Verbal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Understand the relationship between communication and symbols.

- Describe how words and meanings are socially constructed.

- Recognize the different functions of language in everyday interpersonal interactions, including both benefits and negative outcomes.

Have you ever said something that someone else misinterpreted as something else? Some of the most common problems in interpersonal communication stem from the use of language. For instance, two students, Kelly and James, are texting each other. Kelly texts James about meeting for dinner, and James texts “K” instead of “okay.” Kelly is worried because she thinks James is mad. She wonders why he texted “K” instead of “k,” “ok,” “yes” or “okay.” James was in a hurry, and he just texted in caps because he was excited to see Kelly.

This example gives us an understanding of how language can influence how our perceptions. Kelly and James had two different perceptions of the same event. One person was worried, and the other person was excited. This chapter examines verbal communication, embracing the idea that words are powerful. The words that we use can impact how other people perceive us and how to perceive others.

Language is a system of human communication using a particular form of spoken or written words or other symbols. Language consists of the use of words in a structured way. Language helps us understand others’ wants, needs, and desires. Language can help create connections, but it can also pull us apart. Language is vital to communication. Without language, it is very difficult to develop meaningful connections with others? Language allows us to express ourselves and obtain our goals.

Language can often be the most element in human communication. Language is made up of words, which are arbitrary symbols. In this chapter, we will learn about how words work, the functions of language, and how to improve verbal communication.

Linking Communication and Symbols

Communication Is Symbolic

Have you ever noticed that we can hear or look at something like the word “cat” and immediately know what those three letters mean? From the moment you enter grade school, you are taught how to recognize sequences of letters that form words that help us understand the world. With these words, we can create sentences, paragraphs, and books like this one. The letters used to create the word “cat” and then the word itself is what communication scholars call symbols. A symbol is a mark, object, or sign that represents something else by association, resemblance, or convention.

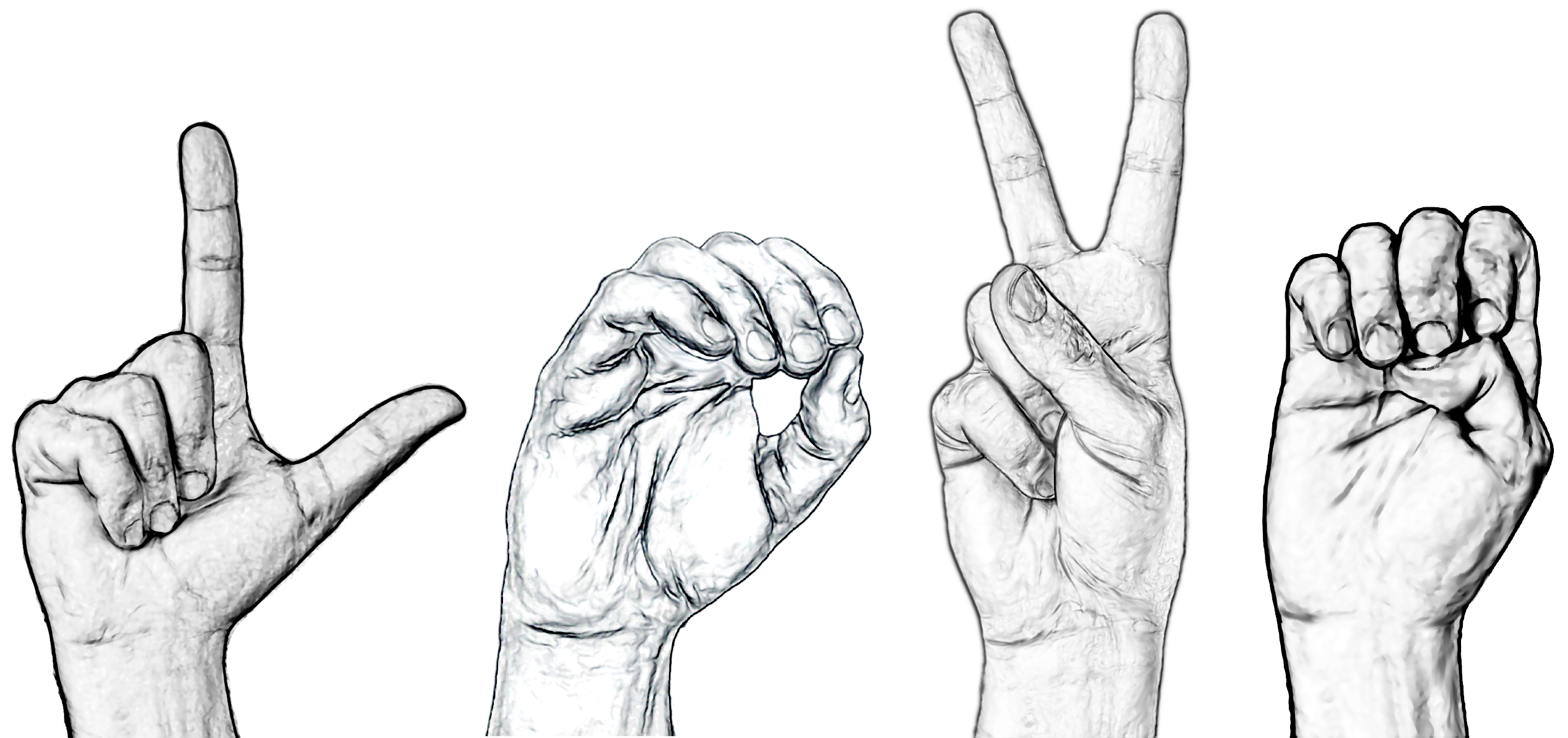

Consider a word you’re probably familiar with: love. The four letters that make of the word “l,” “o,” “v,” and “e,” are visual symbols that, when combined, form the word “love,” which is a symbol associated with intense regard or liking. For example, I can “love” chocolate. However, the same four-letter word has other meanings attached to it as well. For example, “love” can represent a deeply intimate relationship or a romantic/sexual attachment. In the first case, we could love our parents/guardians and friends, but in the second case, we experience love as a factor of a deep romantic/sexual relationship. So these are just three associations we have with the same symbol, love. Figure 1 depicts American Sign Language (ASL) letters for the word “love.” In this case, the hands themselves represent symbols for English letters, which is an agreed upon convention of users of ASL to represent “love.”

Symbols can also be visual representations of ideas and concepts. For example, look at the various symbols in Figure 2 of various social media icons. In this image, you see symbols for a range of different social media sites, including Facebook (lowercase “f”), Twitter (the bird), Snap Chat (the ghost image), and many others. Admittedly, the icons for YouTube and dig just use their names, but these images have become associated with these online platforms over many years.

The Symbol is Not the Thing

Now that we’ve explained what symbols are, we should probably offer a few very important guides. First, the symbol is not the thing that it is representing. For example, the word “dog” is not a member of the canine family that greets you when you come home every night. Similarly, if you explore the symbols in Figure 2 these symbols are not the organizations themselves. The stylized red P is not Pinterest, the lowercase blue f is not Facebook. Each of these might best be described as computer code that exists on the World Wide Web that allows us, people, to interact, but you can recognize the symbol associated with these businesses and this code.

Symbols are Arbitrary

How we assign symbols is entirely arbitrary. For example, in Figure 3, we see two animals that are categorized under the symbols “dog” and “cat.” In this image, the “dog” is on the left side, and the “cat” is on the right side. The words we associate with these animals only exist because we have said it’s so for many, many years. Back when humans were labeling these animals, we could just have easily called the one on the left “cat” and the one on the right “dog,” but we didn’t. If we called the animal on the left “cat,” would that change the nature of what that animal is? Not really. The only thing that would change is the symbol we have associated with that animal.

Let’s look at another symbolic example you are probably familiar with – :). The “smiley” face or the two pieces of punctuation (colon followed by closed parentheses). This symbol may seem like it’s everywhere today, but it’s only existed since September 1982. Today we have many symbolic emoticons to choose from: 🤔👀🏾🤚🏾.

Communication Is Shared Meaning

Although the assignment of symbols to real things and ideas is arbitrary, our understanding of them exists because we agree to their meaning. If we were talking and I said, “it’s time for tea,” you may think that I’m going to put on some boiling water and pull out the oolong tea. However, if I said, “it’s time for tea” in the United Kingdom, you would assume that we were getting ready for our evening meal. Same word, but two very different meanings depending on the culture one uses the term. In the United Kingdom, high tea (or meat tea) is the evening meal. Dinner, on the other hand, would represent the large meal of the day, which is usually eaten in the middle of the day. Of course, in the United States, we refer to the middle of the day meal as lunch and often refer to the evening meal as dinner (or supper).

Let’s imagine that you were recently at a party. Two of your friends had recently attended the same Broadway play together. You ask them “how the play was,” and here’s how they responded:

So, we got to the theatre 20 minutes early to ensure we were able to get comfortable and could do some people watching before the show started. The person sitting in front of us had the worst comb-over I had ever seen. Half through Act 1, the hair was flopping back in our laps like the legs of a spider. I mean, those strands of hair had to be 8 to 9 inches long and came down on us like it was pleading with us to rescue it. Oh, and this one woman who was sitting to our right was wearing this huge fur hat-turban thing on her head. It looked like some kind of furry animal crawled up on her head and died. I felt horrible for the poor guy that was sitting behind her because I’m sure he couldn’t see anything over or around that thing.

Here’s is how your second friend described the experience:

I thought the play was good enough. It had some guy from the UK who tried to have a Brooklyn accent that came in and out. The set was pretty cool though. At one point, the set turned from a boring looking office building into a giant tree. That was pretty darn cool. As for the overall story, it was good, I guess. The show just wasn’t something I would normally see.

In this case, you have the same experience described by two different people. We are only talking about the experience each person had in an abstract sense. In both cases, you had friends reporting on the same experience but from their perceptions of the experience. With your first friend, you learn more about what was going on around your friend in the theatre but not about the show itself. The second friend provided you with more details about her perception of the play, the acting, the scenery, and the story. Did we learn anything about the content of the “play” through either conversation? Not really.

Many of our conversations resemble this type of experience recall. In both cases, we have two individuals who are attempting to share with us through communication specific ideas and meanings. However, sharing meaning is not always very easy. In both cases, you asked your friends, “how the play was.” In the first case, your friend interpreted this phrase as being asked about their experience at the theatre itself. In the second case, your friend interpreted your phrase as being a request for her opinion or critique of the play. As you can see in this example, it’s very easy to get very different responses based on how people interpret what you are asking.

Communication scholars often say that “meanings aren’t in words, they’re in people” because of this issue related to interpretation. Yes, there are dictionary definitions of words. Earlier in this chapter, we provided three different dictionary-type definitions for the word “love:” 1) intense regard or liking, 2) a deeply intimate relationship, or 3) a romantic/sexual attachment. These types of definitions we often call denotative definitions. However, it’s also important to understand that in addition to denotative definitions, there are also connotative definitions, or the emotions or associations a person makes when exposed to a symbol. For example, how one personally understands or experiences the word “love” is connotative. The warm feeling you get, the memories of experiencing love all come together to give you a general, personalized understanding of the word itself. One of the biggest problems that occur is when one person’s denotative meaning conflicts with another person’s connotative meaning. For example, when I write the word “dog,” many of you think of four-legged furry family members. If you’ve never been a dog owner, you may just generally think about these animals as members of the canine family. If, however, you’ve had a bad experience with a dog in the past, you may have very negative feelings that could lead you to feel anxious or experience dread when you hear the word “dog.” As another example, think about clowns. Some people see clowns as cheery characters associated with the circus and birthday parties. Other people are genuinely terrified by clowns. Both the dog and clown cases illustrate how we can have symbols that have different meanings to different people.

Relating Words and Meaning

One person might call a shopping cart a buggy, and another person might call it a cart. There are several ways to say you would like a beverage, such as, “liquid refresher,” “soda,” “Coke,” “pop,” “refreshment,” or “drink.” A pacifier for a baby is sometimes called a “paci,” “binkie,” “sookie,” or “mute button.” Linguist Robin Tolmach Lakoff asks, “How can something that is physically just puffs of air, a mere stand-in for reality, have the power to change us and our world?”1 This example illustrates that meanings are in people, and words don’t necessarily represent what they mean.

Words can have different rules to help us understand the meaning. There are three rules: semantic, syntactic, and pragmatic.2

Semantic Rules

First, semantic rules are the dictionary definition of the word. Semantic rules are definitional meanings associated with words. However, the meaning can also change based on the context in which it is used. For instance, the word fly by itself does not mean anything. It makes more sense if we put the word into a context by saying things like, “There is a fly on the wall;” “I will fly to Chicago tomorrow;” “That girl is so fly;” or “The fly on your pants is open!” We would not be able to communicate with others if we did not have semantic rules.

Syntactic Rules

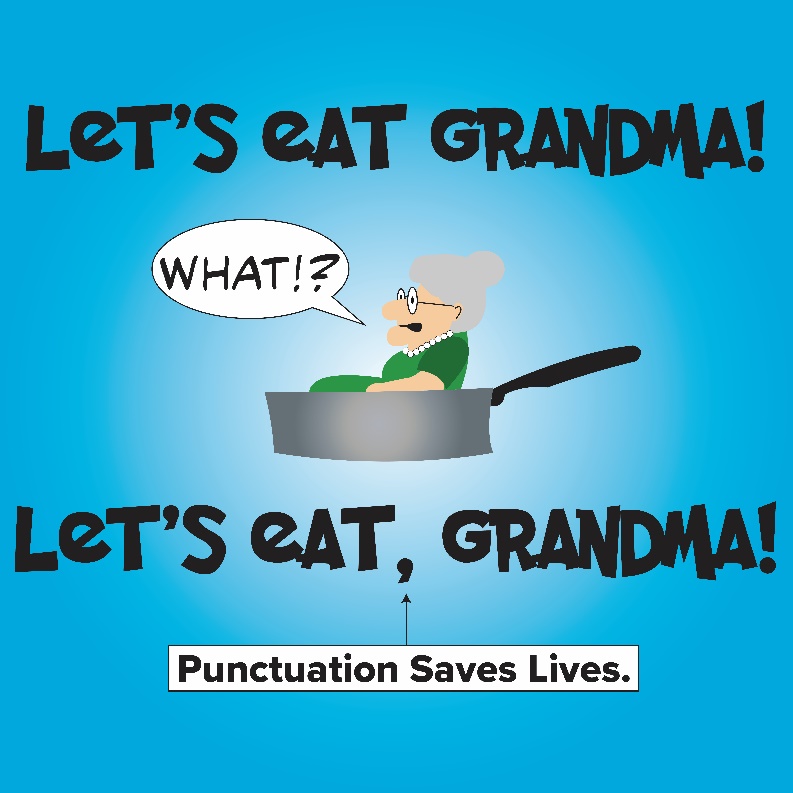

Second, syntactic rules govern how we help guide the words we use. Syntactic rules can refer to the use of grammar, structure, and punctuation to help effectively convey our ideas. For instance, we can say “Where are you” as opposed to “where you are,” which can convey a different meaning and have different perceptions. The same thing can happen when you don’t place a comma in the right place. The comma can make a big difference in how people understand a message.

A great example of how syntactic rules is the Star Wars character, Yoda, who often speaks with different rules. He has said, “Named must be your fear before banish it you can” and “Happens to every guy sometimes this does.” This example illustrates that syntactic rules can vary based on culture or background.

Another example is Figure 4. In this case, we learn the importance that a comma can make in written in language. In the first instance, “Let’s eat grandma!” is quite different than the second one, “Let’s eat, grandma!” The first implies cannibalism and the second a family dinner. As the image says, punctuation saves lives.

Pragmatic Rules

Third, pragmatic rules help us interpret messages by analyzing the interaction completely. We need to consider the words used, how they are stated, our relationship with the speaker, and the objectives of our communication. For instance, the words “I want to see you now” would mean different things if the speaker was your boss versus your romantic partner. One could be a positive connotation, and another might be a negative one. The same holds true for humor. If we know that the other person understands and appreciates sarcasm, we might be more likely to engage in that behavior and perceive it differently from someone who takes every word literally.

Most pragmatic rules are based on culture and experience. For instance, the term “Netflix and chill” often means that two people will hook up. Imagine someone from a different country who did not know what this meant; they would be shocked if they thought they were going to watch Netflix with the other person and just relax. Another example would be “Want to have a drink?”, which usually infers an alcoholic beverage. Another way of saying this might be to say, “Would you like something to drink?” The second sentence does not imply that the drink has to contain alcohol.

It is common for people to text in capital letters when they are angry or excited. You would interpret the text differently if the text was not in capital letters. For instance, “I love you” might be perceived differently from “I LOVE YOU!!!” Thus, when communicating with others, you should also realize that pragmatic rules can impact the message.

Words Create Reality

Language helps to create reality. Often, humans will label their experiences. For instance, the word “success” has different interpretations depending on your perceptions. Success to you might be a certain type of car or a certain amount of income. However, for someone else, success might be the freedom to do what they love or to travel to exotic places. Success might mean something different based on your background or your culture.

If a child complains that they don’t feel loved, but the parents/guardians argue that they continuously show affection by giving hugs and doing fun shared activities, who would you believe? The child might say that they never heard their parents/guardians say the word love, and hence, they don’t feel love. Though the parents/guardians and children are each talking about ‘love’ the way that meaning is conveyed, verbally and nonverbally, effect how each views reality.

Specific words can make a difference in how a person will receive the message. That is why leaders (and politicians) may spend time looking for the right word to capture the true essence of a message. A personal trainer might be careful to use the word “overweight” as opposed to “fat,” because the two sound drastically different. At Disney world, they call their employees “cast members” rather than workers, because it gives a perception that each person has a part in helping to run the show. Even on a resume, you might select words that set you apart from the other applicants. For instance, if you were a cook, you might say “culinary artist.” It gives the impression that you weren’t just cooking food, you were making masterpieces with food. Words matter, and how they are used will make a difference.

Words Reflect Attitudes

When we first fall in love with someone, we will use positive adjectives to describe that person. However, if you have fallen out of love with that person, you might use negative or neutral words to describe that same person. Words can reflect attitudes. Some people can label one experience as pleasant and another person can have the opposite experience. This difference is because words reflect our attitudes about things. If a person has positive emotions towards another, they might say that that person is funny, mature, and thrifty. However, if the person has negative feelings or attitudes towards that same person, they might describe them has childish, old, and cheap. These words can give a connotation about how the person perceives them.

Level of Abstraction

When we think of language, it can be pretty abstract. For example, when we say something is “interesting,” it can be positive or negative. That is what we mean when we say that language is abstract. Language can be very specific. You can tell someone specific things to help them better understand what you are trying to say by using specific and concrete examples. For instance, if you say, “You are a jerk!”, the person who receives that message might get pretty angry and wonder why you said that statement. To be clear, it might be better to say something like, “When you slammed that door in my face this morning, it really upset me, and I didn’t think that behavior was appropriate.” The second statement is more descriptive.

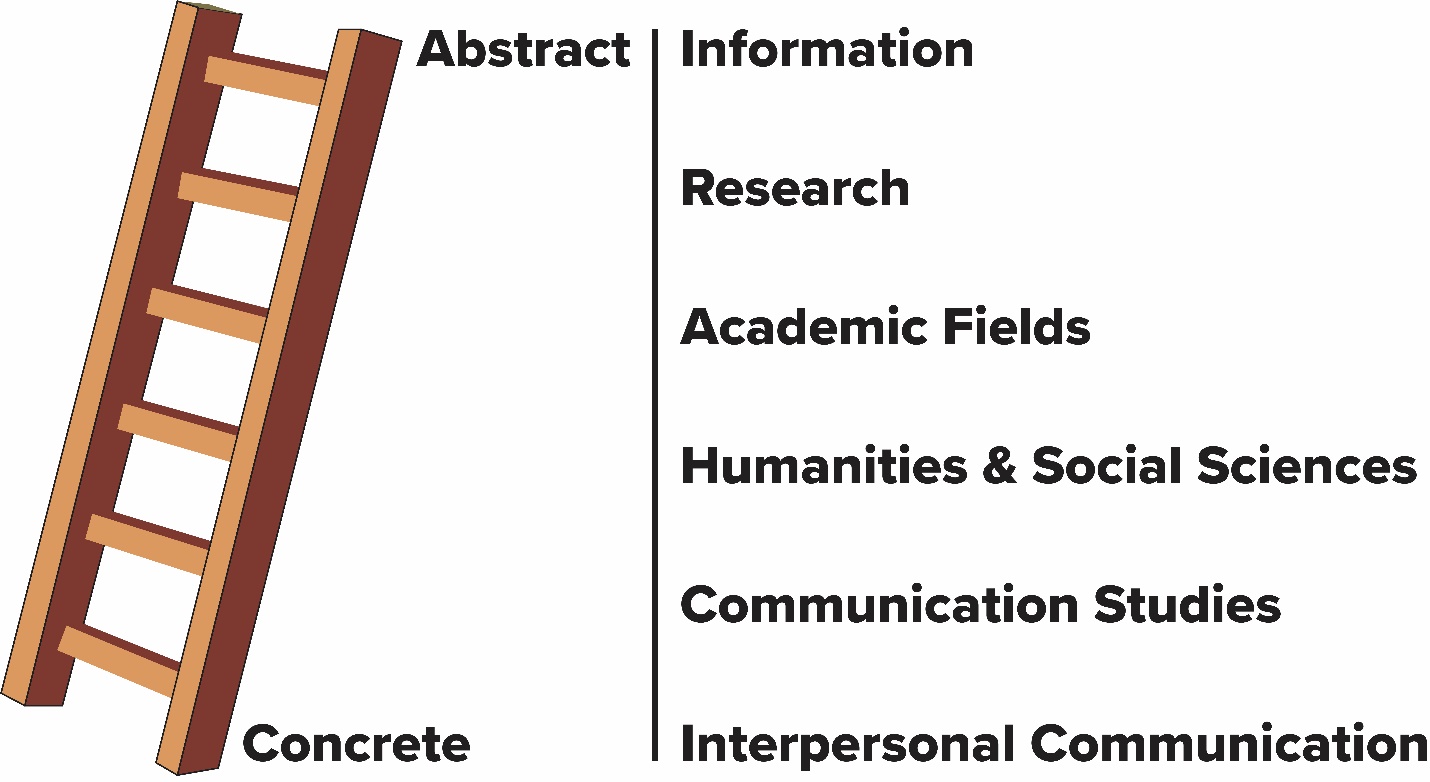

In 1941, linguist S.I. Hayakawa created what is called the abstraction ladder (Figure 5).3 The abstraction ladder starts abstract at the top, while the bottom rung and is very concrete. Figure 5 shows how you can go from abstract ideas (e.g., information) through various levels of more concrete ideas down to the most concrete idea (e.g., interpersonal communication). Ideally, you can see that as we move down the ladder, the topic becomes more fine-tuned and concrete.

In our daily lives, we tend to use high levels of abstraction all the time. For instance, growing up, your parents/guardians probably helped you with homework, cleaning, cooking, and transporting you from one event to another. Yet, we don’t typically say thank you to everything; we might make a general comment, such as a thank you rather than saying, “Thank you so much for helping me with my math homework and helping me figure out how to solve for the volume of spheres.” It takes too long to say that, so people tend to be abstract. However, abstraction can cause problems if you don’t provide enough description.

Metamessages

Metacommunication is communication about communication.4 It’s an abstraction of what we feel we’re talking about, as show in Figure 6. Metamessages are relationship messages that are sent among people who they communicate. These messages can be verbal, nonverbal, direct, or indirect. For instance, if you see two friends just talking about what they did last weekend, they are also sending metamessages as they talk. Metamessages can convey affection, appreciation, disgust, ridicule, scorn, or contempt. Every time you send messages to others, notice the metamessages that they might be sending you. Do they seem upset or annoyed with certain things that you say? In this book, we encourage you to consider your own messages, it’s possible you may not realize what metamessages you are sending out to others.

Words and Meanings

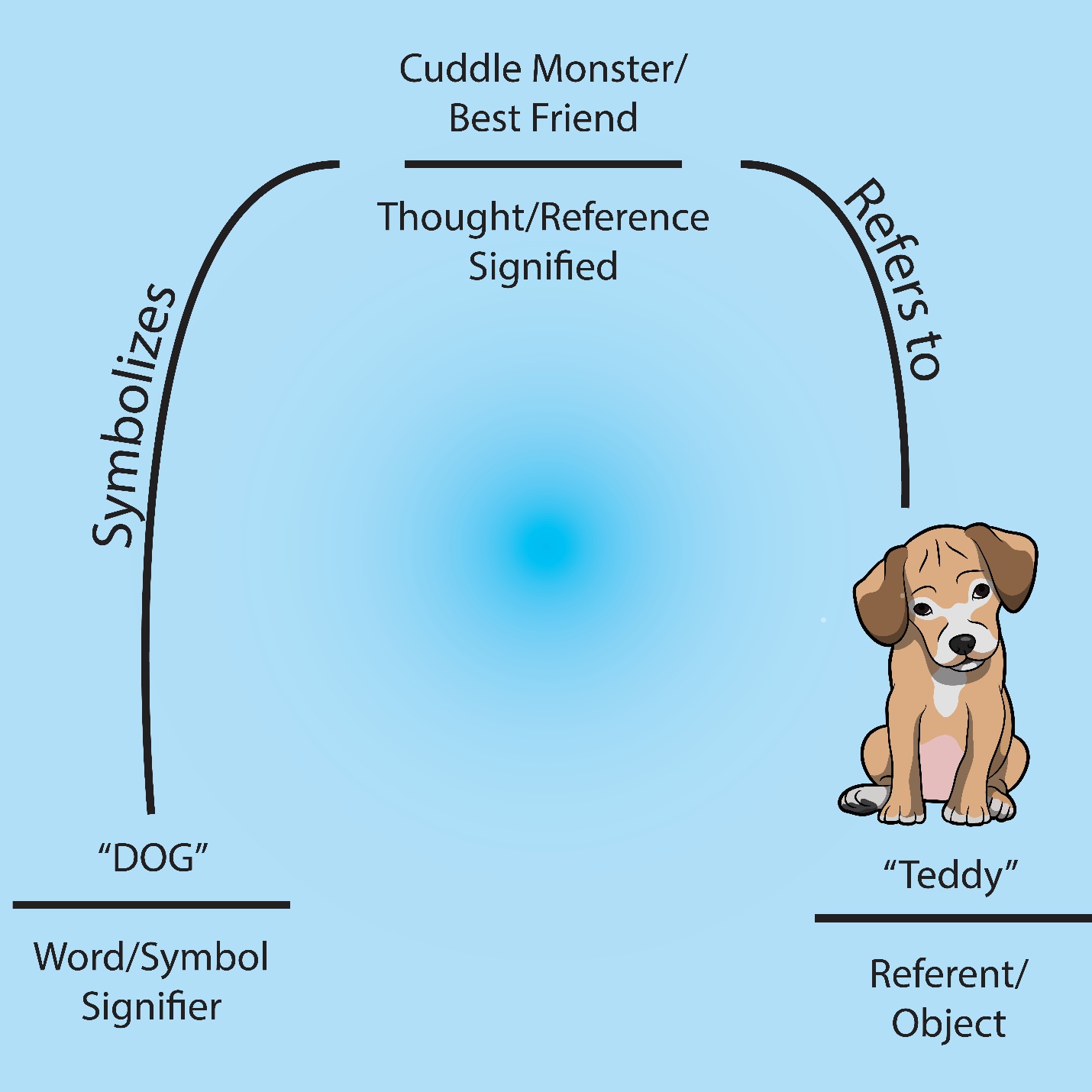

Words can have denotative meanings or connotative meanings. In this section, we will learn about the differences and the triangle of meaning.5 Ogden and Richards noticed that misunderstandings occur when people associate different meanings with the same message. Their model (Figure 7) illustrates that there is an indirect association between a word and the actual referent or thing it represents.

As you can see, when you hear the word “dog,” it conjures up meaning for different people. The word “dog” itself is a symbol and signifier, or sound elements or other linguistic symbols that represents an underlying concept or meaning. When we hear the word “dog,” it is what we call the “signified,” or the meaning or idea expressed when someone hears the word. In this case, maybe you have a dog, and you really see that dog as your best friend, or maybe you call him your little “cuddle monster” because he always wants to be connected to you at all times. Again, meaning that we attach to the symbol is still separate from the physical entity itself. In this case, there is a real dog named Teddy, who is the referent, or the physical thing that a word or phrase denotes or stands for.

Words can have a denotative meaning, which is the dictionary definition. These are words that most people are familiar with, and they all can agree on the understanding of that word. If you asked a person what a car or a phone is, they would most likely know what you are talking about when you use those words.

Words can also have a connotative meaning, which is a subjective definition of the word. The word might mean something different from what you meant. For example, you may hear someone referring to their baby. You could fairly safely assume that the person is referring to their infant, but just as easily they could be referring to a significant other.

Functions of Language

Based on research examining how children learn language, it was found that children are trying to create “meaning potential.”6 In other words, children learn language so they can understand and be understood by others. As children age, language serves different functions.

Instrumental and Regulatory Functions

Children will typically communicate in a fashion that lets parents/guardians know what they want to do. When children are born, parents/guardians have to figure out if the child is hungry, thirsty, dirty, or sick. Later, when the child acquires language, the child can let the parent/guardian know what they want by using simple words like “eat” or “drink.”

Instrumental functions use language to fulfill a need. For us to meet our needs, we need to use language that other people understand. Think about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which we previously covered–“Mom, I’m hungry!” “Ouch that hurt!” “I could use a drink.” “Hold my hand.” The way we talk often meets instrumental, or need-based functions.

Regulatory functions of language are to influence the behaviors of others through requests, rules, or persuasion. These functions may coincide with out needs, but they do not always. For example, you might say “go this way” or “be kind to your brother.” Regulatory functions are also present in advertisements that tell us to eat healthier or exercise more using specific products.

Interactional and Imaginative Functions

Interactional functions of language are used to help maintain or develop the relationship. Interactional functions also help to alleviate the interaction. Examples might include “Thank you,” “Please,” or “I care about you.”

Imaginative functions of language help to create imaginary constructs and tell stories. This use of fantasy usually occurs in play or leisure activities. People who roleplay in video games will sometimes engage in imaginative functions to help their character be more effective and persuasive.

Personal Functions

Personal functions, or the use of language to help you form your identity or sense of self. In job interviews, people are asked, “how do you describe yourself?” For some people, this is a challenging question because it showcases what makes you who you are. The words you pick, as opposed to others, can help define who you are.

Perhaps someone told you that you were funny. You never realized that you were funny until that person told you. Because they used the word “funny” as opposed to “silly” or “crazy,” it caused you to have perceptions about yourself. This example illustrates how words serve as a personal function for us. Personal functions of language are used to express identity, feelings, and options.

Heuristic and Representational Functions

The heuristic function of language is used to learn, discover, and explore. The heuristic function could include asking several questions during a lecture or adding commentary to a child’s behavior. Another example might be “What is that tractor doing?” or “why is the cat sleeping?”

Representational functions of language are used to request or relay information. These statements are straightforward. They do not seek for an explanation. For instance, “my cat is asleep” or “the kitchen light isn’t working.”

Cultural Functions and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

We know a lot about a culture based on the language that the members of the group speak.7 Some words exist in other languages, but we do not have them in English. For instance, in China, there are five different words for shame, but in the English language, we only have one word for shame. Anthropologist Franz Boas studied the Inuit people of Baffin Island, Canada, in the late 1800s and noted that they had many different words for “snow.” In fact, it’s become a myth over the years that the Inuit have 50 different words for snow. In reality, as Laura Kelly points out, there are a number of Inuit languages, so this myth is problematic because it attempts to generalize to all of them.8

Analyzing the Hopi Native American language, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf discovered that there is not a difference between nouns and verbs.9 To the Hopi people, their language showcases how their world and perceptions of the world are always in constant flux. The Hopi believe that everything is evolving and changing. Their conceptualization of the world is that there is continuous time. As Whorf wrote, “After a long and careful analysis the Hopi language is seen to contain no words, grammatical forms, construction or expressions that refer directly to what we call ‘time’, or to past, present or future.”10

A very popular theory that helps us understand how culture and language coexist is the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.11 This hypothesis helps us understand cultural differences in language use. The theory suggests that language impacts perceptions by showing a culture’s worldview. The hypothesis is also seen as linguistic determinism, which is the perspective that language influences our thoughts.

Linguistic relativity provides more room for the role of experience and understanding than linguistic determinism. Linguistic relativity argues that the structure of a language influences its speakers’ worldview or cognition, and thus individuals’ languages determine or influence their perceptions of the world. Language can express not only our thoughts but our feelings as well. Language not only represents things, but also how we feel about things. For instance, in the United States, most houses will have backyards. In Japan, due to limited space, most houses do not have backyards, and thus, it is not represented in their language. Many Japanese people do not understand the concept of a backyard, and they don’t have a word for a backyard. All in all, language helps to describe our world and how we understand our world.

The Importance of Language

By now, you can see that language influences how we make sense of the world. In this section, we will understand some of the ways that language can impact our perceptions and possibly our behavior. To be effective communicators, we need to realize the different ways that language can be significant and instrumental.

Naming and Identity

New parents/guardians typically spend a great deal of time trying to pick just the right name for their newborn. Some names are very distinctive, which also makes them memorable and recognizable. Think about musical artists or celebrities with unique names. It helps you remember them, and it helps you distinguish that person from others. Some names encompass some cultural or ethnic identity. In the popular book, Freakonomics, the authors showed a relationship between names and socioeconomic status.15 They discover that a popular name usually starts with high socioeconomic families, and then it becomes popular with lower socioeconomic families. Hence, it is very conceivable to determine the socioeconomic status of people you associate with based on their birth date and name. Figure 8 shows some of the more popular baby names for girls and boys, along with names that are non-binary.

Affiliation

When we want others to associate with us or have an affiliation with us, we might change the way we speak and the words we use. All of those things can impact how other people relate to us. Researchers found that when potential romantic partners employed the same word choices regarding pronouns and prepositions, then interest also increased. At the same time, couples that used similar word choices when texting each other significantly increased their relationship duration.16 This study implies that we often inadvertently mimic other people’s use of language when we focus on what they say.

If you have been in a romantic relationship for a long period, you might create special expressions or jargon for the other person, and that specialized vocabulary can create greater closeness and understanding. The same line of thinking occurs for groups in a gang or persons in the military. If we adapt to the other person’s communication style or converge, then we can also impact perceptions of affiliation. Research has shown that people who have similar speech also have more positive feelings for each other.17 However, speech can also work in the opposite direction when we diverge, or when we communicate in a very different fashion. For instance, a group from another culture might speak the same dialect, even though they can speak English, in order to create distance and privacy from others.

Types of Language

Formal vs. Informal Language

In everyday conversation across situations you will probably notice that there is a difference in language use based on the environment, who you are talking to, and the reason for communicating. This is commonly called code-switching. Put simply, you talk differently to your best friend than you do your boss or a grandparent. In this section, we will discuss the different types of language. The types of language used will impact how others view you and if they will view you positively or negatively.

How you compose a text to your best friend is going to use different grammatical structures and words than when you compose an email to your professor. One of the main reasons for this difference is because of formal and informal language. Table 1 provides a general overview of the major differences between formal and informal language.

| Formal Language | Informal Language |

|---|---|

| Used in carefully edited communication. | Used in impromptu, conversational communication. |

| Used in academic or official content. | Used in everyday communication. |

| The sentence structure is long and complicated. | The sentence structure is short, choppy, and improvised. |

| The emphasis is on grammatical correctness. | The emphasis is on easily understood messages using everyday phrases. |

| Uses the passive voice. | Uses the active voice. |

| Often communicated from a detached, third person perspective. | Perspective is less of a problem (1st, 2nd or 3rd). |

| Speakers/writers avoid the use of contractions. | Speakers/writers can actively include contractions. |

| Avoid the inclusion of emotionally laden ideas and words. | It allows for the inclusion of emotions and empathy. |

| Language should be objective. | Language can be subjective. |

| Language should avoid the use of colloquialisms. | It’s perfectly appropriate to use colloquialisms. |

| Only use an acronym after it has clearly been spelled out once. | People use acronyms without always clearly spelling out what it means. |

| All sentences should be complete (clear subjects and verbs). | Sentences may be incomplete (lacking a clear subject and/or verb). |

| The use of pronouns should be avoided. | The use of personal pronouns is common. |

| Avoids artistic languages as much as possible. | Includes a range of artistic language choices (e.g., alliteration, anaphora, hyperbole, onomatopoeia, etc.). |

| Arguments are supported by facts and documented research. | Arguments are supported by personal beliefs and opinions. |

| Language is gender neutral. | Language includes gender references. |

| Avoids the imperative voice. | Uses the imperative voice. |

Table 1 Formal vs. Informal Language

Formal Language

When applying for a job, you will most likely use formal language in your cover letter and resume. Formal language is official and academic language. You want to appear intelligent and capable, so formal language helps you accomplish those goals. Formal language often occurs when we write. Formal language uses full sentences and is grammatically correct. Formal language is more objective and more complex. Most legal agreements are written in formal language.

Informal Language

Informal language is common, everyday language, which might include slang words. It is continuous and casual. We use informal language when we talk to other people. It is more simple. Informal language tends to use more contractions and abbreviations. If you look at your text messages, you will probably see several examples of informal language.

Jargon

Jargon is the specialized or technical language of a specific group or profession that may not be understood by outsiders.23 If you are really into cars or computers, you probably know a lot about the different parts and functions. Jargon is normally used in a specific context and may be understood outside that context. Jargon consists of a specific vocabulary that uses words that only certain people understand. The business world is full of jargon. A 2023 survey provides some of the most common business jargon:24

- Actionable

- Best practices

- Buzzworthy

- Dialogue

- Move the needle

- Raise the bar

- ROI (return on investments)

- Top of mind

- Viral

Perhaps you’ve heard a few of these jargon phrases in your workplace, or others like ‘low hanging fruit’ or ‘circle back.’ Maybe you have even found yourself using a few of them. Your workplace may even have some specific jargon only used in your organization, Rock Chalk!

Colloquialisms

Colloquialisms are the use of informal words in communication.25 Colloquialisms vary from region to region. Examples might be “wanna” instead of “want to” or “gonna” instead of “going to.” It shows us how a society uses language in their everyday lives. Here’s a short list of some common colloquialisms you may have used yourself:

- Bamboozle – to deceive

- Be blue – to be sad

- Beat around the bush – to avoid a specific topic

- Gonna – going to

- Hit a writer’s block – unable to write

- Hit the hay – to go to sleep

- Threw me for a loop – to be surprised

- Throw someone under the bus – to throw the blame on another person

- Wanna – want to

- Y’all – you all

- Yinz – you all

Slang

Slang refers to words that are employed by certain groups, such as young adults and teens, or even older generations.26 Slang is more common when speaking to others rather than written. Slang is often used with people who are similar and have experience with each other. Here is a list of some common slang associated with the millennial generation:

- Dude

- My bad

- For real

- Sick, wicked

- Chill

- Not gonna lie

- Adulting

- Basic

How many of these slang words do you use? What other slang words do you find yourself using? When it comes to slang, it’s important to understand that this list is constantly evolving. What is common slang today could be completely passé tomorrow. What’s common slang in the United States is not universal in English speaking countries.

Idioms

Idioms are expressions or figures of speech whose meaning cannot be understood by looking at the individual words and interpreting them literally.27 Idioms can help amplify messages or be used to provide artistic expression. For instance, “knowledge is power!”

Idioms can be hard to grasp for non-native speakers. As such, many instructors in the English as a Second Language world spend a good deal of time trying to explain idioms to non-native speakers. There are many extensive lists of idioms available online. Table 4.2 presents just a few different idiom examples.

| Reused here from Kifissia under a Creative Commons Attribution License. https://tinyurl.com/rtxklo5 | |

| IDIOM | MEANING/SENTENCE |

|---|---|

| a breath of fresh air | Refreshing/fun. She’s a breath of fresh air. |

| a change of heart | Change my mind. I’ve had a change of heart. |

| a blessing in disguise | Something bad that turns out good. Losing his job turned out to be a blessing in disguise. |

| pull someone’s leg | Kid someone. Stop pulling my leg. I know you are kidding! |

| red tape | Bureaucracy. It’s almost impossible to set up a business in Greece because there is so much red tape. |

| you can say that again | You agree emphatically. Kanye West is a great singer. You can say that again! |

| you name it | Everything you can think of. This camp has every activity you can think it–like swimming, canoeing, basketball and you name it. |

| wouldn’t be caught dead | Not even dead would I do something. I wouldn’t be caught dead wearing that dress to the ball. |

| get off my back | Leave me alone. Bug off! Get off my back! |

| drive me up a wall | Drive me crazy. Rude people drive me up a wall. |

| spill the beans | Tell a secret. Hey, don’t spill the beans. It’s a secret. |

| like beating a dead horse | A waste of time. Trying to get my father to ever change his mind is like beating a dead horse. |

| out of this world | Fantastic! My vacation to Hawaii was out of this world! |

| break the ice | Start a conversation. Talking about the weather is a good way to break the ice when you meet someone new. |

| give me a break | Leave me alone! Come on! Give me a break! I’ve been working all day long- and I just want to play a little bit of Angry Birds…. |

Table 2 Common Idioms

Clichés

Cliché is an idea or expression that has been so overused that it has lost its original meaning.28 Clichés are common and can often be heard. For instance, “light as a feather” or “happily ever after” are common clichés. They are important because they express ideas and thoughts that are popular in everyday use. They are prevalent in advertisements, television, and literature.

Biased Language

Biased language is language that shows preference in favor of or against a certain point-of-view, shows prejudice, or is demeaning to others.30 Bias in language is uneven or unbalanced. Examples of this may include “mankind” as opposed to “humanity.”

| Avoid | Consider Using |

|---|---|

| Businessman | Businessperson, Business Owner, Executive, Leader, Manager, etc. |

| Chairman | Chair or Chairperson |

| Cleaning Lady / Maid | Cleaner, Cleaning Person, Housecleaner, Housekeeper, Maintenance Worker, Office Cleaner, etc. |

| Male Nurse | Nurse |

| Male Flight Attendant or Stewardess | Flight Attendant |

| Female Doctor | Physician or Doctor |

| Manpower | Personnel or Staff |

| Congressman | Legislator, Member of Congress, or Member of the House of Representatives |

| Postman | Postal Employee or Letter carrier |

| Disabled | People with Disabilities |

| Schizophrenic | Person Diagnosed with Schizophrenia |

| Homosexual | Lesbians, Gay Men, Bisexual Men or Women |

Table 3 Biased Language

Sexism, Hetero-/Cis-Normativity, and Racism

Before discussing the concepts of sexism and racism, we must understand the term “bias.” Bias is an attitude that is not objective or balanced, prejudiced, or the use of words that intentionally or unintentionally offend people or express an unfair attitude concerning a person’s race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, disability, or illness. Sexism or bias against others based on their sex can come across in language. Sexist language can be defined as “words, phrases, and expressions that unnecessarily differentiate between females and males or exclude, trivialize, or diminish either sex.”18 Language can impact how we feel about ourselves and others. For instance, there is a magazine called Working Mother, but there is not one called “Working Father.” Even though the reality is that many men who work also have families and are fathers, there are no words that tend to distinguish them from other working men. Whereas, women are distinguished when they both work and are mothers compared to other women who solely work and also compared to women who are solely mothers and/or wives.

Think about how language has changed over the years. We used to have occupations that were highly male-dominated in the workplace and had words to describe them. For instance, policemen, firemen, and chairmen are now police officers, firefighters, and chairpersons. The same can also be said for some female-dominated occupations. For instance, stewardess, secretary, and waitress have been changed to include males and are often called flight attendants, office assistants, and servers. Thus, to eliminate sexism, we need to be cautious of the word choices we use when talking with others. Sexist language will impact perceptions, and people might be swayed about a person’s capability based on the word choices.

Hereonormativity, a bias whereby people assume that others are heterosexual, is also pervasive in social interactions. For example, a young female might be asked “Do you have a boyfriend?” Heteronormativity manifests in language, and can make others feel ostracized or excluded because it involves language that articulates underlying biases. But here too language is changing, it is increasingly common for people to use the term “partner” to refer to a romantic companion. Cisnormativity , a bias involving presumptions about gender assignment, such as the presumption of a gender binary, or expectations of conformity to gender roles even when transgender identities are otherwise acknowledged, also creates challenges for individuals who do not ascribe to binary gender (e.g., agender, gender fluid, trans individuals, etc.). Trans and non-binary people who were able to freely express their gender identity were on average 20% more satisfied with their life and their job in a recent study.12

Biases about race also manifest in language, racism is the bias people have towards others of a different race. Racist language conveys that a racial group is superior or better than another race. Some words in English have racial connotations. Smith-McLallen and colleagues explain:

In the United States and many other cultures, the color white often carries more positive connotations than the color black… Terms such as “Black Monday,” “Black Plague”, “black cats” and the “black market” all have negative connotations, and literature, television, and movies have traditionally portrayed heroes in white and villains in black. The empirical work of John E. Williams and others throughout the 1960s demonstrated that these positive and negative associations with the colors black and white, independent of any explicit connection to race, were evident among Black and White children as young as 3 years old … as well as adults.19

Former President Trump’s use of the phrase “Chinese Virus” when referring to the coronavirus was racially insensitive. The former President is specifically using the term as an “other” technique to allow his followers to place blame on Chinese people for the coronavirus. Unsurprisingly, as a result of the use of the phase “Chinese Virus,” there have been numerous violent attacks against individuals of Asian descent within the United States. Notice that we don’t say people of Chinese descent here. The people that are generally inflamed by this rhetoric don’t take the time to distinguish among people they label as “other.”

It is important to note that many words do not imply any type of sexual or racial connotations. However, some people might use it to make judgments or expectations of others. For example, when describing a bad learning experience, the student might say “Black professor” or “female student” as opposed to just saying the student and professor argued. These descriptors can be problematic and sometimes not even necessary in the conversation. When using those types of words, it can create slight factors of sexism/racism.

Ambiguous Language

Ambiguous language is language that can have various meanings. Google Jay Leno’s headlines videos. Sometimes he uses advertisements that are very abstract. For instance, there is a restaurant ad that says, “People are our best ingredient!” What comes to mind when you hear that? Are they actually using people in their food? Or do they mean their customer service is what makes their restaurant notable? When we are trying to communicate with others, it is important that we are clear in our language. We need others to know exactly what we mean and not imply meaning. That is why you need to make sure that you don’t use ambiguous language.

Euphemisms

Euphemisms also make language unclear. People use euphemisms as a means of saying something more politely or less bluntly. For instance, instead of telling your parents/guardians that you failed a test, you might say that you did sub-optimal. People use euphemisms because it sounds better, and it seems like a better way to express how they feel. People use euphemisms all the time. For instance, instead of saying this person died, they might say the person passed away. Instead of saying that someone farted, you might say someone passed gas.

Relative Language

Relative language depends on the person communicating. People’s backgrounds vary. Hence, their perspectives will vary. I know a college professor that complains about her salary. However, other college professors would love to have a salary like hers. In other words, our language is based on our perception of our experiences. For instance, if someone asked you what would be your ideal salary, would it be based on your previous salary? Your parents? Your friends? Language is relative because of that reason. If I said, “Let’s go eat at an expensive restaurant,” what would be expensive for you? For some person, it would be $50, for another, $20, for someone else it might be $10, and yet there might be someone who would say $5 is expensive!

Key Takeaways

- Communication is symbolic, and words are a common and important symbol.

- Words and meanings are socially and culturally connected.

- The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis proposes a range between linguistic relativism and linguistic determinism.

- Language has many functions and forms that are both formal and informal in nature.

- Language creates reality, and biases can be encoded in language.

Key Terms

abstract

Refers to words that relate to ideas or concepts that exist only in your mind and do not represent a tangible object.

abstraction ladder

A diagram that explains the process of abstraction.

affiliation

A connection or association with others.

ambiguous language

Language that has multiple meanings.

bias

An attitude that is not objective or balanced, prejudiced, or the use of words that intentionally or unintentionally offend people or express an unfair attitude concerning a person’s race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, disability, or illness.

biased language

Language that shows preference in favor of or against a certain point-of-view, shows prejudice, or is demeaning to others.

buzz word

Informal word or jargon used among a particular group of people.

cliché

Expression that has been so overused that it has lost its original meaning.

colloquialism

Informal expression used in casual conversation that is often specific to certain dialects or geographic regions of a country.

connotation

What a word suggests or implies; connotations give words their emotional impact.

converge

Adapting your communication style to the speaker to be similar.

denotation

The dictionary definition or descriptive meaning of a word.

discourse

Spoken or written discussion of a subject.

diverge

Adapting your communication style to the speaker to be drastically different.

euphemism

Replacing blunt words with more polite words.

formal language

Official or academic language.

heuristic function

The use of language to explore and investigate the world, solve problems, and learn from your discoveries and experiences.

idiom

Expression or figure of speech whose meaning cannot be understood by looking at the individual words and interpreting them literally.

imaginative function

The use of language to play with ideas that do not exist in the real-world.

informal language

Common, everyday language people use during most interpersonal interactions.

instrumental function

The use of language as a means for meeting your needs, manipulating and controlling your environment, and expressing your feelings.

interactional function

The use of language to help you form and maintain relationships.

jargon

The specialized or technical language of a specific group or profession that may not be understood by outsiders.

language

A system of human communication using a particular form of spoken or written words or other symbols.

language adaptation

The ability to alter one’s linguistic choices in a communicatively competent manner

language awareness

a person’s ability to be mindful and sensitive to all functions and forms of language.

linguistic determinism

The perspective that language influences thoughts.

linguistic relativity

The argument that the structure of a language influences its speakers’ worldview or cognition, and thus individuals’ languages determine or influence their perceptions of the world.

metamessage

The meaning beyond the words themselves.

personal function

The use of language to help you form your identity or sense of self.

racism

bias against others on the basis of their race or ethnicity.

racist language

Language that demeans or insults people based on their race or ethnicity.

regulatory function

The use of language to control behavior.

relative language

Language that gains understanding by comparison.

representational function

The use of language to represent objects and ideas and to express your thoughts.

Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

A theory that suggests that language impacts perceptions. Language is ascertained by the perceived reality of a culture.

sexism

Bias of others based on their biological sex.

sexist language

Language that excludes individuals on the basis of gender or shows a bias toward or against people due to their gender.

slang

The nonstandard language of a particular culture or subculture.

spin

The manipulation of language to achieve the most positive interpretation of words, to gain political advantage, or to deceive others.

static evaluation

Language shows that people and things change.

vocabulary

All the words understood by a person or group of people.

Notes

A system of human communication using a particular form of spoken or written words or other symbols.

A mark, object, or sign that represents something else by association, resemblance, or convention

Definitions for words commonly found in dictionaries.

The emotions or associations a person makes when exposed to a symbol.

the dictionary definition of the word

Refers to words that relate to ideas or concepts that exist only in your mind and do not represent a tangible object.

A diagram that explains the process of abstraction.

communication about communication

The meaning beyond the words themselves.

something that represents or signifies something else (e.g., the word 'dog')

The use of language as a means for meeting your needs, manipulating and controlling your environment, and expressing your feelings.

The use of language to control behavior.

The use of language to help you form and maintain relationships.

language which helps to create imaginary constructs and tell stories

The use of language to help you form your identity or sense of self.

The use of language to explore and investigate the world, solve problems, and learn from your discoveries and experiences.

The use of language to represent objects and ideas and to express your thoughts.

A theory that suggests that language impacts perceptions. Language is ascertained by the perceived reality of a culture.

The perspective that language influences thoughts.

The argument that the structure of a language influences its speakers' worldview or cognition, and thus individuals' languages determine or influence their perceptions of the world.

A connection or association with others.

Adapting your communication style to the speaker to be similar.

Adapting your communication style to the speaker to be drastically different.

Differences in language use based on the environment, who you are talking to, and the reason for communicating.

Specific writing and spoken style that adheres to strict conventions of grammar that uses complex sentences, full words, and third-person pronouns.

Specific writing and spoken style that is more colloquial or common in tone; contains simple, direct sentences; uses contractions and abbreviations; and allows for a more personal approach that includes emotional displays.

The specialized or technical language particular to a specific profession, occupation, or group that is either meaningless or difficult for outsiders to understand.

Informal expression used in casual conversation that is often specific to certain dialects or geographic regions of a country.

The nonstandard language of a particular culture or subculture.

Expression or figure of speech whose meaning cannot be understood by looking at the individual words and interpreting them literally.

Idea or expression that has been so overused that it has lost its original meaning.

Language that shows preference in favor of or against a certain point-of-view, shows prejudice, or is demeaning to others.

An attitude that is not objective or balanced, prejudiced, or the use of words that intentionally or unintentionally offend people or express an unfair attitude concerning a person’s race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, disability, or illness.

Bias of others based on their biological sex.

Language that excludes individuals on the basis of gender or shows a bias toward or against people due to their gender.

a bias whereby people assume that others are heterosexual

A bias involving presumptions about gender assignment, such as the presumption of a gender binary, or expectations of conformity to gender roles even when transgender identities are otherwise acknowledged.

Bias against others on the basis of their race or ethnicity.

Language that demeans or insults people based on their race or ethnicity.

Language that has multiple meanings.

Replacing blunt words with more polite words.

Language that gains understanding by comparison.