Speechwriting

13 Presentation Aids

A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words

In this chapter . . .

Most public speeches given today are supplemented by presentation aids. While these can be useful in providing a visual element and helping clarify speech, if used poorly they can be more distracting. In this chapter we cover both technological presentation aids such as slide shows as well as other less conventional methods.

When you perform a speech, your audience members will experience your presentation through all five of their senses: hearing, vision, smell, taste, and touch. In some speaking situations, the speaker appeals only to the sense of hearing. But the speaking event can be greatly enriched by appeals to the other senses. This is the role of presentation aids.

Presentation aids are the resources beyond the speech words and delivery that a speaker uses to enhance the message conveyed to the audience. The type of presentation aids that speakers most typically make use of are visual aids: slideshows, pictures, diagrams, charts and graphs, maps, and the like. Audible aids include musical excerpts, audio speech excerpts, and sound effects. A speaker may also use fragrance samples or food samples as olfactory (sense of smell) or gustatory (sense of taste) aids. Finally, presentation aids can be three-dimensional objects, animals, and people.

When used correctly, presentation aids can significantly improve the quality of a speech performance.

Why Use Presentation Aids

Public speakers can deploy presentation aids for many useful reasons, including to highlight important points, clarify confusing details, amuse the audience, express emotions that are impossible to convey through words alone, and much more.

Presentation Aids Support Audience Understanding

As a speaker, your most basic goal is to help your audience understand your message. Presentation aids can reduce the possibility of misunderstanding. Presentation aids do this by clarifying or emphasizing what you are saying in your speech.

Clarification is important in a speech because if some of the information you convey is unclear, your listeners will come away puzzled or possibly even misled. Presentation aids can help clarify a message if the information is complex or if the point being made is a visual one.

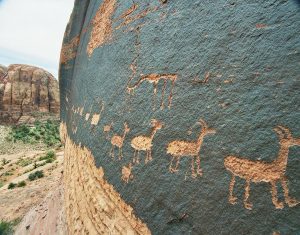

Clarifying is especially important when a speaker wants to help audience members understand a visual concept. For example, if a speaker is talking about the importance of petroglyphs in Native American culture, just describing the petroglyphs won’t completely help your audience to visualize what they look like. Instead, showing an example of a petroglyph, as in Figure 1.1 (“Petroglyph”) can more easily help your audience form a clear mental image of your intended meaning.

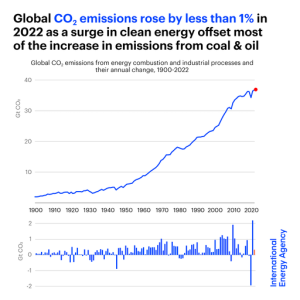

Another way presentation aids improve understanding is through emphasis. When you use a presentational aid for emphasis, you impress your listeners with the importance of an idea. In a speech on rising levels of CO2, you might show a chart. When you use a chart like the one in Figure 1.2 (“Global CO2 Emissions”) you give a pictorial emphasis on the changes in levels of CO2.

Presentation Aids Help Retention and Recall

Presentation aids can also increase the audience’s chances of remembering your speech. An image can serve as a memory aid to your listeners. Moreover, people remember information that is presented in sequential steps more easily than if that information is presented in an unorganized pattern. When you use a presentation aid to display the organization of your speech (such as can be done with PowerPoint slides), you’ll help your listeners to observe, follow, and remember the sequence of information you conveyed to them. This is why some instructors display a lecture outline for their students to follow during class and why a slide with a preview of your main points can be helpful as you move into the body of your speech.

Another advantage of using presentation aids is that they can boost your memory while you’re speaking. Using your presentation aids while you rehearse your speech will familiarize you with the association between a given place in your speech and the presentation aid that accompanies that material.

Presentation Aids Add Variety and Interest

Furthermore, presentation aids simply make your speech more interesting. For example, wouldn’t a speech on varieties of roses have greater impact if you accompanied your remarks with a picture of each rose? Similarly, if you were speaking to a group of gourmet cooks about Indian spices, you might want to provide tiny samples of spices that they could smell and taste during your speech.

Presentation Aids Enhance a Speaker’s Credibility

Even if you give a good speech, you run the risk of appearing unprofessional if your presentation aids are poorly executed. Conversely, a high-quality presentation will contribute to your professional image. This means that in addition to containing important information, your presentation aids must be clear, uncluttered, organized, and large enough for the audience to see and interpret correctly. Misspellings and poorly designed presentation aids can damage your credibility as a speaker. If you focus your efforts on producing presentation aids that contribute effectively to your meaning, that look professional, and that are managed well, your audience will appreciate your efforts and pay close attention to your message.

Types of Presentation Aids

Slideshow: When we think of public speaking presentation aids, our thoughts go first to a slideshow. Slide presentation software is the most common tool used by speakers to accompany their speeches. The most well-known one is PowerPoint, although there are several others like Prezi and Keynote. A slideshow is a presentation aid that is made up of slides that typically contain words, images, or a combination of both.

Video: A speaker may wish to show the audience a clip of a video or other moving image in their speech. This can be played stand-alone or incorporated into a slideshow.

Music or Sound: Similarly, sound and music can be used as a presentation aid, recorded or live. Similarly, a sound recording could be played stand-alone or incorporated into a slideshow.

Physical Objects: A speaker may bring in a model, or other physical object, as an aid to presentation. For example, if you were doing a speech about the importance of emotional support animals, you might bring in a dog.

People: It is possible to use a person as a presentation aid, as in the case of demonstrations.

Other Aids: Other “low-tech” presentation aids include printed handouts, whiteboards, and flipcharts.

The sections that follow will discuss each of these types in more depth.

Designing Slideshows

In many industries and businesses, there is an assumption that speakers will use presentation slideshows. They allow visualization of concepts, they are easily portable, and they can be embedded with videos and audio. You’ll probably be expected to have slide presentations in future assignments in college. Knowing how to use them, beyond the basic technology, is vital to being a proficient presenter.

But when do presentation slides become less effective? We have all sat through a presenter who committed the common error of putting far too much text on the slide. When a speaker does this, the audience is confused—do they read the text or listen to the speaker? An audience member can’t do both. Then, the speaker feels the need to read the slides rather than use PowerPoint for what it does best, visual reinforcement and clarification.

We have also seen many poorly designed PowerPoint slides, either through haste or lack of knowledge: slides where the graphics are distorted (elongated or squatty), words and graphics not balanced, text too small, words printed over photographs, garish or nauseating colors, or animated figures left up on the screen for too long and distracting the audience.

There are principles you can follow to create slides and slideshows that are effective. In addition to the rules below, Microsoft offers tips on best practices for PowerPoint slides.

Unity and Consistency

Generally, it’s best to use a single font for the text on your visuals so that they look like a unified set. Or you can use two different fonts in consistent ways, such as having all headings and titles in the same font and all bullet points in the same font. Additionally, the background should remain consistent.

Each slide should have one message, often only one photo or graphic. The audience members should know what they are supposed to look at on the slide.

Another area related to unity and consistency is the use of animation or movement. There are three types of animation in slideshows:

- little characters or icons that have movement. These may seem like fun, but they can be distracting.

- movement of text or objects on and off the screen. Although using this function takes up time when preparing your slides, it’s very useful. You can control what your audience sees. It also avoids bringing up all the text and material on a slide at one time.

- slide transitions, which is the design of how the next slide appears.

Emphasis, Focal Point, and Visibility

Several points should be made about how to make sure the audience sees what they need to see on the slides.

- make sure the information is large enough for the audience to see. Text being at least 22-point font is best for visibility.

- the standard rule for amount of text is that you should have no more than seven horizontal lines of text and the longest line should not exceed seven words.

- you should also avoid too many slides. Less sometimes really is more. Again, there is no fixed rule, but a ten-minute speech probably needs fewer than ten slides.

- Good contrast between the text and background is extremely important. Sans serif fonts such as Arial, Tahoma, and Verdana are better for reading from screens than serif fonts such as Times New Roman, or Garamond.

Tone

Fonts, color, clip art, photographs, and templates all contribute to tone, which is the attitude being conveyed in the slides. If you want a light tone, such as for a speech about cruises, some colors (springtime, pastel, cool, warm, or primary colors) and fonts (such as Comic Sans) and lots of photographs will be more appropriate. For a speech about the Holocaust, more somber colors and design elements would be more fitting, whereas clip art would not be.

Scale and Proportion

Although there are several ways to think about scale and proportion, we will discuss two here.

First, bullet points. Bullet points infer that the items in the bulleted list are equal, and the sequence doesn’t matter. If you want to communicate order, sequence, or priority, then use numbers. Bullet points should be short—not long, full sentences—but at the same time should be long enough to mean something. In a speech on spaying and neutering pets, the bullet point “pain” may be better replaced with “Pet feels little pain.”

Second, when you’re designing your slides, it’s best to choose a template and stick with it. If you input all your graphics and material and then change the template, the format of the slide will change, in some cases dramatically, and you’ll have distorted graphics and words covered up. You’ll then have to redesign each slide, which can be unnecessarily time-consuming.

Suitable Visual Images

Often, a speaker alternates text slides with slides containing visual images. Sometimes, a slideshow is made up entirely of images. Let’s look at the kinds of images you might use in a slideshow.

Charts: A chart is commonly defined as a graphical representation of data (often numerical) or a sketch representing an ordered process. Whether you create your charts or do research to find charts that already exist, it’s important for them to exactly match the specific purpose in your speech. Three common types of charts are statistical charts, sequence-of-steps chart, and decision trees.

Graphs: A graph is a pictorial representation of the relationships of quantitative data using dots, lines, bars, pie slices, and the like. Common graphs speakers utilize in their speeches include line graphs, bar graphs, pie graphs, and pictographs.

Diagrams: Diagrams are drawings or sketches that outline and explain the parts of an object, process, or phenomenon that can’t be readily seen.

Maps: Maps are extremely useful if the information is clear and limited. There are all kinds of maps, including population, weather, ocean current, political, and economic maps.

Photographs: and/or Drawings: Sometimes a photograph or a drawing is the best way to show an unfamiliar but important detail. Audiences expect high quality photographs, and as with all presentation aids, they should enhance the speech.

Using Video and/or Audio Recordings

Another particularly useful type of presentation aid is a video or audio recording. Whether it’s a short video from a website such as YouTube or Vimeo, a segment from a song, or a piece of a podcast, a well-chosen video or audio recording may be a good choice to enhance your speech.

There is one major warning to using audio and video clips during a speech: don’t forget that they are supposed to be aids to your speech, not the speech itself. Be sure to avoid these five mistakes that speakers often make when using audio and video clips:

- Avoid choosing clips that are too long for the overall length of the speech.

- Practice with the audio or video equipment prior to speaking. Fiddling around will not only take your audience out of your speech but also have a negative impact on your credibility. Be sure that the speakers on the computer are on and at the right volume level.

- Cue the clip to the appropriate place prior to beginning your speech.

- In addition to cueing up clip to the appropriate place, the browser window should be open and ready to go.

- The audience must be given context before a video or audio clip is played, specifically what the clip is and why it relates to the speech. At the same time, the video should not repeat what you have already said but add to it.

Objects or Models

Objects refer to anything you could hold up and talk about during your speech, as in Figure 1.3. If you’re talking about the importance of not using plastic water bottles, you might hold up a plastic water bottle and a stainless-steel water bottle as examples.

People

We can often use ourselves or other people to adequately demonstrate an idea during our speeches. If your speech is about ballroom dancing or ballet, you might use your body to demonstrate the basic moves in the cha-cha or the five basic ballet positions.

In some cases, such as for a demonstration speech, you might want to ask someone else to serve as your presentation aid. You should arrange ahead of time for a person (or persons) to be an effective aid—don’t assume that an audience member will volunteer on the spot. The transaction between you and your human presentation aid must be appropriate, especially if you’re going to demonstrate something like a dance step. In short, make sure your helper will know what is expected of them and consents to it.

Other Types of Presentation Aids

Dry-Erase Board

Numerous speakers utilize dry-erase boards effectively. Typically, these speakers use the dry-erase board for interactive components of a speech. For example, maybe you’re giving a speech in front of a group of executives. You may have a PowerPoint all prepared, but at various points in your speech you want to get your audience’s responses.

If you ever use a chalk or dry-erase board, follow these four simple rules:

- Write large enough so that everyone in the room can see.

- Print legibly; don’t write in cursive script.

- Write short phrases; don’t take time to write complete sentences.

- Be sure you have markers that will not go dry; clean the board afterward.

Flipchart

A flipchart is useful for situations when you want to save what you have written for future reference or to distribute to the audience after the presentation. As with whiteboards, you’ll need good markers and readable handwriting, as well as a strong easel to keep the flipchart upright.

Handouts

Handouts are appropriate for delivering information that audience members can take away with them.

- make sure the handout is worth the trouble of making, copying, and distributing it. Does the audience really need the handout?

- make sure to bring enough copies of the handout for each audience member to get one.

- Stay away from providing a single copy of a handout to pass around. It’s distracting and everyone will see it at different times in the speech, which is also true about passing any object around the room.

- If you have access to the room ahead of time, place a copy of the handout at or on each seat in the audience. If the handout is a “takeaway,” leave it on a table near the door so that those audience members who are interested can take one on their way out.

How to Perform with Presentation Aids

Just as everything else in public speaking performance, it takes practice to effectively perform a speech while seamlessly incorporating presentation aids. Below are some tips and tricks for how to include presentation aids as part of a strong speech delivery.

Speaking with a Slide Presentation

The rhythm of your slide presentation should be reasonably consistent—you would not want to display a dozen different slides in the first minute of a five-minute presentation and then display only one slide per minute for the rest of the speech.

Whether using a remote “clicker” or the attached mouse, you should connect what is on the screen to what you’re talking about at the moment. Put reminders in your notes about when you need to change slides during your speech.

A basic presentation rule is to only show your visual aid when you’re talking about it and remove it when you no longer are talking about it. If you’re using PowerPoint and if you’re not talking about something on a slide, put a black slide between slides in the presentation so that you have a blank screen for parts of the speech.

Some other practical considerations are as follows:

- Be sure the file is saved in a format that will be “readable” on the computer where you’re presenting.

- Any borrowed graphic must be cited on the slide where it’s used; the same would be true of borrowed textual material. Putting your sources only on the last slide is insufficient.

- A strong temptation for speakers is to look at the projected image rather than the audience during the speech. This practice cuts down on eye contact, of course, and is distracting for the audience. Two solutions for that are to print your notes from the presentation slides and/or use the slides as your note structure. Also remember that if the image is on the computer monitor in front of you, it’s on the screen behind you.

- Always remember—and this can’t be emphasized enough—technology works for you, not you for the technology. The presentation aids are aids, not the speech itself.

- As mentioned before, sometimes life happens—technology does not work. It could be that the projector bulb goes out or the Internet connection is down. The show must go on.

- If you’re using a video or audio clip from an Internet source, it’s probably best to hyperlink the URL on one of the slides rather than minimize the program and change to the Internet site.

- Finally, it’s common for speakers to think “the slide changes, so the audience know there is a change, so I don’t need a verbal transition.” Please don’t fall into this trap. Verbal transitions are just as, and maybe more, necessary for a speech using slides.

Other Tips

- Do not obscure your visual aid– practice standing to the side of your aid when rehearsing.

- Remember to keep eye contact with the audience, even when referring to a visual aid. Certainly, never turn your back on the audience!

- Rehearse with your visual aids. You want to have transitions between showing and hiding visual aids to be seamless, with as little filler time or distractions as possible. Practice makes perfect in this regard.

- As will be mentioned again below: simplicity is key. Avoid anything too distracting, too complicated, anything that will take a lot of time away from your speech content. You always want aids to supplement, not supplant, your speech content and delivery.

Avoiding Problems with Presentation Aids

Presentation aids can be tricky to use, as they can easily distract from the focus of your speech: the content and your delivery. One tip to keep in mind is to use only as many presentation aids as necessary to present your message or to fulfill your classroom assignment. The number and the technical sophistication of your presentation aids should never overshadow your speech.

Another important consideration is technology. Keep your presentation aids within the limits of the working technology available to you. As the speaker, you’re responsible for arranging the things you need to make your presentation aids work as intended. Test the computer and projector setup. Have your slides on a flash drive AND send it to yourself as an attachment or upload to a Cloud service. Have an alternative plan prepared in case there is some glitch that prevents your computer-based presentation aids from being usable. And of course, you must know how to use the technology.

More important than the method of delivery is the audience’s ability to see and understand the presentation aid. It must deliver clear information, and it must not distract from the message. Avoid overly elaborate or confusing presentation aids. Instead, simplify as much as possible, emphasizing the information you want your audience to understand. Remember the acronym KISS: Keep it Simple, Speaker!

Another thing to remember is that presentation aids don’t “speak for themselves.” When you display a visual aid, you should explain what it shows, pointing out and naming the most important features.

Conclusion

To finish this chapter, we will recap and remind you about the principles of effective presentation aids. Whether your aid is a slide show, object, a person, or dry erase board, these standards are essential:

- Presentation aids must be easily seen or heard by your audience.

- Presentation aids must be portable, easily handled, and efficient.

- Presentation aids should disappear when not in use.

- Presentation aids should be aesthetically pleasing, which includes in good taste. Avoid shock value just for shock value.

Media Attributions

- Petroglyphs © Jim Bouldin is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Rise in Global CO2 Emissions, 2022 © International Energy Agency is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Speech with Prop © Ralf Rebmann is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license