Conflict in Relationships

Conflict is a normal and natural part of life. However, learning how to manage conflict in our interpersonal relationships is very important for long-term success in those relationships. This chapter looks at how conflict functions and provide several strategies for managing interpersonal conflict.

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between the terms conflict, disagreement, and argument.

- Explain the interrelationships among emotions and feelings.

- Describe emotional awareness and its importance to interpersonal communication.

- Differentiate between “I” and “You” statements.

- Explain the five common styles of conflict management

- Recognize the Four Horsemen of the Relational Apocalypse

- Understand and apply the STLC Conflict Model

Understanding Conflict

For our purposes, it is necessary to differentiate a conflict from a disagreement.1 A disagreement is a difference of opinion and often occurs during an argument, or a verbal exchange between two or more people who have differing opinions on a given subject or subjects. It’s important to realize that arguments are not conflicts, but if they become verbally aggressive, they can quickly turn into conflicts. One factor that ultimately can help determine if an argument will escalate into a conflict is an individual’s tolerance for disagreement. James McCroskey and colleagues defined tolerance for disagreement as whether an individual can openly discuss differing opinions without feeling personally attacked or confronted.2,3 People that have a high tolerance for disagreement can easily discuss opinions with pretty much anyone and realize that arguing is perfectly normal and, for some, even entertaining. People that have a low tolerance for disagreement feel personally attacked any time someone is perceived as devaluing their opinion. From an interpersonal perspective, understanding someone’s tolerance for disagreement can help in deciding if arguments will be perceived as the other as attacks that could lead to verbally aggressive conflicts. However, not all conflict is necessarily verbally aggressive nor destructive.

The term “conflict” is actually very difficult to define. Simplistically, conflict is an interactive process occurring when individuals or groups have opposing or incompatible actions, beliefs, goals, ideas, motives, needs, objectives, obligations resources and/or values. First, conflict is interactive and inherently communicative. Second, two or more people or even groups of people must be involved. Lastly, there are a whole range of different areas where people can have opposing or incompatible opinions. For this generic definition, we provided a laundry list of different types of incompatibility that can exist between two or more individuals or groups. Is this list completely exhaustive? No. But we provided this list as a way of thinking about the more common types of issues that are raised when people engage in conflict. From this perspective, everything from a minor disagreement to a knock-down, drag-out fight would classify as a conflict.

Two Perspectives on Conflict

As with most areas of interpersonal communication, no single perspective exists in the field related to interpersonal conflict. There are generally two very different perspectives that one can take. On the one hand, you had scholars who see conflict as a disruption in a normal working system, which should be avoided. On the other hand, some scholars view conflict as a normal part of human relationships.4 Let’s look at each of these in this section.

Perspective 1: Conflict Disrupts Working Systems

The first major perspective of conflict was proposed by McCroskey and Wheeless who described conflict as a negative phenomenon in interpersonal relationships:

Conflict between people can be viewed as the opposite or antithesis of affinity. In this sense, interpersonal conflict is the breaking down of attraction and the development of repulsion, the dissolution of perceived homophily (similarity) and the increased perception of incompatible differences, the loss of perceptions of credibility and the development of disrespect. 6

From this perspective, conflict is something inherently destructive. McCroskey and Richmond went further and argued that conflict is characterized by antagonism, distrust, hostility, and suspicion.7

This negative view of conflict differentiates itself from a separate term, disagreement, which is simply a difference of opinion between two or more people or groups of people. Richmond and McCroskey note that there are two types of disagreements: substantive and procedural.8 A substantive disagreement is a disagreement that people have about a specific topic or issue. Basically, if you and your best friend want to go eat at two different restaurants for dinner, then you’re engaging in a substantive disagreement. On the other hand, procedural disagreements are “concerned with procedure, how a decision should be reached or how a policy should be implemented.”9 So, if your disagreement about restaurant choice switches to a disagreement on how to make a choice (flipping a coin vs. rock-paper-scissors), then you’ve switched into a procedural disagreement.

In this view, conflict is a disagreement plus negative affect; not only do you disagree with someone else, you don’t like the other person. It’s the combination of a disagreement and dislike that causes a mere disagreement to turn into a conflict. Ultimately, conflict is a product of how one communicates this dislike of another person during the disagreement. People in some relationships end up saying very nasty things to one another during a disagreement because their affinity for the other person has diminished. When conflict is allowed to continue and escalate, it “can be likened to an ugly, putrid, decaying, pus-filled sore.”10

From this perspective, conflicts are ultimately only manageable; whereas, disagreements can be solved. Although a disagreement is the cornerstone of all conflicts, most disagreements don’t turn into conflicts because there is an affinity between the two people engaged in the disagreement.

Perspective 2: Conflict is a Normal Part of Human Communication

The second perspective of the concept of conflict is very different from the first one. Cahn and Abigail contend conflict is a normal, inevitable part of life.11 In this view, conflict is one of the foundational building blocks of interpersonal relationships. One can even ask if it’s possible to grow in a relationship without conflict. Managing and overcoming conflict makes a relationship stronger and healthier. Ideally, when interpersonal dyads engage in conflict management (or conflict resolution), they will reach a solution that is mutually beneficial for both parties. In this manner, conflict can help people seek better, healthier outcomes within their interactions.

In this view, conflict is neither good nor bad, but it’s a tool that can be used for constructive or destructive purposes. Conflict can be very beneficial and healthy for a relationship. Let’s look at how conflict is beneficial for individuals and relationships:

- Conflict helps people find common ground.

- Conflict helps people learn how to manage conflict more effectively for the future.

- Conflict provides the opportunity to learn about the other person(s).

- Conflict can lead to creative solutions to problems.

- Confronting conflict allows people to engage in an open and honest discussion, which can build relationship trust.

- Conflict encourages people to grow both as humans and in their communication skills.

- Conflict can help people become more assertive and less aggressive.

- Conflict can strengthen individuals’ ability to manage their emotions.

- Conflict lets individuals set limits in relationships.

- Conflict lets us practice our communication skills.

When one approaches conflict from this vantage point, conflict can be seen as a helpful resource in interpersonal relationships. However, both parties must agree to engage in prosocial conflict management strategies for this to work effectively.

Interpersonal Conflict

According to Cahn and Abigail, interpersonal conflict requires four factors to be present:

- the conflict parties are interdependent,

- they have the perception that they seek incompatible goals or outcomes or they favor incompatible means to the same ends,

- the perceived incompatibility has the potential to adversely affect the relationship leaving emotional residues if not addressed, and

- there is a sense of urgency about the need to resolve the difference. 12

Let’s look at each of these parts of interpersonal conflict separately.

People are Interdependent

According to Cahn and Abigail, “interdependence occurs when those involved in a relationship characterize it as continuous and important, making it worth the effort to maintain.”13 From this perspective, interpersonal conflict occurs when we are in some kind of relationship with another person. For example, it could be a relationship with a parent/guardian, a child, a coworker, a boss, a spouse, etc. In each of these interpersonal relationships, we generally see ourselves as having long-term relationships with these people that we want to succeed. We may have disagreements and arguments with all kinds of strangers, but those don’t rise to the level of interpersonal conflicts.

Differing Goals, Differing Means to the Same End

An incompatible goal occurs when two people want different things. For example, imagine you and your best friend are thinking about going to the movies. They want to see a big-budget superhero film, and you’re more in the mood for an independent artsy film. In this case, you have pretty incompatible goals (movie choices). You can also have incompatible means to reach the same end. Incompatible means, in this case, “occur when we want to achieve the same goal but differ in how we should do so.”14 For example, you and your best friend agree on going to the same movie, but not about at which theatre you should see the film.

Negative Effects When Unaddressed

Next, interpersonal conflicts can lead to very negative outcomes if the conflicts are not managed effectively. Here are some, of many, possible examples of conflicts that are not managed effectively:

- One partner dominates the conflict, and the other partner caves-in.

- One partner yells or belittles the other partner.

- One partner uses half-truths or lies to get her/his/their way during the conflict.

- Both partners only want to get their way at all costs.

- One partner refuses to engage in conflict.

Again, this is a sample laundry list of some of the ways where conflict can be mismanaged. When conflict is mismanaged, one or both partners can start to have less affinity for the other partner, which can lead to a decreasing in liking, decreased caring about the relational partner, increased desire to exit the relationship, increased relational apathy, increased revenge-seeking behavior, etc. All of these negative outcomes could ultimately lead to conflicts becoming increasingly more aggressive (both active and passive) or just outright conflict avoidance.

Role of Urgency in Resolving Conflict

Lastly, there must be some sense of urgency to resolve the conflict within the relationship. Conflict must get to the point where it needs attention, and a decision must be made or an outcome decided upon, or else. Conflict can escalate if it is not resolved. Indeed, some people let conflicts stir and rise over many years that can eventually boil over, but these types of conflicts when they arise generally have some other kind of underlying conflict that is causing the sudden explosion. For example, imagine your spouse has a particularly quirky habit. For the most part, you ignore this habit and may even make a joke about the habit. Finally, one day you just explode and demand the habit must change. Now, it’s possible that you let this conflict build for so long that it finally explodes. It’s kind of like a geyser. According to Yellowstone National Park, here’s how a geyser works:

The looping chambers trap steam from the hot water. Escaped bubbles from trapped steam heat the water column to the boiling point. When the pressure from the trapped steam builds enough, it blasts, releasing the pressure. As the entire water column boils out of the ground, more than half the volume is this steam. The eruption stops when the water cools below the boiling point.15

In the same way, sometimes people let irritations or underlying conflict percolate inside of them until they reach a boiling point, which leads to the eventual release of pressure in the form of a sudden, ‘out of nowhere’ conflict. In this case, even though the conflict has been building for some time, the eventual desire to make this conflict known to the other person does cause an immediate sense of urgency for the conflict to be solved.

Emotions, Feelings, and Needs in Conflict

Emotions and feelings relate to harmony and discord in a relationship, so it’s important to differentiate between ethe two. Emotions are our biophysical reactions to stimuli in the outside environment. This definition assumes emotions can be objectively measured by blood flow, brain activity, skin conductance, and nonverbal reactions to things. Feelings, on the other hand, are the responses to thoughts and interpretations given to emotions based on experiences, memory, expectations, and personality. So, there is an inherent relationship between emotions and feelings, but we do differentiate between them. Table 1 breaks down the differences between the two concepts.

| © John W. Voris, CEO of Authentic Systems, www.authentic-systems.com Reprinted here with permission. |

|

| Emotions: | Feelings: |

|---|---|

| Emotions tell us what we “like” and “dislike.” | Feelings tell us “how to live.” |

| Emotions state: “There are good and bad actions.” | Feelings state: “There is a right and wrong way to be.“ |

| Emotions state: “The external world matters.” | Feelings state: “your emotions matter.” |

| Emotions establish our initial attitude toward reality. | Feelings establish our long-term attitude toward reality. |

| Emotions alert us to immediate dangers and prepare us for action. | Feelings alert us to anticipated dangers and prepares us for action. |

| Emotions ensure immediate survival of self (body and mind). | Feelings ensure long-term survival of self (body and mind). |

| Emotions are Intense but Temporary. | Feelings are Low-key but Sustainable. |

| Joy: is an emotion. | Happiness: is a feeling. |

| Fear: is an emotion. | Worry: is a feeling. |

| Enthusiasm: is an emotion. | Contentment: is a feeling. |

| Anger: is an emotion. | Bitterness: is a feeling. |

| Lust: is an emotion. | Love: is a feeling. |

| Sadness: is an emotion. | Depression: is a feeling. |

Table 1 Differentiating Emotions and Feelings

It’s important to understand that we are all emotional beings. Being emotional is an inherent part of being a human. That’s why we should avoid phrases like “don’t feel that way” or “they have no right to feel that way.” When we negate someone else’s emotions, we are negating that person as an individual and taking away their right to emotional responses. At the same time, though, no one else can make you “feel” a specific way. Our emotions are our emotions. They are how we interpret and cope with life. A person may set up a context where you experience an emotion, but you are the one who is still experiencing that emotion and allowing yourself to experience that emotion. If you don’t like “feeling” a specific way, then change it. We all have the ability to alter our emotions. Altering our emotional states (in a proactive way) is how we get through life. Maybe you just broke up with someone, and listening to music helps you work through the grief you are experiencing to get to a better place. For others, they need to openly communicate about how they are feeling in an effort to process and work through emotions. The worst thing a person can do is attempt to deny that the emotion exists.

Other research has demonstrated that handling negative emotions during conflicts within a marriage (especially on the part of the wife) can lead to faster de-escalations of conflicts and faster conflict mediation between spouses.16 Our emotions often (but not always) translate into feelings.

Emotional Awareness

Some people are better at recognizing and managing their emotions than others, we call this emotional awareness. Emotional awareness, or an individual’s ability to clearly express, in words, what they are feeling and why, is an extremely important factor in effective interpersonal communication. Unfortunately, our emotional vocabulary is often quite limited. One extreme version of of not having an emotional vocabulary is called alexithymia, “a general deficit in emotional vocabulary—the ability to identify emotional feelings, differentiate emotional states from physical sensations, communicate feelings to others, and process emotion in a meaningful way.”17 Furthermore, there are many people who can accurately differentiate emotional states but lack the actual vocabulary for a wide range of different emotions. For some people, their emotional vocabulary may consist of good, bad, angry, and fine. Learning how to communicate one’s emotions is very important for effective interpersonal relationships.18 First, it’s important to distinguish between our emotional states and how we interpret an emotional state the feelings that ensue. For example, you can feel sad or bitter, which may prompt you to feel alienated. Your sadness and bitterness may lead you to perceive yourself as alienated, but alienation is a perception of one’s self and not an actual emotional state.

“You” Statements Reveal How We Talk Matters

According to Marshall Rosenberg, the father of nonviolent communication, “You” statements ultimately are moralistic judgments where we imply the wrongness or badness of another person and the way they have behaved.19 When we make moralistic judgments about others, we tend to deny responsibility for our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Remember, when it comes to feelings, no one can “make” you feel a specific way. We choose the feelings we inhabit; we do not inhabit the feelings that choose us. When we make moralistic judgments and deny responsibility, we end up creating and perpetuating cycles of defensiveness where your individual needs are not going to be met by your relational partner. Behind every negative emotion is a need not being fulfilled, and when we start blaming others, those needs will keep getting unfilled in the process. Often this lack of need fulfillment will result in us demanding someone fulfill our need or face blame or punishment. For example, “if you go hang out with your friends tonight, I’m going to hurt myself and it will your fault.” In this simple sentence, we see someone who disapproves of another’s behaviors and threatens to blame their relational partner for the individual’s behavior. In highly volatile relationships, this constant blame cycle can become very detrimental, and no one’s needs are getting met.

If you have heard about “you” statements it’s likely you’ve also heard about one solution to them: Using “I” statements. “I” statements focus on articulating your feelings and emotions. However, just observing behavior and stating how you feel only gets you part of the way there because you’re still not describing your need.

Needs and Conflict

When we talk about the idea of “needing” something, we are not talking about this strictly in terms of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, though those are all entirely appropriate needs. At the same time, relational needs are generally not rewards like tangible items or money. Instead, Rosenberg categorizes basic needs that we all have falling into the categories: autonomy, celebration, play, spiritual communion, physical nurturance, integrity, and interdependence (Table 2). As you can imagine, any time these needs are not being met, you will reach out to get them fulfilled. As such, when we communicate about our feelings, they are generally tied to an unmet or fulfilled need. For example, you could say, “I feel dejected when you yell at me because I need to be respected.” In this sentence, you are identifying your need, observing the behavior, and labeling the need. Notice that there isn’t judgment associated with identifying one’s needs.

| Area | Need |

|---|---|

| Autonomy | to choose one’s dreams, goals, values |

| to choose one’s plan for fulfilling one’s dreams, goals, values | |

| Celebration | to celebrate the creation of life and dreams fulfilled |

| to celebrate losses: loved ones, dreams, etc. (mourning) | |

| Play | fun |

| laughter | |

| Spiritual Communion | beauty |

| harmony | |

| inspiration | |

| order | |

| peace | |

| Physical Nurturance | air |

| food | |

| movement, exercise | |

| protection from life-threatening forms of life: viruses, bacteria, insects, predatory animals | |

| rest | |

| sexual expression | |

| shelter | |

| touch | |

| water | |

| Integrity | authenticity |

| creativity | |

| meaning | |

| self-worth | |

| Interdependence | acceptance |

| appreciation | |

| closeness | |

| community | |

| consideration | |

| contribution to the enrichment of life (to exercise one’s power by giving that which contributes to life) | |

| emotional safety | |

| empathy | |

| honesty (the empowering honest that enables us to learn from our limitations) | |

| love | |

| reassurance | |

| respect | |

| support | |

| trust | |

| understanding | |

| warmth | |

| Source: Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life 2nd Ed by Dr. Marshall B. Rosenberg, 2003–published by PuddleDancer Press and Used with Permission. For more information visit www.CNVC.org and www.NonviolentCommunication.com |

|

Table 2 Needs

Research Spotlight

In 2020, researchers Anna Wollny, Ingo Jacobs, and Luise Pabel set out to examine the impact that trait EQ has on both relationship satisfaction and dyadic coping. Dyadic coping is based on Guy Bodenmann’s Systemic Transactional Model (STM), which predicts that stress in dyadic relationships is felt by both partners.21 So, if one partner experiences the stress of a job loss, that stress really impacts both partners. As a result, both partners can engage in mutual shared problem-solving or joint emotion-regulation.22 According to Bodenmann, there are three different common forms of dyadic coping:

In 2020, researchers Anna Wollny, Ingo Jacobs, and Luise Pabel set out to examine the impact that trait EQ has on both relationship satisfaction and dyadic coping. Dyadic coping is based on Guy Bodenmann’s Systemic Transactional Model (STM), which predicts that stress in dyadic relationships is felt by both partners.21 So, if one partner experiences the stress of a job loss, that stress really impacts both partners. As a result, both partners can engage in mutual shared problem-solving or joint emotion-regulation.22 According to Bodenmann, there are three different common forms of dyadic coping:

- Positive dyadic coping involves the provision of problem- and emotion-focused support and reducing the partner’s stress by a new division of responsibilities and contributions to the coping process.

- Common dyadic coping (i.e., joint dyadic coping) includes strategies in which both partners jointly engage to reduce stress (e.g., exchange tenderness, joint problem-solving).

- Negative dyadic coping comprises insufficient support and ambivalent or hostile intervention attempts (e.g., reluctant provision of support while believing that the partner should solve the problem alone).23

In the Wollny et al. (2000) study, the researchers studied 136 heterosexual couples. Trait EQ was positively related to relationship satisfaction. Trait EQ was positively related to positive dyadic coping and common dyadic coping but not related to negative dyadic coping.

Wollny, A., Jacobs, I., & Pabel, L. (2020). Trait emotional intelligence and relationship satisfaction: The mediating role of dyadic coping. The Journal of Psychology, 154(1), 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2019.1661343

Gottman’s Four Horseman of the Relational Apocalypse

In the study of interpersonal communication, understanding conflict and its resolution is crucial. Psychologist John Gottman identified four negative communication patterns that predict relationship failure, which he termed the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.” These behaviors are Criticism, Contempt, Defensiveness, and Stonewalling. Gottman’s research, based on decades of observing couples, provides a framework for recognizing and addressing destructive patterns in relationships. 51

Criticism

Criticism involves attacking a partner’s character or personality rather than focusing on specific behaviors. It often begins with phrases like “You always” or “You never,” making it personal and generalized rather than situational. This pattern can erode the foundation of respect and understanding in a relationship. Criticism is prevalent in many relationships and is linked to increased relational dissatisfaction and the emergence of other negative behaviors. 51

Example: “You never think about how your actions affect others. You’re so selfish.”

Avoiding Criticism: Use a gentle startup by expressing feelings and stating a positive need. For instance, “I feel hurt when plans change without notice. Can we communicate better about our schedules?”

Contempt

Contempt is the most damaging of the Four Horsemen and involves expressing disdain or superiority. This can be through sarcasm, name-calling, eye-rolling, or hostile humor. Contempt conveys disrespect and creates a toxic emotional climate. According to Gottman, contempt is the single greatest predictor of divorce. Couples who exhibit contempt are more likely to divorce than those who do not. 52 Additionally, contemptuous behavior can negatively impact the immune system, with couples engaging in such exchanges experiencing higher stress levels and greater susceptibility to illness. 51

Example: “Oh, you’re tired? You do nothing all day, unlike me.”

Avoiding Contempt: Build a culture of appreciation and respect by regularly expressing gratitude and acknowledging your partner’s efforts and qualities.

Defensiveness

Defensiveness occurs when one responds to perceived criticism by counter-attacking or playing the victim. This behavior escalates conflicts rather than resolving them and often involves making excuses or denying responsibility. Defensiveness is strongly correlated with conflict escalation, perpetuating cycles of argumentation and misunderstanding. 52 Couples who frequently exhibit defensiveness are less likely to resolve conflicts effectively, leading to prolonged disputes and increased relational strain.

Example: “It’s not my fault we’re late. You always take forever to get ready.”

Avoiding Defensiveness: Accept responsibility, even if it’s partial. Respond with, “I see why you’re upset. Let’s figure out how we can manage our time better.”

Stonewalling

Stonewalling happens when one partner withdraws from the interaction, shutting down and refusing to engage. This can be a response to feeling overwhelmed, but it leads to a lack of resolution and emotional distance. Stonewalling is more commonly observed in men than in women, as men are more likely to withdraw during conflict to self-soothe and avoid emotional flooding.53 It is associated with increased physiological stress markers, such as elevated heart rate and blood pressure, which can further impede effective communication and conflict resolution. 51

Example: One partner stops responding, avoids eye contact, and remains silent during an argument.

Avoiding Stonewalling: Take a break to calm down and then return to the conversation. Practice self-soothing techniques and agree on a time to revisit the discussion constructively.

Longitudinal research by Gottman and colleagues has demonstrated that the presence of the Four Horsemen in early stages of marriage is predictive of marital stability or instability over time. Couples exhibiting high levels of these negative behaviors early on are more likely to divorce within the first six years of marriage. 53 Interventions aimed at reducing the Four Horsemen and promoting positive communication behaviors have been shown to improve relationship satisfaction and decrease the likelihood of divorce. Couples who learn to replace criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling with healthier communication strategies report higher levels of marital satisfaction. 51

Maintaining a positive-to-negative interaction ratio is essential for the health of relationships. Gottman’s research indicates that successful relationships generally maintain a ratio of 5:1—five positive interactions for every negative one. This ratio is crucial for creating a positive emotional climate and mitigating the impact of negative interactions. In contrast, couples in distress often exhibit a ratio of 0.8:1, indicating more negative than positive interactions. 51

Conflict Management Strategies

Many researchers have attempted to understand how humans handle conflict with one another. Thomas’s model focuses on the behavior individuals engage in when confronted with conflict. 54 Parties to a conflict attempt to implement their resolution mode by competing or accommodating in the hope of resolving problems. A major task here is determining how best to proceed strategically. That is, what tactics will the party use to attempt to resolve the conflict? Thomas has identified five modes for conflict resolution: (1) competing, (2) collaborating, (3) compromising, (4) avoiding, and (5) accommodating (see Table 3).

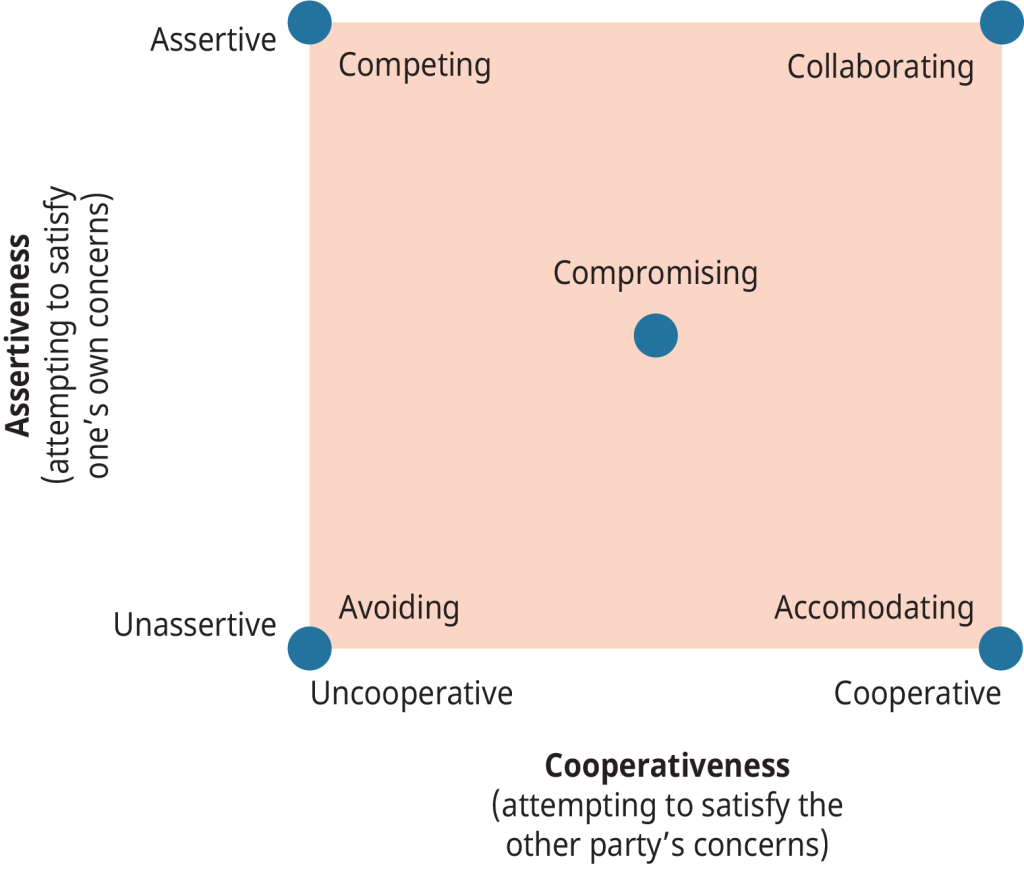

The choice of an appropriate conflict resolution mode depends to a great extent on the situation and the goals of the party (see Figure 1). According to this model, each party must decide the extent to which it is interested in satisfying its own concerns—called assertiveness—and the extent to which it is interested in helping satisfy the opponent’s concerns—called cooperativeness. Assertiveness can range from assertive to unassertive on one continuum, and cooperativeness can range from uncooperative to cooperative on the other continuum.

Once the parties have determined their desired balance between the two competing concerns—either consciously or unconsciously—the resolution strategy emerges. For example, if a union negotiator feels confident she can win on an issue that is of primary concern to union members (e.g., wages), a direct competition mode may be chosen (see the upper left-hand corner of Figure 1). On the other hand, when the union is indifferent to an issue or when it actually supports management’s concerns (e.g., plant safety), we would expect an accommodating or collaborating mode (on the right-hand side of the figure).

| Table 3 — Five Modes of Resolving Conflict | |

|---|---|

| Conflict-Handling Modes | Appropriate Situations |

| Source: Adapted from Thomas (1976). (Credit: Rice University/OpenStax/CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) | |

| Competing |

|

| Collaborating |

|

| Compromising |

|

| Avoiding |

|

| Accommodating |

|

What is interesting in this process is the assumptions people make about their own modes compared to their opponents’. For example, in one study of executives, it was found that the executives typically described themselves as using collaboration or compromise to resolve conflict, whereas these same executives typically described their opponents as using a competitive mode almost exclusively. 55 In other words, the executives underestimated their opponents’ concerns as uncompromising. Simultaneously, the executives had flattering portraits of their own willingness to satisfy both sides in a dispute.

Finally, as a result of efforts to resolve the conflict, both sides determine the extent to which a satisfactory resolution or outcome has been achieved. Where one party to the conflict does not feel satisfied or feels only partially satisfied, the seeds of discontent are sown for a later conflict, as shown in the preceding figure. One unresolved conflict episode can easily set the stage for a second episode. Action aimed at achieving quick and satisfactory resolution is vital; failure to initiate such action leaves the possibility (more accurately, the probability) that new conflicts will soon emerge.

The last type of conflicting partners are collaborators. There are a range of collaborating choices, from being completely collaborative in an attempt to find a mutually agreed upon solution, to being compromising when you realize that both sides will need to win and lose a little to come to a satisfactory solution. In both cases, the goal is to use prosocial communicative behaviors in an attempt to reach a solution everyone is happy with. Admittedly, this is often easier said than done. Furthermore, it’s entirely possible that one side says they want to collaborate, and the other side refuses to collaborate at all. When this happens, collaborative conflict management strategies may not be as effective, because it’s hard to collaborate with someone who truly believes you need to lose the conflict.

Alan Sillars and colleagues created a taxonomy of different types of strategies that people can use when collaborating during a conflict. Table 10 provides a list of these common tactics. 45

| Conflict Management Tactics | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Acts | Statements that describe obvious events or factors. | “Last time your sister babysat our kids, she yelled at them.” |

| Qualification | Statements that explicitly explain the conflict. | “I am upset because you didn’t come home last night.” |

| Disclosure | Statements that disclose one’s thoughts and feelings in a non-judgmental way. | “I get really worried when you don’t call and let me know where you are.” |

| Soliciting Disclosure | Questions that ask another person to disclose their thoughts and feelings. | “How do you feel about what I just said?” |

| Negative Inquiry | Statements allowing for the other person to identify your negative behaviors. | “What is it that I do that makes you yell at me?” |

| Empathy | Statements that indicate you understand and relate to the other person’s emotions and experiences. | “I know this isn’t easy for you.” |

| Emphasize Commonalities | Statements that highlight shared goals, aims, and values. | “We both want what’s best for our son.” |

| Accepting Responsibility | Statements acknowledging the part you play within a conflict. | “You’re right. I sometimes let my anger get the best of me.” |

| Initiating Problem-Solving | Statements designed to help the conflict come to a mutually agreed upon solution. | “So let’s brainstorm some ways that will help us solve this.” |

| Concession | Statements designed to give in or yield to a partner’s goals, aims, or values. | “I promise, I will make sure my homework is complete before I watch television.” |

Table 10 Integrative Conflict Management Strategies

STLC Conflict Model

Abigail and Cahn created a very simple model when thinking about how we communicate during conflict.47 They called the model the STLC Conflict Model because it stands for stop, think, listen, and then communicate (see Figure 3).

Stop

The first thing an individual needs to do when interacting with another person during conflict is to take the time to be present within the conflict itself. Too often, people engaged in a conflict say whatever enters their mind before they’ve really had a chance to process the message and think of the best strategies to use to send that message. Others end up talking past one another during a conflict because they simply are not paying attention to each other and the competing needs within the conflict. Communication problems often occur during conflict because people tend to react to conflict situations when they arise instead of being mindful and present during the conflict itself. For this reason, it’s always important to take a breath during a conflict and first stop.

Sometimes these “time outs” need to be physical. Maybe you need to leave the room and go for a brief walk to calm down, or maybe you just need to get a glass of water. Whatever you need to do, it’s important to take this break. This break takes you out of a “reactive stance into a proactive one.” 48

Think

Once you’ve stopped, you now have the ability to really think about what you are communicating. You want to think through the conflict itself. What is the conflict really about? Often people engage in conflicts about superficial items when there are truly much deeper issues that are being avoided. You also want to consider what possible causes led to the conflict and what possible courses of action you think are possible to conclude the conflict. Cahn and Abigail argue that there are four possible outcomes that can occur: do nothing, change yourself, change the other person, or change the situation.

First, you can simply sit back and avoid the conflict. Maybe you’re engaging in a conflict about politics with a family member, and this conflict is actually just going to make everyone mad. For this reason, you opt just to stop the conflict and change topics to avoid making people upset. One of our coauthors was at a funeral when an uncle asked our coauthor about our coauthor’s impression of the current President. Our coauthor’s immediate response was, “Do you really want me to answer that question?” Our coauthor knew that everyone else in the room would completely disagree, so our coauthor knew this was probably a can of worms that just didn’t need to be opened.

Second, we can change ourselves. Often, we are at fault and start conflicts. We may not even realize how our behavior caused the conflict until we take a step back and really analyze what is happening. When it comes to being at fault, it’s very important to admit that you’ve done wrong. Nothing is worse (and can stoke a conflict more) than when someone refuses to see their part in the conflict.

Third, we can attempt to change the other person. Let’s face it, changing someone else is easier said than done. Just ask your parents/guardians! All of our parents/guardians have attempted to change our behaviors at one point or another, and changing people is very hard. Even with the powers of punishment and reward, a lot of time change only lasts as long as the punishment or the reward. One of our coauthors was in a constant battle with our coauthors’ parents about thumb sucking as a child. Our coauthor’s parents tried everything to get the thumb sucking to stop. They finally came up with an ingenious plan. They agreed to buy a toy electric saw if their child didn’t engage in thumb sucking for the entire month. Well, for a whole month, no thumb sucking occurred at all. The child got the toy saw, and immediately inserted the thumb back into our coauthor’s mouth. This short story is a great illustration of the problems that can be posed by rewards. Punishment works the same way. As long as people are being punished, they will behave in a specific way. If that punishment is ever taken away, so will the behavior.

Lastly, we can just change the situation. Having a conflict with your roommates? Move out. Having a conflict with your boss? Find a new job. Having a conflict with a professor? Drop the course. Admittedly, changing the situation is not necessarily the first choice people should take when thinking about possibilities, but often it’s the best decision for long-term happiness. In essence, some conflicts will not be settled between people. When these conflicts arise, you can try and change yourself, hope the other person will change (they probably won’t, though), or just get out of it altogether.

Listen

The third step in the STLC model is listen. Humans are not always the best listeners. As discussed in other parts of this textbook, listening is a skill. Unfortunately, during a conflict situation, this is a skill that is desperately needed and often forgotten. When we feel defensive during a conflict, our listening becomes spotty at best because we start to focus on ourselves and protecting ourselves instead of trying to be empathic and seeing the conflict through the other person’s eyes.

One mistake some people make is to think they’re listening, but in reality, they’re listening for flaws in the other person’s argument. We often use this type of selective listening as a way to devalue the other person’s stance. In essence, we will hear one small flaw with what the other person is saying and then use that flaw to demonstrate that obviously everything else must be wrong as well.

The goal of listening must be to suspend your judgment and really attempt to be present enough to accurately interpret the message being sent by the other person. When we listen in this highly empathic way, we are often able to see things from the other person’s point-of-view, which could help us come to a better-negotiated outcome in the long run.

Communicate

Lastly, but certainly not least, we communicate with the other person. Cahn and Abigail put communication as the last part of the STLC model because it’s the hardest one to do effectively during a conflict if the first three are not done correctly. When we communicate during a conflict, we must be hyper-aware of our nonverbal behavior (eye movement, gestures, posture, etc.). Nothing will kill a message faster than when it’s accompanied by bad nonverbal behavior. For example, rolling one’s eyes while another person is speaking is not an effective way to engage in conflict.

During a conflict, it’s important to be assertive and stand up for your ideas without becoming verbally aggressive. Conversely, you have to be open to someone else’s use of assertiveness as well without having to tolerate verbal aggression. We often end up using mediators to help call people on the carpet when they communicate in a fashion that is verbally aggressive or does not further the conflict itself. As Cahn and Abigail note, “People who are assertive with one another have the greatest chance of achieving mutual satisfaction and growth in their relationship.” 49

Mindfulness Activity

The STLC Model for Conflict is definitely one that is highly aligned with our discussion of mindful interpersonal relationships within this book. Taylor Rush, a clinical psychologist working for the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Neuro-Restoration, recommends seven considerations for ensuring mindfulness while engaged in conflict:

The STLC Model for Conflict is definitely one that is highly aligned with our discussion of mindful interpersonal relationships within this book. Taylor Rush, a clinical psychologist working for the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Neuro-Restoration, recommends seven considerations for ensuring mindfulness while engaged in conflict:

- Set intentions. What do you want to be discussed during this interaction? What do you want to learn from the other person? What do you want to happen as a result of this conversation? Set your intentions early and check-in along to way to keep the conversation on point.

- Stay present to the situation. Try to keep assumptions at bay and ask open-ended questions to better understand the other person’s perspective and experiences.

- Stay aware of your inner reactions. Disrupt the automatic feedback loop between your body and your thoughts. Acknowledge distressing or judgmental thoughts and feelings without reacting to them. Then check them against the facts of the situation.

- Take one good breath before responding. A brief pause can mean all the difference between opting for a thoughtful response or knee-jerk reaction.

- Use reflective statements. This is a tried and true strategy for staying present. It allows you to fully concentrate on what the other person is saying (rather than form your rebuttal) and shows the other person you have an interest in what they are actually saying. This will make them more likely to reciprocate!

- Remember, it’s not all about you. The ultimate objective is that both parties are heard and find the conversation beneficial. Try to actively take the other person’s perspective and cultivate compassion (even if you fundamentally do not agree with their position). This makes conflict escalation much less likely.

- Investigate afterward. What do you feel now that the conversation is over? What was the overall tone of the conversation? Do you feel like you understand the other person’s perspective? Do they understand yours? Will this require further conversation or has the issue been resolved? Asking these questions will help you to hone your practice for the future.50

For this activity, we want you to think back to a recent conflict that you had with another person (e.g., coworker, friend, family member, romantic partner, etc.). Answer the following questions:

- If you used the STLC Model for Conflict, how effective was it for you? Why?

- If you did not use the STLC Model for Conflict, do you think you could have benefited from this approach? Why?

- Looking at Rush’s seven strategies for engaging in mindful conflict, did you engage in all of them? If you didn’t engage in them all, which ones did you engage in, and which ones didn’t you engage in? How could engaging in all seven of them helped your conflict management with this person?

- If you haven’t already, take a moment to think about the questions posed in #7 of Rush’s list. What can you learn from this conflict that will help prepare you for future conflicts with this person or future conflicts more broadly?

Key Takeaways

- A conflict occurs when two people perceive differing goals or values, and if the two parties do not reach a solution, the interpersonal relationship could be seriously fractured. An argument, on the other hand, is a difference of opinion that occurs between two people during an argument. The primary difference between a conflict and an argument involves the emotional volatility of the situation. However, individuals with a low tolerance for disagreement may perceive any form of argument as interpersonal conflict.

- Emotions are our physical reactions to stimuli in the outside environment; whereas, feelings are the responses to thoughts and interpretations given to emotions based on experiences, memory, expectations, and personality.

- Emotional awareness involves an individual’s ability to recognize their feelings and communicate about them effectively. One of the common problems that some people have with regards to emotional awareness is a lack of a concrete emotional vocabulary for both positive and negative feelings. When people cannot adequately communicate about their feelings, they will never get what they need out of a relationship.

- One common problem in interpersonal communication is the overuse of “You” statements. “I” statements are statements that take responsibility for how one is feeling. “You” statements are statements that place the blame of one’s feelings on another person. Remember, another person cannot make you feel a specific way. Furthermore, when we communicate “you” statements, people tend to become more defensive, which could escalate into conflict.

- Thomas’ Conflict Management Grid suggests there are multiple ways to approach conflict, none is superior but each balances one’s own and a partner’s needs.

- Gottman’s four horsemen of the relational apocalypse are strong predictors of relational failure due to repeated conflict.

- Dudley Cahn and Ruth Anna Abigail’s STLC method for communication is very helpful when working through conflict with others. STLC stands for stop, think, listening, and communicate. Stop and time to be present within the conflict itself and prepare. Think through the real reasons for the conflict and what you want as an outcome for the conflict. Listen to what the other person says and try to understand the conflict from their point-of-view. Communicate in a manner that is assertive, constructive, and aware of your overall message.

Key Terms

accidental communication

When an individual sends messages to another person without realizing those messages are being sent.

alexithymia

A general deficit in emotional vocabulary—the ability to identify emotional feelings, differentiate emotional states from physical sensations, communicate feelings to others, and process emotion in a meaningful way.

argument

A verbal exchange between two or more people who have differing opinions on a given subject or subjects.

avoidance

Conflict management style where an individual attempt to either prevent a conflict from occurring or leaves a conflict when initiated.

coercive power

The ability to punish an individual who does not comply with one’s influencing attempts.

compliance

When an individual accepts an influencer’s influence and alters their thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors.

conflict

An interactive process occurring when conscious beings (individuals or groups) have opposing or incompatible actions, beliefs, goals, ideas, motives, needs, objectives, obligations, resources, and/or values.

disagreement

A difference of opinion between two or more people or groups of people.

distributive conflict

A win-lose approach, whereby conflicting parties see their job as to win and make sure the other person or group loses.

Dunning–Kruger effect

The tendency of some people to inflate their expertise when they really have nothing to back up that perception.

emotional awareness

An individual’s ability to clearly express, in words, what they are feeling and why.

emotions

The physical reactions to stimuli in the outside environment.

emotional intelligence

An individual’s appraisal and expression of their emotions and the emotions of others in a manner that enhances thought, living, and communicative interactions.

expert power

The ability of an individual to influence another because of their level of perceived knowledge or skill.

expressive communication

Messages that are sent either verbally or nonverbally related to an individual’s emotions and feelings.

feelings

The responses to thoughts and interpretations given to emotions based on experiences, memory, expectations, and personality.

identification

When an individual accepts influence because they want to have a satisfying relationship with the influencer or influencing group.

influence

When an individual or group of people alters another person’s thinking, feelings, and/or behaviors through accidental, expressive, or rhetorical communication.

informational power

A social agent’s ability to bring about a change in thought, feeling, and/or behavior through information.

integrative conflict

A win-win approach to conflict, whereby both parties attempt to come to a settled agreement that is mutually beneficial.

interdependence

When individuals involved in a relationship characterize it as continuous and important.

internalization

When an individual adopts influence and alters their thinking, feeling, and/or behaviors because doing so is intrinsically rewarding.

legitimate power

Influence that occurs because a person (P) believes that the social agent (A) has a valid right (generally based on cultural or hierarchical standing) to influence P, and P has an obligation to accept A’s attempt to influence P’s thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors.

power

The degree that a social agent (A) has the ability to get another person(s) (P) to alter their thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors.

procedural disagreements

Disagreements concerned with procedure, how a decision should be reached or how a policy should be implemented.

referent power

A social agent’s (A) ability to influence another person (P) because P wants to be associated with A.

reward power

The ability to offer an individual rewards for complying with one’s influencing attempts.

rhetorical communication

Purposefully creating and sending messages to another person in the hopes of altering another person’s thinking, feelings, and/or behaviors.

substantive disagreement

A disagreement that people have about a specific topic or issue.

tolerance for disagreement

The degree to which an individual can openly discuss differing opinions without feeling personally attacked or confronted.

“you” statements

Moralistic judgments where we imply the wrongness or badness of another person and the way they have behaved.

Key Takeaways

- The terms disagreement and argument are often confused with one another. For our purposes, the terms refer to unique concepts. A disagreement is a difference of opinion between two or more people or groups of people; whereas, an argument is a verbal exchange between two or more people who have differing opinions on a given subject or subjects.

- There are two general perspectives regarding the nature of conflict. The first perspective sees conflict as a disruption to normal working systems, so conflict is inherently something that is dangerous to relationships and should be avoided. The second perspective sees conflict as a normal, inevitable part of any relationship. From this perspective, conflict is a tool that can either be used constructively or destructively in relationships.

- According to Cahn and Abigail, interpersonal conflict consists of four unique parts: 1) interdependence between or among the conflict parties, (2) incompatible goals/means, (3) conflict can adversely affect a relationship if not handled effectively, and (4) there is a sense of urgency to resolve the conflict.

Notes

Chapter Attribution:

A difference of opinion between two or more people or groups of people.

A verbal exchange between two or more people who have differing opinions on a given subject or subjects.

The degree to which an individual can openly discuss differing opinions without feeling personally attacked or confronted.

An interactive process occurring when conscious beings (individuals or groups) have opposing or incompatible actions, beliefs, goals, ideas, motives, needs, objectives, obligations, resources, and/or values.

A disagreement that people have about a specific topic or issue.

Disagreements concerned with procedure, how a decision should be reached or how a policy should be implemented.

When individuals involved in a relationship characterize it as continuous and important.

The physical reactions to stimuli in the outside environment.

The responses to thoughts and interpretations given to emotions based on experiences, memory, expectations, and personality.

An individual’s ability to clearly express, in words, what they are feeling and why.

A general deficit in emotional vocabulary—the ability to identify emotional feelings, differentiate emotional states from physical sensations, communicate feelings to others, and process emotion in a meaningful way.