Romantic Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Understand that relationships vary in duration, contact frequency, sharing, support, interaction variability, and goals.

- Distinguish romantic relationships from other kinds.

- Name several ways that attraction to another person happens.

- Define the five stages of Coming Together and the five stages of Coming Apart.

- Explain the strengths and weaknesses of stage models.

- Detail the critical constructs and conclusions of Uncertainty Reduction Theory, Relationship Maintenance Behaviors research, and Social Exchange Theory.

- Detail the critical constructs and conclusions of Communication Privacy Management, Relational Dialectics, and Genderlect Theory.

- Connect experiences of romantic relationships with each of Uncertainty Reduction Theory, Relationship Maintenance Behaviors research, Social Exchange Theory, Communication Privacy Management, Relational Dialectics, and Genderlect Theory.

- Realize the utility of developing scripts for dating and sex initiation.

- Recognize six love styles and their associated features.

Over the course of our lives, we will enter into and out of many relationships of several different kinds. Interpersonal communication scholars emphasize acquaintance, coworker, friend, family, and intimate/romantic relationships. According to a study conducted by OnePoll in conjunction with Evite, at any random time, the average American has:

- Three best friends

- Five good friends

- Eight people they like but don’t spend one-on-one time with

- 50 acquaintances

- 91 social media friends1

When it comes to dating, the average person has seven relationships before getting married.2 In this chapter, we focus on romantic relationships in particular though many of the concepts also apply to other relationship types. For instance, relational dialectics are featured here as well as in the chapter, Friendship Relationships. Relational stages, issues of privacy and disclosure, and the implications of gender and sex are certainly important to other kinds of relationships as well, but they may be best illustrated in the context of romantic ones.

Relationships may be instrumental as when a high school soccer coach and his sweeper back work together to win games and individually towards another league title and a college scholarship. Just about all relationships, however, feature social dimensions, as well. In them, we experience pleasure, companionship, control, and affection. You may spend time with one friend because you love talking to them and to another who can introduce you into popular cliques or desirable extracurricular activities. Relationships are generally meaningful and beneficial, allowing us to enjoy life, make important connections, and grow psychologically, emotionally, and physically. They can also be hollow sources of frustration, personal failure, and even regret and agony. Romantic relationships have great potential to produce positive and negative outcomes.

A major rationale for the study of interpersonal communication is that it is the primary means of engaging in relationships. A relationship is a connection or association between people that is marked by affiliation, attachment, and commitment. A romantic relationship is a union that features any or all of: affection, caregiving, shared relational identity, and intimacy in the form of emotional, intellectual, physical or sexual closeness. While some romances develop into marriages, which may be among the goals of many partners, the vast majority end in heartbreak.

Relationship Variables

All relationships are not the same. While they differ in value from treasured commitments to massive wastes of time, there are at least six characteristics that all relationships possess though to varying levels: duration, contact frequency, sharing, support, interaction variability, and goals.3

Some friendships last a lifetime, others last a short period. The length in time of a relationship is referred to as its duration. In a recent season of a reality show, one cast member spoke of his parents’ somewhat tumultuous thirty-year marriage while another agreed to marry a total stranger at first sight despite never having made it to a fourth date with anyone before.

Contact frequency is how often relational partners communicate with each other. Estranged siblings still have some form of relationship but they may only speak at each family gathering. Husband and wife real estate teams talk to each other every few minutes all day long, every day!

The more we spend time with other people and interact with them, the more we are likely sharingof details about ourselves. Sharing is the process of revealing and disclosing information about oneself to another. The extent of sharing of personal information is enhanced with trust and support of the relational partner.

The fourth variable is the amount of support provided within a relationship. Support is any message or behavior that conveys caring or comfort to another person so as to improve their condition. It could be the expertise or money that your Dad provides to get your car running again. It could also be the willingness of a stranger at a bus stop to listen to the impossibly vexing events of your day. One study found that married couples are more likely to provide supportive communication behaviors to their partners than are dating couples.4 An untold amount of research has demonstrated the benefits to our mood, health, and life experiences of having support of others, or even just believing that we do!

Your interaction variability with another person is the variety of interaction types you have and topics you cover. If Aunt Aaliyah only ever talks with Uncle Jayden about their retirement budget and his poor hygiene, they have low interaction variability. If it’s impossible to predict whether cousins Cho and Dae will be playing Atom Zombie Smasher together, serving as each other’s wingmen at the local nightclub, or physically tussling because of an argument about music, those two have pretty high interaction variability.

Relationship members almost always have goals or expectations and hopes for relational functions and outcomes. If your goal is to get closer to another person through communication, you might share your thoughts and feelings and expect the other person to do the same. If they do not, then you will probably feel like the goals in your relationship were not met because they didn’t share information. Romantic partners typically expect their significant others to be truthful, supportive, and faithful. Relational satisfaction will result if partners meet those expectations. Of course, satisfaction itself is a high-level relational goal and one that has bearing on how far relationships progress through recognized stages.

Exercises

- Think of two relationships you have in your life and which of them is more or less satisfying. Rate each of them for duration, contact frequency, sharing, support, interaction variability, and goals. Which of these variables seem to be especially important factors in your satisfaction?

Typical Progression of Romantic Relationships

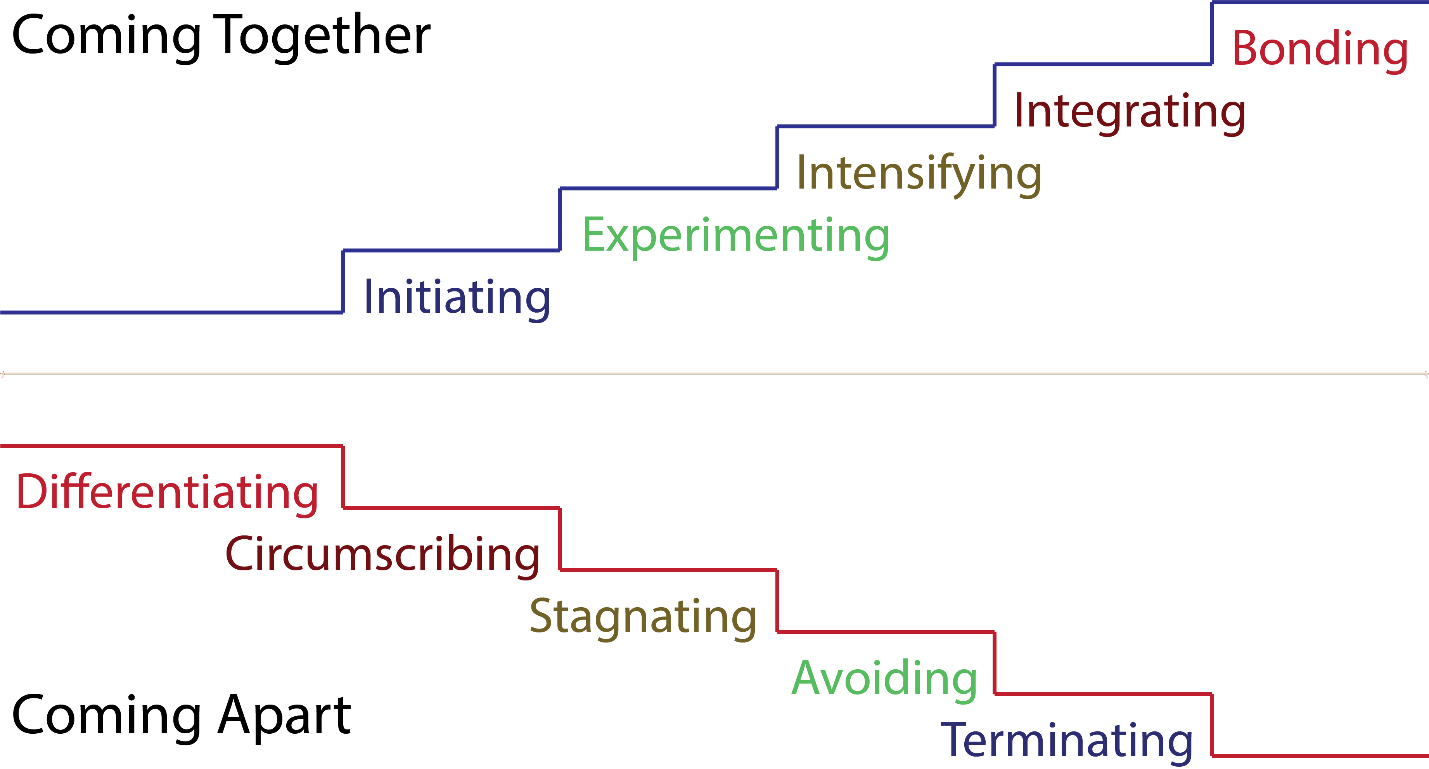

Mark Knapp introduced stages of relationship development5 and his model was later modified with coauthor Anita Vangelisti .6 Their Model of Interaction Stages in Relationships7 features ten stages that are categorized as either parts of the process, Coming Together, or parts of the process, Coming Apart. Some refer to this is as the staircase model (see Figure 2) of relational development.

While their stages, as described below, are highly informative and perhaps sometimes prescriptive for enjoying rich and full relationships, it is extremely important to realize the inherent dangers of fully embracing stage models.

Whether they model relationship development, grief, behavioral intervention, or group work, stages that represent human behavior cannot be precise or accurate in their linearity. Some stages may be skipped, some will overlap, and others may be revisited after subsequent stages have occurred. As long as we consider stage models to be descriptive rather than predictive, they can be very useful for understanding the experiences of human relationships from onset to expiration.

Knapp and Vangelisti’s ten stages6 can be applied to most types of relationships but are especially well-suited for our focus on romantic ones.

Coming Together

Do you remember when you first met a special someone in your life? How did your relationship start? How did you two become closer? Every relationship has to start somewhere and sometime.

In this section, we will learn about the coming together stages, which include: initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, and then bonding. But even before initiating, especially in the context of romantic relationships, as well as friendships, attraction is likely to play an important role. Attraction is a combination of interest in another person and a desire to get to know them better.

Researchers have identified three primary types of attraction: physical, social, and task. Physical attraction refers to the degree to which you find another person aesthetically pleasing, which can change greatly from one culture or era to the next. We also know that pop culture can greatly define what is considered to be physically appealing. Think of the curvaceous ideal of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor in the 1950s as compared to the thin Sydney Sweeney or Anne Hathaway. In the 1950s, you had solid men with “Dad bods” like Robert Mitchum and Marlon Brando as compared to the heavily muscled men of today like Joe Manganiello and Zac Efron. Research shows that males place more emphasis on appearance than do females.8

Social attraction, or the degree to which an individual sees another person as entertaining, intriguing, and/or fun to be around. Most of us are drawn more to people who are “the life of the party” as opposed to “a stick in the mud.” Task attraction occurs when we perceive that others possess specific knowledge, skills, and/or contacts that may help us accomplish specific goals.9

In addition to characteristics associated with the three types of attraction, proximity and the existence of similarities or differences can also play roles in determining with whom we initiate relationships. It is entirely common for romantic couples to trace their origin story to settings that they had in common. Proximity contributes when partners meet at work, the gym, the grocery store, or have a common circle of friends that introduce them.

People with similar cultural, ethnic, or religious backgrounds and characteristics are typically drawn to each other. The similarity thesis states that we tend to form relationships with others who are like us.9 There are three reasons why this may be: validation, predictability, and affiliation. First, it is validating to know that someone likes the same things that we do. It confirms and endorses what we believe. Second, when we are similar to another person, we can make predictions about what they will like and not like. We can make better estimations and have realistic expectations about what the person will do and how they will behave. We also feel affiliation, or connection, with others who seem like us. It can be thrilling to discover all the similarities shared with a potential relationship partner; who hasn’t stayed up most of the night finding out that this new person also likes Olivia Rodrigo and lobster roll and can’t stand movies with loud car chases and explosions?

However, in some cases, people feel a better match to those who are less like them. Differences between partners tend to benefit relationships when they are complementary, which means that their dissimilar characteristics fulfill each other’s needs. Introverts who prefer to talk less may prefer extroverts who like to talk more. An adept cook may cherish the opportunity to feed an appreciative partner who barely manages to add milk to cereal. However, differences can lead to problems in relationships as when a free spender is resented by a frugal budgeter or the sloppy are paired with the fastidiously tidy.

Initiating

Once attraction has been established, the five stages of Coming Together may begin. Having determined that you are willing to take the risk and expend the effort of approaching a potential partner, you must let them know of your interest in initiating a conversation.

The initiating stage is the first one, when making contact and signaling interest are the goals. Eduardo says hello and introduces himself to Karina, who makes sure to indicate her receptivity by smiling and touching his arm. In this earliest of relational stages, they are primarily interested in making contact. Conversation may be superficial and not very personal; this squares with Uncertainty Reduction Theory, which is introduced in the next section of this chapter.

Experimenting

After we have initiated communication with the other person, we go to the next stage, experimenting, when “small talk” happens and commonalities are discovered. At this stage, Eduardo and Karina begin considering whether they wish to continue the relationship by learning more about the other person. Multiple interactions tend to be casual and reveal hometowns, favorite colors and subjects and pet peeves. Thoughts about forming an actual relationship preoccupy; Karina considers whether she can tolerate Eduardo’s smoking habit while embracing his charitable nature. For now, members of recent generations might describe the relationship as one of “talking.”

Intensifying

The intensifying stage features establishment of identity as knowledge about partners increases greatly. Conversations become more serious and interactions more meaningful. Eduardo may begin to consider Karina to be his girlfriend, or they may mutually agree that they are now “dating” or “seeing each other.” Both are becoming more serious about their relationship.

Integrating

As a couple achieves deeper levels of expectations and commitment, perhaps including exclusivity, and tells others about the relationship, they are inhabiting the integrating stage. The amount of time spent together grows as do assumptions about participating in many activities together. Individuals now think of themselves as a unit.

Part of the appeal of the reality show, Married At First Sight, comes with observing couples who are so blatantly mixing up these stages of relationships by getting married at their first introduction to each other. Nevertheless, a great example of the integrating stage emerged. In Season 16 of MAFS, Shaquille takes great exception to Kirsten not offering to accompany him on his business trips as a college recruiter. Her failure to meet his expectation of this act of integration becomes a very large sticking point as Shaquille considers whether to pursue a divorce at the season finale.

Bonding

The final stage of Coming Together is bonding, when commitment is increased and announced to wider social networks. In the case of couples on the path to marriage, this might include the proposal and engagement. For many traditional couples, relationships with partners’ families have already started but now the ties are drawing tighter. Karina and Eduardo actually got eloped and married before making the announcement of that ultimate commitment to everyone they know!

In the circumstance of marriage, it is not like the relationship is done growing. As landmarks and milestones like anniversaries, child birth, and renewal of vows pass, integrating and bonding are addressed and experienced again. In fact, a void in the stages approach appears here as many relationships are maintained for years and years before coming apart, and some never do. The next section of this chapter reviews some of the interpersonal communication scholarship about relational maintenance.

Nevertheless, what separates Knapp and Vangelisti’s first and last five stages is some dividing line between Coming Together and Coming Apart.

Coming Apart

Some couples can stay longterm in committed and wonderful relationships, even if faced with individual or collective turmoil. For others, however, things inevitably come apart. No matter how hard they try to stay together, tension, resentment, and mistrust may foil those efforts. These ill-fated couples go through a Coming Apart process that involves: differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, and terminating.

Differentiating

The differentiating stage is when the parties start to disengage with their identity as a couple in favor of their own. Independence begins to outstrip interdependence. Differences become over-emphasized while commonalities are overlooked. Language may start to change from “our car” and “our child” to “my car” and “my child.” Tensions become harder to resolve, partly because they are associated with others from the past. These are early signals that the relationship is coming apart.

All photos and videos on Pexels are free to download and use; Attribution is not required.

Circumscribing

Circumscribing is the stage when partners strive to limit their interactions with each other. Communication will lessen in quality and quantity. Taboo topics are avoided to prevent arguments. Less time spent together and fewer displays of affection and intimacy are exhibited.

Stagnating

The next stage is stagnating, which means the relationship is not improving or growing. Limited communication becomes restrained, if not downright awkward. The partners may still live with each other physically but an emotional inertia prevents attempts to rebuild the relationship, which has become a chore. The couple is approaching the point of no return, where odds for reconciliation are becoming remote.

Avoiding

When a couple prefers to stay away from each other entirely rather than interact or communicate, they have reached the avoiding stage. As partners have no desire to see or speak to each other, physically moving out of the shared residence becomes increasingly likely. Sadness is at its height as mourning for the relationship has started.

Terminating

The terminating stage is when the parties end the relationship, gradually or suddenly, and make arrangements for life post-relationship. Awareness of interpersonal communication has popularized a focus on the channels (e.g., text message, email, Facebook posting, face-to-face) utilized for “breaking up” and their varied effects.

Final Caveat On Stage Models

Knapp and Vangelisti’s is not the only approach to mapping relational life cycles. For instance, fellow scholar and theorist Steve Duck proposes four phases of relationship dissolution: the intrapsychic (i.e., dissatisfaction emerges for at least one of the partners), dyadic (i.e., discontent transforms from a private cognition to a shared impression), social (i.e., relational conflict goes public with family and friends) and grave-dressing (i.e., the relationship ends and narratives about reasons are created) phases.10

It bears repeating that stage models do not, nor do they intend to, perfectly portray the progression of every romantic relationship. Not every one goes through each of the ten stages; some terminate before the experimenting stage is complete. Some relationships coast smoothly after the intensifying or bonding stages without ever Coming Apart. Even after a period of stabilization, maintenance, and satisfaction, movement in either direction through more stages is possible.

Moreover, communication technology, terminology, and dating practices of contemporary couples may create more distance between reality and stage models. The stages do a poor job representing “talking,” “hooking up” or having “friends with benefits.” Relationships may also take place primarily, or even solely, in digital space.

Still, the ten stages of Coming Together and Coming Apart map pretty well to many romantic couples. Critically, they also provide description and recognition of phenomena that many dating partners identify, and with which they need understanding and assistance to best navigate.

Key Takeaways

- Attraction comes in physical, social, and task forms and may also be inspired by proximity, similarities, and even differences.

- Knapp and Vangelisti’s model recognizes five stages of Coming Together and five stages of Coming Apart.

- The Coming Together stages include: initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, and bonding.

- The Coming Apart stages include: differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, and terminating.

- Care should be taken not to subscribe to stage models strictly; human behavior is rarely that linear or predictable.

Exercises

- Ask couples that you know how they started and determine the role of proximity in their meeting.

- Which of the five stages of Coming Together have you most clearly experienced in your romantic history?

- Which of the five stages of Coming Apart have you most clearly experienced in your romantic history?

Interpersonal Communication Theory and Romantic Relationships

Theories Tied to Relationship Progression

Interpersonal communication theory is a source of vast knowledge and guidance for anyone who relates with others, no matter their experience or success levels of the past. Several interpersonal communication theories may be considered to be most relevant to earlier or later stages of relational development, which is not to say they don’t pertain to other times in relationships, too.

Dealing with uncertainty is a prominent aspect on the front end of most romantic relationships. Working to maintain relationships mosly occurs between their beginnings and endings, while gauging and contrasting their costs and benefits may inform decisions about whether to terminate them.

This section provides short summaries of concepts found, and communication’s roles, in each of Uncertainty Reduction Theory, Behaviors of Relational Maintenance, and Social Exchange Theory.

Uncertainty Reduction Theory

Harboring an interest in communication as it takes place early in relationships, Charles Berger and Richard Calabrese began fleshing out their Initial Interaction Theory in the early 1970s. One phenomenon figured so prominently in their work that it was soon centered in the revamped Uncertainty Reduction Theory.11 They began to understand that early in relationships, even as soon as the very first interaction, the participants experience, and react to, the unpleasant sensation of uncertainty.

Picture yourself on the first day at your college or university. Chances are good you moved into a residence like a dorm, before classes started, and were thrust into a variety of orientation activities. This was probably marked by the meeting of many new people in a short period of time. Every one of those people you met that day, or any other, were initially strangers to you.

The word, “stranger” originates in the French, “estrangier,” which transaltes to foreigner or alien. To each of us, strangers are strange. We know nothing about them, save what we immediately observe. Are they experienced or novices like us? Do they give of themselves freely to those they don’t know? And who exactly are they, anyway? What are they here for, what do they want? Could they be dangerous? Should I stay away from them?

These and hundreds of other questions we ask ourselves about new people are initially unanswered. We are so far from certain about them; in fact, we are quite uncertain. And we don’t like it.

Berger and Calabrese called uncertainty an aversive state, one based in our lack of knowledge about something, like a place or event, or someone, like Jacques, the Canadian first-year student who wore a hockey sweater on the first day of orientation, which was about 95°.

Because we don’t know much of anything about others in our first few meetings with them, we are usually quite uncomfortable. We don’t know whether they prefer Mike or Michael, we don’t know whether they like to kid around, we don’t know whether a political remark will send them off the deep end. Uncertainty, excuse our French, sorta sucks.

So, we are motivated to reduce the uncertainty inherent in these situations. Finding out more about this poorly known person, gathering information, thus increasing our certainty (i.e., reducing our uncertainty) about them is the only route for making ourselves feel better about interactying with them now or in the near future.

In fact, if we think we will see them again, we will really want to to find out more. Berger and Calabrese nominated three conditions that are likely to supercharge our quest to discover information. The first is anticipation of future interaction. Jacques apparently lives next door to you now so you might as well start figuring him out. The business dude in the big brimmed classes, humming to himself on an elevator in a building that you won’t revisit, is a much less worthy target of investigation.

All photos and videos on Pexels are free to download and use; Attribution is not required.

However, if that business dude sports a Google logo conference badge and you would do anything to get your resume noticed by that company, you might have what the theorists called, incentive value. Get to know this guy a little and maybe you can get your foot in the door! From the romantic perspective, maybe you find yourselves attracted to the new person (i.e., they’re hot!) and your incentive is to pursue them for purposes of physical intimacy.

Finally, Berger and Calabrese predicted that deviance , behavior that is unexpected or out of place, can serve as a motivational boost to reduce uncertainty. If he goes from humming on the elevator to belting out the theme song, “Hello, Dolly!” while performing a little soft shoe dance routine, you probably become extremely curious about what makes this guy tick (unless, the deviance from expected behavior is so severe that you lose all motivation to be around, or know, the stranger at all).

So if uncertainty is discomfiting and we are driven to counteract it with some information, how do we go about doing that?

The first strategy is the passive one, where we merely observe all we can about the target’s appearance and behavior. The second is active, where we ask around about them or perform our own furtive investigation, perhaps on social media. And the third is interactive, where we actually engage the individual in our mission to learn about them.

Utilizing face-to-face conversation, there are three well-recognized tactics. One is to just ask them questions. You can inquire about their name, their age, where they live, what they study or do for a living, or even whether they are a regular here where you’ve met them.

A barrage of questions is not always the most pleasant way to interact, however. Another tactic is to offer information about yourself, in hopes that they will match you with some about themselves. The superficial level of the questions, and the information disclosed, at this early point in the relationship are very much the stuff of Social Penetration Theory, covered in the Talking and Listening chapter.

Lastly, we can hazard guesses about them and allow them to confirm or invalidate them:

“I hear that accent of yours, I bet you’re a Red Sox fan.”

“No, my Dad was from Long Island and we’re actually generational Yankee fans.”

“Do you all get to go back to New York? I’ve always wanted to go.”

And the race to reduce uncertainty is officially underway! Especially in the early stages of relationships, the reduction of uncertainty drives much of our communication.

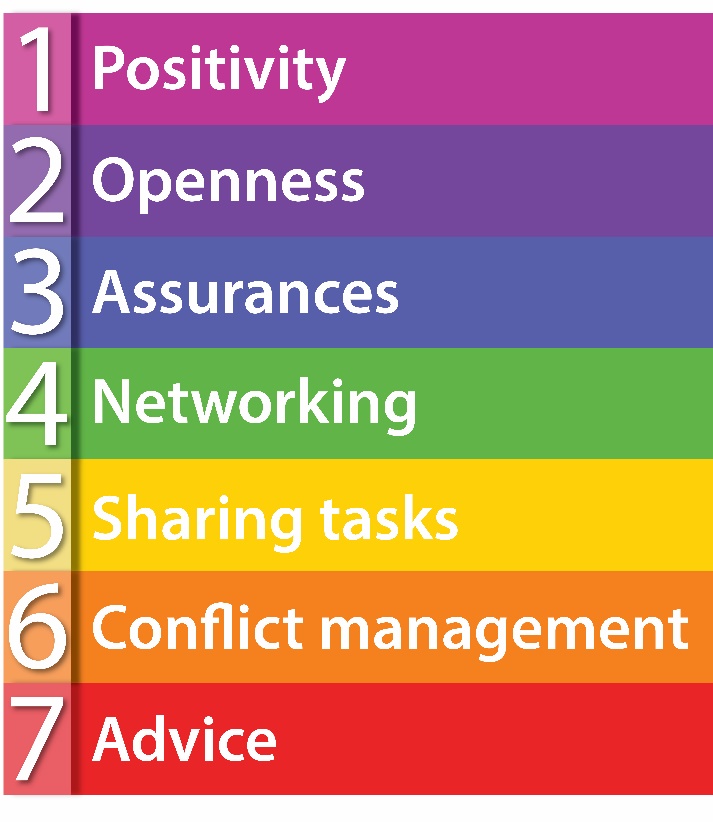

Relationship Maintenance Behaviors

You may have heard that relationships are hard work. Relationships need maintenance and care. Just like your body needs food and your car needs gasoline, your relationships need attention. Relationship maintenance lasts from the first to last interaction episodes between partners. It consists of the behaviors and strategies that enable the stabilization point between relationship initiation and potential relationship destruction.12

Daniel Canary and Laura Stafford stated that “most people desire long-term, stable, and satisfying relationships”13 and that relationship maintenance behaviors are required to achieve them. They believed that relationships do not just “fall apart or happen to stay together.”13

Joe Ayres studied how individuals maintain their interpersonal relationships.14 He discovered that relational intent determined effort; partners that really want to stay together are more likely to employ the three maintenance strategies he identified.

First, avoidance strategies are used to evade communication that might threaten the relationship. Laura may just deal with figuring out how to pay the monthly bills rather than bring up how her girlfriend Iris is spending way too much lately. Balance strategies are used to maintain equality in the relationship so that partners do not feel underbenefited or overbenefited from being in the relationship.14 Iris makes sure to do some house cleaning on the weekends as Laura is stuck with many household chores during the week. Finally, direct strategies are used to evaluate and remind the partner of relationship objectives. Laura will occasionally try to refresh Iris’ desire to save up enough together to achieve their house buying dream.

Canary and Stafford promote five key relationship maintenance behaviors. First, communicating with positivity is a critical relational maintenance factor as being nice results in romantic partners feeling happy and supported.

Second, openness is the degree to which partners disclose and share information and feelings. Third, assurances are words that emphasize the partners’ commitment to the duration of the relationship. Fourth, networking is communicating with family and friends. Lastly, sharing tasks is doing work or household tasks together or dividing them fairly. Later, Canary and his colleagues found two more important relationship maintenance behaviors: effectively managing conflict and providing advice.15

Positivity’s prominent placement among these behaviors is substantiated by a famous premise, founded in the relational research program of John Gottman. Along with colleague Robert Levenson, Gottman determined that16 partners in satisfying relationships provide a ratio of five positive behaviors or comments for every single negative one. So, if Tennley wants to make sure her relationship with Jimmie is satisfying, for every harsh criticism or sarcastic aside she throws at him, there should be some humor, a few acts of affection, a compliment, and an unsolicited favor.

Finally, in a series of studies originally intended to compare Canary and Stafford’s manitenance behaviors as enacted in computer-mediated as opposed to face-to-face interactions, Andrew Ledbetter found that participants in everyday relationships reported much more specific behaviors. These included: sharing possessions, sharing entertainment media experiences, spending time together, casual conversation as well as deeper talks, both verbal and physical expressions of affection, sharing responsibility for tasks, managing and recovering from conflict, being humorous, and engaging in shared networks of family and friends.17 The eleven behaviors may not be the perfect recipe for keeping love alive but they sure seem incredibly advantageous for long-term couples.

Social Exchange Theory

Maggie is growing increasingly exasperated with her boyfriend, Gunnar. When he approached her at a school-sponsored dance two years ago, she could not have been more elated. She considered herself to be “bookish and a little mousy, to be honest” while Gunnar was the star of the drama club’s presentations of Our Town and Mamma Mia. Maggie remembered a slumber party sleepover where her girlfriends spoke in awe about the shine that came off his teeth on stage.

The couple has been together exclusively ever since. However, in the last few weeks alone, Maggie has bailed Gunnar out after a charge of DUI, tended to the wounds he suffered in a bar brawl, disputed rumors that he impregnated a sophomore from the next town over, and fought to get her credit card charges expunged when he took her Visa on a solo vacation.

For all the affection she enjoys from him and attention the popular girls give him as his main squeeze, Maggie is wondering whether the relationship is worth it anymore. Her process of considering a break up with Gunnar is an ideal example of John Thibaut and Harold Kelley’s Social Exchange Theory.18, 19

Social Exchange Theory adopts an economic orientation to relationship evaluation. Thibaut and Kelley believed that we, perhaps not completely consciously, engage in cost-benefit analysis as we consider relationships we are engaged in. The rewards of being in romantic relationships are many: security, companionship, sex, love, support, and status. Some also garner material benefits from their relationships like living in a better house and neigborhood or buying fancier clothes and better cars.

But relationships may cost us quite a bit as well. We may find ourselves lacking free time, independence, the excitement of single life and responsibilities like supporting and caregiving our partners through times of illness, grief, job loss, etc. Our partners may drain us of energy, time, passion, money, or other resources.

Partners who find that the pleasurable aspects of a romantic relationship compensate for, or outstrip, the associated downsides are likely to wish to continue. Conversely those who feel the expense, worry, arguing and resentment are outweighing the rewards may start to lose interest in continuing the relationship and allow, or inspire, the onset of stages of Coming Apart.

Though such economic assessment can occur no matter how young a relationship is, it may be fair to regard Social Exchange Theory as most related to the latter stages. This is because by its nature, Social Exchange may help to predict or explain the reasons that relationships breakup and end.

Thibaut and Kelley operationalize this balancing of the emotional ledger with a concept they call the comparison level(CL), which is the minimum standard for satisfaction that a relational partner is willing to tolerate. When Maggie, having summed the positives and the negatives, figures out what her own satisfaction level is in her relationship with Gunnar, she compares that to her CL. If the CL is exceeded, she is likely to remain commited to the relationship but if the CL is higher, Maggie may opt out.

We should note that we each have our own CL; that is, our standards vary for how much relational satisfaction is enough. A major determinant of anyone’s CL is probably the quality of their prior, perhaps recent, relationships. If you had a history of really bad relationships, you might be content now with a mediocre one, for instance.

Costs and rewards are not the only factors used to review the worth of a romantic relationship. Social Exhange Theory accounts for the incorporation of alternatives to the relationship. Thibaut and Kelley established the comparison level of alternatives (CLalt), as a threshold for satisfaction in a relationship determined by available alternative arrangements. If Gunnar has a bevy of beauties lined up and ready to take Maggie’s place, his relationship with her is going to have to provide a very high level of satisfaction for him to stay interested.

A perfect embodiment of the CLalt is an image that just about all of us are familiar with. The distracted boyfriend meme is a street scene where a young couple has just passed an attractive girl in a red dress. The boyfriend, clad in his blue plaid shirt, has turned his head all the way around to look at her more, with an admiring expression on his face. His girlfriend peers up at him, astonished and disgusted by his interest and his lack of respect for her. The image has been circulated throughout the Internet with a variety of labels applied to the characters like Charles Barkley for the guy, MVP Trophy for the girlfriend, and World Championship for the girl in the dress.

For our purposes, the passing girl is perhaps directly raising this guy’s CLalt as well as the ire of his girlfriend. Who knows? Perhaps his wandering eye has just tipped the scale in the favor of disadvantages his girlfriend considers whether to continue their romance!

Theories Relevant Throughout Relationships

Whereas theories about uncertainty reduction, maintenance behaviors, and social exchange apply to any phase of a romantic relationship, they map particularly well to the early, middle, and later stages, respectively. Communication Privacy Management, Relational Dialectics, and Genderlect theories are evergreen for all phases of relationships, just as likely to come into play at any given point. We are always determining which secrets to share with whom, how to get all that we want out of our relationships, and how to best communicate and relate with people of other sexes or genders.

Communication Privacy Management

Sandra Petronio is another communication scholar who has renamed her theory to better reflect how it has developed. Communication Boundary Management Theory20 has been rebranded as Communication Privacy Management (CPM) Theory21 since the 1990s. Though disclosure is treated more holistically in our Talking and Listening chapter, CPM deserves its placement here as it explains one of the chief sources of tension in romantic relationships.

Petronio contends that issues of information ownership, sharing secrets, and regulating rules for doing it are vital components of romantic relationships. Privacy boundaries are symbolically placed between personal private information and details that are shared with others. Individuals establish rules for who they share this information with and why. Rules are also inherently understood by, or expressed to, the receivers of private information as to who else is privy to the shared information. Anyone who receives the information is then said to co-own it.

Critically, when privacy rules are broken, a condition Petronio calls boundary turbulence, relational chaos may ensue.

So, Savannah is torn about whether to share an embarassing and distressing part of her history with Andrés, her fiancé of eighteen months. From eleven to seventeen years of age, Savannah struggled mightily with body image, believing that she was too overweight to be attractive or at times, to even show herself in public.

She developed anorexia nervosa and made a practice of no more than two bites of food per sitting. This meant she seldom ate with friends or family which only heightened her feelings of isolation and worthlessness. When her weight loss made no difference in how she felt about her body, she became despondent to the point of considering self-harm. Thankfully, a concerned guidance counselor elicited this information from Savannah and helped her enter therapy and treatment that returned her to a lifestyle similar to her peers.

Savannah is terrified that Andrés will leave her when he learns of her past behavior, which she now considers to be embarrassing. She decides that he deserves to know about it and “what he is getting himself into.” Her boundary for this issue is that no one else besides her most intimate partner should ever hear about it.

Andrés receives the story quite well and assures Savannah that no one should be ashamed of their past if they have made progress in their lives. “After all,” he tells her, “everything that you have ever gone through has contributed to the amazing, sexy, brilliant, vital person you are today!”

Savannah is thrilled with his reaction but explicitly sets the privacy rule that he must never tell anyone in his family, even though they are a close-knit and honest group. She didn’t feel the need to demand that he not tell anyone else because he is obviously sensitive enough to know that this secret is not for public consumption. This reliance on an implicit rule is where they run into trouble.

A few weeks later, Andrés casually mentions that he reassured a salesperson at work that they could overcome their eating disorder just as his fiancé had. Savannah was instantly enraged with him both for revealing her secret to a complete stranger to her and also to someone who she might someday have to face. Andrés is bewildered as he felt he had followed her instructions perfectly as he never told anyone in his family.

As you might imagine, this boundary turbulence was extremely difficult for the young couple to work through. She still loved him but was now doubting his judgment and her trust in him. They finally were able to move on with their plans to marry after resolving that explicit communication was necessary in matters of such importance.

Relational Dialectics

The construct of dialectics has been recognized by many scholars for many years. They are opposing forces that create everyday experiences of feeling pushed and pulled at the same time.

Leslie Baxter is a scholar who has always been interested in the challenges presented by relationships and the use of communication, or dialogue as her academic idol Mikhail Baktin referred to it, to navigate them. Early in Baxter’s career her colleagues were interested in relational beginnings and disclosure, while she gravitated more towards relationship termination and decisions NOT to disclose made in relationships. The seeds of her Relational Dialectics can be found in these conditions of antithesis.

In 1996, with Barbara Montgomery, Baxter oublished the book, Relating: Dialogues and Dialectics.22 It reported research about dialectical tensions in families, romantic relationships, and friendships. Their overarching research premise is that all personal ties and relationships are always in a state of constant flux and contradiction. Specifically, relational dialectics form a “dynamic knot of contradictions in personal relationships; an unceasing interplay between contrary or opposing tendencies.”23

Relational dialectics form contradictions that are co-existing and must be met with a “both/and” approach as opposed to an“either/or” mindset. For each of the three famous oppositional dialectics, the more relational partners have of one, the less they have of the other. Where both or either (!) parties prefer to be on the spectrum between the two poles can be another matter entirely. Each of these realities assures that the navigation of dialectics in relatioships, especially romantic ones, is a never-ending, ever-changing process of communication and adjustment.

Though others (e.g., Ideal-Real, Similar-Different, Accepting-Critical) have been identified, the three most often covered in academic journal articles and textbook chapters are Integration-Separation, Stability-Change, and Openness-Closedness. Sometimes, synonyms are used for any of the dialectical poles but these terms represent the essence of the Big Three.

Integration-Separation

Within the dialectic of Integration-Separation, partners seek intimacy, closeness and commitment, but also desire their own identity, space, and time. As great as it is to have someone who will be there always, to go to movies with and eat dinner together, raise a family and spend the holidays, it also feels necessary to see friends on your own, have your own hobbies, and have quiet time at home. James loves watching romantic comedies with his wife, Michele, in their home theatre, but if he had to do it every night, he couldn’t spend the alone time he craves with his comic book collection and his online gaming community. She could not imagine James joining her book club but looks so forward to making dinner together in their kitchen most nights.

Stability–Change

One of the nicest benefits of being in a romantic relationship is the stability it provides. Your partner is probably dependable and can be counted on to be the one that makes the bed or calls the cable company whenever there is a service outage. You don’t have to experience the ridiculous highs but also numerous lows of traversing the dating scene. If there is a family funeral or wedding, there your partner will be, at your side. Families of Italian descent in East Coast locations such as New Jersey and Long Island are notorious for traditions like Wednesday Pizza Night and Saturdays being for steak and pasta; the reliability of these rituals can be incredibly comfortable and pleasant.

On the other hand, sameness can be stagnant and boring. If Lois and Alonzo institute a set schedule for sex, though they can count on that and are happy to make it a priority, the absolute regularness of that can make it mundane rather than exciting. While we enjoy attending our partner’s company holiday party every year, it is the same location and same people each time. Wouldn’t it be fun to just skip it and jet off to the tropics just once instead? For as much as routine and steadiness are wonderful aspects of long-term relationships, if they preclude change and prevent growth, the lack of novelty may foster dissatisfaction should follow.

Expression-Privacy

It is pretty easy to find information about, and encouragement of self disclosure in this book. The Talking and Listening chapter includes Social Penetration Theory in which the act of disclosing to others is celebrated as the essence of intimacy. Indeed, one reason we cherish our romantic partners is that they are sounding boards for all of our experiences, feelings, and secrets. It is so much easier when you have someone to complain to about the cubicle inhabitant at work who insists on eating her tuna salad at her desk or to share your excitement with about an impending promotion. We also appreciate being the confidante, the person our beloved will share with, in kind.

Conversely, there should be some measure of privacy in our relationships, too. Our significant other doesn’t need to know every thought or sensation we have. Memories of a prior lover, your parents’ original doubts about them, and the contents of your middle school journal might very well be things that you want to protect even from “your person.”

If you are sensing similarity between the openess-closedness dialectic and Communication Privacy Management, welcome to the wonderful world of communication theory where insightful perspectives about the human condition sometimes overlap in fascinating ways!

Relational dialectics as a theory is a treatment of disparities that emerge with consideration of the continuums between integration and separation, stability and change, and openness and closedness. One source of the disparity is between the desired and the actual. If you would like to be on your own about 35-40% of your waking hours but your spouse is nearby nearly every single minute, that is a challenging difference. Such difficulty can be magnified by the potential of disparity between partners’ preferences like if one is a risk and novelty seeker while the other is a secure homebody. Finally, each of us changes over time. My partner may be confused when my previous willingness to listen to every detail of her girlfriends’ drama transforms to a position of not wanting to know everything that she experiences.

One of Baxter’s core premises is that dialogue, or communication, is the route to shoring up some of these relational fissures. If you feel your partner has pulled away too much, devoting ever more time to their work or sports, talk to them about it. If they are irked that you have been going through their text messages and DMs, they should talk to you about it. Through conversation, negotiation, and compromise, the resolutions of dialectical discrepancies and outcomes of romantic relationships, are most likely to be satisfying.

Genderlect

The terms sex and gender are often used interchangeably though they shouldn’t be. Sex refers to a person’s biological status as male or female, as determined by chromosomes and secondary sex characteristics. It is mainly treated as a binary variable. Gender, however, refers to the behaviors and traits society considers masculine and feminine.24 It is fluid, can vary in many different ways, and includes more than two possible values (e.g., masculine, feminine, androgynous). Ironically, one of the first theories about differences between the sexes in communication adopted the term gender and was called genderlect.

Sex Differences in Interpersonal Communication

In the United States, we have expectations for how males and females should communicate and behave.25 We learn sex differences at a very young age. Boys and girls are socialized to play, perform, dress, and respond to things differently by families, mass media, in school and on the playground.

A popular theory that explores sex differences is Deborah Tannen’s genderlect theory. It essentially represents the idea that men and women are so different and have such different interactional and communication approaches and purposes, it is as though they were raised in different cultures. In fact, most were raised differently in the same culture but Tannen points out they almost speak and relate in different versions of the same languages. This is how she derived the term genderlect. The theory predicts tremendous struggles in communicating with the other sex that can only be overcome with specialized scrutiny and adaptation.

In her book, You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation, Tannen describes how men prefer “report” talk that is task-oriented and women engage in “rapport” talk, where the purpose is to develop relationships and emotional connections.26 Men are more competitive, especially in public settings and make themselves the heroes in their own stories while women are more collegial and downplay their individual roles and contributions. Women want to explore feelings with their male romantic partners but they prefer to avoid such discussion. Men want to keep things straightforward and deal with relational issues in pragmatic, rational tones.

Genderlect and the different cultures thesis have come under critical scrutiny, A pre-eminent scholar of sex-related differences and similarities, Kathryn Dindia, has pored over huge literatures of related studies and concludes, “sex differences exist but they are overwhelmed by similarities. When there are differences in general they are small.”27 For instance, some studies find a lack of significant difference between the sexes. Others find significant differences but with small effect sizes which means they were not as pronounced as they could be. And critically, these studies usually represent samples where something like 85% of the men and women overlap in their scores and the differences reside in only the remaining 15%. In fairness, some larger differences were found to exist in the ways that males and females express themselves nonverbally.

One excellent and specific refutation of the genderlect/different cultures theory came when a University of Kansas professor of Communication Studies, Adrianne Kunkel, and her advisor at Purdue University, Brant Burleson, tested whether males and females had different preferences for how they are offered comfort when upset. Unlike what genderlect would predict, men and women both desired emotional support such as talking it out more than instrumental support such as helping to fix a problem.28

Of course, the prospect of ALL men behaving one way and ALL women behaving another is intuitively doubtful. Maybe the most important caution against subscribing fully to the predominance of differences between the sexes is that the binary division of the world into males and females is becoming less acceptable. Gender is growing as the sex adjacent identity that most people now prefer to report.

Key Takeaways

- Uncertainty Reduction Theory poses communication tactics such as questioning and disclosure for getting to know new people better, which makes us feel better.

- A variety of behaviors are associated with successful relationship maintenance These include, but are not limited to: positivity, openness, expression of affection, and time spent together and with family and friends.

- Social Exchange Theory predicts that motivation to continue romantic relationships hinges on cost-benefit analysis and comparison to a minimum level standard of satisfaction or to available alternatives.

- Communication Privacy Management examines private information, our decisions about who to share it with, and rules for who they are allowed to share it with.

- Relational dialectics are contradictory desires within relationship, such as integration vs. separation, stability vs change, and expression vs. privacy.

- Genderlect theory, which represents men and women as so consistently different that they must adjust communication greatly in order to get along, has received less support in recent years.

Exercises

- Which of the relationship maintenance strategies do you identify as having employed in your own romantic experiences? Find a peer and compare your answers.

- Do you think your preferences lean more towards one side than the other in each of the integration vs. separation, stability vs change, and expression vs. privacy dialectics. Why do you think so?

- What is an example of private information that you were willing to share with one person but not with another?

Dating Scripts and Love Styles

We talk of dating as a single construct a lot of the time without really thinking through how dating has changed over time. In the twentieth century alone, we saw dating go from a highly formalized structure involving calling cards and sitting rooms, to drive-in movies shared in a car, to online dating with people we’ve never met in real life.29 The 21st Century has already changed how people date through social networking sites and geolocation dating apps on smartphones. Social trends have moved away from terms like “going steady” and towards “talking” or “hooking up.” Dating is not a single thing, and dating has definitely changed with the times.

Paul Mongeau, Janet Jacobsen, and Carolyn Donnerstein presented five “supracategories” for what constitutes a “date”.30 First, dating involves specific communication expectations. For example, people expect that their dating partner will be polite, relaxed, and social. Second, dating involves specific goals, like exploring a romantic relationship or just having fun. Third, specific date elements include getting ready, meeting somewhere, and engaging in shared activity. Fourth, dates are dyadic and couple-based, even when they are embedded in larger “group dates,” Last, dates involve feeling states which may include attraction and affection.30

Online matching service Match.com publishes an annual study examining single dating life and has recently found the following about their respondents:

- 48.9% have created at least one profile on a dating website or app.

- 41.1% have dated someone they met online.

- 25.1% have a “checklist” when it comes to finding a long-term romantic partner.

- 83.5% believe that love is hard to find in today’s world.

- 38.1% have been in a “friends with benefits” relationship.

- 28.3% had a friendship that turned into a significant romantic relationship.31

As dating appears to still be a significant feature of romantic relationship pursuit, it follows that many people have specific ideas for how dating works.

Dating Scripts

Robert Abelson originally proposed the idea of script theory back in the late 1970s.32 He defined a script as a “coherent sequence of events expected by the individual, involving him as either a participant or an observer.”32 According to script theory, people tend to pattern their responses and behaviors during different social interactions, which requires being able to imagine past, present, and future behaviors and developing a script of expectations.33

In 1993, Suzanna Rose and Irene Frieze derived two different scripts for dating based on the reports of their heterosexual male and female college student sample. The male script consisted of 15 different behavioral actions, all initiated by the male:34

- Picked up date

- Met parents/roommates

- Left

- Picked up friends

- Confirm plans

- Talked, joked, laughed

- Went to movies, show, party

- Ate

- Drank alcohol

- Initiated sexual contact

- Made out

- Took date home

- Asked for another date

- Kissed goodnight

- Went home

The female script, contained behaviors exhibited by both parties on a date: 34

- Groomed and dressed

- Was nervous

- Picked up date (male)

- Introduced to parents, etc.

- Courtly behavior (open doors–male)

- Left

- Confirmed plans

- Got to know & evaluate date

- Talked, joked, laughed

- Enjoyed date

- Went to movies, show, party

- Ate

- Drank alcohol

- Talked to friends

- Had something go wrong

- Took date home (male)

- Asked for another date (male)

- Told date will call her (male)

- Kissed date goodnight (male)

Take a second and go through these two lists. How do you think they differ? How well might they apply among today’s heterosexual couples? One year after Rose and Frieze’s study, Dean Klinkenberg developed scripts for gay male and lesbian dates.35 Would you guess that they differed from Rose and Frieze’s and from each other?

We’ve all been conditioned since we were very young to date and how to do it. We’ve listened to adults tell stories, watched dating as it is fictionalized on television and in movies, experienced it ourselves, and shared notes with friends. Thankfully, because there are cultural images of dating presented to us, our dating partners are likely to have similar dating scripts to ours, as long as they are from the same, or a similar, culture.

Research Spotlight

One area that has received a decent amount of attention in script theory is sexual scripts, or scripts people engage in when thinking about “who can participate, what the participants should do (i.e., what verbal and nonverbal behaviors should be included and in what order they should be used), and where the sexual episode should take place.”36 In 1993, Timothy Edgar and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick proposed a sexual script theory for communication.37 In 2010, Betty La France examined reactions to the following scripts for public and private verbal and nonverbal communication behaviors that lead to sex:

One area that has received a decent amount of attention in script theory is sexual scripts, or scripts people engage in when thinking about “who can participate, what the participants should do (i.e., what verbal and nonverbal behaviors should be included and in what order they should be used), and where the sexual episode should take place.”36 In 1993, Timothy Edgar and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick proposed a sexual script theory for communication.37 In 2010, Betty La France examined reactions to the following scripts for public and private verbal and nonverbal communication behaviors that lead to sex:

| Public Setting Script | Private Setting Script (Her Apartment) |

|---|---|

| Craig was standing at the bar when he noticed Sarah. She also noticed him. There was eye contact between them. She glanced away. He approached her. “Hi, my name is Craig,” he said. “I’m Sarah. How are you doing?,” she replied. “Can I buy you a drink?,” he asked. Craig asked, “Are you alone?” “No, I came with some friends,” she replied. Craig asked her questions about herself, such as where she was from and what her major was. She responded to his questions. In return, Sarah asked Craig similar questions about himself. |

She brought him a drink. “Want to listen to some music?,” asked Sarah. She put on the music. Craig asked, “Are your roommates around?” “This is a great apartment,” said Craig. He sat next to her on the couch. They engaged in casual conversation. There was eye contact between them. He moved closer to her. “You are so beautiful,” said Craig. He put his arm around her. Bedroom setting He undressed her. Craig started to undress himself. Sarah helped him to undress. They discussed whether they should use protection. Craig put on a condom. |

La France found that participants predicted that as sexual scripts progressed, the likelihood that Sarah and Craig were going to have sexual intercourse increased. Overall, La France found that the sequence of both verbal and nonverbal sexual behaviors could predict the likelihood that people believed that Sarah and Craig would have sex. For example, in the public setting script, when Sarah says, “No, I came with some friends,” this caused people to think that sex could be off-the-table because the statement indicates that the likelihood of the two leaving alone is lower.36

La France, B. (2010). What verbal and nonverbal communication cues lead to sex? An analysis of the traditional sexual script. Communication Quarterly, 58(3), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2010.503161

Love Styles

An individual’s love style is a persistent attitude about how love is perceived and valued, practiced and experienced, that is usually stable but may change over time.38 For instance, college students may perceive love differently from their parents or guardians because they are in a different stages of life.

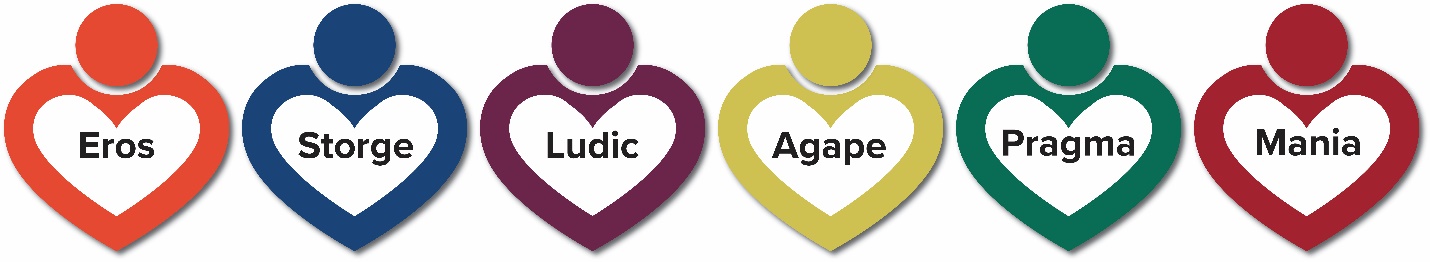

John Lee’s love typology presents six love styles named with Greek and Latin terms for love, that you may identify with more or less so: eros, storge, ludus, agape, pragma, and mania (see Figure 12).39

Eros

Eros is the love style that emphasizes love and romance, physical beauty and attraction, emotional intensity, and strong commitment. Eros love often involves the early initiation of sexual intimacy and lends itself to consecutive monogamous relationships. Tyreek and Alex, who both subscribe to eros, were attracted to each other while participating in different social groups across a loud and sweaty club. They felt immediate sparks when they joined on the dance floor and have had a physically satisfying, though sometimes tumultuous, relationship ever since.

Storge

Storge love resembles, or develops slowly out of, friendship where stability and psychological closeness are valued along with commitment. Passion and intense emotions are not valued as much as they are in the eros love style but the slow burn of storge may lead to a more enduring love. Stanley was a man in his 60s who had never been married but employed Phyllis, who cooked and cleaned for him for over 20 years. Their families were surprised, though pleasantly so, to receive their announcements of marriage.

Ludic

Ludic lovers view love as a game, and play according to their rules in hopes of coming out ahead. The acceptance of multiple partners is likelier within the ludic love style, but so are deception and manipulation. Individuals with this love style have lower tolerance for commitment and strong emotional attachment. Durga likes to have several boyfriends at different stages so that she can avoid being alone when one of them does not work out for her. She tells some of them about this arrangement and hides it from others.

Agape

In contrast, agape love involves altruism, giving, and other-centered love. This love style approaches relationships in a non-demanding style with gentle caring and tolerance for others. Agapic lovers put their partners in front of themselves and often express their feelings through kind actions.

Pragma

Pragma love is practical, logical and rational. In some contemporary cultures and many more of the past, marriages were arranged by families for functional purposes. The first tsar of Russia, Ivan the Terrible, married Anastasia Romanova in 1547 to bring together the Rurikid and Romanov family dynasties and deliver power to him. History shows that their pragmatic love transformed into one of eros, as they wound up entranced by each other. Nonetheless, this pragmatic approach to love, even when arranged, may see romantic partners paired for financial stability, family building, or simple companionship.

Mania

Mania is the love style characterized by dependence, uncertainty, jealousy, and emotional upheaval. This type of lover is generally insecure and needs constant reassurance. Manic lovers may be accused of emotionally suffocating their partners and struggle with the integration-separation dialectic presented earlier in this chapter.

These love styles should not be considered to be mutually independent. An individual may approach love from an erotic stance but find and enjoy love that provides financial stability. You may find that several of the love styles seem to reflect your personality and preferences, as well. As with stage models of relational progress, the love styles are less about being predictive or prescriptive and more about being descriptive of behaviors we can identify from the realm of romance.

- Sequences of communication and behavioral expectations for dating and initiation of sex have been developed.

- The types of love are eros, ludus, mania, storge, pragma, and agape.

- Each love style can be found in all individuals, but some love styles are more prominent for each of us than are others.

Exercises

- Discuss why dating scripts are useful to publish and share. What are some significant aspects of your dating script that seem to be missing from Rose and Frieze’s?

- Determine the love style of each of your parents and grandparents, as well as your own. Describe how your love style developed and whether it was more learned or more an innate characteristic you possess.

Key Terms

active

Strategy of asking around about, or investigating, another person to learn information about them.

agape

The love style that involves altruism, giving, caring, kindness, and other-centered love.

anticipation of future interaction

The belief that we will deal with someone again, thus boosting the need to reduce uncertainty.

attraction

Interest in another person and a desire to get to know them better.

avoidance strategies

Used to evade communication that might threaten a relationship.

avoiding

The fourth stage of Coming Apart when a couple stays away from each other entirely, ceases communication, and considers moving out of the shared residence.

balance strategies

Used to maintain equality in the relationship so that partners do not feel underbenefited or overbenefited.

bonding

The final stage of Coming Together when commitment is increased and announced to wider social networks.

boundary turbulence

Chaotic condition resulting when violations of explicit or implicit privacy rules are broken within a relationship.

circumscribing

The second stage of Coming Apart, when partners strive to limit the number of interactions and amount of communication with each other.

comparison level (CL)

The minimum standard for satisfaction that a relational partner is willing to tolerate.

comparison level of alternatives (CLalt)

The threshold for satisfaction in a relationship determined by available alternative arrangements.

complementary

When people fulfill each other’s needs by featuring differing characteristics.

contact frequency

How often relational partners communicate with each other.

deviance

Behavior that is unexpected or out of place and boosts the need to reduce uncertainty.

differentiating

The first stage of coming apart when parties start to disengage with their identity as a couple in favor of their own.

dialectics

Opposing forces that create everyday experiences of feeling pushed and pulled at the same time.

direct strategies

Used to remind a partner of relationship objectives.

duration

The length in time of a relationship.

eros

The love style that emphasizes love and romance, physical beauty and attraction, emotional intensity, and strong commitment.

experimenting

The second stage of coming together when “small talk” happens and commonalities are discovered.

gender

The behaviors and traits society considers masculine and feminine.

goals

Expectations and hopes for relational functions and outcomes.

incentive value

The belief that knowing someone will benefit us in some way, thus boosting the need to reduce incertainty.

initiating

The first stage of coming together when making contact and signaling interest are the goals.

integrating

The fourth stage of coming together when deeper levels of expectations and commitment, perhaps including exclusivity, are reached.

intensifying

The third stage of coming together when identity as a couple is established and knowledge about partners increases greatly.

interaction variability

The variety of interaction types experienced, and topics covered, with particular relational partners.

interactive

Strategy of participating in interaction with another person to learn information about them.

love style

A persistent attitude about how love is perceived and valued, practiced and experienced, that is usually stable but may change over time.

ludic

The love style that features viewing of love as a game to be played according to rules that include acceptance of multiple partners, deception, and manipulation.

mania

The love style characterized by dependence, uncertainty, jealousy, and obsessive need for affirmation.

passive

Strategy of observing another person to learn information about them.

physical attraction

The degree to which one person finds another person aesthetically pleasing.

pragma

The love style that is practical, logical and rational, resulting sometimes in arranged relationships.

privacy boundaries

Symbolically placed borders between personal private information and details that are shared with others.

relationship

A connection or association between people that is marked by affiliation, attachment, and commitment.

relational dialectics

A “dynamic knot of contradictions in personal relationships; an unceasing interplay between contrary or opposing tendencies”20 such as integration vs. separation, expression vs. privacy, and stability vs. change.

relationship maintenance

Behaviors and strategies that enable stabilization point between relationship initiation and potential relationship destruction.

romantic relationship

A union that features any or all of: affection, caregiving, shared relational identity, and intimacy in the form of emotional, intellectual, physical or sexual closeness.

sex

A person’s biological status as male or female, as determined by chromosomes and secondary sex characteristics.

sharing

The process of revealing and disclosing information about oneself to another.

similarity thesis

The idea that we tend to form relationships with others who are like us due to validation, predictability, and affiliation.

social attraction

The degree to which an individual is seen as entertaining, intriguing, and/or fun to be around.

stagnating

The third stage of Coming Apart when the relationship has stopped improving or growing and emotional inertia blocks hopes for reconciliation.

storge

The love style that resembles, or develops slowly out of, friendship where stability and psychological closeness are valued more than passion.

support

Any message or behavior that conveys caring or comfort to another person so as to improve their condition.

task attraction

The perception that another possesses specific knowledge, skills, and/or contacts that may help with accomplishing specific goals.

terminating

The fifth and final stage of Coming Apart, and tenth overall, when the parties end the relationship, gradually or suddenly, and make arrangements for life after the “break-up.”

uncertainty

An uncomfortable state of not knowing much or enough about something or someone.

Notes

A connection or association between people that is marked by affiliation, attachment, and commitment.

A union that features any or all of: affection, caregiving, shared relational identity, and intimacy in the form of emotional, intellectual, physical or sexual closeness.

The length in time of a relationship.

How often relational partners communicate with each other.

The process of revealing and disclosing information about oneself to another.

Any message or behavior that conveys caring or comfort to another person so as to improve their condition.

The variety of interaction types experienced, and topics covered, with particular relational partners.

Expectations and hopes for relational functions and outcomes.

Interest in another person and a desire to get to know them better.

The degree to which one person finds another person aesthetically pleasing.

The degree to which an individual is seen as entertaining, intriguing, and/or fun to be around.

The perception that another possesses specific knowledge, skills, and/or contacts that may help with accomplishing specific goals.

The idea that we tend to form relationships with others who are like us due to validation, predictability, and affiliation.

When people fulfill each other's needs by featuring differing characteristics.

The first stage of coming together when making contact and signaling interest are the goals.

The second stage of coming together when “small talk” happens and commonalities are discovered.

The third stage of coming together when identity as a couple is established and knowledge about partners increases greatly.

The fourth stage of coming together when deeper levels of expectations and commitment, perhaps including exclusivity, are reached.

The final stage of Coming Together when commitment is increased and announced to wider social networks.

The first stage of coming apart when parties start to disengage with their identity as a couple in favor of their own.

The second stage of Coming Apart, when partners strive to limit the number of interactions and amount of communication with each other.

The third stage of Coming Apart when the relationship has stopped improving or growing and emotional inertia blocks hopes for reconciliation.

The fourth stage of Coming Apart when a couple stays away from each other entirely, ceases communication, and considers moving out of the shared residence.

The fifth and final stage of Coming Apart, and tenth overall, when the parties end the relationship, gradually or suddenly, and make arrangements for life after the "break-up."

An uncomfortable state of not knowing much or enough about something or someone.

The belief that we will deal with someone again, thus boosting the need to reduce uncertainty.

The belief that knowing someone will benefit us in some way, thus boosting the need to reduce incertainty.

Behavior that is unexpected or out of place and boosts the need to reduce uncertainty.

Strategy of observing another person to learn information about them.

Strategy of asking around about, or investigating, another person to learn information about them.

Strategy of participating in interaction with another person to learn information about them.

The behaviors and strategies that enable the stabilization point between relationship initiation and potential relationship destruction.

Used to evade communication that might threaten a relationship.

Used to maintain equality in the relationship so that partners do not feel underbenefited or overbenefited.

Used to remind a partner of relationship objectives.

The minimum standard for satisfaction that a relational partner is willing to tolerate.

The threshold for satisfaction in a relationship determined by available alternative arrangements.

Symbolically placed borders between personal private information and details that are shared with others.

Chaotic condition resulting when violations of explicit or implicit privacy rules are broken within a relationship.

Opposing forces that create everyday experiences of feeling pushed and pulled at the same time.

A “dynamic knot of contradictions in personal relationships; an unceasing interplay between contrary or opposing tendencies”20 such as integration vs. separation, expression vs. privacy, and stability vs. change.

A person's biological status as male or female, as determined by chromosomes and secondary sex characteristics.

The behaviors and traits society considers masculine and feminine.

A persistent attitude about how love is perceived and valued, practiced and experienced, that is usually stable but may change over time.

The love style that emphasizes love and romance, physical beauty and attraction, emotional intensity, and strong commitment.

The love style that resembles, or develops slowly out of, friendship where stability and psychological closeness are valued more than passion.

The love style that features viewing of love as a game to be played according to rules that include acceptance of multiple partners, deception, and manipulation.

The love style that involves altruism, giving, caring, kindness, and other-centered love.

The love style that is practical, logical and rational, resulting sometimes in arranged relationships.

The love style characterized by dependence, uncertainty, jealousy, and obsessive need for affirmation.