Introduction to Communication

Learning Objectives

- Describe reasons to study communication.

- Identify needs that communication fulfills.

- Name six principles of communication.

- Differentiate among the elements of communication processes and communication models.

- Define eight types of communication.

- Understand and apply the nine statements of communication ethics.

Communication Defined

If you’re like most people taking their first course or reading their first book in communication, you may be wondering what it is that you’re going to be studying. Academics like interpersonal communication scholars are notorious for not agreeing on definitions of concepts. We like to think of communication as the process by which messages representing information, meaning, and emotion are sent and received between two or more people. Interpersonal communication, is communication between a small number of people that is the essence of relationships and often face-to-face and synchronous.

Mark Knapp and John Daly have identified several issues of contention commonly found in attempts to define and delineate interpersonal communication: number of communicators involved, the physical proximity of the communicators, and degree of formality and structure.1

Number of Communicators Involved

Some scholars argue that interaction within one dyad is the best representation of interpersonal communication as it promotes clear distinction from small group or organizational communication. But most agree that interpersonal communication involves “at least two communicators.” It does not seem right to include a negotiation between brothers as an example and then exclude it if a sister gets involved, too.

Physical Proximity of the Communicators

In a lot of early writing on the subject of interpersonal communication, researchers argued that interpersonal communication is a face-to-face endeavor. However, with the range of mediated technologies we have in the 21st Century, we often communicate interpersonally with people through social networking sites, text messaging, email, the phone, and a range of other technologies. Is the interaction between two lovers as they break up via text messages any less “interpersonal” than when the break up happens face-to-face?

Degree of Formality and Structure

A great deal of research in interpersonal communication has focused on interpersonal interactions that are considered informal and unstructured (e.g., friendships, romantic relationships, family interactions, etc.). However, many interpersonal interactions have a greater degree of formality and structure associated with them. For example, meeting with your physician at the student health center or with your supervisor at work calls for many interpersonal communication skills and behaviors, though these interactions have more norms and restrictions than chatting with a buddy.

Why Study Communication?

Most people think they are great communicators. However, very few people are “naturally” good at it. Communication takes time, skill, and practice. To be a great communicator, you must also be a great listener. It requires some proficiency and competence. Think about someone you know that is not a good communicator. Why is that person not good at it? Do they say things that are inappropriate, rude, or hostile? Are you confused whenthey get done talking? This text is designed to give you the skills to be a better communicator.

Reasons to Study Communication

There are several great rationales for learning about, researching, teaching, and studying communication. Morreale and Pearson believe that there are three main reasons why we need to study communication.2 First is that we spend a very large portion of our time communicating with other people. Within this book, we make the claim that we cannot not communicate. It is practically pervasive in our lives. Human beings are social creatures and we crave, or even need, relationships and interaction, with others.

The second reason is that when you study communication it gives you a new perspective on something you might otherwise take for granted. Communication majors are often asked why they study communication when it is something everybody knows how to do naturally. In fact, when subjected to scrutiny, the ways that people choose to communicate can be surprising and fascinating. How is your professor so good at speaking for an hour without notes and seemingly without fear? Why can’t your boss see that demeaning and berating their employees reduces their productivity?

Third, since most people do not realize how often they are ineffective at communicating, or how many choices they have for doing it, a great reason to study communication is to improve at it!

Communication Needs

What does it mean to say that we need communication with others? We benefit from communication in ways that protect and improve: our physical, mental, emotional, and social health; our identities; and, our accomplishment of everyday and longer range goals.

Health

Interaction with others can bring joy and fulfillment, which contribute positively to our social lives and general well being. Relationships, especially those well-steeped in communication, generally improve our emotional and social health. KU alumnus Joy Koesten analyzed family communication patterns and found that people who grew up in higher conversation oriented families were more likely to have better relationships than people who grew up in lower conversation oriented families.3 In another study, Stafford and Canary illustrated the importance of communication in dating relationships.4

Adler and colleagues found that communication decreases:5

- Stress

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Cancer

- Coronary problems

- Common Cold Symptoms

Studies show that people who encounter negative experiences and communicate about them with others are more likely to have better mental and physical health.6 Social psychologist James Pennebaker’s entire research paradigm demonstrates that putting our stresses, upsets, and fears into words, even if we are merely imagining an audience for them, is likely to heighten moods, reduce health care visits, and even improve immune system responses!7

Finally, when you feel that your health is diminished or threatened, you can attempt to restore or maintain it by soliciting help from others, like friends or doctors, by telling them and seeking help.

Identity

Communication helps us discover who we are. From a very young age, you were probably presented with a variety of characteristics about your physical appearance and your personality. You might have been told that you are funny, intelligent, pretty, friendly, talented, or insightful. Others may hear that they are not very smart, out of shape, or lazy. Charles Cooley’s concept of the looking glass self recognizes our self-images are shaped by how others act around, and speak to, us as well as by what we inherently know about ourselves. 8 It is as though the people we are surrounded by provide us information about ourselves just like a mirror we look into.

Figure 2. Looking Glass Self. “Man takes a picture of himself and wife in a mirror.” by simpleinsomnia. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Success

There are a nearly infinite number of goals that we pursue in social settings. At any one time, you might look to influence a customer to buy, inform a colleague about an event, soothe an upset nephew, or resolve a conflict between your current and former romantic partners. Communication is the means for accomplishing such goals as we operate socially.

By studying communication, we learn to assess situations, analyze others, and choose appropriate messages to attain success. We also learn about the cornucopia of tactics and strategies for designing the messages. To deal with your partner’s jealousy, some of your many options include to bring it up directly, ask questions about it, share a related story, wait until they are less upset, or even choose to not bring it up at all.

Those who are especially skilled communicators may be able to deliver messages that are responsive to multiple goals they have for an interaction. An elementary school teacher often looks to keep her students engaged by being entertaining while also being sure to convey the information in a lesson plan.

Exercises

- Why do you think it is important to study communication? Is this class required for you? Do you think it should be a requirement for everyone?

- Think about how your identity has been shaped by others. What is something that was said to you that impacted how you felt? How do you feel now about the comment?

Basic Principles of Communication

Following are six basic principles about communication that illuminate what it is and how it happens. These include that communication is a process, purposeful, multidimensional, contextual, and cultural, and can be more or less competent.

Communication Is a Process

The word “process” refers to the idea that something is ongoing, dynamic, and changing with a purpose or towards some end. A communication scholar named David K. Berlo was the first to discuss human communication as a process back in 1960.9 From Berlo’s perspective, communication is a series of ongoing interactions that change over time. For example, think about the number of “inside jokes” you may have with your best friend. Sometimes you can get to the point where all you say is one word, and both of you crack up laughing. This level of familiarity and short-hand communication didn’t exist when you first met but has developed over time.

Communication Is Purposeful

There are occasions where our interpersonal communication is not intentional. Sometimes, we are overheard by others without realizing it. Even though you did not mean to convey these meanings, people may ascertain that you are sleepy in class, by observing your posture and narrowed eyelids, or excited at the poker table, due to your widely-opened eyes. These are examples of the nonverbal communication covered in a later chapter.

However, the vast majority of our communication is intentional and with purpose. As noted above, human beings communicate for different reasons, including the achievement of goals like relating, persuading, and comforting. We employ messages in the effort to create the desired outcomes.

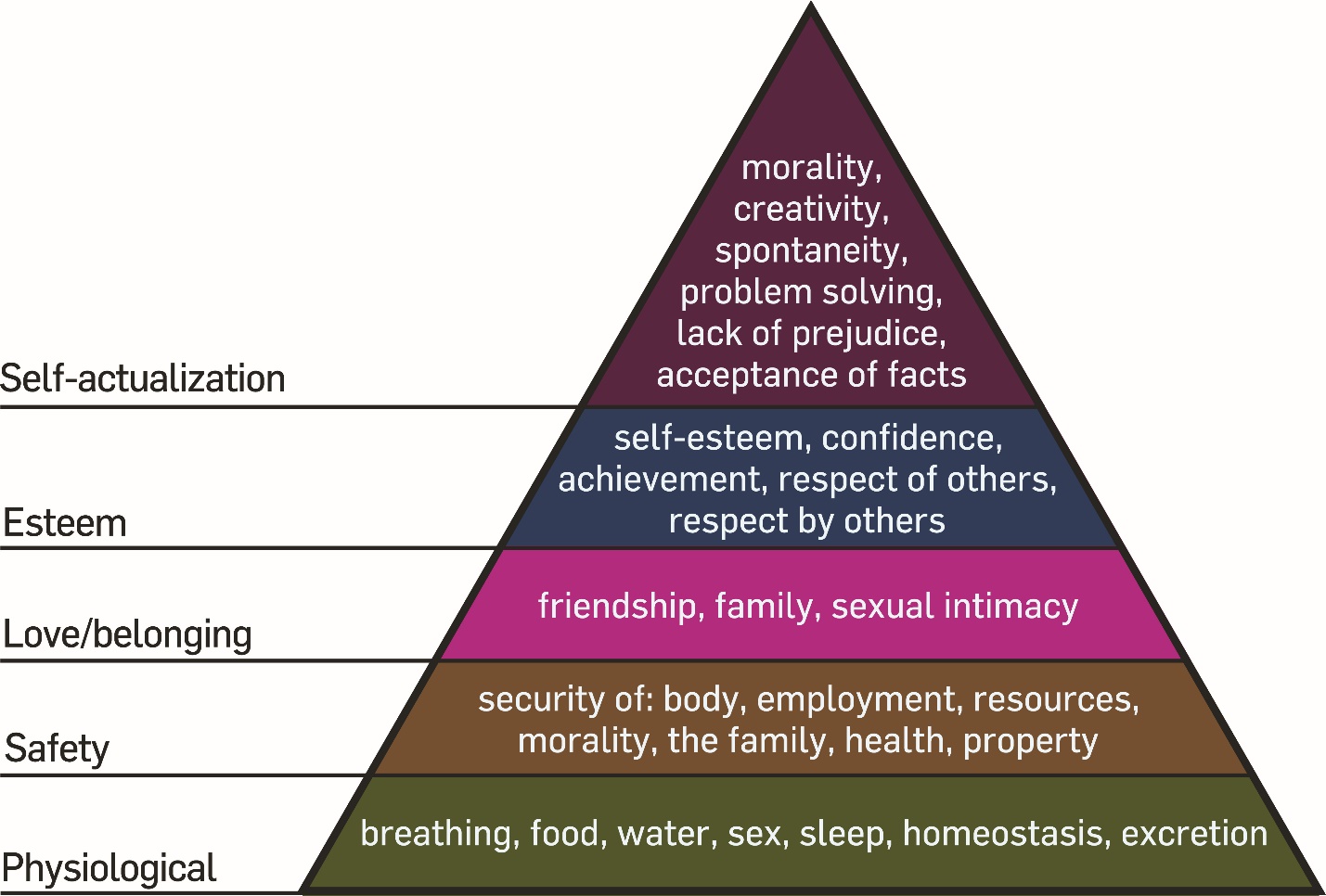

Another perspective for considering communication as a means to ends is found with examination of Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.10 Following knowledge he learned while working with the Blackfoot Native Nation in Canada, Maslow argued that human needs emerge in order starting from the bottom of the pyramid shown in Figure 3. At the basic level, humans must have physiological needs met, such as breathing, food, water, and sleep. Once the physiological needs have been met, humans can attempt to meet safety needs, which involve security about maintaining employment, health, and access to resources. Having the first two levels satisfied, we strive for love and belonging, which encompasses friendship, intimacy, and membership in social structures like families and clubs. The higher-order needs begin with esteem, which includes self respect, achievement, and status within our social groups. Finally, self-actualization pertains to fulfilling potential and reaching ideals.

With full consciousness or even in less explicit fashion, it is common for individuals to aid their ascension through Maslow’s Hierarchy with communication. Whether you are pursuing a sexual encounter by using a pickup line, reaching out to a disappointed client to keep your job, or coaching your team to a winning record, your messages serve the climb up the pyramid. For two decades starting in 1980, the United States Army recruited soldiers by appealing to their visions of self-actualization with the slogan, “Army. Be All You Can Be.”

Communication Is Multidimensional

When we communicate with other people, our messages and meanings exist in multiple realms. Any given interaction or message, or even sentence, can be said to have three different sides to it. Those sides are the instrumental, relational, and identity dimensions.

The instrumental dimension refers to the most literal aspects such as informative content and goal-driven intent. The relational dimension includes ways in which this interaction is influenced by, and continues to shape, the nature of the relationship between the interactants. There are often also factors and impacts of our communication that affect how we are regarded and they make up the identity dimension. So, for instance, the message, “I can’t handle this, so it’s up to you to have the discussion with Dad about where he will live after Mom is gone,” assigns a task to a sibling receiver (i.e., instrumental), leads the family dynamics in potentially negative directions (i.e., relational) , and portrays the source as incapable in some way (i.e., identity).

Communication Is Contextual

The circumstance, environment, setting, situation and/or history between parties surround an interaction. The choices made within, and impacts of, a conversation will be informed by all of these contextual elements. The calm measured instructions offered by a troop leader during training exercises may be replaced by their loud, urgent, and profane commands in the dangerous heat of battle. Having failed due to lack of preparation every time you appealed to Professor Smythe, you might approach them this time armed with far more examples and rationales for a grade change.

Communication Is Cultural

The word culture refers to a “group of people who through a process of learning can share perceptions of the world that influences their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.”11 We learn culture from our families, our schools, our peers, our religions, and our nations. It ultimately influences what we believe, what we value, what we consider “normal,” and what rules we live by. Each of these impact how we interact and behave with others. This influence is often emphasized when we deal with someone from a culture that differs from ours, which is known as intercultural communication.

At a local Ethiopian restaurant, you express interest in some strips of meat or stew, so the server recommends tibs and doro wot. Your friend Merrill, seated next to you, suddenly blurts out their concern about the price of gasoline. A little embarrassed, you remark, “Gee, that came out of left field.” As Americans steeped in baseball culture, you get this idiom that refers to anything random or unanticipated. Your confused Ethiopian waiter, raised in rural Mosebo Village, asks, “Why cannot the gas come from the right or middle field?”

One of the most interesting things about studying communication is locating the origins of misunderstandings and intercultural differences are common culprits. Then again, interacting and relating with people different than yourself can be some of the most exciting and rewarding communication you will ever have.

Communication Is Sometimes Competent

Brian Spitzberg claims that communication competence occurs when communication is both appropriate and effective.12 Appropriate communication includes tactics and behaviors that most people would consider acceptable and ethical. Effective communication achieves the goal(s) at least one party had for an interaction.

Competent communicators are generally more likely to achieve their communication goals. They are more skilled than others at being able to listen, explain, comfort, persuade, etc. and better than most at selecting strategies and tactics that best fit situations. They are also adaptable so that they can change their approach when things aren’t going well, from a bored conversational partner to a technology failure during a presentation. Competent communicators understand the motivations and preferences of those they interact with so they can construct the most effective and appropriate messages. This may take extra effort such as researching, analyzing, and observing one’s audience.

To achieve communication competence usually takes some measure of cognitive complexity, which means seeing the world from multiple perspectives but with nuance, too. A cognitively complex person is good at identifying many characteristics about others and adopting others’ perspectives in order to adapt messages to them.13 For instance a person who is cognitively complex would be likely to provide concern, comfort, and explanation to an employee they must let go, rather than just fire them outright. This is because they can imagine what it would be like to be in the other’s shoes, what that person might want most to hear, and how to formulate that into the most sensitive and useful messaging.

Perhaps as important for communication competence is emotional intelligence (EQ), the ability to recognize your own emotions and the emotions of others.14 EQ is highly associated with empathy for others and workplace success.

Finally, producers of communication competence are probably accomplished and balanced self-monitors. Self-monitoring is the ability to focus on and recognize your own behavior, including communication. Those who pay attention to what they say and do are more likely to act how they prefer to. Competent communicators have to achieve a balance of high and low self-monitoring, so that they realize how they are perceived without being too self-centered to also focus on others.

Exercises

- Discuss the possibility that the levels of the pyramid indicating Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs could be sought simultaneously or even in reverse order.

- Who do you think are competent/incompetent communicators? Why?

Elements of Communication

Some people think that communication is easy. In reality, more often than not, communication is hard to perform and difficult to understand. Have you ever tried to contact a company to dispute a subscription charge you never authorized? Good luck! With a large proportion of communicative attempts to achieve goals turning out to be ineffective or worse, it is highly instructive to figure out how and why interpersonal communication can go awry.

To understand and fix what is wrong with a sluggish car engine, a loud refrigerator, a pixelated TV screen, or a sick body, a diagnostic approach is best. We can study communication the same way we study other systems and processes. Just as a mechanic or a doctor would inspect the parts of the engine or the patient and figure out which ones were not operating properly, so can communication scholars. By analyzing the different elements of communication, we can understand how it works, why it sometimes fails to work, and what to diagnose to solve similar problems. The elements of communication, that are almost always present in any single interaction are: source, receiver, message, channel, environment, feedback, and noise.

Source

The sourceis the person who decides to communicate, identifies the intent of the message (entertain, inform, distract), and constructs its content. Source is synonymous, and often used interchangeably, with sender . Senders or sources draw from feelings, thoughts, perceptions, language capabilities, past experiences, and communication skill sets to design their messages. The process by which sources formulate their thoughts into verbal or nonverbal messages is known as “encoding.” As you experience your desire to add sodium chloride to your bland green beans, you might inquire, “Uncle Jim, could you please pass me the salt?”

Sources usually decide about ways to deliver their message such as softly or louder, quickly or slower, and either stoically or with elaborate gesturing.

Receiver

The receiver(s) is the individual who decodes the message and tries to understand the source of the message and the meaning they intended. Receivers may use any of their five senses to detect and experience messages. They naturally filter messages based on their attitudes, beliefs, opinions, values, history, and prejudices. The process of perception, presented in the next chapter, is vital to the reception and interpretation of a source’s messages. Your eyesight allows you to see street maintenance workers waving at you near a manhole repair and decide that they would like you to drive around it. If you had never before been in a moving car, you might jump to some other incorrect conclusion.

Message

A message is the information, meaning, and/or emotion conveyed by verbal or nonverbal means, the content of a communication interaction. People send messages intentionally (texting a friend to meet for coffee) or unintentionally (accidentally falling asleep during a live Ted Talk). Messages can be verbal (saying hello to your neighbors), nonverbal (gymnast McKayla Maroney smirking with indifference to winning only a silver medal), or text (an admirer sliding into your DMs). Messages are usually the basis of meaning, as they provide information and expressions of emotion, but the meaning intended by the source is not always the same as the meaning interpreted by the receiver. Messages come in many different forms and vary in characteristics such as length, formality, clarity, specificity, accuracy, comprehensiveness, valence (positive/negative), fairness (one-sided/two-sided), and a whole host of other variables.

Channel

Messages are delivered to receivers by sources through some mode such as face-to-face, print, radio, telegram, public speech, television, or film. A channel is the mode, means or media that transmits a message. With advances in technology, cell phones act as many different channels simultaneously. Consider that smartphones allow us to talk and text. Also, we can receive communication through Tik Tok, Facebook, Twitter, Email, Instagram, Snapchat, Reddit, and Vox.

The selection of a channel can greatly affect how people receive the message. For instance, a professional athlete proposed marriage to his girlfriend by sending her a ring through the postal mail service and recording a proposal message. His significant other declined his proposal and refused to return the ring.15 Obviously, face-to-face would have been the better choice. In fact, a sample of college students indicated that they would communicate face-to-face if delivering a positive message, but prefer mediated channels for sharing negative news.16

Environment

The context or situation where communication occurs is referred to as the environment. We know that the way you communicate in a professional context might be different than in a personal context; you are unlikely to talk to your overbearing boss the same way as you do to your annoying little brother. In a library, you lower your voice for other library patrons whereas nightclubs and bars necessitate high volume to be heard over the din.

The environment can be comprised of other factors besides physical location. Your amount of experience talking in front of your current classmates, the aftermath of a contested election, or an occasion such as a funeral or wedding, can make a great difference in determining appropriate content, delivery, and demeanor.

Feedback

Feedback is the response to the message. Feedback is important because the source needs to know if the receiver gets the message and how they react to it. Receivers may nod in acknowledgement of, or even agreement with, a message. Feedback can be positive like an enthused “thank you” in response to a compliment, negative such as shaking a fist at a driver who just cut you off, or ambiguous as when you get a reaction of “hmmm” or “interesting.”

Feedback can be critical as it allows sources to appropriately adapt their content or delivery in real time or over time. A communicator constantly deprived of feedback would be at the same disadvantage as a blindfolded free throw shooter who never finds out which of their techniques are most often putting the ball in the basket.

Noise

Anything that interferes with, hinders, or distorts a message is called noise. Noise keeps the message from being completely received and/or understood. A public speaking professor enjoyed accurately predicting early each semester that at least one of his student speakers would be drowned out by the appearance of “weed whacker man,” who would walk alongside the outside windows of the room creating an infernal racket. Less predictable would be when the class found it impossible to refrain from searching for the source of sirens on the surrounding streets.

In addition to actual sounds is psychological noise (e.g., thinking about last night’s terrific party or wishing for the end of class). Semantic noise involves jargon (a small business’ “core competencies” and “sweat equity”), accents (a New Yawkuh’s pronunciations heard by listeners in the Midwest), or language use (“the party was lit”). The fourth and last type of noise is physiological. If an audience member is very hungry or suffering from abdominal distress, then they might pay less attention to receiving and interpreting messages.

Additional Concept

Gatekeeper

Though it does not regularly appear in collections of communication elements, the gatekeeper is a valuable addition to any list. We sometimes enlist a “middleman” who passes along a message somewhere between the source and the receiver. Middle schoolers too bashful to address their romantivcncrush may seek a common friend to indicate their interest. Organizations are commonly hierarchical so that messages must pass through people or units that separate original sources and final destinations.

The Gatekeeper is a mythical entity that decides on whether a traveler is granted passage across a bridge or through entrances into a restricted territory. You might also think of “bosses” in video games or the terrifying character, Zuul, in the original Ghostbusters film.

An important implication of the use of gatekeepers is that, though they provide convenience and extra access to receivers, with every extra stop in a message’s route, opportunities for inaccuracies and omissions are magnified. The more people involved, the less likely that the message will escape some form of distortion. For evidence of the communicative danger, all you need to do is visit a child’s birthday party and initiate a game of Telephone!

Exercises

- Think of a communicative task like breaking up with a romantic partner and take turns constructing messages to accomplish it, each for a different channel.

- Name as many different channels as you can in sixty seconds…Go!

Models of Communication

A model is a simplified representation (often graphic) of a system that highlights the crucial components and connections of concepts, which are used to help people understand an aspect of the real-world. Models of communication help us understand how the elements of communication interact and contribute to particular outcomes. They also help to highlight the source of many communication breakdowns.

There are three different types or categories of models that communication scholars have proposed to help us understand interpersonal communication episodes: action, interaction, and transaction.

Action Models

The first type of model we’ll be exploring isaction models, a category of communication models that view communication as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver. In action models, the role of the receiver in creating meaning is minimized.

Aristotelian Model

The study of communication hearkens back to the classical era of ancient Greek civilization which began around 500 BCE and started to give way to Roman dominance around 150 BCE. The city state of Athens was home to the great philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Athens was an early democracy in that it allowed its citizens the right to vote. Their responsibility to be well-informed was assisted by the great Greek tradition of influence by way of the public speech.

Aristotle was a keen student of the craft of public speaking and is considered by many to be the father of communication studies. He wrote a treatise on persuasion known as the Rhetoric that set the course for subsequent thinking about rhetorical studies, the examination of all things public speaking. Though not particularly graphic, and with no emphasis on interpersonal communication, a representation of Aristotle’s view of communication is very much an action model:

Speaker –> Message –> Audience [in a public setting]

This depiction presents a view of communication as a one-way transmission of information that is delivered to an audience whose only job is to receive the message. Members of an audience are not treated as individuals nor are they given credit for interpreting the message. All are affected in the same way by the message and the effects are totally attributable to the speaker.

Lasswell Model

Harold Lasswell, a professor of law at Yale University with a background in political science and communication theory, published an essay in 1948 that presented his model of communication.17 Like Aristotle’s, it was more verbal than visual. Unlike Aristotle’s, it was presented in the form of what became a very famous question:

WHO

SAYS WHAT

IN WHICH CHANNEL

TO WHOM

WITH WHAT EFFECT?

Laswell’s model is articulated in a style very familiar to the pre-existing training of print journalists that taught them to include the Five Ws and an H (who, what, when, where, why, and how) early in their news stories. But he uses similar words to stand in for important elements of communication (sources, messages, channels, receivers).

Critically, in his writing about the model, Lasswell emphasized the interdependence of the elements. For instance, if the whom is an audience of millions of Super Bowl fans across the country, the channel better be a mass media selection like television or radio. Also, that makes every one of the prior elements potentially crucial in determining the outcome or effect. If the channel for the Super Bowl was only face-to-face, the vast majority of fans unable to get to the game would be left out and disappointed. After all, there’s a reason it’s called a broadcast!

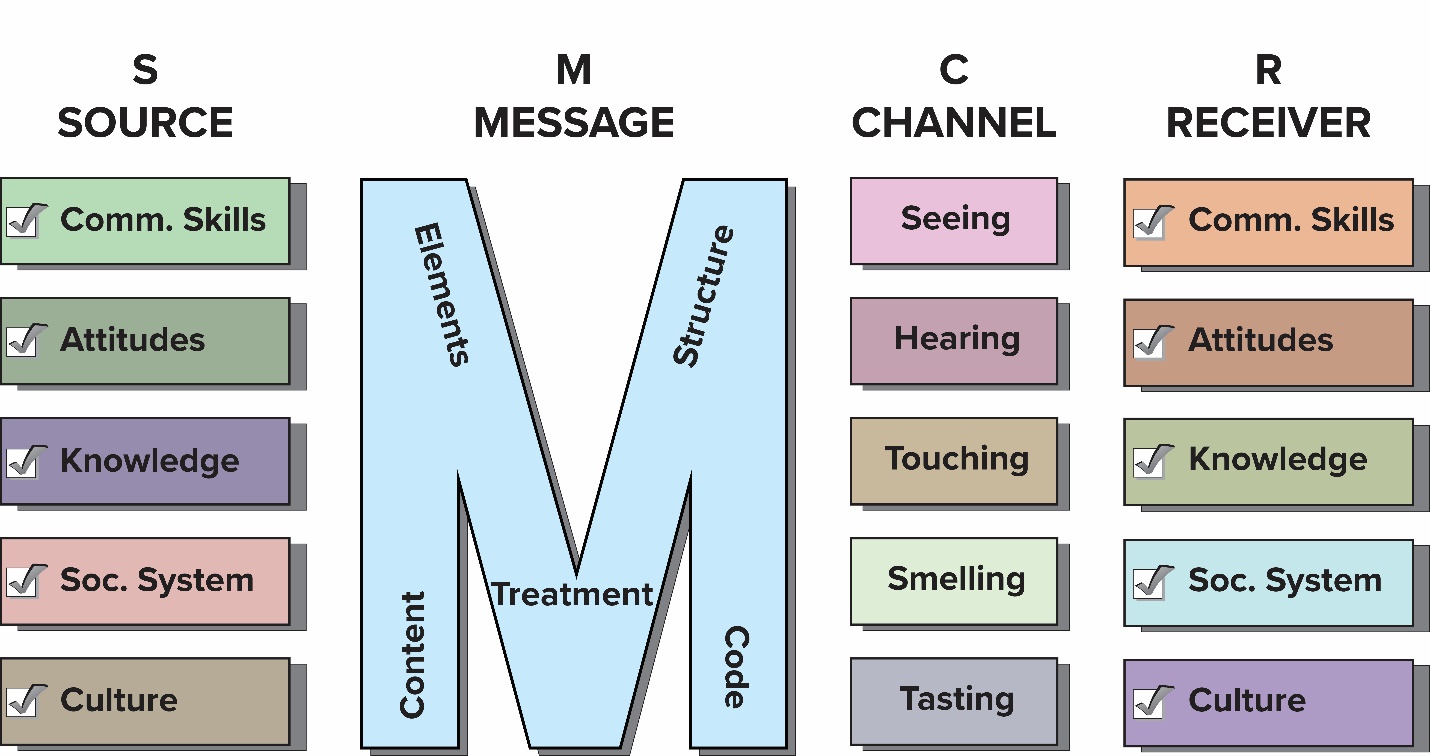

Berlo’s SMCR Model

Berlo created the SMCR model of communication in 1960.9 SMCR stands for source, message, channel, receiver. Berlo identified variables about each of the four elements, as the elements vary for every individual instance of communication (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. SMCR Model

Let’s start in the middle of the SMCR. As compared to all the other messages in all the other interactions that have ever existed, a single message will have its own elements, structure, treatment, content, and code. It may have claims and quotations for evidence, be tightly intertwined, straightforward, and presented in English. Another message could be in Spanish, contain popular slogans as well as sarcasm, and deliver both sides of a controversy somewhat randomly.

Channels also vary between different interactions. While most conceptions of channel focus on the mode of message delivery (e.g., radio, blog post, carrier pigeon), Berlo chose to think of channel as the sense (i.e., sight, sound, touch, smell, taste) employed to receive the message. It is pretty obvious which channel or sense is at work for a radio broadcast as opposed to by a sign language interpreter.

The source or sender in any given interaction has their own set of communication skills (e.g., strong at arguing, weak at listening). attitude (e.g., conservative, religious), knowledge (e.g., communication studies major, bird watching enthusiast), social system (e.g., organizations, families), and culture (e.g., western European, Afghan). These variables assume different values for one sender as opposed to another.

Receivers also come into play wielding their own set of variable values. They, too, have communication skills, culture, etc.

Critically, while receivers are not posed as actively shaping the interpretation of messages, their characteristics may affect choices the source makes. Especially when sources detect differences between themselves and their receivers, they may smartly make appropriate adjustments to their message and/or channel. For instance, if a lecturer as source wishes to teach about the use of Boolean expressions (conditional if/then assignments) in computer programming languages, they would be advised to ascertain the level of relevant knowledge their receivers possess. If they are nursing students rather than computer science majors, the message might be augmented with general context and definitions of terminology. It might also best be presented with visual aids in addition to spoken lecture. If the audience is likely to be math-phobic, a preface of cheerleading inspiration could be included within the larger message.

Berlo’s is thus the first of our models to incorporate the revered principle of sources adapting and tailoring of messages to match their audiences. Nonetheless, it is still an action model that treats communication as a one-way transmission of information.

Interaction Models

Interaction models portray both the sender AND the receiver as responsible for the effectiveness of the communication they share. One of the biggest differences between the action and interaction models is a heightened focus on feedback, the transfer of information back to sources from receivers.

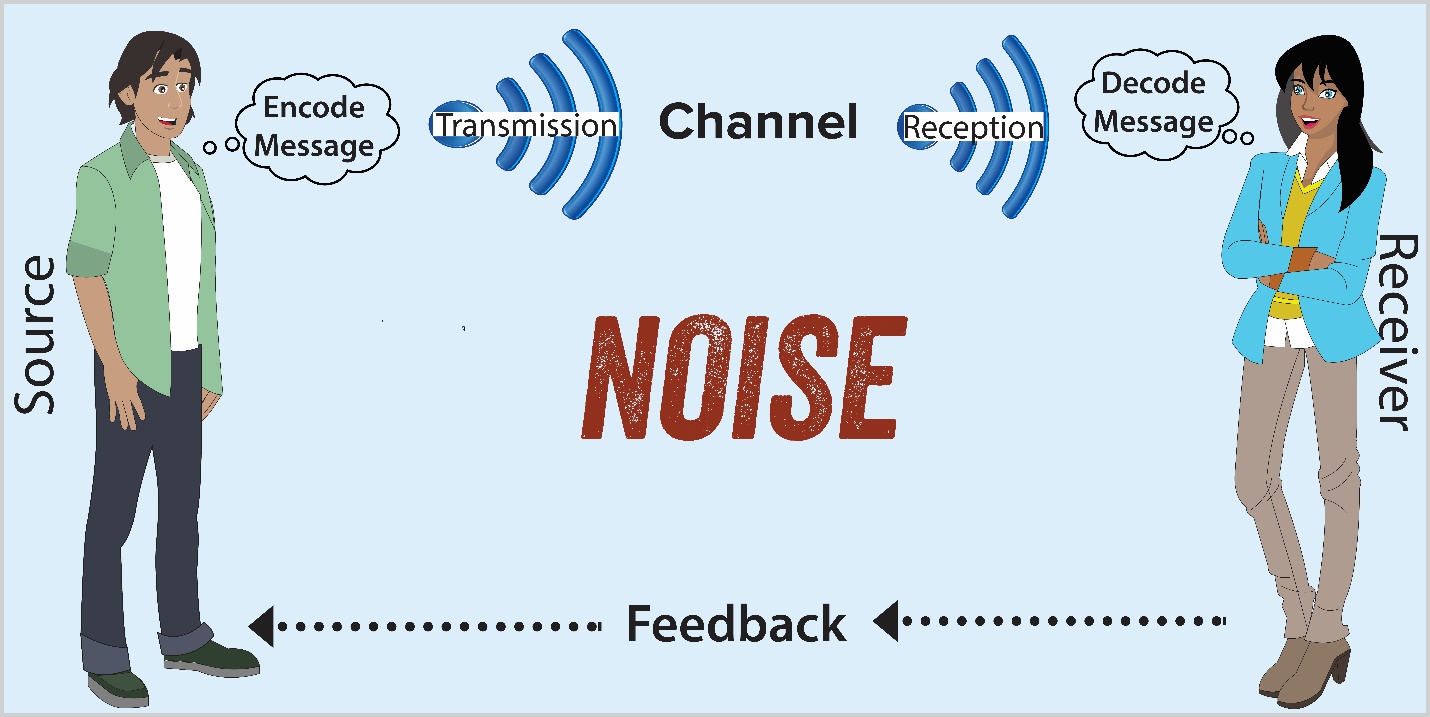

Shannon-Weaver Model

Shannon and Weaver were engineers for Bell Telephone Labs. Their job was to embody communication from a technical perspective. Telephone cables, radio waves, and television signals were technological coins of the realm in their 1960s era of electronic broadcasting and transmission. Their Shannon-Weaver model18 privileges technologies with the inclusion of encoding during transmission and decoding within reception of messages (see Figure 5). Encoding and decoding are employed to enable the actual transfer of the information.

Figure 5. Shannon-Weaver Model

The salesperson at your local American Eagle store wants to let you know that your special order from their Columbus store has arrived and you can now pick it up. They speak words into their Android phone and they are encoded into radio waves to travel through the air as channel to a cell tower and to your iPhone, which decodes the signal into sound waves for your hearing. Along the way, noise is anything that interrupts or distorts the transmission, such as you driving out of the cell tower’s range. Feedback is information that travels back to the source from the receiver. You speak into your iPhone to acknowledge the request to show up at the shop.

Shannon-Weaver qualifies as an interactional type model as the receiver is playing a bigger role than in action models and the information flows both ways.

Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson Model

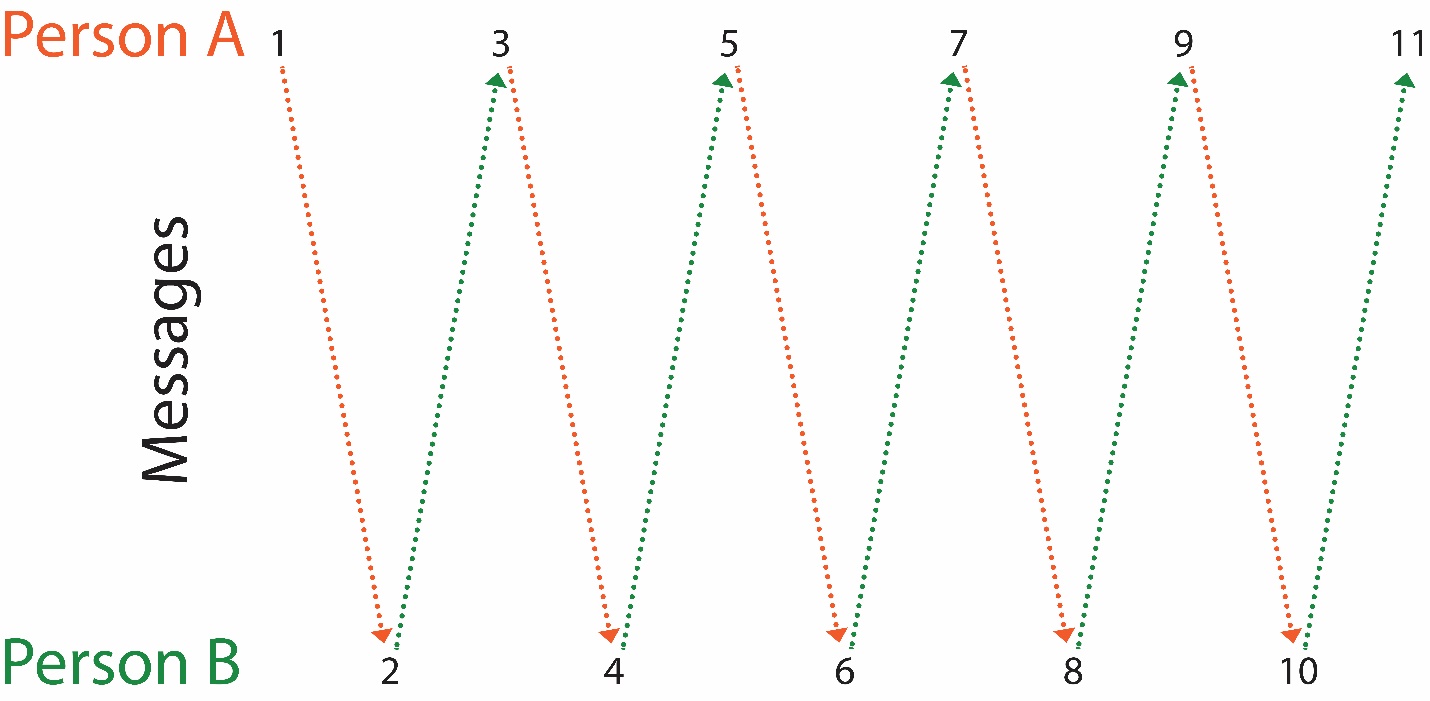

Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson emphasize the two-way nature of communication and the presence of feedback by visualizing it as a continuous process of sending and responding.19 In their model, the interactants, Person A and Person B, take turns sending and receiving (see Figure 6), much like a pair of skilled tennis players, until someone stops the volley.

Watzlawick and colleagues provide axioms, or self-evident principles, to accompany their model:

- One cannot not communicate. Even if people do not talk to each other, that still communicates a desire not to.

- Every message has content and relationship dimensions. Content is the informational subject of discussion. The relationship dimension refers to how the two communicators feel about each other.

- Communication is either symmetrical or complementary, in terms of power status, which is either equal or not. Public relations scholars suggest that organizations (ExxonMobil, Meta) share channels of communication with their target publics (drivers, Facebook users) for more symmetrical and satisfying relationships.

During his live concerts, superstar songwriter Ed Sheeran gets his audiences involved in the show. During the song, “Sing,” he asks the audience whether they are having a good time and they cheer their approval. He asks if they want to sing and they scream, “Yes!” He plays with call and response by feeding lyrics and vocal sounds like “Oh ah oh ah oh ah oh” for them to repeat. Then he encourages singing, even if they have to make up the words, without him as he holds out the microphone to the crowd. The relational dimension is probably greater than the content dimension in this joyous back-and-forth give-and-take between performer and audience.

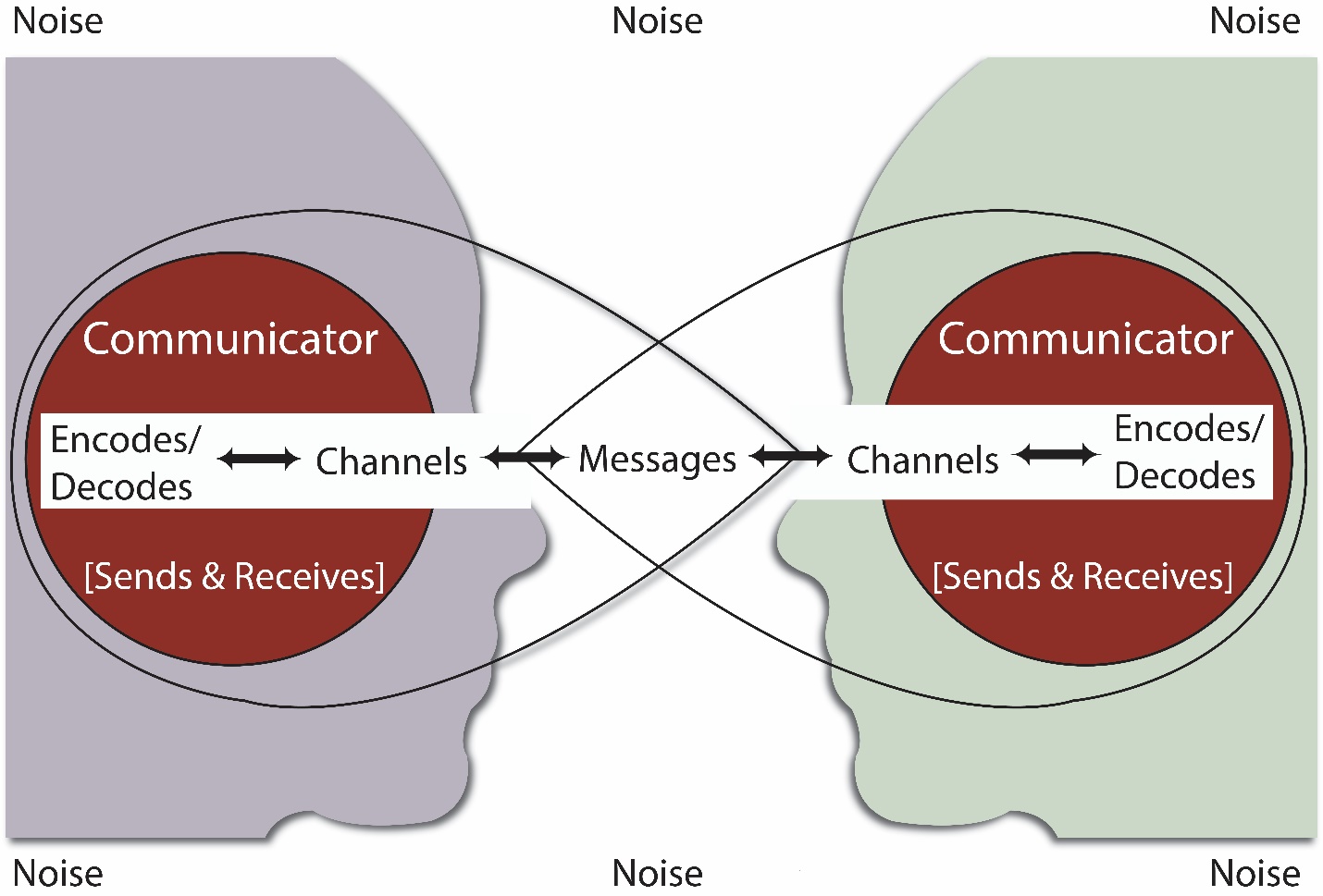

Transaction Models

Transaction models of communication differ from action and interaction ones by demonstrating how individuals often act as both senders and receivers at the same time. When parties are sending and receiving messages simultaneously, it is impossible to value only sources’ contributions to outcomes at the expense of receivers.

Barnlund’s Transactional Model

In 1970, Dean C. Barnlund created the transactional model of communication to counteract more linear action and interaction models.20 He believed that during interpersonal interactions, we are both sending and receiving messages simultaneously. This is facilitated by a multi-layered feedback system that includes verbal and nonverbal responses to messages. As with other models we have examined, the possible occurence and presence of noise in many forms poses a threat to the effective and satisfying exchange (see Figure 7).

Sydney’s mother surprises her by appearing at school when Sydney did not know that she was on leave. Sydney has been worrying because her Mom, a Naval officer, was sailing off the coast of a country that has strained relations with the United States. After the shock and relief of the initial reunion, they engage in prolonged and animated conversation. They are so excited to share news about promotions, graduations, dating, and upcoming embarkments that Sydney and her mother are talking and listening at the same time, while still managing to interrupt each other. This encounter is marked by transaction, exchange, and interpretation of meanings.

Barnlund’s transactional model, besides emphasizing the concurrent nature of interpersonal communication, also highlights its complexity and its continuous, dynamic, and ever-changing nature.

Additional Concept

Stephen Axley, a business consultant and professor of Management at Western Illinois University, developed a metaphoric version of a communication model to represent an important finding about organizational communication. He was alarmed, during his visits to many profit-making companies, to discover that almost everyone from executives to front-line workers were underestimating the importance of communication in the workplace.

Axley employed the metaphor of a conduit to illustrate this common misconception.21 A conduit is anything that something else passes through, like a plumbing pipe or an electrical wire. A perfect conduit transfers everything that runs through it so that there is no loss of material or energy along the way. Axley warns that too many organizational members think of communication as a perfect conduit. They expect that as long as they put their message out there, it will be understood, conveyed perfectly and fully.

In reality, organizational messages too often are distorted by motivation, attention, and memory deficits. Sources who take communication for granted don’t think about ideal delivery modes and adapting to their various audiences. The potential presence of gatekeepers can spin meanings in unintended directions or leave out important information.

So, the company that does not put effort into ensuring successful communication, as though they were easily engaging a perfect conduit, is doomed to unwelcome and unanticipated breakdowns. The final irony is that when things do go wrong, many organizational leaders do not think to suspect their communication practices as possibly responsible.

Key Takeaways

- Models of communication illuminate how elements of communication interact and contribute to outcomes.

- Models may reveal the reasons for communication breakdowns.

- Action models represent communication as though it was just one-way transmission of messages.

- Interaction models allow receivers a more active role in the creation of meaning but, are still mostly linear.

- Transaction models recognize that we often serve as senders and receivers, negating the binary distictions of other model types.

Exercises

- Select three short interactions from your favorite sitcom and determine the identity of each of the elements from the Lasswell model of communication.

- After revisiting Berlo’s SMCR model, identify two ways that a source and their receiver may differ and two appropriate adjustments you would then advise the sender to make to the message and/or channel.

Types of Communication

Interpersonal Communication

Interpersonal communication, which is what this book is all about, focuses on the exchange of messages between a few people. It is the process by which messages representing information, meaning, and emotion are sent and received between two or more people.

Our days are full of interpersonal communication. We wake up and say good morning to our roommates, meet our best friends for coffee to discuss our landscaper issues, work with colleagues on projects, shoot off emails to our babysitters, drop by our doctors’ offices to dispute bills with office managers, and listen to our kids’ homework complaints in the car after the school pickup.

Some scholars limit interpersonal communication to dyadic interaction, while others collapse small group communication under the interpersonal heading. Either way, these interactions take place through verbal, nonverbal, and mediated communication. We speak, gesture, write and engage in interpersonal communication with other methods as well.

Small Group Communication

Although scholars may differ on the exact number of people that make a group, we can say that a group is at least three people interacting towards a common goal. Sometimes these groups can be as large as a dozen or so, but larger groups become much harder to manage. One of the hallmarks of a small group is the ability for all the group members to engage in interpersonal interactions with all the other group members. Small group communication is any interaction that involves at least three people interacting towards a common goal.

Group goals usually follow the purpose that the group was formed for in the first place. Many gather to investigate an issue, solve a particular problem, or make or endorse a decision. Congress forms committees to fact find on issues like steroid use or gambling in sports, a few members of a marketing team strive to adjust a campaign per a client’s requests, and a campus faculty senate subcommittee may work to present a plan for addressing parking complaints to their Chancellor. Students may form groups to enhance their individual studying efforts as congregations break off into bible study groups. Groups of people struggling with their conditions, such as fear of flying or breast cancer, may be led by a psychologist in group therapy sessions. The corporate world often assembles focus groups to evaluate things like a food brand’s new product line or a movie studio’s shocking film ending.

Small group classes often study things like the origins and qualities of group leaders, the roles that people adopt in group settings, how group decisions are reached, and what portions of group talk are devoted to task or relational dimensions.

Public Communication

The next category of communication is called public communication. Public communication occurs when an individual addresses an entire audience in a public setting. This one-to-many mode of communicating differs in audience size from interpersonal (much bigger) and mass (much smaller) communication. Public communication also does not usually involve a media for transmission, other than perhaps a microphone or public address (PA) system.

Public speakers often wish to inform or persuade their audiences or mark some special occasion or ceremony with them. A superstar real estate agent might fill an auditorium at the National Association of Realtors annual convention with a workshop on increasing profits. A gubernatorial candidate appears in front of a town hall of concerned citizens to convince them how to vote. Your coach delivers an impassioned locker room speech after a lousy first half and your first-grade BFF grows up to deliver the toast at your wedding reception.

The discipline of rhetorical study, beginning with Aristotle of ancient Athens, is devoted to the analysis, appreciation, and practice, of public communication. Rhetorical scholars examine the rhetoric of CEOs, presidents, social activists and others to determine what strategies and messages they employ, how useful those are, and how future speakers can improve.

Mass Communication

Mass Communication is the process by which sources use mediated channels to address large, diverse audiences whose members are usually anonymous, dispersed in space and possibly, time. Mass media include channels such as television, radio, film, newspapers, and magazines, Sources may be individuals like United States President Ronald Reagan from his Resolute desk in the Oval Office, or collective such as the cast and production crew of the situation comedy, The Office.

As audiences may be located in ranges as wide as towns, provinces, countries or continents, mass media are utilized to broadcast across these spaces. If you think about the 2002 issue of Glamour magazine you read in your dentist’s waiting room when your phone battery died, you will realize that mass media allows for a sort of time travel between source and receiver, as well.

Communication technologies have complicated our understanding of mass media as the Internet or podcasts may be consumed individually or en masse. Also, the 1980s and 1990s increase in bandwidth from cable providers allowed for “narrowcasting” on networks that catered only to enthusiasts of golf, cooking, shopping, or true crime. This phenomenon developed further specificity with the digital advances that enabled social media.

Mass media outlets like television provide great benefits like information, entertainment, and companionship. However, research has investigated the potential drawbacks, too. In the 1930s, the Payne Fund series of studies found movie theatres to be sites where impressionable audiences, especially young ones, were influenced powerfully and uniformly to believe or do things that social norms otherwise discouraged.22 Research since then has sometimes concluded in the opposite direction, showing that consumers of media tend to choose and use media according to their own needs and desires, rather than be overpowered by it..23

Computer Mediated Communication

Another type of communication is computer mediated communication, or the use of some form of digital technology to facilitate interaction between two or more people. We are surrounded by different digital media options and social media platforms such as Facebook/Meta, YouTube, Twitter/X, Instagram, WhatsApp, and TikTok, and new ones keep evolving to replace others like MySpace, Friendster, Vine, and YikYak.

The Interpersonal Communication in Mediated Contexts chapter provides an extensive treatment of its history, features, and relevant theories.

Organizational Communication

An organization is a social, structured collectivity in which activities are coordinated in order to achieve individual and collective goals. The University of Southern California, the Environmental Protection Agency, Apple Inc., the Episcopalian Church, the American Heart Association, and your local Walmart are all organizations. Companies, corporations, businesses, agencies, and nonprofits are the sites of organizational communication, the interaction between members of an organization.

As organizations are often big places where their members or employees are earning a living or working towards common initiatives, the nature of communication in them tends to be different than in everyday interpersonal interactions. Your buddies may complain about how bosses at their part time jobs treat, and talk to, them differently than anyone else in their lives.

Organizational communication tends to be more formalized and regulated. New members have to be assimilated into the organizational culture by learning about its rules, expectations, norms, and even, language idiosyncrasies. Annahstasia delivered pizza for Domino’s in the 1990s to eke her way through graduate school, so she had to learn about terms like “cashing out” and “prepping boxes,” expectations about how to drive safely while trying to beat the ill-fated 30-minute delivery guarantee, norms about rushing in the store instead of out of it, and rules about speaking to customers differently than coworkers.

Organizational members must acquire knowledge about hierarchies and divisions as well as how information is expected to be shared among them. Organizational communication scholars are interested in aspects such as bureaucracy, standardization, interdependence, sensemaking, narrative, rituals, gender issues, power and ideology. The Relationships at Work provides deeper coverage of organizational communication.

Public Affairs and Issue Management

While organizational members engage in organizational communication, organizations as collectives interact with their publics. Exxon spokespersons had to explain how their Valdez oil spill happened in 1989 and what the company would do to make up for it and prevent future disasters. Many companies promote their devotion to equal rights during the annual Pride week in the United States or participate in charity causes like the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge.

Organizations communicate to a variety of publics. They promote their corporate social responsibility to the general public in marketing campaigns, lobby politicians to enact regulations that will benefit their bottom line, issue press releases to affect positive coverage from the media, and gather stockholders to maintain enthusiasm about a brand’s prospects.

Public relations professionals and corporate representatives who handle risk and crisis communication are examples of the practice of public affairs and issue management.

Context-Situated Communication

The discipline of communication studies recognizes forms of communication that may involve interpersonal, mass, public, or organizational communication but that take place in specific and well-established areas or contexts. We are referring to these as instances of context-situated communication.

Political communication examines congressional persuasion, campaign materials, officials’ websites, and election debates. Intercultural communication takes place between parties who represent different cultures such as different nations, regions, religions, or economic classes.

Health communication has expanded from its initial predominant focus on communicative challenges between patients and their health care providers to scrutiny of media coverage of medical issues, government and agency health campaigns waged to change behavior, materials promoting alternative medicine, and caregiving and social support for people with illness, injury, or disability.

Sport communication involves verbal and nonverbal communication between teammates, biases in sport broadcasting, game reporting and announcing, franchise management, meaning of team nicknames, coaching relationships, and sport fan cultures.

Gender communication searches for differences, but also similarities, in how people of different gender identities relate and communicate. Trends in how people pursue romance, employ conversation, use and abuse others, interact at work, and get socialized in school, are examined. Sometimes pursued from a feminist perspective that seeks to promote true equality among all people, gender communication may also inspire interest in sexual, racial and ethnic, and religious identities as well.

Exercises

- Discuss the ways that advertising in mass media outlets can both help and hurt consumers.

- Describe an interaction you had with a coworker that would have seemed odd outside of the workplace, and why.

- What is your favorite famous public speech by a politician or social activist? What made it so great?

Communication Ethics

If we are going to pursue a better life through enhanced communication, we should certainly consider and practice a code of communication ethics. It is important to be mindful of what you say to others. You do not want people to think you are deceptive or that you are untrustworthy. Trust can take a long time to establish but it can vanish in an instant.

It is essential that every time you communicate, you consider the consequences of your messages and whether you are treating others fairly and with the same respect that you desire and deserve. The Golden Rule dictates that we treat others as we would have them treat us and communication is a perfect proving ground for this moral code.

It may not be instantaneously obvious what it means to practice interpersonal communication ethically. Fortunately, the National Communication Association has created a general credo for ethical communication.24 The subheadings below represent the nine statements created by the National Communication Association to help guide conversations related to communication ethics.

1. Honesty and Integrity

We advocate truthfulness, accuracy, honesty, and reason as essential to the integrity of communication.

We live in a world where the division of fact and fiction, real-life and fantasy, truth and lies, real news and fake news, etc. has become increasingly blurry. The NCA credo argues that ethical communication should always strive towards truth and integrity. As such, it’s important to consider our interpersonal communication and ensure that we are not spreading lies or falsehoods.

2. Diversity and Civility

We endorse freedom of expression, diversity of perspective, and tolerance of dissent to achieve the informed and responsible decision making fundamental to a civil society.

It is perfectly appropriate to disagree with people as long as we do so in a civilized manner. So much of our interpersonal communication in the 21st Century seems to be about insisting, “I’m right, and you’re wrong.” We should instead remember that it’s possible for many different vantage points to have equal value. People’s experiences in life lead them to different positions that can be equally valid. From an ethical perspective, it’s very important to listen to others and not immediately start thinking about our comebacks or counter-arguments. Otherwise, we’re not listening openly and fairly.

3. Respecting and Responding

We strive to understand and respect other communicators before evaluating and responding to their messages.

It is critical that we approach our interpersonal interactions with understanding and respect. It can be tough to listen to messages that you strongly disagree with, but we can still give opposing viewpoints a hearing and respond in ways that signal respect for each other.

4. Access and Well-Being

We promote access to communication resources and opportunities as necessary to fulfill human potential and contribute to the well‐being of individuals, families, communities, and society.

As communication scholars and students, we believe that everyone should have the opportunity to perform and improve their communication. One of the reasons we’ve written this book is because we believe that all students should have access to an interpersonal communication textbook that is either very affordable or free. Furthermore, we believe that everyone should have the opportunity to develop their interpersonal communication skills, listening skills, presentation skills, and social skills. Ultimately, developing communication skills helps people in their interpersonal relationships and makes them better equipped to serve the welfare of themselves and others.

5. Communication Climates

We promote communication climates of caring and mutual understanding that respect the unique needs and characteristics of individual communicators.

As communicators, we need to take a two-pronged approach to our interpersonal interactions. First, we need to care about the needs of others. We need to understand that our communication can either build people up or tear them down. This doesn’t mean there are never occasions where you should tell people that they’re wrong, but there are ways of doing this that correct without reducing their self-esteem.

Second, we need to strive for mutual understanding. We should aspire to ensure that our messages are interpreted correctly by others and that we’re interpreting others’ messages correctly as well. We should avoid jumping to conclusions and assuming that someone else has anything other than goodwill towards us, at least until their actions indicate otherwise..

6. Condemning Degradation

We condemn communication that degrades individuals and humanity through distortion, intimidation, coercion, and violence, and through the expression of intolerance and hatred.

We believe that any communication that degrades another person is reprehensible. It is easy enough to label obvious hate messages as disgusting (e.g., anti-immigrant signs, burning crosses, racist graffiti, etc.). However, many people engage in biased language without realizing it’s happening. We’ll discuss the issue of biased language and how to avoid it in more detail in the Verbal Communication chapter. It is not enough to refrain from engaging in hurtful discourse. We have to also speak out against others who do.

7. Courage of Conviction

We are committed to the courageous expression of personal convictions in pursuit of fairness and justice.

We live in a world where injustices are still very prevalent. From outsized anti-immigrant rhetoric to laws regarding medical treatment for transgender people, we believe that it’s important to pursue fairness and justice. Whether it’s remembering to call someone by their preferred names or supporting individuals seeking equal rights and protection under the law, we should be on the side of progressive justice and civil rights for all.

8. Information Sharing and Privacy

We advocate sharing information, opinions, and feelings when facing significant choices while also respecting privacy and confidentiality.

It was not so long ago that we emerged from the isolated throes of a worldwide pandemic. It is indisputable that some made poor choices with regard to the well-being of themselves and others. We must be effortful in our attempts to fill information gaps and correct disinformation, particularly when it has consequences for the community. Still, a balance must be achieved so that disclosures, even of immoral or uninformed positions, are not publicized if they were shared in confidence.

9. Responsibility for Consequences

We accept responsibility for the short‐ and long‐term consequences for our own communication and expect the same of others.

Lastly, the National Communication Association’s Credo for Ethical Communication advocates that people take responsibility for the consequences of their communication. If you say something that unduly hurts someone else’s feelings, it’s important to recognize that and apologize. If we accidentally spread false information, it’s important to correct the facts when we learn them. We should also not promote language or causes that operate at the expense of other peoples’ positive conditions.

Rodrick Hart and Don Burks coined the term “rhetorical sensitivity” to help explain awareness of our own communicative behaviors. According to Hart and Burks,

The rhetorically sensitive person (a) tries to accept role‐taking as part of the human condition, (b) attempts to avoid stylized verbal behavior, (c) is characteristically willing to undergo the strain of adaptation, (d) seeks to distinguish between all information and that information acceptable for communication, and (e) tries to understand that an idea can be rendered in multi‐form ways.25

With these nine principles in mind, we can execute exemplary communication while knowing that it is doing far more good than harm. It is hard to ask for more (or less) than that!

Key Takeaways

- Honesty, respect, and acceptance of other’s positions as valid, even if not correct, is vital.

- Everyone deserves access to channels of communication, a climate of understanding, and desired levels of privacy.

- We must not practice, nor bystand others’ acts or messages of degradation or hate.

- Acting for justice is critical, as is recognizing how our communication can hurt or impede others.

Exercises

- Revisit the nine statements of ethics from the National Communication Association.

- Vow to put them into practice to the best of your ability.

Key Terms

action models

A category of communication models that view communication as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver.

appropriate communication

Communication featuring tactics and behaviors that most people would consider acceptable and ethical.

channel

The mode, means or media that transmits a message.

cognitive complexity

A characteristic of seeing the world from multiple and nuanced perspectives that is associated with communication effectiveness.

communication

The process by which messages representing information, meaning, and emotion are sent and received between two or more people.

communication competence

Communication that is both appropriate and effective.

communication ethics

Considering the consequences of your messages and whether you are treating others fairly and with the same respect that you deserve and desire.

computer mediated communication

The use of some form of digital technology to facilitate interaction between two or more people.

context-situated communication

The type of communication that may be accomplished as interpersonal, mass, public, and organizational but that takes place in specific and well-established areas or contexts, such as politics, health, sports, and gender.

culture

A group of people who through a process of learning can share perceptions of the world that influences their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.

effective communication

Communication that achieves the goal(s) at least one party had for an interaction.

emotional intelligence

The ability to recognize your own emotions and the emotions of others.

environment

The context or situation where communication occurs.

feedback

The response to the message.

gatekeeper

A “middleman” who passes along a message somewhere between the source and the receiver.

group

Three or more people interacting together to achieve a common goal.

interaction models

A category of communication models that portray both the sender AND the receiver as responsible for the effectiveness of the communication they share.

interpersonal communication

Communication between a small number of people that is the essence of relationships and often face-to-face and synchronous.

looking glass self

The concept that recognizes our self-images are shaped by how others act around, and speak to, us as well as by what we inherently know about ourselves.

mass communication

The process by which sources use mediated channels to address large, diverse audiences whose members are usually anonymous, dispersed in space and possibly, time.

message

Information, meaning, and/or emotion conveyed by verbal or nonverbal means, the content of a communication interaction.

model

A simplified representation (often graphic) of a system that highlights the crucial components and connections of concepts, which are used to help people understand an aspect of the real world.

noise

Anything that interferes with, hinders, or distorts a message.

organization

A social, structured collectivity in which activities are coordinated in order to achieve individual and collective goals

organizational communication

The interaction between members of an organization.

process

Something that is ongoing, dynamic, and changing with a purpose or towards some end.

public affairs and issue management

The communication employed as organizations as collectives interact with their publics such as citizens, consumers, government bodies, and the media.

public communication

A one-to-many mode of communicating that occurs when an individual addresses an entire audience in a public setting.

receiver

The individual who decodes the message and tries to understand the source of the message and the meaning they intended.

self-monitoring

The ability to focus on and recognize your own behavior, including communication.

sender

The person who decides to communicate, identifies the intent of the message (entertain, inform, distract), and constructs its content.

small group communication

Any interaction that involves at least three people interacting towards a common goal.

source

The person who decides to communicate, identifies the intent of the message (entertain, inform, distract), and constructs its content.

transaction models

A category of communication models that demonstrate how individuals often act as both source and receiver simultaneously.

Notes

The process by which messages representing information, meaning, and emotion are sent and received between two or more people.

Communication between a small number of people that is the essence of relationships and often face-to-face and synchronous.

The concept that recognizes our self-images are shaped by how others act around, and speak to, us as well as by what we inherently know about ourselves.

Something that is ongoing, dynamic, and changing with a purpose or towards some end

A group of people who through a process of learning can share perceptions of the world that influences their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.

Communication that is both socially appropriate and personally effective.

Communication featuring tactics and behaviors that most people would consider acceptable and ethical.

Communication that achieves the goal(s) at least one party had for an interaction.

A characteristic of seeing the world from multiple and nuanced perspectives that is associated with communication effectiveness.

The ability to recognize your own emotions and the emotions of others.

The ability to focus on and recognize your own behavior, including communication.

The person who decides to communicate, identifies the intent of the message (entertain, inform, distract), and constructs its content.

The person who decides to communicate, identifies the intent of the message (entertain, inform, distract), and constructs its content.

The individual who decodes the message and tries to understand the source of the message and the meaning they intended.

The information, meaning, and/or emotion conveyed by verbal or nonverbal means, the content of a communication interaction.

The mode, means or media that transmits a message.

The context or situation where communication occurs.

The response to the message.

Anything that interferes with, hinders, or distorts a message.

A "middleman" who passes along a message somewhere between the source and the receiver.

A simplified representation (often graphic) of a system that highlights the crucial components and connections of concepts, which are used to help people understand an aspect of the real world.

A category of communication models that view communication as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver.

A category of communication models that portray both the sender AND the receiver as responsible for the effectiveness of the communication they share.

A category of communication models that demonstrate how individuals often act as both sender and receiver simultaneously.

Three or more people interacting together to achieve a common goal.

Any interaction that involves at least three people interacting towards a common goal.

A one-to-many mode of communicating that occurs when an individual addresses an entire audience in a public setting.

The process by which sources use mediated channels to address large, diverse audiences whose members are usually anonymous, dispersed in space and possibly, time.

The use of some form of technology to facilitate information between two or more people.

A social, structured collectivity in which activities are coordinated in order to achieve individual and collective goals

The interaction between members of an organization.

The communication employed as organizations as collectives interact with their publics such as citizens, consumers, government bodies, and the media.

The type of communication that may be accomplished as interpersonal, mass, public, and organizational but that takes place in specific and well-established areas or contexts, such as politics, health, sports, and gender.

Considering the consequences of your messages and whether you are treating others fairly and with the same respect that you deserve and desire.