Finding Credible Sources and Creating Citations

Learning Objectives

- Explain different information types.

- Describe types of plagiarism.

- Learn how to properly cite sources in APA format.

Research

What does the word “research” conjure up for you? Do you think about sitting in a library and sorting through books or searching online? Do you picture a particular type of person?

While these images aren’t incorrect (of course libraries are connected with research), “research” can feel like an intimidating process. When does it begin? Where does it happen? When does it stop?

It’s helpful to understand what research is – the process of discovering new knowledge and investigating a topic from different points of view. Research is a process; it’s an ongoing dialogue with information. But, as you know, not all information is neutral, and not all information is ethical. Part of the research process, then, is evaluating information to determine what knowledge is ethical and best suited for your argument.

This chapter will focus on the research process and the development of critical thinking skills—or decision-making based on evaluating and critiquing information— to identify, sort, and evaluate (mostly) scholarly information. To begin, we outline why research matters, followed by insights about locating information, evaluating information, and avoiding plagiarism.

Why Research?

Research gets a bad rap. It can feel like a boring, tedious, and overwhelming process. In our current information age, we are guilty of conducting a quick search, finding what we want to read, and moving on. Many of us rarely sit down, allocate time, and commit to digging deep and researching different perspectives about an idea or argument.

But we should.

When conducting research, you get to ask questions and actually find answers. If you have ever wondered what the best strategies are when being interviewed for a job, research will tell you. If you’ve ever wondered what it takes to be a NASCAR driver, an astronaut, a marine biologist, or a university professor, once again, research is one of the easiest ways to find answers to questions you’re interested in knowing.

Research can also open a world you never knew existed. We often find ideas we had never considered and learn facts we never knew when we go through the research process. Maybe you want to learn how to compose music, draw, learn a foreign language, or write a screenplay; research is always the best step toward learning anything.

As public speakers, research will increase your confidence and competence. The more you know, the more you know. The more you research, the more precise your argument, and the clearer the depth of the information becomes.

Where to Start

With that basic information in mind, ask: “what question am I answering? What should I be looking for? What do I need?” Your specific purpose statement or a working thesis are good places to start.

When we begin researching, we have three initial questions that arise from our specific purpose: has the cost of college textbooks increased over time? What are the causes? And what are the opportunities to address rising textbook costs in a way that can improve access relatively quickly at your institution?

These are just our starting questions. It’s likely that we’ll revise and research for information as we learn more. As Howard and Taggart point out in their book Research Matters, research is not just a one-and-done task (2010). As you develop your speech, you may realize that you want to address a question or issue that didn’t occur to you during your first round of research, or that you’re missing a key piece of information to support one of your points.

Use these questions, prior experience, and insight from exploratory brainstorming to determine what to search and where to start. If you still feel overwhelmed, that’s OK. Start somewhere (or ask a librarian for help), and use the insights below about information types as a guide.

Locating Effective Research

Once you have a general idea about the basic needs you have for your research, it’s time to start tracking information down. Thankfully, we live in a world that is swimming with information.

As you search, you will naturally be drawn to tools and information types that are already familiar to you. Like most people, you will likely use Google as your first search strategy. As you know, Google isn’t a source, per se: it’s a search engine. It’s the vehicle that, through search terms and savvy wording, will direct you to sources related to those terms.

What information types would you expect to see in your Google search results? We are guessing your list would include: news, blogs, Wikipedia, dictionaries, and social media.

While Google is a great tool, all informational roads don’t lead to Google. Learning about different information types and different ways to access information can expand your search portfolio.

Information Types

As you begin looking for research, an array of information types will be at your disposal.

When you access a piece of information, you should determine what you are looking at. Is it a blog? an online academic journal? an online newspaper? a website for an organization? Will these information types be useful in answering the questions that you’ve identified?

Common helpful information types include websites, scholarly articles, books, and government reports, to name a few. To determine the usefulness of an information type, you should familiarize yourself with what those sources are and their goals.

Information types are often categorized as either academic or nonacademic.

Nonacademic information sources are sometimes also called popular press information sources; their primary purpose is to be read by the general public. Most nonacademic information sources are written at a sixth to eighth-grade reading level, so they are very accessible. Although the information often contained in these sources can be limited, the advantage of using nonacademic sources is that they appeal to a broad, general audience.

Alternatively, academic sources are often (not always) peer-reviewed by like-minded scholars in the field. Academic publications can take longer to publish because academics have established a series of checklists that are required to determine the credibility of the information. Because of this process, it takes a while! That delay can result in nonacademic sources providing information before scholarly academics have tested or studied the phenomena.

In addition, be cognizant of who produces information and who that information is produced for. Table 16.1 simplistically illustrates the producer and audience of our short list of information types.

|

Information Type |

What does it do? |

Who is it produced by? |

Who is it produced for? |

|

News Report |

Inform readers about what’s happening in the world. |

General Public / Journalist |

General Public |

|

Social Media |

Connects individuals, groups, and consumers |

General Public |

General Public |

|

Peer Reviewed Scholarly Journal Article |

Provides insight into an academic discipline |

Academic Researchers/Scholars |

Academic Researchers/Scholar/ Students |

|

Academic Books |

Provides insight into an academic discipline |

Academic researchers/Scholars |

Academic Researchers/Scholars /Students |

|

Government reports |

Shares information on behalf of a government agency |

Government Agencies |

Policy/Decision Makers |

|

Data and Statistics |

Reports statistical findings |

Government Agencies |

Policy/Decision Makers Academic Researcher |

|

E-books |

Inform, persuade, or entertain readers about a topic through a digital medium |

Can be Self-Published or Published through a Scholar / Agency |

General Public |

| Table 1 |

This is not an exhaustive list of information types. Others include: encyclopedias, periodicals or blogs. For more insight on information types, check here.

With any information type, the dichotomy of producer/audience helps us with evaluating the information. As you’ve learned from our discussion of public speaking, the audience informs the message. If you have a clearer idea of who the content is written for, you can determine if that source is best for your research needs.

Having a better understanding of information types is important, but open and closed information systems dictate which source material we have access to.

Open/Closed Information Systems

An open system describes information that is publicly available and accessible. A closed system means information is behind a paywall or requires a subscription.

Let’s consider databases as an example. It’s likely that you’ve searched your library’s database. Databases provide full text periodicals and works that are regularly published. This is a great tool because it can provide you links to scholarly articles, news reports, e-books, and more.

“Does that make databases an open system?” you may be asking. Access to databases is purchased by libraries. The articles and books contained in databases are licensed by publishers to companies, who sell access to this content, which is not freely available elsewhere. So, databases are part of a closed system. The university provides you access, but non-university folks would reach a paywall.

Table 2 illustrates whether different information types are like to be openly available or behind a paywall in a closed system. Knowing if an information is type is open or closed might influence your tools and search strategies used to discover and access the information.

|

Information Type |

Open Access |

Closed Access |

|

News Report |

Some content exposed to internet search engines and open |

Licensed content available with subscription or single access payment

|

|

Social Media |

General public and open |

Privacy settings may limit some access |

|

Peer Reviewed Scholarly Journal Article |

Scholarship labeled as “Open access” are free of charge |

Licensed content available with subscription or single access payment

|

|

Academic Books |

“Open access” books are free of charge |

Many books require payment and purchase |

|

Government Reports |

Government information in the public domain is open |

Classified government information – restricted access

|

|

Government Data/Statistics |

Open government data |

Classified government information – restricted access |

| Table 2 |

Information isn’t always free. If you are confronted with a closed system, you will have to determine if that information is crucial or if you can access similar information through an openly accessible system.

Having a better understanding of information types and access will assist you in locating research for your argument. We continue our discussion below by diving into best practices for locating and evaluating research.

Evaluating Research

Going Deeper through Lateral Reading

Imagine that you’re online shopping. You have a pretty clear idea of what you need to buy, and you’ve located the product on a common site. In a perfect world, you could trust the product producer, the site, and the product itself and, without any research, simply click and buy. If you’re like us, however, being a knowledgeable consumer means checking product reviews, looking for similar products, and reading comments about the company. Once we have a deeper understanding of the product and process, then we buy!

Argument research is similar. Feeling literate about the information types described above is key, but inaccurate or untrustworthy content still emerges.

In response, we recommend lateral reading – fact-checking source claims by reading other sites and resources.

Lateral reading emerged after a group of Stanford researchers pitted undergraduates, professors with their Ph.D.s in history, and journalists against each other in a contest to see who could tell if information was fake or real (Wineburg, McGrew, 2017). The results? Journalists identified fake information every time, but the Ph.D.s and undergraduates struggled to sniff out the truth.

Why is this?

Well, journalists rarely read much of the article or website they were evaluating before they dove into researching it. They would read the title and open a new tab to check out if anyone else had published something on the same topic. Reading what other people had written gave the journalists some context or background knowledge on the topic, better positioning them to judge the argument and evidence made. They would circle back to the original article, identify the author, and open more tabs to verify the identity of the author and their credentials to write the piece. Once the journalists were satisfied with this, they had enough background information to start judging the argument of the original piece. Essentially, journalists would read the introduction and pick out big ideas or the argument, people, specific facts, and the evidence referenced in the first paragraph.

Mike Caulfield (2017), a professor who specializes in media literacy, read the Stanford study and identified steps to evaluate sources. One of those steps is to read laterally, and three additional steps include:

- Check for previous work: Look around to see if someone else has already fact-checked the claim or provided a synthesis of research.

- Go upstream to the source: Go “upstream” to the source of the claim. Most web content is not original. Get to the original source to understand the trustworthiness of the information.

- Circle back: If you get lost, hit dead ends, or find yourself going down an increasingly confusing rabbit hole, back up and start over, knowing what you know now. You’re likely to take a more informed path with different search terms and better decisions.

Lateral reading is a great tool to verify information and learn more without getting too bogged down. However, your research doesn’t stop there. As you begin compiling information source types around your argument, verify the credibility and make sure you’re taking notes.

Questioning Selected Source Information

Practicing lateral reading will provide you better insight on what diverse sources say about your argument. Through that process, you’ll likely find multiple relevant sources, but is that source best for your argument? Perhaps, but ask yourself the following questions before integrating others’ ideas or research into your argument:

- What’s the date? Remember that timeliness plays a key role in establishing the relevance of your argument to your audience. Although a less timely source may be beneficial, more recent sources are often viewed more credibly and may provide updated information.

- Who is the author / who are the authors? Identify the author(s) and determine their credentials. We also recommend “Googling” an author and checking if there are any red flags that may hint at their bias or lack of credibility.

- Who is the publisher? Find out about the publisher. There are great, credible publishers (like the Cato Institute), but fringe or for-profit publishers may be providing information that overtly supports a political cause.

- Do they cite others’ work? Check out the end of the document for a reference page. If you’re using a source with no references, it’s not automatically “bad,” but a reputable reference page means that the author has evidence to support their insights. It helps establish if that author has done their research, too.

- Do others cite the work? Use the lateral reading technique from above to see if other people have cited this work, too. Alternatively, if, as you research, you see the same piece of work over and over, it’s likely seen as a reputable source within that field. So check it out!

It can feel great to find a key piece of information that supports your argument. But a good idea is more than well-written content. To determine if that source is credible, use the questions above to guarantee that you’re selecting the best research for your idea.

Take Notes

Remember: this is a lot of stuff to keep track off. We suggest jotting down notes as you go to keep everything straight. Your notes could be a pad of paper next to your laptop or a digital notepad – whatever works best for you.

This may seem obvious, but it is often overlooked. Poor note taking or inaccurate notes can be devastating in the long-term. If you forget to write down all the source information, backtracking and trying to re-search to locate citation information is tedious, time-consuming, and inefficient. Without proper citations, your credibility will diminish. Keeping information without correct citations can have disastrous consequences – as discussed below.

Plagiarism

While issues of plagiarism are mostly present in written communication, the practice can also occur in oral communication and in communication studies courses. It can occur when speakers misattribute or fail to cite a source during a speech, or when they are preparing outlines or notecards to deliver their speeches and fail to cite sources.

According to the National Communication Association (NCA), “ethical communication enhances human worth and dignity by fostering truthfulness, fairness, responsibility, personal integrity, and respect for self and others” and truthfulness, accuracy, honesty, and reason as essential to the integrity of communication (“Credo for Ethical Communication,” 2017). This would imply that through oral communication, there is an expectation that you will credit others with their original thoughts and ideas through citation. One important way that we speak ethically is to use material from others correctly. Occasionally we hear in the news media about a politician or leader who uses the words of other speakers without attribution or of scholars who use pages out of another scholar’s work without consent or citation.

But, why does it matter if a speaker or writer commits plagiarism? Why and how do we judge a speaker as ethical? Why, for example, do we value originality and correct citation of sources in public life as well as the academic world, especially in the United States? These are not new questions, and some of the answers lie in age-old philosophies of communication.

Although there are many ways that you could undermine your ethical stance before an audience, the one that stands out and is committed most commonly in academic contexts is plagiarism. A dictionary definition of plagiarism would be “the act of using another person’s words or ideas without giving credit to that person” (Merriam-Webster, 2015). Plagiarism is often thought of as “copying another’s work or borrowing someone else’s original ideas” (“What is Plagiarism?”, 2014). Plagiarism also includes:

- Turning in someone else’s work as your own;

- Copying words or ideas from someone else without giving credit;

- Failing to put quotation marks around an exact quotation correctly;

- Giving incorrect information about the source of a quotation;

- Changing words but copying the sentence structure of a source without giving credit;

- Copying so many words or ideas from a source that it makes up the majority of your work, whether you give credit or not.

Plagiarism exists outside of the classroom and is a temptation in business, creative endeavors, and politics. However, in the classroom, your instructor will probably take the most immediate action if he or she discovers your plagiarism either from personal experience or through using plagiarism detection (or what is also called “originality checking”) software.

In the business or professional world, plagiarism is never tolerated because using original work without permission (which usually includes paying fees to the author or artist) can end in serious legal action. So, you should always work to correctly provide credit for source information that you’re using.

Types of Plagiarism

There are many instances of speakers or authors presenting work they claim to be original and their own when it is not. Plagiarism is often done accidentally due to inexperience. To avoid this mistake, let’s work through two types of plagiarism: stealing and sneaking. Sometimes these types of plagiarism are intentional, and sometimes they occur unintentionally (you may not know you are plagiarizing). However, as everyone knows, “Ignorance of the law is not an excuse for breaking it.”

Stealing

No one wants to be the victim of theft; if it has ever happened to you, you know how awful it feels. When someone takes an essay, research paper, speech, or outline completely from another source, whether it is a classmate who submitted it for another instructor, from some sort of online essay writing service, or from elsewhere, this is an act of theft. The wrongness of the act is compounded when someone submits that work in its entirely and labels it as their own.

Most colleges and universities have a policy that penalizes or forbids “self-plagiarism.” This means that you can’t use a paper or outline that you presented in another class a second time. You may think, “How can this be plagiarism if the source is in my works cited page?” The main reason is that by submitting it to your instructor, you are still claiming it is original, first-time work for the assignment in that particular class. Your instructor may not mind if you use some of the same sources from the first time it was submitted, but he or she expects you to follow the instructions for the assignment and prepare an original assignment. In a sense, this situation is also a case of unfairness, since the other students do not have the advantage of having written the paper or outline already.

Sneaking

Instead of taking work as a whole from another source, an individual might copy two out of every three sentences and mix them up so they don’t appear in the same order as in the original work. Perhaps the individual will add a fresh introduction, a personal example or two, and an original conclusion. This kind of plagiarism is easy today due to the Internet and the word processing functions of cutting and pasting. It also most often occurs when someone has waited too long to start a project and it seems easier to cut and paste portions of text than it is to read, understand, and synthesize information into their own words.

You might not view this as stealing, thinking, “I did some research. I looked some stuff up and added some of my own work.” Unfortunately, this is still plagiarism because no source was credited, and the individual “misappropriated” the expression of the ideas as well as the ideas themselves.

Avoiding Plagiarism

To avoid plagiarism, you must give credit to the words, research, or insights of others. When you’re integrating supporting research or using a key idea or theory, let the audience know! As you add research into your outline, you can either:

- Use direct quotes: this means that you’re including information from a source verbatim.

- Paraphrase: express the source’s idea but not verbatim.

- Summarize: explain the main ideas or arguments from the source’s findings.

Citing others will bolster your credibility because it demonstrates that you have in-depth knowledge about the topic.

In English classes, you’ve likely used style guides (like MLA or APA) to ethically cite research in an essay. Continue this practice. Regardless of how you’re integrating that research – verbatim or paraphrasing—the source reference should appear both in the writing and through an oral citation.

Key Takeaway

- Using Oral Citations: research must be orally cited in a speech to note where you’re using ideas, concepts, or findings from someone else’s work. Rehearse your oral citations and be clear about why that source is credible for your topic.

Citing Your Sources

Now that you’ve learned effective strategies for searching for, accessing, and evaluating sources, let’s review the final stage of the research process: using those sources in your project. In this section you will learn the basics about citations and using sources ethically.

Why cite sources?

As a writer, there are also reasons to cite your sources:

- to meet the requirements for your assignment,

- to give the original creators credit for their ideas,

- to help your readers find and learn from the sources you used, and

- to lend credibility to your argument.

You are likely familiar with the first three reasons already, so let’s examine the last one in more detail. How does citing sources lend credibility to your argument? Research projects involve reading, analyzing, and synthesizing information from multiple sources and using their ideas to inform your work. There is a common misconception that academic research consists of one person making amazing breakthroughs all alone in their lab or office, but that’s not what actually happens in most cases. Instead, research is a process where scholars build on older work while sharing their new ideas. When you cite others’ research, you’re doing the same thing. By citing a scholar that has done research on your topic area, you are using their authority and experience to support your claims, and adding your own insights.

When to cite

Whenever you use someone else’s ideas, you need to cite them. This is true for any source where there is interpretation involved (opinions, research findings, recent discoveries, statistics, etc). In the examples below, we’ve bolded words that indicate you probably need to cite a source:

- Some biographers of Abraham Lincoln say he suffered from clinical depression. (Which biographers?)

- The quart measurement might have originated in medieval England as a measurement for beer. (Says who?)

- 60% of art majors believe that Pablo Picasso’s paintings are more interesting than his sculptures. (Where did this percentage come from?)

- In recent studies of Y-chromosomes, geneticists have found that Genghis Khan has approximately 16 million descendants living today. (Where did they get that number?)

No matter where ideas come from you still need to cite them, whether they’re from images, tables, charts, statistics, websites, podcasts, interviews, emails, speeches, songs, movies, or any other source.

How to Cite

Once you have done your research and found sources, the next step is writing your paper. As you write, you’ll need to communicate your ideas to your audience. You’ll also need to demonstrate that you know how to integrate others’ ideas in your writing in an ethical, clear, and consistent way. This means incorporating citations when paraphrasing or using direct quotes.

Cite purposefully

Citations aren’t just there to fill up space. Each citation you include in your paper should be relevant and serve a purpose. Maybe you agree with the author and wish to further explore their main points. Or perhaps you disagree with their conclusions and wish to explain your own perspectives. In either case, the ideas you are citing must somehow add to your argument. Keep in mind that no single article or book will be exactly what you need. To strengthen your argument, you need to examine the work of multiple authors.

When to use direct quotes

Sometimes an author presents an idea in a way that you cannot rephrase without losing something important from the original quote. In these cases, you can use a direct quote by copying the text and putting it into your paper with quotation marks around the phrase –and citing, of course!

When you do this, keep the quote as short as you can and still make your point. Be careful not to rely too heavily on quoted material. Remember, the purpose of research is to make an original argument, and not to just pull together big blocks of quotes.

You may have been told at some point that you don’t need to use quotation marks unless you copy some specific number of words in a row from an author’s work. There’s more to it than that. If the author has used words or phrases in a distinctive way, make sure that you use quotation marks if you use the same words in your paper. For example, a source might define a new process or system that must be cited, such as “action painting,” a term which combines common words in a new way, and was coined by a specific art critic.

Common knowledge

Common knowledge is factual information that can easily be verified in multiple authoritative sources (e.g., encyclopedias, dictionaries, reputable websites, and books). You always need to cite things like opinions, ideas, or new research findings, but well-established facts don’t need citations. Even if it’s something new to you, if it’s a long-held fact, it is considered common knowledge and doesn’t need to be cited.

Here are some types of common knowledge, with examples of each:

- Widely-known facts: that water boils at 100° Celsius.

- Uncontested historical dates: 1776 was the year the Declaration of Independence was signed in the United States of America.

- Well-known cultural references, such as important facts, people, or historical events within that culture: Suleiman the Magnificent was the longest ruling sultan of the Ottoman Empire.

These examples were adapted from MIT’s Academic Integrity Handbook for Students.1

Be aware that some common knowledge may also be contextual. For example, what is common knowledge among microbiologists may not be common knowledge among lawyers, and vice versa. But if you have any doubt whether something is or isn’t common knowledge, the best practice is to cite.

Citations

A citation contains elements (e.g. author, date, title) that uniquely identify a resource. You will primarily find citations in the works cited or reference section of a paper or book. They may also appear on websites, your course syllabus, or other materials provided by your instructor. Your instructors expect you to include citations in your papers to tell them where your ideas came from. Scholars out in the wider world include citations in their work for the same purpose. You can use their citations to trace back where their ideas originated, the same way your instructors check your work.

You may be familiar with different citation styles. Some fields have only one citation style, while others have multiple. Note that different citation styles (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc.) will have different rules or ways of representing common elements of citations, such as author name, title of article or book, and so on. Often times, particular journals have specific guidelines for the exact citation style they prefer. In this course, we will use APA.

APA Citation Examples

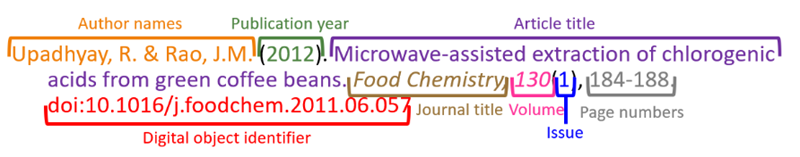

Example Journal citation in APA style:

Upadhyay, R. & Rao, J.M. (2012). Microwave-assisted extraction of chlorogenic acids from green coffee beans. Food Chemistry, 130(1), 184-188. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.06.057

Typical article citation elements include author and title of the article, journal name, journal volume and issue numbers. There are several ways to find a journal article from a citation. You can search for the article by its title or by the journal it’s found within.

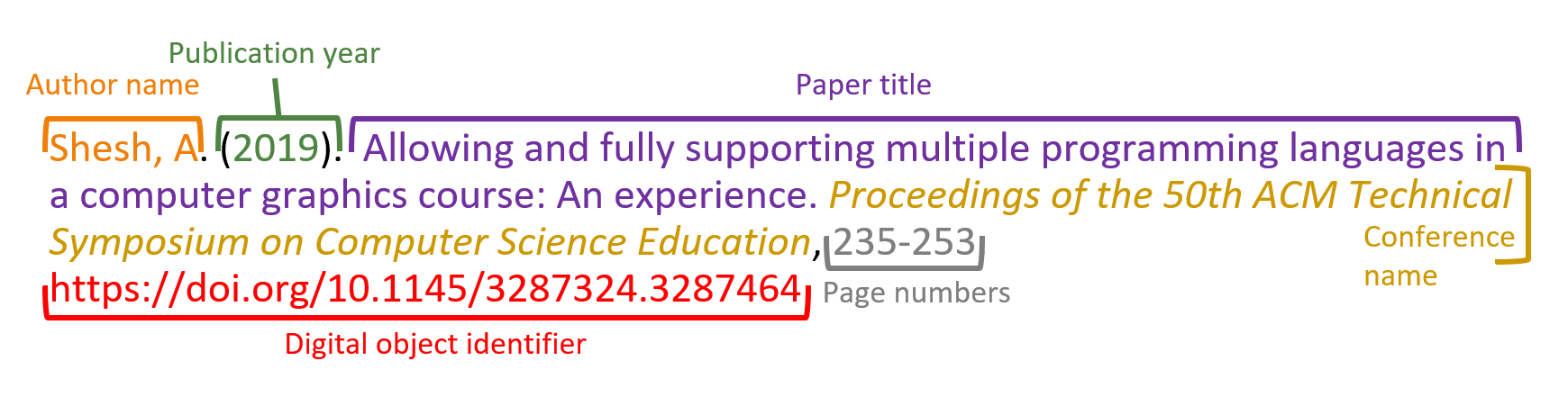

Example Conference Presentation citation (APA):

Shesh, A. (2019). Allowing and fully supporting multiple programming languages in a computer graphics course: An experience. Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, 235-253. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287324.3287464

Example Newspaper Article Citation (APA):

Reynolds, G. (2019, May 1). How exercise affects our memory. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/01/well/move/how-exercise-affects-our-memory.html

It is imperative that you learn how to properly cite your sources. For more information on APA citations, please reference APA Citation Style Guidelines (APA Style). Additional resources may be found at Owl Purdue APA (APA Formatting and Style Guide (7th Edition) – Purdue OWL® – Purdue University).

Key Takeaways

- Finding credible research is imperative. There are many ways to evaluate and determine if information is trustworthy.

- Plagiarism is a serious issue that can be remedied by giving credit to original work.

Conclusion

Having a strong research foundation will give your speech interest and credibility. This chapter has shown you how to access information but also how to find reliable information and evaluate it.

This process may seem exhausting at first, but you likely already are doing this in your everyday life. We simply are asking you to be a bit more aware of and practice lateral reading. Doing so will help you better understand the context and judge the veracity of an author’s argument and their evidence. It will also likely give you plenty of new evidence to inform your own argument.

Learning how to cite sources properly is a beneficial skill that increases your credibility. Giving proper credit is ethical.

Glossary

Academic sources

Often (not always) peer-reviewed by like-minded scholars in the field

Closed system

Information is behind a paywall or requires a subscription

Critical thinking skills

Decision-making based on evaluating and critiquing information

Nonacademic information sources

Popular press information sources

Open system

Information that is publicly available and accessible

Research

The process of discovering new knowledge and investigating a topic from different points of view

Notes

1 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (n.d.). What is common knowledge? Academic integrity at MIT: A handbook for students. https://integrity.mit.edu/handbook/citing-your-sources/what-common-knowledge ↵

Attribution

Sections of this chapter were taken from Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers by Mike Caulfield (CC-BY).

Sections of this chapter were adapted from Speak up, Speak Out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking. ISBN: 13: 9781946135254 (CC BY-NC-SA)

Sections of this chapter were adapted from LIN 175: Information Literacy (CC-SA)

the process of discovering new knowledge and investigating a topic from different points of view

decision-making based on evaluating and critiquing information

Popular press information sources.

Peer-reviewed, published articles, journals, and sources

Open system describes information that is publicly available and accessible.

Information is behind a paywall or requires a subscription.

Fact-checking source claims by reading other sites and resources.

A written or spoken description of the elements (e.g. author, date, title) that uniquely identify a resource