Talking and Listening

Learning Objectives

- Learn different types of conversation.

- Describe the motivations and consequences of self-disclosure and the Johari Window.

- Understand how to listen effectively and the different types of listening.

- Discuss different types of listening responses and types of questions.

We are constantly interacting with people. We interact with our family and friends. We interact with our teachers and peers at school. We interact with customer service representatives, office coworkers, physicians/therapists, and so many other different people in average day. Humans are inherently social beings, so talking and listening to each other is a huge part of what we all do day-to-day.

The Importance of Everyday Conversations

Most of us spend a great deal of our day interacting with other people through what is known as a conversation. According to Judy Apps, the word “conversation” is comprised of the words con (with) and versare (turn): “conversation is turn and turnabout – you alternate.”1 As such, a conversation isn’t a monologue or singular speech act; it’s a dyadic process where two people engage with one another in interaction that has multiple turns. Philosophers have been writing about the notion of the term “conversation” and its importance in society since the written word began.2 Conversation is an important part of the interpersonal experience. Through conversations with others, we can build, maintain, and terminate relationships.

Coming up with an academic definition for the term “conversation” is not an easy task. For our purposes, we prefer Susan Brennan’s definition: “Conversation is a joint activity in which two or more participants use linguistic forms and nonverbal signals to communicate interactively.”4 Conversations are one of the most common forms of interpersonal communication.

Types of Conversations

David Angle argues that conversations can be categorized based on directionality (one-way or two-way) and tone/purpose (cooperative or competitive).8 One-way conversations are conversations where an individual is talking at the other person and not with the other person. Although these exchanges are technically conversations because of the inclusion of nonverbal feedback, one of the conversational partners tends to monopolize the bulk of the conversation while the other partner is more of a passive receiver. Two-way conversations, on the other hand, are conversations where there is mutual involvement and interaction. In two-way conversations, people are actively talking, providing nonverbal feedback, and listening.

In addition to one vs. two-way interactions, Angle also believes that conversations can be broken down on whether they are cooperative or competitive. Cooperative conversations are marked by a mutual interest in what all parties within the conversation have to contribute. Conversely, individuals in competitive conversations are more concerned with their points of view than others within the conversation. Angle further breaks down his typology of conversations into four distinct types of conversation (Figure 1).

Discourse

The first type of conversation is one-way cooperative, which Angle labeled discourse. The purpose of a discourse conversation is for the sender to transmit information to the receiver. For example, a professor delivering a lecture or a speaker giving a speech.

Dialogue

The second type is what most people consider to be a traditional conversation: the dialogue (two-way, cooperative). According to Angle, “The goal is for participants to exchange information and build relationships with one another.”9 When you go on a first date, the general purpose of most of our conversations in this context is dialogue. If conversations take on one of the other three types, you could find yourself not getting a second date.

Debate

The third type of conversation is the two-way, competitive conversation, which Angle labels “debate.” The debate conversation is less about information giving and more about persuading. From this perspective, debate conversations occur when the ultimate goal of the conversation is to win an argument or persuade someone to change their thoughts, values, beliefs, and behaviors. Imagine you’re sitting in a study group and you’re trying to advocate for a specific approach to your group’s project. In this case, your goal is to persuade the others within the conversation to your point-of-view.

Diatribe

Lastly, Angle discusses the diatribe (one-way, competitive). The goal of the diatribe conversation is “to express emotions, browbeat those that disagree with you, and/or inspires those that share the same perspective.”10 For example, imagine that your best friend has come over to your dorm room, apartment, or house to vent about the grade they received on a test.

Sharing Personal Information

One of the primary functions of conversations is sharing information about ourselves. Earlier in the book, we discussed Berger and Calabrese’s Uncertainty Reduction Theory (URT).11 One of the basic axioms of URT is that, as verbal communication increases between people when they first meet, the level of uncertainty decreases. Specifically, the type of verbal communication generally discussed in initial interactions is called self-disclosure.12 Self-disclosure is the process of purposefully communicating information about one’s self. Sidney Jourard sums up self-disclosure as permitting one’s “true self” to be known to others.13

As we introduce the concept of self-disclosure in this section, it’s important to realize that there is no right or wrong way to self-disclose. Different people self-disclose for a wide range of different reasons and purposes. Emmi Ignatius and Marja Kokkonen found that self-disclosure can vary for several reasons:14

- Personality traits (shy people self-disclose less than extraverted people)

- Cultural background (Western cultures disclose more than Eastern cultures)

- Emotional state (happy people self-disclose more than sad or depressed people)

- Biological sex (females self-disclose more than males)

- Psychological gender (androgynous people were more emotionally aware, topically involved, and invested in their interactions; feminine individuals disclosed more in social situations, and masculine individuals generally did not demonstrate meaningful self-disclosure across contexts)

- Status differential (lower status individuals are more likely to self-disclose personal information than higher-status individuals)

- Physical environment (soft, warm rooms encourage self-disclosure while hard, cold rooms discourage self-disclosure)

- Physical contact (touch can increase self-disclosure, unless the other person feels that their personal space is being invaded, which can decrease self-disclosure)

- Communication channel (people often feel more comfortable self-disclosing when they’re not face-to-face; e.g., on the telephone or through computer-mediated communication)

As you can see, there are quite a few things that can impact how self-disclosure happens when people are interacting during interpersonal encounters.

Motives for Self-Disclosure

So, what ultimately motivates someone to self-disclose? Emmi Ignatius and Marja Kokkonen found two basic reasons for self-disclosure: social integration and impression management.15

Social Integration

The first reason people self-disclose information about themselves is simply to develop interpersonal relationships. Part of forming an interpersonal relationship is seeking to demonstrate that we have commonality with another person. For example, let’s say that it’s the beginning of a new semester, and you’re sitting next to someone you’ve never met before. You quickly strike up a conversation while you’re waiting for the professor to show up. During those first few moments of talking, you’re going to try to establish some kind of commonality. Maybe you’ll learn that you’re both communication majors or that you have the same favorite sports team or band. Self-disclosure helps us find these areas where we have similar interests, beliefs, values, attitudes, etc.… As humans, we have an innate desire to be social and meet people. And research has shown us that self-disclosure is positively related to liking.16 The more we self-disclose to others, the more they like us and vice versa.

However, we should mention that appropriate versus inappropriate self-disclosures depends on the nature of your relationship. When we first meet someone, we do not expect that person to start self-disclosing their deepest darkest secrets. When this happens, then we experience an expectancy violation. Judee Burgoon conceptualized expectancy violation theory as an understanding of what happens when an individual within an interpersonal interaction violates the norms for that interaction.17,18 Burgoon’s original expectancy violation theory (EVT) primarily analyzed what happened when individuals communicated nonverbally in a manner that was unexpected (e.g., standing too close while talking). Over the years, EVT has been expanded by many scholars to look at a range of different situations when communication expectations are violated.19 As a whole, EVT predicts that when individuals violate the norms of communication during an interaction, they will evaluate that interaction negatively. However, this does depend on the nature of the initial relationship. If we’ve been in a relationship with someone for a long time or if it’s someone we want to be in a relationship with, we’re more likely to overlook expectancy violations.

So, how does this relate to self-disclosure? Mostly, there are ways that we self-disclose that are considered “normal” during different types of interactions and contexts. What you disclose to your best friend will be different than what you disclose to a stranger at the bus station. What you disclose to your therapist will be different than what you disclose to your professor. When you meet a stranger, the types of self-disclosure tend to be reasonably common topics: your major, sports teams, bands, the weather, etc. If, however, you decide to self-disclose information that is overly personal, this would be perceived as a violation of the types of topics that are normally disclosed during initial interactions. As such, the other person is probably going to try to get out of that conversation pretty quickly. When people disclose information that is inappropriate to the context, those interactions will generally be viewed more negatively.20

From a psychological standpoint, finding these commonalities with others helps reinforce our self-concept. We find that others share the same interests, beliefs, values, attitudes, etc., which demonstrates that how we think, feel, and behave are similar to those around us. Admittedly, it’s not like we do all of this consciously.21

Impression Management

The second reason we tend to self-disclose is to portray a specific impression of who we are as individuals to others. Impression management is defined as “the attempt to generate as favorable an impression of ourselves as possible, particularly through both verbal and nonverbal techniques of self-presentation.”22 Basically, we want people to view us in a specific way, so we communicate with others in an attempt to get others to see us that way. Research has found we commonly use six impression management techniques during interpersonal interactions: self-descriptions, accounts, apologies, entitlements and enhancements, flattery, and favors.23,24

Self-Disclosure

- The type of relationship will affect individuals’ need to disclose.

- The disclosure has a risk-to-benefits ratio. In other words, individuals, who disclose certain types of information, may risk losing certain things (i.e., career or pride) or may benefit certain things (i.e., trust or security).

- The appropriateness and relevance to the situation impacts what gets disclosed and what does not get disclosed.

- Disclosure depends on reciprocity. Individuals will disclose similar amounts of information to each other.

Social Penetration Theory

In 1973, Irwin Altman and Dalmas Taylor were interested in discovering how individuals become closer to each other.32 They believed that the method of self-disclosure was similar to social penetration and hence created the social penetration theory. This theory helps to explain how individuals gradually become more intimate based on their communication behaviors. According to the social penetration theory, relationships begin when individuals share non-intimate layers and move to more intimate layers of personal information.33

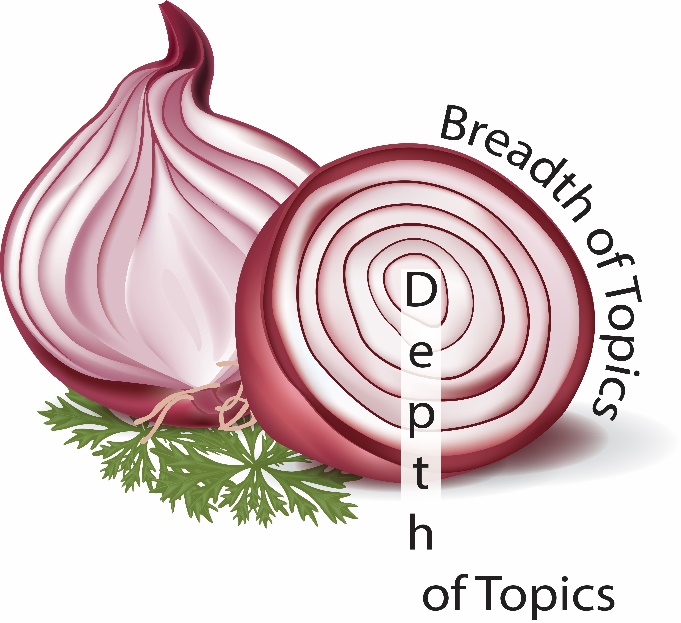

Altman and Taylor believed that individuals discover more about others through self-disclosure. How people comprehend others on a deeper level helps us also gain a better understanding of ourselves. The researchers believe that penetration happens gradually. The scholars describe their theory visually like an onion with many rings or levels.34 A person’s personality is like an onion because it has many layers (Figure 2). We have an outer layer that everyone can see (e.g., hair color or height), and we have very personal layers that people cannot see (e.g., our dreams and career aspirations).

Three factors affect what people chose to disclose.

- The first is personal characteristics (e.g., introverted or extraverted).

- The second is the possibility of any reward or cost with disclosing to the other person (e.g., information might have repercussions if the receiver does not like or agree with you).

- The third is the situational context (e.g., telling your romantic partner that you want to terminate the relationship on your wedding day).

When people first meet each other, they start from their outer rings and slowly move towards the core. People typically go through various stages to become closer.

- The first stage is called the orientation stage, where people communicate on very superficial matters like the weather.

- The next stage is the exploratory affective stage, where people will disclose more about their feelings about normal topics like favorite foods or movies. Many of our friendships remain at this stage.

- The third stage is more personal and called the affective stage, where people engage in more private topics.

- The fourth stage is the stable stage, where people will share their most intimate details.

- The last stage is not obligatory and does not necessarily happen in every relationship, it is the depenetration stage, where people start to decrease their disclosures.

Social penetration theory also contains two different aspects. The first aspect is breadth, which refers to what topics individuals are willing to talk about with others. For instance, some people do not like to talk about religion and politics because it is considered inappropriate. The second aspect is depth, which refers to how deep a person is willing to go in discussing certain topics. For example, some people don’t mind sharing information about themselves in regards to their favorite things. Still, they may not be willing to share their most private thoughts about themselves because it is too personal. By self-disclosing to others both in breadth and depth, it could lead to more relational closeness.

Johari Window

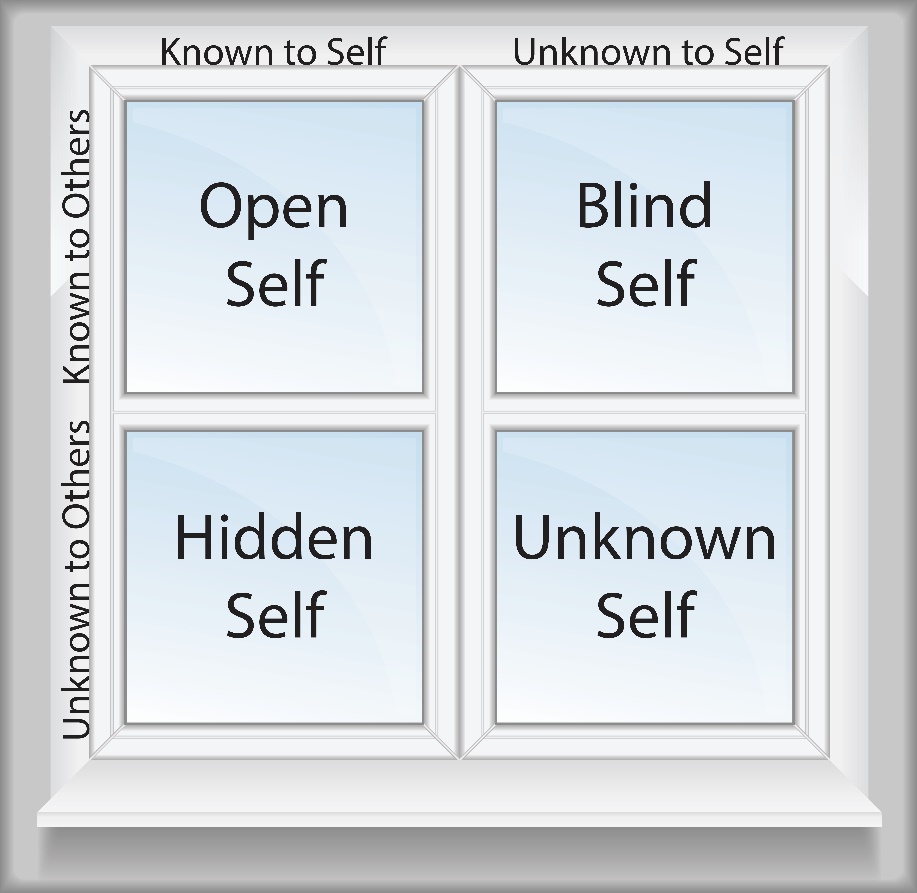

The name “Johari” is a combination of the two researchers who originated the concept: Joseph Luft (Jo) and Harrington Ingham (hari).35 The basic idea behind the Johari Window is that we build trust in our interpersonal relationships as we self-disclose revealing information about ourselves, and we learn more about ourselves as we receive feedback from the people with whom we are interacting.

As you can see in Figure 3, the Johari Window is represented by four window panes. Two window panes refer to ourselves, and two refer to others. First, when discussing ourselves, we have to be aware that somethings about ourselves are known to us, and others are not. For example, we may be completely aware of the fact that we are extraverted and love talking to people (known to self). However, we may not be aware of how others tend to view our extraversion as positive or negative (unknown to self). The second part of the window is what is known to others and unknown to others. For example, some common information known to others includes your height, weight, hair color, etc. At the same time, there is a bunch of information that people don’t know about us: deepest desires, joys, goals in life, etc. Ultimately, the Johari Window breaks this into four different quadrants (Figure 3).

Open Self

The first quadrant of the Johari Window is the open self, or when information is known to both ourselves and others. Although some facets are automatically known, others become known as we disclose more and more information about ourselves with others. As we get to know people and self-disclose and increasingly deeper levels, the open self quadrant grows. For the purposes of thinking about discussions and self-disclosures, the open self is where the bulk of this work ultimately occurs.

Information in the open self can include your attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, emotions/feelings, experiences, and values that are known to both the person and to others. For example, if you wear a religious symbol around your neck (Christian Cross, Jewish Start of David, Islamic Crescent Moon and Star, etc.), people will be able to ascertain certain facts about your religious beliefs immediately.

Hidden Self

The second quadrant is what is known to ourselves but is not known to others. All of us have personal information we may not feel compelled to reveal to others. For example, if you’re a member of the LGBTQIA+ community, you may not feel the need to come out during your first encounter with someone new. It’s also possible that you’ll keep this information from your friends and family for a long time.

Think about your own life, what types of things do you keep hidden from others? One of the reasons we keep things hidden is because it’s hard to open ourselves up to being vulnerable. Typically, the hidden self will decrease as a relationship grows. However, if someone ever violates our trust and discusses our hidden self with others, we are less likely to keep disclosing this information in the future. If the trust violation is extreme enough, we may discontinue that relationship altogether.

Blind Self

The third quadrant is called the blind self because it’s what we don’t know about ourselves that is known by others. For example, during an initial interaction, we may not know how the other person is reacting to us. We may think that we’re coming off as friendly, but the other person may be perceiving us as shy or even pushy. One way to decrease the blind self is by soliciting feedback from others. As others reveal more of our blind selves, we can become more self-aware of how others perceive us.

One problem with the blind self is that how people view us and how we view ourselves can often be radically different. For example, people may perceive you as cocky, but in reality, you’re scared to death. It’s important to decrease the blind self during our interactions with others, because how people view us will determine how they interact with us.

Unknown Self

Lastly, we have the unknown self, or when information is not known by ourselves or others. The unknown self can include aptitudes/talents, attitudes/feelings, behaviors, capabilities, etc. that are unknown to us or others. For example, you may have a natural talent to play the piano. Still, if you’ve never sat down in front of a piano, neither you nor others would have any way of knowing that you have the aptitude/talent for playing the piano. Sometimes parts of the unknown self are just under the surface and will arise with time and in the right contexts, but other times no one will ever know these unknown parts.

One other area that can affect the unknown self involves prior experiences. It’s possible that you experienced a traumatic event that closes you down in a specific area. For example, imagine that you are an amazing writer, but someone, when you were in the fourth grade, made fun of a story you wrote, so you never tried writing again. In this case, the aptitude/talent for writing has been stamped out because of that one traumatic experience as a child. Sadly, a lot of us probably have a range of aptitudes/talents, attitudes/feelings, behaviors, capabilities, etc. that were stopped because of traumas throughout our lives.

Key Takeaways

- We self-disclose to share information with others. It allows us to express our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

- Self-disclosure includes levels of disclosure, reciprocity in disclosure, and appropriate disclosure.

- There can be positive and negative consequences of self-disclosure. These consequences can strengthen how you feel or create distance between you and someone else.

- The Johari Window is a model that helps to illustrate self-disclosure and the process by which you interact with other people.

Listening

When it comes to daily communication, we spend about 45% of our listening, 30% speaking, 16% reading, and 9% writing.36 However, most people are not entirely sure what the word “listening” is or how to do it effectively.

Hearing Is Not Listening

Hearing refers to a passive activity where an individual perceives sound by detecting vibrations through an ear. Hearing is a physiological process that is continuously happening. We are bombarded by sounds all the time. Unless you are in a sound-proof room or are 100% deaf, we are constantly hearing sounds. Even in a sound-proof room, other sounds that are normally not heard like a beating heart or breathing will become more apparent as a result of the blocked background noise.

Listening, on the other hand, is generally seen as an active process. Listening is “focused, concentrated attention for the purpose of understanding the meanings expressed by a [source].”37 From this perspective, hearing is more of an automatic response when your ear perceives information; whereas, listening is what happens when we purposefully attend to different messages.

We can even take this a step further and differentiate normal listening from critical listening. Critical listening is the “careful, systematic thinking and reasoning to see whether a message makes sense in light of factual evidence.”38 From this perspective, it’s one thing to attend to someone’s message, but something very different to analyze what the person is saying based on known facts and evidence.

Let’s apply these ideas to a typical interpersonal situation. Let’s say that you and your best friend are having dinner at a crowded restaurant. Your ear is going to be attending to a lot of different messages all the time in that environment, but most of those messages get filtered out as “background noise,” or information we don’t listen to at all. Maybe then your favorite song comes on the speaker system the restaurant is playing, and you and your best friend both attend to the song (listening) because you both like it. Let’s say you and your friend start to discuss campus parking. Your friend states, “There’s never any parking on campus. What gives?” Now, if you’re critically listening to what your friend says, you’ll question the basis of this argument. For example, the word “never” in this statement is problematic because it would mean that the campus has zero available parking, which is probably not the case. Now, it may be difficult for your friend to find a parking spot on campus, but that doesn’t mean that there’s “never any parking.” In this case, you’ve gone from just listening to critically evaluating the argument your friend is making.

Model of Listening

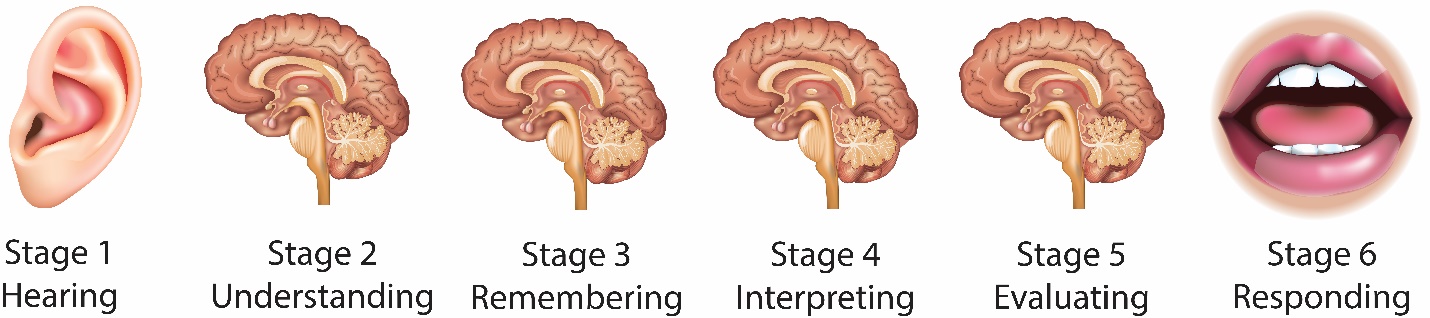

Judi Brownell created one of the most commonly used models for listening.39 Although not the only model of listening that exists, we like this model because it breaks the process of listening down into clearly differentiated stages: hearing, understanding, remembering, interpreting, evaluating, and responding (Figure 4).

Hearing

From a fundamental perspective, for listening to occur, an individual must attend to some kind of communicated message. Now, one can argue that hearing should not be equated with listening (as we did above), but it is the first step in the model of listening. Simply, if we don’t attend to the message at all, then communication never occurred from the receiver’s perspective.

Imagine you’re standing in a crowded bar with your friends on a Friday night. You see your friend Darry and yell her name. In that instant, you, as a source of a message, have attempted to send a message. If Darry is too far away, or if the bar is too loud and she doesn’t hear you call her name, then Darry has not engaged in stage one of the listening model. You may have tried to initiate communication, but the receiver, Darry, did not know that you initiated communication.

Understanding

The second stage of the listening model is understanding, or the ability to comprehend or decode the source’s message. When we discussed the basic models of human communication earlier in the book, we discussed the idea of decoding a message. Simply, decoding is when we attempt to break down the message we’ve heard into comprehensible meanings. For example, imagine someone coming up to you asking if you know, “Tintinnabulation of vacillating pendulums in inverted, metallic resonant cups.” Even if you recognize all of the words, you may not completely comprehend what the person is even trying to say. In this case, you cannot decode the message. Just as an FYI, that means “jingle bells.”

Remembering

Once we’ve decoded a message, we have to actually remember the message itself, or the ability to recall a message that was sent. We are bombarded by messages throughout our day, so it’s completely possible to attend to a message and decode it and then forget it about two seconds later. It is challenging to remember everything.

For example, if you tell your professor something when they are leaving the class, they may forget it quickly as they switch gear to their next class. It is wise to email them important things, so they don’t forget. The remembering process fails people all the time. This problem plagues all of us.

Interpreting

The next stage in the HURIER Model of Listening is interpreting. “Interpreting messages involves attention to all of the various speaker and contextual variables that provide a background for accurately perceived messages.”40 So, what do we mean by contextual variables? A lot of the interpreting process is being aware of the nonverbal cues (both oral and physical) that accompany a message to accurately assign meaning to the message.

Imagine you’re having a conversation with one of your peers, and he says, “I love math.” Well, the text itself is demonstrating an overwhelming joy and calculating mathematical problems. However, if the message is accompanied by an eye roll or is said in a manner that makes it sound sarcastic, then the meaning of the oral phrase changes. Part of interpreting a message then is being sensitive to nonverbal cues.

Evaluating

The next stage is the evaluating stage, or judging the message itself. One of the biggest hurdles many people have with listening is the evaluative stage. Our personal biases, values, and beliefs can prevent us from effectively listening to someone else’s message.

Let’s imagine that you despise a specific politician. It’s gotten to the point where if you hear this politician’s voice, you immediately change the television channel. Even hearing other people talk about this politician causes you to tune out completely. In this case, your own bias against this politician prevents you from effectively listening to their message or even others’ messages involving this politician. Overcoming our own biases against the source of a message or the content of a message in an effort to truly listen to a message is not easy. One of the reasons listening is a difficult process is because of our inherent desire to evaluate people and ideas.

Responding

In Figure 4, hearing is represented by an ear, the brain represents the next four stages, and a person’s mouth represents the final stage. Effective listening starts with the ear and centers in the brain. Only then should someone provide feedback to the message itself. Often, people jump from hearing and understanding to responding, which can cause problems as they jump to conclusions that have arisen by truncated interpretation and evaluation.

Ultimately, how we respond to a source’s message will dictate how the rest of that interaction will progress. If we outright dismiss what someone is saying, we put up a roadblock that says, “I don’t want to hear anything else.” On the other hand, if we nod our heads and say, “tell me more,” then we are encouraging the speaker to continue the interaction. For effective communication to occur, it’s essential to consider how our responses will impact the other person and our relationship with that other person.

Listening Styles

Now that we have a better understanding of how listening works, let’s talk about four different styles of listening researchers have identified. Kittie Watson, Larry Barker, and James Weaver defined listening styles as “attitudes, beliefs, and predispositions about the how, where, when, who, and what of the information reception and encoding process.”44 Watson et al. identified four distinct listening styles: people, content, action, and time.

The Four Listening Styles

People

The first listening style is the people-oriented listening style. People-oriented listeners tend to be more focused on the person sending the message than the content of the message. As such, people-oriented listeners focus on the emotional states of senders of information. One way to think about people-oriented listeners is to see them as highly compassionate, empathic, and sensitive, which allows them to put themselves in the shoes of the person sending the message.

People-oriented listeners often work well in helping professions where listening to the person and understanding their feelings is very important (e.g., therapist, counselor, social worker, etc.). People-oriented listeners are also very focused on maintaining relationships, so they are good at casual conservation where they can focus on the person.

Action

The second listening style is the action-oriented listener. Action-oriented listeners are focused on what the source wants. The action-oriented listener wants a source to get to the point quickly. Instead of long, drawn-out lectures, the action-oriented speaker would prefer quick bullet points that get to what the source desires. Action-oriented listeners “tend to preference speakers that construct organized, direct, and logical presentations.”46

When dealing with an action-oriented listener, it’s important to realize that they want you to be logical and get to the point. One of the things action-oriented listeners commonly do is search for errors and inconsistencies in someone’s message, so it’s important to be organized and have your facts straight.

Content

The third type of listener is the content-oriented listener, or a listener who focuses on the content of the message and process that message in a systematic way. Of the four different listening styles, content-oriented listeners are more adept at listening to complex information. Content-oriented listeners “believe it is important to listen fully to a speaker’s message prior to forming an opinion about it (while action listeners tend to become frustrated if the speaker is ‘wasting time’).”47

When it comes to analyzing messages, content-oriented listeners really want to dig into the message itself. They want as much information as possible in order to make the best evaluation of the message. As such, “they want to look at the time, the place, the people, the who, the what, the where, the when, the how … all of that. They don’t want to leave anything out.”48

Time

The final listening style is the time-oriented listening style. Time-oriented listeners are sometimes referred to as “clock watchers” because they’re always in a hurry and want a source of a message to speed things up a bit. Time-oriented listeners “tend to verbalize the limited amount of time they are willing or able to devote to listening and are likely to interrupt others and openly signal disinterest.”49

They often feel that they are overwhelmed by so many different tasks that need to be completed (whether real or not), so they usually try to accomplish multiple tasks while they are listening to a source. Of course, multitasking often leads to someone’s attention being divided, and information being missed.

Thinking about the Four Listening Types

It’s possible to be a combination of different listening styles. However, some of the listening style combinations are more common. For example, someone who is action-oriented and time-oriented will want the bare-bones information so they can make a decision. On the other hand, it’s hard to be a people-oriented listener and time-oriented listener because being empathic and attending to someone’s feelings takes time and effort.

Key Takeaways

- Hearing happens when sound waves hit our eardrums. Listening involves processing these sounds into something meaningful.

- The listening process includes: having the motivation to listen, clearly hearing the message, paying attention, interpreting the message, evaluating the message, remembering and responding appropriately.

- There are different types of listening styles: people, action, content, and time.

Listening Responses

Who do you think is a great listener? Why did you name that particular person? How can you tell that person is a good listener? You probably recognize a good listener based on the nonverbal and verbal cues that they display. In this section, we will discuss different types of listening responses. We all don’t listen in the same way. Also, each situation is different and requires a distinct style that is appropriate for that situation.

Types of Listening Responses

Adler and colleagues have found different types of listening responses: silent listening, questioning, paraphrasing, empathizing, supporting, analyzing, evaluating, and advising (Figure 6).53

Silent Listening

Silent listening occurs when you say nothing. It is ideal in certain situations and awful in other situations. However, when used correctly, it can be very powerful. If misused, you could give the wrong impression to someone. It is appropriate to use when you don’t want to encourage more talking. It also shows that you are open to the speaker’s ideas.

Sometimes people get angry when someone doesn’t respond. They might think that this person is not listening or trying to avoid the situation. But it might be due to the fact that the person is just trying to gather their thoughts, or perhaps it would be inappropriate to respond. There are certain situations such as in counseling, where silent listening can be beneficial because it can help that person figure out their feelings and emotions.

Questioning

In situations where you want to get answers, it might be beneficial to use questioning. You can do this in a variety of ways. There are several ways to question in a sincere, nondirective way (see Table 3):

| Reason | Example |

|---|---|

| To clarify meanings | A young child might mumble something and you want to make sure you understand what they said. |

| To learn about others’ thoughts, feelings, and wants (open/closed questions) | When you ask your partner where they see your relationship going in the next few years. |

| To encourage elaboration | Nathan says “That’s interesting!” Jonna has to ask him further if he means interesting in a positive or negative way. |

| To encourage discovery | Ask your parents how they met because you never knew. |

| To gather more facts and details | Police officers at the scene of the crime will question any witnesses to get a better understanding of what happened. |

Table 3 Types of Nondirective Questioning

You might have different types of questions. Sincere questions are ones that are created to find a genuine answer. Counterfeit questions are disguised attempts to send a message, not to receive one. Sometimes, counterfeit questions can cause the listener to be defensive. For instance, if someone asks you, “Tell me how often you used crystal meth.” The speaker implies that you have used meth, even though that has not been established. A speaker can use questions that make statements by emphasizing specific words or phrases, stating an opinion or feeling on the subject. They can ask questions that carry hidden agendas, like “Do you have $5?” because the person would like to borrow that money. Some questions seek “correct” answers. For instance, when a friend says, “Do I look fat?” You probably have a correct or ideal answer. There are questions that are based on unchecked assumptions. An example would be, “Why aren’t you listening?” This example implies that the person wasn’t listening, when in fact they are listening.

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is defined as restating in your own words, the message you think the speaker just sent. There are three types of paraphrasing. First, you can change the speaker’s wording to indicate what you think they meant. Second, you can offer an example of what you think the speaker is talking about. Third, you can reflect on the underlying theme of a speaker’s remarks. Paraphrasing represents mindful listening in the way that you are trying to analyze and understand the speaker’s information. Paraphrasing can be used to summarize facts and to gain consensus in essential discussions. This could be used in a business meeting to make sure that all details were discussed and agreed upon. Paraphrasing can also be used to understand personal information more accurately. Think about being in a counselor’s office. Counselors often paraphrase information to understand better exactly how you are feeling and to be able to analyze the information better.

Empathizing

Empathizing is used to show that you identify with a speaker’s information. You put yourself in their shoes to understand the situation. You are not empathizing when you deny others the rights to their feelings. Examples of this are statements such as, “It’s really not a big deal” or “Who cares?” This indicates that the listener is trying to make the speaker feel a different way. In minimizing the significance of the situation, you are interpreting the situation in your perspective and passing judgment.

Supporting

Sometimes, in a discussion, people want to know how you feel about them instead of a reflection on the content. Several types of supportive responses are: agreement, offers to help, praise, reassurance, and diversion. The value of receiving support when faced with personal problems is very important. This has been shown to enhance psychological, physical, and relational health. To effectively support others, you must meet certain criteria. You have to make sure that your expression of support is sincere, be sure that other person can accept your support, and focus on “here and now” rather than “then and there.”

Analyzing

Analyzing is helpful in gaining different alternatives and perspectives by offering an interpretation of the speaker’s message. However, this can be problematic at times. Sometimes the speaker might not be able to understand your perspective or may become more confused by accepting it. To avoid this, steps must be taken in advance. These include tentatively offering your interpretation instead of as an absolute fact. By being more sensitive about it, it might be more comfortable for the speaker to accept. You can also make sure that your analysis has a reasonable chance of being correct. If it were inaccurate, it would leave the person more confused than before. Also, you must make sure the person will be receptive to your analysis and that your motive for offering is to truly help the other person. An analysis offered under any other circumstances is useless.

Evaluating

Evaluating appraises the speaker’s thoughts or behaviors. The evaluation can be favorable (“That makes sense”) or negative (passing judgment). Negative evaluations can be critical or non-critical (constructive criticism). Two conditions offer the best chance for evaluations to be received: if the person with the problem requested an evaluation, and if it is genuinely constructive and not designed as a putdown.

Advising

Advising differs from evaluations. It is not always the best solution and can sometimes be harmful. In order to avoid this, you must make sure four conditions are present: be sure the person is receptive to your suggestions, make sure they are truly ready to accept it, be confident in the correctness of your advice, and be sure the receiver won’t blame you if it doesn’t work out.

Research Spotlight

In 2015, Karina J. Lloyd, Diana Boer, Avraham N. Kluger, and Sven C. Voelpel conducted an experiment to examine the relationship between perceived listening trust and wellbeing. In this study, the researchers recruited pairs of strangers. They had one of the participants tell the other about a positive experience in their life for seven minutes (the talker) and one who sat and listened to the story without comment (the listener).

In 2015, Karina J. Lloyd, Diana Boer, Avraham N. Kluger, and Sven C. Voelpel conducted an experiment to examine the relationship between perceived listening trust and wellbeing. In this study, the researchers recruited pairs of strangers. They had one of the participants tell the other about a positive experience in their life for seven minutes (the talker) and one who sat and listened to the story without comment (the listener).

The researchers found that talkers who perceived the listener to be listening intently to be very important for effective communication. First, perceived listening led to a greater sense of social attraction towards the listener, which in turn, led to a greater sense of trust for the listener. Second, talkers who perceived the listener as listening intently felt their messages were clearer, which in turn, led to a greater sense of the talker’s overall wellbeing (positive affect).

As you can see, simply perceiving that the other person is listening intently to you is very important on a number of fronts. For this reason, it’s very important to remember to focus your attention when you’re listening to someone.

Lloyd, K. J., Boer, D., Kluger, A. N., & Voelpel, S. C. (2015). Building trust and feeling well: Examining intraindividual and interpersonal outcomes and underlying mechanisms of listening. International Journal of Listening, 29(1), 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.2014.928211

Perception Checking

To judge others more accurately, we need to engage in perception checking.

Perception checking involves three steps:

- Describe your perception of the event

- Offer three different interpretations of that behavior

- Seek clarification about the interpretations

That’s it! I know this sounds easy, but it’s definitely much harder than it looks.

Key Takeaways

- The different types of listening responses are silent listening, questioning, paraphrasing, empathizing, supporting, analyzing, evaluating, and advising.

- Questioning can be to clarify meanings, encourage elaboration, learn about others, increase discovery, or obtain more information.

- Perception checking involves describing the situation, offering three possible interpretations, and then seeking information.

Key Terms

analyzing

This is helpful in gaining different alternatives and perspectives by offering an interpretation of the speaker’s message.

communication motives

Reasons why we communicate with others.

conversations

Interpersonal interactions through which you share facts and information as well as your ideas, thoughts, and feelings with other people.

empathizing

This is used to show that you identify with the speaker’s information.

hearing

A passive activity where an individual perceives sound by detecting vibrations through an ear.

Johari window

A model that illustrates self-disclosure and the process by which you interact with other people.

listening

A complex psychological process that can be defined as the process of physically hearing, interpreting that sound, and understanding the significance of it.

paraphrase

To restate what another person said using different words.

self-disclosure

The act of verbally or nonverbally revealing information about yourself to other people.

silent listening

This occurs when you say nothing and is appropriate for certain situations.

social penetration theory

Theory originally created by Altman and Taylor to explain how individuals gradually become more intimate as individuals self-disclose more and those self-disclosures become more intimate (deep).

Chapter Wrap-Up

We spend most of our lives engaged in talking and listening behavior. As such, understanding the functions of talking and listening in interpersonal communication is very important. In this chapter, we started by discussing the importance of everyday conversations. We next discussed a specific type of talk: disclosing information about ourselves (self-disclosure). We then switched gears and focused on the listening component. Overall, talking and listening are extremely important to interpersonal communication, so understanding how they function can help improve our communication skills.

Notes

a dyadic communication interaction process where two people engage with one another in interaction that has multiple turns

conversations where an individual is talking at the other person and not with the other person

conversations where there is mutual involvement and interaction between conversation partners

Conversations which involve mutual interest in what all parties within the conversation have to contribute

Conversations where parties are more concerned with their points of view than others within the conversation

The process of sharing information with another person.

An understanding of what happens when an individual within an interpersonal interaction violates the norms for that interaction.

"The attempt to generate as favorable an impression of ourselves as possible, particularly through both verbal and nonverbal techniques of self-presentation."

Theory originally created by Altman and Taylor to explain how individuals gradually become more intimate as individuals self-disclose more and those self-disclosures become more intimate (deep).

Amount various topics discussed.

How deep or intensely a topic is discussed.

A passive activity where an individual perceives sound by detecting vibrations through an ear.

A complex psychological process that can be defined as the process of physically hearing, interpreting that sound, and understanding the significance of it.

To analyze what the person is saying based on known facts and evidence.

This occurs when you say nothing and is appropriate for certain situations.

To restate what another person said using different words.

This is used to show that you identify with the speaker’s information.

This is helpful in gaining different alternatives and perspectives by offering an interpretation of the speaker’s message.