Aesthetics and Delivery

7

Learning Objectives

- Describe public speaking as an art form

- Define aesthetics

- Introduce strategies to create an aesthetic experience

- Preview chapters in Part 3

In Chapter 1, we asked that you picture your favorite public speaker. Who is it? A favorite teacher? A well-known politician? An artist? Close your eyes and bring that image back to the surface. What’s happening? How do you feel? What is captivating about the speaker? What language choices did they make? How did they sustain your attention for so long?

If you’re having trouble thinking of one speaker, imagine your ideal public speaking experience. You sit through a presentation feeling interested and intrigued by a unique argument. You hadn’t thought about that topic before, and you now feel called in by the speaker to consider their ideas in more detail.

“How did they do that?” you might ask yourself. “How did they make me feel that way?”

Maybe you were persuaded by their evidence. Maybe they were clear and effective in their organization. But what else?

Like we mentioned in Chapters 3 and 4, we are inundated with information, including well-researched ideas about our world. These, though, don’t always spark our attention or draw us in. Good speakers can, in addition to crafting a well-reasoned argument, create a captivating, aesthetic experience for the audience through their delivery, language, and style. Public speaking is embodied, and audiences make sense of the speaker’s ideas through the embodiment of their argument.

It may be difficult to quantify or describe, but good speakers create a felt sense with their audience. Something happens where the audience is captivated by the speaker’s delivery of their argument—we call this an aesthetic experience. As an audience, you aren’t just empty cups getting filled with the speaker’s ideas— you are experiencing their argument live, through their embodiment, in a context, and with others. It is an experience, and good speakers make aesthetic choices that leave you with a felt sense of their advocacy. They leave you captivated by the argument and energy of their ideas.

In this chapter, we consider how a speaker can enhance arguments by creating a captivating experience for the audience through aesthetic choices. While the remaining chapters in Part 4 will look at specific components of aesthetics, this chapter aims to provide an overview of public speaking as an aesthetic experience.

Let’s get started with a description of aesthetics.

Introducing Aesthetics

You may be wondering, “what does aesthetics mean?” It may be a word that you’ve heard to describe something physically beautifully—a piece of art, an outdoor landscape.

A simple Google search defines aesthetics as “artistically valid or beautiful” (The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language) or “pleasing in appearance” (Merriam-Webster). We often think of a sunset as being aesthetically beautiful or providing us with an aesthetically pleasing experience. With a vast spectacle of blues, violets, yellows, reds are warmly cast across the skyline, sunsets are a sensory experience with immense beauty. We often like to experience a pleasant sunset.

Philosopher Alexander Baumgarten extended aesthetics to also mean the study of good art or good taste (Caygill, 1982). In other words, what makes something aesthetically pleasing? How can we study those things to re-create those sensations?

Okay, so what does this all mean for public speaking?

It means that aesthetics is not just an experience of beauty, it’s the study and enactment of art that leads to sensation, or a felt sense. When you audience a speech and are left with a felt sense, you might ask, “What created that experience?” “What decisions were made that led to that sensation?” Aesthetics allows us to think through the sensations created through art.

You may not view public speaking as an art, but public speaking’s history is grounded in viewing speaking— what we say and how we say it—as an art form.

Public Speaking as an Art: The Rhetorical Tradition

In classical rhetoric, elocution was the art of delivering speeches, where pronunciation, vocal delivery, and gestures were key to effective public speaking. Elocutionists viewed vocal delivery as important because

those qualities are what allowed passions and emotions to be communicated (Goldsbury and Russell, 1844). In elocution, how you said what you said became just as important as what you said. The how was key to artful delivery.

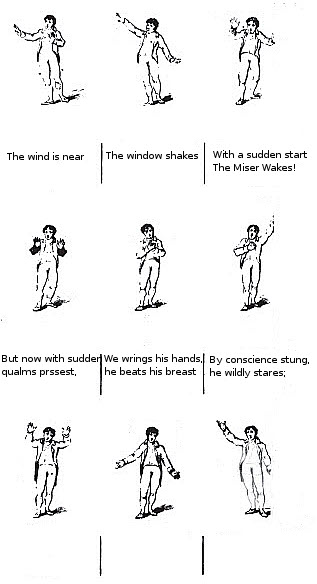

However, elocution was highly formalized (see Figure 7.1) – there were pamphlets of preferred gestures, for example, and strict grammatical expectations. Elocutionists were too focused on how something was delivered from a universal, mechanical perspective. The what was often lost.

So, “elocution” doesn’t fully represent public speaking because, as Chapter 1 discussed, public speaking involves the delivery of a memorable and important message that you’re advocated for. Good public speaking involves a balance between the how and the what.

While the historical practices of elocution have changed, the current practices remind speakers to concentrate on nonverbal communication, the body, and visual rhetoric (Munsell, 2011, p. 17). It reminds us that public speaking is an art – it’s aesthetic.

Criticizing Elocution

The classical rhetorical canons of style and delivery also viewed rhetoric as an art. Public speaking is rooted in rhetoric (as Chapter 1 detailed), and rhetorical scholars have argued for public speakers to attend to style – how you effectively craft and execute your ideas, like word choice— and delivery – how information is delivered.

Think about your own style and delivery. How do you dress? What are the quarks in your personality? How do you like to represent your ideas? We all embody our own style, and we often make stylistic (or aesthetic) choices based on who we’re speaking to and where we’re speaking. We use our style to deliver information that informs and influences others.

In rhetoric, style and delivery are similar—style asks that you consider how to present your information to the specific audience that you’re speaking. This includes: being clear with your language so that everyone understands, establishing your ethos as an educated and credible speaker, and using figures of speech to elevate the language. Delivery is the mechanics used to convey a message rather than the words itself. In classical rhetoric, an eloquent speaker was a credible speaker, so delivery was an important part of the public speaking process.

However, similar to elocution, delivery doesn’t fully describe the embodiment of a speech or the experience that’s created. Think about a pizza delivery person. What’s their job? Their job is to deliver the pizza to you, the audience; they are the vessel that provides the pre-packaged deliciousness. For public speaking, delivery can assume a pre-packaged speech (the argument) that you are merely transmitting to the audience. We know from Chapter 1, though, that public speaking is a constitutive process that makes meaning, and your embodiment is part of that meaning, not merely a vessel of delivery.

So, aesthetics extends classical rhetorical insight about public speaking as an art and provides a broader picture by asking, “what sensations do you want the audience to experience?” “How do we get there?”

Applying Aesthetics in Public Speaking

In our current view of public speaking, aesthetics combines rhetorical traditions – elocution, style, and delivery—to captivate and evoke a felt experience for and with a live audience.

Aesthetics is interested in the overall experience for the audience, by looking at:

- Verbal delivery: how language paints a picture through vivid language or storytelling, the use of emotions, and the embodied delivery of content through projection, rate, enunciation, and more. (Discussed more in Chapter 8)

- Nonverbal delivery: how body language and nonverbal communication, including facial expressions, gestures, and movement in the space, influences the audience’s understanding and perception of your message. (Discussed more in Chapter 9)

- Presentation aids: how presentation aids can enhance the experience by emphasizing, clarifying, or enhancing an idea for the audience. (Discussed more in Chapter 10)

- Space: how the speaking context and space might add or detract from the aesthetic delivery of your content. (Discussed more in Chapter 11)

Aesthetics asks the speaker to consider the entire context, including the space, set-up, audience location – all elements that influence how the audience experiences the speech overall. We’ll dive more into this below. Like we mentioned, public speaking is highly embodied, and experiencing information through a person and through their body is highly sensational and artistic.

As a speaker, you will make aesthetic choices—based on verbal delivery, for example— that create an overall experience for the audience.

Creating an Aesthetic Experience

Creating an aesthetic experience means setting the scene and stage for your audience to feel good or bad; to move your audience toward something by motivating them to act or think. Cupchik and Winston (1996) describe an aesthetic experience as a process where an audience’s attention is focused while everyday concerns are temporarily forgotten. The goal is to hold your audience’s attention; to invite them to focus in. After all, public speaking happens with and for an audience.

Think about a wedding ceremony, for example. Weddings are often aesthetically pleasing – they are beautiful and artistic. If you’re part of the wedding, you make decisions that will provide your audience with an aesthetic experience: there are flowers, lights, rehearsed movement, and speaking– all of these components add to how the wedding is received. To guarantee a successful experience that meets your audience’s expectations, you focus on the elements that you can control, like where the chairs are, what stories are told in the ceremony, and how long the cocktail hour is.

As a speaker, you also make aesthetic choices around controllable components, like verbal deliver, to captivate and evoke a felt experience for and with your audience.

“How do I decide what choices to make?” you might be wondering.

Be appraised of the public speaking context. Different public speaking contexts include norms and expectations that will influence the type of aesthetic experience you can create.

If you’re giving a commencement speech, there are speaking norms and contextual constraints – this information will help you determine what’s aesthetically possible and what’s expected (see Image 7.2). Those expectations differ from a policy-focused persuasive speech at a political campaign rally.

Once you’re comfortable with the context, you can ask, “What am I trying to motivate the audience to do?” Sounds, verbal cadence, embodiment of gestures, and presentation aids are all aesthetic choices that can assist you in accomplishing that goal.

The following chapters will help you tease out those different components in more detail. The more conscious you are of your delivery, including verbal and nonverbal components, the more confident you can become about creating your ideal aesthetic experience.

Aesthetics as the Audience

Because aesthetic experiences are created with audiences, you play a role in that experience when you’re in the audience. Yes, a public speech includes a designated speaker. Yes, they are the primary focus and speaker, but an aesthetic experience is not created alone—it is always collective because it requires others and it is contextual. The communication context is being created together.

As an audience member, you are participating in the experience. Remember to be conscious of your nonverbal feedback: how are you participating nonverbally (or verbally, if requested)? How are you influencing the aesthetic experience for other audience members?

One of our authors attended a speech and, despite their best attempts, couldn’t stay focused on the speaker because an audience member had bought a tablet and was playing a game nearby. The game became part of the aesthetic experience and left a negative sensation. Similarly, an an audience, we are used to clapping at modern concerts, but when you’re in the audience to a symphony, clapping between movements is considered rude. As an audience, you can contribute in aesthetically meaningful ways.

Conclusion and What’s Next?

So far, you should have a working vocabulary around aesthetics and creating an aesthetic experience for your audience.

The following chapters in Part 3 are deeper investigations around categories of aesthetics in public speaking. In the following chapters, we will walk through best practices in delivery, beginning with your verbal delivery. While we will discuss best practices (and your instructor will likely set clear delivery standards in their grading rubrics), it’s important that you rehearse; rehearse more; watch yourself give a speech – these allow you to adapt and develop your own aesthetic style when giving a public speech.

Media Attributions

- Elocution © Gilbert Austin

- Commencement-address-keynote-speaker © Sullskit is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license