5 Chapter 5 – The Business Plan

Developing Your Strategy

As mentioned in Chapter 2, it is critically important for any business organization to be able to accurately understand and identify what constitutes customer value. To do this, one must have a clear idea of who your customers are or will be. However, simply identifying customer value is insufficient. An organization must be able to provide customer value within several important constraints. One of these constraints deals with the competition—what offerings are available and at what price. Also, what additional services might a company provide? A second critically important constraint is the availability of resources to the business organization. Resources consist of factors such as money, facilities, equipment, operational capability, and personnel.

Here is an example: a restaurant identified its prime customer base as being upscale clientele in the business section of a major city. The restaurant recognized that it has numerous competitors that are interested in providing the same clientele with an upscale dining experience. Our example restaurant might provide a five-course, five-star gourmet meal to its customers. It also provides superlative service. If a comparable restaurant failed to provide a comparable meal than the example restaurant, the example restaurant would have a competitive advantage. If the example restaurant offered these sumptuous meals for a relatively low price in comparison to its competitors, it would initially seem to have even more of an advantage. However, if the price charged is significantly less than the cost of providing the meal, the service in this situation could not be maintained. In fact, the restaurant inevitably would have to go out of business. Providing excellent customer service may be a necessary condition for business survival but, in and of itself, it is not a sufficient condition.

So how does one go about balancing the need to provide customer value within the resources available while always maintaining a watchful eye on competitors’ actions? We are going to argue that what is required for that firm is to have a strategy.

The word strategy is derived from the Greek word strategos, which roughly translates into the art of the general, namely a military leader. Generals are responsible for marshaling required resources and organizing the troops and the basic plan of attack. Much in the same way, executives as owners of businesses are expected to have a general idea of the desired outcomes, acquire resources, hire and train personnel, and generate plans to achieve those outcomes. In this sense, all businesses, large and small, have strategies, whether they are clearly written out in formal business plans or reside in the mind of the owner of the business.

There are many different formal definitions of strategy with respect to business. The following is a partial listing of some of the definitions given by key experts in the field:

“A strategy is a pattern of objectives, purposes or goals and the major policies and plans for achieving these goals, stated in such a way as to define what business the company is in or is to be in and the kind of company it is or to be.”[1]

“The determination of the long-run goals and objectives of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals.”[2]

“What business strategy is all about, in a word, is competitive advantage.”[3]

We define the strategy of a business as follows: A firm’s strategy is the path by which it seeks to provide its customers with value, given the competitive environment and within the constraints of the resources available to the firm.

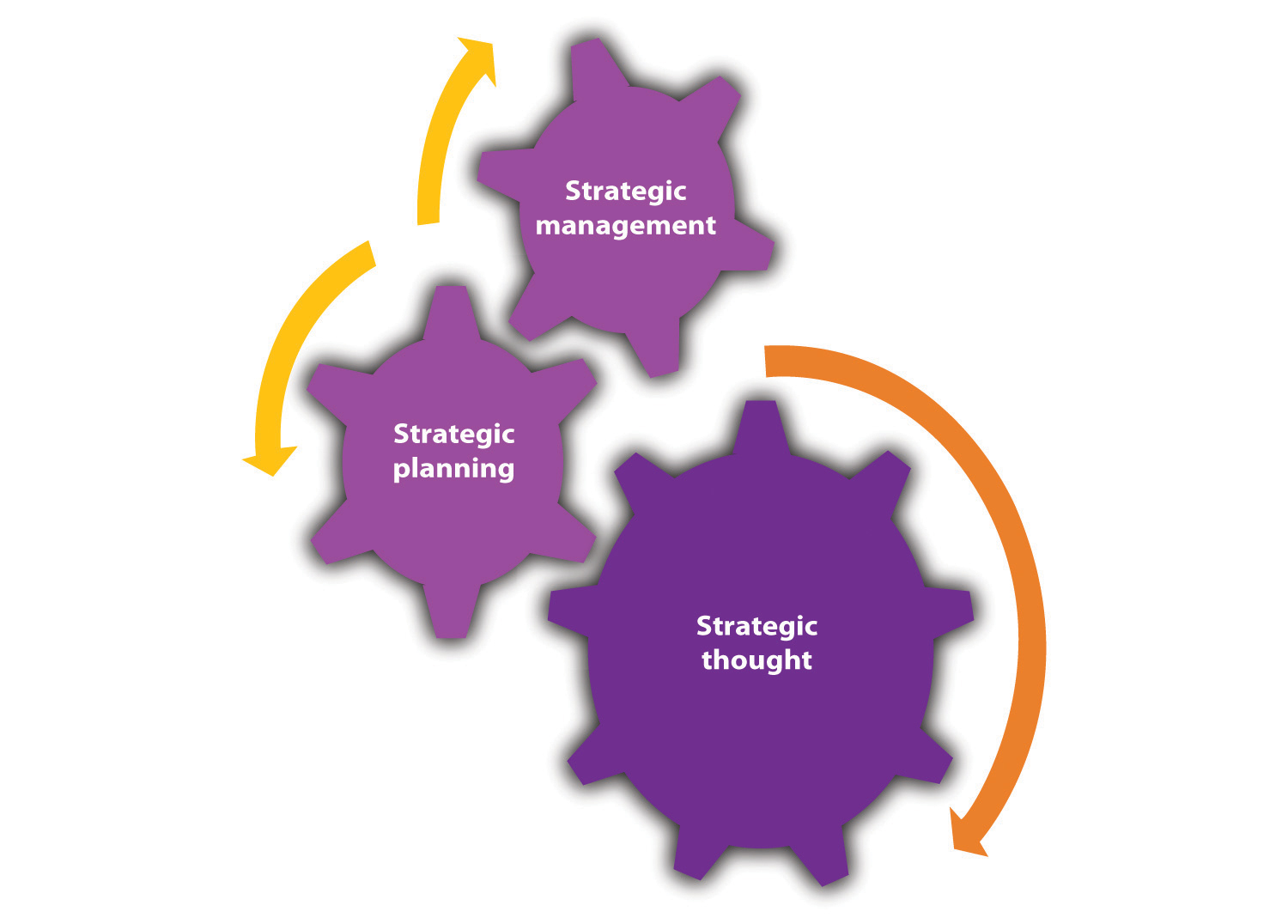

Whatever definition of strategy is used, it is often difficult to separate it from two other terms: strategic planning and strategic management. Both terms are often perceived as being in the domain of large corporations, not necessarily small to midsize businesses. This is somewhat understandable. The origin of strategic planning as a separate discipline occurred over fifty years ago. It was mainly concerned with assisting huge multidivisional or global businesses in coordinating their activities. In the intervening half-century, strategic planning has produced a vast quantity of literature. Mintzberg, Lampel, Ahlstrand, in a highly critical review of the field, identified ten separate schools associated with strategic planning.[4] With that number of different schools, it is clear that the discipline has not arrived at a common consensus. Strategic planning has been seen as a series of techniques and tools that would enable organizations to achieve their specified goals and objectives. Strategic management was seen as the organizational mechanisms by which you would implement the strategic plan. Some of the models and approaches associated with strategic planning and strategic management became quite complex and would prove to be fairly cumbersome to implement in all but the largest businesses. Further, strategic planning often became a bureaucratic exercise where people filled out forms, attended meetings, and went through the motions to produce a document known as the strategic plan. Sometimes what is missed in this discussion was a key element—strategic thinking. Strategic thinking is the creative analysis of the competitive landscape and a deep understanding of customer value. It should be the driver (see “Strategy Troika”) of the entire process. This concept is often forgotten in large bureaucratic organizations.

Strategy Troika

Strategic thinkers often break commonly understood principles to reach their goals. This is most clearly seen among military leaders, such as Alexander the Great or Hannibal. Robert E. Lee often violated basic military principles, such as dividing his forces. General Douglas MacArthur shocked the North Koreans with his bold landings behind enemy lines at Inchon. This mental flexibility also exists in great business leaders.

Solomon and Friedman recounted a prime example of true strategic thinking.[5] Wilson Harrell took a small, closely held, cleaning spray company known as Formula 409 to the point of having national distribution. In 1967, the position that Formula 409 held was threatened by the possible entry of Procter & Gamble into the same spray cleaning market. Procter & Gamble was a huge consumer products producer, noted for its marketing savvy. Procter & Gamble began a program of extensive market research to promote its comparable product they called Cinch. Clearly, the larger firm had a much greater advantage. Harrell knew that Procter & Gamble would perform test market research. He decided to do the unexpected. Rather than directly confront this much larger competitor, he began a program where he reduced advertising expenditures in Denver and stopped promoting his Formula 409. The outcome was that Procter & Gamble had spectacular results, and the company was extremely excited with the potential for Cinch. Procter & Gamble immediately begin a national sales campaign. However, before the company could begin, Harrell introduced a promotion of his own. He took the Formula 409 sixteen-ounce bottle and attached it to a half-gallon size bottle. He then sold both at a significant discount. This quantity of spray cleaner would last the average consumer six to nine months. The market for Procter & Gamble’s Cinch was significantly reduced. Procter & Gamble was confused and confounded by its poor showing after the phenomenal showing in Denver. Confused and uncertain, the company chose to withdraw Cinch from the market. Wilson Harrell’s display of brilliant strategic thinking had bested them. He leveraged his small company’s creative thinking and flexibility against the tremendous resources of an international giant. Through superior strategic thinking, Harrell was able to best Procter & Gamble.

Do You Have a Strategy and What Is It?

We have argued that all businesses have strategies, whether they are explicitly articulated or not. Perry stated that “small business leaders seem to recognize that the ability to formulate and implement an effective strategy has a major influence on the survival and success of small business.”[6]

The extent to which a strategy should be articulated in a formal manner, such as part of a business plan, is highly dependent on the type of business. One might not expect a formally drafted strategy statement for a nonemployee business funded singularly by the owner. One researcher found that formal plans are rare in businesses with fewer than five employees.[7] However, you should clearly have that expectation for any other type of small or midsize business.

Any business with employees should have an articulated strategy that can be conveyed to them so that they might better assist in implementing it. Curtis pointed out that in the absence of such communication, “employees make pragmatic short-term decisions that cumulatively form an ad-hoc strategy.”[8] These ad hoc (realized) strategies may be at odds with the planned (intended) strategies to guide a firm.[9] However, any business that seeks external funding from bankers, venture capitalists, or “angels” must be able to specify its strategy in a formal business plan.

Clearly specifying your strategy should be seen as an end in itself. Requiring a company to specify its strategy forces that company to think about its core issues, such as the following:

- Who are your customers?

- How are you going to provide value to those customers?

- Who are your current and future competitors?

- What are your resources?

- How are you going to use these resources?

One commentator in a blog put it fairly well, “It never ceases to amaze me how many people will use GPS or Google maps for a trip somewhere but when it comes to starting a business they think that they can do it without any strategy, or without any guiding road-map.” Harry Tucci, comment posted to the following blog:[10]

Types of Strategies

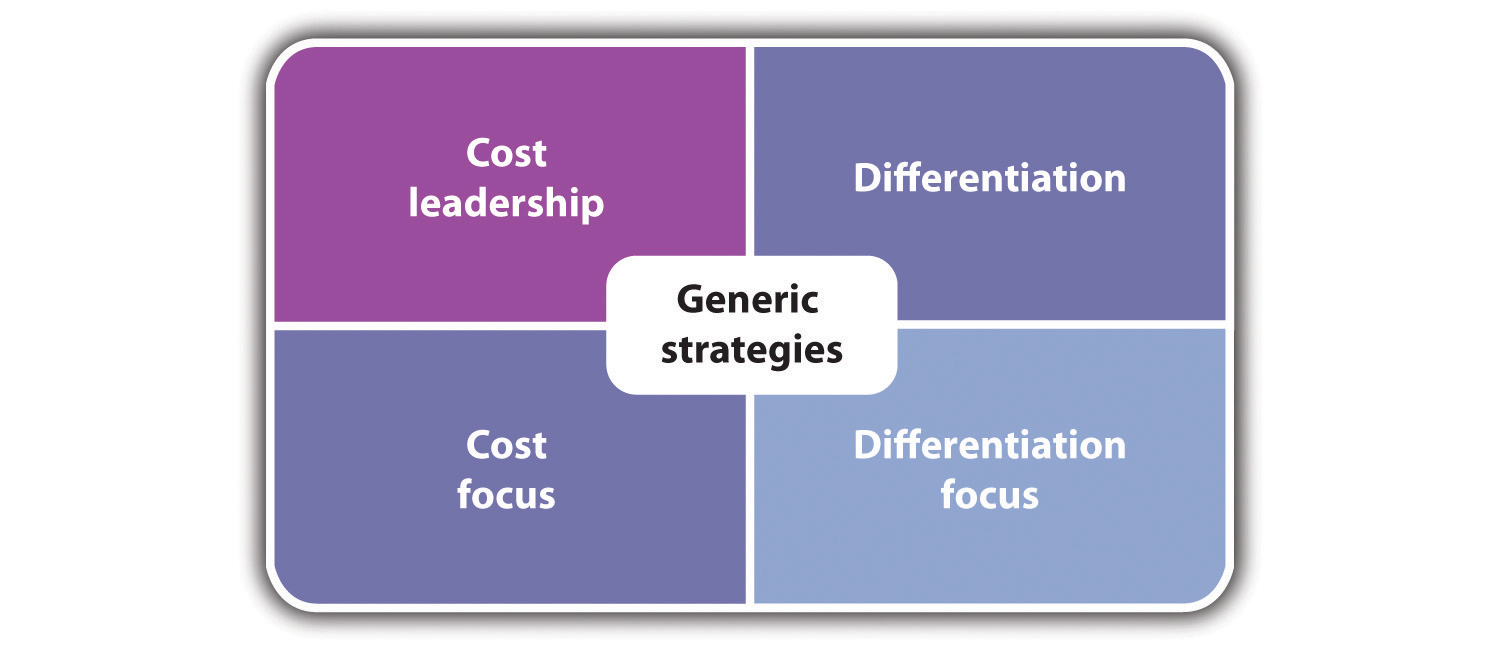

In 1980, Michael Porter a professor at Harvard Business School published a major work in the field of strategic analysis—Competitive Strategy.[11] To simplify Porter’s thesis, while competition is beneficial to customers, it is not always beneficial to those who are competing. Competition may involve lowering prices, increasing research and development (R&D), and increasing advertising and other expenses and activities—all of which can lower profit margins. Porter suggested that firms should carefully examine the industry in which they are operating and apply what he calls the five forces model. These five forces are as follows: the power of suppliers, the power of buyers, the threat of substitution, the threat of new entrants, and rivalry within the industry. We do not need to cover these five forces in any great detail, other than to say that once the analysis has been conducted, a firm should look for ways to minimize the dysfunctional consequences of competition. Porter identified four generic strategies that firms may choose to implement to achieve that end. Actually, he initially identified three generic strategies, but one of them can be bifurcated. These four strategies are as follows (see “Generic Strategies”): cost leadership, differentiation, cost focus, and differentiation focus. These four generic strategies can be applied to small businesses. We will examine each strategy and then discuss what is required to successfully implement them.

Generic Strategies

Low-Cost Advantage

A cost leadership strategy requires that a firm be in the position of being the lowest cost producer in its competitive environment. By being the lowest-cost producer, a firm has several strategic options open to it. It can sell its product or service at a lower price than its competitors. If price is a major driver of customer value, then the firm with the lowest price should sell more. The low-cost producer also has the option of selling its products or services at prices that are comparable to its competitors. However, this would mean that the firm would have a much higher margin than its competitors.

Obviously, following a cost leadership strategy dictates that the business be good at curtailing costs. Perhaps the clearest example of a firm that employs a cost leadership strategy is Walmart. Walmart’s investment in customer relations and inventory control systems plus its huge size enables it to secure the “best” deals from suppliers and drastically reduce costs. It might appear that cost leadership strategies are most suitable for large firms that can exploit economies of scale. This is not necessarily true. Smaller firms can compete on the basis of cost leadership. They can position themselves in low-cost areas, and they can exploit their lower overhead costs. Family businesses can use family members as employees, or they can use a web presence to market and sell their goods and services. A small family-run luncheonette that purchases used equipment and offers a limited menu of standard breakfast and lunch items while not offering dinner might be good example of a small business that has opted for a cost leadership strategy.

Differentiation

A differentiation strategy involves providing products or services that meet customer value in some unique way. This uniqueness may be derived in several ways. A firm may try to build a particular brand image that differentiates itself from its competitors. Many clothing lines, such as Tommy Hilfiger, opt for this approach. Other firms will try to differentiate themselves on the basis of the services that they provide. Dominoes began to distinguish itself from other pizza firms by emphasizing the speed of its delivery. Differentiation also can be achieved by offering a unique design or features in the product or the service. Apple products are known for their user-friendly design features. A firm may wish to differentiate itself on the basis of the quality of its product or service. Kogi barbecue trucks operating in Los Angeles represent such an approach. They offer high-quality food from mobile food trucks.”[12] They further facilitate their differentiation by having their truck routes available on their website and on their Twitter account.

Adopting a differentiation strategy requires significantly different capabilities than those that were outlined for cost leadership. Firms that employ a differentiation strategy must have a complete understanding of what constitutes customer value. Further, they must be able to rapidly respond to changing customer needs. Often, a differentiation strategy involves offering these products and services at a premium price. A differentiation strategy may accept lower sales volumes because a firm is charging higher prices and obtaining higher profit margins. A danger in this approach is that customers may no longer place a premium value on the unique features or quality of the product or the service. This leaves the firm that offers a differentiation strategy open to competition from those that adopt a cost leadership strategy.

Focus—Low Cost or Differentiation

Porter identifies the third strategy—focus. He said that focus strategies can be segmented into a cost focus and a differentiation focus.

In a focus strategy, a firm concentrates on one or more segments of the overall market. Focus can also be described as a niche strategy. Focus strategy entails deciding to some extent that we do not want to have everyone as a customer. There are several ways that a firm can adopt a focus perspective:

- Product line. A firm limits its product line to specific items of only one or more product types. California Cart Builder produces only catering trucks and mobile kitchens.

- Customer. A firm concentrates on serving the needs of a particular type of customer. Weight Watchers concentrates on customers who wish to control their weight or lose weight.

- Geographic area. Many small firms, out of necessity, will limit themselves to a particular geographic region. Microbrewers generally serve a limited geographic region.

- Particular distribution channel. Firms may wish to limit themselves with respect to the means by which they sell their products and services. Amazon began and remains a firm that sells only through the Internet.

Firms adopting focus strategies look for distinct groups that may have been overlooked by their competitors. This group needs to be of sufficiently sustainable size to make it an economically defensible option. One might open a specialty restaurant in a particular geographic location—a small town. However, if the demand is not sufficiently large for this particular type of food, then the restaurant will probably fail. Companies that lack the resources to compete on either a national level or an industry-wide level may adopt focus strategies. Focus strategies enable firms to marshal their limited resources to best serve their customers.

As previously stated, focus strategies can be bifurcated into two directions—cost focus or differentiation focus. IKEA sells low-priced furniture to those customers who are willing to assemble the furniture. It cuts its costs by using a warehouse rather than showroom format and not providing home delivery. Michael Dell began his business out of his college dormitory. He took orders from fellow students and custom-built computers to their specifications. This was a cost focus strategy. By building to order, it almost totally eliminated the need for any incoming, work-in-process, or finished goods inventories.

A focus differentiation strategy concentrates on providing a unique product or service to a segment of the market. This strategy may be best represented by many specialty retail outlets. The Body Shop focuses on customers who want natural ingredients in their makeup. Max and Mina is a kosher specialty ice cream store in New York City. It provides a constantly rotating menu of more than 300 exotic flavors, such as Cajun, beer, lox, corn, and pizza. The store has been written up in the New York Times and People magazine. Given its odd flavors, Max and Mina’s was voted the number one ice cream parlor in America in 2004.[13]

Evaluating Strategies

The selection of a generic strategy by a firm should not be seen as something to be done on a whim. Once a strategy is selected, all aspects of the business must be tied to implementing that strategy. As Porter stated, “Effectively implementing any of these generic strategies usually requires total commitment and supporting organizational arrangements.”[14] The successful implementation of any generic strategy requires that a firm possess particular skills and resources. Further, it must impose particular requirements on its organization (see “Summary of Generic Strategies”).

Even successful generic strategies must recognize that market and economic conditions change along with the needs of consumers. Henry Ford used a cost leadership strategy and was wildly successful until General Motors began to provide different types of automobiles to different customer segments. Likewise, those who follow a differentiation strategy must be cautious that customers may forgo “extras” in a downturn economy in favor of lower costs. This requires businesses to be vigilant, particularly with respect to customer value.

Summary of Generic Strategies

| Generic Strategy | Required Activities | Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Cost leadership |

|

|

| Differentiation |

|

|

| Focus—low cost |

|

|

| Focus—differentiation |

|

|

Key Takeaways

- Any firm, regardless of size, needs to know how it will compete; this is the firm’s strategy.

- Strategy identifies how a firm will provide value to its customers within its operational constraints.

- Strategy can be reduced to four major approaches—cost leadership, differentiation, cost focus, and differentiation focus.

- Once a given strategy is selected, all of a firm’s operations should be geared to implementing that strategy.

- No strategy will be successful forever and therefore needs to be constantly evaluated.

The Necessity for a Business Plan

An intelligent plan is the first step to success. The man who plans knows where he is going, knows what progress he is making and has a pretty good idea of when he will arrive. Planning is the open road to your destination. If you don’t know where you’re going, how can you expect to get there? – Basil Walsh

In Chapter 1, we discussed the issue of failure and small businesses. Although research on small business failure has identified many factors, one reason that always appears at the top of any list is the failure to plan. Interestingly, some people argue that planning is not essential for a start-up business, but they are in a distinct minority.[15] The overwhelming consensus is that a well-developed plan is essential for the survival of any small (or large) business.[16] Perry found that firms with more than five people benefit from having a well-developed business plan.[17]

A recent study found that there was a near doubling of successful growth for those businesses that completed business plans compared to those that did not create one. It must be pointed out that this study might be viewed as being biased because the founder of the software company whose main product is a program that builds business plans conducted the study. However, the results were examined by academics from the University of Oregon who validated the overall results. They found that “except in a small number of cases, business planning appeared to be positively correlated with business success as measured by our variables. While our analysis cannot say the completing of a business plan will lead to success, it does indicate that the type of entrepreneur who completes a business plan is also more likely to produce a successful business.”[18]

Basically, there are two main reasons for developing a comprehensive business plan: (1) a plan will be extraordinarily useful in ensuring the successful operation of your business; and (2) if one is seeking to secure external funds from banks, venture capitalists, or other investors, it is essential that you be able to demonstrate to them that they will be recovering their money and making a profit. Let us examine each reason in detail.

Many small business owners operate under a mistaken belief that the only time that they need to create a business plan is at the birth of the company or when they are attempting to raise additional capital from external sources. They fail to realize that a business plan can be an important element in ensuring day-to-day success.

The initial planning process aids the operational success of a small business by allowing the owner a chance to review, in detail, the viability of the business idea. It forces one to rigorously consider some key questions:

- Is the business strategy feasible?

- What are the chances it will make money?

- Do I have the operational requirements for starting and running a successful business?

- Have I considered a well-thought-out marketing plan that clearly identifies who my customers will be?

- Do I clearly understand what value I will provide to these customers?

- What will be the means of distribution to provide the product or the service to my customers?

- Have I clarified to myself the financial issues associated with starting and operating the business?

- Do I have to reexamine these notions to ensure success?

Possessing an actual written plan enables you to have people outside the organization evaluate your business plan. Using friends, colleagues, partners, or even consultants may provide you with an unbiased evaluation of the assumptions.

It is not enough to create an initial business plan; you should anticipate making the planning process an annual activity. The Prussian military theorist von Moltke once argued that no military plan survives the first engagement with the enemy. Likewise, no company evolves in the same way as outlined in its initial business plan.

Overcoming the Reluctance to Formally Plan

By failing to prepare, you will prepare them to fail. -Benjamin Franklin

Unfortunately, it appears that many small businesses do not make any effort to build even an initial business plan, let alone maintain a planning process as an ongoing operation, even though there is clear evidence that the failure to plan may have serious consequences for the future success of such firms. This unwillingness to plan may be understandable in nonemployee businesses, but it is inexcusable as a business grows in size. Why, therefore, do some businesses fail to begin the planning process?

- We do not need to plan. One of the prime reasons individuals fail to produce a business plan is that they believe that they do not have to plan. This may be attributable to the size of the firm; nonemployee firms that have no intention of seeking outside financing might sincerely believe that they have no need for a formal business plan. Others may believe that they so well understand the business and/or industry that they can survive and prosper without the burdensome process of a business plan. The author of Business Plan for Dummies, Paul Tiffany, once argued that if one feels lucky enough to operate a business successfully without resorting to a business plan, then he or she should forget about starting a business and head straight to Las Vegas.

- I am too busy to plan. Anyone who has ever run a business on his or her own can understand this argument. The day-to-day demands of operating a business may make it seem that there is insufficient time to engage in any ancillary activity or prepare a business plan. Individuals who accept this argument often fail to recognize that the seemingly endless buzz of activities, such as constantly putting out fires, may be the direct result of not having thought about the future and planned for it in the first place.

- Plans do not produce results. Small-business owners (entrepreneurs) are action- and results-oriented individuals. They want to see a tangible outcome for their efforts, and preferably they would like to see the results as soon as possible. The idea of sitting down and producing a large document based on assumptions that may not play out exactly as predicted is viewed as a futile exercise. However, those with broader experience understand that there will be no external funding for growth or the initial creation of the business without the existence of a well-thought-out plan. Although plans may not yield the specified results contained within them, the process of thinking about the plan and building it often yield results that the owner might not initially appreciate.

- We are not familiar with the process of formal planning. This argument might initially appear to have more validity than the others. Developing a comprehensive business plan is a daunting task. It might seem difficult if not impossible for someone with no experience with the concept. Several studies have indicated that small business owners are more likely to engage in the planning process if they have had prior experience with planning models in their prior work experience.[19] Fortunately, this situation has changed rather significantly in the last decade. As we will illustrate, there are numerous tools that provide significant support for the development of business plans. We will see that software packages greatly facilitate the building of any business plan, including marketing plans and financial plans for small businesses. We also show that the Internet can provide an unbelievably rich source of data and information to assist in the building of these plans.

Although one could understand the reticence of someone new to small business (or in some cases even seasoned entrepreneurs), their arguments fall short with respect to the benefits that will be derived from conducting a structured and comprehensive business planning process.

Plans for Raising Capital

Every business plan should be written with a particular audience in mind. The annual business plan should be written with a management team and for the employees who have to implement the plan. However, one of the prime reasons for writing a business plan is to secure investment funds for the firm. Of course, funding the business could be done by an individual using his or her own personal wealth, personal loans, or extending credit cards. Individuals also can seek investments from family and friends. The focus here will be on three other possible sources of capital—banks, venture capitalists, and angel investors. It is important to understand what they look for in a business plan. Remember that these three groups are investors, so they will be anticipating, at the very least, the ability to recover their initial investment if not earn a significant return.

Bankers

Bankers, like all businesspeople, are interested in earning a profit; they want to see a return on their investment. However, unlike other investors, bankers are under a legal obligation to ensure that the borrower pledge some form of collateral to secure the loan.[20] This often means that banks are unwilling to fund a start-up business unless the owner is willing to pledge some form of collateral, such as a second mortgage on his or her home. Many first-time business owners are not in a position to do that; securing money from a bank occurs most frequently for an existing business that is looking to expand or for covering a short-term cash-flow need. Banks may lend to small business owners who are opening a second business provided that they can prove a record of success and profitability.

Banks will require a business plan. It should be understood that bank loan officers will initially focus on the financial components of that client, namely, the income statement, balance sheet, and the cash-flow statement. The bank will examine your projections with respect to known industry standards. Therefore, the business plan should not project a 75 percent profit margin when the industry standard is 15 percent, unless the author of the plan can clearly document why he or she will be earning such a high return.

Some businesses may raise funds with the assistance of a Small Business Administration (SBA) loan. These loans are always arranged through a commercial bank. With these loans, the SBA will pledge up to 70 percent of the total value of the loan. This means that the owner still must provide, at the very least, 30 percent of the total collateral. The ability to secure one of these loans is clearly tied to the adequacy of the business plan.

Venture Capitalists

Another possible source of funding is venture capitalists. The first thing that one should realize about venture capitalists is that they are not in it just to make a profit; they want to make returns that are substantially above those to be found in the market. For some, this translates into the ability to secure five to ten times their initial investment and recapture their investment in a relatively short period of time—often less than five years. It has been reported that some venture capitalists are looking for returns in the order of twenty-five times their original investment.[21]

The financial statement, particularly the profit margin, is obviously important to venture capitalists, but they will also be looking at other factors. The quality of the management team identified in the business plan will be examined. They will be looking at the team’s experience and track record. Other factors needed by venture capitalists may include the projected growth rate of the market, the extent to which the product or the service being offered is unique, the overall size of the market, and the probability of producing a highly successful product or service.

Businesses that are seeking financing from banks know that they must go to loan officers who will review the plan, even though a computerized loan assessment program may make the final decision. With venture capitalists, on the other hand, you often need to have a personal introduction to have your plan considered. You should also anticipate that you will have to make a presentation to venture capitalists. This means that you have to understand your plan and be able to present it in a dynamic fashion.

Angel Investors

The third type of investor is referred to as angel investors, a term that originally came from those individuals who invested in Broadway shows and films. Many angel investors are themselves successful entrepreneurs. As with venture capitalists, they are looking for returns higher than they can normally find in the market; however, they often expect returns lower than those anticipated by venture capitalist. They may be attracted to business plans because of an innovative concept or the excitement of entering a new type of business. Being successful small business owners, many angel investors will not only provide capital to fund the business but also bring their own expertise and experience to help the business grow. It has been estimated that these angel investors provide between three and ten times as much money as venture capitalists for the development of small businesses.[22]

Angel investors will pay careful attention to all aspects of the proposed business plan. They expect a comprehensive business plan—one that clearly specifies the future direction of the firm. They also will look at the management team not only for its track record and experience but also their (the angel investor’s) ability to work with this team. Angel investors may take a much more active role in the management of the business, asking for positions on the board of directors, taking an equity position in the firm, demanding quarterly reports, or demanding that the business not take certain actions unless it has the approval of these angel investors. These investors will take a much more hands-on approach to the operations of a firm.

Key Takeaways

- Planning is a critical and important component of ensuring the success of a small business.

- Some form of formal planning should not only accompany the start-up of a business but also be a regular (annual) activity that guides the future direction of the business.

- Many small business owners are reluctant to formally plan. They can produce many excuses for not planning.

- Businesses may have to raise capital from external sources—bankers, venture capitalists, or angel investors. Each type of investor will expect a business plan. Each type of investor will be more or less interested in different parts of the plan. Business owners should be aware of what parts of the plan each type of investor will focus on.

Building a Plan

Before talking about writing a formal business plan, someone interested in starting a business might want to think about doing some personal planning before drafting the business plan. Some of the questions that he or she might want to answer before drafting a full business plan are as follows:

- Why am I going into this business?

- What skills and resources do I possess that will help make the business a success?

- What passion do I bring to this business?

- What is my risk tolerance?

- Exactly how hard do I intend to work? How many hours per week?

- What impact will the business have on my family life?

-

What do I really wish from this business?

- Am I interested in financial independence?

- What level of profits will be required to maintain my personal and/or family’s lifestyle?

- Am I interested in independence of action (no boss but myself)?

- Am I interested in personal satisfaction?

- Will my family be working in this business?

- What other employees might I need?[23]

Having addressed these questions, one will be in a much better position to craft a formal business plan.

Gathering Information

Building a solid business plan requires knowing the economic, market, and competitive environments. Such knowledge transcends “gut feelings” and is based on data and evidence. Fortunately, much of the required information is available through library resources, Internet sources, and government agencies and, for a fee, from commercial sources. Comprehensive business plans may draw from all these sources.

Public libraries and those at educational institutions provide a rich resource base that can be used at no cost. Some basic research sources that can be found at libraries are given in this section—be aware that the reference numbers provided may differ from library to library.

Library Sources

Background Sources

- Berinstein, Paula. Business Statistics on the Web: Find Them Fast—At Little or No Cost (Ref HF1016 .B47 2003).

- The Core Business Web: A Guide to Information Resources (Ref HD30.37 .C67 2003).

- Frumkin, Norman. Guide to Economic Indicators, 4th ed. (Ref HC103 .F9 2006). This book explains the meanings and uses of the economic indicators.

- Solie-Johnson, Kris. How to Set Up Your Own Small Business, 2 volumes (Ref HD62.7 .S85 2005). Published by the American Institute of Small Business.

Company and Industry Sources

- North American Industry Classification System, United States (NAICS), 2007 (Ref HF1042 .N6 2007). The NAICS is a numeric industry classification system that replaced the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) system. An electronic version is available from the US Census Bureau.

- Standard Industrial Classification Manual (Ref HA40 .I6U63 1987). The industry classification system that preceded the NAICS.

- Value Line Investment Survey (Ref HG4751 .V18). Concise company and industry profiles are updated every thirteen weeks.

Statistical Sources

- Almanac of Business and Industrial Financial Ratios (Ref HF5681 .R25A45 2010).

- Business Statistics of the United States (Ref HC101 .A13123 2009). This publication provides recent and historical information about the US economy.

- Economic Indicators (1971–present). The Council of Economic Advisers for the Joint Economic Committee of Congress publishes this monthly periodical; recent years are in electronic format only. Ten years of data are presented. Electronic versions are available in ABI/INFORM and ProQuest from September 1994 to present and Academic OneFile from October 1, 1991.

- Industry Norms and Key Business Ratios (Dun & Bradstreet; Ref HF5681 .R25I532 through Ref HF5681 .I572 [2000–2001 through 2008–2009]).

- Rma Annual Statement Studies (Ref HF5681 .B2R6 2009–2010). This publication provides annual financial data and ratios by industry.

- Statistical Abstract of the United States (Ref HA202 .S72 2010). This is the basic annual source for statistics collected by the government. Electronic version is available at www.census.gov/compendia/statstatab.

- Survey of Current Business (1956–present). The Bureau of Economic Analysis publishes this monthly periodical; recent years are in electronic format only.

At some libraries, you may find access to the following resources online:

- Mergent Webreports. Mergent (formerly Moody’s) corporate manuals are in digitized format. Beginning with the early 1900s, the reports include corporate history, business descriptions, and in-depth financial statements. The collection is searchable by company name, year, or manual type.

- ProQuest Direct is a database of general, trade, and scholarly periodicals, with many articles in full text. Many business journals and other resources are available.

- Standard and Poor’s Netadvantage is a database that includes company and industry information.

Internet Resources

In addition to government databases and other free sources, the Internet provides an unbelievably rich storehouse of information that can be incorporated into any business plan. It is not feasible to provide a truly comprehensive list of useful websites; this section provides a highly selective list of government sites and other sites that provide free information.

Government Sites

- US Small Business Administration (SBA). This is an excellent site to begin researching a business plan. It covers writing a plan, financing a start-up, selecting a location, managing employees, and insurance and legal issues. A follow-up page at http://www.sba.gov provides access to publications, statistics, video tutorials, podcasts, business forms, and chat rooms. Another page—http://www.sba.gov/about-offices-list/2—provides access to localized resources.

- SCORE Program. The SCORE program is a partner of the SBA. It provides a variety of services to small business owners, ranging from online (and in-person) mentoring, workshops, free computer templates, and advice on a wide range of small business issues.

In developing a business plan, it is necessary to anticipate the future economic environment. The government provides extensive statistics online.

- Consumer Price Index. This index provides information on the direction of prices for industries and geographic areas.

- Producer Price Index. Businesses that provide services or are focused on business-to-business (B2B) operations may find these data more appropriate for estimating future prices.

- National Wage Data. This site provides information on prevailing wages and can be broken down by occupation and location down to the metropolitan area.

- Consumer Expenditures Survey. This database provides information on expenditures and income. It allows for a remarkable level of refinement by occupation, age, or race.

- State and Local Personal Income and Employment. These databases provide a breakdown of personal income by state and metropolitan area.

- GDP by State and Metropolitan Region. This will provide an accurate guide to the overall economic health of a region or a city.

- US Census. This is a huge site with databases on population, income, foreign trade, economic indicators, and business ownership.

There are nongovernment websites, either free or charging a fee, that can provide assistance in building a business plan. A simple Google search for the phrase small business plan yields more than 67 million results. Various sites will either help with writing the plan, offer to write the plan for a fee, produce reports on industries, or assist small businesses by providing a variety of support services. The Internet offers a veritable cornucopia of information and support for those working on their business plans.

Forecasting for the Plan

Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future. Nils Bohr, Nobel Prize winner

Any business plan is a future-oriented document. Business plans are required to look between three and five years into the future. To produce them and accurately forecast sales, you will need estimates of expenses and other items, such as the required number of employees, interest rates, and general economic conditions. There are many different techniques and tools that can be used to forecast these items. The type of techniques used will be influenced by many factors, such as the following:

- The size of the business. Smaller businesses may have fewer resources to apply a wide variety of forecasting techniques.

- The analytical sophistication of people who will be conducting the forecast. The owner of a home business may have no prior experience with forecasting techniques.

- The type of the organization. A manufacturing concern that sells to a stable and relatively predictable environment that has been in existence for years might be able to employ a variety of standard statistical forecasting techniques; however, a small firm operating in a new or a chaotic environment might have to rely on significantly different techniques.

- Historical records. Does the firm have historical records for sales that can be used to project into the future?

There is no universal set of forecasting techniques that can be used for all types of small and midsize businesses. Forecasting can fall into a fairly comprehensive range of techniques with respect to level of sophistication. Some forecasting can be done on an intuitive basis (e.g., back-of-the-envelope calculations); others can be done with standard computer programs (e.g., Excel) or programs that are specifically dedicated to forecasting in a variety of environments.

A brief review of basic forecasting techniques shows that they can be divided into two broad classes: qualitative forecasting methods and quantitative forecasting methods. Actually, these terms can be somewhat misleading because qualitative forecasting methods do not imply that no numbers will be involved. The two techniques are separated by the following concept: qualitative forecasting methods assume that one either does not have historical data or that one cannot rely on past historical data. A start-up business has no past sales that can be used to project future sales. Likewise, if there is a significant change in the environment, one may feel uncomfortable using past data to project into the future. A restaurant operates in a small town that contains a large automobile factory. After the factory closes, the restaurant owner should anticipate that past sales will no longer be a useful guideline for projecting what sales might be in the next year or two because the owner has lost a number of customers who worked at the factory. Quantitative forecasting, on the other hand, consists of techniques and methods that assume you can use past data to make projections into the future.

“Overview of Forecasting Methods” provides examples of both qualitative forecasting methods and quantitative forecasting methods for sales forecasting. Each method is described, and their strengths and weaknesses are given.

Overview of Forecasting Methods

| Technique | Description | Strength | Weakness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Sales Forecasting Methods | |||

| Simple extrapolation | This approach uses some data and simply makes a projection based on these data. The data might indicate that a particular section of town has many people walk through the section each day. Knowing that number, a store might make a simple estimate of what sales might be. | An extremely simple technique that requires only the most basic analytical capabilities. | Its success depends on the “correctness” of the assumptions and the ability to carry them over to reality. You might have the correct number of people passing your store, but that does not mean that they will buy anything. |

| Sales force | In firms with dedicated sales forces, you would ask them to estimate what future sales might be. These values would be pieced together with a forecast for next year. | The sales force should have the pulse of your customers and a solid idea of their intentions to buy. Its greatest strength is in the B2B environment. | Difficult to use in some business-to-customer (B2C) environments. Sales force members are compensated when they meet their quotas, but this might be an incentive to “low-ball” their estimates. |

| Expert opinion | Similar to sales force approach, this technique ask experts within the company to produce estimates of future sales. These experts may come from marketing, R&D, or top-level management. | Coalescing sales forecasts of experts should lead to better forecasts. | Teams can produce biased estimates and can be influenced by particular members of the team (i.e., the CEO). |

| Delphi | A panel of outside experts would be asked to estimate sales for a particular product or service. The results would be summarized in a report and given to the same panel of experts. They would then be asked to read their forecast. This might go through several iterations. | Best used for entirely new product service categories. | One has to be able to identify and recruit “experts” from outside the organization. |

| Historical analogy | With this technique, one finds a similar product’s or service’s past sales (life cycle) and extrapolates to your product or service. A new start-up has developed an innovative home entertainment product, but nothing like it has been seen in the market. You might examine past sales of CD players to get a sense of what future sales of the new product might be like. | One can acquire a sense of what factors might affect future sales. It is relatively easy and quick to develop. | One can select the wrong past industry to compare, and the future may not unfold in a similar manner. |

| Market research | The use of questionnaires and surveys to evaluate customer attitudes toward a product or a service. | One gains very useful insights into the stated desires and interests of consumers. Can be highly accurate in the short term. | Experienced individuals should do these. They can take time to conduct and are relatively expensive. |

| Quantitative Sales Forecasting Methods | |||

| Trend analysis | This forecasting technique assumes that sales will follow some form of pattern. For example, sales are projected to increase at 15 percent a year for the next five years. | Extremely simple to calculate. | Sales seldom follow the same growth rate over any length of time. |

| Moving average | This technique takes recent class data for N number of periods, adds them together, and divides by the number N to produce a forecast. | Easy to calculate. | The basic use of this type of model fails to consider the existence of trends or seasonality in the data. |

| Seasonality analysis | Many products and services do not have uniform sales throughout the year. They exhibit seasonality. This technique attempts to identify the proportion of annual sales sold for any given time. The sales of swimming pool supplies in the Northeast, for example, would be much higher in the spring and summer than in the fall and winter. | Many products and services have seasonal demand patterns. By considering such patterns, forecasts can be improved. | Requires several years of past data and careful analysis. Useful for quarterly or monthly forecasts. |

| Exponential smoothing | This analytical technique attempts to correct forecasts by some proportion of the past forecast error. | Incorporates and weighs most recent data. Attempts to factor in recent fluctuations. | Several types of this model exist, and users must be familiar with their strengths and weaknesses. Requires extensive data, computer software, and a degree of expertise to use and interpret results. |

| Causal models—regression analysis | Causal models, of which there are many, attempt to identify why sales are increasing or decreasing. Regression is a specific statistical technique that relates the value of the dependent variable to one or more independent variables. The dependent variable sales might be affected by price and advertising expenditures, which are independent variables. | Can be used to forecast and examine the possible validity of relationships, such as the impact on sales by advertising or price. | Requires extensive data, computer software, and a high degree of expertise to use and interpret results. |

Forecasting key items such as sales is crucial in developing a good business plan. However, forecasting is a very challenging activity. The further out the forecast, the less likely it will be accurate. Everyone recognizes this fact. Therefore, it is useful to draw on a variety of forecasting techniques to develop your final forecast for the business plan. To do that, you should have a fairly solid understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the various approaches. There are many books, websites, and articles that could assist you in understanding these techniques and when they should or should not be used. In addition, one should be open to gathering additional information to assist in building a forecast. Some possible sources of such information would be associations, trade publications, and business groups. Regardless of what technique is used or the data source employed in building a forecast for business plan, one should be prepared to justify why you are employing these forecasting models.

Web Resources for Forecasting

- Three methods of sales forecasting (sbinfocanada.about.com/od/cashflowmgt/a/salesforecast.htm). This site provides three simplified approaches to sales forecasting.

- Time-critical decision making for business administration (home.ubalt.edu/ntsbarsh/stat-data/forecast.htm). This site has an e-book format with several chapters devoted to analytical forecasting techniques.

Building a Plan

Building your first business plan may seem extremely formidable. This may explain why there are so many software packages available to assist in this task. After building your first business plan, that steep learning curve should make subsequent plans for the business or other businesses significantly easier.

In preparing to build a business plan, there are some problem areas or mistakes that you should be on guard to avoid. Some may be technical in nature, while others relate to content issues. For the technical side, first and foremost, one should make sure that there are no misspellings or punctuation errors. The business plan should follow a logical structure. No ideal business plan clearly specifies the exact sections that need to be included nor is there an ideal length. Literature concerning business plans indicates that the appropriate length of the body of a business plan line should be between twenty and forty pages. This does not include appendixes that might provide critical data for the reader.

In developing a lengthy report, sometimes it is easy to fall into clichés or overused expressions. These should be avoided. Consider the visuals in the report. Data should be placed in either clearly mapped-out tables or well-designed graphs. The report should be as professional-looking as possible. Anticipate the audience that will be reading the report and write in a way that easily reaches them; avoid using too much jargon or technical terms.

The content in any business plan centers on two areas: realism and accuracy.

Components of the Plan

There is no idealized structure for a business plan or a definitive number of sections that it must contain. The following subsections discuss the outline of a plan for a business start-up and identify some of the major sections that should be part of the plan.

Cover Page

The cover page provides the reader with information about either the author of the plan or the person to contact concerning the business plan. It should contain all the pertinent information to enable the reader to contact the author, such as the name of the business, the business logo, and the contact person’s address, telephone number, and e-mail address.

The table of contents enables the reader to find the major sections and components of the plan. It should identify the key sections and subsections and on which pages those sections begin. This enables the reader to turn to sections that might be of particular importance.

Executive Summary

The executive summary is a section of critical importance and is perhaps the single most important section of the entire business plan. Quite often, it is the first section that a reader will turn to, and sometimes it may be the only section of the business plan that he or she will read. Chronologically, it should probably be the last section written.[24] The executive summary should provide an accurate overview of the entire document, which cannot be done until the whole document is prepared.

If the executive summary fails to adequately describe the idea behind the business or if it fails to do so in a captivating way, some readers may discard the entire business plan. As one author put it, the purpose of the executive summary is to convince the reader to “read on.”[25] The executive summary should contain the following pieces of information:

- What is the company’s business?

- Who are its intended customers?

- What will be its legal structure?

- What has been its history (where one exists)?

- What type of funding will be requested?

- What is the amount of that funding?

- What are the capabilities of the key executives?

All this must be done in an interesting and captivating way. The great challenge is that executive summaries should be relatively short—between one and three pages. For many businesspeople, this is the great challenge—being able to compress the required information in an engaging format that has significant size limitations.

Business Section

Goals. These are broad statements about what you would like to achieve some point in the near future. Your goals might focus on your human resource policies (“We wish to have productive, happy employees”), on what you see as the source of your competitive advantage (“We will be best in service”), or on financial outcomes (“We will produce above average return to our investors.”) Goals are useful, but they can mean anything to anyone. It is therefore necessary to translate the goals into objectives to bring about real meaning so that they can guide the organization. Ideally, objectives should be SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and have a specific timeline for completion. Here is an example: one organizational goal may be a significant rise in sales and profits. When translating that goal into an objective, you might word the objectives as follows: a 15 percent increase in sales for the next three years followed by a 10 percent increase in sales for the following two years and a 12.5 percent increase in profits in each of the next five years. These objectives are quite specific and measurable. It is up to the decision-maker to determine if they are achievable and realistic. These objectives—sales and profits—clearly specify the time horizon. In developing the plan, owners are often very happy to develop goals because they are open to interpretation, but they will avoid objectives. Goals are sufficiently ambiguous, whereas objectives tie you to particular values that you will have to hit in the future. People may be concerned that they will be weighed on a scale and found wanting for failing to achieved their objectives. However, it is critical that your plan contains both goals and objectives. Objectives allow investors and your employees to clearly see where the firm intends to go. They produce targeted values to aim for and, therefore, are critical for the control of the firm’s operations.

Vision and Mission Statements. To many, there is some degree of confusion concerning the difference between a vision statement and a mission statement. Vision statements articulate the long-term purpose and idealized notion of what a business wishes to become. In the earliest days of Microsoft, when it was a small business, its version of a vision statement was as follows: “A computer on every desk and in every home.” In the early 1980s, this was truly a revolutionary concept. Yet it gave Microsoft’s employees a clear idea (vision) that to bring that vision into being, the software being developed would have to be very “user-friendly” in comparison to the software of that day. Mission statements, which are much more common in small business plans, articulate the fundamental nature of the business. This means identifying the type of business, how it will leverage its competencies, and possibly the values that drive the business. Put simply, a mission statement should address the following questions:

- Who are we? What business are we in?

- Who do we see as our customers?

- How do we provide value for those customers?

Sometimes vision and mission statements are singularly written for external audiences, such as investors or shareholders. They are not written for the audience for whom it would have the greatest meaning—the management team and the employees of the business. Unfortunately, many recognize that both statements can become exercises of stringing together a series of essentially meaningless phrases into something that appears to sound right or professional. You can find software on the web to automatically generate such vacuous and meaningless statements.

Sometimes a firm will write a mission statement that provides customers, investors, and employees with a clear sense of purpose of that company. Zappos has the following as its mission statement: “Our goal is to position Zappos as an online service leader. If we can get customers to associate Zappos as the absolute best in service, then we can expand beyond shoes.”[26] The mission statement of Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream focuses both on defining their product and their values: “To make, distribute and sell the finest quality all-natural ice cream and euphoric concoctions with a continued commitment to incorporating wholesome, natural ingredients and promoting business practices that respect the Earth and the Environment.”[27]

Keys to Success. This section identifies those specific elements of your firm that you believe will ensure success. It is important for you to be able to define the competencies that you intend to leverage to ensure success. What makes your product or service unique? What specific set of capabilities do you bring to the competitive scene? These might include the makeup of and the experience of your management team; your operational capabilities (e.g., unique skills in design, manufacturing, or delivery); your marketing skill sets: your financial capabilities (e.g., the ability to control costs); or the personnel that make up the company.

Industry Review

In this section, you want to provide a fairly comprehensive overview of the industry. A thorough understanding of the industry that you will be operating in is essential to understand the possible returns that your company will earn within that industry. Investors want to know if they will recover their initial investment. When will they see a profit? Remember, investors often carefully track industries and are well aware of the strengths and limitations within a particular industry. Investors are looking for industries that can demonstrate growth. They also want to see if the industry is structurally attractive. This might entail conducting Porter’s five forces analysis; however, this is not required in all cases. If there appear to be some issues or problems with industry-level growth, then you might want to be able to identify some segments of the industry where growth is viable.

Products or Services

This section should be an in-depth discussion of what you are offering to customers. It should provide a complete and clear statement of the products or the services that you are offering. It should also discuss the core competencies of your business. You should highlight what is unique, such as a novel product or service concept or the possession of patents. You need to show how your product or service specifically meets particular market needs. You must identify how the product or the service will satisfy specific customers’ needs. If you are dealing with a new product or service, you need to demonstrate what previously unidentified needs it will meet and how it will do so. At its birth, Amazon had to demonstrate that an online bookstore would be preferable to the standard bookstore by offering the customer a much wider selection of books than would be available at an on-site location.

This section could include a discussion of technical issues. If the business is based on a technological innovation—such as a new type of software or an invention—then it is necessary to provide an adequate discussion of the specific nature of the technology. One should take care to always remember the audience for whom you are writing the plan. Do not make this portion too technical in nature. This section also might discuss the future direction of the product or service—namely, where will you be taking (changing) the product or the service after the end of the current planning horizon? This may require a discussion of future investment requirements or the required time to develop new products and services. This section may also include a discussion of pricing the product or the service, although a more detailed discussion of the issue of pricing might be found in the marketing plan section. If you plan to include the issue of pricing here, you should discuss how the pricing of the product or the service was determined. The more detailed you are in this description, the more realistic it will appear to the readers of the business plan. You may wish to discuss relationships that you have with vendors that might have an impact on reducing cost and therefore an impact on price. It is important to discuss how your pricing scheme will compare with competitors. Will it be higher than average or below the average price? How does the pricing fit in with the overall strategy of the firm?

This section must have a high degree of honesty. Investors will know much about the industry and its limitations. You need to identify any areas that might be possible sources of problems, such as government regulations, issues with new product development, securing distribution channels, and informing the market of your existence. Further, it is important to identify the current competitors in the industry and possible future competitors.

Marketing Plan

An introductory marketing course always introduces the four Ps: product, price, place, and promotion. The marketing section of the business plan might provide more in-depth coverage of how the product or the service better meets customer value than that of competitors. It should identify your target customers and include coverage of who your competitors are and what they provide. The comparison between your firm and its competitors should highlight differences and point to why you are providing superior value. Pricing issues, if not covered in the previous section, could be discussed or discussed in more detail.

The issue of location, particularly in retail, should be covered in detail. Perhaps one of the most important elements of the marketing plan section is to specify how you intend to attract customers, inform them of the benefits of using your product or service, and retain customers. Initially, customers are attracted through advertising. This section should delineate the advertising plan. What media will be used—flyers, newspapers, magazines, radio, television, web presence, direct marketing, and/or social media campaigns? This section should cover any promotional campaigns that might be used.

The Management Team

Physical resources are not the only determinant of business success. The human resources available to a firm will play a critical role in determining its success. Readers of your business plan and potential investors should have a clear sense of the management team that will be running a business. They should know the team with respect to the team’s knowledge of the business, their experience and capabilities, and their drive to succeed. Arthur Rock, a venture capitalist, was once quoted as saying, “I invest in people, not the idea.”[28]

This section of the business plan has several elements. It should contain an organizational chart that will delineate the responsibilities and the chain of command for the business. It should specify who will occupy each major position of the business. You might want to explain who is doing what job and why. For every member of the management team, you should have a complete résumé. This should include educational background (both formal and informal) and past work experience, including the jobs they have held, responsibilities, and accomplishments. You might want to include some other biographical data such as age, although that is not required.

If you plan to use specific advisers or consultants, you should mention the names and backgrounds of these people in this section of the plan. You should also specify why these people are being used.

An additional element of your discussion of the management team will be the intended compensation schemes. You should specify the intended salaries for the management team while also including issues of their benefits and bonuses or any stock position that they may take in the company. This section should also identify any gaps in the management team and how you intend to fill these positions.

Depending on the nature of the business, you might wish to include in this section the personnel (employees) that will be required. You should identify the number of people that are currently working for the firm or that will have to be hired; you should also identify the skills that they need to possess. Further discussion should include the pay that will be provided: whether they will be paid a flat salary or paid hourly, if and when you intend to use overtime, and what benefits you intend to provide. In addition, you should discuss any training requirements or training programs that you will have to implement.

Financial Statements

The financial statements section of the business plan should be broken down into three key subsections: the income statement, the balance sheet, and the cash-flow statement. Before proceeding with these sections, we discuss the assumptions used to build these sections. The opening section of the financial statements section should also include, in summary format, projections of sales, the sales growth rate, key expenses and their growth rates, net income across the forecasting horizon, and assets and liabilities.[29]

As previously discussed, bankers—and to lesser extent venture capitalists—will be primarily concerned with this section of the business plan. It is vital that this section—whether you are an existing business seeking more funding or a start-up—have realistic financial projections. The business plan should contain clear statements of the underlying assumptions that were used to make these financial projections. The clearer the statements and the more realistic the assumptions behind these statements, then the greater the confidence the reader will have in these projections. Few businesspeople have a thorough understanding of these financial statements; therefore, it is advisable that someone with an accounting or a financial background review these statements before they are included in the report. We will have a much more in-depth discussion of these statements in Chapter 9.

The future planning horizon for financial projections is normally between three and five years. The duration that you will use will depend on the amount of capital that the business is seeking to raise, the type of industry the business is in, and the forecasting issues associated with making projections. Also, the detail required in these financial statements will be directly tied to the type and size of the business.

Income Statement

The income statement examines the overall profitability of a firm over a particular period of time. As such, it is also known as a profit-and-loss statement. It identifies all sources of revenues generated and expenses incurred by the business. For the business plan, one should generate annual plans for the first three to five years. Some suggest that the planner develop more “granulated” income statements for the first two years. By granulated, we mean that the first year income statement should be broken down on a monthly basis, while the second year should be broken down on a quarterly basis.

Some of the key terms (they will be reviewed in much greater detail in Chapter 10) found in the income statement are as follows:

- Income. All revenues and additional incomes produced by the business during the designated period.

- Cost of goods sold. Costs associated with producing products, such as raw materials and costs associated directly with production.

- Gross profit margin. Income minus the cost of goods sold.

- Operating expenses. Costs in doing business, such as expenses associated with selling the product or the service, plus general administration expenses.

- Depreciation. This is a special form of expense that may be included in operating expenses. Long-term assets—those whose useful life is longer than one year—decline in value over time. Depreciation takes this fact into consideration. There are several ways in which this declining value can be determined. It is a noncash expenditure expense.

- Total expenses. The cost of goods sold plus operating expenses and depreciation.

- Net profit before interest and taxes. This is the gross profit minus operating expenses; another way of stating net profit is income minus total expenses.

- Interest. The required payment on all debt for the period.

- Taxes. Federal, state, and local tax payments for the firm.

- Net profit. This is the net profit after interest and taxes. This is the term that many will look at to determine the potential success of business operations.

Balance Sheet

The balance sheet examines the assets and liabilities and owner’s equity of the business at some particular point in time. It is divided into two sections—the credit component (the assets of the business) and the debit component (liabilities and equity). These two components must equal each other. The business plan should have annual balance sheet for the three- or five-year planning horizon. The elements of the credit component are as follows:

- Current assets. These are the assets that will be held for less than one year, including cash, marketable securities, accounts receivable, notes receivable, inventory, and prepaid expenses.

- Fixed assets. These assets are not going to be turned into cash within the next year; these include plants, equipment, and land. It may also include intangible assets, such as patents, franchises, copyrights, and goodwill.

- Total assets. This is the sum of current assets and fixed assets.

Liabilities consist of the following:

- Current liabilities. These are debts that are to be paid within the year, such as lines of credit, accounts payable, other items payable (including taxes, wages, and rents), short-term loans, dividends payable, and current portion of long-term debt.

- Long-term liabilities. These are debts payable over a period greater than one year, such as notes payable, long-term debt, pension fund liability, and long-term lease obligations.

- Total liabilities. This is the sum of current liabilities and long-term liabilities.

- Owner’s equity. This represents the value of the shareholders’ ownership in the business. It is sometimes referred to as net worth. It may be composed of items such as preferred stock, common stock, and retained earnings.

Cash-Flow Statement

From a practical and survival standpoint, the cash-flow statement may be the most important component of the financial statements. The cash-flow statement maps out where cash is flowing into the firm and where it flows out. It recognizes that there may be a significant difference between profits and cash flow. It will indicate if a business can generate enough cash to continue operations, whether it has sufficient cash for new investments, and whether it can pay its obligations. Businesspeople soon realize that profits are nice, but cash is king.

Cash flows can be divided into three areas of analysis: cash flow from operations, cash flow from investing, and cash flow from financing. Cash flow from operations examines the cash inflows from revenues and interest and dividends from investments held by the business. It then identifies the cash outflows for paying suppliers, employees, taxes, and other expenses. Cash flow from investing examines the impact of selling or acquiring current and fixed assets. Cash flow from financing examines the impact on the cash position from the changes in the number of shares and changes in the short- and long-term debt position of the firm. Given the critical importance of cash flow to the survival of the small business, it will be covered in much more detail in Chapter 10.

Additional Information

Depending on the nature of the business and the amount of funding that is being sought, the plan might include more materials. For an existing business, you may wish to include past tax statements and/or personal financial statements. If the business is a franchise, you should include all legal contracts and documents. The same should be done for any leasing, licensing, or rent agreements. This section should be seen as a catchall incorporating any materials that would support the plan. One does not want to be in the position of being asked by readers of the plan—“Where are these documents?”

Appendixes

The financial section of the business plan should include summaries of the three key financial elements. The details behind the financial statements should be included as an appendix along with clear statements concerning the assumptions that were used to build them. The appendixes may also include different scenarios that were considered in building the plan, such as alternative market growth assumptions or alternative competitive environments. Demonstrating that the author(s) considered “what-if” situations tells potential investors that the business is prepared to handle changing conditions. It should include items such as logos, diagrams, ads, and organizational charts.

Developing Scenarios

Change is constant. – Benjamin Disraeli

Business plans are analyses of the future; they can err on the side of either optimistic projections or conservative projections. From the standpoint of the potential investor, it is always better to err on the side of conservatism. Regardless of either bias, business plans are generally built on the basis of expected futures and past experience. Unfortunately, the future does not always emerge in a clearly predicated manner. One can have a dramatic change that can have significant impact on the business. Often such changes occur in the external environment and are beyond the control of the business management team. These external changes can occur within the technical environment; it can be based on changes in customer needs, changes with respect to the suppliers, changes in the economic environment—at the local, national, or global level. Dramatic change can also occur within the organization itself—the death of the owner or members of the management team.[30]