engaged.

- Thriving companies with high customer and employee loyalty are generally known to outpace their competition in innovation.

- Loyal customers understand a company’s processes and can offer suggestions for improvement.

- An increase in customer retention can boost a company’s bottom-line profit by 25–100 percent, depending on fixed costs—costs that remain the same regardless of the amount of sales (e.g., rent).

Customer loyalty begins with the customer experience and is built over time through the collection of positive experiences.[51] This will be true no matter the size, industry, and nature of the small business. Customers’ experiences will influence how much they will buy, whether they switch to a competitor, and whether they will recommend the brand or the business to someone else.[52] Small businesses cannot rely on the loyalty that comes from convenience (e.g., using the car dealer close to home for repairs instead of the one farther away that provides better service). Loyalty is about making a customer feel special. This is the dream of all small businesses—which is something that small businesses are particularly well suited to create. Because of their size, it is easier for small businesses to have closer relationships with their customers, create a more personal shopping environment, and, in general, create great customer experiences. Think back to Bob Brown of the Cheshire Package Store (Chapter 2). He prides himself on the kind of shopping environment and customer relationships that lead to loyalty.

Grounds for Loyalty

How do people make choices about which pharmacy to go to? Paul Gauvreau decided to find out by asking customers why they were shopping in one particular store.

- “I shop here because it’s close to where I live.” (The convenience shopper.)

- “I like the pharmacist, I trust him/her.” (This customer has a good relationship with their pharmacist.)

- “The staff makes me feel like part of the family.”

- “I feel like they care about my health.”

- “The entire atmosphere in this store reminds me of home, where I felt welcome.”

- “I don’t feel like another number here or just another patient. They really care about me.”

Paul concluded that this pharmacy succeeded in differentiating itself from the competition in a unique way: by how they made their customers feel—and this is what will generate the most intimate loyalty in a customer.[53]

Key Takeaways

- The customer and the consumer are not necessarily the same person…but they can be.

- The customer and the consumer should be the focus of the marketing mix.

- B2C and B2B are the two types of customer markets. The B2B market dwarfs the B2C market in terms of sales.

- It is critical for a small business to understand its customers.

- Customer experience is a person’s entire interaction with a small business. It involves emotional connections to the business.

- There is no one-size-fits-all customer experience for a B2C or a B2B small business. The customer’s journey should be mapped and changes made to improve the experience.

- There are big differences between the customer experiences for B2C and B2B businesses.

- There are multiple benefits to customer loyalty. It is important to small business success. A positive customer experience drives loyalty.

Marketing Research

Not everyone can be like Steve Jobs of Apple. Jobs was famous for saying that he did not pay too much attention to customer research, particularly with respect to what customers say they want. Instead, he was very “adept at seeing under the surface of what customers want now; they just don’t realize it until they see it. This ability is best expressed by the German word ‘zeitgeist’—the emerging spirit of the age or mood of the moment. It probably best translates as market readiness or customer readiness. People like Jobs can see what the market is ready for before the market knows itself.”[54] Most small businesses will not find themselves in this enviable position. However, this does not mean that all small businesses take a methodical approach to studying the marketplace and their prospective as well as current consumers. Marketing research among small businesses ranges along a continuum from no research at all to the hiring of a professional research firm. Along the way, there will be both formal and informal approaches, the differences again being attributable to the size, industry, and nature of the business along with the personal predispositions of the small-business owners or managers. Nonetheless, it is important for small-business owners and managers to understand what marketing research is all about and how it can be helpful to their businesses. It is also important to understand that marketing research must take the cultures of different communities into consideration because the target market might not be the same—even in relatively close localities.

What Is Marketing Research?

Marketing research is about gathering the information that is needed to make decisions about a business. As an important precursor to the development of a marketing strategy, marketing research “involves the systematic design, collection, recording, analysis, interpretation, and reporting of information pertinent to a particular marketing decision facing a company.”[55] Marketing research is not a perfect science because much of it deals with people and their constantly changing feelings and behaviors—which are all influenced by countless subjective factors. What this means is that facts and opinions must be gathered in an orderly and objective way to find out what people want to buy, not just what the business wants to sell them.[56] It also means that information relevant to the market, the competition, and the marketing environment should be gathered and analyzed in an orderly and objective way.

Why Do It?

The simple truth is that a small business cannot sell products or services—at least not for long—if customers do not want to buy them. Consider the following true scenario:[57] A local small business that specialized in underground sprinkling systems and hot tubs for years decided to start selling go-carts. Not long after they introduced them, they had a fleet of go-carts lined up outside their business with a huge “Must go; prices slashed” banner over them. This was not a surprise to anyone else. Go-carts had nothing to do with their usual products, so why would their regular customers be interested in them? Also, a quick look at the demographics of the area would have revealed that the majority of the consumers in the retirement town were elderly. There would likely be little interest in go-carts. It is clear that the business owner would have benefitted from some marketing research.

Marketing research for small business offers many benefits. For example, companies can find hidden niches, design customer experiences, build customer loyalty, identify new business opportunities, design promotional materials, select channels of distribution, find out which customers are profitable and which are not, determine what areas of the company’s website are generating the most revenue, and identify market trends that are likely to have the greatest impact on the business. Answers can be found for the important questions that all small businesses face, such as the following:[58]

- How are market trends impacting my business?

- How does our target market make buying decisions?

- What is our market share and how can we increase it?

- How does customer satisfaction with our products or services measure up to that of the competition?

- How will our existing customers respond to a new product or service?

In many ways, small businesses have a marketing research advantage over large businesses. The small business is close to its customers and is able to learn much more quickly about their buying habits, what they like, and what they do not like. However, even though “small business owners have a sense [of] their customers’ needs from years of experience…this informal information may not be timely or relevant to the current market.”[59]

It therefore behooves a small business to think seriously in terms of a marketing research effort—even a very small one—that is more focused and structured. This will increase the chances that the results will be timely and will enable the small-business owner or manager “to reduce business risks, spot current and upcoming problems in the current market, identify sales opportunities, and develop plans of actions.”[60] The specific nature and extent of any marketing research effort will, however, be a function of the product, the size and nature of the business, the industry, and the small-business owner or manager. There is no approach that is right for all situations and all small businesses.

Types of Marketing Research

Small businesses can conduct primary or secondary marketing research or a combination of the two. Primary marketing research involves the collection of data for a specific purpose or project.[61] For example, asking existing customers why they purchase from the business and how they heard about it would be considered primary research. Another example would be conducting a study of specific competitors with respect to products and services offered and their price levels. These would be simple marketing research projects for a small business, either business-to-consumer (B2C) or business-to-business (B2B), and would not require the services of a professional research company. Such companies would be able to provide more sophisticated marketing research, but the cost might be too high for the many small businesses that are operating on a shoestring budget.

Data gathering techniques in primary marketing research can include observation, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, and focus groups. A focus group is six to ten people carefully selected by a researcher and brought together to discuss various aspects of interest at length.[62] Focus groups are not likely to be chosen by small businesses because they are costly. However, the other techniques would be well within the means of most small businesses—and each can be conducted online (except for observation), by mail, in person, or by telephone. SurveyMonkey is a popular and very inexpensive online survey provider. Its available plans run from free to less than $20 per month for unlimited questions and unlimited responses. They also provide excellent tutorials. SurveyMonkey, used by many large companies, would be an excellent choice for any small business.

Secondary marketing research is based on information that has already been gathered and published. Some of the information may be free—as in the case of the US Census, public library databases and collections, certain websites, company information, and some trade associations to which the company belongs—or it can be bought. Purchased sources of information (not an exhaustive list) include newspapers,[63] magazines, trade association reports, and proprietary research reports (i.e., reports from organizations that conduct original research and then sell it). eMarketer is a company that provides excellent marketing articles for free but also sells its more comprehensive reports. The reports are excellent, providing analysis and in-depth data that cannot be found elsewhere, but they are pricey.

If a small business was looking to introduce a new product to an entirely different market, secondary research could be conducted to find out where customer prospects live and whether the potential market is big enough to make the investment in the new product worthwhile.[64] Secondary research would also be appropriate when looking for things such as economic trends, online consumer purchasing habits, and competitor identification.

Types of Marketing Research

| Primary Marketing Research | Secondary Marketing Research |

|---|---|

| Data for a specific purpose or for a specific project | Information that has already been gathered and published |

| Tends to be more expensive | Tends to be lower cost |

| Customized to meet a company’s needs | May not meet a company’s needs |

| Fresh, new data | Data are frequently outdated (e.g., using US 2000 census data in 2011) |

| Proprietary—no one else has it | Available to competitors |

| Examples: in-person surveys, customer comments, observation, and SurveyMonkey online survey | Examples: Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg BusinessWeek, US Census 2010, Bureau of Labor Statistics |

Source in footnotes[65]

The Marketing Research Process

Most small-business owners do marketing research every day—without being aware of it. They analyze returned items, ask former customers why they switched to another company, and look at a competitor’s prices. Formal marketing research simply makes this familiar process orderly by providing the appropriate framework.[66] Effective marketing research follows the following six steps:[67]

- Define the problem and the research objectives. Care must be taken not to define the problem too broadly or too narrowly—and not to identify a symptom as the problem. The research objectives should flow from the problem definition.

- Develop the research plan. This is a plan for gathering the needed information, part of which will include cost. Also to be determined is the following: whether primary research, secondary research, or some combination of the two will be used. The specific techniques will be identified, and a timetable will be established.

- Collect the information. This phase is typically the most expensive and the most error prone.

- Analyze the information. Analysis involves extracting meaning from the raw data. It can involve simple tabulations or very sophisticated statistical techniques. The objective is to convert the raw data into actionable information.

- Present the findings. The findings are presented to the decision maker(s). In many small businesses, the owner or the manager may conduct the research, so the findings are presented in a format that will make sense for the owner and other members of the decision-making team.

- Make the decision. The owner or manager must consider the information and decide how to act on it. One possible result is that the information gathered is not sufficient for making a decision. The problem may be a flawed marketing research process or problems obtaining access to appropriate data. The question becomes whether the situation is important enough to warrant additional research.

What Does It Cost?

A popular approach with small-business owners is to allocate a small percentage of gross sales for the most recent year for marketing research. This usually amounts to about 2 percent for an existing business. It has been suggested, however, that as much as 10 percent of gross sales should be allocated to marketing research if the business is planning to launch a new product.[68]

There are several things that small businesses can do to keep the costs down. They can do the research on their own; work with local colleges and universities to engage business students in research projects; conduct online surveys using companies such as SurveyMonkey; and create an online community with forums, blogs, and chat sessions that reveal customers’ experiences with a company’s product or the perception of a company’s brand.[69] The latter two options, of course, presume the existence of an e-commerce operation. Even given the inexpensive options that are available, however, hiring a professional research firm can be worth the price. The specific marketing research choice(s) made will depend, as always, on the size and the nature of the business, the industry, and the individual B2C or B2B small-business owner or manager.

When Should Marketing Research Be Done?

There is no precise answer to this question. As a general rule, marketing research should be done when important marketing decisions must be made. It should be done at times when customers may be easily accessible (e.g., a gift shop may want to conduct research before the holiday season when customers are more likely to be thinking about buying gifts for friends and loved ones), when you are thinking about adding a new product or service to the business, or when a competitor seems to be taking away market share. The trick, though, “is not to wait very long, because your competitors can start getting the answers before you do.”[70]

Common Marketing Research Mistakes

Before deciding on a marketing research path, it is important for a small-business owner or manager to be aware of the following common pitfalls that small businesses encounter:[71]

- Thinking the research will cost too much. Small businesses definitely face a challenge to afford the costs of marketing research. However, marketing research costs range from free to several thousands of dollars.

- Using only secondary research. The published work of others is a great place to start, but it is often outdated and provides only broad knowledge. More specific knowledge can be obtained from purchasing proprietary reports, but this can be pricey, and the focus may not be quite right. Primary research should also be considered.

- Using only web resources. Data available on the Internet are available to everyone who can find it. It may not be fully accurate, and its accuracy may be difficult to evaluate. Deeper searches can be conducted at the local library, college campus, or small business center.

- Surveying only the people you know. This will not get you the most useful, accurate, and objective information. You must talk to actual customers to find out about their needs, wants, and expectations.

- Hitting a wall. Any research project has its ups and downs. It is easy to lose motivation and shorten the project. Persistence must be maintained because it will all come together in the end. It is important to talk to actual or potential customers early.

Key Takeaways

- Many small businesses do not conduct any marketing research.

- Marketing research is about gathering the information that is needed to make decisions about the business.

- Marketing research is important because businesses cannot sell products or services that people do not want to buy.

- Small businesses can conduct primary or secondary research or a combination of the two. They can also buy proprietary reports that have been prepared by other companies.

- It is common for small businesses to allocate 2 percent of their gross sales to marketing research. Several things can be done to keep marketing research costs down.

- Marketing research should be done when key decisions must be made.

- Small-business owners should be aware of several common marketing research pitfalls that small businesses encounter.

- Jack Trout, “Peter Drucker on Marketing,” Forbes, July 3, 2006, accessed January 19, 2012, www.forbes.com/2006/06/30/jack-trout-on-marketing-cx_jt_0703drucker .html. ↵

- “AMA Definition of Marketing,” American Marketing Association, December 17, 2007, accessed December 1, 2011, www.marketingpower.com/Community/ARC/Pages/Additional/Definition/default.aspx. ↵

- Adapted from Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 6–7. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 19. ↵

- Rohit Deshpande and John U. Farley, “Measuring Market Orientation: Generalization and Synthesis,” Journal of Market-Focused Management 2 (1998): 213–32; Ajay K. Kohli and Bernard J. Jaworski, “Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications,” Journal of Marketing 54 (1990): 1–18; and John C. Narver and Stanley F. Slater, “The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability,” Journal of Marketing 54 (1990): 20–35—all as cited in Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 19. ↵

- Charles W. Lamb, Joseph F. Hair, and Carl McDaniel, Essentials of Marketing (Mason, OH: South-Western, 2004), 8. ↵

- “You Don’t Say?,” Sales and Marketing Management, October 1994, 111–12. ↵

- Dana-Nicoleta Lascu and Kenneth E. Clow, Essentials of Marketing (Mason, OH: Atomic Dog Publishing, 2007), 12. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 19. ↵

- Charles S. Mack, “Holistic Marketing,” Association Management, February 1, 1999, accessed January 19, 2012, www.asaecenter.org/Resources/AMMagArticleDetail.cfm?ItemNumber=880. ↵

- Center for Business Planning, “Market Segmentation,” Business Resource Software, Inc., accessed December 1, 2011, www.businessplans.org/segment.html. ↵

- Adapted from “Market Segmentation,” Business Resource Software, Inc., accessed December 2, 2011, http://www.businessplans.org/segment.html; adapted from Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 214, 227. ↵

- Rick Suttle, “Define Market Segmentation & Targeting,” Chron.com, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbusiness.chron.com/define-market-segmentation-targeting-3253 .html. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 401. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 294–95. ↵

- Dana-Nicoleta Lascu and Kenneth E. Clow, Essentials of Marketing (Mason, OH: Atomic Dog Publishing, 2007), 170. ↵

- “History of Ivory Soap,” Essortment.com, accessed December 1, 2011, www.essortment.com/history-ivory-soap-21051.html. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 182. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 182. ↵

- Adapted from Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 155. ↵

- Dana-Nicoleta Lascu and Kenneth E. Clow, Essentials of Marketing (Mason, OH: Atomic Dog Publishing, 2007), 112. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 168; Dana-Nicoleta Lascu and Kenneth E. Clow, Essentials of Marketing (Mason, OH: Atomic Dog Publishing, 2007), 112–17. ↵

- Dana-Nicoleta Lascu and Kenneth E. Clow, Essentials of Marketing (Mason, OH: Atomic Dog Publishing, 2007), 137. ↵

- Bill Furlong, “How the Internet Is Transforming B2B Marketing,” BrandNewBusinesses.com, accessed December 1, 2011, www.brandnewbusinesses.com/NewsletterAugust2008A1.aspx. ↵

- Frederick E. Webster Jr. and Yoram Wind, Organizational Buying Behavior (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1972), 2, as cited in Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 188. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 188; Dana-Nicoleta Lascu and Kenneth E. Clow, Essentials of Marketing (Mason, OH: Atomic Dog Publishing, 2007), 139. ↵

- Adapted from Dana-Nicoleta Lascu and Kenneth E. Clow, Essentials of Marketing (Mason, OH: Atomic Dog Publishing, 2007), 148–55. ↵

- Jeneanne Rae, “The Importance of Great Customer Experiences…And the Best Ways to Deliver Them,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, November 27, 2006, accessed December 1, 2011, www.BusinessWeek.com/magazine/content/06_48/b4011429.htm?chan =search. ↵

- Fran ONeal, “‘Customer Experience’ for Small Business: When Does It Start?,” Small Business Growing, August 23, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbusinessgrowing.com/2010/08/23/what-is-the-customer-experience-for-small -business. ↵

- Eric Brown, “Engage Emotion and Shape the Customer Experience,” Small Business Answers, December 14, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, www.smallbusinessanswers.com/eric-brown/engage-emotion-and-shape-the -customer-ex.php. ↵

- Harley Manning, “Customer Experience Defined,” Forrester’s Blogs, November 23, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, blogs.forrester.com/harley_manning ?page=1&10-11-23-customer_experience_defined=. ↵

- Harley Manning, “Customer Experience Defined,” Forrester’s Blogs, November 23, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, blogs.forrester.com/harley_manning ?page=1&10-11-23-customer_experience_defined=. ↵

- Lynn Hunsaker, Innovating Superior Customer Experience (Sunnyvale, CA: ClearAction, 2009), e-book, accessed December 1, 2011, www.clearaction.biz/innovation. ↵

- “Grow Customers and Referrals!” Small Business Growing, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbusinessgrowing.com/grow-customers-and-referrals. ↵

- Colin Shaw, “Engage Your Customers Emotionally to Create Advocates,” CustomerThink, September 17, 2007, accessed December 1, 2011, www.customerthink.com/article/engage_your_customers_emotionally. ↵

- Jeneanne Rae, “The Importance of Great Customer Experiences…And the Best Ways to Deliver Them,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, November 27, 2006, accessed December 1, 2011, www.BusinessWeek.com/magazine/content/06_48/b4011429.htm?chan =search. ↵

- Shaun Smith, “When Is a Store Not a Store—The Next Stage of the Retail Customer Experience,” shaunsmith+co Ltd, March 29, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, www.smithcoconsultancy.com/2010/03/when-is-a-store-not-a-store-%E2%80%93 -the-next-stage-of-the-retail-customer-experience. ↵

- Colin Shaw, “Engage Your Customers Emotionally to Create Advocates,” CustomerThink, September 17, 2007, accessed December 1, 2011, www.customerthink.com/article/engage_your_customers_emotionally. ↵

- Jeneanne Rae, “The Importance of Great Customer Experiences…And the Best Ways to Deliver Them,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, November 27, 2006, accessed December 1, 2011, www.BusinessWeek.com/magazine/content/06_48/b4011429.htm?chan =search. ↵

- Sydney Barrows, “6 Ways to Create a Memorable Customer Experience,” Entrepreneur, May 19, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, www.entrepreneur.com/article/206760. ↵

- Lior Arussy, “Creating Customer Experience in B2B Relationships: Managing ‘Multiple Customers’ Is the Key,” G-CEM, accessed December 28, 2011, www.g-cem.org/eng/content_details.jsp?contentid=2203&subjectid=107. ↵

- Lior Arussy, “Creating Customer Experience in B2B Relationships: Managing ‘Multiple Customers’ Is the Key,” G-CEM, accessed December 28, 2011, www.g-cem.org/eng/content_details.jsp?contentid=2203&subjectid=107. ↵

- Richard Tait, “What’s Different about the B2B Customer Experience,” Winning Customer Experiences, August 16, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, winningcustomerexperiences.wordpress.com/2010/08/16/whats-different-about -the-b2b-customer-experience. ↵

- Richard Tait, “What’s Different about the B2B Customer Experience,” Winning Customer Experiences, August 16, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, winningcustomerexperiences.wordpress.com/2010/08/16/whats-different-about -the-b2b-customer-experience. ↵

- Richard Tait, “What’s Different about the B2B Customer Experience,” Winning Customer Experiences, August 16, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, winningcustomerexperiences.wordpress.com/2010/08/16/whats-different-about -the-b2b-customer-experience. ↵

- adapted from Pawan Singh, “The 9 Drivers of B2B Customer Centricity,” Destination CRM.com, December 11, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, www.destinationcrm.com/Articles/Web-Exclusives/Viewpoints/The-9-Drivers-of -B2B-Customer-Centricity-72672.aspx. ↵

- Lior Arussy, “Creating Customer Experience in B2B Relationships: Managing ‘Multiple Customers’ Is the Key,” G-CEM, accessed December 28, 2011, www.g-cem.org/eng/content_details.jsp?contentid=2203&subjectid=107. ↵

- “What Is Customer Loyalty?,” Customer Loyalty Institute, accessed December 1, 2011, www.customerloyalty.org/what-is-customer-loyalty. ↵

- Adapted from “Why Measure—What Is Loyalty?,” Mindshare Technologies, accessed December 1, 2011, www.mshare.net/why/what-is-loyalty.html. ↵

- Adapted from Rama Ramaswami, “Eight Reasons to Keep Your Customers Loyal,” Multichannel Merchant, January 12, 2005, accessed December 1, 2011, multichannelmerchant.com/opsandfulfillment/advisor/Brandi-custloyal/. ↵

- Jeffrey Gangemi, “Customer Loyalty: Dos and Don’ts,” BusinessWeek, June 29, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, www.BusinessWeek.com/smallbiz/tipsheet/06/29.htm. ↵

- Bruce Temkin, “The Four Customer Experience Core Competencies,” Temkin Group, June 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, experiencematters.files.wordpress.com/2010/06/1006_thefourcustomerexperiencecorecompetencies_v2.pdf. ↵

- Paul Gauvreau, “Making Customers Feel Special Brings Loyalty,” Pharmacy Post 11, no. 10 (2003): 40. ↵

- Shaun Smith, “Why Steve Jobs Doesn’t Listen to Customers,” Customer Think, February 8, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, www.customerthink.com/blog/why_steve_jobs_doesnt_listen_to_customers. ↵

- Dana-Nicoleta Lascu and Kenneth E. Clow, Essentials of Marketing (Mason, Ohio: Atomic Dog Publishing, 2007), 191. ↵

- “Market Research Basics,” SmallBusiness.com, October 26, 2009, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbusiness.com/wiki/Market_research_basics. ↵

- Susan Ward, “Do-It-Yourself Market Research—Part 1: You Need Market Research,” About.com, accessed December 1, 2011, sbinfocanada.about.com/cs/marketing/a/marketresearch.htm. ↵

- Jesse Hopps, “Market Research Best Practices,” EvanCarmichael.com, accessed December 1, 2011, www.evancarmichael.com/Marketing/5604/Market-Research -Best-Practices.html; adapted from Joy Levin, “How Marketing Research Can Benefit a Small Business,” Small Business Trends, January 26, 2006, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbiztrends.com/2006/01/how-marketing-research-can-benefit-a-small -business.html. ↵

- “Market Research Basics,” SmallBusiness.com, October 26, 2009, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbusiness.com/wiki/Market_research_basics. ↵

- “Market Research Basics,” SmallBusiness.com, October 26, 2009, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbusiness.com/wiki/Market_research_basics. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 91. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2009), 93. ↵

- Patricia Faulhaber, “Today’s Headlines Provide Market Research,” Marketing and PR @ Suite101, May 14, 2009, accessed December 1, 2011, patricia-faulhaber.suite101.com/todays-healines-provide-market-research-a117653. ↵

- Joy Levin, “How Marketing Research Can Benefit a Small Business,” Small Business Trends, January 26, 2006, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbiztrends.com/2006/01/how-marketing-research-can-benefit-a-small-business.html. ↵

- Adapted from Marcella Kelly and Jim McGowen, BUSN (Mason, OH: South-Western, 2008), 147. ↵

- “Market Research Basics,” SmallBusiness.com, October 26, 2009, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbusiness.com/wiki/Market_research_basics. ↵

- Adapted from Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 91–103. ↵

- “Market Research Basics,” SmallBusiness.com, October 26, 2009, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbusiness.com/wiki/Market_research_basics. ↵

- John Tozzi, “Market Research on the Cheap,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, January 9, 2008, accessed December 1, 2011, www.BusinessWeek.com/smallbiz/content/jan2008/sb2008019_352779.htm. ↵

- Joy Levin, “How Marketing Research Can Benefit a Small Business,” Small Business Trends, January 26, 2006, accessed December 1, 2011, smallbiztrends.com/2006/01/how-marketing-research-can-benefit-a-small-business.html. ↵

- Darrell Zahorsky, “6 Common Market Research Mistakes of Small Business,” About.com, accessed December 1, 2011, sbinformation.about.com/od/marketresearch/a/marketresearch.htm; Lesley Spencer Pyle, “How to Do Market Research—The Basics,” Entrepreneur, September 23, 2010, accessed December 1, 2011, www.entrepreneur.com/article/217345. ↵

The activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large. It is a unique, distinguishing function of a business.

The focus of all company operations should be meeting the customer’s needs and wants in ways that distinguish a company from its competition but yet allow a company to meet organizational objectives and achieve profitability.

A company will have an advantage over its competitors if it applies the marketing concept in a manner that maximizes society’s well-being, which requires balancing customer satisfaction, company profits, and the long-term welfare of society.

A business practice that contributes to protecting the environment.

Developing, designing, and implementing marketing programs, processes, and activities that recognize breadth and interdependence.

The difference between the benefits a customer receives from a product or a service and the costs associated with obtaining the product or the service.

A basis of value that relates to a product’s or a service’s ability to perform its utilitarian purpose.

A basis of value that involves a sense of relationship with other groups by using images or symbols.

A basis of value that is derived from the ability to evoke an emotional or an affective response.

A basis of value that is generated by a sense of novelty or simple fun.

A basis of value that is derived from a particular context or a sociocultural setting.

Dividing the market into several portions that are different from each other. It involves recognizing that the market at large is not homogeneous.

One or more segments that have been chosen as the focus for business operations.

A small, more narrowly defined market that is not being served well or at all by mainstream product or service marketers.

The combination of product, price, promotion, and place (distribution).

Different prices are charged depending on where a customer purchases a product.

Different prices for different groups.

People talk to each other about their experiences with goods and services.

The factors that affect a small business.

A company’s existing products and strategies; culture; strengths and weaknesses; internal resources; capabilities with respect to marketing, manufacturing, and distribution; and relationships with stakeholders.

Social factors, demographics, economic environment, political and legal factors, technology, competition, and ethics.

Selecting one or more target markets, making differentiation and positioning decisions, and creating and maintaining a marketing mix—all within the context of marketing objectives.

A firm provides products or services that meet customer value in some unique way.

Placing the brand (whether store, product, or service) in the consumer’s mind in relation to other competing products, based on product traits and benefits that are relevant to the consumer.

The person or the business that actually buys a product or a service.

The person or the company that uses or consumes a product.

Sales among other businesses or organizations.

Retail sales among businesses and individual consumers.

How individuals, groups, and organizations select, buy, use, and dispose of goods, services, ideas, or experiences to satisfy their needs and wants.

Age, gender, race, ethnicity, occupation, income, and life-cycle stage.

Culture, subculture, social class, family, and reference groups.

Motivation, perception, learning, attitudes, personality, and self-concept.

The reason for purchase, the time we have available to shop and buy, our mood, and the shopping environment.

Where an individual is with respect to passage through the different phases of life (e.g., single, married without children, empty nester, and widow or widower).

A group that has a direct or indirect influence on a person’s attitudes and behavior.

How each person sees, hears, touches, and smells and then interprets the world around him or her.