Culture in Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Define and understand culture in interpersonal communication.

- Comprehend the functions and characteristics of culture.

- Describe common cultural characteristics as they relate to communication.

One of the most important factors in our understanding of communication is culture. Every one of us has grown up in a unique cultural environment, and this culture has impacted how we communicate. Culture is such an ingrained part of who we are that we often don’t even recognize our own culture. In this chapter, we’re going to explore culture and its impact on interpersonal communication.

What is Culture?

When people hear the word “culture,” many different images often come to mind. Maybe you immediately think of going to the ballet, an opera, or an art museum. Other people think of traditional dress like that seen from Kashmir in Figure 1. However, the word “culture” has a wide range of different meanings to a lot of different people. For example, when you travel to a new country (or even a state within your own country), you expect to encounter different clothing, languages, foods, rituals, etc.… The word “culture” is a hotly debated term among academics. For our purposes, we are going to talk about culture as “a group of people who through a process of learning are able to share perceptions of the world which influences their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.”4 Let’s break down this definition.

First, when we talk about “culture,” we are starting off with a group of people. One of the biggest misunderstandings new people studying culture have is that an individual can have their own personalized culture. Culture is something that is formed by the groups that we grow up in and are involved with through our lifetimes.

Second, we learn about our culture. In fact, culture becomes such an ingrained part of who we are that we often do not even recognize our own culture and how our own culture affects us daily. Just like language, everyone is hardwired to learn culture. What culture we pick up is ultimately a matter of the group(s) we are born into and raised. Just like a baby born to an English-speaking family isn’t going to magically start speaking French out of nowhere, neither will a person from one culture adopt another culture accidentally.

Third, what we learn ultimately leads to a shared perception of the world. All cultures have stories that are taught to children that impact how they view the world. If you are raised by Jewish or Christian parents/guardians, you will learn the creation story in the Bible. However, this is only one of many different creation myths that have abounded over time in different cultures:

- The Akamba in Kenya say that the first two people were lowered to earth by God on a cloud.

- In ancient Babylon and Sumeria, the gods slaughtered another god named We-ila, and out of his blood and clay, they formed humans.

- One myth among the Tibetan people is that they owe their existence to the union of an ogress, not of this world, and a monkey on Gangpo Ri Mountain at Tsetang.

- And the Aboriginal tribes in Australia believe that humans are just the decedents of gods.5

Ultimately, which creation story we grew up with was a matter of the culture in which we were raised. These different myths lead to very different views of the individual’s relationship with both the world and with their God, gods, or goddesses.

Fourth, the culture we are raised in will teach us our beliefs, values, norms, and rules.

- Beliefs are assumptions and convictions held by an individual, group, or culture about the truth or existence of something. For example, in all of the creation myths discussed in the previous paragraph, these are beliefs that were held by many people at various times in human history.

- Next, we have values, or important and lasting principles or standards held by a culture about desirable and appropriate courses of action or outcomes. This definition is a bit complex, so let’s break it down.

- When looking at this definition, it’s important first to highlight that different cultures have different perceptions related to both courses of action or outcomes. For example, in many cultures throughout history, martyrdom (dying for one’s cause) has been something deeply valued. As such, in those cultures, putting one’s self in harm’s way (course of action) or dying (outcome) would be seen as both desirable and appropriate. Within a given culture, there are generally guiding principles and standards that help determine what is desirable and appropriate. In fact, many religious texts describe martyrdom as a holy calling. So, within these cultures, martyrdom is something that is valued.

- Next, within the definition of culture are the concepts of norms and rules. Norms are informal guidelines about what is acceptable or proper social behavior within a specific culture. Rules, on the other hand, are the explicit guidelines (generally written down) that govern acceptable or proper social behavior within a specific culture. With rules, we have clearly concrete and explicitly communicated ways of behaving, whereas norms are generally not concrete, nor are they explicitly communicated. We generally do not know a norm exists within a given culture unless we violate the norm or watch someone else violating the norm.

The final part of the definition of culture, and probably the most important for our purposes, looking at interpersonal communication, is that these beliefs, values, norms, and rules will govern how people behave.

Co-cultures

In addition to a dominant culture, most societies have various co-cultures—regional, economic, social, religious, ethnic, and other cultural groups that exert influence in society. Other co-cultures develop among people who share specific beliefs, ideologies, or life experiences. For example, within the United States we commonly refer to a wide variety of different cultures: Amish culture, African American culture, Buddhist Culture, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersexed, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) culture. With all of these different cultural groups, we must realize that just because individuals belong to a cultural group, that does not mean that they are all identical. For example, African Americans in New York City are culturally distinct from those living in Birmingham, Alabama, because they also belong to different geographical co-cultures. Within the LGBTQIA culture, the members who make up the different letters can have a wide range of differing cultural experiences within the larger co-culture itself. As such, we must always be careful to avoid generalizing about individuals because of the co-cultures they belong to.

Co-cultures bring their unique sense of history and purpose within a larger culture. Co-cultures will also have their holidays and traditions. For example, one popular co-cultural holiday celebrated in the United States is Cinco de Mayo. One big mistake many U.S. citizens make is assuming Cinco de Mayo is Mexican Independence Day, which it is not. Instead, El Grito de la Indepedencia (The Cry of Independence) is held annually on September 16 in honor of Mexican Independence from Spain in 1810. Sadly, Cinco de Mayo has become more of an American holiday than it is a Mexican one. Just as an FYI, Cinco de Mayo is the date (May 5, 1862) observed to commemorate the Mexican Army’s victory over the French Empire at the Battle of Puebla that conclude the Franco-Mexican War (also referred to as the Battle of Puebla Day). We raise this example because often the larger culture coopts parts of a co-culture and tries to adapt it into the mainstream. During this process, the meaning associated with the co-culture is often twisted or forgotten.

Microcultures

The last major term we need to explain with regards to culture is what is known as a microculture. A microculture, sometimes called a local culture, refers to cultural patterns of behavior influenced by cultural beliefs, values, norms, and rules based on a specific locality or within an organization. “Members of a microculture will usually share much of what they know with everyone in the greater society but will possess a special cultural knowledge that is unique to the subgroup.”6 If you’re a college student and you’ve ever lived in a dorm, you may have experienced what we mean by a microculture. It’s not uncommon for different dorms on campus to develop their own unique cultures that are distinct from other dorms. They may have their own exclusive stories, histories, mascots, and specializations. Maybe you live in a dorm that specializes in honor’s students or pairs U.S. students with international students. Perhaps you live in a dorm that is allegedly haunted. Maybe you live in a dorm that values competition against other dorms on campus, or one that doesn’t care about the competition at all. All of these examples help individual dorms develop unique cultural identities.

We often refer to microcultures as “local cultures” because they do tend to exist among a small segment of people within a specific geographical location. There’s quite a bit of research on the topic of classrooms as microcultures. Depending on the students and the teacher, you could end up with radically different classroom environments, even if the content is the same. The importance of microcultures goes back to Abraham Maslow’s need for belonging. We all feel the need to belong, and these microcultures give us that sense of belonging on a more localized level.

For this reason, we often also examine microcultures that can exist in organizational settings. One common microculture that has been discussed and researched is the Disney microculture. Employees (oops! We mean cast members) who work for the Disney company quickly realize that there is more to working at Disney than a uniform and a name badge. Disney cast members do not wear uniforms; everyone is in costume. When a Disney cast member is interacting with the public, then they are “on stage;” when a cast member is on a break away from the public eye, then they are “backstage.” From the moment a Disney cast member is hired, they are required to take Traditions One and probably Traditions Two at Disney University, which is run by the Disney Institute (http://disneyinstitute.com/). Here is how Disney explains the purpose of Traditions: “Disney Traditions is your first day of work filled with the History & Heritage of The Walt Disney Company, and a sprinkle of pixie dust!”7 As you can tell, from the very beginning of the Disney cast member experience, Disney attempts to create a very specific microculture that is based on all things Disney.

Key Takeaways

- Over the years, there have been numerous definitions of the word culture. For our purposes, we define culture as a group of people who, through a process of learning, can share perceptions of the world, which influences their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.

- In the realm of cultural studies, we discuss three different culturally related terms. First, we have a dominant culture, or the established language, religion, behavior, values, rituals, and social customs of a specific society. Within that dominant culture will exist numerous co-cultures and microcultures. A co-culture is a regional, economic, social, religious, ethnic, or other cultural groups that exerts influence in society. Lastly, we have microcultures or cultural patterns of behavior influenced by cultural beliefs, values, norms, and rules based on a specific locality or within an organization.

The Function of Culture

Collective Self-Esteem

Henri Tajfel originally coined the term “collective self” as “that aspect of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership in a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership.”8 Jennifer Crocker and Riia Luhtanen took Tajfel’s ideas one step further and discussed them as an individual’s collective self-esteem, or the aspect of an individual’s self-worth or self-image that stems from their interaction with others and evaluation of their various social groups.9 Based on their research, Crocker and Luhtanen found four different factors related to an individual’s collective self-esteem: private collective esteem, membership esteem, public collective esteem, and importance to identity.

The first factor of collective self-esteem is the individual’s private collective esteem, or the degree to which an individual positively evaluates their group. Every individual belongs to a wide range of groups, and we can evaluate these groups as either positive or negative. Imagine you’ve been brought up in a community where gang membership is a very common practice. You may have been forced into gang life at a very early age. Over time, you may start to see a wide array of problems with gangs, so you may start to devalue the group. In this case, you would have low private collective esteem.

The second factor of collective self-esteem is membership esteem, which is the degree to which an individual sees themself as a “good” member of a group. Maybe you’ve belonged to a religious organization your entire life. Over time, you start to find yourself wondering about the organization and your place within the organization. Maybe you see yourself as having ideas and opinions that are contrary to the organization, or maybe your behavior when not attending religious services is not what the organization would advocate. In this case, you may start to see yourself as a “bad” member of this organization, so your membership esteem would be lower than someone who sees themself as a “good” member of this organization.

The third factor of collective self-esteem is public collective self-esteem, or the degree to which nonmembers of a group evaluate a group and its members either positively or negatively. Maybe you’re a lesbian college student at a very progressive institution where students overwhelmingly support LGBTQIA rights. In this case, the collective views the group that you belong to positively.

The final factor of collective self-esteem is importance to identity, or the degree to which group membership is important to an individual. As mentioned earlier, we all belong to a wide range of cultural groups. Some of these groups are near and dear to us, while others are ones we don’t think about very often, so they just aren’t very important to us. For example, if you’re someone who has always lived in Charleston, South Carolina, then being a member of the Southerner cultural group may be a very important part of your identity. If you ended up leaving the south and moving to Oregon, this “southerner” label may take on even more meaning for you and become an even stronger identity marker because your immediate cultural group no longer surrounds you.

There has been a wealth of research conducted on the importance of collective self-esteem on individuals. For example, if you compare your cultural groups as being better than other cultural groups, then you will experience more positive emotions and self-evaluations.10 However, the opposite is also true. Individuals who compare their cultural groups to those cultural groups that are perceived as “better-off,” tend to experience more negative emotions and lower self-evaluations. As you can imagine, an individual who is a member of a group that is generally looked down upon by society will have a constant battle internally as they battle these negative emotions and subsequent lower self-evaluations because of membership within a cultural group.

You may be wondering how this ultimately impacts interpersonal communication. Research has examined how an individual’s collective self-esteem impacts their interpersonal interactions.11 The researchers found that “during interactions in which multicultural persons felt that their heritage culture was being positively evaluated, they were more likely to perceive the interaction as intimate, they disclosed more and perceived their interaction partner as more disclosing, they enjoyed the interaction more, and they were more likely to indicate that they felt personally accepted.”12 Furthermore, individuals with high collective self-esteem generally had more favorable interactions with people of differing cultures. On the other hand, individuals who had low levels of public collective self-esteem tended to recall less intimate social interactions with people from different cultures. As you can see, cultural self-esteem is an essential factor in our intercultural interactions with other people. For this reason, understanding how we view our cultural identities becomes very important because it can predict the types of intercultural interactions we will ultimately have.

Stereotyping

Stereotypes are “a set of beliefs about the personal attributes of a social group.”13 Many people immediately hear the word “stereotype” and cringe because it’s often filled with negative connotations. However, not all stereotypes are necessarily wrong or bad. Some stereotypes exist because they are accurate.14 Often groups have real differences, and these differences are not bad or wrong; they just are. Let’s look at a real stereotype that plays out. When people hear the words “flight attendant,” they generally associate females with the term. In fact, in the 1980s only 19% of flight attendants were male, and today 26% of flight attendants are male.15 Are all flight attendants female? Obviously, not; however, the majority of flight attendants are female. We call these types of jobs sex-segregated because the jobs are held overwhelmingly by one biological sex or the other when there is no real reason why either sex cannot be effective within the job. However, many also hold the stereotype that flight attendants are all young. Although this was historically true, the ages of flight attendants has changed: 16-24 year olds (4.9%), 25-34 year olds (16.8%), 35-44 year olds (29.7%), 45-54 year olds (28.2%), and 55+ year olds (21.4%).

As you can see, the overwhelming majority of flight attendants are 35 years of age or older. Almost half of flight attendants today are over 45 years of age. In this case, the stereotype of the young flight attendant simply doesn’t meet up with reality.

Furthermore, there can be two distinctly different types of stereotypes that people hold: cultural and personal. Cultural stereotypes are beliefs possessed by a larger cultural group about another social group, whereas personal stereotypes are those held by an individual and do not reflect a shared belief with their cultural group(s). In the case of cultural stereotypes, cultural members share a belief (or set of beliefs) about another cultural group. For example, maybe you belong to the Yellow culture and perceive all members of the Purple culture as lazy. Often these stereotypes that we have of those other groups (e.g., Purple People) occur because we are taught them since we are very young. On the other hand, maybe you had a bad experience with a Purple Person being lazy at work and in your mind decide all Purple People must behave like that. In either case, we have a negative stereotype about a cultural group, but how we learn these stereotypes is very different.

Now, even though some stereotypes are accurate and others are inaccurate, it does not mitigate the problem that stereotypes cause. Stereotypes cause problems because people use them to categorize people in snap judgments based on only group membership. Going back to our previous example, if you run across a Purple person in your next job, you’ll immediately see that person as lazy without having any other information about that person. When we use blanket stereotypes to make a priori (before the fact) judgments about someone, we distance ourselves from making accurate, informed decisions about that person (and their cultural group). Stereotypes prejudice us to look at all members of a group as similar and to ignore the unique differences among individuals. Additionally, many stereotypes are based on ignorance about another person’s culture.

Culture as Normative

Another function of culture is that it helps us establish norms. Essentially, one’s culture is normative,16 or we assume that our culture’s rules, regulations, and norms are correct and those of other cultures are deviant, which is highly ethnocentric. The term ethnocentrism can be defined as the degree to which an individual views the world from their own culture’s perspective while evaluating other cultures according their own culture’s preconceptions, often accompanied by feelings of dislike, mistrust, or hate for cultures deemed inferior. All of us live in a world where we are raised in a dominant culture. As a result of being raised in a specific dominant culture, we tend to judge other cultures based on what we’ve been taught within our own cultures. We also tend to think our own culture is generally right, moral, ethical, legal, etc. When a culture appears to waiver from what our culture has taught is right, moral, ethical, legal, etc., we tend to judge those cultures as inferior.

Key Takeaways

- Collective self-esteem is an individual’s self-worth or self-image that stems from their interaction with others and evaluation of their various social groups. Research has shown that there are four significant parts to collective self-esteem: private collective esteem, membership esteem, public collective esteem, and importance to identity.

- Stereotypes are beliefs that we hold about a person because of their membership in a specific cultural group. Interpersonally, stereotypes become problematic because we often filter how we approach and communicate with people from different cultures because of the stereotypes we possess.

Cultural Characteristics and Communication

High and Low Context Cultures

One of the earliest researchers in the area of cultural differences and their importance to communication was a researcher by the name of Edward T. Hall. According to Hall, all cultures incorporate both verbal and nonverbal elements into communication. In his 1959 book, The Silent Language, Hall states, “culture is communication and communication is culture.”19 Previously, we talked about the importance of nonverbal communication. We also mentioned that nonverbal communication isn’t exactly universal. Some gestures can mean wildly different things in different parts of the world.

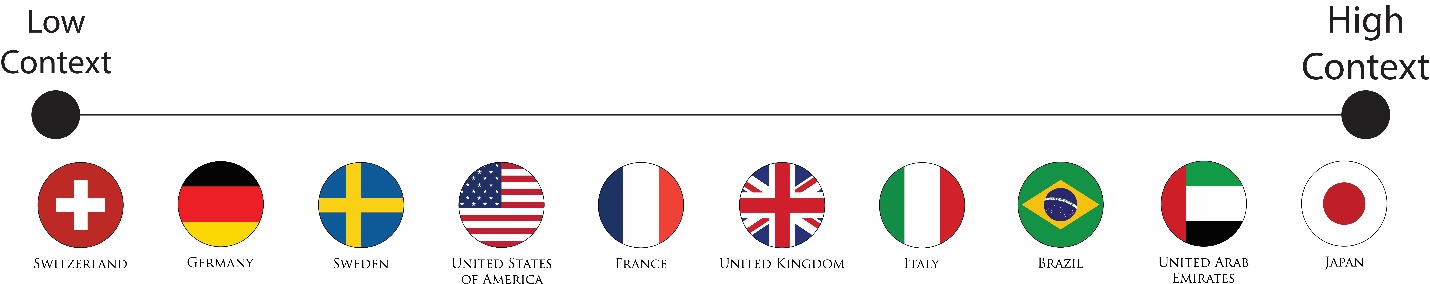

One of Halls most essential contributions to the field of intercultural communication is the idea of low-context and high-context cultures. The terms “low-context culture” (LCC) and “high-context culture” (HCC) were created by Hall to describe how communication styles differ across cultures. In essence, “in LCC, meaning is expressed through explicit verbal messages, both written and oral. In HCC, on the other hand, intention or meaning can best be conveyed through implicit contexts, including gestures, social customs, silence, nuance, or tone of voice.”20 Table 1 further explores the differences between low-context and high-context cultures. In Table 1, we broke down issues of context into three general categories: communication, cultural orientation, and business.

| Low-Context | High-Context | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | Type of Communication | Explicit Communication | Implicit Communication |

| Communication Focus | Focus on Verbal Communication | Focus on Nonverbal Communication | |

| Context of Message | Less Meaningful | Very Meaningful | |

| Politeness | Not Important | Very Important | |

| Approach to People | Direct and Confrontational | Indirect and Polite | |

| Cultural Orientation | Emotions | No Room for Emotions | Emotions Have Importance |

| Approach to Time | Monochromatic | Polychromatic | |

| Time Orientation | Present-Future | Past | |

| In/Out-Groups | Flexible and Transient Grouping Patterns | Strong Distinctions Between In and Out-Groups | |

| Identity | Based on Individual | Based on Social System | |

| Values | Independence and Freedom | Tradition and Social Rules/Norms | |

| Business | Work Style | Individualistic | Team-Oriented |

| Work Approach | Task-Oriented | Relationship-Oriented | |

| Business Approach | Competitive | Cooperative | |

| Learning | Knowledge is Transferable | Knowledge is Situational | |

| Sales Orientation | Hard Sell | Soft Sell | |

| View of Change | Change over Tradition | Tradition over Change |

Table 1 Low-Context vs. High-Context Cultures

You may be wondering, by this point, how low-context and high-context cultures differ across different countries. Figure 2 illustrates some of the patterns of context that exist in today’s world.21

Six Cultural Dimensions

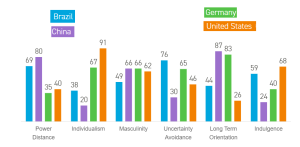

Another very important researcher in the area of culture is a man by the name of Geert Hofstede. In Geert’s research examining thousands of workers from around the globe, he has noticed a series of six cultural differences: low vs. high power distance, individualism vs. collectivism, masculinity vs. femininity, low vs. high uncertainty avoidance, long-term vs. short-term orientation, and indulgence vs. restraint. Let’s briefly look at each of these.

Low vs. High Power Distance

The first of Geert Hofstede’s original dimensions of national cultures was power distance, or the degree to which those people and organizations with less power within a culture accept and expect that power is unequally distributed within their culture. When it comes to power distances, these differences often manifest themselves in many ways within a singular culture: class, education, occupations, and health care. With class, many cultures have three clear segments low, middle, and upper. However, the concepts of what is low, middle, and upper can have very large differences. For example, the median income for the average U.S. household is $51,100.24 When discussing household incomes, we use the median (middlemost number) because it’s the most accurate representation of income. According to a 2013 report from the U.S. Census department (using income data from 2012), here is how income inequality in the U.S. looks:

Households in the lowest quintile had incomes of $20,599 or less in 2012. Households in the second quintile had incomes between $20,600 and $39,764, those in the third quintile had incomes between $39,765 and $64,582, and those in the fourth quintile had incomes between $64,583 and $104,096. Households in the highest quintile had incomes of $104,097 or more. The top 5 percent had incomes of $191,157 or more.25

However, income is just one indicatory of power distance within a culture. Others are who gets educated and what type of education they receive, who gets health care and what type, and what types of occupations do those with power have versus those who do not have power.

According to Hofstede’s most recent data, the five countries with the highest power distances are: Malaysia, Slovakia, Guatemala, Panama, and the Philippines.26 The five countries with the lowest power distances are Austria, Israel, Denmark, New Zealand, and Switzerland (German-speaking part). Notice that the U.S. does not make it into the top five or the bottom five. According to Hofstede’s data, the U.S. is 16th from the bottom of power distance, so we are in the bottom third with regards to power distance. When it comes down to it, despite the issues we have in our country, the power disparity is not nearly as significant as it is in many other parts of our world.

Individualism vs. Collectivism

The United States is number one on individualism, according to Hofstede’s data.27 Americans are considered individualistic. In other words, we think about ourselves as individuals rather than the collective group. Most Asian countries are considered collectivistic cultures because these cultures tend to be group-focused. Collectivistic cultures tend to think about actions that might affect the entire group rather than specific members of the group.

In an individualistic culture, there is a belief that you can do what you want and follow your passions. In an individualistic culture, if someone asked what you do for a living, they would answer by saying their profession or occupation. However, in collectivistic cultures, a person would answer in terms of the group, organization, and/or corporation that they serve. Moreover, in a collectivistic culture, there is a belief that you should do what benefits the group. In other words, collectivistic cultures focus on how the group can grow and be productive.

Masculinity vs. Femininity

The notion of masculinity and femininity are often misconstrued to be tied to their biological sex counterparts, female and male. For understanding culture, Hofstede acknowledges that this distinction ultimately has a lot to do with work goals.28 On the masculine end of the spectrum, individuals tend to be focused on items like earnings, recognition, advancement, and challenge. Hofstede also refers to these tendencies as being more assertive. Femininity, on the other hand, involves characteristics like having a good working relationship with one’s manager and coworkers, cooperating with people at work, and security (both job and familial). Hofstede refers to this as being more relationally oriented. Admittedly, in Hofstede’s research, there does tend to be a difference between females and males on these characteristics (females tend to be more relationally oriented and males more assertive), which is why Hofstede went with the terms masculinity and femininity in the first place. Ultimately, we can define these types of cultures in the following way:

A society is called masculine when emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with quality of life.

A society is called feminine when emotional gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with quality of life [emphasis in original].29

The top five most masculine countries are Slovakia, Japan, Hungary, Austria, and Venezuela (the U.S. is number 19 out of 76); whereas, feminine countries are represented by Sweden, Norway, Latvia, Netherlands, and Denmark. As you can imagine, depending on the type of culture you live in, you will have wildly different social interactions with other people. There’s also a massive difference in the approach to marriage. In masculine cultures, women are the caretakers of the home, while men are to be healthy and wealthy. As such, women are placed in a subservient position to their husbands are often identified socially by their husbands. For example, an invitation to a party would be addressed to “Mr. and Mrs. John Smith.” In feminine cultures, men and women are upheld to the same standards, and their relationships should be based on mutual friendship.

Low vs. High Uncertainty Avoidance

The next category identified by Hofstede involves the concept of uncertainty avoidance.30 Life is full of uncertainty. We cannot escape it; however, some people are more prone to becoming fearful in situations that are ambiguous or unknown. Uncertainty avoidance then involves the extent to which cultures as a whole are fearful of ambiguous and unknown situations.

People in cultures with high uncertainty avoidance can view this ambiguity and lack of knowledge as threatening, which is one reason why people in these cultures tend to have higher levels of anxiety and neuroticism as a whole. Cultures at the high end of uncertainty avoidance include Greece, Portugal, Guatemala, Uruguay, and Belgium Flemish; whereas, cultures at the low end of uncertainty avoidance include Singapore, Jamaica, Denmark, Sweden, and Hong Kong. The United States ranks 64th out of 76 countries analyzed (Singapore was number 76).

From an interpersonal perspective, people from high uncertainty avoidant cultures are going to have a lot more anxiety associated with interactions involving people from other cultures. Furthermore, there tend to be higher levels of prejudice and higher levels of ideological, political, and religious fundamentalism, which does not allow for any kind of debate.

Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation

In addition to the previous characteristics, Hofstede noticed a fifth characteristic of cultures that he deemed long-term and short-term orientation. Long-term orientation focuses on the future and not the present or the past. As such, there is a focus on both persistence and thrift. The emphasis on endurance is vital because being persistent today will help you in the future. The goal is to work hard now, so you can have the payoff later. The same is true of thrift. We want to conserve our resources and under-spend to build that financial cushion for the future.

Short-term oriented cultures, on the other hand, tend to focus on both the past and the present. In these cultures, there tends to be high respect for the past and the various traditions that have made that culture great. Additionally, there is a strong emphasis on “saving face,” which we will discuss more in the next section, fulfilling one’s obligations today, and enjoying one’s leisure time.

At the long-term end of the spectrum are countries like China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Japan; whereas, countries like Pakistan, Czech Republic, Nigeria, Spain, and the Philippines are examples of short-term. The United States ranked 31 out of 39, with Pakistan being number 39. Interpersonally, long-term oriented countries were more satisfied with their contributions to “Being attentive to daily human relations, deepening human bonds in family, neighborhood and friends or acquaintances” when compared to their short-term counterparts.32

Indulgence vs. Restraint

The sixth cultural characteristic is called indulgence vs. restraint, which examines issues of happiness and wellbeing. According to Hofstede and his coauthors, “Indulgence stands for a tendency to allow relatively free gratification of basic and natural human desires related to enjoying life and having fun. Its opposite pole, restraint, reflects a conviction that such gratification needs to be curbed and regulated by strict social norms.”34 The top five on the Indulgence end are Venezuela, Mexico, Puerto Rico, El Salvador, and Nigeria, whereas those on the restraint end are Pakistan, Egypt, Latvia, Ukraine, and Albania. The U.S. is towards the indulgence end of the spectrum and ranks at #15 along with Canada and the Netherlands. Some interesting findings associated with indulgence include experiencing higher levels of positive emotions and remembering those emotions for more extended periods. Furthermore, individuals from more indulgent cultures tend to be more optimistic, while their restrained counterparts tend to be more cynical. People in more indulgent countries are going to be happier than their restrained counterparts, and people within indulgent cultures show lower rates of cardiovascular problems commonly associated with stress. Finally, individuals from indulgent cultures tend to be more extraverted and outgoing as a whole, whereas individuals from restrained cultures tend to be more neurotic. From years of research examining both extraversion and neuroticism, we know that extraverted individuals have more successful interpersonal relationships than those who are highly neurotic. Ultimately, research examining these differences have shown that people from indulgent countries are more open to other cultures, more satisfied with their lives, and are more likely to communicate with friends and family members via the Internet while interacting with more people from other cultures via the Internet as well.

Face-Negation Theory

The basic idea behind face-negotiation theory is that face-saving, conflict, and culture are all intertwined. In the most recent version of her theory, Stella Ting-Toomey outlines seven basic factors of face-negotiation theory:

- People in all cultures try to maintain and negotiate face in all communication situations.

- The concept of face is especially problematic in emotionally vulnerable situations (such as embarrassment, request, or conflict situations) when the situation identities of the communicators are called into question.

- The cultural variability dimensions of individualism-collectivism and small/large power distance shape the orientations, movements, contents, and styles of facework.

- Individualism-collectivism shapes members’ preferences for self-oriented facework versus other-oriented facework.

- Small/large power distance shapes members’ preferences for horizontal-based facework versus vertical-based facework.

- The cultural variability dimensions, in conjunction with individual, relational, and situational factors influence the use of particular facework behaviors in particular cultural scenes.

- Intercultural facework competence refers to the optimal integration of knowledge, mindfulness, and communication skills in managing vulnerable identity-based conflict situations appropriately, effectively, and adaptively.38

First and foremost, communication and face are highly intertwined concepts, so when coming to an intercultural encounter, it is important to remember the interrelationship between the two. Face-negotiation theory ultimately concerned with three different types of face: self-face (concern for our face), other-face (concern for another person’s face), and mutual-face (concern for both interactants and the relationship).39 Individuals who are competent in facework can recognize when facework is necessary and then handle those situations appropriately, effectively, and adaptively. As such, facework should be viewed as a necessary component for understanding any form of interpersonal interaction but is especially important when examining interpersonal interactions that occur between people from differing cultural backgrounds.

What is Face?

The concept of face is one that is not the easiest to define nor completely understand. Originally, the concept of face is not a Western even though the idea of “saving face” is pretty common in every day talk today. According to Hsien Chin Hu, the concept of face stems from two distinct Chinese words, lien and mien-tzu.40 Lien “represents the confidence of society in the integrity of ego’s moral character, the loss of which makes it impossible for him to function properly within the community. Lien is both a social sanction for enforcing moral standards and an internalized sanction.”41 On the other hand, mien-tzu “stands for the kind of prestige that is emphasized in this country [America]: a reputation achieved through getting on in life, through success and ostentation.”42

Face is essentially “a person’s reputation and feelings of prestige within multiple spheres, including the workplace, the family, personal friends, and society at large.”44 For our purposes, we can generally break face down into general categories: face gaining and face losing. Face gaining refers to the strategies a person might use to build their reputation and feelings of prestige (e.g., talking about accomplishments, active social media presence, etc.), whereas face losing refers to those behaviors someone engages in that can harm their reputation or feelings of prestige (e.g., getting caught in a lie, failing, etc.).

Key Takeaways

- Low-context cultures are cultures where the emphasis is placed on the words that come out of an individual’s mouth. High-context cultures, on the other hand, are cultures where understanding a message is dependent on the cultural context and a communicator’s nonverbal behavior.

- Geert Hofstede’s research created a taxonomy for understanding and differentiating cultures. Hofstede found that cultures could be differentiated by power distance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity vs. femininity, uncertainty avoidance, long-term vs. short-term orientation, and indulgence vs. restraint.

- Face is the standing or position a person has in the eyes of others. During an interpersonal interaction, individuals strive to create a positive version of their face for the other person.

Improving Intercultural Communication Skills

Become Culturally Intelligent

One of the latest buzz-words in the business world is “cultural intelligence,” which was initially introduced to the scholarly community in 2003 by P. Christopher Earley and Soon Ang.45 In the past decade, a wealth of research has been conducted examining the importance of cultural intelligence during interpersonal interactions with people from other cultures. Cultural intelligence (CQ) is defined as an “individual’s capability to function effectively in situations characterized by cultural diversity.”46

Four Factors of Cultural Intelligence

In their original study on the topic, Earley and Ang argued that cultural intelligence is based on four distinct factors: cognitive, motivational, metacognitive, and behavioral dimensions.

Cognitive CQ

First, cognitive CQ involves knowing about different cultures (intercultural knowledge). Many types of knowledge about a culture can be relevant during an intercultural interaction: rules and norms, economic and legal systems, cultural values and beliefs, the importance of art within a society, etc.… All of these different areas of knowledge involve facts that can help you understand people from different cultures.

For example, in most of the United States, when you are talking to someone, eye contact is very important. You may have even been told by someone to “look at me when I’m talking to you” if you’ve ever gotten in trouble. However, this isn’t consistent across different cultures at all. Hispanic, Asian, Middle Eastern, and Native American cultures often view direct contact when talking to someone superior as a sign of disrespect. Knowing how eye contact functions across cultures can help you know more about how to interact with people from various cultures.

Motivational CQ

Second, we have motivational CQ, or the degree to which an individual desires to engage in intercultural interactions and can easily adapt to different cultural environments. Motivation is the key to effective intercultural interactions. You can have all the knowledge in the world, but if you are not motivated to have successful intercultural interactions, you will not have them.

Metacognitive CQ

Third, metacognitive CQ involves being consciously aware of your intercultural interactions in a manner that helps you have more effective interpersonal experiences with people from differing cultures (intercultural understanding). All of the knowledge about cultural differences in the world will not be beneficial if you cannot use that information to understand and adapt your behavior during an interpersonal interaction with someone from a differing culture. As such, we must always be learning about cultures but also be ready to adjust our knowledge about people and their cultures through our interactions with them.

Behavioral CQ

Lastly, behavioral CQ is the next step following metacognitive CQ, which is behaving in a manner that is consistent with what you know about other cultures.48 We should never expect others to adjust to us culturally. Instead, culturally intelligent people realize that it’s best to adapt our behaviors (verbally and nonverbally) to bridge the gap between people culturally. When we go out of our way to be culturally intelligent, we will encourage others to do so as well.

As you can see, becoming a truly culturally intelligent person involves a lot of work. As such, it’s important to spend time and build your cultural intelligence if you are going to be an effective communicator in today’s world.

Key Takeaways

- Cultural intelligence involves the degree to which an individual can communicate competently in varying cultural situations. Cultural intelligence consists of four distinct parts: knowledge, motivation, understanding, and behavior.

Key Terms

behavioral CQ

The degree to which an individual behaves in a manner that is consistent with what they know about other cultures.

belief

Assumptions and convictions held by an individual, group, or culture about the truth or existence of something.

co-culture

Regional, economic, social, religious, ethnic, or other cultural groups that exerts influence in society.

cognitive CQ

The degree to which an individual has cultural knowledge.

collective self-esteem

The aspect of an individual’s self-worth or self-image that stems from their interaction with others and evaluation of their various social groups.

collectivism

Characteristics of a culture that values cooperation and harmony and considers the needs of the group to be more important than the needs of the individual.

cultural intelligence

The degree to which an individual can communicate competently in varying cultural situations.

culture

A group of people who, through a process of learning, can share perceptions of the world, which influence their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.

culture as normative

The basic idea that one’s culture provides the rules, regulations, and norms that govern a culture and how people act with other members of that society.

dominant culture

The established language, religion, behavior, values, rituals, and social customs of a society.

ethnocentrism

The degree to which an individual views the world from their own culture’s perspective while evaluating different cultures according to their own culture’s preconceptions often accompanied by feelings of dislike, mistrust, or hate for cultures deemed inferior.

face

The standing or position a person has in the eyes of others.

feminine

Cultures focused on having a good working relationship with one’s manager and coworkers, cooperating with people at work, and security (both job and familial).

high-context cultures

Cultures that interpret meaning by relying more on nonverbal context or behavior than on verbal symbols in communication.

importance to identity

The degree to which group membership is important to an individual.

indigenous peoples

Populations that originated in a particular place rather than moved there.

individualism

Characteristics of a culture that values being self-reliant and self-motivated, believes in personal freedom and privacy, and celebrates personal achievement.

indulgence

Cultural orientation marked by immediate gratification for individual desires.

long-term orientation

Cultural orientation where individuals focus on the future and not the present or past.

low-context cultures

Cultures that interpret meaning by placing a great deal of emphasis on the words someone uses.

masculine

Cultures focused on items like earnings, recognition, advancement, and challenge.

membership esteem

The degree to which an individual sees themself as a “good” member of a group.

metacognitive CQ

The degree to which an individual is consciously aware of their intercultural interactions in a manner that helps them have more effective interpersonal experiences with people from differing cultures.

microculture

Cultural patterns of behavior influenced by cultural beliefs, values, norms, and rules based on a specific locality or within an organization.

motivational CQ

The degree to which an individual desires to engage in intercultural interactions and can easily adapt to differing cultural environments.

norms

Informal guidelines about what is acceptable or proper social behavior within a specific culture.

power distance

The degree to which those people and organizations with less power within a culture accept and expect that power is unequally distributed within their culture.

private collective esteem

The degree to which an individual positively evaluates their group.

public collective self-esteem

The degree to which nonmembers of a group evaluate a group and its members either positively or negatively.

restraint

Cultural orientation marked by the belief that gratification should not be instantaneous and should be regulated by cultural rules and norms.

rules

Explicit guidelines (generally written down) that govern acceptable or proper social behavior within a specific culture.

short-term orientation

Cultural orientation where individuals focus on the past or present and not in the future.

stereotype

A set of beliefs about the personal attributes of a social group.

uncertainty avoidance

The extent to which cultures as a whole are fearful of ambiguous and unknown situations.

values

Important and lasting principles or standards held by a culture about desirable and appropriate courses of action or outcomes.

Chapter Wrap-Up

In this chapter, we started by discussing what the word “culture” means while also considering the concepts of co-culture and microcultures. We then looked at the critical functions that culture performs in our daily lives. Next, we discussed the intersection of culture and communication. Lastly, we ended this chapter discussing how you can improve your intercultural communication skills.

Notes

A group of people who through a process of learning can share perceptions of the world that influences their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.

Assumptions and convictions held by an individual, group, or culture about the truth or existence of something.

Important and lasting principles or standards held by a culture about desirable and appropriate courses of action or outcomes.

Informal guidelines about what is acceptable or proper social behavior within a specific culture.

Explicit guidelines (generally written down) that govern acceptable or proper social behavior within a specific culture.

Regional, economic, social, religious, ethnic, or other cultural groups that exerts influence in society.

Cultural patterns of behavior influenced by cultural beliefs, values, norms, and rules based on a specific locality or within an organization.

The aspect of an individual’s self-worth or self-image that stems from their interaction with others and evaluation of their various social groups.

The degree to which an individual positively evaluates their group.

The degree to which an individual sees themself as a “good” member of a group.

The degree to which nonmembers of a group evaluate a group and its members either positively or negatively.

The degree to which group membership is important to an individual.

A set of beliefs about the personal attributes of a social group.

The degree to which an individual views the world from their own culture’s perspective while evaluating different cultures according to their own culture’s preconceptions often accompanied by feelings of dislike, mistrust, or hate for cultures deemed inferior.

The standing or position a person has in the eyes of others.