Persuasion

Learning Objectives

- Understand what persuasion is as well as how valuable and difficult it is.

- Affect evaluations of worthiness and believabilty by establishing dimensions of credibility.

- Recognize that influence can be achieved through conditioning to create strong associations and by appealing to motivations.

- Discriminate between the qualities and outcomes of central and peripheral route processing of information and decision making.

- Frame a recommended behavior as a solution to a problem.

Fatima can’t decide if she is more annoyed with her best friend, Yara, or with herself. Last spring, Fatima was so excited to get an internship in Chicago with a top-tier marketing firm for the summer. But, Yara convinced her that she was too worn out from a long school year and should spend the summer relaxing with Yara’s family at their seafront property in Long Island’s Hamptons. It was beautiful and there were some good times but Fatima found herself doing all sorts of activities that only really interested Yara, like clamming, tanning, and hunting for both beachy souvenirs and beefy bronzed boys.

Another summer is approaching and Fatima has somehow managed to snag the same internship opportunity in Chicago. Knowing that she was set in her resolve to do it this time, Yara managed to talk Fatima into splitting an apartment in Chicago where, without a doubt, she will spend her time partying and making it difficult for Fatima to stay focused on her work.

Fatima was all ready to blame herself for being such a pushover. Then she remembered that she had recently turned down two boys who were aggressively pursuing her and also shut down several canvassers who tried to get her to sign a petition on campus. Meanwhile, she overheard Yara spend hours on the phone convincing Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion representatives to restore her immaculate credit score even though she had been delinquent paying credit card bills.

It was now clear to Fatima that Yara was some kind of master persuader. What about her, or what she does, or what she says, leads people to do pretty much whatever she wants them to?

Have you ever tried to swap seats with a stranger on an airline? Ever negotiated the price of a car? Ever tried to convince someone to recycle, quit smoking, or let you into their lane in traffic? Has anyone asked you out on a date, sent you an email about a store sale, or tried to get you to vote? If so, you probably agree that persuasion is a common presence in our everyday lives.

The Impact of Persuasion

Charli D’Amelio became popular for her Tik Tok dance videos and proceeded to become the first human to accrue 100 million followers. She has parlayed her influence into sponsored endorsements with the Hollister clothing company, Dunkin Donuts, Pura Vida Charli D’Amelio bracelets, Orosa Beauty nail polish, EOS Cosmetics lip balm, Morphe lip oil and concealer, and along with her sister, the Charli & Dixie Simmons Memory Foam Mattress. D’Amelio was the highest-earning TikTok female personality in 2019 and the highest-earning personality on the app in 2022. Who ever said persuasion doesn’t pay?

Persuasion is the communicative process by which one person influences what another person thinks or believes, feels, or does. It is often the primary goal that someone in an interaction has for their conversational partner. Maybe you want to convince your boss at the movie theatre concession stand not to blame you for the disrepancy between soda sales and cups used. This is critical as you can’t afford to lose this job. However, you don’t want to betray your favorite co-worker, Sal, who has been doling out free sodas to customers he thinks are “hotties.” Preserving your relationship with Sal is your secondary goal (i.e., relational) while escaping the blame is the first order (i.e., persuasive).

To fully understand what we mean by this act of influence known as persuasion, we should recognize some of its most interesting characteristics: prevalence, levels of impact, ethical considerations, and difficulty.

Prevalence

Simply put, persuasion is (almost) everywhere. Advertisers and marketers throw products and services at us with every entertaining media experience on social media platforms and traditional mass media outlets. Teachers try to get you to read textbook chapters like this one. Your sibling wants to borrow your favorite jacket. You need to convince your roommate to get their share of the rent paid on time. Credit card representatives and recycling activists stalk us on campus. Your Mom needs you to call every weekend no matter how busy you are. You’ll just die if you don’t get Megan to take your shift on the Friday of the Post Malone concert that you won tickets for. And on. And on. And on.

Levels of Impact

There are three commonly recognized levels of impact that persuasion may have. The first is the cognitive level, which concerns the things we think or believe. Getting a skeptical fan to accept that the Kansas City Royals’ young pitching staff will make them a Central Division contender this summer is a cognitive level persuasive effort. So is convincing someone that God exists or that they don’t.

The second level of persuasive impact is the affective. The term, affect, is often used in pyschology literatures as a stand-in for emotion. The affective level includes attitudes, opinions, positions. values, etc. Making your cousin, the St. Louis Cardinal fan, like the Royals more is affective level persuasion as is establishing vaping as anl alternative to smoking that is way cooler.

The third level of persuasive impact is the behavioral. Attempting to instill a change in action is the realm of the behavioral level. Bringing me back a Coke when you head off to the vending machine for Cheetos is a simple behavioral persuasion goal. Training your pet ferret to stop eating the curtains counts too, as does persuading your neigbor to stop cranking Broadway show tunes when he gets drunk after midnight. Health communication scholars and safety officials are often interested in accomplishing habitual behavior change like eating reasonably portioned meals or staying out from under your tractor during repairs.

Sometimes we pursue persuasive objectives of different levels of the same time. Political campaigners design yard signs to induce you to be aware of the candidate (i.e., cognitive), like them more (i.e., affective), and actually show up to the polls to vote for them (i.e., behavioral).

Ethical Considerations

It is nearly impossible to overstate the importance of persuasion. Companies’ fortunes, if not their existence, ride on the effectiveness of their marketing and advertising campaigns. Fostering your patient’s adherence to a newly prescribed diet can prevent their pre-diabetic diagnosis from progressing to a possibly deadly condition. Getting your future father-in-law to like and trust you is definitely a real advantage.

Clearly, there are numerous and massive benefits to possessing the powers of persuasion. In fact, it is practically a superpower. And we hope you use it for good as a superhero would. Don’t lie to your targets to get them to agree. Don’t manipulate their emotions unfairly. Don’t leave out information they need to make a fully informed decision.

But do approach them with what we will call “good will” in the next section on credibility. It is okay if you will benefit from a successful persuasive attempt (e.g., meeting your sales quota, keeping your job, lightening your work load) but not if it is at the expense of your persuadee. Ideally, they will benefit as much as, if not more than, you.

If Ricky Roma, from the film Glengarry Glen Ross, wants to sell one more plot of land before the sales contest ends so that he wins a car instead of a set of steak knives, that’s understandable. What is not cool or moral or ethical is that Roma knows his mark, Mr. James Lingk, will meet financial ruin if he agrees to the proposed purchase.

Difficulty

When anything is super valuable, there’s a good chance it’s super hard, too. Persuasion is incredibly difficult to achieve. Think of all the citizens of the United States who have died because they did not wear their seatbelts even though wearing them has one of the highest benefit (e.g., avoiding paralysis or death) to cost (e.g., a two-second arm motion) ratios and our government agencies have spent millions of dollars trying to convince us to buckle up.

Two of the major reasons that persuasion is so hard are that people develop strategies to resist persuasive efforts and that they are not always terribly motivated to be persuaded in the first place.

Ways of Resisting Persuasion

One way to avoid persuasion is to avoid persuasion. Huh? Did you read that right? Yep. If you don’t want to be persuaded, staying away from likely sources of influence is a pretty smart approach. So we don’t listen, watch, or click if we think the speaker, news personality, or Instagram influencer is likely to contradict our current way of thinking or doing.

Persuasion resisters may practice a famous logical fallacy known as “ad hominem.” This is focusing judgment on the provider of a message rather than on the message itself, ” Bobby from Accounting makes a good point, but I don’t like that guy; he smells weird.”

Particularly frustrating for the persuader is when their target agrees only to back off later. You might get the salesman to hang up the phone by agreeing that you need a new garbage disposal. However, when he calls to schedule a home sales visit, you tell him that you have reconsidered.

Finally, there is a commonly used approach to help other people defend themselves against unwanted persuasion. It is usually referred to as “social inoculation.”1 Research has shown that people who are subjected to weak versions of a persuasive message are less vulnerable to stronger versions later on, in much the same way that being exposed to small doses of a virus immunizes you against full-blown attacks. In a classic study by McGuire,1 subjects were asked to state their opinion on an issue. They were then mildly attacked for their position and then given an opportunity to refute the attack. When later confronted by a powerful argument against their initial opinion, these subjects were more resistant than were a control group. In effect, they developed defenses that rendered them immune.

But why is it so important to build up defenses to fight off persuasion? Because people don’t generally like to be persuaded for a variety of reasons.

Reasons For Resisting Persuasion

Many folks don’t want to be persuaded because to acquiese is to incur costs. If you’re convinced to clean the house, there go a few hours. Makeup lady at Dillard’s cosmetics counter influences you to start using a night repair skin serum? 48 bucks! Changing your position on a reproductive rights controversy means you will have to remind yourself of it every time the topic comes up. Being persuaded usually means you have to invest in some way.

Remember that there are different levels of impact that persuasive attempts may pursue. You might only be chasing one of them but the others might be attached. Veronica just wants the kids at her cafeteria table to stop eating meat, at least around her. This is a behavioral imperative. But there may be some cognitive development needed to achieve the behavioral goal. Maybe her classmates’ lack knowledge or awareness (i.e., cognitive) about the levels of suffering animals endure when raised for slaughter. Or perhaps they don’t care about (i.e., affective) animals’ feelings. Or, Veronica’s! So we may need to foster influence on other levels to achieve it on the desired one. That’s more difficult.

Some can’t be “changed” because their experiences just will not square with it. Your Grandpa is really fun and contemporary but he has always found that Wrangler jeans are the only ones that don’t bunch up uncomfortably on him in the seat. No amount of Levi, Gap Factory, Calvin Klein, or Lucky Brand promotions is going to sway him to change his pants!

Ego involvement plays another role in persuasion resistance. In a way, yielding to the belief or attitude or act of another, that contradicts with your own, is an admission of having been wrong. Many fight the perception, held by themselves or others, that they are wrong. Switching up positions also conveys a whiff of inconsistency that most would rather avoid. A politician who has shown the openness and flexibility to allow their mind to be changed on an issue is very likely to be labeled “wishy washy” or “a waffler” by their opposition.

The last item, on this inexhaustive list of reasons that we may not desire to be persuaded, is our inherent doubt of the potential persuader’s credibility. Are they lying? Do they even know what they are talking about? And why is it so important to them that we change our minds or behaviors, anyway? Will it benefit them more than us? We next further explore credibility.

Key Takeaways

- Persuasion is a powerful mode of shaping the world and the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of others.

- Persuasion is difficult to accomplish as its targets have multiple reasons for resisting it and many ways to do so.

- An ethical perspective on altering the positions and practices of others is essential.

Exercises

- Who is the hardest person in your life to persuade of anything? Why do you think that is?

- Who in your life has the easiest time persuading you? Why do you think that is?

- In a group, generate a list of unethical instances of persuasion and discuss what could be done to make them less objectionable.

Source Credibility

If there is one positive association between variables you can expect to hear about when you take a communication studies class, it is that of persuasiveness and credibility. The Greek figure of most historical significance to the field of communication studies, Aristotle, focused much of his attention on how public speakers could be convincing to audiences. He offered three proofs, or standards for evaluating their persuasiveness. Logos is their logic, pathos is their use of emotion, and ethos is their known character, or credibility.

Credibility is a characteristic we assign to each other that determines whether we pay attention to, and believe, each other. Hopefully, you already see how vital the assignment of credibility to a potential persuader is to their success. How can we even inform someone else if they have decided not to listen to us or to pay us no mind? And how can we hope to get someone else to do something that they would not do otherwise, if they have determined that they cannot believe what we tell them?

As critical as the credibility of the source is to their persuasiveness, it is lucky that we have the opportunity to earn it. The following list of eight dimensions of credibility is a virtual road map for assuring a better chance of successfully persuading. For each of these we check off with a target individual or audience, the amount of attention and belief they invest in us increases.

Competence

Perhaps the most weighted indicator of credibility, competence is the characteristic of possessing knowledge about, or experience with, a topic. Your friends turn to Arvid for advice about dining because he is such a foodie and consumes every restaurant review he can. The veteran journalist who has won several regional awards for reporting impresses students in her college course as someone who knows what she is talking about. They cannot help but pay attention when she speaks and believe what she says.

Good Will

When your interaction with someone else is guided by your desire to help them, to leave them better off than you found them, you are displaying good will towards them. Mary Jane, a Nissan showroom salesperson, is often met with resistance to her persuasive pitches because of the deficit in good will associated with her job. The stereotype of car sales personnel is that they will do anything, including stick customers with lemons, to obtain their sales commissions. This is why Mary Jane has a file of happy, satisfied customers to serve as references about her past good will for clients.

Similarity

It may just be human nature, but most people are comfortable hanging out with and trusting others who are like them. When Martina offers style tips to Isabella, the fact that they are of the same age, in the same sorority, and from the same hometown, increases Martina’s credibility.

Idealism

Conversely to the appearance of similarity on this list, idealism is a dimension of credibility, as well. It is the quality of being unlike the targets of persuasion but in ways that they will admire and/or aspire to. Former Major League Baseball players, Kevin Seitzer and Mike Macfarlane, opened the Mac N Seitz training facility in 1996. They rightfully projected that young athletes who dreamed of being professionals like them, would want to receive their instruction.

Charisma

Charisma is almost another way of saying inherent credibility. Some people just seem to be born with enough attractiveness or charm or gravitas that others just pay attention when they are around. Though they could not be more different in how they exhibit it, former presidents Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump all benefit from their larger than life personas, which captivate Americans.

Dynamism

There is something to be said for good old-fashioned enthusiasm. When a colleague wants to be there at work, is smiling and animated, and having a good time, they are exhibiting dynamism. So, we find them more credible than the grouch who reluctantly shows up to put in little effort, and complains nonstop about being there.

Trustworthiness

Others consider us trustworthy when they have faith in us because we are honest, consistent, and reliable. A deficit in trustworthiness will almost certainly trigger a similar shortage in believability. The quickest route to another’s doubt is dishonesty. In fact, when caught in a lie, we are likely to be asked, “how can I trust you again?” A reputation for honesty is difficult to establish and astonishingly easy to shatter.

Consistency is another way that trustworthiness is gauged. If you give everyone the same version of a story or opinion, that is consistency. If you not only “talk the talk,” but “walk the walk,” that is consistency. Hypocrisy is the opposite of consistency. Reliability means that a person is predictable and steady; they can be counted on.

Once you have provided someone else a reason to distrust your honesty, to find you inconsistent, or to be unreliable, you have damaged your credibility with them.

Power

In its simplest form, power is the ability to reward or punish someone. If Jeanine has the ability to make Fredo feel special, to withhold affection that he desires, to help him plan a dream vacation, to screw up his marriage, or to make others think more or less of him, then Jeanine has power over Freddy. When we find others powerful, we also find them to be more credible. Anyone who can guide your fate towards more or less favorable directions is at least worth paying attention to!

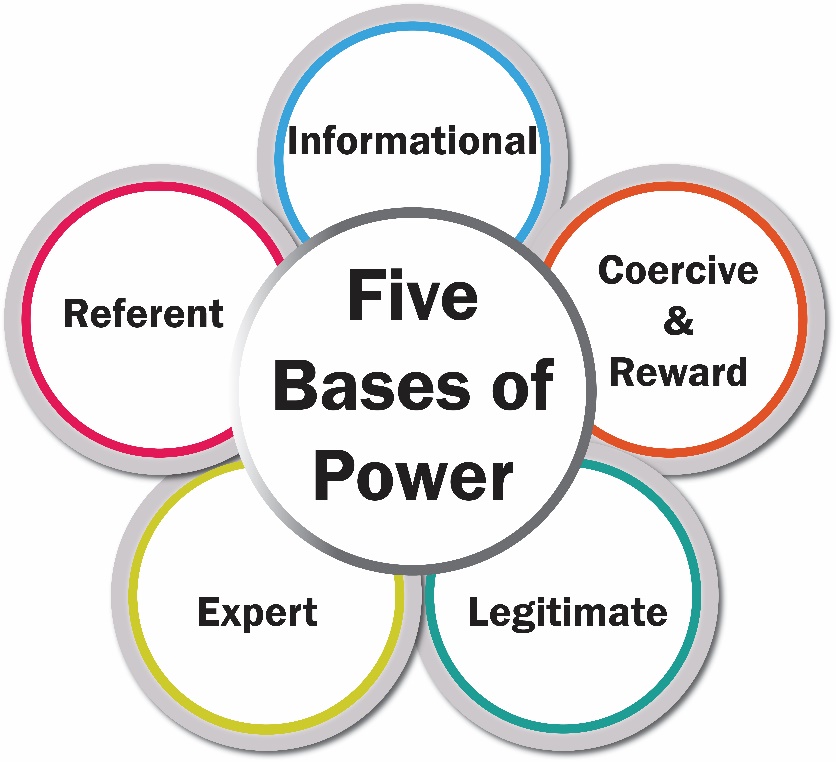

French and Raven’s Five Bases of Power

In 1959, John French and Bertram Raven identified five unique bases of power (i.e., informational, coercive and reward, legitimate, expert, referent) that people can use to enhance their own credibility and thus, better influence others.2

Informational

The first basis of power is the last one originally proposed by Raven.3 Informational power refers to the ability to bring about a change in thought, feeling, and/or behavior through the provision of information. For example, since you initially started school, teachers have had informational power over you. They have provided you with a range of information on history, science, grammar, art, etc. that shape how you think (e.g., what constitutes history?), feel (e.g., what does it mean to be aesthetically pleasing?), and behave (e.g., how do you properly mix chemicals in a lab?). In some ways, informational power is very strong, because it’s often the first form of power with which we come into contact.

Coercive and Reward

The second base of power is part coercive power, which is the ability to punish an individual who does not comply with one’s influencing attempts, and part reward power (i.e., the third base of power), which is the ability to offer an individual rewards for complying with one’s influencing attempts. These are two sides of the same coin. Your parent or guardian who could take away your Nintendo Switch if you neglected your chores or finally get you that puppy if you got good grades, held coercive and reward power over you. This base is closest to the elemental definition of power provided above.

Legitimate

The fourth base of power is legitimate power, or the valid right to influence another person. French and Raven argued that there were two common forms of legitimate power: cultural and structural. Cultural legitimate power occurs when a change agent is viewed as having the right to influence others because of their role in the culture. For example, in some cultures, the elderly may have a stronger right to influence than younger members of that culture. Structural legitimate power, on the other hand, occurs because someone fulfills a specific position within the social hierarchy. For example, your boss may have the legitimate right to influence your thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors in the workplace because they are above you in the organizational hierarchy.2

Expert

The fifth base of power is expert power, which is the ability to influence others because of one’s knowledge. For example, we often give our physicians the ability to influence our behavior (e.g., eat right, exercise, take medication, etc.) because we view these individuals as having specialized knowledge. Expert power is a close cousin to the original quality of credibility noted earlier, competence.

A contributing factor to the recent political climate of division in the United States is the Dunning–Kruger effect, or the tendency of some people to inflate their expertise when they really have nothing to back up that perception.39 When people believe they can be counted as experts and that their intution is just as valuable as valid science and research, any expert power they accrue can become highly problematic within a democratic society such as ours.

Referent

The final base of power discussed by French and Raven is referent power, or the ability to influence another person based on their desire to be associated with the persuader. Referent power often emerges as the person desiring the association adopts similar characteristics to the person they admire. This is a decent approximation of the separate dimension of credibility known as idealism. If a tween girl begins wearing Pura Vida Charli D’Amelio bracelets so as to enhance her association with the Tik Tok influencer, she is under D’Amelio’s referent power.

Key Takeaways

- Credibility, the perception that a message source is worthy of being heard and believable, is a large factor in persuasive success.

- There are at least eight dimensions, including knowledge/experience, similarity, and good will, that can be displayed to earn credibility from others.

- Five bases of power serve to enhance both credibility and persuasiveness.

Exercises

- Why is it that similarity and idealism can be simultaneously effective for establishing credibility while being such opposites of each other?

- Have a partner generate a persuasive task for you to consider accomplishing with a particular target. Describe the credibility dimensions you posess that would be most helpful in that scenario. Reverse roles. Continue as long as it is fun and/or informative!

Persuasive Approaches

Besides wielding impressive amounts of indicators of credibility (i.e., competence, good will, similarity, idealism, charisma, dynamism, trustworthiness, power) to garner the attention and belief of others, there are an untold number of approaches to understanding how people make their decisions so as to more effectively influence them. Persuasion is so valuable and so difficult that practitioners and scholars from the fields of communication, psychology, marketing, consumer behavior, political campaigning, health advocacy and more, have been hard at work developing theories, models, techniques, strategies and tactics to inform the messages persuaders use to accomplish their goals.

This book, or really any book, is incapable of containing all of these approaches to persuasion but we can provide a good sample of them. Our philosophical metaphor here is a contractor’s toolbelt. A person who makes their living constructing and fixing things is likely to value having a toolbelt that will contain an implement for any task they might encounter. We hope to provide you with some persuasive tools in the form of well-supported concepts and theories and trust that you will develop the skills of using them and also choosing the right one for the job at hand (i.e., persuading a particular person of a particular thing)!

We will group different approaches to enhancing our persuasive sophistication under the headings of Conditioning Approaches, Motivational Approaches, and Information Processing and Elaboration.

Conditioning Approaches

A couple of very old, but still relevant, ways of understanding why people (or even animals!) do what they do can inform our attempts to persuade them. They both hinge on conditioning, or the act of repeatedly and consistently associating things in perception to create particular desired outcomes.

Classical Conditioning

In 1897, more than 125 years ago, Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov first promoted his famous studies that live on today under the rememberance of “Pavlov’s dogs.” Pavlov was interested in the idea of getting the same reactions to different things. He decided to associate an original stimulus with a new one repetitively and consistently until the new one elicited the same response as the original had.4 Dr. Pavlov noted that dogs salivate when you feed them. He began ringing a bell every time he fed them, and naturally, each time they still salivated.

Then one day, after consistently and repeatedly presenting the food (i.e., original stimulus) and the bell (i.e., new stimulus) together, he only rang the bell. And the dogs would salivate anyway. They had been conditioned to associate the stimuli so well that, at least in terms of their responses, the two stimuli were one and the same.

This process of classical conditioning is applied to humans when advertisements tightly and repetitively associate beer and fun or boring cars with attractive young models and when campaigns label an opposing candidate with the same demeaning nickname everytime they’re referenced.

Operant Conditioning

In the 1930s, building on the research of cat-studying behaviorist Edward Thorndike, Harvard University psychologist B.F. Skinner investigated birds and rodents to complete his understanding of operant conditioning.

When animals performed particular tasks, they were rewarded for it with incentives like food or punished for it as with bright lights and loud noises. Critically, they received the reward or punishment each and every time they commited the act. In the case of rewarding behavior, this positive reinforcement conditioned more of the behavior. In the case of punishing behavior, negative reinforcement conditioned less of the behavior.

What Skinner demonstrated was that operant conditioning could effectively associate behaviors with consequences and influence behavior with encouragement or discouragement of it in the future.5

Humans can be persuaded to quit smoking with consistent electric shocks, to stay out of the street when playing with consistent punishment, or to clean up their room for consistent extra time getting to play Minecraft and Roblox.

Motivational Approaches

Decision making may sometimes be driven by needs or motivations. The Introduction to Communication chapter includes discussion of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs which helps to explain how we may persuade someone to join the Army by highligting their Self-Actualization needs or to join a campus organization if motivated by a need for belonging to social groups. When we understand ways that persuasive targets may be motivated to minimize discrepancies about themselves or to act in accordance with friends and family, we can apply that knowledge in efforts to influence them.

Cognitive Dissonance

Leon Festinger was a social psychologist who made many theoretical contributions to our understanding of human cognition. Among them was a concept he called cognitive dissonance, which is an unpleasant sensation of experiencing regretted or inconsistent beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors. He studied survivors of natural disasters who were especially welcoming of dire news only because it confirmed the fear that they were feeling. In fact, his body of observations and experiments revealed many surprising findings (e.g., subjects enjoying a gross task like eating insects more if forced to by a less likeable researcher) about how individuals deal with dissonance.

His most famous work was a collaborative book, When Prophecy Fails, detailing how the members of a 1950s doomsday cult, who believed life on Earth would soon be dominated or terminated by space aliens, doubled down on their devotion to it even with the exposure of its leader as a charlatan, or fake. It was psychologically easier for the cult members to continue their investment in the failed cause than to admit that their prior efforts had been pointless.6

And therein lies the potential persuasive power of cognitive dissonance. We are very motivated to not experience the awful feeling that we have hurt ourselves with our decisions or are acting in ways that are inconsistent with our values.

Union representatives may increase membership among Amazon workers by proving to them that not unionizing will lead directly to their own worse working conditions and lower pay. A financial adviser may successfully inspire a client to spend less and save more by having them visualize how awful it will be to have to move out of their home in retirement if they don’t invest more in the company pension plan now.

Theory of Reasoned Action

In the late 1960s through the mid-1970s, Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen introduced their Theory of Reasoned Action to explain how individuals decide whether they are inclined to do something, like buy a particular kind of car or adopt a certain (un)healthy behavior. The researchers actually developed an algebraic equation, and quantified participants’ responses about attitudes and desires, all in order to predict how likely they were to adopt specific behaviors.

What it boils down to is that a major factor in whether we intend to do something is how we feel about it. If you think getting plastered drunk every weekend night is cool, you are a lot more likely to do it than if you think it’s irresponsible, or even disgusting, behavior.

The Theory of Reasoned Action also recognizes the beliefs or attitudes about the examined behavior of an individual’s reference group(s), the people who surround them socially, like friends or family. Critically, the person’s motivation to comply with the reference group, to fit in with those they are around the most, determines how their intentions are shaped. This becomes most interesting when one’s feelings are different from one’s peers and may begin to move in the direction of the reference group’s values.7

The Theory of Reasoned Action can serve not just to help predict a person’s intentions based on their feelings about a behavior, and those of their peers, but also to inform efforts to persuade them.

Benson and Tanner are heavily recruiting an impressive new student named Zach, to join their chapter of the Sigma Chi fraternity. If guided by the Theory of Reasoned Action, they would first try to address Zach’s skepticism about Greek life and Sigma Chi. The more he likes it, the more likely he will be to join. When it becomes clear that he likes apartment living more than the fraternity house atmosphere, Benson and Tanner start trying to convince Zach’s friends of the benefits of Greek life. Once this is successful, they need to somehow increase Zach’s motivation to conform to his peers’ attitudes.

Information Processing and Elaboration

Richard Petty and John Cacioppo devote the first chapters of their incredible 1996 book about persuasion to reviewing theories that adopt the conditioning or motivational approaches, as well as judgmental and attributional ones, In the book’s epilog, they deliver the Elaboration Likelihood Model, perhaps the approach to persuasion applied by more professionals and practitioners than any other.8

The Elaboration Likelihood Model focuses on the extent to which we apply effort in making our decisions. Petty and Cacioppo feel that we make a good share of our decisions with little to no elaboration, the effortful and careful processing of information, alternatives, and possible outcomes. These represent what the researchers call the peripheral route to decision making. The peripheral route to persuasion is one in which influencers look to induce these fast, simple decisions. Most of our other decisions do contain a significant amount of elaboration and represent the central route to decision making and persuasion.8

Have you ever been checking out your purchases at a grocery store and you reach out and add a pack of gum? Or done something at work in a particular way because that’s how everyone else seems to do it? Or voted for someone you don’t know to represent you in student government just because they have the same major as you? If so for any of these examples, you have engaged in peripheral route decision making. Marketers who arrange to have the gum right in your sightlines and candidates who make sure their major is on the fliers they put up in your building are engaging in peripheral route persuasion.

In the 1980s, before CDs and DVDs and Blu-rays and digital streaming networks, consumers in the United States were puzzled about whether to adopt or abandon each of the VHS and Betamax tape recording and LaserDisc formats for home viewing of content like movies and TV shows. Each of these was costly and had a variety of advantages and disadvantages. Family decision makers had to consider price, quality of picture, functionality of controls, title availability, ability to record, and other factors as well. Clearly, this was a decision that required efforts such as researching features, buying technology magazines, reading reviews, talking to friends, visiting retailers, considering budgets, etc. It is a stellar example of central route decision making and if they were smart, central route persuasion by the marketers of the JVC, Sony, and Music Corporation of America. The VHS format won the battle for American hearts and minds, as many televisions could not deliver the audio and video benefits of Betamax, which also had lesser recording time capabilities. LaserDisc was available for only an extremely small number of movies and could not record at all so it never really had a chance to prevail in these carefully considered, elaborated entertainment choices.

Implications and Factors of Central and Peripheral Routes

A really fascinating yet intuitive implication of the Elaboration Likelihood Model is that decisions reached by the peripheral route are short term and result in little to no commitment. You might easily reach out and snag a different pack of gum if it happens to be available next time. Central route decisions tend to be lasting and may result in commitment and investment in outcomes. Some American families (okay, maybe just a handful of them) still swear by their old VHS recorders today.

You may have figured out by now that persuaders who subscribe to the Elaboration Likelihood Model would do well to predict whether their targets are more likely to engage in central route (i.e., much elaboration) or peripheral route (i.e., little elaboration) processing and adjust their strategies and messages accordingly. Petty and Cacioppo predict that we will engage in central route processing and decision making when we are BOTH willing AND able to do so.

Willingness is determined by our involvement in the issue at hand, how important it is to us, and whether we are making a big investment of time, money, reputation or other resources into the outcome of our decisions. Ability is determined by whether we have the intelligence, skill to learn about, processing tools and freedom from distraction or time constraints. Your position on the new tips and taxes legislation might be arrived at in an offhand manner if you don’t work in the dining sector. But you may put a ton of work into determining whether to install a gas or electric range in your own kitchen renovation.

Persuaders who desire long-term, commitment-inducing decisions in their favor, and who also address targets that are both willing and able to elaborate, should present detailed, fact-filled, serious information about their products, services, or candidates, thus promoting central route decisions. Persuaders who just need a one-time decision or purchase or who address targets that are either unwilling or unable to elaborate, may as well just employ any of the tactics or strategies described in the next section.

Peripheral Route Processing and Persuasion

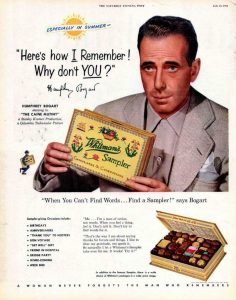

Peripheral route persuaders are likely to employ very simple, fast and easy messages or associations. They may hire a celebrity endorser, rely on a simple slogan, place products where they are readily available, or jazz up product packaging.

Peripheral route persuaders also may attempt to inspire the use of heuristics, which are mental shortcuts for making decisions quickly and easily.

Heuristics

Reciprocity

“There is no duty more indispensable than that of returning a kindness,” wrote Cicero. Humans are motivated by a sense of equity and fairness. When someone does something for us or gives us something, we feel obligated to return the favor in kind. If a colleague helps you when you’re busy with a project, you might feel obliged to support her ideas for improving team processes.

Reciprocity is sometimes referred to as “quid pro quo” arrangements where a favor is met with a favor, or “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” The 45th President of the United States was impeached for, but not convicted of, soliciting a quid pro quo deal with another nation’s president so that his desired legal investigations would earn previously promised foreign military resources.

Social Proof

The social proof heuristic equates with the logic of “everyone else does it and if everyone is doing it, it must be right.” People are more likely to work late if others on their team are doing the same, to put a tip in a jar that already contains money, or eat in a restaurant that is busy (see Figure 9). In a way, the laugh tracks on situation comedies are social proof that allow, and instruct, us to laugh along, too.

Liking

We know that celebrities are rarely experts about products they represent, and that they are being paid to say what they’re saying, so why do their endorsements sell so many products? Ultimately, it is because we like them.

The mix of qualities that make a person likable are complex and often do not generalize from one situation to another. One clear finding, however, is that physically attractive people tend to be liked more. In fact, we prefer them to a disturbing extent; various studies have shown we perceive attractive people as smarter, kinder, stronger, more successful, more socially skilled, better poised, better adjusted, more exciting, more nurturing, and, most important, of higher moral character. All of this is based on no other information than their physical appearance.9

Authority

From earliest childhood, we learn to rely on authority figures for sound decision making because their authority signifies status and power, as well as expertise. We are taught to believe that respect for authority is a moral virtue. We assume that parents, teachers, police, judges, doctors, bosses, and religious leaders possess special access to information and power. So, when they tell us what to eat, who to hang out with, even whether to dance (e.g., the Reverend Shaw Moore and his wife, Vi, in the film, Footloose), we often comply.

Perhaps the most famous study ever conducted in social psychology, the Milgram Experiment, demonstrated that two-thirds of a sample of psychologically normal men were willing to administer potentially lethal shocks to a stranger for being wrong just because an apparent authority in a laboratory coat ordered them to do so.10

Uncritical trust in authority can be problematic for several reasons. First, even if the source of the message is a legitimate, well-intentioned authority, they may not always be correct. Second, when respect for authority becomes mindless, expertise in one domain may be confused with expertise in general. To assume there is credibility when a successful actor promotes a cold remedy, or when a psychology professor offers his views about politics, can spell disaster. Third, the authority may not be legitimate. It is not difficult to fake a college degree or professional credential or to buy an official-looking badge or uniform.

Scarcity

People tend to perceive things as more attractive when their availability is limited. In a classic study, Jack Brehm and Marcia Weinraub placed 2-year-old boys in a room with a pair of equally attractive toys. One of the toys was placed next to a plexiglass wall; the other was set behind the plexiglass. For some boys, the wall was 1 foot high, which allowed the boys to easily reach over and touch the distant toy. Given this easy access, they showed no particular preference for one toy or the other. For other boys, however, the wall was a formidable 2 feet high, which required them to walk around the barrier to touch the toy. When confronted with this wall of inaccessibility, the boys headed directly for the forbidden fruit, touching it three times as quickly as the accessible toy.

Even adults are appealed to easily by the “get it while you still can” heuristic of scarcity. Why in the heck else would eBay make sure that I know how many other people have just viewed the 2021 Upper Deck Skybox Metal Universe Jambalaya Wayne Gretzky hockey card selling at $1800, which is one of only 20 to have ever been produced?

Compliance Gaining Strategies

There are a variety of persuasive tactics and strategies that can easily and quickly be adapted into messages seeking peripheral decisions. A popular anecdote in communication scholar circles is that researchers Gerald Marwell and David Schmitt sat down one night in a restaurant and scrawled out their original sixteen compliance gaining strategies on a napkin. In their 1967 landmark study, they offered these as an initial foray into investigating the types and effects of simple little persuasion and favor-gaining tactics that could easily be designed into messages.11 Many studies have examined the effectiveness of each of the strategies in a variety of contexts (e.g., simple favors, health behavior changes), expanded the original list, and even refuted the whole notion of asking research participants to forecast their reactions to them.

Some of the original strategies were reward (i.e., benefit the target in return for complying; “I’ll pay you back double for a loaner today”), liking (i.e., buttering up the target with flattery before a request; “Have you been working out? I want to have you look at something…”), aversive stimulation (i.e., ceasing punishment only when the target complies; “you’ll keep sleeping on that couch until you apologize”), moral appeal, (e.g., “You have to do it, it’s the right thing”), and negative esteem of others (e.g., “You don’t want your friends to see you in that!”).

Other strategies have been defined such as guilt, direct request, and threat. All kinds of findings have emerged across the compliance gaining strategies when certain strategies have worked best at gaining compliance of certain people in certain situations.

Some have shown that the presence or absence of other variables or conditions increase the odds of successful persuasion for almost any kind of strategy or message employed. One series of studies found that appeals for healthy behavior are enhanced when the compliance seeker and their target share high amounts of intimacy, especially intellectual and emotional closeness.12, 13

Time-Honored Sales Techniques

Potential buyers have been converted into customers by salespeople using very simple foot-in-the-door and door-in-the-face techniques since the heyday of the travelling vacuum cleaner and knife salesmen of the 1950s and 60s.

Foot-in-the-Door

Westerners have a desire to feel and be perceived as consistent. Once they have made an initial commitment, it is more likely that they will agree to subsequent ones especially if the first resulted from a difficult-to-refuse small request. The persuader follows with progressively larger requests to reach what was always the goal from the beginning.

The process is known as getting a foot in the door because salesman were literally trained to at least obtain some interaction with the homeowner by wedging the front of their shoe into the door to prevent it from closing.

Alain is hoping his boss at Helix Consulting, Mr. Hodges, will allow him to work from home full-time just as he did during the pandemic of the early 2020s. He knows that Hodges has a problem with employees not being around and accountable. So, Alain asks permission to spend more time in the home office of one of their major clients and receives it. Soon after, he asks to do so with more cients and next, to meet with them at other locations, hoping all the time to ease his way back into an all Zooming situation.

Door-in-the-Face

Some techniques bring a paradoxical approach to the escalation sequence of foot-in-the-door by pushing a request to or beyond its acceptable limit and then backing off. In the door-in-the-face, sometimes called the reject-then-compromise, sequence, the persuader begins with a large request they expect will be rejected. They want the door to be slammed in their face. Looking forlorn, they now follow this with a smaller request, which, unknown to the customer, was their target all along.

In one study, researchers posing as representatives of the fictitious “California Mutual Insurance Co.,” asked university students walking on campus if they’d be willing to fill out a survey about safety in the home or dorm. The survey, students were told, would take about 15 minutes. Not surprisingly, most of the students declined—only one out of four complied with the request. In another condition, however, the researchers door-in-the-faced them by beginning with a much larger request. “The survey takes about two hours,” students were told. Then, after the subject declined to participate, the experimenters retreated to the target request: “. . . look, one part of the survey is particularly important and is fairly short. It will take only 15 minutes to administer.” Almost twice as many then complied.14

Central Route Processing and Persuasion

There is no shortage of approaches to persuasion that recognize more complex, effortful processing of information and decision making than is evident when peripheral route, short cut, heuristic choices are made. In the health psychology and communication literatures alone there are the Stages of Change Model, Protection Motivation Theory, Extended Parallel Process Model, Problematic Integration Theory, and many others.

This chapter concludes with inspection of one very famous and well-respected representation of the perceptions and thoughts sought by persuaders in efforts to help others, who find themselves in states of involvement and willingness to elaborate, act in ways that are healthiest for them.

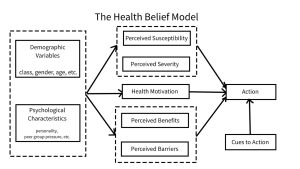

Health Belief Model

In the 1950s, a team of social psychologists and health promotion researchers led by Irwin Rosenstock was struggling to understand why people infrequently took the appropriate steps or recommended precautions to improve or protect their health.

There are so many behaviors that increase (e.g., smoking, drinking, poor diets) or decrease (e.g., exercise, hydration, dental hygiene) health risks and it is difficult to inspire people to do what they should, and to not do what they shouldn’t. Moreover, actual patients, given treatment advice by their health care providers so seldom carry them out fully. At home physical therapy, instructions to finish the entire bottle of medication, or to make dietary changes, are ignored to an alarming degree.

So, Rosenstock began promoting the Health Belief Model that he gets credit for today.15 The Health Belief Model uses a problem/solution or threat/coping sequence to motivate individuals to do what is recommended. Instead of merely providing an instruction to perform a behavior, proponents of the Health Belief Model provide a series of perceptions that frame the recommended behavior as a solution to some problem the target individual faces.

There are five main components to the original Health Belief Model: cues to action, perceived severity (of a problem or health threat), perceived susceptibility (to a problem or health threat), perceived barriers (to performing the recommended behavior), and perceived benefits (to performing the recommended behavior).

The first three elements are related to the threat or problem and motivating the desire to take action to prevent or minimize it. Cues to action are any inputs that get the target person to consider the health threat such as news stories, consultation with a physician, a coworker’s diagnosis, etc. Perceived severity is the degree to which a problem or threat is believed by the target to be serious and bad. Perceived susceptibility is the extent to which the target feels the problem or threat is happening, or could happen, to them. Critically, both the severity and susceptibility perceptions must be extreme enough to promote motivation to do something about the threat/problem. If it is believed that the threat is not suffciently scary and undesirable or that it is very unlikely to occur, the persuasive effort will almost certainly fail.

The last two components have to do with the solution/coping mechanism which should be the behavior that is being recommended. Perceived barriers are anything the target feels will make the recommended behavior difficult or less likely to be performed. Perceived benefits are anything the target feels will make the recommended behavior easier or more likely to be performed. Critically, the benefits must be seen to outweigh the barriers to promote the recommended behavior’s performance.

The four perceptions of the problem/threat (i.e., severity and susceptibility) and the solution/coping (i.e., benefits and barriers) may already exist or may have to be provided with messaging.

For example, Ryan has been noticing that he is a bit heavier than he would like to be and his energy is lagging. He sees a story on a newscast about the increased prevalence of diabetes in people his age (cue to action). His general care provider, Dr. Dawkins, diagnoses Ryan as pre-diabetic. The doctor believes diabetes (threat/problem) could be an outcome for Ryan and wants to get him on a regular exercise program.

Using the Health Belief Model appropriately, Dr. Dawkins shares with Ryan that he is likelier than not (i.e., susceptibility) to become diabetic and that as a disease that can cause circulation problems, eyesight complications, and kidney damage (i.e., severity), he should be motivated to take action. The prescribed treatment is exercise and the two of them discuss what would be entailed. They honestly note that exercise is not great fun for most, takes time out of each day, and may even cost money for a gym membership and workout clothes (i.e. barriers). However, the benefits include helping to prevent the more serious diagnosis, losing weight, building strength and endurance, mood improvement, and social opportunities.

Motivated by thorough consideration of the serious threat that he is truly facing and by the offsetting of barriers by more and larger benefits, Ryan is persuaded to make plans to integrate exercise into his daily lifestyle.

The premises of the Health Belief Model are also applied to dilemmas in other areas of modern life besides health-related issues. For instance, a tax preparation firm might convince potential clients to hire them by framing their services as an affordable solution to the terrible and likely threat of an audit by the Internal Revenue Service.

Key Takeaways

- Conditioning approaches may persuade by creating strong associations between stimuli or between behavior and consequences.

- Motivational approaches may hinge on targets’ needs to reduce dissonance or comply with their peers’ values.

- Central and peripheral routes to decision making and persuasion differ on how much elaboration, or mental effort, targets and their persuaders apply to information provision and consideration.

- The Health Belief Model represents framing a recommended behavior as a feasible solution to a likely and serious threat or problem.

Research Spotlight

There may be a middle ground between the central and peripheral routes of the Elaboration Likelihood Model. A series of experimental investigations shows that processing of complex information may be manipulated by the heuristic of one single instruction.

University of Kansas Communication Studies lecturer and researcher Michael Dennis, with his advisor at Purdue University, Austin Babrow, wondered whether considered decisions about health issues are more influenced by quantitative/statistical information or qualitative/narrative information. The researchers reasoned that the best way to test whether numbers or stories are more persuasive was to give participants contradictory information in the two formats and see which one played a larger role in their reasoning.

Participants were asked to make a prediction about how likely it was that a student they were to read about was sick with either mononucleosis or conjunctivitis (pink eye). Participants were given a description of the multiple symptoms the student was experiencing but were also given a low number as the percentage of students on campus who had the disease. So a high prediction of likelihood the student was sick would indicate that the narrative story was weighed more heavily; a low prediction would indicate the statistic was used more in the processing of information.

Neither qualitative nor quantitative evidence generally or significantly weighed more in participants’ predictions.

However, Dennis and Babrow found that they could shape participants’ judgments by assigning them either a “paradigmatic” or a “narrative” orientation. Participants who were simply instructed to think like a “scientist” and make judgments like “a scientist analyzing data” employed the numeric information more in their predictions. Others instructed to ““call on your general knowledge, sensitivity and empathy” implemented the narrative symptom descriptions more in theirs. Thus, a complex decision task requiring elaboration about contradicting evidence types was affected by a simple heuristic suggestion!

Dennis, M. R., & Babrow, A. S. (2005). Effects of narrative and paradigmatic judgmental orientations on the use of qualitative and quantitative evidence in health-related inference. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 33(4), 328-347.

Key Terms

ad hominem

A logical fallacy of focusing judgment on the provider of a message rather than on the message itself.

affective

The level of persuasive impact consisting of feelings, attitudes, opinions, positions, and values.

behavioral

The level of persuasive impact consisting of actions and habits.

central route

From the Elaboration Likelihood Model, decision making or persuasion that relies on at least a fair amount of elaboration.

charisma

An indicator of credibility, it is enough attractiveness or charm or gravitas to make others pay attention.

classical conditioning

The process by which a new stimulus is so repetitively and consistently associated with an original stimulus that it elicits the same responses as the original.

coercive power

The base of power that is an ability to punish an individual who does not comply with one’s influencing attempts.

cognitive

The level of persuasive impact consisting of thoughts and beliefs.

cognitive dissonance

An unpleasant sensation of experiencing regretted or inconsistent beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors.

competence

An indicator of credibility, it is the characteristic of possessing knowledge about, or experience with, a topic.

conditioning

The act of associating things in perception to create particular desired outcomes.

credibility

A characteristic we assign to each other that determines whether we pay attention to, and believe, each other.

cues to action

Inputs like media or friends that create awareness or concern about a potential threat, in the Health Belief Model.

dynamism

An indicator of credibility, it is a large measure of enthusiasm and animation.

Dunning-Kruger effect

The tendency of some people to inflate their expertise when they really have nothing to support that perception.

elaboration

The effortful and careful processing of information, alternatives, and possible outcomes, to make a decision.

expert power

The base of power that is the ability to influence others because of one’s knowledge.

good will

An indicator of credibility, it is a desire to help another person, to leave them better off than you found them.

heuristics

Mental shortcuts for making decisions quickly and easily.

idealism

An indicator of credibility, it is the quality of being unlike the targets of persuasion but in ways that they will admire and/or aspire to.

informational power

The base of power that is an ability to bring about a change in thought, feeling, and/or behavior through the provision of information.

legitimate power

The base of power that is the valid right to influence another person based on cultural or structural roles.

operant conditioning

The process by which a behavior is so repetitively and consistently associated with a positive or a negative consequence that its continued performance is encouraged or discouraged effectively.

perceived barriers

Anything a persuasive target feels will make the recommended behavior difficult or less likely to be performed, in the Health Belief Model.

perceived benefits

Anything the persuasive target feels will make the recommended behavior easier or more likely to be performed, in the Health Belief Model.

perceived susceptibility

The degree to which a a target of persuasion believes they are vulnerable to a problem or threat, in the Health Belief Model.

perceived severity

The degree to which a problem or threat is believed by a target of persuasion to be serious and bad, in the Health Belief Model.

peripheral route

From the Elaboration Likelihood Model, decision making or persuasion that relies on very little elaboration.

persuasion

The communicative process by which one person influences what another person thinks or believes, feels, or does.

power

An indicator of credibility, it is the ability to reward or punish someone.

referent power

The base of power that is an ability to influence another person based on their desire to be associated with the persuader.

reward power

The base of power that is an ability to offer an individual rewards for complying with one’s influencing attempts.

similarity

An indicator of credibility, it is the sharing of qualities so as to be like another person.

trustworthiness

An indicator of credibility, it is the quality of others having faith in a person who is honest, consistent, and reliable.

Notes

Attribution

The communicative process by which one person influences what another person thinks or believes, feels, or does.

The level of persuasive impact consisting of thoughts and beliefs.

The level of persuasive impact consisting of feelings, attitudes, opinions, positions, and values.

The level of persuasive impact consisting of actions and habits.

A logical fallacy of focusing judgment on the provider of a message rather than on the message itself.

A characteristic we assign to each other that determines whether we pay attention to, and believe, each other.

An indicator of credibility, it is the characteristic of possessing knowledge about, or experience with, a topic.

An indicator of credibility, it is a desire to help another person, to leave them better off than you found them.

An indicator of credibility or romantic potential, it is the sharing of qualities so as to be like another person.

An indicator of credibility, it is the quality of being unlike the targets of persuasion but in ways that they will admire and/or aspire to.

An indicator of credibility, it is enough attractiveness or charm or gravitas to make others pay attention.

An indicator of credibility, it is a large measure of enthusiasm and animation.

An indicator of credibility, it is the quality of others having faith in a person who is honest, consistent, and reliable.

An indicator of credibility, it is the ability to reward or punish someone.

The base of power that is an ability to bring about a change in thought, feeling, and/or behavior through the provision of information.

The base of power that is an ability to punish an individual who does not comply with one’s influencing attempts.

The base of power that is an ability to offer an individual rewards for complying with one’s influencing attempts.

The base of power that is the valid right to influence another person based on cultural or structural roles.

The base of power that is the ability to influence others because of one's knowledge.

The tendency of some people to inflate their expertise when they really have nothing to support that perception.

The base of power that is an ability to influence another person based on their desire to be associated with the persuader.

The act of associating things in perception to create particular desired outcomes.

The process by which a new stimulus is so repetitively and consistently associated with an original stimulus that it elicits the same responses as the original.

The process by which a behavior is so repetitively and consistently associated with a positive or a negative consequence that its continued performance is encouraged or discouraged effectively.

An unpleasant sensation of experiencing regretted or inconsistent beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors.

The effortful and careful processing of information, alternatives, and possible outcomes, to make a decision.

From the Elaboration Likelihood Model, decision making or persuasion that relies on very little elaboration.

From the Elaboration Likelihood Model, decision making or persuasion that relies on at least a fair amount of elaboration.

Mental shortcuts for making decisions quickly and easily.

Inputs like media or friends that create awareness or concern about a potential threat, in the Health Belief Model.

The degree to which a problem or threat is believed by a target of persuasion to be serious and bad, in the Health Belief Model.

The degree to which a a target of persuasion believes they are vulnerable to a problem or threat, in the Health Belief Model.

Anything a persuasive target feels will make the recommended behavior difficult or less likely to be performed, in the Health Belief Model.

Anything the persuasive target feels will make the recommended behavior easier or more likely to be performed, in the Health Belief Model.