10 Chapter 10 – Financial Management

The Importance of Financial Management in Small Business

Chapter 9 “Accounting and Cash Flow” discusses the critical importance of a small business owner understanding the fundamentals of accounting—“the language of business.” This chapter examines finance and argues that the small business owner should acquire a basic understanding of some key principles in this discipline. One question that might come to someone’s mind immediately is as follows: “What is the difference between accounting and finance?” As an academic discipline, finance began in the early decades of the twentieth century. We have already seen that accounting predates the formal study of finance by millennia.[1] Yet some have argued that accounting should be seen as a subset of finance.[2] Others have argued that both accounting and finance should be seen as subdisciplines of economics. Not surprisingly, others have argued in favor of the primacy of accounting. If we get beyond this debate, we can see that accounting is involved with the precise reporting of the financial position of a firm through the financial statements. The accounting function is expected to collect, organize, and present financial information in a systematic fashion. Finance can be seen as “the science of money management” and consists of three major activities: financial planning, financial control, and financial decision making. Financial planning deals with the acquisition of adequate funds to maintain the operations of a business and making sure that funds are available when needed. Control seeks to assure that assets are being efficiently used. Decision-making is associated with determining how to acquire funds, where to acquire funds, and how those funds should be used and within the context of the risk assessment of the aforementioned decisions. As an academic discipline, finance has grown tremendously over the last four decades.

Much of the work produced during this period possessed both an esoteric analytical quality and profound practical consequences. One only has to look at newspapers and the business press, during the last few years, to see how financial theory (efficient market hypothesis) and financial models (options pricing, derivatives, and arbitrage models) have played a dominant role in the global economy. Fortunately, most small businesses have no need to directly involve themselves with these analytical abstractions. But this does not mean that small business owners do not need to concern themselves with fundamental issues of financing their firms.

Acquisition of Funds

Capital is the lifeblood of all businesses. It is needed to start, operate, and expand a business. Capital comes from several sources: equity, debt, internally generated funds, and trade credits.

Sources of Capital

Equity financing raises money by selling a certain share of the ownership of the business. It involves no explicit obligation or expectation, on the part of the investors, to be repaid their investment. The value of equity financing lies in the partial ownership of the business.

Perhaps the major source of equity financing for most small start-up businesses comes from personal savings. The term bootstrapping refers to using personal, family, or friends’ money to start a business.[3] The use of one’s own money (or that of family and friends) is a strong indicator that a business owner has a strong commitment to and belief in the success of the business. If a business is financed totally from one’s personal savings, that means the owner or the operator has total control of the business.

If a business is structured as a corporation, it may issue stock. Generally, two major types of stock may be issued: common stock and preferred stock. It should be noted that in most cases, owners of common stock have what are known as voting rights. They have a proportional vote (directly related to the number of shares they own) for members of the board of directors. Preferred stock does not carry with it voting rights, but it has a form of guaranteed dividend.

Corporations that issue stock must comply with several steps to meet both federal and state statutes, including the following: outlines to issue stock to shareholders, determining the price and number of shares to be issued, creating stock certificates; developing a record to record all stock transactions; and meeting all federal and state securities requirements.[4] Smaller businesses may choose to issue stock only to those who were involved in the initial investment of the business. In such cases, one generally does not have to register these securities with state or federal agencies. However, one may be required to fill out all the forms.[5]

Chapter 5 “The Business Plan” discusses two sources of capital investment: venture capitalist and angel investors. Venture capitalists are looking for substantial returns on their initial investment—five, ten, sometimes even twenty-five times their original investment. They will be looking for firms that can rapidly generate significant profits or significant growth in sales. Angel investors may be more attracted to their interest in the small business concept than in reaping significant returns. This is not to say that they are not interested in recouping their original investment with some type of significant return. It is much more likely that angel investors, as compared to venture capitalists, will play a much more active role in the decision-making process of the small business.

One area for possible capital infusion into a small business may come from a surprising source. Many students (and some adults) may find funding to start up a business through business plan competitions. These competitions are often hosted by colleges and universities or small business associations. The capital investment may not be large, but it might be enough to start very small businesses.

Debt financing represents a legal obligation to repay the original debt plus interest. Most debt financing involves a fixed payment schedule to repay both principal and interest. A failure to meet the schedule has serious consequences, which might include the bankruptcy of the business. Those who provide debt financing expect that the principal will be repaid with interest, but they are not formal investors in the business.

There are numerous sources for debt financing. Some small businesses begin with financing by borrowing from friends and family. Some firms may choose to finance business operations by using either personal or corporate credit cards. This approach to financing can be extraordinarily expensive given the interest rates charged on credit cards and the possibility that the credit card companies may change (by a significant amount) the credit limit associated with the credit card.

The largest source of debt financing for small businesses in the United States comes from commercial banks.[6] Bank lending can take many forms. The most common loan specifies the amount of money to be repaid within a specific time frame for a specific interest rate. These loans can be either secured or unsecured. Secured loans involve pledging some assets—such as a home, real estate, machinery, and plant—as collateral. Unsecured loans provide no such collateral. Because they are riskier for the bank, they generally have higher interest rates.

The Small Business Administration (SBA) has a large number of programs designed to help small businesses. These include the business loan programs, investment programs, and bonding programs. The SBA operates three different loan programs. It should be understood that the SBA does not make the loan itself to a small business but rather guarantees a portion of the loan to its partners that include private lenders, microlending institutions, and community development organizations. To secure one of these loans, the borrower must meet criteria set forth by the SBA. It should be recognized that these SBA loan rules and guidelines can be altered by the US Congress and are dependent on prevailing economic and political conditions. The following subsections briefly describe some of the loan programs used by the SBA.

Loan Programs

This class of loans may be used for a variety of reasons, including the purchase of land, buildings, equipment, machinery, supplies, or materials. It may also be used for long-term working capital (paying accounts payable or the purchase of inventory). It may even be used to purchase an existing business. This class of loans cannot, however, be used to refinance existing debt, to pay delinquent taxes, or to change business ownership.

- Special-purpose loans program. These loans are designed to assist small businesses for specific purposes. They have been used to help small businesses purchase and incorporate pollution control systems, develop employee stock ownership plans, and aid companies negatively impacted by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). It includes programs such as the CAPLines, which provide assistance to businesses for meeting their short-term working capital needs. There is also the Community Adjustment and Investment Program. This program is designed to assist businesses that might have been adversely impacted by NAFTA.

- Express and pilot programs. These loan programs are designed to accelerate the process of providing loans. SBA Express can respond to a loan application within thirty-six hours while also providing lower interest rates.

- Community express programs. These programs are designed to assist borrowers whose businesses are located in economically depressed regions of the country.

- Patriot express loans. These loans are designed to assist members of the US military who wish to create or expand a small business. These loans have lower interest rates and can be used for starting a business, real estate purchases, working capital, expansions, and helping the business if the owner should be deployed.

-

Export loan programs. Given the remarkable fact that 70 percent of American exporters have less than twenty employees, it is not surprising that the SBA makes a special effort to support these businesses by providing specialized loan programs. These programs include the following:

- Export Express Program. This program has a rapid turnaround time to support export-based activities. It can provide for funds up to $500,000 worth of financing. Financing can be either a term loan or a line of credit.

- Export Working Capital Program. A major challenge that small exporters face is the fact that many American banks will not provide working capital advances on orders, receivables, or even letters of credit. This SBA program assures up to the 90 percent of a loan so as to enhance a business’s export working capital.

- SBA and Ex-Im Bank Coguarantee Program. This is an extension of the Export Working Capital Program and deals with expanding a business’s export working capital lines up to $2 million.

- International Trade Loan Program. This program, with a maximum guarantee of $1.75 million, enables small businesses to start an exporting program, enlarge an exporting program, or deal with the consequences of competition from overseas imports.

Another source of debt financing is the issuance of bonds. Bonds are promissory notes. There are many forms of bonds, and here we discuss only the most basic type. The fundamental format of the bond is that it is a debt instrument that promises to repay a fixed amount of money within a given time frame while providing interest payments on a regular basis. The issuance of bonds is generally an option available to businesses with a corporation format. It also requires extensive legal and financial preparations.

Another source of capital is the generation of internal funding. This simply means that a business plows its retained earnings back into the business. This is a viable source of capital when a business is highly profitable.

The last source of capital is trade credit. Trade credit involves purchasing supplies or equipment through financing made available by vendors. This approach may allow someone to acquire inventory of materials and supplies without having the full price at the time of purchase. Some analysts say that trade credit is the second largest source of financing for small businesses after borrowing from banks.[7] Trade credit is often a vital way of securing supplies.

Trade credit is often expressed in terms of three important numbers—a discount rate, the number of days for one to pay to qualify for the discount, and the number of days on which the bill must be paid. As an example, a trade credit offered by a supplier might be listed as 5/5/30. This translates into a 5 percent discount if the bill is paid within five days of the issuance. The third number means that the bill must be paid in full within thirty days.

Capital Structure: Debt versus Equity

A critical component of financial planning for any business is determining the extent to which a firm will be financed by debt and by equity. This decision determines the financial leverage of a business. Many factors enter into this decision, particularly for the small business. From the classic economic and finance perspective, one should evaluate the cost of both debt and equity. Debt’s cost centers largely on the interest rate associated with a specific debt. Equity’s cost includes ceding control to other equity partners, the cost of issuing stock, and dividend payments. One should also consider the fact that the interest payment on debt is deductible and therefore will lower a business’s tax bill.[8] Neither the cost of issuing stock nor dividend payments is tax deductible.

Larger businesses have many more options available to them than smaller enterprises. Although this is not always true, larger businesses can often arrange for larger loans at more favorable rates than smaller businesses.[9] Larger businesses often find it easier to raise capital through the issuance of stock (equity).

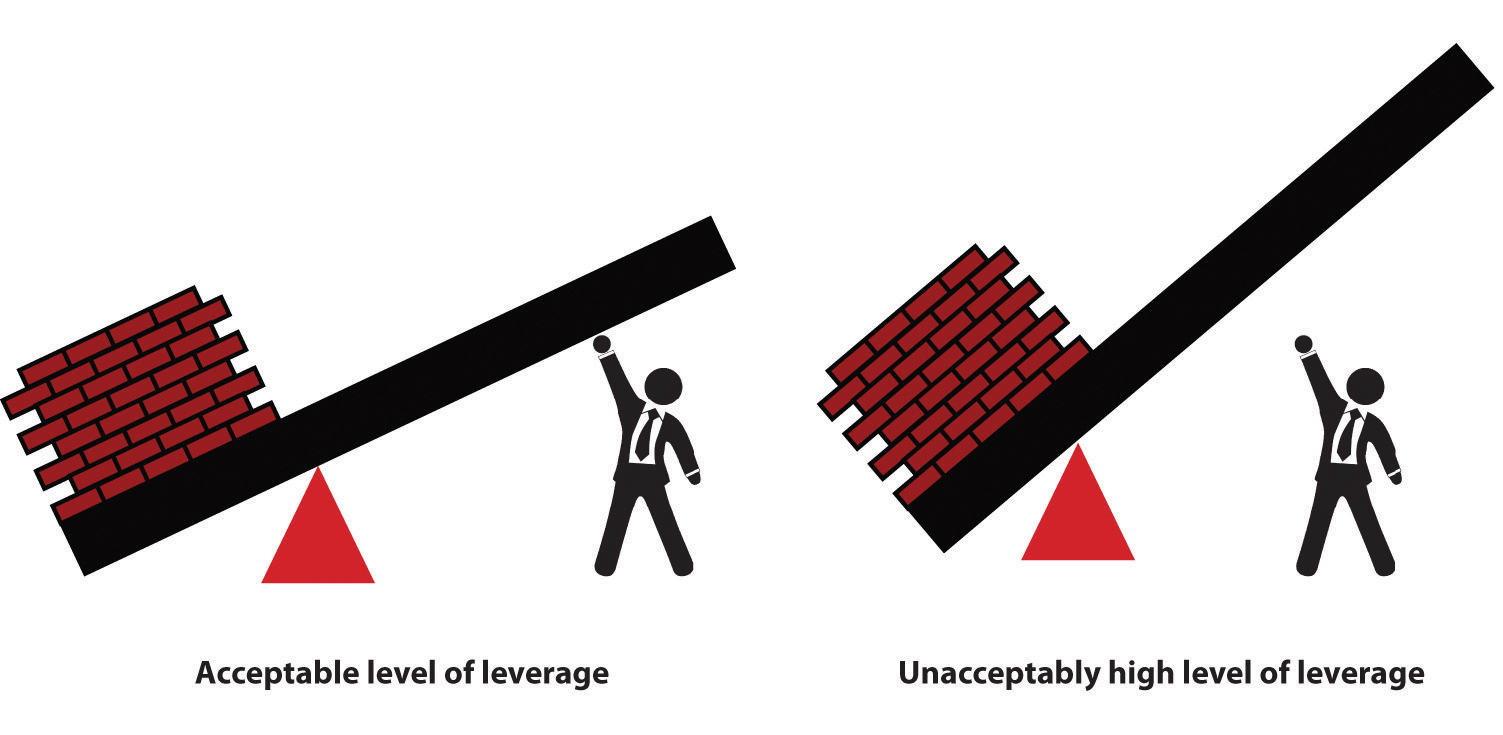

By increasing a business’s proportion of debt, its financial leverage can be increased. There are many reasons for attempting to increase a business’s financial leverage. First, one is growing the business with someone else’s money. Second, there is the deductible nature of interest on debt. Third, increasing one’s financial leverage can have a positive impact on the business’s return on equity. For all these benefits, however, there is the inescapable fact that increasing a business’s debt level also increases a business’s overall risk. The term financial leverage can be seen as being comparable to the base word—lever. Levers are tools that can amplify an individual’s power. A certain level of debt can amplify the “lifting” power of a business. However, beyond a certain point, the debt may be out of reach, and therefore the entire lifting power of financial leverage may be lost. Beyond the loss of lifting power, the assumption of too much debt may lead to an inability to pay the interest on the debt. This situation becomes the classic case of filing for bankruptcy.

Acceptable and Unacceptable Levels of Leverage

This major issue for small businesses—determining how to raise funds through either debt or equity—often transcends economic or financial decisions. For many small business owners, the ideal way of financing business growth is through generating internal funds. This means that a business does not have to acquire debt but has generated sufficient profits from its operations. Unfortunately, many small businesses, particularly at the beginning, cannot generate sufficient internal funds to finance areas such as product development, the acquisition of new machinery, or market expansions. These businesses have to rely on securing additional capital debt, equity, or some combination of both.

Many individuals start small businesses with the express purpose of finding independence and control over their own economic and business lives. This desire for independence may make many small business owners averse to the idea of equity financing because that might mean ceding business control to equity partners.[10] Another issue that makes some small business owners averse to acquiring additional equity partners is the simple fact that the acquisition of these partners means less profit to the business owner. This factor in the control issue must be considered when the small business owner is looking to raise additional capital through venture capitalist and angel investors.[11]

A recent research paper[12] examined the relationship between profitability and sources of financing for firms that had fewer than twenty-five employees. It found several rather interesting results:

- Firms that use only equity have a low probability of being profitable compared to firms that use only business or personal debt.

- Firms owned by females and minority members relied less on personal debt than male and minority owners.

- Female owners will be more likely to rely on equity from friends and family than their male counterparts.

- Firms that rely exclusively on personal savings to finance business operations will more likely be profitable than firms using equity forms of debt.

Key Takeaways

- Business owner must be aware of the implications of financing their firms.

- Owners should be aware of the financial and tax implications of the various forms of business organizations.

- Business owners should be aware of the impact of financing their firms through equity, debt, internally generated funds, and trade credit.

- Small-business owners should be aware of the various loans, grants, and bond opportunities offered by the SBA. They should also be aware of the restrictions associated with these programs.

Financial Control

Relationships with Bank and Bankers

One often hears the following standard complaint of small businesses: bankers lend money only to those businesses that do not need the money. The inverse of this complaint from the bank’s standpoint might be that small businesses request money only when they are least likely to be able to repay it. The conflict between small businesses and bankers may stem from a misunderstanding of the respective roles of both groups. At face value, it might appear—particularly to small businesses—that bankers are investing in their companies.

Under normal conditions, bankers are extremely risk-averse. This means they are not investors anticipating a substantial return predicated on the risks associated with a particular business. Bankers lend money with the clear expectation that they will be repaid both principal and interest. It is in the interest of both parties to transcend these two conflicting perceptions of the role of bankers in the life of a small business. The key way is for the small business owner to try to foster improved communications with a banker. This communication promoted by the small business owner should become the basis of a solid working relationship with the bank. Most often, this means developing a personal relationship with the loan officer of the bank, which is sometimes a problematic proposition. Bank loan officers are often moved to different branches, or they may change jobs and work for different banks. It should be the responsibility of the small business owner to maintain frequent contact with whoever is representing the bank. This should involve more than just providing quarterly statements. It should include face-to-face discussions and even asking the officer to tour a business’s facilities. The point is to personalize the working relationship between the two parties. “Ideally, it’s a human relationship as well as a business relationship,” says Bill Byne, an entrepreneur and author of Habits of Wealth.[13]

Although bankers and loan officers will rely heavily on data related to the creditworthiness of a small business, they will also consider the trustworthiness and integrity of the business owner. This intangible sense that a business owner is a worthy credit risk may play a determinant role in whether a loan is approved with the extension of a credit line. This notion of integrity has to be built over time. It is predicated on projecting an image that you can be counted on to honor what you say, know the right thing to do to make the business a success, and be able to execute the correct decisions.

It is sometimes said that bankers, when reviewing a perspective loan applicant, think of the drink “CAMPARI,” which stands for the following:

- Character. As previously stated, bankers will consider the issue of personal integrity. Part of that definition of integrity will include a sense of professionalism, which can be reflected in one’s attitude and dress. Bankers will also review one’s history as a business leader, namely one’s track record of success. This notion of character may also be extended to the upper echelon of the management team of a small business.

- Ability. The bank’s prime concern is with repayment of the principal and the interest of a loan. The loan application should clearly demonstrate a business’s ability to repay the loan. All support materials should be brought to bear to prove to the banker that the loan will not be defaulted on and will be paid in a timely fashion.

- Means. This refers to a business’s ability to function in a way so that it can repay the loan. Bankers must be convinced of this crucial point. The best way to do this is by providing a comprehensive business plan with detailed numbers that indicate the business’s ability to repay the loan. The business plan should also include the business strategy and the business model that will be employed to convince the banker of the validity of the overall plan.

- Purpose. Bankers want to know for what purpose the borrowed money will be used. You should never request a loan with the argument that having more money is better for the business than having less money. You should clearly identify how the money will be used, such as purchasing a piece of capital equipment. Having done that, you should also indicate how the acquisition of the capital equipment will positively affect the bottom line of the business.

- Amount. It would be extraordinarily inadvisable to begin a request for a business loan by saying “I need some money.” It is very important that you specify the exact amount of the loan and also justify how you determined this amount of money. As an example, you might want to identify a particular piece of capital equipment that you plan to acquire. How did you determine its price? You should be able to address what additional expenditures might be required—such as training on the use of the equipment. The greater the degree of precision that is brought to this proposal, the greater the confidence the bank might have in granting the loan.

- Repayment. This refers to demonstrating an ability to repay both the interest and the principal. Again, detailed documentation, such as sales projections, profit margins, and projected cash flows, is essential if you wish to secure the loan. It is important when generating these data that you try to be as honest as possible. Extremely positive projections may be misleading. Worse still, if they are misleading and inaccurate, it may result in the business defaulting on the loan and perhaps losing the business.

- Insurance. Even the most scrupulously developed sales and profit projections might not pan out. It would be extraordinarily useful to show contingency plans to the bank that would indicate how you would repay the loan in the event that the scenarios that you have identified do not come to fruition.

One should recognize that a good relationship with the bank can yield benefits above and beyond credit lines and business loans. Bankers can serve as interlocutors, connecting you to potential customers, suppliers, and other investors. A good working relationship with a bank can be the best reference a business could have. This is particularly true in the current business climate where bankers have significantly restricted lending to small businesses.

Key Takeaways

- Any business owner must be aware that bankers consider several factors when considering a loan decision.

- Business owners should be aware of their own and their business’s creditworthiness.

- Business owners should be aware that bankers appreciate precision, particularly when it comes to the exact size of the loan, its purpose, and how it will be repaid.

Financial Decision-Making

Breakeven Analysis

A breakeven analysis is remarkably useful to someone considering starting up a business. It examines a business’s potential costs—both fixed and variable—and then determines the sales volume necessary to produce a profit for given selling price.[14] This information enables one to determine if the entire concept is feasible. After all, if one has to sell five million shoes in a small town to turn a profit, one would immediately recognize that there may be a severe problem with the proposed business model.

A breakeven analysis begins with several simplifying assumptions. In its most basic form, it assumes that you are selling only one product at a particular price, and the production cost per unit is constant over a wide range of values. The purpose of a breakeven analysis is to determine the sales volume that is required so that you neither lose money nor make a profit. This translates into a situation in which the profit level is zero. Put in equation form, this simply means

total revenue − total costs = $0

By moving terms, we can see that the break-even point occurs when total revenues equal total costs:

total revenue = total costs

We can define total revenue as the selling price of the product times the number of units sold, which can be represented as follows:

total revenue (TR) = selling price (SP) × sales volume (Q)

TR = SP × Q

Total costs are seen as being composed of two parts: fixed costs and total variable costs. Fixed costs exist whether or not a firm produces any product or has any sales and consist of rent, insurance, property taxes, administrative salaries, and depreciation. Total variable costs are those costs that change across the volume of production. As part of the simplifying assumptions of the breakeven analysis, it is assumed that there is a constant unit cost of production. This would be based on the labor input and the amount of materials required to make one unit of product. As production increases, the total variable cost will likewise increase, which can be represented as follows:

total variable costs (TVC) = variable cost per unit (VC) × sales quantity (Q)

TVC = VC × Q

Total costs are simply the summation of fixed costs plus the total variable costs:

total costs (TC) = [fixed costs (FC) + total variable cost (TVC)]

TC = FC + TVC

The original equation for the break-even point can now be rewritten as follows:

[selling price (SP) × sales volume (Q)] − total costs (TC) = $0

(SP × Q) − TC = $0

At the break-even point, revenues equal total costs, so this equation can be rewritten as

SP × Q = TC

Given that the total costs equal the fixed costs plus the total variable costs, this equation can now be extended as follows:

selling price (SP) × sales volume (Q) = [fixed costs (FC) + total variable costs (TVC)]

SP × Q = FC + TVC

This equation can be expanded by incorporating the definition of total variable costs as a function of sales volume:

SP × Q = FC + (VC × Q)

This equation can now be rewritten to solve for the sales value:

(SP × Q) − (VC × Q) = FC

Because the term sales volume is present in both terms on the left-hand side of the equation, it can be factored to produce

Q × (SP − VC) = FC

The sales value to produce the break-even point can now be solved for in the following equation:

Q = FC / (SP − VC)

The utility of the concept of break-even point can be illustrated with the following example.

Carl Jacobs, a retired engineer, was a lifelong enthusiast of making plastic aircraft models. Over thirty years, he entered many regional and national competitions and received many awards for the quality of his model building. Part of this success was due to his ability to cast precision resin parts to enhance the look of his aircraft models. During the last ten years, he acquired a reputation as being an expert in this field of creating these resin parts. A friend of his, who started several businesses, suggested that Carl look at turning this hobby into a small business opportunity in his retirement. This opportunity stemmed from the fact that Carl had created a mold into which he could cast the resin part for a particular aircraft model; this same mold could be used to produce several hundred or several thousand copies of the part, all at relatively low cost.

Carl had experience only with sculpturing and casting parts in extremely low volumes—one to five parts at a time. If he were to create a business format for this hobby, he would have to have a significant investment in equipment. There would be a need to create multiple metal molds of the same part so that they could be cast in volume. In addition, there would be a need for equipment for mixing and melting the chemicals that are required to produce the resin. After researching, he could buy top-of-the-line equipment for a total of $33,000. He also found secondhand but somewhat less efficient equipment. Carl estimated that the total cost of acquiring all the necessary secondhand equipment would be close to $15,000. After reviewing the equipment specifications, he concluded that with new equipment, the unit cost of producing a set of resin parts for a model would run $9.25, whereas the unit cost for using the secondhand equipment would be $11.00. After doing some market research, Carl determined that the maximum price he could set for his resin sets would be $23.00. This would be true whether the resin sets were produced with new or secondhand equipment.

Carl wanted to determine how many resin sets would have to be sold to break even with each set of equipment. For simplicity’s sake, he assumed that the initial purchase price of both options would be his fixed cost.

Break-even point Analysis

| Option | Fixed Costs | Variable Cost | Selling Price | break-even point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New equipment | $33,000 | $9.25/unit | $23.00 |

Q = $33,000 / ($23.00 − $9.25) Q = $33,000 / $13.75 Q = 2,400 units |

| Secondhand equipment | $15.000 | $11.00/unit | $23.00 |

Q = $15,000 / ($23.00 − $11.00) Q = $15,000 / $12.00 Q = 1,250 units |

From this analysis, he could see that although the secondhand equipment is not as efficient (hence the higher variable cost per unit), it will break even at a significantly lower level of sales than the new equipment. Carl was still curious about the profitability of the two sets of equipment at different levels of sales. So he ran the numbers to calculate the profitability for both sets of equipment at sales levels of 1,000 units, 3,000 units, 5,000 units, 7,500 units, and 10,000 units.

Sales Level versus Profit Breakdown

| Secondhand Equipment | New Equipment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales Level | Revenue | Fixed Cost | Total Variable Costs | Profit | Revenue | Fixed Cost | Total Variable Costs | Profit |

| 1,000 | $23,000 | $15,000 | $11,000 | $(3,000) | $23,000 | $33,000 | $9,250 | $(19,250) |

| 3,000 | $69,000 | $15,000 | $33,000 | $21,000 | $69,000 | $33,000 | $27,750 | $8,250 |

| 5,000 | $115,000 | $15,000 | $55,000 | $45,000 | $115,000 | $33,000 | $46,250 | $35,750 |

| 7,500 | $172,500 | $15,000 | $82,500 | $75,000 | $172,500 | $33,000 | $69,375 | $70,125 |

| 10,000 | $230,000 | $15,000 | $110,000 | $105,000 | $230,000 | $33,000 | $92,500 | $104,500 |

From these results, it is clear that the secondhand equipment is preferable to the new equipment. At 10,000 units, the highest annual sales that Carl anticipated, the overall profits would be greater with secondhand equipment.

Capital Structure Issues in Practice

The need to balance debt and equity, with respect to financing a firm’s operations, is briefly discussed in a previous section. A critical financial decision for any business owner is determining the extent of financial leverage a firm should acquire. Building a firm using debt amplifies a return of equity to the owners; however, the acquisition of too much debt, which cannot be repaid, may lead to a bankruptcy, which represents a complete failure of the firm.

In the early 1950s, the field of finance tried to describe the effect of financial leverage on the valuation of a firm and its cost of capital.[15] A major breakthrough occurred with the works of Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller.[16] Reduced to simplest form, their works hypothesized that the valuation of a firm increases as the financial leverage increases. This is true but only up to a point. When a firm exceeds a particular value of financial leverage—namely, it has assumed too much debt—the overall value of the firm begins to decline. The point at which the valuation of a firm is maximized determines the optimal capital structure of the business. The model defined valuation as a firm’s earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) divided by its cost of capital. Cost of capital is a weighted average of a firm’s debt and equity, where equity directly relates to a firm’s stock. The reality is that this model is far more closely attuned, from a mathematical standpoint, to the corporate entity. It cannot be directly applied to most small businesses. However, the basic notion that there is some desired level of debt to equity, a level that yields maximum economic benefit, is germane, as we will now illustrate.

Let us envision a small family-based manufacturing firm that until now has been able to grow through the generation of internal funds and the equity that has been invested by the original owners. Presently, the firm has no long-term debt. It has a revolving line of credit, but in the last few years, it has not had to tap into this line of credit to any great extent. The income statement for the year 2010 and the projected income statement for 2011 are given below. In preparing the projected income statement for 2011, the firm assumed that sales would grow by 7.5 percent due to a rapidly rising market. In fact, the sales force indicated that sales could grow at a much higher rate if the firm can significantly increase its productive capacity. The projected income statement estimates the cost of goods sold to be 65 percent of the firm’s revenue. This estimate is predicated on the past five years’ worth of data.

Income Statement for 2010 and Projections for 2011

| 2010 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|

| Revenue | $475,000 | $510,625 |

| Cost of goods sold | $308,750 | $331,906 |

| Gross profit | $166,250 | $178,719 |

| General sales and administrative | $95,000 | $102,125 |

| EBIT | $71,250 | $76,594 |

| Interest | $— | $— |

| Taxes | $21,375 | $22,978 |

| Net profit | $49,875 | $53,616 |

Abbreviated Balance Sheet

| 2010 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total assets | $750,000 | $765,000 |

| Long-term debt | $— | $— |

| Owners’ equity | $750,000 | $765,000 |

| Total debt and equity | $750,000 | $765,000 |

ROA and ROE Values for 2010 and Projections for 2011

| 2010 (%) | 2011 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Return on assets | 6.65 | 7.01 |

| Return on equity | 6.65 | 7.01 |

After preparing these projections, the owners were approached by a company that manufactures computer-controlled machinery. The owners were presented with a series of machines that will not significantly raise the productive capacity of their business while also reducing the unit cost of production. The owners examined in detail the productive increase in improved efficiency that this computer-controlled machinery would provide. They estimated that demand in the market would increase if they had this new equipment, and sales could increase by 25 percent in 2011, rather than 7.5 percent as they had originally estimated. Further, the efficiencies brought about by the computer-controlled equipment would significantly reduce their operating costs. A rough estimate indicated that with this new equipment the cost of goods sold would decrease from 65 percent of revenue to 55 percent of revenue. These were remarkably attractive figures. The only reservation that the owners had was the cost of this new equipment. The sales price was $200,000, but the business did not have this amount of cash available. To raise this amount of money, they would either have to bring in a new equity partner who would supply the entire amount, borrow the $200,000 as a long-term loan, or have some combination of equity partnership and debt. They first approached a distant relative who has successfully invested in several businesses. This individual was willing to invest $50,000, $100,000, $150,000, or the entire $200,000 for taking an equity position in the firm. The owners also went to the bank where they had line of credit and asked about their lending options. The bank was impressed with the improved productivity and efficiency of the proposed new machinery. The bank was also willing to lend the business $50,000, $100,000, $150,000, or the entire $200,000 to purchase the computer-controlled equipment. The bank, however, stipulated that the lending rate would depend on the amount that was borrowed. If the firm borrowed $50,000, the interest rate would be 7.5 percent; if the amount borrowed was $100,000, the interest rate would increase to 10 percent; if $150,000 was the amount of the loan, the interest rate would be 12.5 percent; and if the firm borrowed the entire $200,000, the bank would charge an interest rate of 15 percent.

To correctly analyze this investment opportunity, the owners could employ several financial tools and methods, such as net present value (NPV). This approach examines a lifetime stream of additional earnings and cost savings for an investment. The cash flow that might exist is then discounted by the cost of borrowing that money. If the NPV is positive, then the firm should undertake the investment; if it is negative, the firm should not undertake the investment. This approach is too complex—for the needs of this text—to be examined in any detail. For the purpose of illustration, it will be assumed that the owners began by looking at the impact of alternative investment schemes on the projected results for 2011. Obviously, any in-depth analysis of this investment would have to entail multiyear projections.

They examined five scenarios:

- Their relative provides the entire $200,000 for an equity position in the business.

- They borrow $50,000 from the bank at an interest rate of 7.5 percent, and their relative provides the remaining $150,000 for a smaller equity position in the business.

- They borrow $100,000 from the bank at an interest rate of 10 percent, and their relative provides the remaining $100,000 for a smaller equity position in the business.

- They borrow $150,000 from the bank at an interest rate of 12.5 percent, and their relative provides the remaining $50,000 for an even smaller equity position in the business.

- They borrow the entire $200,000 from the bank at an interest rate of 15 percent.

The table below presents the income statement for these five scenarios. All five scenarios begin with the assumption that the new equipment would improve productive capacity and allow sales to increase, in 2011, by 25 percent, rather than the 7.5 percent that had been previously forecasted. Likewise, all five scenarios have the same cost of goods sold, which in this case is 55 percent of the revenues rather than the anticipated 65 percent if the new equipment is not purchased. All five scenarios have the same EBIT. The scenarios differ, however, in the interest payments. The first scenario assumes that all $200,000 would be provided by a relative who is taking an equity position in the firm. This is not a loan, so there are no interest payments. In the remaining four scenarios, the interest payments are a function of the amount borrowed and the corresponding interest rate. The payment of interest obviously impacts the earnings before taxes (EBT) and the amount of taxes that have to be paid. Although the tax bill for those scenarios where money has been borrowed is less than the scenario where the $200,000 is provided by equity, the net profit also declines as the amount borrowed increases.

Income Statement for the Five Scenarios

| Borrow $0 | Borrow $50,000 | Borrow $100,000 | Borrow $150,000 | Borrow $200,000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | $593,750 | $593,750 | $593,750 | $593,750 | $593,750 |

| Cost of goods sold | $326,563 | $326,563 | $326,563 | $326,563 | $326,563 |

| Gross profit | $267,188 | $267,188 | $267,188 | $267,188 | $267,188 |

| General sales and administrative | $118,750 | $118,750 | $118,750 | $118,750 | $118,750 |

| EBIT | $148,438 | $148,438 | $148,438 | $148,438 | $148,438 |

| Interest | $— | $3,750 | $10,000 | $18,750 | $30,000 |

| Taxes | $44,531 | $43,406 | $41,531 | $38,906 | $35,531 |

| Net profit | $103,906 | $101,281 | $96,906 | $90,781 | $82,906 |

Abbreviated Balance Sheet for the Five Scenarios

| Borrow $0 | Borrow $50,000 | Borrow $100,000 | Borrow $150,000 | Borrow $200,000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total assets | $965,000 | $965,000 | $965,000 | $965,000 | $965,000 |

| Long-term debt | $— | $50,000 | $100,000 | $150,000 | $200,000 |

| Owners’ equity | $965,000 | $915,000 | $865,000 | $815,000 | $765,000 |

| Total debt and equity | $965,000 | $965,000 | $965,000 | $965,000 | $965,000 |

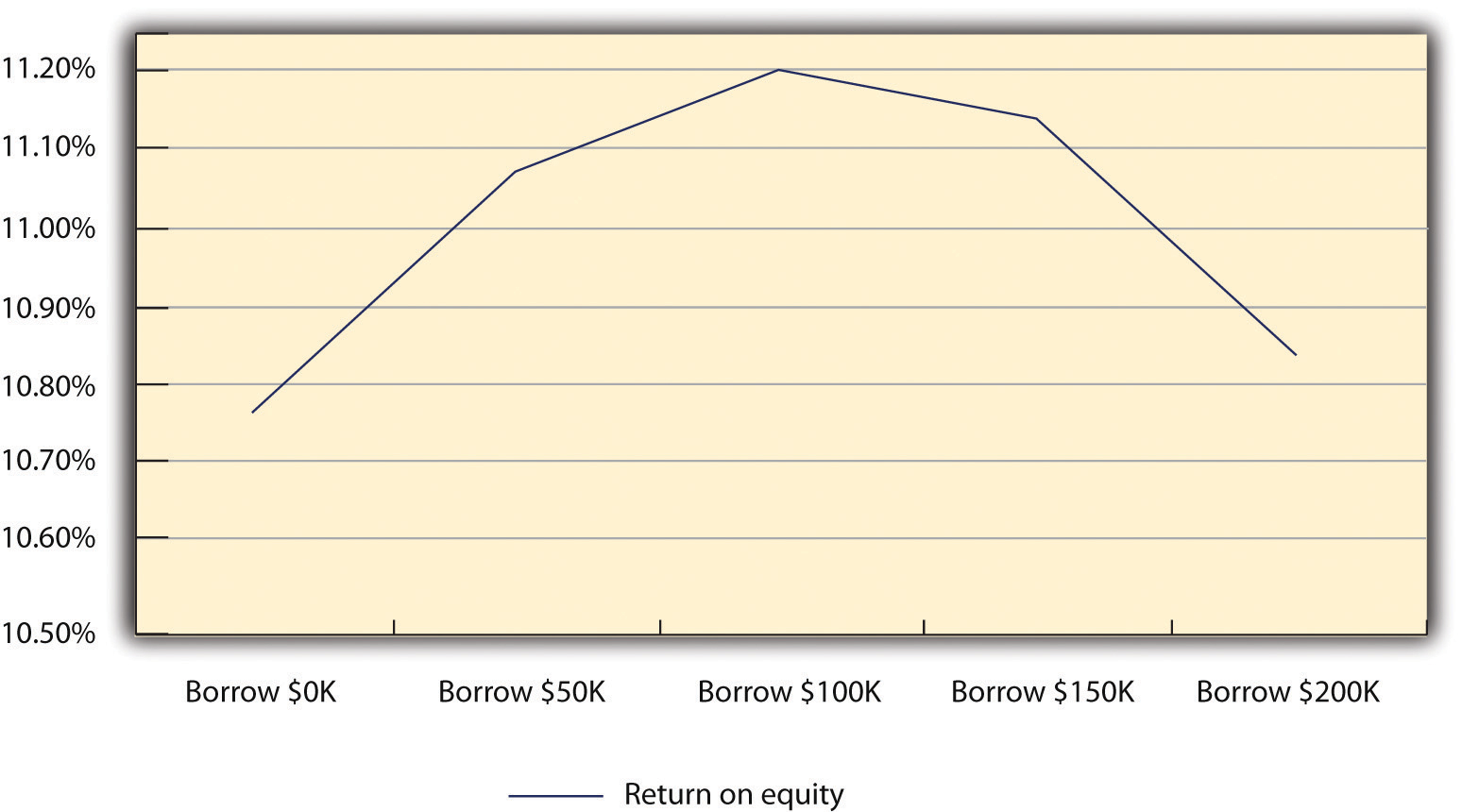

The owners then calculated the ROA and the ROE for the five scenarios. When they examined these results, they noticed that the greatest ROA occurred when the new machinery was financed exclusively by equity capital. The ROA declined as they began to fund new machinery with debt: the greater the debt, the lower the ROA. However, they saw a different situation when they looked at the ROE for each scenario. The ROE was greater in each scenario where the machinery was financed either exclusively or to some extent by debt. In fact, the lowest ROE (the firm borrowed the entire $200,000) was 50 percent higher than if the firm did not acquire the new equipment. A further examination of the ROE results provides a very interesting insight. The ROE increases as the firm borrows up to $100,000 of debt. When the firm borrows more money ($150,000 or $200,000), the ROE declines. This is a highly simplified example of optimal capital structure. There is a level of debt beyond which the benefits measured by ROE begins to decline. Small businesses must be able to identify their “ideal” debt-to-equity ratio.

ROA and ROE for the Five Scenarios

| Borrow $0 | Borrow $50,000 | Borrow $100,000 | Borrow $150,000 | Borrow $200,000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | 10.77% | 10.50% | 10.04% | 9.41% | 8.59% |

| ROE | 10.77% | 11.07% | 11.20% | 11.14% | 10.84% |

ROE for the Five Scenarios

The owners decided to carry their analysis one step further; they wondered if the sales projections were too enthusiastic. They were concerned about the firm’s ability to repay any loan should there be a drop in sales. Therefore, they decided to examine a worst-case scenario. Such analyses are absolutely critical if one is to fully evaluate the risk of undertaking debt. They ran the numbers to see what the results would be if there was a 25 percent decrease in sales in 2011 rather than a 25 percent increase in sales compared to 2010. The results of this set of analyses are in the following table. Even with a heavy debt burden for the five scenarios, the firm is able to generate a profit, although it is a substantially lower profit compared to if sales increased by 25 percent. They examined the impact of this proposed declining sales on ROA and ROE.

Income Statement for the Five Scenarios Assuming a 25 Percent Decrease in Sales

| Borrow $0 | Borrow $50,000 | Borrow $100,000 | Borrow $150,000 | Borrow $200,000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | $356,250 | $356,250 | $356,250 | $356,250 | $356,250 |

| Cost of goods sold | $195,938 | $195,938 | $195,938 | $195,938 | $195,938 |

| Gross profit | $160,313 | $160,313 | $160,313 | $160,313 | $160,313 |

| General sales and administrative | $71,250 | $71,250 | $71,250 | $71,250 | $71,250 |

| EBIT | $89,063 | $89,063 | $89,063 | $89,063 | $89,063 |

| Interest | $— | $3,750 | $10,000 | $18,750 | $30,000 |

| Taxes | $26,719 | $25,594 | $23,719 | $21,094 | $17,719 |

| Net profit | $62,344 | $59,719 | $55,344 | $49,219 | $41,344 |

ROA and ROE for the Five Scenarios under the Condition of Declining Sales

| Borrow $0 | Borrow $50,000 | Borrow $100,000 | Borrow $150,000 | Borrow $200,000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | 6.46% | 6.19% | 5.74% | 5.10% | 4.28% |

| ROE | 6.46% | 6.53% | 6.40% | 6.04% | 5.40% |

Key Takeaways

- A relatively simply model—breakeven analysis—can indicate what sales level is required to start making a profit.

- Financial leverage—the ratio of debt to equity—can improve the economic performance of a business as measured by ROE.

- Excessive financial leverage—too much debt—can begin to reduce the economic performance of a business.

- There is an ideal level of debt for a firm, which is its optimal capital structure.

- “Difference between Accounting and Finance,” DifferenceBetween.net, accessed February 1, 2012, www.differencebetween.net/business/difference-between -accounting-and-finance. ↵

- “Difference between Accounting and Finance,” DifferenceBetween.net, accessed February 1, 2012, www.differencebetween.net/business/difference-between -accounting-and-finance. ↵

- “Financing,” Small Business Notes, accessed December 2, 2011, www.smallbusinessnotes.com/business-finances/financing. ↵

- “Checklist: Issuing Stock,” San Francisco Chronicle, accessed December 2, 2011, allbusiness.sfgate.com/10809-1.html. ↵

- “How to Form a Corporation,” Yahoo! Small Business Advisor, April 26, 2011, accessed February 1, 2012, smallbusiness.yahoo.com/advisor/how-to-form-a-corporation -201616320.html. ↵

- “How Will a Credit Crunch Affect Small Business Finance?,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, March 6, 2009, accessed December 2, 2011, www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/letter/2009/el2009-09.html. ↵

- Anita Campbell, “Trade Credit: What It Is and Why You Should Pay Attention,” Small Business Trends, May 11, 2009, accessed December 2, 2011, smallbiztrends.com/2009/05/trade-credit-what-it-is-and-why-you-should-pay-attention.html. ↵

- Gavin Cassar, “The Financing of Business Startups,” Journal of Business Venturing 19 (2004): 261–83. ↵

- Lola Fabowale, Barbara Orse, and Alan Riding, “Gender, Structural Factors, and Credit Terms between Canadian Small Businesses and Financial Institutions,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 19 (1995): 41–65. ↵

- Harry Sapienza, M. Audrey Korsgaard, and Daniel Forbes, “The Self-Determination Mode of an Entrepreneur’s Choice of Financing,” in Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence, and Growth: Cognitive Approaches to Entrepreneurship Research, ed. Jerome A. Katz and Dean Shepherd (Oxford: Elsevier JAI, 2003) 6:105–38. ↵

- Allen N. Berger and Gregory F. Udell, “The Economics of Small Business Finance: The Roles of Private Equity and Debt Markets in the Financial Growth Cycle,” Journal of Banking and Finance 22, no. 6–8 (1998): 613–73. ↵

- Rowena Ortiz-Walters and Mark Gius, “Performance of Newly Formed Micro Firms: The Role of Capital Financing Structure and Entrepreneurs’ Personal Characteristics” (unpublished manuscript), 2011. ↵

- “The Benefits of Making Your Banker Your Friend,” Small Business Administration, accessed December 2, 2011, www.sbaonline.sba.gov./smallbusinessplanner/start/financestartup/SERV_BANKERFRIEND.html. ↵

- “Breakeven Analysis: Know When You Can Expect a Profit,” Small Business Administration, accessed December 2, 2011, www.sba.gov/content/breakeven-analysis -know-when-you-can-expect-profit. ↵

- David Durand, “Cost of Debt and Equity Funds for Business: Trends and Problems of Measurement,” Conference on Research in Business Finance (New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1952), 220. ↵

- Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, “The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment,” American Economic Review 48, no. 3 (1958): 261–97; Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, “Taxes and the Cost of Capital: A Correction,” American Economic Review 53 (1963): 433–43. ↵

The science of money management that consists of financial planning, financial control, and financial decision making.

The proportion of a firm that is financed by debt and by equity.

An acronym used by bankers to describe factors that they consider when evaluating a loan: character, ability, means, purpose, amount, repayment, and insurance.

Used to determine the amount of sales volume a company needs to start making a profit: when its total sales or revenues equal its total expenses.

The weighted average of a firm’s debt and equity, where equity is directly related to the firm’s stock.

A value that discounts the value of future cash flows. It recognizes the time value of money.