1 Chapter 1 – Foundations of Small Business

Small Business in the U.S. Economy

In 2006, Thomas M. Sullivan, the chief counsel for advocacy of the Small Business Administration (SBA), said, “Small business is a major part of our economy…small businesses innovate and create new jobs at a faster rate than their larger competitors. They are nimble, creative, and a vital part of every community across the country.”[1]

This text is devoted to small business, not entrepreneurship. There has always been a challenge to distinguish—correctly—between the small business owner and the entrepreneur. Some argue that there is no difference between the two terms. The word entrepreneur is derived from a French word for “to undertake,” which might indicate that entrepreneurs should be identified as those who start businesses. That is not the focus of this text. We will instead focus on running a small business.

Small Business Defined

The Small Business Administration (SBA) definition of a small business has evolved over time and is dependent on the particular industry. In the 1950s, the SBA defined a small business firm as “independently owned and operated…and not dominant in its field of operation.”[2] This is still part of their definition. At that time, the SBA classified a small firm as being limited to 250 employees for industrial organizations. Currently, this definition depends on the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) for a business. The SBA recognizes that there are significant differences, across industries, with respect to competitiveness, entry and exit costs, distribution by size, growth rates, and technological change. Although the SBA defines 500 employees as the limit for the majority of industrial firms and receipts of $7 million for the majority of service, retail, and construction firms, there are different values for some industries.

The SBA definition of what constitutes a small business has practical significance. Small businesses have access to an extensive support network provided by the SBA. It runs the SCORE program, which has more than 12,000 volunteers who assist small firms with counseling and training. The SBA also operates Small Business Development Centers, Export Assistance Centers, and Women’s Business Centers. These centers provide comprehensive assistance to small firms. There can be significant economic support for small firms from the SBA. It offers a variety of guaranteed loan programs to start-ups and small firms. It assists small firms in acquiring access to nearly half a trillion dollars in federal contracts. In fact, legislation attempts to target 23 percent of this value for small firms. The SBA can also assist with financial aid following a disaster.

GDP

In 1958, small businesses contributed 57 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). This value dropped to 50 percent by 1980. What is remarkable is that this 50 percent figure has essentially held steady for the last thirty years.[3]

Size

Few people realize that the overwhelming majority of businesses in the United States are small businesses with fewer than five hundred employees. The SBA puts the number of small businesses at 99.7 percent of the total number of businesses in the United States. However, most of the businesses are nonemployee businesses (i.e., no paid employees) and are home-based.

Innovation and Competitiveness

One area where the public has a better understanding of the strength of small business is in the area of innovation. Evidence dating back to the 1970s indicates that small businesses disproportionately produce innovations.[4] It has been estimated that 40 percent of America’s scientific and engineering talent is employed by small businesses. The same study found that small businesses that pursue patents produce thirteen to fourteen times as many patents per employee as their larger counterparts. Further, it has been found that these patents are twice as likely to be in the top 1 percent of highest impact patents.[5]

Small Business Advantages

It is possible that small size might pose an advantage with respect to being more innovative. The reasons for this have been attributed to several factors:

- Passion. Small-business owners are interested in making businesses successful and are more open to new concepts and ideas to achieve that end.

- Customer connection. Being small, these firms better know their customers’ needs and therefore are better positioned to meet them.

- Agility. Being small, these firms can adapt more readily to changing environment.

- Willingness to experiment. Small-business owners are willing to risk failure on some experiments.

- Resource limitation. Having fewer resources, small businesses become adept at doing more with less.

- Information sharing. Smaller size may mean that there is a tighter social network for sharing ideas.[6]

Regardless of the reasons, small businesses, particularly in high-tech industries, play a critical role in preserving American global competitiveness.

Small Business and National Employment

The majority—approximately 50.2 percent in 2006—of private sector employees work for small businesses. For 2006, slightly more than 18 percent of the entire private sector workforce was employed by firms with fewer than twenty employees. It is interesting to note that there can be significant difference in the percentage of employment by small business across states. Although the national average was 50.2 percent in 2006, the state with the lowest percentage working for small businesses was Florida with 44.0 percent, while the state with the highest percentage was Montana with a remarkable 69.8 percent.[7]

Percentage of Private Sector Employees by Firm Size

| Year | 0–4 Employees | 5–9 Employees | 10–19 Employees | 20–99 Employees | 100–499 Employees | 500 Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | 5.70% | 6.90%% | 8.26% | 19.16% | 14.53% | 45.45% |

| 1991 | 5.58% | 6.69% | 8.00% | 18.58% | 14.24% | 46.91% |

| 1994 | 5.50% | 6.55% | 7.80% | 18.29% | 14.60% | 47.26% |

| 1997 | 5.20% | 4.95% | 6.36% | 16.23% | 13.73% | 53.54% |

| 2000 | 4.90% | 5.88% | 7.26% | 17.78% | 14.26% | 49.92% |

| 2003 | 5.09% | 5.94% | 7.35% | 17.80% | 14.49% | 49.34% |

| 2006 | 4.97% | 5.82% | 7.24% | 17.58% | 14.62% | 49.78% |

Source in the footnotes[8]

Job Creation

Small business is the great generator of jobs. Recent data indicate that small businesses produced 64 percent of the net new jobs from 1993 to the third quarter of 2008.[9] This is not a recent phenomenon. Thirty years of research studies have consistently indicated that the driving force in fostering new job creation is the birth of new companies and the net additions coming from small businesses. In the 1990s, firms with fewer than twenty employees produced far more net jobs proportionally to their size, and two to three times as many jobs were created through new business formation than through job expansion in small businesses.[10] The US Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics data confirm that the greatest number of new jobs comes from the creation of new businesses.

One last area concerning the small business contribution to American employment is its role with respect to minority ownership and employment. During the last decade, there has been a remarkable increase in the number of self-employed individuals. From 2000 to 2007, the number of women who were self-employed increased by 9.7 percent. The number of African Americans who were self-employed increased by 36.6 percent for the same time range. However, the most remarkable number was an increase of nearly 110 percent for Hispanics. It is clear that small business has become an increasingly attractive option for minority groups.[11] Women and Hispanics are also employed by small businesses at a higher rate than the national average.

Key Takeaways

- Small businesses have always played a key role in the US economy.

- Small businesses are responsible for more than half the employment in the United States.

- Small businesses have a prominent role in innovation and minority employment.

Success and Failure in Small Businesses

There are no easy answers to questions about success and failure in a small business. Why? Because the definition of “success” and “failure” is subjective. For instance, “success” could be:

- An artisan whose intrinsic satisfaction comes from performing the business activity

- The entrepreneur who seeks growth

- The owner who seeks independence.[12]

Success

Ask the average person what the purpose of a business is or how he or she would define a successful business, and the most likely response would be “one that makes a profit.” A more sophisticated reply might extend that to “one that makes an acceptable profit now and in the future.” Ask anyone in the finance department of a publicly held firm, and his or her answer would be “one that maximizes shareholder wealth.” The management guru Peter Drucker said that for businesses to succeed, they needed to create customers, while W. E. Deming, the quality guru, advocated that business success required “delighting” customers. No one can argue, specifically, with any of these definitions of small business success, but they miss an important element of the definition of success for the small business owner: to be free and independent.

Many people have studied whether there is any significant difference between the small business owner and the entrepreneur. Some entrepreneurs place more emphasis on growth in their definition of success.[13] However, it is clear that entrepreneurs and small business owners define much of their personal and their firm’s success in the context of providing them with independence. For many small business owners, being in charge of their own life is the prime motivator: a “fervently guarded sense of independence,” and money is seen as a beneficial by-product.[14] Oftentimes, financial performance is seen as an important measure of success. However, small businesses are reluctant to report their financial information, so this will always be an imperfect and incomplete measure of success.[15]

Failure

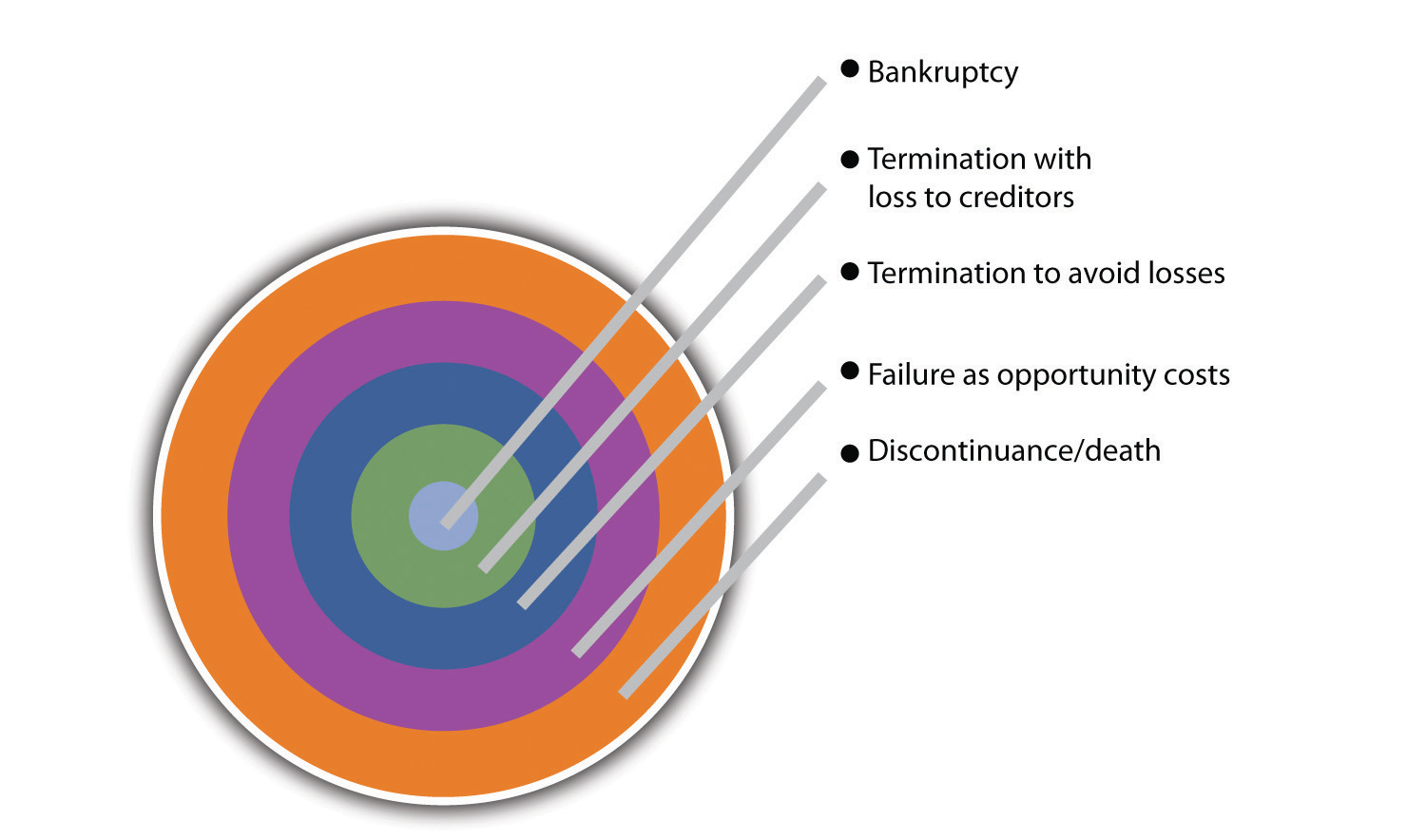

The term failure can have several meanings.[17]is often measured by the cessation of a firm’s operation, but this can be brought about by several things:

- An owner can die or simply choose to discontinue operations.

- The owner may recognize that the business is not generating sufficient return to warrant the effort that is being put into it. This is sometimes referred to as the failure of opportunity cost.

- A firm that is losing money may be terminated to avoid losses to its creditors.

- There can be losses to creditors that bring about cessations of the firm’s operations.

- The firm can experience bankruptcy. Bankruptcy is probably what most people think of when they hear the term business failure. However, the evidence indicates that bankruptcies constitute only a minor reason for failure.

Failure can therefore be thought of in terms of a cascading series of outcomes (see “Types of Business Failures”). There are even times when small business owners involved in a closure consider the firm successful at its closing. [18] Then there is the complication of considering the industry of the small business when examining failure and bankruptcy. The rates of failure can vary considerably across different industries; in the fourth quarter of 2009, the failure rates for service firms were half that of transportation firms.[19]

Types of Business Failures

The second issue associated with small business failure is a consideration of the time horizon. Again, there are wildly different viewpoints. The Dan River Small Business Development Center presented data that indicated that 95 percent of small businesses fail within five years.[20] Dun and Bradstreet reported that companies with fewer than twenty employees have only a 37 percent chance of surviving four years, but only 10 percent will go bankrupt.[21] The US Bureau of Labor Statistics indicated that 66 percent of new establishments survive for two years, and that number drops to 44 percent two years later.[22] It appears that the longer you survive, the higher the probability of your continued existence. This makes sense, but it is no guarantee. Any business can fail after many years of success.

Why Do Small Businesses Fail?

There is no more puzzling or better-studied issue in the field of small business than what causes them to fail. Given the critical role of small businesses in the US economy, the economic consequences of failure can be significant. Yet there is no definitive answer to the question.

Three broad categories of causes of failure have been identified: managerial inadequacy, financial inadequacy, and external factors. The first cause, managerial inadequacy, is the most frequently mentioned reason for firm failure.[23] Unfortunately, it is an all-inclusive explanation, much like explaining that all plane crashes are due to pilot failure. Over thirty years ago, it was observed that “while everyone agrees that bad management is the prime cause of failure, no one agrees what ‘bad management’ means nor how it can be recognized except that the company has collapsed—then everyone agrees that how badly managed it was.”[24] This observation remains true today.

The second most common explanation cites financial inadequacy or a lack of financial strength in a firm. A third set of explanations center on environmental or external factors, such as a significant decline in the economy.

Because it is important that small firms succeed, not fail, each factor will be discussed in detail. However, these factors are not independent elements distinct from each other. A declining economy will depress a firm’s sales, which negatively affects a firm’s cash flow. An owner who lacks the knowledge and experience to manage this cash flow problem will see his or her firm fail.

Managerial inadequacy is generally perceived as the major cause of small business failure. Unfortunately, this term encompasses a very broad set of issues. It has been estimated that two-thirds of small business failures are due to the incompetence of the owner-manager.[25] The identified problems cover behavioral issues, a lack of business skills, a lack of specific technical skills, and marketing myopia. Specifying every limitation of these owners would be prohibitive. However, some limitations are mentioned with remarkable consistency. Having poor communication skills, with employees and/or customers, appears to be a marker for failure.[26] The inability to listen to criticism or divergent views is a marker for failure, as is the inability to be flexible in one’s thinking.[27]

Ask many small business owners where their strategic plans exist, and they may point to their foreheads. The failure to conduct formal planning may be the most frequently mentioned item with respect to small business failure. Given the relative lack of resources, it is not surprising that small firms tend to opt for intuitive approaches to planning.[28] Formal approaches to planning are seen as a waste of time,[29] or they are seen as too theoretical. [30] The end result is that many small business owners fail to conduct formal strategic planning in a meaningful way.[31] In fact, many fail to conduct any planning; [32] others may fail to conduct operational planning, such as marketing strategies.[33] The evidence appears to clearly indicate that a small firm that wishes to be successful needs to not only develop an initial strategic plan but also conduct an ongoing process of strategic renewal through planning.

Many managers do not have the ability to correctly select staff or manage them.[34] Other managerial failings appear to be in limitations in the functional area of marketing. Failing firms tend to ignore the changing demands of their customers, something that can have devastating effects.[35] The failure to understand what customers value and being able to adapt to changing customer needs often leads to business failure.[36]

The second major cause of small business failure is finance. Financial problems fall into three categories: start-up, cash flow, and financial management. When a firm begins operation (start-up), it will require capital. Unfortunately, many small business owners initially underestimate the amount of capital that should be available for operations.[37] This may explain why most small firms that fail do so within the first few years of their creation. The failure to start with sufficient capital can be attributed to the inability of the owner to acquire the needed capital. It can also be due to the owner’s failure to sufficiently plan for his or her capital needs. Here we see the possible interactions among the major causes of firm failure. Cash-flow management has been identified as a prime cause for failure.[38] Good cash-flow management is essential for the survival of any firm, but small firms, in particular, must pay close attention to this process. Small businesses must develop and maintain effective financial controls, such as credit controls.[39] For very small businesses, this translates into having an owner who has at least a fundamental familiarity with accounting and finance.[40] In addition, the small firm will need either an in-house or an outsourced accountant.[41] Unfortunately, many owners fail to fully use their accountants’ advice to manage their businesses.[42]

The last major factor identified with the failure of small businesses is the external environment. There is a potentially infinite list of causes, but the economic environment tends to be most prominent. Here again, however, confusing appears to describe the list. Some argue that economic conditions contribute to between 30 percent and 50 percent of small business failures, in direct contradiction to the belief that managerial incompetence is the major cause.[43] Two economic measures appear to affect failure rates: interest rates, which appear to be tied to bankruptcies, and the unemployment rate, which appears to be tied to discontinuance.[44] The potential impact of these external economic variables might be that small business owners need to be either planner to cover potential contingencies or lucky.

Even given the confusing and sometimes conflicting results with respect to failure in small businesses, some common themes can be identified. The reasons for failure fall into three broad categories: managerial inadequacy, finance, and environmental. They, in turn, have some consistently mentioned factors (see table below). These factors should be viewed as warning signs—danger areas that need to be avoided if you wish to survive. Although small business owners cannot directly affect environmental conditions, they can recognize the potential problems that they might bring. This text will provide guidance on how the small business owner can minimize these threats through proactive leadership.

Reasons for Small Business Failure

| Managerial Inadequacy | Financial Inadequacy | External Factors |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Ultimately, business failure will be a company-specific combination of factors. Monitor101, a company that developed an Internet information monitoring product for institutional investors in 2005, failed badly. One of the cofounders identified the following seven mistakes that were made, most of which can be linked to managerial inadequacy:[45]

- The lack of a single “the buck stops here” leader until too late in the game

- No separation between the technology organization and the product organization

- Too much public relations, too early

- Too much money

- Not close enough to the customer

- Slowness to adapt to market reality

- Disagreement on strategy within the company and with the board

Key Takeaways

- There is no universal definition for small business success. However, many small business owners see success as their own independence.

- The failure rates for small businesses are wide ranging. There is no consensus.

- Three broad categories of factors are thought to contribute to small business failure: managerial inadequacy, financial inadequacy, and external forces, most notably the economic environment.

Evolution of a Small Business

Small businesses come in all shapes and sizes. One thing that they all share, however, is experience with common problems that arise at similar stages in their growth and organizational evolution. Predictable patterns can be seen. These patterns “tend to be sequential, occur as a hierarchical progression that is not easily reversed, and involve a broad range of organizational activities and structures.”[46] The industry life cycle adds further complications. The success of any small business will depend on its ability to adapt to evolutionary changes, each of which will be characterized by different requirements, opportunities, challenges, risks, and internal and external threats. The decisions that need to be made and the priorities that are established will differ through this evolution.

Stages of Growth

Understanding the small business growth stages can be invaluable as a framework for anticipating resource needs and problems, assessing risk, and formulating business strategies (e.g., evaluating and responding to the impact of a new tax). However, the growth stages will not be applicable to all small businesses because not all small businesses will be looking to grow. Business success is commonly associated with growth and financial performance, but these are not necessarily synonymous—especially for small businesses. People become business owners for different reasons, so judgments about the success of their businesses may be related to any of those reasons.[47] A classic study by Churchill and Lewis identified five stages of small business growth: existence, survival, success, take-off, and resource maturity.[48] Each stage has its own challenges.

- Stage I: Existence.[49]This is the beginning. The business is up and running. The primary problems will be obtaining customers and establishing a customer base, producing products or services, and tracking and conserving cash flow.[50] The organization is simple, with the owner doing everything, including directly supervising a small number of subordinates. Systems and formal planning do not exist. The company strategy? Staying alive. The companies that stay in business move to Stage II.

- Stage II: Survival.[51] The business is now a viable operation. There are enough customers, and they are being satisfied well enough for them to stay with the business. The company’s focal point shifts to the relationship between revenues and expenses. Owners will be concerned with (1) whether they can generate enough cash in the short run to break even and cover the repair/replacement of basic assets and (2) whether they can get enough cash flow to stay in business and finance growth to earn an economic return on assets and labor. The organizational structure remains simple. Little systems development is evident, cash forecasting is the focus of formal planning, and the owner still runs everything.

- Stage III: Success.[52] The business is now economically healthy, and the owners are considering whether to leverage the company for growth or consider the company as a means of support for them as they disengage from the company.[53] There are two tracks within the success stage. The first track is the success -growth substage, where the small business owner pulls all the company resources together and risks them all in financing growth. Systems are installed with forthcoming needs in mind. Operational planning focuses on budgets. Strategic planning is extensive, and the owner is deeply involved. The management style is functional, but the owner is active in all phases of the company’s business. The second track is the success-disengagement substage, where managers take over the owner’s operational duties, and the strategy focuses on maintaining the status quo. Cash is plentiful, so the company should be able to maintain itself indefinitely, barring external environmental changes. The owners benefit indefinitely from the positive cash flow or prepare for a sale or a merger. The first professional managers are hired, and basic financial, marketing, and production systems are in place.

- Stage IV: Take-off.[54] This is a critical time in a company’s life. The business is becoming increasingly complex. The owners must decide how to grow rapidly and how to finance that growth. There are two key questions: (1) Can the owner delegate responsibility to others to improve managerial effectiveness? (2) Will there be enough cash to satisfy the demands of growth? The organization is decentralized and may have some divisions in place. Both operational planning and strategic planning are being conducted and involve specific managers. If the owner rises to the challenges of growth, it can become a very successful big business. If not, it can usually be sold at a profit.

- Stage V: Resource Maturity.[55] The company has arrived. It has the staff and financial resources to engage in detailed operational and strategic planning. The management structure is decentralized, with experienced senior staff, and all necessary systems are in place. The owner and the business have separated both financially and operationally. The concerns at this stage are to (1) consolidate and control the financial gains that have been brought on by the rapid growth and (2) retain the advantage of small size (e.g., response flexibility and the entrepreneurial spirit). If the entrepreneurial spirit can be maintained, there is a strong probability of continued growth and success. If not, the company may find itself in a state of ossification. This occurs when there is a lack of innovation and risk aversion that, in turn, will contribute to stalled or halted growth. These are common traits in large corporations.

Organizational Life Cycle

Superimposed on the stages of small business growth is the organizational life cycle (OLC), a concept that specifically acknowledges that organizations go through different life cycles, just like people do.[56] “They are born (established or formed), they grow and develop, they reach maturity, they begin to decline and age, and finally, in many cases, they die.”[57] The changes that occur in organizations have a predictable pattern,[58] and this predictability will be very helpful in formulating the objectives and strategies of a small business, altering managerial processes, identifying the sources of risk, and managing organizational change.[59] Because not all small businesses are looking to grow, however, it is likely that many small companies will retain simple organizational structures.

For those small businesses that are looking to grow, the move from one OLC stage to another occurs because the fit between the organization and its environment is so inadequate that either the organization’s efficiency and/or effectiveness is seriously impaired or the organization’s very survival is threatened. Pressure will come from changes in the nature and number of requirements, opportunities, and threats.[60]

Four OLC stages can be observed: birth, youth, midlife, and maturity. [61] In the birth cycle, a small business will have a very simple organizational structure, one in which the owner does everything. There are few, if any, subordinates. As the business moves through the youth cycle and the midlife cycle, more sophisticated structures will be adopted, and authority will be decentralized to middle- and lower-level managers. At the maturity cycle, firms will demonstrate significantly more concern for internal efficiency, install more control mechanisms and processes, and become very bureaucratic. There are other features as well that characterize the movement of an organization from birth to maturity, which are summarized in the following table:

Organizational Life Cycle Features

| Feature | Birth Cycle | Youth Cycle | Midlife Cycle | Maturity Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Small | Medium | Large | Very large |

| Bureaucratic | Nonbureaucratic | Prebureaucratic | Bureaucratic | Very bureaucratic |

| Division of labor | Overlapping tasks | Some departments | Many departments | Extensive, with small jobs and many descriptions |

| Centralization | One-person rule | Two leaders rule | Two department heads | Top-management heavy |

| Formalization | No written rules | Few rules | Policy and procedure manuals | Extensive |

| Administrative intensity | Secretary, no professional staff | Increasing clerical and maintenance | Increasing professional and staff support | Large-multiple departments |

| Internal systems | Nonexistent | Crude budget and information | Control systems in place: budget, performance, reports, etc. | Extensive planning, financial, and personnel added |

| Lateral teams, task forces for coordination | None | Top leaders only | Some use of integrators and task | Frequent at lower levels to break down bureaucracy |

Source in the footnotes[62]

A small business will always be somewhere on the OLC continuum. Business success will often be based on recognizing where the business is situated along that continuum and adopting strategies best suited to that place in the cycle.

Industry Life Cycle

The industry life cycle is another dimension of small business evolution, which needs to be understood and assessed in concert with the stages of small business growth and the OLC. All small businesses compete in an industry, and that industry will experience a life cycle just as products and organizations do. Although there may be overlap in the names of the ILC stages, the meaning and implications of each stage are different.

The industry life cycle (ILC) refers to the continuum along which an industry is born, grows, matures, and eventually, experiences decline and then dies. Although the pattern is predictable, the duration of each stage in the cycle is not. The stages are the same for all industries, but every industry will experience the stages differently. The stages will last longer for some and pass quickly for others; even within the same industry various small businesses may find themselves at different life cycle stages.[63] However, no matter where a small business finds itself along the ILC continuum, the strategic planning of that business will be influenced in important ways.

According to one study, the ILC, charted on the basis of the growth of an industry’s sales over time, can be observed as having four stages: introduction, growth, maturity, and decline. The introduction stage[64] finds the industry in its infancy. Although it is possible for a small business to be alone in the industry as a result of having developed and introduced something new to the marketplace, this is not the usual situation. The business strategy will focus on stressing the uniqueness of the product or the service to a small group of customers, commonly referred to as innovators or early adopters. A significant amount of capital is required. Profits are usually negative for both the firm and the industry.

The growth stage[65] is the second ILC stage. This stage also requires a significant amount of capital, but increasing product standardization may lead to economies of scale that will, in turn, increase profitability. The strategic focus is product differentiation, with an increased focus on responding to customer needs and interests. Intense competition will result as more new competitors join the industry, but many firms will be profitable. The duration of the growth stage will be industry dependent.

The maturity stage[66]will see some competition from late entrants that will try to take market share away from existing companies. This means that the marketing effort must continue to focus on product or service differentiation. There will be fewer firms in mature industries, so those that survive will be larger and more dominant. Many small businesses may move into the ranks of midsize or big businesses.

The decline stage[67] occurs in most industries. It is typically triggered by a product or service innovation that renders the industry obsolete. Sales will suffer, and the business goes into decline. Some companies will leave the industry, but others will remain to compete in the smaller market. The smaller businesses may be more agile for competing in a declining industry, but they will need to carefully formulate their business strategies to remain viable.

Key Takeaways

- Small-business management should consider the growth stages, the OLC, and the ILC in its planning.

- There are five stages of small business growth: existence, survival, success, take-off, and resource maturity. The success stage includes two substages, growth and disengagement. Ossification may result if a mature small business loses its entrepreneurial spirit and becomes more risk-averse.

- Some small businesses may not be looking to grow, so they may remain in the survival stage.

- The OLC refers to the four stages of development that organizations go through: birth, youth, midlife, and maturity.

- Some small businesses may stick with the very simple organizational structures because they are not interested in growing to the point where more complicated structures are required.

- The ILC is the time continuum along which an industry is born, grows, matures, declines, and dies.

- There are four stages in the ILC: introduction, growth, maturity, and decline.

The Big Two: Customer Value and Cash Flow

#1 Creating Customer Value

In 1916, Nathan Hanwerker was an employee at one of the largest restaurants on Coney Island—but he had a vision. Using his wife’s recipe, he and his wife opened a hot dog stand. He believed that the combination of a better-tasting hot dog and the nickel price, half that of his competitors, was his recipe for success. He was wrong. Unfortunately for Nathan, Upton Sinclair’s book The Jungle a decade before had made the public suspicious of low-cost meat products. Nathan discovered that his initial business model was not working. Customers valued taste and cost, but they also valued the quality of a safe product. To convince customers that his hot dogs were safe, he secured several doctors’ smocks and had people wear them. The sight of “doctors” consuming Nathan’s hot dogs gave customers the extra value that they needed. It was all about the perception of quality. If doctors were eating the hot dogs, they must be OK. Today there are over 20,000 outlets serving Nathan’s hot dogs.[68]

In principle, customer value is a very simple concept. It is the difference between the benefits that a customer receives from a product or a service and the costs associated with obtaining that product or service. Total customer benefit refers to the perceived monetary value of the bundle of economic, functional, and psychological benefits customers expect from a product or a service because of the products, services, personnel, and images involved. Total customer cost, the perceived bundle of costs that customers expect to occur when they evaluate, obtain, use, and dispose of the product or use the service, include monetary, time, energy, and psychological costs.[69] In short, it is all about what customers get and what they have to give up.

In reality, the creation of customer value will always be a challenge—particularly because it almost always needs to be defined on the customer’s terms.[70] Nonetheless, “the number one goal of business should be to ‘maximize customer value and strive to increase value continuously.’ If a firm maximizes customer value, relative to competitors, success will follow. If a firm’s products are viewed as conveying little customer value, the firm will eventually atrophy and fail.” [71] This will certainly be true for the small business that is much closer to its customers than the large business.

The small business owner needs to be thinking about customer value every day: what is offered now, how it can be made better, and what the competition is doing that is offering more value. It is not easy, but it is essential. All business decisions will add to or detract from the value that can be offered to the customer. If your product or service is perceived to offer more value than that of the competition, you will get the sale. Otherwise, you will not get the sale.

#2 Cash Flow

Most people would define success with respect to profits or sales. This misses a critical point. The survival of a firm hinges not so much on sales or profits, although these are vitally important, as it does on the firm’s ability to meet its financial obligations. A firm must learn to properly manage its cash flow, defined as the money coming into and flowing from a business because cash is more than king. It is a firm’s lifeblood. As the North Dakota Small Business Development Center put it, “Failure to properly plan cash flow is one of the leading causes for small business failure.” [72]

An understanding of cash flow requires some understanding of accounting systems. There are two types: cash-based and accrual. In a cash-based accounting system, sales are recorded when you receive the money. This type of system is really meant for small firms with sales totaling less than $1 million. Accrual accounting systems, by contrast, are systems that focus on measuring profits. They assume that when you make a sale, you are paid at that point. However, almost all firms make sales on credit, and they also make purchases on credit. Add in that sales are seldom constant, and you begin to see how easily and often cash inflows and outflows can fall out of sync. This can reduce a firm’s liquidity, which is its ability to pay its bills. Envision the following scenario: A firm generates tremendous sales by using easy credit terms: 10 percent down and one year to pay the remaining 90 percent. However, the firm purchases its materials under tight credit terms. In an accrual accounting system, this might appear to produce significant profits. However, the firm may be unable to pay its bills and salaries. In this type of situation, the firm, particularly the small firm, can easily fail.

There are other reasons why cash flow is critically important. Firms need to have the money to buy new materials or expand. In addition, firms should have cash available to meet unexpected contingencies or investment opportunities.

Cash flow management requires a future-focused orientation. You have to anticipate your future cash inflows and outflows and what actions you may need to take to preserve your liquidity. Today, even the nonemployee firm can begin this process with simple spreadsheet software. Slightly larger firms could opt for the user-dedicated software. In either case, cash-flow analysis requires the owner to focus on the future and to develop effective planning skills.

Cash-flow management also involves activities such as expense control, receivables management, inventory control, and developing a close relationship with commercial lenders. The small business owner needs to think about these things every day. Their requirements may tax many small business operators, but they are essential skills.

- Expense control requires owners or operators to think in terms of constantly seeking out efficiencies and cost-reduction strategies.

- Receivables management forces owners to think about how to walk the delicate balance of offering customers the benefits of credit while trying to receive the payments as quickly as possible. They can use technology and e-business to expedite the cash inflow.

- Effective Inventory control translates into an understanding of the ABC classification system (sorting inventory by volume and value), and determining order quantities and reorder points. Inevitably, any serious consideration of inventory management leads one to the study of “lean” philosophies. Lean inventory management refers to approaches that focus on minimizing inventory by eliminating all sources of waste. Lean inventory management inevitably leads its practitioners to adopt a new process-driven view of the firm and its operations.

- Lastly, attention to cash-flow management recognizes that there may well be periods when cash outflows will exceed cash inflows. You may have to use commercial loans, equity loans (pledging physical assets for cash), and/or lines of credit. These may not be offered by a lender at the drop of a hat. Small-business owners need to anticipate these cash shortfalls and should already have an established working relationship with a commercial lender.

A small business needs to be profitable over the long term if it is going to survive. However, this becomes problematic if the business is not generating enough cash to pay its way on a daily basis.[73] Cash flow can be a sign of the health—or pending death—of a small business. The need to ensure that cash is properly managed must therefore be a top priority for the business.[74] This is why cash-flow implications must be considered when making all business decisions. Everything will be a cash flow factor one way or the other. Fred Adler, a venture capitalist, could not have said it better when he said, “Happiness is a positive cash flow.”[75]

Key Takeaways

- The creation of customer value must be a top priority for small business. The small business owner should be thinking about it every day.

- Cash flow is a firm’s lifeblood. Without a positive cash flow, a small business cannot survive. All business decisions will have an impact on cash flow—which is why small business owners must think about it every day.

- A cash-based accounting system is for small firms with sales totaling less than $1 million. Accrual accounting systems measure profits instead of cash.

Please email any errors in this – or subsequent – chapters to Jason Anderson at jason.anderson@ku.edu.

- "Small Business by the Numbers,” National Small Business Administration, accessed October 7, 2011, www.nsba.biz/docs/bythenumbers.pdf. ↵

- Mansel Blackford, The History of Small Business in America, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 4. ↵

- Katherine Kobe, “The Small Business Share of GDP, 1998–2004,” Small Business Research Summary, April 2007, accessed October 7, 2011, http://archive.sba.gov/advo/research/rs299tot.pdf. ↵

- Zoltan J. Acs and David B. Audretsch. “Innovation in Large and Small Firms: An Empirical Analysis,” American Economic Review 78, no. 4 (1988): 678–90. ↵

- “Small Business by the Numbers,” National Small Business Administration, accessed October 7, 2011, www.nsba.biz/docs/bythenumbers.pdf. ↵

- Jeff Cornwall, “Innovation in Small Business,” The Entrepreneurial Mind, March 16, 2009, accessed June 1, 2012, http://www.drjeffcornwall.com/2009/03/16/innovation _in_small_business/. ↵

- “Small Business by the Numbers,” National Small Business Administration, accessed October 7, 2011, www.nsba.biz/docs/bythenumbers.pdf. ↵

- US Census Bureau, “Statistics of U.S. Business,” accessed October 7, 2011, http://www.census.gov/econ/susb. ↵

- “Statistics of U.S. Businesses,” US Census Bureau, April 13, 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.census.gov/econ/susb. ↵

- William J Dennis Jr., Bruce D. Phillips, and Edward Starr, “Small Business Job Creation: The Findings and Their Critics”, Business Economics 29, no. 3 (1994): 23–30. ↵

- “Statistics of U.S. Businesses,” US Census Bureau, April 13, 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.census.gov/econ/susb. ↵

- K. J. Stanworth and J. Curran, “Growth and the Small Firm: An Alternative View,” Journal of Management Studies 13, no. 2 (1976): 95–111. ↵

- William Dunkelberg and A. C. Cooper. “Entrepreneurial Typologies: An Empirical Study,” Frontiers of Entrepreneurial Research, ed. K. H. Vesper (Wellesley, MA: Babson College, Centre for Entrepreneurial Studies, 1982), 1–15. ↵

- “Report on the Commission or Enquiry on Small Firms,” Bolton Report, vol. 339 (London: HMSO, February 1973), 156–73. Paul Burns and Christopher Dewhurst, Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 2nd ed. (Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan, 1996), 17. Graham Beaver, Business, Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Development (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002), 33. ↵

- Terry L. Besser, “Community Involvement and the Perception of Success Among Small Business Operators in Small Towns,” Journal of Small Business Management 37, no 4 (1999): 16. ↵

- Roger Dickinson, “Business Failure Rate,” American Journal of Small Business 6, no. 2 (1981): 17–25. ↵

- A. B. Cochran, “Small Business Failure Rates: A Review of the Literature,” Journal of Small Business Management 19, no. 4, (1981): 50–59. ↵

- Don Bradley and Chris Cowdery, “Small Business: Causes of Bankruptcy,” July 26, 2004, accessed October 7, 2011, www.sbaer.uca.edu/research/asbe/2004_fall/16.pdf. ↵

- “Equifax Study Shows the Ups and Downs of Commercial Credit Trends,” Equifax, 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.equifax.com/PR/pdfs/CommercialFactSheetFN3810.pdf. ↵

- Don Bradley and Chris Cowdery, “Small Business: Causes of Bankruptcy,” July 26, 2004, accessed October 7, 2011, www.sbaer.uca.edu/research/asbe/2004_fall/16.pdf. ↵

- Don Bradley and Chris Cowdery, “Small Business: Causes of Bankruptcy,” July 26, 2004, accessed October 7, 2011, www.sbaer.uca.edu/research/asbe/2004_fall/16.pdf. ↵

- Anita Campbell, “Business Failure Rates Is Highest in First Two Years,” Small Business Trends, July 7, 2005, accessed October 7, 2011, smallbiztrends.com/2005/07/business-failure-rates-highest-in.html. ↵

- T. C. Carbone, “The Challenges of Small Business Management,” Management World 9, no. 10 (1980): 36. ↵

- John Argenti, Corporate Collapse: The Causes and Symptoms (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976), 45. ↵

- Graham Beaver, “Small Business: Success and Failure,” Strategic Change 12, no. 3 (2003): 115–22. ↵

- Sharon Nelton, “Ten Key Threats to Success,” Nation’s Business 80, no. 6 (1992): 18–24. ↵

- Robert N. Steck, “Why New Businesses Fail,” Dun and Bradstreet Reports 33, no. 6 (1985): 34–38. ↵

- G. E. Tibbits, “Small Business Management: A Normative Approach,” in Small Business Perspectives, ed. Peter Gorb, Phillip Dowell, and Peter Wilson (London: Armstrong Publishing, 1981), 105.,Jim Brown, Business Growth Action Kit (London: Kogan Page, 1995), 26. ↵

- Christopher Orpen, “Strategic Planning, Scanning Activities and the Financial Performance of Small Firms,” Journal of Strategic Change 3, no. 1 (1994): 45–55. ↵

- Sandra Hogarth-Scott, Kathryn Watson, and Nicholas Wilson, “Do Small Business Have to Practice Marketing to Survive and Grow?,” Marketing Intelligence and Planning 14, no. 1 (1995): 6–18. ↵

- Isaiah A. Litvak and Christopher J. Maule, “Entrepreneurial Success or Failure—Ten Years Later,” Business Quarterly 45, no. 4 (1980): 65.,Hans J. Pleitner, “Strategic Behavior in Small and Medium-Sized Firms: Preliminary Considerations,” Journal of Small Business Management 27, no. 4 (1989): 70–75. ↵

- Richard Monk, “Why Small Businesses Fail,” CMA Management 74, no. 6 (2000): 12. Anonymous, “Top-10 Deadly Mistakes for Small Business,” Green Industry Pro 19, no. 7 (2007): 58. ↵

- Rubik Atamian and Neal R. VanZante, “Continuing Education: A Vital Ingredient of the ‘Success Plan’ for Business,” Journal of Business and Economic Research 8, no. 3 (2010): 37–42. ↵

- T. Carbone, “Four Common Management Failures—And How to Avoid Them,” Management World 10, no. 8 (1981): 38–39. ↵

- Anonymous, “Top-10 Deadly Mistakes for Small Business,” Green Industry Pro 19, no. 7 (2007): 58. ↵

- Rubik Atamian and Neal R. VanZante, “Continuing Education: A Vital Ingredient of the ‘Success Plan’ for Business,” Journal of Business and Economic Research 8, no. 3 (2010): 37–42. ↵

- Howard Upton, “Management Mistakes in a New Business,” National Petroleum News 84, no. 10 (1992): 50. ↵

- Rubik Atamian and Neal R. VanZante, “Continuing Education: A Vital Ingredient of the ‘Success Plan’ for Business,” Journal of Business and Economic Research 8, no. 3 (2010): 37–42., Arthur R. DeThomas and William B. Fredenberger, “Accounting Needs of Very Small Business,” The CPA Journal 55, no. 10 (1985): 14–20. ↵

- Roger Brown, “Keeping Control of Your Credit,” Motor Transportation, April 2009, 8. ↵

- Arthur R. DeThomas and William B. Fredenberger, “Accounting Needs of Very Small Business,” The CPA Journal 55, no. 10 (1985): 14–20. ↵

- Hugh M. O’Neill and Jacob Duker, “Survival and Failure in Small Business,” Journal of Small Business Management 24, no. 1 (1986): 30–37. ↵

- Arthur R. DeThomas and William B. Fredenberger, “Accounting Needs of Very Small Business,” The CPA Journal 55, no. 10 (1985): 14–20. ↵

- Jim Everett and John Watson, “Small Business Failures and External Risk Factors,” Small Business Economics 11, no. 4 (1998): 371–90. ↵

- Jim Everett and John Watson, “Small Business Failures and External Risk Factors,” Small Business Economics 11, no. 4 (1998): 371–90. ↵

- Roger Ehrenberg, “Monitor 110: A Post Mortem—Turning Failure into Learning,” Making It!, August 27, 2009, accessed June 1, 2012, http://www.makingittv.com/Small-Business-Entrepreneur-Story-Failure.htm. ↵

- “Organizational Life Cycle,” Inc., 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.inc.com/encyclopedia/organizational-life-cycle.html. ↵

- B. Kotey and G. G. Meredith, “Relationships among Owner/Manager Personal Values, Business Strategies, and Enterprise Performance,” Journal of Small Business Management 35, no. 2 (1997): 37–65. ↵

- Neil C. Churchill and Virginia L. Lewis, “The Five Stages of Small Business Growth,” Harvard Business Review 61, no. 3 (1983): 30–44, 48–50. ↵

- Neil C. Churchill and Virginia L. Lewis, “The Five Stages of Small Business Growth,” Harvard Business Review 61, no. 3 (1983): 30–44, 48–50. ↵

- Darrell Zahorsky, “Find Your Business Life Cycle,” accessed October 7, 2011, sbinformation.about.com/cs/marketing/a/a040603.htm. ↵

- Neil C. Churchill and Virginia L. Lewis, “The Five Stages of Small Business Growth,” Harvard Business Review 61, no. 3 (1983): 30–44, 48–50. ↵

- Neil C. Churchill and Virginia L. Lewis, “The Five Stages of Small Business Growth,” Harvard Business Review 61, no. 3 (1983): 30–44, 48–50. ↵

- Shivonne Byrne, “Empowering Small Business,” Innuity, June 25, 2007, accessed October 7, 2011, innuity.typepad.com/innuity_empowers_small_bu/2007/06/five -stages-of-.html. ↵

- Neil C. Churchill and Virginia L. Lewis, “The Five Stages of Small Business Growth,” Harvard Business Review 61, no. 3 (1983): 30–44, 48–50. ↵

- Neil C. Churchill and Virginia L. Lewis, “The Five Stages of Small Business Growth,” Harvard Business Review 61, no. 3 (1983): 30–44, 48–50. ↵

- Carter McNamara, “Basic Overview of Organizational Life Cycles,” accessed October 7, 2011, http://managementhelp.org/organizations/life-cycles.htm. ↵

- “Organizational Life Cycle,” Inc., 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.inc.com/encyclopedia/organizational-life-cycle.html. ↵

- Robert E. Quinn and Kim Cameron, “Organizational Life Cycles and Shifting Criteria of Effectiveness: Some Preliminary Evidence,” Management Science 29, no. 1 (1983): 33–51. ↵

- “Organizational Life Cycle,” Inc., 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.inc.com/encyclopedia/organizational-life-cycle.html.,Yash P. Gupta and David C. W. Chin, “Organizational Life Cycle: A Review and Proposed Directions for Research,” The Mid-Atlantic Journal of Business 30, no. 3 (December 1994): 269–94. ↵

- “Organizational Life Cycle,” Inc., 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.inc.com/encyclopedia/organizational-life-cycle.html. ↵

- Carter McNamara, “Basic Overview of Organizational Life Cycles,” accessed October 7, 2011, http://managementhelp.org/organizations/life-cycles.htm. ↵

- Richard L. Daft, Organizational Theory and Design (St. Paul, MN: West Publishing, 1992), as cited in Carter McNamara, “Basic Overview of Organizational Life Cycles,” accessed October 7, 2011, http://managementhelp.org/organizations/life-cycles.htm. ↵

- “Industry Life Cycle,” Inc., 2010, accessed June 1, 2012, www.inc.com/encyclopedia/industry-life-cycle.html. ↵

- “Organizational Life Cycle,” Inc., 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.inc.com/encyclopedia/organizational-life-cycle.html. ↵

- “Organizational Life Cycle,” Inc., 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.inc.com/encyclopedia/organizational-life-cycle.html. ↵

- “Organizational Life Cycle,” Inc., 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.inc.com/encyclopedia/organizational-life-cycle.html. ↵

- "Organizational Life Cycle,” Inc., 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, www.inc.com/encyclopedia/organizational-life-cycle.html. ↵

- John A. Jakle and Keith A. Sculle, Fast Food (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 163–64. ↵

- Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane, Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice-Hall, 2009), 121. ↵

- H. Whitelock, “How to Create Customer Value,” eZine Articles, March 16, 2007, accessed October 7, 2011, ezinearticles.com/?How-to-Create-Customer-Value &id=491697. ↵

- Earl Nauman, Creating Customer Value: The Path to Sustainable Competitive Advantage (New York: Free Press, 1995), 16. ↵

- “Why Is Cash Flow So Important?,” North Dakota Small Business Development Center, 2005, accessed October 7, 2011, www.ndsbdc.org/faq/default.asp?ID=323. ↵

- Barry Minnery, “Don’t Question the Importance of Cash Flow: Making a Profit Is the Goal but Day-to-Day Costs Must Be Met in Order to Keep a Business Afloat,” The Independent.com, May 28, 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, http://www.articlesezinedaily.com/dont-question-the-importance-of-cash-flow/. ↵

- Barry Minnery, “Don’t Question the Importance of Cash Flow: Making a Profit Is the Goal but Day-to-Day Costs Must Be Met in Order to Keep a Business Afloat,” The Independent.com, May 28, 2010, accessed October 7, 2011, http://www.articlesezinedaily.com/dont-question-the-importance-of-cash-flow/. ↵

- Fred Adler, QuotationsBook.com, accessed October 7, 2011, quotationsbook.com/quote/18235. ↵

The government agency that is charged with aiding, counseling, assisting, and protecting the interests of small business.

A firm that is independently owned and operated and not dominant in its field of operation. There are variations across industries with respect to competitiveness, entry and exit costs, distribution by size, growth rates, and technological change.

The failure of a firm is based on the limitations of its owner, such as a lack of business skills or a lack of behavior skills.

The failure of a firm is based on financial issues, such as having inadequate financing at the beginning, inadequate financial controls, poor cash-flow management, and the inability to raise additional capital.

The failure of the firm is based on external factors, such as a downturn in the economy, rising interest rates, or changes in customer demand.

The five stages that small businesses may go through: existence, survival, success, take-off, and resource maturity.

A business is up and running, and the strategy is to stay alive.

A business is viable, and the focus shifts to revenues and expenses.

A business is economically healthy. The owners are considering leveraging the company for growth or using the company as a means of support while disengaging.

An owner risks all resources in financing growth.

An owner’s operational duties are assumed by managers. The focus is on maintaining the status quo.

A business becomes increasingly complex. The owner must decide how to grow rapidly and finance growth.

A business has demonstrated success. There is a strong chance of continued growth and success if entrepreneurial spirit can be maintained.

The four stages that organizations go through in their development: birth, youth, midlife, and maturity.

A business is small and has a simple organizational structure; the owner does everything.

A business is medium-sized. It has some departments, a few rules, and is prebureaucratic.

A business has many departments, is bureaucratic, and has policy and procedure manuals.

A business demonstrates significantly more concern for internal efficiency, install more control mechanisms and processes, and become very bureaucratic

The life stages that characterize an industry.

An industry is in infancy; significant cash is required, and profits are usually negative.

An industry in which significant capital is required, economies of scale kick in, and many firms are profitable.

A business is very large, very bureaucratic, and top-management heavy. An industry in which there is competition from late entrants and where the marketing focus is on differentiation.

An industry that is triggered by product or service innovation. The industry becomes obsolete, sales suffer, and many companies leave.

The difference between the benefits a customer receives from a product or a service and the costs associated with obtaining the product or the service.

The perceived monetary value of economic, functional, and psychological benefits customers expect from a product or a service because of the products, services, personnel, and images involved.

The perceived bundle of costs customers expect to incur when they evaluate, obtain, use, and dispose of the product or the service.

The money coming into and exiting a business.

Sales are recorded when the money is received.

The focus is on measuring profits and matching revenues to expenses.

The ability of a small business to pay its bills.

Expense control, receivables management, inventory control, and developing a close relationship with commercial lenders.

Seeking out efficiencies and cost-reduction strategies.

Trying to receive customer payments as quickly as possible.

Ensuring that goods are where customers want them when they want them.

A method of inventory management by which items are ranked according to their volume and value.

Minimizing inventory by eliminating sources of waste.

Pledging physical assets for cash.