Advocacy and Audiences

2

Learning Objectives

- Describe how to analyze the formal audience

- Consider implied or implicated audiences

- Explain stereotypes and ethnocentrisms

- Explain ways an individual can improve their listening when in an audience

We are fans of standup comedy. A well-developed standup routine can leave us engaged and on the edge of our seat; it can leave us feeling like each joke was crafted for us.

Sadly, many of us have sat through less-engaging routines where awkward silence fills the space after an ill-placed punchline.

“Wow. Wrong audience,” the comic often nervously responds.

Similar to standup, audiences are central to public speeches. They are the main focus of our advocacies, and when we know more about our audiences, we can craft messages that effectively inform or move them toward action. We can craft messages to call them in.

You’ll notice that this book’s title includes “call in,” and you may wonder, what does that mean? When you speak out, you’re not speaking into thin air; instead, you’re inviting the audience to listen—you’re calling them in. To call in means creating a message that both relates to and implicates your audience; it is to summon. Paul Watzlawick, Janet Beavin, and Don Jackson (1967) write that communication always involves a content dimension and a relationship dimension. Nowhere does that become more important than working to call our audience in. You are not using the speech to dump a large amount of content on the audience; you are making that content important, meaningful, and applicable to them. Additionally, the way the audience perceives you and your connection to them—such as whether there is mutual trust and respect—will largely determine your success with the audience. The speaker must respect the audience as well as the audience trusting the speaker for “calling in” to be a success.

As you can see, calling an audience in is a process, and a complex one at that. In this chapter, we explore audiences in public speaking. To start, we answer the question: what’s an audience, anyway?

What’s an Audience?

In this chapter, we approach the audience in three ways.

First, by “audience” we mean the explicit audience that’s present when a speaker directs their message. The people sitting in chairs. Because public speeches require an audience, and because public speakers are asking the audience to listen to an argument, it’s important to analyze the group receiving a message – who you are speaking to. This is your explicit audience.

In addition, there are implied or implicated audiences who may or may not be present. Like we discussed in Chapter 1, public speaking is presenting an advocacy that engages for and with your community. When you are representing a group, culture, or an individual, they become an implicit audience. You are responsible for how you communicate about that audience or other groups who may be implicated by the advocacy.

Finally, you will be an audience member. The third dimension of “audience,” then, is you! As an audience member, your primary goal is to listen and reflect on what the speaker is presenting. Listening isn’t as easy as it sounds. So, we’ll also discuss listening, barriers, and best practices.

Who you’re speaking to, who you’re speaking for or about, and when you’re receiving a message are all components of the “audience.” Below, we’ll begin discussing analyzing the first dimension of audience: the explicit, formal group that listens to your message.

Speaking to an Audience

Public speaking requires an audience. After all, when speaking, your goal is to share a message that’s relevant and provide unique insight that will benefit those present. To accomplish that goal, you need to get to know the explicit audience you’re speaking to: you need to analyze them.

You may wonder, “Okay, but how do I do that?” Information gathering is the answer.

The more information you have, the more you’re able to isolate any overlapping beliefs, values, or goals that the audience shares. Audiences are unique, diverse, and sometimes unpredictable; information gathering will allow you to select an argument that’s most relevant to what your audience needs.

By needs, we mean identifying important deficiencies that we are motivated to resolve.

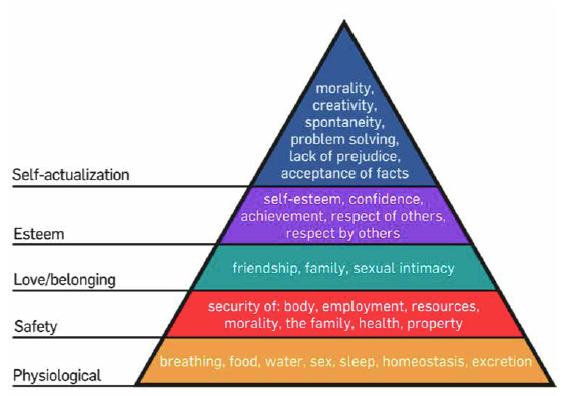

You may already be familiar with the well-known diagram, Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs—a framework to think about human needs. It is commonly discussed in the fields of management, psychology, and health professions. A version of it is shown in Figure 2.1 (More recent versions show it with 8 levels.) In trying to understand human motivation, Maslow theorized that, as our needs represented at the base of the pyramid are fulfilled, we move up the hierarchy to fulfill other types of need (McLeod, 2014).

Figure 2.1

According to Maslow’s theory, our most basic physiological or survival needs must be met before we move to the second level, which is safety and security. When our needs for safety and security are met, we move up to relationship or connection needs, often called “love and belongingness.” The fourth level up is esteem needs, which could be thought of as achievement, accomplishment, or self-confidence. The highest level, self-actualization, is achieved by those who are satisfied and secure enough in the lower four that they can make sacrifices for others. Self-actualized persons are usually thought of as altruistic or charitable.

Unfortunately, humans aren’t always aware of what their needs are, so part of your task is learning about the audience and isolating needs that they may or may not be conscious of. For example, you’re reading out of an open textbook: this book was free of charge. Until you were assigned the book, you may not have been aware that open textbooks (or open educational resources) were an option. It was a need that you weren’t conscious of. A good speaker highlights the presence of a need by relating that issue to their audience.

When addressing an audience, determining what they need and where that need falls on the pyramid can influence how you make content that’s relatable – it can help you call them in. Diving deeper into the speaking context, audience demographics, and audience values all provide necessary information to identify needs and craft relevant arguments.

Researching the Context

Analyzing your audience needs begins by asking top level questions about the public speaking context: why will your audience be there? What’s bringing them together? What’s motivating them to attend? Determining why your audience will be in attendance can help uncover more about who they are.

If you aren’t familiar with the why—why the audience is attending— conduct preliminary research. Use resources that are at your disposal to learn more and dig deep. If you’re speaking at a formal convention, for example, what’s the convention about? Is there a convention theme? Does the convention provide insight into past convention participants? How many people does the event accept?

Your research can help identify what’s bringing the audience together. You might learn, for example, that conference attendees share a common career, participate in a common organization, or have a similar hobby. When you speak in a class, the course content (or university requirement) brings the audience together. If you’re at a neighborhood meeting, the audience likely lives in that neighborhood, and you can learn about the key issues being discussed at the meeting.

As you research, try to determine what’s motivating your audience to be present. Identifying motivations can help assist in identifying what your audience needs or what needs they’re trying to fulfill.

Understanding Audience Demographics

A second information gathering strategy is looking at audience demographics.

Demographics – sociocultural characteristics that identify and characterize populations – are common ways of organizing and gathering data about groups of people. Have you ever taken a survey? Researchers often ask demographic information of participants to determine how answers may change between sub-groups (based on different demographics). In the United States, for example, data might track the average age or the average socioeconomic standing of an incoming college student.

Demographics can be a helpful source of information gathering. If you’re aware of common audience demographics, you can gather information that might glean insights into common beliefs, attitudes, or responses to a topic. Using data and research, like a survey or experimental finding, can help educate you about particular demographic groups that may be in your audience. Figure 2.2 introduces common audience demographics and their corresponding descriptions.

|

Audience Demographics and Descriptions |

|

|

Education |

The kind of information and training a person has been exposed to. |

|

Family Status |

The self-identified status of an individual, including married, single, open, divorced. May include children. |

|

Gender Identity |

The self-identified presentation of a gender, including women, men, (cis or trans), and gender non-conforming. |

|

Occupation |

A job, career, or industry that one performs. |

|

Race |

The self-identification with one or more social groups, such as White, African American, Native Hawaiian. Social groups are often defined by common ancestry, cultural markers, or physical characteristics. |

|

Religion |

Beliefs and practices about the transcendent, deity, and the meaning of life; can be thought of as an affiliation and a commitment. |

|

Sexual Orientation |

The self-identification of who an individual based no whom they have relationships with or attraction toward. |

|

Socio-Economics |

A person or group’s economic standing in relation to others. |

| Figure 2.2 | |

Other demographics include ethnicity, gender expression, spirituality, family structure, ability/disability, region or nationality, and generation or age.

Rather than stable categories, demographics are dynamic, changing, and contextual.

Religion, for example, is a porous concept that encompasses a wide range of formal and informal practices. If you gather information about your audience, and you determine that your audience is “religious,” make sure that you aren’t assuming a particular religious affiliation or making assumptions about what the category of religion infers.

While using demographic information can be helpful, it can also lead to stereotyping or relying on totalizing conclusions. Stereotyping is generalizing about a group of people and assuming that because a few persons in that group have a characteristic, all of them do. If we were sitting near campus and saw two students drive by hectically and said, “All college students are bad drivers,” that would be stereotyping. Sadly, our stereotypical thoughts are often reinforced when a group behavior is observed. Every time we see a student (or who we perceive to be a student) driving hectically, we use that observation to support our stereotypical thought. Stereotypes have strongholds, so we likely don’t “count” observations where students are driving safely.

We know what you’re thinking: “I never stereotype.” But we all do. Rather than pretend that stereotypes aren’t part of our cultural narrative, use reflective and reflexive thinking (from Chapter 1) to evaluate when a stereotypical thought or idea arises. This includes being reflexive when using demographic information to inform your speech content.

Similarly, individuals are part of multiple demographic categories, not just one. Think about yourself and your identity. What are key parts? What types of demographics make you, you? You aren’t just one category. Isolating one demographic to represent the whole person is totalizing. Totalizing is taking one characteristic of a group or person and making that the “totality” or sum total of what that person or group is. Totalizing often happens to persons with disabilities, for example; the disability is seen as the totality of that person, or all that person is about. This can be both harmful to the relationship and ineffective as a means of communicating.

Demographics, then, are part of the information gathering process. But researching your audience’s demographics doesn’t mean learning one category and stopping there. Instead, think about your audience as a complex matrix, and demographics are one component of the grid. To gain a deeper insight into the matrix, search for insight about your audience’s beliefs, attitudes, and values.

Beliefs, Attitudes, and Values

In Chapter 1, we discussed that communication both creates and sustains cultures. All of us are part of different cultures and, through communication, we learn about what those cultures believe and value, often adopting those beliefs for ourselves. For example, why are you in college? It’s likely that you are part of a culture that values education and believes that education will lead to your betterment.

In some cases, groups with similar demographics can hold similar beliefs, attitudes, or values, but not always. Rather than map beliefs onto your demographics, use your research and information gathering to determine what kind of inner beliefs, attitudes, and values your audience may hold.

Beliefs are “statements we hold to be true” (Daryl Bem, 1970). Notice this definition does not say the beliefs are true, only that we hold them to be true and, as such, they determine how we respond to the world around us. Stereotypes are a kind of belief: we believe all the people in a certain group are “like that” or share a trait. Beliefs, according to Bem, come from our experience and from sources we trust. Therefore, beliefs are hard to change—not impossible, just difficult.

Beliefs are hard to change because of:

- stability—the longer we hold them, the more stable or entrenched they are;

- centrality—they are in the middle of our identity, self-concept, or “who we are”;

- saliency—we think about them a great deal; and

- strength—we have a great deal of intellectual or experiential support for the belief or we engage in activities that strengthen the beliefs.

For example, we (the authors) believe that all genders should be treated equally. This is a belief that we’ve established based on personal experience and cultural narratives. We believe this to be true. This belief informs how we treat people, the things we care about, and what we advocate for. This is a very strong belief, so it would be difficult for a speaker to persuade us otherwise, but would be important information for a speaker to know.

Values are goals we strive for and what we consider important and desirable. However, values are not just basic wants. A person may want a vintage sports car from the 1960s, and may value it because of the amount of money it costs, but the vintage sports car is not a value; it represents a value of either:

- nostalgia (the person’s parents owned one in the 1960s and it reminds them of good times),

- display (the person wants to show it off and get “oohs” and “ahs”),

- materialism (the person believes the adage that the one who dies with the most toys wins),

- aesthetics (the person admires the look of the car and enjoys maintaining the sleek appearance),

- prestige (the person has earned enough money to enjoy and show off this kind of vehicle), or

- physical pleasure (the driver likes the feel of driving a sports car on the open road).

In the United States, for example, you might speak to an audience that values monetary security and success. This value is informed by a belief. It’s likely, for example, that values around monetary success and prestige are rooted in beliefs that individual hard work can achieve success in a capitalist society. If you can identify a value, ask: what could be fueling that value? What beliefs?

Finally, attitude is defined as a positive or negative response to a person, idea, object, or policy. How do you respond when you hear the name of a certain singer, movie star, political leader, sports team, or law in your state? Your response will be either positive or negative, or maybe neutral if you are not familiar with the object of the attitude. Where did that attitude come from? Does that person, idea, or object differ from you in values and beliefs?

Let’s extend our monetary example from above. If you speak to an audience who believes in capitalism and values monetary, individual success, it may be unwise to mention “socialism” as the audience may have a negative attitude to socialism as a concept.

Consider this second example. Pretend that you’re speaking to a campus audience and, currently, the university has a very popular campus leader. The audience likely has a positive attitude toward that leader, so it would be beneficial to quote that person in the speech itself.

While discrete categories, beliefs, values, and attitudes are often intertwined, and knowing more about these categories can add to your understand of who the audience is. Knowing who they are means identifying their needs and determining how and why your speech is relevant.

Speaking for an Audience

Gathering information about your explicit audience—the formal audience you’re speaking in front of – is certainly important. The second audience to consider is the implied or implicated audience. In this section, we discuss how we talk about who we’re talking about: how we’re talking about the groups that are either represented and/or affected by our message.

Let’s use a state congressional hearing as an example. Imagine a group of congress people meeting to advocate for a bill’s passage that decreases environmental protections for a city in that state. The bill’s author stands and advocates passionately for the bill’s passage, noting that reducing the environmental protections would allow more business and jobs in the area. The speaker works to craft an argument that’s compelling for the explicit audience – the audience of other congress people who are present.

However, there are other implied audiences – the communities that would be most impacted by environmental pollution; residents who live in the area; business owners themselves. These audiences are important because they are both represented in the advocacy and would be impacted by the results of the speech. They may not, though, be part of the explicit audience.

To determine your implied audience, ask: Who are you speaking about/advocating for? Are you sharing information about a culture, group, or individual? If so, who? Are you sharing information that will impact a culture, group, or individual? If so, who?

It may seem odd to consider audiences that are implied or not present. After all, isn’t the explicit audience who you’re trying to inform, persuade, or entertain? Yes, your explicit audience is important, but as we discussed in Chapter 1, communication is constitutive. When you communicate or advocate for an idea, you are participating in world-making. The way that you talk or represent groups, cultures, or individuals has lasting impacts, even outside your explicit speech event. It can impact your implied audience. So, the “talk” about an implied audience matters.

Asking ourselves to be accountable to implied audiences also encourages us to use ethical communication, pay attention to power, and reduce stereotypes.

For example, if a speaker advocated to intervene in a country through military means, they might argue that “The United States needs to intervene because, right now, the other country is exhibiting barbaric tendencies.”

First, ask: Who is the implied audience in this example? What audiences would be implicated (but are likely not present)? A clear implied audience includes the non-U.S. population or cultural group, i.e. “the other country.”

Second, ask, how has this group been represented? What kind of talk is being used to describe these implied audiences? You’ll notice that “barbaric” was used to describe individuals in this culture. In this instance, “barbaric” seems to imply that the United States intervention is justified; barbaric seems bad and, alternatively, the United States does not exhibit those “barbaric tendencies” so, the U.S. may be best suited to intervene.

However, this explanation is using ethnocentrism—or the belief that one’s own culture is superior—as part of their argument. This type of talk should be avoided because it often represents other cultures in unethical, stereotypical, or unjust ways. If the speech’s argument requires an ethnocentric perspective, the argument isn’t based on good reasons (we’ll discuss this more in Chapter 5).

So far, we’ve discussed your implied and impacted audience as groups that are discussed, represented, or implicated by your speech. A final implied audience includes any groups, cultures, or an individual’s ideas that you’re using.

Have you ever had a friend who re-tells your joke but doesn’t give you credit? Not cool! The same is true for speech advocacies. Any time you use or adapt an idea from a group or individual, you must give that implied audience credit. Failing to do so is known as plagiarism, or representing someone’s ideas as your own (more on this in Chapter 4). Once you’ve finished writing an advocacy, make sure to double-check that anyone and everyone’s information has been properly cited.

Identifying your implied audience can take time, but don’t worry. We’ll continue building critical thinking skills throughout the book to practice ethical and just public speaking with your explicit and implied audience in mind.

Listening in the Audience

The third component of “audience” includes you! You will be an audience member many, many times, and you should take that job seriously. Your job in the audience is to listen and ethically reflect on what the speaker is saying. In this section, we explore listening as a key audience concept.

Listening is not the same thing as hearing. Hearing is a physical process in which sound waves hit your ear drums and send a message to your brain. You may hear cars honking or dogs barking when you are walking down the street because your brain is processing the sounds, but that doesn’t mean that you are listening to them. Listening implies an active process where you are specifically making an effort to understand, process, and retain information.

In an audience, listening can be a difficult process. Unlike reading, which allows you to re-read a passage, you often have one chance to listen to an argument in a speech. Many studies have been conducted to find out how long we remember oral messages, and often the level of memory from oral communication is not very high (Bostrom & Bryant, 1980). The solution? Try to enact different listening techniques and reduce your barriers to listening.

Types of Listening

In this section, we will focus on types of listening. Ideally, we recommend working toward comprehensive or active listening, which is listening focused on understanding and remembering important information from a public speaking message. There are other “types” of listening, based on the context and purpose.

The first is empathetic listening, or understanding the feelings and motivations of another person, usually with a goal of helping. For example, if a friend says that she is thinking about dropping out of college at the end of the semester, you would want to listen for the reasons and feelings behind her choice, recognizing that you might need to ask sensitive questions and not just start telling her what to do or talk about your own feelings.

The second type of listening is appreciative, which takes place while listening to music, poetry, or literature, or watching a play or movie. For example, knowing that the melodies of classical musical have a certain A-B pattern informs us how to listen to Mozart. To be good at this kind of listening, it helps to study the art form to learn the patterns and devices.

The third type is critical listening. In critical listening the audience member is evaluating the validity of the arguments and information and deciding whether the speaker is persuasive and whether the message should be accepted. This often occurs when listening to persuasive arguments.

What can a speaker do to encourage listening for an audience?

Planned redundancy refers to purposeful ways of repeating and restating parts of the speech to help the audience listen and retain the content. You might not be able to cover or dump a great deal of information in a speech (and you probably shouldn’t), but you can make the information meaningful through planned redundancy and repeating or underscoring key components of your argument.

A speaker can also help the audience’s listening abilities by using presentation aids (discussed in Chapter 10), stories and examples (discussed in Chapter 5), audience interaction or movement at key points in the speech (discussed in Chapter 9), and specific attention-getting techniques (discussed in Chapter 6).

In short, listening is hard work, but you can meet your audience half way by using certain strategies and material to make listening easier for them. At the same time, an audience member has a responsibility to pay attention and listen well.

In the next section, we will look at how you can improve your listening ability in public speaking situations.

Barriers to Effective Listening

Since hearing is a physiological response to auditory stimuli, you hear things whether you want to or not. Just ask anyone who has tried to go to sleep with the neighbor’s dog barking all night. However, listening–really listening– is intentional and hard work. And there are three common barriers to be conscious of.

Noise – physical and mental – is the first barrier to listening. We have constant mental distractions in our lives, something that you might not even be aware of if you have always lived in the world of Internet, cell phones, iPods, tablets, and 24/7 news channels. We are dependent on and constantly wired to the Internet. Focus is difficult. Not only do electronic distractions hurt our listening, but life concerns can distract us as well. An ill family member, a huge exam next period, your car in the shop, deciding on next semester’s classes—the list is endless.

Physical noisiness and distractions also contribute to difficulty listening. Perhaps someone next to you is on their cell phone, and you hear the constant click of their keyboard. Perhaps they are whispering to each other and impeding your ability to hear the speaker clearly. The physical environment can also exert noise. Maybe it’s raining outside or someone is vacuuming through the door.

Confirmation bias is a second barrier to listening. This term means “a tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions” (Nickerson, 1998). Although the concept has been around a long time, we are more aware of confirmation bias today. It leads us to listen to news outlets and Internet sources that confirm what we believe already rather than being challenged to new ways of thinking by reading or listening to other sources of information. It can cause us to discount, reject, or reinterpret information to fit our preconceptions.

Finally, information processing is the third barrier. Our minds can usually process much faster than a speaker can speak clearly. We may be able to listen, when really trying, at 200 words per minute, but few speakers can articulate that many words clearly; an average rate for normal speech is around 100-120 (Foulke, 1968). That leaves a great deal of time when the mind needs to pull itself back into focus. During those gaps, we might find it more enjoyable to think of lunch, the new person we are dating, or our vacation at the beach.

These are all the possible obstacles to listening, but there might also be reasons that are particular to you, the listener. We often go into listening situations with no purpose; we are just there physically but have no plans for listening. We go in unprepared. We are tired and mentally and physically unready to listen well. We are hungry or fatigued. We do not sit in a comfortable position to listen. We do not bring proper tools to listen, specifically to take notes. So, what do we do?

Intentional Listening

As audience members, barriers prohibit our ability to absorb information that could benefit us.

Your own barrier might be not coming prepared, being quick to prejudge, or allowing gadgets to distract you. Obviously, recognizing the cause of your poor listening is the first step to becoming a better listener. Here are some steps, in summary:

- Practice the skill. Believe that good listening and improving your own listening are important. You would not want to be called upon in a meeting at work when you were daydreaming or being distracted by a cell phone. Consider listening to speeches in a prepared manner and practice listening as a skill.

- Practice reflexive listening. Since it is so easy to react to a speaker’s ideas with confirmation bias, go into listening knowing that you might disagree and that the automatic “turn off” tendency is a possibility. In other words, tell yourself to keep an open mind.

- Be prepared to listen. This means putting away mobile devices, having a pen and paper, and situating yourself physically to listen (not slouching or slumping). Have a purpose in listening. There is actual research to indicate that we listen better and learn/retain more when we take notes with a pen and paper then when we type them on a computer or tablet (Mueller & Oppenheimer, 2014). Situate yourself by making decisions that will aid in your listening.

- When taking notes, keep yourself mentally engaged by writing questions that arise. This behavior will fill in the gaps, create an interactive experience with the speaker, and reduce the likelihood that your mind will wander. However, taking notes does not mean “transcribing” the speech or lecture. Whether in class or in a different listening situation, do not (try to) write everything the speaker says down. Instead, start with looking for the over-all purpose and structure, then for pertinent examples of each main point. Repetition by a speaker usually indicates you should write something down.

Conclusion

Audiences are central to a speaker’s success. All 3 audience dimensions are key to consider, whether you’re speaking or listening. Use this chapter throughout the public speaking process to create a relevant argument that’s engaging to your audience. Work to call them in: to summon them to actively listen to your advocacy.