11 Chapter 11 – Supply Chain Management

The Supply Chain and a Firm’s Role in It

No man is an island, entire of itself. – John Donne[1]

Given the almost daily exposure and coverage of modern business theories or concepts in the popular press, one of the great challenges for both small business owners and corporate executives is the need to separate the wheat from the chaff. In the last four or five decades, businesspeople have heard and read about the next great idea that will revolutionize business as we know it. One almost feels obligated to run out and buy a book that lays out the general principles of concepts such as management by objectives, business process reengineering, transactional versus transformational leadership, management by walking around, the learning organization, matrix management, benchmarking, lean methodologies, and several quality systems—total quality management, the Deming method, and Six Sigma. Some of these have proven to be business fads and have run their course—sometimes with poisonous effects.[2] Others, such as lean methodologies and some quality systems, have proven to be solid bases on which to improve an organization’s efficiency and effectiveness.

A modern concept that has been popularized over the last two decades is that of supply chain management. In one sense, supply chain management is as old as business itself. One has to look only at the traffic along antiquity’s Silk Road trade route. This route was used to move goods across Asia’s vast steppes between China and the Middle East and as far west as ancient Rome. It possessed most of the fundamental elements of today’s supply chain: goods were produced (make), transported (move), deposited in warehouses (store), purchased by merchants (buy), and sold to customers. As will be seen, these five activities are the core of any supply chain.[3] If these activities have been universal dimensions of business, then what is different about supply chain management? That question will now be addressed.

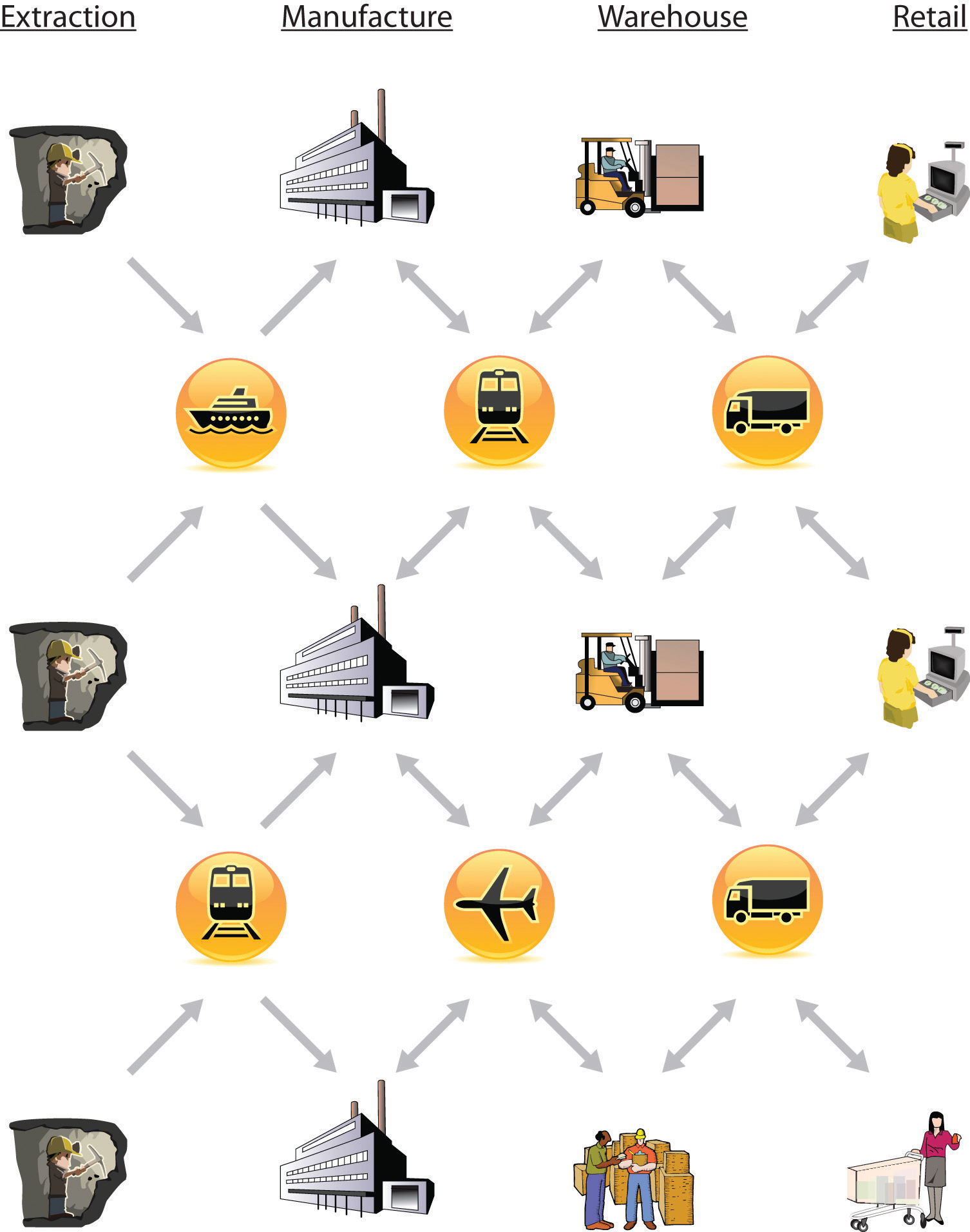

Material Flows in a Supply Chain

What Is a Supply Chain?

The owners of many small businesses may pride themselves on knowing many—if not all—of their employees. Other small businesses may have some degree of familiarity with most of their customers. They may have professional contacts with someone at the office of their immediate suppliers. Beyond those contacts, the daily demands of operations may mean that they have failed to see their firm’s position in the larger context known as the supply chain. What precisely do we mean when we use the term supply chain management? Industrial organizations and academics provide several different definitions of supply chain management.

The Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals provides the following definition: “Supply chain management encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement, conversion, and all logistics management activities. Importantly, it also includes coordination and collaboration with channel partners, which can be suppliers, intermediaries, third party service providers, and customers. In essence, supply chain management integrates supply and demand management within and across companies.”[4]

The Association for Operations Management (APICS) defines a supply chain as “a total systems approach to designing and managing the entire flow of information, materials, and services—from raw material suppliers, through factories and warehouses, and finally to the customer…The chain comprises many links, such as links between suppliers that provide inputs, links to manufacturing and service support operations that transform the input into products and services, and links to the distribution and local service providers that localized the product.”[5]

In a seminal article on the subject, supply chain management was defined as follows: “Supply chain management is the systemic, strategic coordination of the traditional business functions and the tactics across these business functions within a particular company and across businesses within the supply chain, for the purposes of improving the long-term performance of the individual companies and the supply chain as a whole.”[6]

For our purpose, we define the supply chain as follows: “It is a systematic and integrated flow of materials, information, and money from the initial raw material supplier through fabricators, manufacturers, warehouses, distribution centers, retailers, and the final customer. Its ultimate objective is the improvement of the entire process, which means an increase of economic performance of all participants and an increase in value for the end customer.”

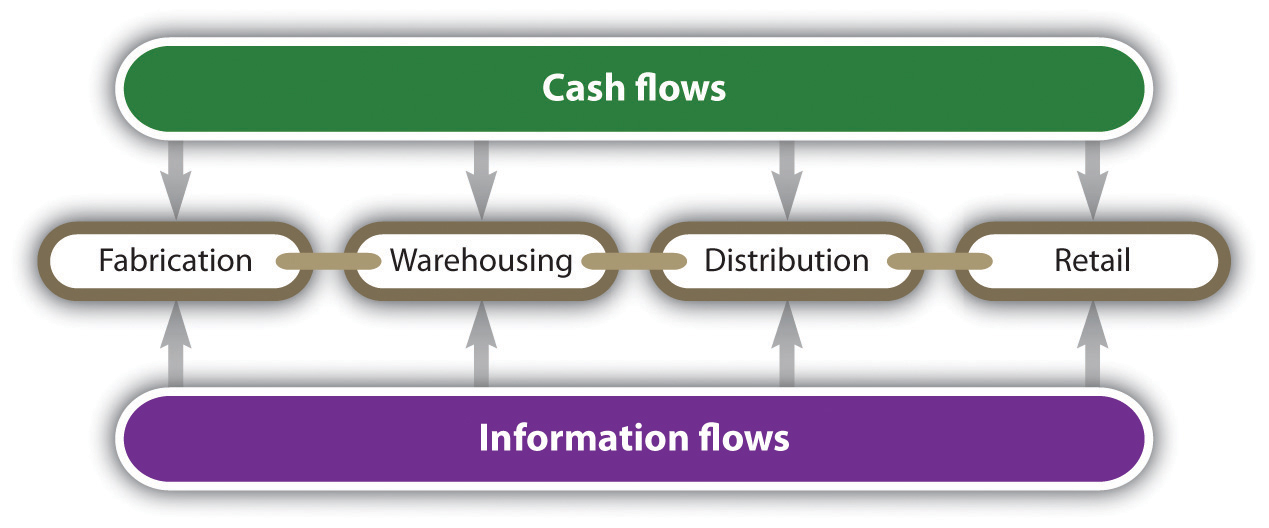

If we examine these definitions, several common themes stand out. Supply chain management is not limited to the flow of goods and materials. The successful supply chain requires a consideration of both financial flows and information flows across the entire chain. A second theme is that organizations must overcome myopia of just being concerned with their immediate suppliers and customers. They must take into consideration their suppliers’ suppliers and their customers’ customers. To be able to do this, organizations must expand the flow of communication and information.

Additional Flows in a Supply Chain

One might easily pose the following question: How has the concept of supply chain management taken off in the last twenty years? The proliferation of supply chain management is a core concept for businesses that can be attributed to several major factors, including the following:

- The increasing importance of globalization. Global trade has seen a spectacular increase in the last half century. It is estimated that international trade has increased by 100 percent increase since 1955.[7] The end of the Cold War in the early 1990s produced a political environment conducive to the promotion of the notion of free trade. Free trade advocates that nations lower or eliminate trade barriers and tariffs so that countries might develop some particular competencies so that they can participate in the global economy. Several trading blocs have been built during the last three decades that facilitate trade among their partners, including the European Union, which currently consists of twenty-seven countries with a total population in excess of five hundred million and a gross domestic product (GDP) greater than that of the United States. The European Union shares a common currency, and there are no trade barriers among its member states. NAFTA stands for the North American Free Trade Agreement and encompasses Canada, the United States, and Mexico. With respect to the combined GDP of these three countries, NAFTA represents the largest trading bloc in the world. Two other trading blocs in the Western Hemisphere are the Dominican Republic-Central American Free Trade Agreement and MERCOSUR (Common Southern Agreement), which promotes trade among Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The spectacular growth of international finance should also be considered when examining the growth of globalism in recent history.

- Changes in consumer demands. Across the world, consumers are becoming progressively more demanding. They expect better quality products with more options and at a lower cost. One has to look only at the global market for cell phones for an example. Even in countries that might be classified as Third World countries, consumers expect to be able to buy cell phones with cutting-edge capability at reasonable prices. This results in a great need for new products, which in turn requires a reduction in life cycle development times. Normally, increasing the product development time would generally result in higher cost, something that is unacceptable today. To meet increasing and often conflicting demands, businesses find that they must work closely with members of their supply chain.

-

Organizations that have recognized the need to change. Increasingly, more and more businesses recognize that old models may no longer function. In the past, many businesses strove to be vertically integrated. This meant that they wanted to control as many aspects of their operations as possible. Large oil companies exhibit vertical, industry-wide integration. A firm such as Exxon-Mobil has the capacity to carry out almost all the functions associated with the petroleum industry. Exxon-Mobil has units that can explore for oil, drill for oil, transport oil, refine oil into gasoline, and sell it directly to consumers. In this way, it has almost complete control over the entire supply chain. This approach—total vertical integration—may work in some industries where firms recognize that it is economically advantageous to outsource noncore activities. Firms are making the decision whether to make or buy, and they are finding it financially attractive to have other businesses make components or products for them. As outsourcing became more popular, there was immediate recognition that businesses had to pay careful attention to all the elements of their supply chains. They had to develop working relationships with their suppliers and their customers. Successful supply chain management requires new approaches for dealing with suppliers. Those businesses that have successfully made this transition can fully exploit the benefits of supply chain management.

Another area where businesses have learned to change, which has greatly impacted the acceptance of supply chain management, is the change from a push philosophy to a pull philosophy. A push philosophy means that a business produces goods and services and pushes it into the marketplace. A push-based system will forecast demand in the market, produce the required amount, push the product out the door, and hope that the forecast was correct. In contrast, a pull philosophy means that the production of goods and services is initiated only when the marketplace or the consumer demands it. Production is initiated by actual demand.

- Technical innovations. Today’s approach to supply chain management would be impossible without technological revolutions in the fields of communication and computer software. It would be impossible to operate in a global supply chain without the Internet.

Key Elements of a Supply Chain

What precisely makes up a supply chain management system? Various authors identify the different components or elements of such a system.[8] The simple list would include four core elements: procurement, operations, distribution, and integration.

The Core Elements of a Supply Chain Management System

The first of the four elements—procurement—begins with the purchasing of parts, components, or services. However, it does not end with the purchase. Procurement must ensure that the right items are delivered in the exact quantities at the correct location on the specified time schedule at minimal cost. This means that procurement must concern itself with the determination of who should supply the parts, the components, or the services. It must address the question of assurance that these suppliers will deliver as promised. The opening phrase of this question is often as follows: should the business make or buy a particular part or service? The make-or-buy question can have both strategic significance and economic significance. Some businesses will choose not to have others make or provide services because they believe they may lose control over particular technologies or skill sets. Will it benefit a business to have lower cost in the short run yet lose its source of competitive advantage in the long run to another competitor? Overseas outsourcing may pose difficulties with respect to communication difficulties, extended transportation distances, and timelines. The inability to ensure the overall quality of the outsourced item may be a deciding factor in not having another business make the part or provide the service. Recent difficulties with the quality assurance of products made in China have given many American manufacturers second thoughts about outsourcing.

There are, however, reasons for businesses to outsource production or services. The most obvious reason is associated with lower costs. Read the business press and discover the phrase the China price. This refers to the low cost of products produced in China given its low wages. One should not think that outsourcing is associated only with overseas manufacturing. Many firms will domestically outsource certain in-house service activities. The firm ADP specializes in preparing businesses payrolls, employee benefits, and tax compliance. ADP has been successful because it is able to provide a high-quality product at lower cost than many firms could produce in-house. Another reason why a business may outsource production or other activities is that the business is currently unable to meet particular demand levels.

If one were to exclude strategic considerations and merely look at economic issues, many make-or-buy decisions could be fairly straightforward variations of breakeven analysis. Imagine a firm is thinking about outsourcing the manufacture of a particular part to a Chinese firm. The plot is not unique from a technical standpoint, so outsourcing would have no strategic significance.

Data for Domestic Production versus Chinese Outsourcing Option

| Costs | Domestic Production ($) | Outsourcing to China ($) |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed costs | 40,000 | 4,000 |

| Labor cost per unit | 9.90 | 4.25 |

| Material cost per unit | 7.20 | 7.20 |

| Transportation cost per unit | 0.40 | 3.80 |

| Tariff duty per unit | 0.00 | 1.50 |

| Total cost per unit | 17.50 | 16.75 |

With these figures, there is no need to conduct a breakeven analysis. Outsourcing to China produces a lower total unit cost, and the fixed costs are significantly lower. The total cost reduction would dictate that China is the preferred location to produce the part. But now envision another scenario, one in which the transportation cost increases by $2.55 (increasing the transportation cost per unit to $6.35) and the tariff duty per unit increases by $1 per unit.

Revised Data for Domestic Production versus Chinese Outsourcing Option

| Costs | Domestic Production ($) | Outsourcing to China ($) |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed costs | 40,000 | 4,000 |

| Labor cost per unit | 9.90 | 4.25 |

| Material cost per unit | 7.20 | 7.20 |

| Transportation cost per unit | 0.40 | 6.35 |

| Tariff duty per unit | 0.00 | 2.50 |

| Total cost per unit | 17.50 | 19.30 |

Given these changes, we can now conduct a breakeven analysis.

| Domestic Production Total Costs | Outsourced to China Total Costs | |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed costs + total variable costs | = | Fixed costs + total variable costs |

| $40,000 + $17.50 * Q | = | $4,000 + $19.30 * Q |

| ($40,000 − $4,000) | = | ($19.30 − $17.50) * Q |

| $36,000 | = | $1.80 * Q |

| break-even point Q | = | 20,000 units |

| Q = Quantity | ||

This simply means that if the demand for the part is fewer than 20,000 units, then it is cheaper to produce the part in China; however, if the demand is greater than 20,000 units, it is cheaper to produce the part domestically.

The key issue in procurement is how one goes about selecting and maintaining a supplier, which can be approached from two directions. The first centers on how a firm might evaluate a potential supplier. The second is how a firm evaluates those businesses that are already suppliers to an operation. When looking at the potential suppliers of a business, a firm may be aided by examining those suppliers with some form of certification. Perhaps the most globally recognized certification program is ISO 9000, a program designed to ensure that suppliers are certified and fully committed to quality production. A supplier that is ISO 9000 certified may mean that incoming goods need not be tested. In examining suppliers, one might also look at the number of employees of the potential supplier who have received certification in the area of supply chain management. The Association for Operations Management, formerly known as the American Production and Inventory Control Society (APICS), has a program to certify professionals in supply chain management. After selecting a supplier, one must have a program that continuously evaluates the capability of the supplier. Some of the capabilities that may be considered include on-time delivery, the accuracy of delivery (i.e., correct items in the correct quantities are shipped), the ability to handle fluctuations in demand, and the ability to hold inventory until needed by the customer. One needs a comprehensive set of metrics to perform such an analysis. In addition, one must think about developing a new type of relationship with suppliers, one that is not adversarial but develops a close working relationship bordering on being an alliance.

The second major element of supply chain management system is operations. Having received raw materials, parts, components, assemblies, or services from suppliers, the firm now must transform them and produce the products or the services that meet the needs of its consumers. It must conduct this transformation in an efficient and effective manner for the benefit of the supply chain management system. We will briefly overview those operational activities that most directly relate to supply chain management.

One element is demand management. This involves attempting to match demand with capacity. In a manufacturing environment, this may entail a better and more detailed production schedule. In a service environment, it may entail rescheduling customer appointments to better match service provider availability. A key element is improvements in inventory control, which may be done by using materials requirement planning software or instituting a just-in-time program. Just-in-time attempts to create an inventory system where the inventory arrives exactly when it is needed. Another way of achieving operational efficiency to improve the supply chain management system is by adopting lean methodologies. The essence of lean is attempting to eliminate all forms of waste from a production or service system.

The third element of the supply chain management system is distribution. Distribution involves several activities—transportation (logistics), warehousing, and Customer relationship management (CRM). The first and most obvious is logistics—the transportation of goods across the entire supply chain. The need to efficiently transport goods has led to a hierarchy of logistics providers. Some argue that it now consists of a four-party hierarchy. First-party logistics providers are those who wish to ship goods to a particular location. Second-party logistics providers are those businesses that provide the means of transportation, including shipping freight by air, rail, or truck. Second-party logistics providers may also offer warehousing services to temporarily store goods. Third-party logistics providers specialize in offering an array of services to simplify transportation. They offer services that synthesize a variety of services, including the shipping of goods, warehousing, inventory management, and packaging. They also may offer services associated with facilitating customs operation and the resolution of problems associated with international transportation. The range of services can be so extensive that the literature segments third-party logistics providers into four groups.[9] They range from those businesses that pick up and deliver goods to those businesses that essentially perform the entire logistics function for a customer. In the last fifteen years, a fourth level of logistics providers was added to this hierarchy. Although there is some argument as to what distinguishes sophisticated third-party logistics providers from fourth-party logistics providers, the essential distinction is that fourth-party logistics providers function as consultants for supply chain management logistics issues. They are non-asset-based integrators[10]—firms do not own shipping assets or warehouses; they simply provide consulting services.

The CRM component of the distribution element represents an attempt to automate interactions with customers and facilitate the development of sales prospects through software packages. Most small businesses will start using CRM as a means of contacting current customers and future prospective customers. They then move on to software that automates the entire sales process. The ultimate goal of CRM is the greater connection with customers, thus providing them with greater value.

The last element of supply chain management is the need for integration. At the beginning of this chapter, we mentioned that many small businesses are unfamiliar with their immediate customers and their immediate suppliers; however, they may be part of a much larger chain. It is critical that all participants in the service chain recognize the entirety of the service chain. A failure to overcome the myopia of just being concerned with the immediate customer and the immediate supplier can produce significant disruptions in the entire chain. These disruptions can significantly increase costs and destroy value.

The impact of the failure to adopt a system-wide perspective—that is, examining the totality of the chain—is most clearly seen in what is known as the “bullwhip” effect. This effect illustrates how a narrow perspective can produce unexpected consequences. Envision a classic supply chain composed of a retailer—who is supplied by a wholesaler—who in turn is supplied by a distributor with a product coming from the manufacturer. Each element of this chain must forecast its anticipated demand and determine the appropriate levels of inventory. Because no element of this chain wishes to “stock out”—having insufficient inventory to meet a customer’s demand—each element will carry what is known as safety stock. In many cases, the more certain the demand, the greater the need for such safety stock. If demand at the retail level increases, then it follows that demand will also increase at each level further up the supply chain. If demand decreases at the retail level, the demand will likewise decrease further up the chain. The rate at which demand and inventory levels fluctuate is dependent on the lead time at each level in the chain. The delay between an increase for the retail level and the corresponding increase or decrease at the manufacturing level will be a function of this lead time. The bullwhip effect recognizes that the amplitude of inventory swings increases as one travels up the supply chain because each element of the supply chain is a relatively narrow focus of just trying to meet the needs of their customers. If the forecast for “shared” demand across the entire chain could be made simultaneously or if the lead time could be significantly reduced, then this phenomenon would not be quite as dramatic or problematic. The bullwhip effect calls for integrating information across the entire supply chain.

An Enterprise resource planning (ERP) system can successfully integrate information across the entire supply chain. An ERP system is an integrated set of computer programs that brings information about a firm’s accounting, financial, sales, and operations into a common database.[11] One also needs a series of metrics that would indicate the overall performance of the supply chain. This should also be part of the integration process.

Key Takeaways

- The supply chain involves the integration of goods, finances, and information from the initial supplier to the final customer.

- A revolution in supply chain management has been produced by globalization, changes in consumer demand, organizations that recognize the need for changing ways of doing business, and technical innovations.

- Supply chains are composed of four major elements: procurement, operations, distribution, and integration.

- Supply chain management should not be seen as appropriate only for large businesses.

A Firm’s Role in the Supply Chain

Developing New Relationships

Game theory is a branch of mathematics. Broadly stated, game theory examines competitive situations in which one’s outcomes may be influenced or dictated by the decisions of other players. It has been applied to a variety of worldwide domains, including economics, military operations, political science, and business strategy. It has its own very large literature base, and work in this field has been recognized by several Nobel prizes in economics. To better understand some of the risk associated for small businesses participating in supply chain management, we will briefly look at two types of games: zero-sum games and non-zero-sum games.

Zero-sum games are those in which the total benefits for all participants total zero. Baseball can be seen as a zero-sum game. If one is told that the New York Yankees and the New York Mets played an exhibition game and the Yankees won, then one also knows that the New York Mets lost. Basketball and most games in professional football are also zero-sum games because there is a winner and a loser. Poker can also be seen as a zero-sum game. If your five friends have a Friday night game of poker and one player is up $100, then you also know that the other four players have suffered a cumulative loss of $100.

Non-zero-sum games, on the other hand, are those that potentially have net results other than zero. This simply means that the loss of one player does not directly correspond to the game of another player. In a non-zero-sum game, it is possible for all the players to win or for all the players to lose. The classic illustration of a non-zero-sum game is known as the prisoner’s dilemma. The prisoner’s dilemma hypothesizes that two criminals (prisoner A and prisoner B) are arrested and charged with the same crime. At the police station, they are separated, and each is given the following option: if you inform on the other prisoner, you will be set free, while the other prisoner will receive a five-year sentence. Both prisoners would instinctively recognize that if they both remained silent, the police would have insufficient evidence to convict both of the crime. At worst, they would be held in the jail for several months. If, however, both prisoners informed on each other, they would probably receive a two-year sentence. Assuming that both prisoners wish to serve the minimal amount of time, their individual decisions will be dictated by what they believe will be the other prisoner’s decision. There are four possible outcomes to this scenario:

- Prisoner A informs on prisoner B while prisoner B remains silent. This is a win for prisoner A and a loss for prisoner B. This is a win-lose outcome.

- Prisoner B informs on prisoner A while prisoner A remains silent. This is a win for prisoner B and a loss for prisoner A. This is a win-lose outcome.

- Both prisoner A and prisoner B inform on each other. This situation essentially represents a loss for both prisoner A and prisoner B. This is a lose-lose outcome.

- Both prisoner A and prisoner B trust each other and remain silent. This results in both prisoners doing a minimal amount of time. In effect, this is a win-win for both individuals.

The point of this brief introduction to game theory is to highlight the possibility of creating a win-win scenario. In the prisoner’s dilemma, the key to achieving a win-win outcome is that both parties must have complete trust in each other. This concept of mutual trust plays a critical role in successful supply chain management. Far too often, both the supplier and the customer perceive the relationship as a win-lose outcome only. Customers want suppliers to provide items at the lowest possible cost, with the highest quality, delivered exactly when needed. Customers often use multiple suppliers and play them off against each other to guarantee the lowest possible price. Suppliers want to provide customers with items of the highest possible price, with acceptable quality, and delivered when it is convenient for the supplier. These attitudes produce a “dance” between the customer and the supplier, where both are trying to win even if that means that the other loses. These attitudes often stem from the fact that there is no trust between the customer and the supplier.

W. Edwards Deming, the famous management guru who was most commonly associated with the quality movement, had several interesting insights into areas that would be associated with supply chain management. As one of the few management theorists whose ideas were comprehensive enough to be synthesized into a coherent business philosophy, Deming summarized his approach to management in fourteen points. One of these points is as follows: “End the practice of awarding business on the basis of price. Instead, minimize total cost. Move toward a single supplier for any one item, with a long-term relationship of loyalty and trust.”[12]

Deming argued that the move toward a single supplier for a particular part could yield significant advantages. Using a single supplier requires that a customer must sign a multiyear agreement with the supplier. This enables both the supplier and the customer to better understand each other’s needs and capabilities. As this knowledge grows, the supplier can better serve the customer by improving quality, design, and service.[13] From these improvements, one can easily anticipate that there will be lower costs and higher profits. A multiyear contract with a supplier guaranteeing particular sales is invaluable to many suppliers because of the benefit of such a contract when that supplier must deal with its bank. Deming counters the argument for the need for multiple suppliers, in case a catastrophe or a disaster strikes that single supplier, by suggesting that a tight and trusting relationship will lead the supplier to develop sufficient contingency plans. Deming argues that a sense of joint responsibility comparable to a marriage comes from such trust.

Building such trust between two organizations is not easy. It will often require significant changes in one or both parties. Such change is best induced when it is clear to all participants that there is top-level management support for the new ways of doing business. Top management must articulate the shared vision between the two organizations. Top management must clearly identify the objectives and metrics to be used by both the supplier and the customer. People need to clearly understand the joint benefits from adopting the new way of business. In addition, even with electronic communication, it is highly advisable that members of both organizations meet on a regular basis and perhaps tour each other’s facilities.

The new relationships that are required for the success of any supply chain management program are not easy to implement, but they are vital. Every effort must be made to adopt this win-win perspective.

Managing Information in New Ways

Cost, profits, and financial ratios can provide useful insights into the overall efficiency and effectiveness of any business. However, they do not always tell the full story. A sudden spike in the price of oil, a flood that destroys a low-cost supplier, an increase in interest rates, the closing of a large plant in a small town, or a national banking crisis are all external factors that can cripple the financial viability of any business. These external factors lie beyond the control of even the best management team. Sometimes we need to be very careful about what we measure and how we should measure. Although it adds a layer of complexity to a basic accounting system, measurements that are useful for evaluating processes that serve customers can be provided.

When evaluating the supply chain of a business, there is a great need to carefully consider what metrics should be employed. Such a consideration should include at least some of the following factors:

- Total supply chain cost. All the operational expenditures of a cost associated with the requisite information systems.

- Cash-to-cash cycle time. The time between when an organization purchases raw materials and when they are paid by the customer.

- Delivery. The percentage of orders delivered on or before customer due dates.

- Flexibility. The amount of time required to handle a significant ramp up in production.[14]

For those who are seriously committed to maximizing the benefits from successful supply chain management, study the supply chain operations reference (SCOR) model. This model enables businesses to benchmark their supply chain management systems. Developed in 1996 by the Supply Chain Council in conjunction with AMR Research and Pittiglio Rabin Todd and Rath,[15] the purpose of the SCOR model is to provide methods to measure and benchmark the performance of the supply chain management system of a business. Currently, one thousand firms, universities, and government agencies participate in the continuing evolution of the SCOR model. It is predicated on three major components: process modeling, performance measurement, and the determination of best practices.

The process-modeling component begins with five essential elements that link together the supply chain: plan, source, make, deliver, and return. Plan refers to those processes associated with the design of the supply chain, planning activities associated with the other four processes, and the implementation of all these plans. These plans should enable management to identify any significant gaps and determine how these gaps will be closed. Source refers to the ordering and the acquisition of goods and services to meet anticipated demand, including purchase orders, scheduling, receipts, and storage. Make refers to those processes used to create the product or the service, including, for example, make to stock, make to order, or engineer to order. Deliver refers to those processes associated with the development and the fulfillment of customer orders, including scheduling, packaging, and shipping all orders. Lastly, return refers to those processes associated with the return of finished products by a customer. The SCOR model attempts to be as inclusive as possible with respect to these five major processes. Each process can be broken down into subcomponents. Currently, there are thirty subcomponents for the plan element, twenty-seven subcomponents for the source element, thirty-one subcomponents for the make element, sixty-one subcomponents for the deliver element, and thirty-six subcomponents for the return element. This program then goes on to identify specific metrics for nearly every subcomponent. It is the most comprehensive system of evaluation for supply chain management.

Key Takeaways

- In game theory’s non-zero-sum model, it is possible to produce win-win scenarios for multiple players.

- Win-win scenarios require mutual trust.

- Supply chain management success needs new levels of trust and respect for it to function properly in the long run.

- Supply chain management needs metrics to evaluate its performance.

- Existing models of supply chain metrics (SCOR) can handle the most complicated of supply chains.

The Benefits and the Risks of Participating in a Supply Chain

The Benefits of Successful Supply Chain Management

For any small business, a commitment to developing a supply chain management system is not a small undertaking. It involves the commitment of significant financial resources for the acquisition of appropriate software. Policies and procedures must be changed in accordance with the needs of the new system. Personnel must be trained in not only using the new software but also adapting to new ways of doing business. Small businesses accept these challenges of adopting supply chain management systems because such systems are viewed as being important for long-term survival and because businesses anticipate substantial management and economic benefits.

The management benefits of supply chain management system include the following:

- Silo busting. By their very nature, supply chain management systems improve communication across all functions within a business. This leads to employees having a better understanding of the entire operations of a business and how their work relates to the overall benefits of the business.

- Improve communications with suppliers and customers. Improved communications with customers enhances the overall value provided to those customers. The improvement in customer satisfaction leads to longtime relationships, which yields significant economic benefits. Improved communications with suppliers improve the overall operational efficiency of both participants, reduce costs, and improve profits.

- Supplier selection. Supply chain management systems can help businesses evaluate prospective suppliers and monitor the performance of current suppliers. This capability can lead to strategic sourcing and significant cost savings plus improvement of the when- and where-needed variables.

- Improvements in purchasing. The automation of purchasing reduces errors and improves the economic efficiency of the purchasing function. Disciplined purchasing can allow for the full exploitation of available discounts.

- Reduction of inventory costs. Supply chain management systems can produce significant cost savings across all levels of inventory. Improved forecasting and scheduling will lead to increases in inventory turns and a corresponding reduction of costs.

- Improvements in operations. Improved quality control reduces the scrap rate, which in turn can have significant cost savings. Better production scheduling translates into producing what is needed when it is needed. The business does not have to spend additional money trying to expedite the production of particular orders to customers. The cost of goods sold is reduced in this manner. An additional benefit of supply chain management systems is that they lead to better utilization of plant and equipment. Great utilization translates into less likelihood that unneeded assets will be acquired, which has major financial benefits.

- Error reduction. By automating processes, billing errors and errors associated with purchasing and shipping quantities can be reduced. This not only saves money but also improves satisfaction with both suppliers and customers.

- Improvements in transportation operations. Accurate deliveries reduce returns and their associated costs. Sophisticated shipping models can reduce the overall cost of transportation.

- Additional financial benefits. Such systems can improve the collections process, which impacts customer relations, reduces bad debts, and improves cash flow.

The Risks Associated with Supply Chain Management

The major risks associated with a supply chain management system fall into two categories: technical and managerial.

Michael Porter’s five forces model is a model of the major factors that contribute to an industry’s overall structure. It also points to factors that might affect the overall profitability of the particular business within that industry. The greater the strength of these forces, the greater the challenge to make above average return profits for businesses in that industry. It is useful to review two of those forces—the power of suppliers and the power of buyers—and reexamine how they might influence the profitability of any business in the supply chain.

Porter identifies the following factors that might contribute to the overall strength of each force. He argued that suppliers are powerful when the following occurs:

- They are concentrated. When an industry is dominated by only a few suppliers, these suppliers generally have a greater ability to dictate terms to their customers. The mining company DeBeers, which controls more than 50 percent of the world diamond production, is able to set the selling price of diamonds for most of the world’s jewelers.[16] It should be pointed out, however, that in some cases concentration, particularly a duopoly, provides an opportunity for customers to force the two competing firms to compete more readily against each other. Think of the situation of Boeing and Airbus and their relationship to their customers—various airlines. At present, there are only two major producers of commercial aircraft, and airlines sometimes obtain better deals from one manufacturer because of their desire to maintain parity in market share.

- The size of the suppliers is large relative to the buyers. Suppliers are powerful when they are large and sell to a set of fragmented buyers. Think of the largest oil companies that sell gasoline to independent stations. The power in this scenario lies with the large oil companies.

- Switching costs are high. Suppliers have power when the cost of switching to an alternative supplier is expensive. Many businesses stay with Microsoft products because to do otherwise means that they would have to repurchase new hardware and software for the entire organization.

Problems may also arise from a heavier reliance on one customer in the supply chain. Even large companies need to be aware of their relative strength in the supply chain. Rubbermaid is the most admired corporation in America, as voted by Fortune magazine in 1993 and 1994, yet it had significant difficulties when dealing with one of its major customers—Walmart. In the early 1990s, Rubbermaid found that the cost for a key ingredient—resin—had increased by 80 percent.[17] Walmart’s almost total focus on lowering its prices led it to drop many of Rubbermaid’s products. This began a downward spiral for Rubbermaid, which led to its acquisition by Newell Inc. Rubbermaid went from the status of the most admired corporation to being a basket case because it failed to recognize its excessive dependence on one customer.

Key Takeaways

- There are significant benefits for businesses that adopt supply chain management systems.

- The benefits stem from improved customer relations, cost cutting, and increased operational efficiencies.

- The adoption of a supply chain management perspective can pose risks.

- Businesses must consider the relative power of both their suppliers and their customers.

- John Donne, “XVII. Meditation,” The Literature Network, accessed February 4, 2012, www.online-literature.com/donne/409. ↵

- John Mickletwait and Adrian Woodridge, Witch Doctors: Making Sense of the Management Gurus (New York: Time Books, 1996), 22. ↵

- Scott Webster, Principles and Tools for Supply Chain Management (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2008), 62. ↵

- “CSCMP Supply Chain Management Definitions,” Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals, accessed February 1, 2012, cscmp.org/aboutcscmp/definitions.asp. ↵

- APICS—Operations Management Body of Knowledge Framework, 2nd ed. (Chicago: APICS, 2009). ↵

- John Mentzer, William DeWitt, James Keebler, Soonhong Min, Nancy Nix, Carlo Smith, and Zach Zacharia, “Defining Supply Chain Management,” Journal of Business Logistics 22, no. 2 (2001): 7. ↵

- Steve Schifferes, “Globalisation Shakes the World,” BBC News, January 21, 2007, accessed February 1, 2012, news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/6279679.stm. ↵

- Martin Murray, “Introduction to Supply Chain Management,” About.com, accessed February 1, 2012, logistics.about.com/od/supplychainintroduction/a/into_scm.htm; Phillip Edwards, “Supply Chain for Small Businesses and Its Benefit,” Small and Medium Business Corner, April 22, 2011, accessed February 1, 2012, smb-corner.com/2011/04/supply-chain-management-small-business; Joel D. Wisner, G. Keong Leong, and Keah-Choon Tan, Principles of Supply Chain Management: A Balanced Approach (Mason, OH: South-Western, 2004), 13. ↵

- Susanne Hertz and Monica Alfredsson, “Strategic Development of Third-Party Logistics Providers,” Industrial Marketing Management 32, no. 2 (2003): 139. ↵

- “Fourth-Party Logistics,” Business Dictionary.com, accessed February 27, 2012, www.businessdictionary.com/definition/fourth-party-logistics-4PL.html. ↵

- Cecil C. Bozarth and Robert B. Handfield, Introduction to Operations and Supply Chain Management, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007), 519. ↵

- Ken Boyer and Rohit Verma, Operations and Supply Chain Management for the 21st Century (Mason, OH: South-Western, 2009), 38. ↵

- W. Edwards Deming, The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), 232. ↵

- Joel D. Wisner, G. Keong Leong, and Keah-Choon Tan, Principles of Supply Chain Management: A Balanced Approach (Mason, OH: South-Western, 2004), 442. ↵

- Scott Webster, Principles and Tools for Supply Chain Management (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2008), 55. ↵

- Mason A. Carpenter and William G. Sanders, Strategic Management and Dynamic Perspective (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2008), 108. ↵

- Mary Ethridge, “News about the Wal-Mart Struggle,” accessed February 2, 2012, www.dsausa.org/lowwage/walmart/Dec17_03.html. ↵

A program in which the supervisor and the subordinate sit down and map out the objectives for the subordinate to accomplish in the upcoming year.

A management program that analyzes the processes of a business and tries to redesign them so that all non-value-added activities are eliminated.

An organization that is able to adapt to changing situations and pressures. It places a premium on organizations and individuals that can learn from the environment.

A program where a business looks at the world leaders in particular processes and attempts to emulate them.

A systematic and integrated flow of materials, information, and money from the initial raw material supplier through fabricators, manufacturers, warehouses, distribution centers, retailers, and the final customer.

A process that not only involves the purchasing of parts, components, or services but also considers that the right parts are delivered in the exact quantities at the correct location on the specified time schedule at minimal cost.

The activities and tasks associated with turning a firm’s inputs (materials, capital, and labor) into goods and services.

A computerized inventory control system that schedules the production of goods and takes into consideration the available and the required inventory.

An approach to inventory that seeks to eliminate excess waste and reduce inventory to a minimal level.

A series of techniques designed to eliminate waste from manufacturing and service processes and provide greater customer value.

A process that involves several activities: transportation (logistics), warehousing, and CRM.

The active management of the distribution of materials throughout a system.

A service approach that hopes to build a long-term and sustainable relationship with customers that has value for both the customer and the company.

The coordination of all activities across the entire supply chain.

A system that integrates multiple business functions from purchasing to sales, billings, accounting records, and payroll.

A branch of mathematics that examines competitive situations in which one’s outcomes may be influenced or dictated by the decisions of other players.

A game in which the total benefits for all participants total zero.

A game that potentially has net results other than zero.

Outcomes where there can be multiple winners.

A comprehensive series of metrics to evaluate the performance of a supply chain’s operations.