Nonverbal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Understand the importance of nonverbal communication in all forms of interaction.

- Recognize the functions of nonverbal communication.

- Provide examples of the channels of nonverbal communication.

Nonverbal communication is defined as communication that is produced by some means other than words such as eye contact, body language, or vocal cues.1 Nonverbal cues are the “show” to verbal communication’s “tell.”

Most people think of communication as the use of the spoken word but that can be supplemented or replaced by what is visually or aurally observed about us. When a classmate asks for a lift back to the dorm, you could augment your “Sure, I can take you,” with a smile and a nod thus affirming your positivity towards the request. If you responded with the same exact words but accompanied them with a sigh and an eye roll, an entirely different impression will be made.

We bet there have been times in your life where an email or text message has been taken the wrong way by its receiver. Maybe you were trying to be playful with your words but the other person found it to be insulting. These sorts of unfortunate outcomes are sometimes the result of a lack of, or deficit in, nonverbal information. If the target of your message could have just heard your tone of voice or seen your mischievous grin, they wouldn’t have taken it so seriously. This is why way back in 1982, the first emoticons were invented for use on ARPANET, the military sourced predecessor to the World Wide Web on the Internet. A computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University, Scott Fahlman used “:-)” to indicate sarcasm or humor and “:-(” to represent straightforward and serious tones.

Examples like these speak to the important contributions nonverbal communication makes to interactions.

Importance of Nonverbal Communication

Earlier in this book, we introduced the concept of “you cannot not communicate.” The foundation for this idea is that even though we may not be sending verbal messages, we are continually sending nonverbal messages. Moreover, we frequently do intend to convey meaning with our voices, and bodies, and faces. Whether those meanings come across can be another story. As such, it’s very important to understand how nonverbal messages impact our daily interpersonal interactions and lives.

Nonverbal Communication Provides Value for Meaning Making

It is hard to overestimate the meaning associated with nonverbal communication in any given interaction. For example, if you are having a conversation with your friend who just broke up with her girlfriend, you will use more than her words, “I just broke up with my girlfriend” to understand how to communicate with her. Your friend’s facial expression, way of standing, rate of speech, tone of voice, and general appearance, just to name a few, will indicate to you how you should respond. If she is sobbing, gasping for air, hunched over, and appears emotionally pained, you might attempt to comfort her. If she announces the breakup, sighs, and mocks wiping sweat off of her forehead, she might appear relieved. If you are aware and perceiving her cues, your response could reasonably be, “it seems like you may be a little relieved. Were things not going well?”

In addition to awareness, individuals may believe that nonverbal communication is valuable. If a parent ever said to you, “it wasn’t what you said, it was how you said it,” then they were demonstrating a belief that nonverbal communication is essential. If your best friend claimed that, “I can frown or shrug my shoulders without it meaning anything,” they would be devaluing nonverbal communication. As the recipient of the shoulder shrug, you know that, of course, it meant something, even if only to you. The indifference it conveys is no less powerful than a resigned, “whatever!”

Nonverbal Communication Can Be Ambiguous and Misunderstood

A particularly challenging aspect of nonverbal communication is the fact that it can be ambiguous. In the seventies, nonverbal communication was a trendy topic. Some were under the impression that we could use nonverbal communication to “read others like a book.” It was believed that anytime another person crossed her arms, she was always closed off to persuasion or communication. Also, that liars could be detected for their failure to make eye contact. These conclusions are only sometimes right, rather than infallible, and would be far more advisable if supported with verbal evidence.

Another great example of ambiguous nonverbal behavior is flirting! Consider some very stereotypical behavior of flirting (e.g., smiling, laughing, a light touch on the arm, or prolonged eye contact). Each of these behaviors may signal romantic interest or could be merely indicating desire for platonic friendship. However, Jeffrey Hall and Chong Xing of the University of Kansas Department of Communication Studies noted that particular nonverbal behaviors are more likely to associate with one of five different kinds of flirting styles.2 For instance, “sincere flirting” may involve less fidgeting and more smiling whereas “playful flirting” is often accompanied by extending or protruding of the chest.

Comedian Samuel J. Comroe has tremendous expertise in explaining how nonverbal communication can be misunderstood. His comedic routines focus on how Tourette’s syndrome affects his daily living. Tourette’s syndrome can change individual behavior, from uncontrolled body movements to uncontrolled vocalizations. Comroe often appears to be winking when he is not. He explains how his “wink” can cause others to believe he is joking when he isn’t. He also tells the story of how he met his wife in high school. During a skit, he played a criminal and she played a police officer. She told him to “freeze,” and he continued to move (due to Tourette’s). She misunderstood his movement to mean he was being defiant and thus “took him down.”

Nonverbal Communication Can Be Culturally Based or Universal

Successful interactions with individuals from other cultures are partially based on the ability to adapt to or understand their native nonverbal behaviors. One famous anecdote describes a merger meeting between representatives of an American and a Japanese company. Getting close to the deal that would link their firms together forever, the Americans shied off and backed out. It seems they noticed their counterparts giggling quietly to each other as the paperwork for signatures was passed around. Having grown up in a culture where giggling can signal others making fun of you, the Western businesspersons sensed that the potential partners were “putting one over” on them. Too bad none of them did their homework to discover that in some Eastern cultures, giggling is a sign of positive nervousness and anticipation.

While we should remember that noting the context of nonverbal communication may be critical to understanding it, there are some examples of cues that are nearly universal in meaning. For instance, a baby from virtually anywhere on Earth is just as likely to indicate mirth with a laugh and pain with a cry as any other infant.

Nonverbal Communication Is Omnipresent

Nonverbal communication is always present. Paul Watzlawick’s first axiom of his interactional view of communication asserts that humans cannot not communicate. Silence is an excellent example of nonverbal communication being omnipresent. Have you ever given someone the “silent treatment?” If so, you understand that by remaining silent, you are trying to convey some meaning, such as “You hurt me” or “I’m really upset with you.” In fact, even in the absence of that intention, your silence could be interpreted that way.

We can’t help but exude information that others can interpret. Asleep in the Brooklyn terminal awaiting his bus, Saul has no idea that others observe AND INTERPRET his nap (e.g., “that guy is tired”), his t-shirt (e.g., “wonder if he is ironically representing Def Leppard?”), and his extremely long beard and sidelocks (e.g., “he’s probably Hasidic”).

Nonverbal Communication Is Usually Trusted

Despite the pitfalls of nonverbal communication, individuals typically rely on nonverbal communication to identify the meaning in interactions. Communication scholars agree that the majority of meaning in any interaction is attributable to nonverbal communication. This is especially noteworthy when verbal and nonverbal cues are contradictory. You might assume that the expression, “well, excuse me,” when unaccompanied by nonverbals, would be a form of polite apology. Not so when entertainer Steve Martin’s nonverbals invested the expression with outrage and exasperation. In cases such as these, nonverbal communication tends to be believed more than verbal for meaning.

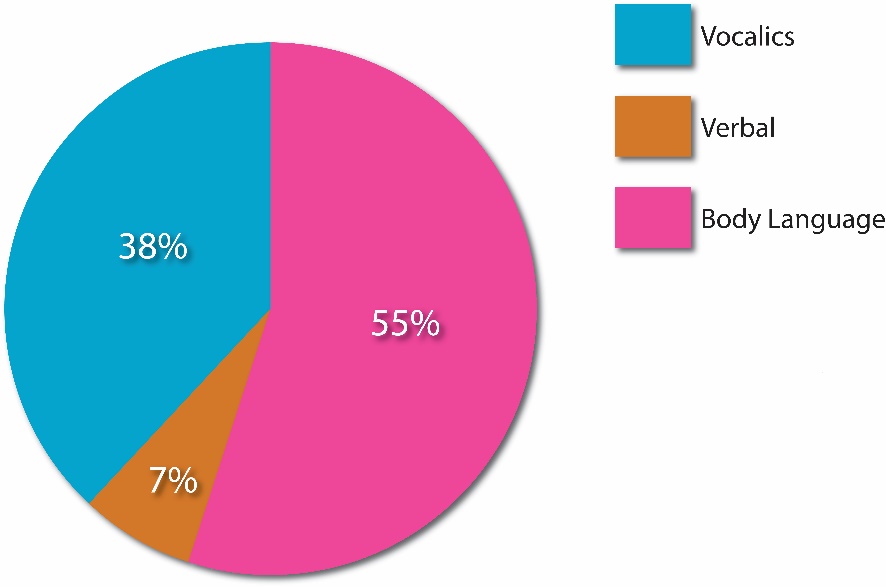

Some researchers find that meaning attributed to nonverbal communication in interactions ranges from 60 to 70%.3,4 Others have concluded that as much as 93% of meaning in any interaction is attributable to nonverbal communication. Albert Mehrabian asserts that this 93% of meaning can be broken into three parts (Figure 3).5

Regardless of the actual percentage, it is worth noting that the majority of meaning in interaction is deduced from nonverbal communication. But there are other functions served by nonverbal communication.

Key Takeaways

- Nonverbal communication is readily evident and important in everyday interactions.

- Nonverbal cues, even when unintentionally transmitted, help receivers derive meanings or decode verbal messages.

Exercises

- Create a list of three situations in which nonverbal communication helped you to accurately interpret verbal communication.

- When was the last time you felt like someone else’s true feelings were revealed by something other than their words?

Functions of Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal cues are used for a variety of purposes within everyday communication. More often than not, such usage is intentional, though we have already considered how nonverbal communication is not always within our volition.

Express Emotion

We use our arms, our tone of voice, and especially our faces, to show others how we are feeling. Watch Kansas City Royals third baseman George Brett’s reaction when the umpire calls him out, eliminating his supposed home run during the famous Pine Tar incident from a 1983 game against the New York Yankees. There is no doubt that Brett intended to register how furious he was at what he felt was an unfair, and uncalled for, ruling.

Sometimes, we do not intend to represent our true feelings but our nonverbals may give them away. In A Christmas Story, which has become a yuletide classic movie, Ralphie doesn’t want his parents to know the extent of his disappointment about not receiving the Red Ryder rifle he covets on Christmas morning. Yet, his slumped posture, downward gaze, and mumbled “Almost” in response to whether he got all he wanted all give him away. Within minutes, his unbridled joy at getting the gun after all is equally and unmistakeably evident.

Represent Meaning

As discussed below, nonverbals known as emblems can sometimes be used by their sources and receivers to arrive at clear and direct meanings. “Two thumbs pointed at this guy” indicate your own belief in some aspect of your identity just as pointing towards, but behind the back of, a culprit indicates their culpability in commiting some offense. Holding your hand straight out tells your friend to “stop!” arguing with you, while sticking your tongue out at her shows you didn’t appreciate the sarcastic insult she just delivered.

Inform Perceptions

Noverbals can be used to deliver messages to others about who or what we are. Flexing and pointing to a bicep or jutting out your chin and looking downward at your target can indicate that you are a tough guy who should not be messed with. Accidentally tripping over a Kilim rug in an antique shop and looking at it like it did it to you on purpose may give bystanders an entirely different, and humorous, impression of you.

Regulate Interaction

We can also inspire and shape our interactions with others through the mere display of particular nonverbal cues. Sticking out and waving your index fingers in the direction of your face tells another that you wish to chat with them while glancing at your watch frequently lets them know you have had about enough of their side of the story.

Key Takeaways

- Nonverbal communication serves many purposes.

- The functions of nonverbal communication are accomplished purposefully and unintentionally.

Channels of Nonverbal Communication

This chapter addresses several channels of nonverbal communication that are of particular importance in interpersonal relationships. These include haptics (touch), vocalics (voice), kinesics (body movement and gestures) including oculesics and facial expressions (eye and face behavior), proxemics (use of space) including nonverbal immediacy, artifacts (clothing and adornments), chronemics (use of time), olfactics (smell), and physical appearance. Each of these channels influences interpersonal communication and may have an impact on the success of interpersonal interactions.

Haptics

Haptics is the study of touch as a form of nonverbal communication. Touch is used in many ways in our daily lives, such as greeting, comfort, affection, task accomplishment, and control. Touch is a form of communication that can be used to initiate, regulate, and maintain relationships. Researchers state, “a handshake preceding social interactions positively influenced the way individuals evaluated the social interaction partners and their interest in further interactions while reversing the impact of negative impressions.”6

Several factors impact how touch is perceived and how individuals are evaluated in social interactions. These factors of touch are duration, frequency, intensity, and location.

Duration is how long touch endures; a hug from a seldom-seen auntie that lasts too long can be uncomfortable and induce dread about future contact with her. Frequency is how often touch is used; when a car sales person touches you again and again while invoking your name with every sentence, the artifice of those acts creates doubt about their good will towards you and damages their credibility. Intensity is the amount of pressure applied; a football quarterback may lean down hard on a running back’s shoulder pads in the huddle to emphasize holding onto the ball instead of fumbling it. Finally, location refers to the parts of the body that are touched; a suitor’s grazing of your hand means something very different than their cupping of your chin.

It’s also essential to understand the importance of touch to psychological wellbeing. Punyanunt-Carter and Wrench found that there are three different factors related to touch deprivation.7 First, the absence of touch is the degree to which an individual perceives that touch is not prevalent in their interactions. Second, a longing for touch can be psychologically straining because humans inherently have a desire for physical contact. Some address this void by petting their pets. Lastly, some people desire touch so much that they’ll engage in sexual activity just to get it. Punyanunt-Carter and Wrench also found a positive association between touch deprivation and depression and a negative one between touch deprivation and self-esteem.7

Vocalics

Vocalics are vocal utterances or characteristics, other than words, that serve as forms of communication. These include vocal characteristics such as pitch, tempo, and volume, as well as dysfluencies or vocal fillers.

Pitch

Pitch refers to placement on the frequency range between high and low and is the basis on which singing voices are classified as soprano, alto, tenor, baritone, or bass.

Pitch that changes or is is at a much higher or lower end of the range will be noticed. For example, when children become excited or scared, they may be described as “squealing.” However, when pitch is too static for too long, it is considered to be monotone and may be evaluated as droning and lifeless, especially in public speaking.

Tempo

Tempo refers to the rate at which one speaks. Extremes in tempo can reflect emotions such as excitement or anger, nervousness, or energy levels. When a diabetic aunt’s blood sugar is too low, she may start speaking slower, while an anxious salesperson may rush through a presentation to his bosses.

Volume

Volume refers to how loudly or softly an individual speaks. When individuals speak loudly, it may convey anger, emotional distress, happiness, or heightened excitement. When individuals speak at a lower volume, it could accompany the sharing of bad news, discussing of taboo or sensitive topics (i.e., when people whisper “sex” or “she died”), or conveying of private information.

Dysfluencies or Vocal Fillers

Dysfluencies or vocal fillers, are sounds that we make to fill dead air while we are thinking of what to say next. In the United States, “um” or “uh” are the most commonly used dysfluencies. In conversation, these dysfluencies may pass unnoticed by both the sender or receiver, but they may be distracting when a public speaker says “uh” or “um” repetitively.

Kinesics

Kinesics is the study of how the body is used in communication and includes facial expressions, eye behaviors, posture, and gestures.

Facial Expressions

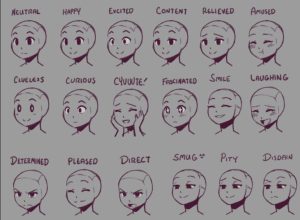

Facial expressions are one form of kinesics. Paul Eckman and Wallace V. Friesen asserted that facial expressions are likely to communicate seven emotions that are recognized throughout the world.8 These emotions are often referred to by the acronym S.A.D.F.I.S.H. and include Surprise, Anger, Disgust, Fear, Interest, Sadness, and Happiness. It is pretty incredible how small changes in facial muscles can be read by others as indicating nuanced emotions such as contentment, smugness, and disdain (see Figure 4).

Although not all facial expression is “universally” recognized, people are generally able to interpret facial expressions within a context. Smiling might communicate happiness, politeness, or a desire to be pleasing. When a flight attendant pastes on a smile while dealing with a difficult passenger, observers are unlikely to register that as actual happiness.

Oculesics

Oculesics is the study of how individuals communicate through eye behavior. Eye contact is generally the first form of communication for interactants. In situations where people are looking to find partners, such as at a Sadie Hawkins dance, some will intepret the sharing of eye contact as a sign of romantic interest.

Often when discussing eye behavior, researchers refer to “gaze.” Research consistently demonstrates that females gaze at interaction partners more frequently than males9,10,11 and that when people gaze for too long or for too little, there is likely to be a negative interpretation of this behavior.12 Gaze is sometimes the focus (little pun intended) of interesting contextual and cultural implications. An Iranian-American employee may be told by bosses to “look at me when I’m talking to you” because they were socialized to avert eye contact with superiors. Conversely, subordinates may be told when dressed down by their Navy drill sergeant to “stop eyeballing me!”

Posture

Posture refers to the shape of our bodies when standing or sitting and varies from curved and slouched to erect and straight. Strong posture may be associated with interest, formality, or respect while weak posture can signal disinterest, fatigue, or boredom. Military superiors often command their charges to stand at attention or to adopt the “at ease” position.

Gestures

Gestures are movements of the body, especially the arms and hands, that convey meaning. Gestures that differ in the functions they serve are known as emblems, illustrators, affect displays, and regulators.

Emblems

Gestures that are are clear and unambiguous and have a verbal equivalent in a given culture are called emblems.13 The Smashmouth lyric in All Star: “She was looking kind of dumb with her finger and her thumb in the shape of an L on her forehead” portrays use of the emblem for “loser.” A few emblematic gestures seem to be universal, such as a shrug of the shoulders for “I don’t know.” Many of them are culturally determined, meaning that they may mean different things in different places. In the United States, the thumbs-up and “okay” hand gestures are positive but in Iran, Ethiopia, and Mexico, they may have negative sexual connotations or even be considered obscene.14

Illustrators

While emblems can be used as direct substitutions for words, illustrators are kinesics that help emphasize or explain a word. Arms spread way out with hands held parallel illustrate how “big the fish that got away was” and shaking a fist while shouting at an inconsiderate driver helps to get across anger.

Affect Displays

Affect displays are nonverbal cues that show feelings and emotions. Sure, a frown shows sadness and a smile gladness. But how about fans of the National Hockey League’s 2023-2024 Florida Panthers, who were so thrilled with the team’s first Stanley Cup championship that they literally shook the glass and boards that surround their home ice? Ironically, an hour earlier, the same glass was pounded loudly to express disgust with a referee’s missed interference call.

Regulators

Regulators, as discussed earlier, are gestures like head nods and eye contact that help initiate, coordinate, or terminate the flow of conversational turn taking. Listeners may sit back but shift forward when wanting to speak. Quick and furtive glances at the clock on the wall may signal a desire to wrap up an interaction.

Proxemics

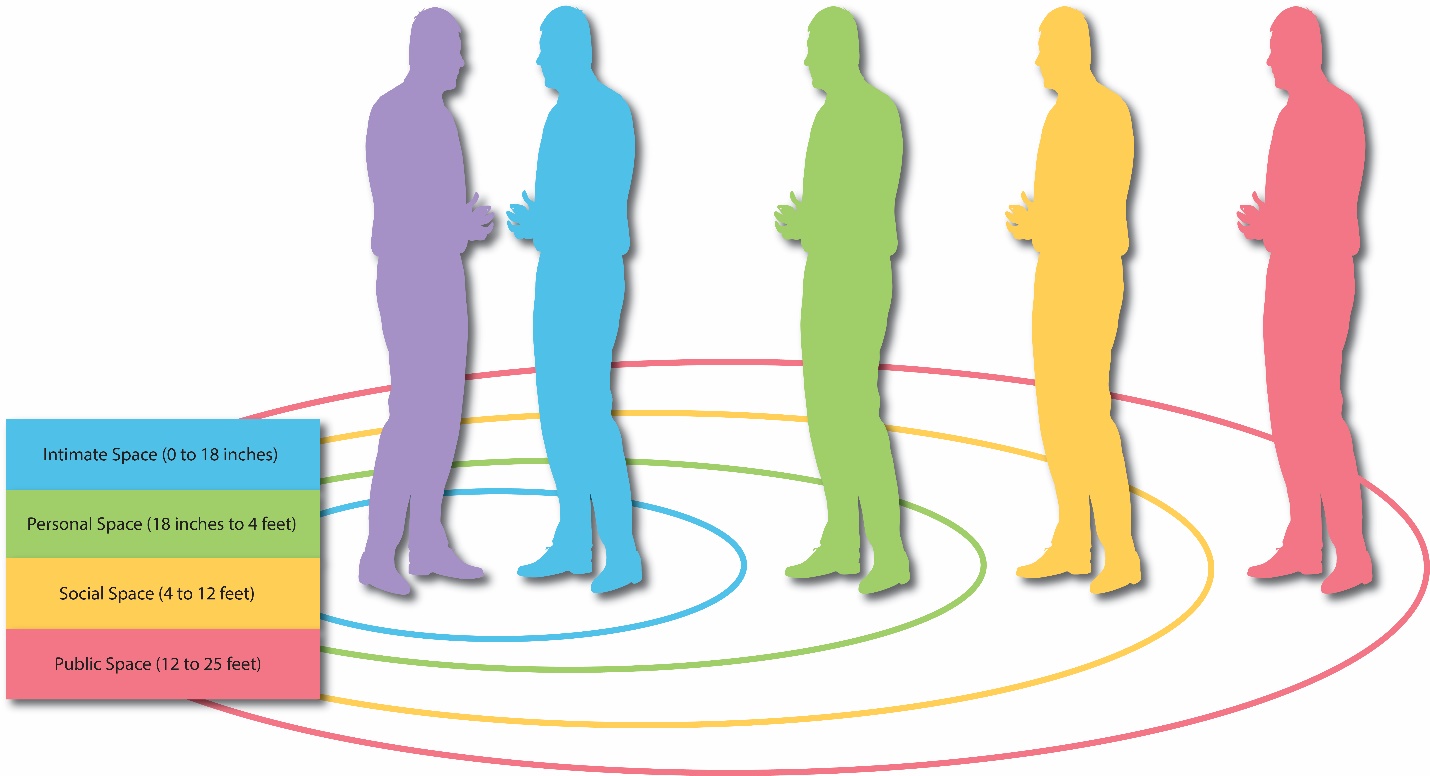

Proxemics is the study of communication through the use and understanding of physical space. Supermarkets and business offices may be arranged to influence sales or symbolize status, for instance. Space between communicators was famously categorized by Edward T. Hall,15 who recognized four approximated “distances” used to achieve comfort in conversation. These distances are sometimes referred to as “space bubbles” (see Figure 5).

Hall’s largest bubble, from 12 feet to 25 feet away, is referred to as “public” distance, often adopted in contexts such as public speaking. Social distance, anywhere from 4 to 12 feet, is meant for acquaintances, such as vaguely familar coworkers and fellow elevator riders. The personal distance, 18 inches to 4 feet, is often used for conversations with friends or some family. Intimate distance, that ranges between 0 and 18 inches from the body, is reserved for those with whom we have our closest personal relationships. Moms, BFFs, and significant others are comfortably allowed this close to us.

The actual space associated with each distance is likely to vary with personal preferences and cultural contexts. Jerry, his parents, and Kramer strugle to cope with the proxemics style of a friend who is a “close talker” on the sitcom, Seinfeld. Riders of the Tokyo Metro train system must accept intimate distance with strangers on cars that are packed densely with people, like sardines in a can. Check out “Professional Pushers Shove Passengers Onto Busy Tokyo Train!“

Nonverbal Immediacy

Nonverbal immediacy is defined as physical and/or psychological closeness. More specifically, Mehrabian defines immediacy as behaviors increasing the sensory stimulation between individuals.16 Immediacy behaviors include being physically close and oriented toward another, eye contact, some touch, gesturing, vocal variety, and talking louder. Immediacy behaviors are known to be impactful in a variety of contexts.

In instructional, organizational, and social contexts, research has revealed powerful positive impacts attributable to immediacy behaviors, including influence and compliance, liking, relationship satisfaction, job satisfaction, and learning. In the health care setting, the positive outcomes of nonverbally immediate interaction are well documented: patient satisfaction,17,18 understanding of medical information,19,20 patient perceptions of provider credibility,21 patient perceptions of confidentiality,22 and decreased apprehension when communicating with a physician.23

Artifacts

Artifacts are items with which we adorn our bodies with or carry with us. These include tattoos and piercings, jewelry, clothing, or any object that communicates meaning. One very famous artifact that most most recognize is the eyeglasses of Harry Potter. When Snoop Dogg was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, he wore a classic camel hair overcoat, but also large bulky jewelry. These accoutrements could be interpreted as classy and rebellious or tasteful and showy. Their contrasts might even signify the extent of Snoop’s confidence due to his wealth, fame, and power.

Chronemics

Chronemics, as explained by Thomas J. Bruneau,24 is the meaning(s) of time and use of it to communicate. As with many nonverbals, chronemics are sometimes culturally bound. Cultures using monochronic time prefer engaging in one task at a time and those using polychronic time multitask more. Traditionally, the U.S. is a monochronic culture along with Canada or Northern Europe whereas Korea, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa tend to be more polychronic. Time is a bit more fluid in polychronic cultures and punctuality is more important in monochronic ones.

Olfactics

Olfactics generally refers to the study of scent and communication. Scent can draw others in or repel them, and the same scent can have different impacts on different people. Fragrances like cologne and perfume, and shower and bath products are billion dollar industries in the United States. The summer of 2024 saw a huge wave on social media of testimonials for the pleasing santal and bergamot scents of Salt and Stone, a natural deodorant.

Countless articles in the popular media address how to deal with a “smelly coworker” while others describe the sexual attractiveness we perceive from another’s pheremones, chemicals emitted from their glands. A terrific bit of evidence for the idiosyncratic nature of communication is that the alluring appeal of your cologne to one person may be an overwhelming cloud of olfactory assault to another.

Physical Appearance

Whether we like it or not, our physical appearance has an impact on how people view, and relate to, us. Physical appearance is often among the reasons people decide whether to interact with each other.

Dany Ivy and Sean Wahl argue that physical appearance is a very important factor in nonverbal communication:

The connection between physical appearance and nonverbal communication needs to be made for two important reasons: (1) The decisions we make to maintain or alter our physical appearance reveal a great deal about who we are, and (2) the physical appearance of other people impacts our perception of them, how we communicate with them, how approachable they are, how attractive or unattractive they are, and so on.25

In fact, people ascribe all kinds of meanings based on their perceptions of how we physically appear to them. Everything from your height, skin tone, smile, weight, and hairstyle can communicate meanings to other people.

Physical Appearance and Society

Unfortunately for people considered to be less attractive and for society at large, research has shown physical appearance to affect outcomes and lives in different specific ways:

- Physically attractive students are viewed as more popular by their peers.

- Physically attractive people are seen as smarter.

- Physically attractive job applicants are more likely to get hired.

- Physically attractive people make more money.

- Physically attractive journalists are seen as more likable and credible.

- Physically attractive defendants in a court case were less likely to be convicted, and if they were convicted, the juries recommended less harsh sentences.

Culture and era matter in how physical attractiveness is assessed. For example, the “Rubenesque ideal” for physical attractiveness was a dominant standard centuries ago. It stems from the paintings of Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), who is famous for his use of full-figured women to depict beauty(see Figure 6).

In the United States today, most people that are portrayed in leading roles are thin and fit. In Rubens’ time, they might have been considered to be frail and even poor, as evidenced by their apparent undernourishment.

Facial symmetry, the extent to which the two sides of a face mirror each other, is considered a prominent contemporary determinant of attractiveness, as well.

The Matching Hypothesis

One obvious area where physical appearance plays a huge part in our day-to-day lives is in our romantic relationships. Elaine Walster and her colleagues coined the “matching hypothesis” in the 1960s.26,27 The basic premise of the matching hypothesis is that the idea of “opposites attracting” really doesn’t pertain to physical attraction. When all else is equal, people are more likely to find themselves in romantic relationships with people who are perceived as similarly physically attractive.

In a classic study conducted by Shepherd and Ellis, the researchers took pictures of married couples and mixed up the images of the husbands and wives.28 The researchers then had groups of female and male college students sort the images based on physical attraction. Not surprisingly, there was a positive relationship between the physical attractiveness of the men and women who were matched.

Overall, research generally supports the matching hypothesis as a factor that impacts dating selection ability, but physical attractiveness is not the only variable that can impact romantic partners (e.g., socioeconomic status, education, career prospects).

Key Takeaways

- Nonverbal channels of communication are informed by many parts of our bodies and our voices..

- Vocal cues such as rate, pitch, and volume have an impact on whether communication is effective.

- Facial expressions and body movements may enhance communication, but they also may contradict words or unintentionally reveal feelings.

Exercises

Key Terms

affect displays

Nonverbal cues that show feelings and emotions.

artifacts

Items with which we adorn our bodies with or carry with us.

chronemics

The meaning(s) of time and use of it to communicate.

dysfluencies

Vocal fillers or sounds that we make to fill dead air while we are thinking of what to say next.

emblems

Gestures that are are clear and unambiguous and have a verbal equivalent in a given culture.

gestures

Movements of the body, especially the arms and hands, that convey meaning.

haptics

The study of touch as a form of communication.

illustrators

Kinesics that emphasize or explain a word.

kinesics

The study of how the body is used in communication and includes facial expressions, eye behaviors, posture, and gestures.

matching hypothesis

A prediction that people are more likely to find themselves in romantic relationships with people who are perceived as similarly physically attractive.

monotone

The quality of voice that features virtually no change in pitch and may be evaluated as droning and lifeless.

nonverbal communication

Communication that is produced by some means other than words such as eye contact, body language, or vocal cues.

nonverbal immediacy

Physical and/or psychological closeness.

oculesics

The study of how individuals communicate through eye behavior.

olfactics

The study of scent and communication.

pitch

Placement on the frequency range between high and low and is the basis on which singing voices are classified as soprano, alto, tenor, baritone, or bass.

posture

The shape of our bodies when standing or sitting and varies from curved and slouched to erect and straight.

proxemics

The study of communication through the use and understanding of physical space.

regulators

Gestures like head nods and eye contact that help initiate, coordinate, or terminate the flow of conversational turn taking.

tempo

The rate of speech; how slowly or quickly you talk.

vocalics

Vocal utterances or characteristics, other than words, such as pitch, tempo, and volume, that serve as forms of communication.

volume

How loudly or softly an individual speaks.

Notes

Communication that is produced by some means other than words such as eye contact, body language, or vocal cues.

The study of touch as a form of communication.

The placement of your voice on the musical scale; the basis on which singing voices are classified as soprano, alto, tenor, baritone, or bass voices.

(pronounced “TAM-ber”) The overall quality and tone, which is often called the “color” of your voice; the primary vocal quality that makes your voice either pleasant or disturbing to listen to.

The rate of your speech; how slowly or quickly you talk.

How loudly or softly an individual speaks.

Vocal fillers or sounds that we make to fill dead air while we are thinking of what to say next.

The study of how the body is used in communication and includes facial expressions, eye behaviors, posture, and gestures.

The study of how individuals communicate through eye behavior.

The shape of our bodies when standing or sitting and varies from curved and slouched to erect and straight.

Movements of the body, especially the arms and hands, that convey meaning.

Gestures that are are clear and unambiguous and have a verbal equivalent in a given culture.

Kinesics that emphasize or explain a word.

Nonverbal cues that show feelings and emotions.

Gestures like head nods and eye contact that help initiate, coordinate, or terminate the flow of conversational turn taking.

The study of communication through the use and understanding of physical space.

Physical and/or psychological closeness.

Items with which we adorn our bodies with or carry with us.

The meaning(s) of time and use of it to communicate.

The study of scent and communication.

A prediction that people are more likely to find themselves in romantic relationships with people who are perceived as similarly physically attractive.