Speechwriting

9 Structure and Organization

Writing a Speech That Audiences Can Grasp

In this chapter . . .

For a speech to be effective, the material must be presented in a way that makes it not only engaging but easy for the audience to follow. Having a clear structure and a well-organized speech makes this possible. In this chapter we cover the elements of a well-structured speech, using transitions to connect each element, and patterns for organizing the order of your main points.

Have you had this experience? You have an instructor who is easy to take notes from because they help you see the main ideas and give you cues as to what is most important to write down and study for the test. On the other hand, you might have an instructor who tells interesting stories, says provocative things, and leads engaging discussions, but you have a tough time following where the instruction is going. If you’ve experienced either of these, you already know that structure and the organized presentation of material makes a big difference for listening and learning. The structure is like a house, which has essential parts like a roof, walls, windows, and doors. Organization is like the placement of rooms within the house, arranged for a logical and easy flow.

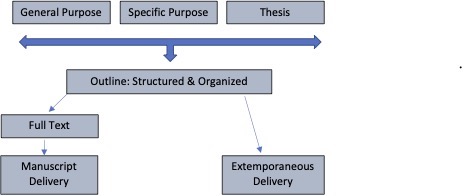

This chapter will teach you about creating a speech through an outlining process that involves structure and organization. In the earlier chapter Ways of Delivering Speeches, you learned about several different modes of speech delivery: impromptu, extemporaneous, and manuscript. Each of these suggests a different kind of speech document. An impromptu speech will have a very minimal document or none at all. An extemporaneous delivery requires a very thorough outline, and a manuscript delivery requires a fully written speech text. Here’s a crucial point to understand: Whether you plan to deliver extemporaneously or from a fully written text. The process of outlining is crucial. A manuscript is simply a thorough outline into which all the words have been written.

Four Elements of a Structured Speech

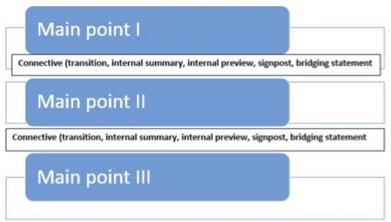

A well-structured speech has four distinct elements: introduction, body, connective statements, and conclusion. While this sounds simple, each of these elements has sub-elements and nuances that are important to understand. Introductions and conclusions are complex enough to warrant their own chapter and will be discussed in depth further on.

Introduction and Conclusion

The importance of a good introduction cannot be overstated. The clearer and more thorough the introduction, the more likely your audience will listen to the rest of the speech and not “turn off.” An introduction, which typically occupies 10-15% of your entire speech, serves many functions including getting the audience’s attention, establishing your credibility, stating your thesis, and previewing your main points.

Like an introduction, speech conclusions are essential. They serve the function of reiterating the key points of your speech and leave the audience with something to remember.

The elements of introductions and conclusions will be discussed in the following chapter. The remainder of this chapter is devoted to the body of the speech and its connectors.

The Body of a Speech

The body of a speech is comprised of several distinct groups of related information or arguments. A proper group is one where a) the group can be described in a single clear sentence, and b) there’s a logical relationship between everything within it. We call that describing sentence a main point. Speeches typically have several main points, all logically related to the thesis/central idea of the speech. Main points are followed by explanation, elaboration, and supporting evidence that are called sub-points.

Main Points

A main point in a speech is a complete sentence that states the topic for information that is logically grouped together. In a writing course, you may have learned about writing a paragraph topic sentence. This is typically the first sentence of a paragraph and states the topic of the paragraph. Speechwriting is similar. Whether you’re composing an essay with a paragraph topic sentences or a drafting a speech with main points, everything in the section attached to the main point should logically pertain to it. If not, then the information belongs under a different main point. Let’s look at an example of three main points:

General Purpose: To persuade

Specific Purpose: To motivate my classmates in English 101 to participate in a study abroad program.

Thesis: A semester-long study abroad experience produces lifelong benefits by teaching you about another culture, developing your language skills, and enhancing your future career prospects.

Main point #1: A study abroad experience allows you to acquire firsthand experience of another culture through classes, extra-curricular activities, and social connections.

Main point #2: You’ll turbocharge your acquisition of second language skills through an immersive experience living with a family.

Main point #3: A study abroad experience on your resume shows that you have acquired the kind of language and cultural skills that appeal to employers in many sectors.

Notice that each main point is expressed in a complete sentence, not merely #1 Culture; #2 Language; #3 Career. One-word signals are useless as a cue for speaking. Additionally, students are often tempted to write main points as directions to themselves, “Talk about the health department” or “Mention the solution.” This isn’t helpful for you, either. Better: “The health department provides many services for low-income residents” says something we can all understand.

Finally, the important thing to understand about speechwriting is that listeners have limits as to how many categories of information they can keep in mind. The number of main points that can be addressed in any speech is determined by the time allotted for a speech but is also affected by the fact that speeches are limited in their ability to convey substantial amounts of information. For a speech of five to seven minutes, three or four main points are usually enough. More than that would be difficult to manage—for both speaker and audience.

Sub-Points

Obviously, creating your main points isn’t the end of the story. Each main point requires additional information or reinforcement. We call these sub-points. Sub-points provide explanation, detail, elaboration, and/or supporting evidence. Consider main point #1 in the previous example, now with sub-points:

Main point #1: A study abroad experience allows you to acquire firsthand experience of another culture through classes, extra-curricular activities, and social connections.

Sub-point A: How a country thinks about education is a window into the life of that culture. While on a study abroad program, you’ll typically take 3-5 classes at foreign universities, usually with local professors. This not only provides new learning, but it opens your eyes to different modes of education.

Sub-point B: Learning about a culture isn’t limited to the classroom. Study abroad programs include many extra-curricular activities that introduce you to art, food, music, sports, and other everyday elements of a country’s culture. These vary depending on the program and there’s something for everyone! The website gooverseas.com provides information on hundreds of programs.

Sub-point C: The opportunity to socialize with peers in other countries is one of most attractive elements of studying abroad. You may form friendships that will last a lifetime. “I have made valuable connections in a country I hope to return to someday” according to a blog post by Rachel Smith, a student at the University of Kansas.[1]

Notice that each of these sub-points pertains to the main point. The sub-points contribute to the main point by providing explanation, detail, elaboration, and/or supporting evidence. Now imagine you had a fourth sub-point:

Sub-point D: And while doing all that socializing, you’ll really improve your language skills.

Does that sub-point belong to main point #1? Or should it be grouped with main point#2 or main point #3?

Connective Statements

Connectives or “connective statements” are broad terms that encompass several types of statements or phrases. They are designed to help “connect” parts of your speech to make it easier for audience members to follow. Connectives are tools that add to the planned redundancy, and they are methods for helping the audience listen, retain information, and follow your structure. In fact, it’s one thing to have a well-organized speech. It’s another for the audience to be able to “consume” or understand that organization.

Connectives in general perform several functions:

- Remind the audience of what has come before

- Remind the audience of the central focus or purpose of the speech

- Forecast what is coming next

- Help the audience have a sense of context in the speech—where are we?

- Explain the logical connection between the previous main idea(s) and next one or previous sub-points and the next one

- Explain your own mental processes in arranging the material as you have

- Keep the audience’s attention through repetition and a sense of movement

Connective statement can include “internal summaries,” “internal previews” “signposts” and “bridging or transition statements.” Each of these helps connect the main ideas of your speech for the audience, but they have different emphases and are useful for different types of speeches.

Types of connectives and examples

Internal summaries emphasize what has come before and remind the audience of what has been covered.

“So far I have shown how the designers of King Tut’s burial tomb used the antechamber to scare away intruders and the second chamber to prepare royal visitors for the experience of seeing the sarcophagus.”

Internal previews let your audience know what is coming up next in the speech and what to expect regarding the content of your speech.

“In this next part of the presentation I will share with you what the truly secret and valuable part of the King Tut’s pyramid: his burial chamber and the treasury.”

Signposts emphasize physical movement through the speech content and let the audience know exactly where they are. Signposting can be as simple as “First,” “Next,” “Lastly” or numbers such as “First,” “Second,” Third,” and “Fourth.” Signposting is meant to be a brief way to let your audience know where they are in the speech. It may help to think of these like the mile markers you see along interstates that tell you where you’re and how many more miles you will travel until you reach your destination.

“The second aspect of baking chocolate chip cookies is to combine your ingredients in the recommended way.”

Bridging or transition statements emphasize moving the audience psychologically to the next step.

“I have mentioned two huge disadvantages to students who don’t have extracurricular music programs. Let me ask: Is that what we want for our students? If not, what can we do about it?”

They can also serve to connect seemingly disconnected (but related) material, most commonly between your main points.

“After looking at how the Cherokee Indians of the North Georgia mountain region were politically important until the 1840s and the Trail of Tears, we can compare their experience with that of the Indians of Central Georgia who did not assimilate in the same way as the Cherokee.”

At a minimum, a bridge or transition statement is saying, “Now that we have looked at (talked about, etc.) X, let’s look at Y.”

There’s no standard format for connectives. However, there are a few pieces of advice to keep in mind about them:

First, connectives are for connecting main points. They are not for providing evidence, statistics, stories, examples, or new factual information for the supporting points of the main ideas of the speech.

Second, while connectives in essay writing can be relatively short—a word or phrase, in public speaking, connectives need to be a sentence or two. When you first start preparing and practicing connectives, you may feel that you’re being too obvious with them, and they are “clunky.” Some connectives may seem to be hitting the audience over the head with them like a hammer. While it’s possible to overdo connectives, it’s less likely than you would think. The audience will appreciate them, and as you listen to your classmates’ speeches, you’ll become aware of when they are present and when they are absent.

Lack of connectives results in hard-to-follow speeches where the information seems to come up unexpectedly or the speaker seems to jump to something new without warning or clarification.

Finally, you’ll also want to vary your connectives and not use the same one all the time. Remember that there are several types of connectives.

Patterns of Organization

At the beginning of this chapter, you read the analogy that a speech structure is like a house and organization is like the arrangement of the rooms. So far, we have talked about structure. The introduction, body, main point, sub-point, connectives—these are the house. But what about the arrangement of the rooms? How will you put your main points in a logical order?

There are some standard ways of organizing the body of a speech. These are called “patterns of organization.” In each of the examples below, you’ll see how the specific purpose gives shape to the organization of the speech and how each one exemplifies one of the six main organizational patterns.

Please note that these are simple, basic outlines for example purposes. The actual content of the speech outline or manuscript will be much further developed.

Chronological Pattern

Specific Purpose: To describe to my classmates the four stages of rehabilitation in addiction recovery.

Main Points:

-

- The first stage is acknowledging the problem and entering treatment.

- The second stage is early abstinence, a difficult period in the rehabilitation facility.

- The third stage is maintaining abstinence after release from the rehab facility.

- The fourth stage is advanced recovery after a period of several years.

The example above uses what is termed the chronological pattern of organization. Chronological always refers to time order. Organizing your main points chronologically is usually appropriate for process speeches (how-to speeches) or for informational speeches that emphasize how something developed from beginning to end. Since the specific purpose in the example above is about stages, it’s necessary to put the four stages in the right order. It would make no sense to put the fourth stage second and the third stage first.

Chronological time can be long or short. If you were giving a speech about the history of the Civil Rights Movement, that period would cover several decades; if you were giving a speech about the process of changing the oil in a car, that process takes less than an hour. Whether the time is long or short, it’s best to avoid a simple, chronological list of steps or facts. A better strategy is to put the information into three to five groups so that the audience has a framework. It would be easy in the case of the Civil Rights Movement to list the many events that happened over more than two decades, but that could be overwhelming for the audience. Instead, your chronological “grouping” might be:

-

- The movement saw African Americans struggling for legal recognition before the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

- The movement was galvanized and motivated by the 1955-1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott.

- The movement saw its goals met in the Civil Rights Act of 1965.

In this way, the chronological organization isn’t an overwhelming list of events. It focuses the audience on three events that pushed the Civil Rights movement forward.

Spatial Pattern

You can see that chronological is a highly-used organizational structure, since one of the ways our minds work is through time-orientation—past, present, future. Another common thought process is movement in space or direction, which is called the spatial pattern. For example:

Specific Purpose: To explain to my classmates the three regional cooking styles of Italy.

-

- In the mountainous region of the North, the food emphasizes cheese and meat.

- In the middle region of Tuscany, the cuisine emphasizes grains and olives.

- In the southern region and Sicily, the diet is based on fish and seafood.

In this example, the content is moving from northern to southern Italy, as the word “regional” would indicate. For a more localized example:

Specific Purpose: To explain to my classmates the layout of the White House.

-

- The East Wing includes the entrance ways and offices for the First Lady.

- The most well-known part of the White House is the West Wing.

- The residential part of the White House is on the second floor. (The emphasis here is the movement a tour would go through.)

For an even more localized example:

Specific Purpose: To describe to my Anatomy and Physiology class the three layers of the human skin.

-

- The outer layer is the epidermis, which is the outermost barrier of protection.

- The second layer beneath is the dermis.

- The third layer closest to the bone is the hypodermis, made of fat and connective tissue.

Topical / Parts of the Whole Pattern

The topical organizational pattern is probably the most all-purpose, in that many speech topics could use it. Many subjects will have main points that naturally divide into “types of,” “kinds of,” “sorts of,” or “categories of.” Other subjects naturally divide into “parts of the whole.” However, as mentioned previously, you want to keep your categories simple, clear, distinct, and at five or fewer.

Specific Purpose: To explain to my first-year students the concept of SMART goals.

-

- SMART goals are specific and clear.

- SMART goals are measurable.

- SMART goals are attainable or achievable.

- SMART goals are relevant and worth doing.

- SMART goals are time-bound and doable within a time period.

Specific Purpose: To explain the four characteristics of quality diamonds.

-

- Valuable diamonds have the characteristic of cut.

- Valuable diamonds have the characteristic of carat.

- Valuable diamonds have the characteristic of color.

- Valuable diamonds have the characteristic of clarity.

Specific Purpose: To describe to my audience the four main chambers of a human heart.

-

- The first chamber in the blood flow is the right atrium.

- The second chamber in the blood flow is the right ventricle.

- The third chamber in the blood flow is the left atrium.

- The fourth chamber in the blood flow and then out to the body is the left ventricle.

At this point in discussing organizational patterns and looking at these examples, two points should be made about them and about speech organization in general:

First, you might look at the example about the chambers of the heart and say, “But couldn’t that be chronological, too, since that’s the order of the blood flow procedure?” Yes, it could. There will be times when a specific purpose could work with two different organizational patterns. In this case, it’s just a matter of emphasis. This speech emphasizes the anatomy of the heart, and the organization is “parts of the whole.” If the speech’s specific purpose were “To explain to my classmates the flow of blood through the chambers of the heart,” the organizational pattern would emphasize chronological, altering the pattern.

Another principle of organization to think about when using topical organization is “climax” organization. That means putting your strongest argument or most important point last when applicable. For example:

Specific purpose: To defend before my classmates the proposition that capital punishment should be abolished in the United States.

-

- Capital punishment does not save money for the justice system.

- Capital punishment does not deter crime in the United States historically.

- Capital punishment has resulted in many unjust executions.

In most people’s minds, “unjust executions” is a bigger reason to end a practice than the cost, since an unjust execution means the loss of an innocent life and a violation of our principles. If you believe Main Point III is the strongest argument of the three, putting it last builds up to a climax.

Cause & Effect Pattern

If the specific purpose mentions words such as “causes,” “origins,” “roots of,” “foundations,” “basis,” “grounds,” or “source,” it’s a causal order; if it mentions words such as “effects,” “results,” “outcomes,” “consequences,” or “products,” it’s effect order. If it mentions both, it would of course be cause/effect order. This example shows a cause/effect pattern:

Specific Purpose: To explain to my classmates the causes and effects of schizophrenia.

-

- Schizophrenia has genetic, social, and environmental causes.

- Schizophrenia has educational, relational, and medical effects.

Problem-Solution Pattern

The principle behind the problem-solution pattern is that if you explain a problem to an audience, you shouldn’t leave them hanging without solutions. Problems are discussed for understanding and to do something about them. This is why the problem-solution pattern is often used for speeches that have the objective of persuading an audience to take action.

When you want to persuade someone to act, the first reason is usually that something needs fixing. Let’s say you want the members of the school board to provide more funds for music at the three local high schools in your county. What is missing because music or arts are not funded? What is the problem?

Specific Purpose: To persuade the members of the school board to take action to support the music program at the school.

-

- There’s a problem with eliminating extracurricular music programs in high schools.

- Students who don’t have extracurricular music in their lives have lower SAT scores.

- Schools that don’t have extracurricular music programs have more gang violence and juvenile delinquency.

- The solution is to provide $200,000 in the budget to sustain extracurricular music in our high schools.

- $120,000 would go to bands.

- $80,000 would go to choral programs.

- There’s a problem with eliminating extracurricular music programs in high schools.

Of course, this is a simple outline, and you would need to provide evidence to support the arguments, but it shows how the problem-solution pattern works.

Psychologically, it makes more sense to use problem-solution rather than solution-problem. The audience will be more motivated to listen if you address needs, deficiencies, or problems in their lives rather than giving them solutions first.

Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

A variation of the problem-solution pattern, and one that sometimes requires more in-depth exploration of an issue, is the “problem-cause-solution” pattern. If you were giving a speech on the future extinction of certain animal species, it would be insufficient to just explain that numbers of species are about to become extinct. Your second point would logically have to explain the cause behind this happening. Is it due to climate change, some type of pollution, encroachment on habitats, disease, or some other reason? In many cases, you can’t really solve a problem without first identifying what caused the problem.

Specific Purpose: To persuade my audience that the age to obtain a driver’s license in the state of Georgia should be raised to 18.

- There’s a problem in this country with young drivers getting into serious automobile accidents leading to many preventable deaths.

- One of the primary causes of this is younger drivers’ inability to remain focused and make good decisions due to incomplete brain development.

- One solution that will help reduce the number of young drivers involved in accidents would be to raise the age for obtaining a driver’s license to 18.

Some Additional Principles of Speech Organization

It’s possible that you may use more than one of these organizational patterns within a single speech. You should also note that in all the examples to this point (which have been kept simple for the purpose of explanation), each main point is relatively equal in emphasis; therefore, the time spent on each should be equal as well. You would not want your first main point to be 30 seconds long, the second one to be 90 seconds, and the third 3 minutes. For example:

Specific Purpose: To explain to my classmates the rules of baseball.

- Baseball has rules about equipment.

- Baseball has rules about the numbers of players.

- Baseball has rules about play.

Main Point #2 isn’t really equal in size to the other two. There’s a great deal you could say about equipment and even more about the rules of playing baseball, but the number of players would take you about ten seconds to say. If Main Point #2 were “Baseball has rules about the positions on the field,” that would make more sense and be closer in level of importance to the other two.

Conclusion

The organization of your speech may not be the most interesting part to think about, but without it, great ideas will seem jumbled and confusing to your audience. Even more, good connectives will ensure your audience can follow you and understand the logical connections you’re making with your main ideas. Finally, because your audience will understand you better and perceive you as organized, you’ll gain more credibility as a speaker if you’re organized. A side benefit to learning to be an organized public speaker is that your writing skills will improve, specifically your organization and sentence structure.

Case study

Roberto is thinking about giving an informative speech on the status of HIV-AIDS currently in the U.S. He has different ideas about how to approach the speech. Here are his four main thoughts:

- pharmaceutical companies making drugs available in the developing world

- changes in attitudes toward HIV-AIDS and HIV-AIDS patients over the last three decades

- how HIV affects the body of a patient

- major breakthroughs in HIV-AIDS treatment

Assuming all these subjects would be researchable and appropriate for the audience, write specific purpose statements for each. What organizational patterns would he probably use for each specific purpose?

Media Attributions

- Speech Structure Flow © Mechele Leon is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Connectives

- https://blog-college.ku.edu/tag/study-abroad-stories/ ↵