Perception and the Self

Who are you? Have you ever sat around thinking about how you fit into the larger universe. A simple exercise helps to get at the heart of this question.1 Use the worksheet in the workbook and answer “Who am I?” with the worksheet numbered 1 to 20. Results from this activity generally demonstrate five distinct categories about an individual: social group an individual belongs to, ideological beliefs, personal interests, personal ambitions, and self-evaluations. All of these five categories are happening at what is called the intrapersonal-level. Intrapersonal refers to something that exists or occurs within an individual’s self or mind.

This chapter focuses on understanding perception and the self and how they relate to communication. Intrapersonal communication refers to communication phenomena that exist within or occurs because of an individual’s self or mind. The chapter highlights how in addition to personality, one’s biologically based temperament also plays an important role in how they interact with others interpersonally. Temperament is identifiable at birth, whereas, personality is something that develops over one’s lifespan. Although we cannot change the biological aspects of our temperament, we can learn how to adjust our behaviors in light of our temperaments.

Perception Processes

Learning Objectives

-

- Describe and explain the three stages of the perception process.

- Differentiate between self-concept and self-esteem.

- Explain what is meant by Cooley’s concept of the looking-glass self.

- Define and differentiate between the terms personality and temperament.

- List and explain the different social, personal, and relational dispositions which affect dispositions.

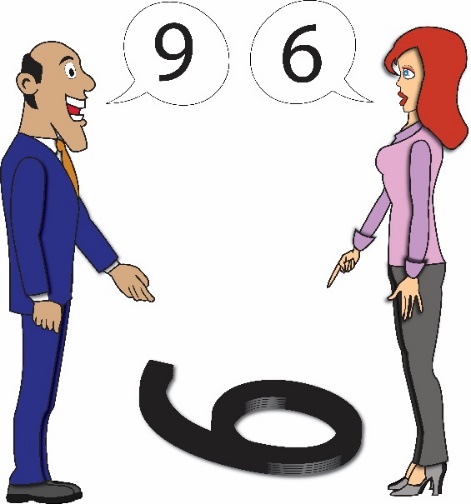

As you can see from Figure 1, how you view something is also how you will describe and define it. Your perception of something will determine how you feel about it and how you will communicate about it. In Figure 1, do you see it as a six or a nine? Why did you answer the way that you did?

Your perceptions affect who you are, and they are based on your experiences and preferences. If you have a horrible experience with a restaurant, you probably won’t go to that restaurant in the future. You might even tell others not to go to that restaurant based on your personal experience. Thus, it is crucial to understand how perceptions can influence others.

Sometimes the silliest arguments occur with others because we don’t understand their perceptions of things. Thus, it is important to make an effort to see things the way that the other person does. In other words, put yourself in their shoes and see it from their perspective before jumping to conclusions or getting upset. That person might have a legitimate reason why they are not willing to concede with you.

Perception

Many of our problems in the world occur due to perception, or the process of acquiring, interpreting, and organizing information that comes in through your five senses. When we don’t get all the facts, it is hard to make a concrete decision. We have to rely on our perceptions to understand the situation. In this section, you will learn tools that can help you understand perceptions and improve your communication skills. As you will see in many of the illustrations on perception, people can see different things. In some of the pictures, some might only be able to see one picture, but there might be others who can see both images, and a small amount might be able to see something completely different from the rest of the class.

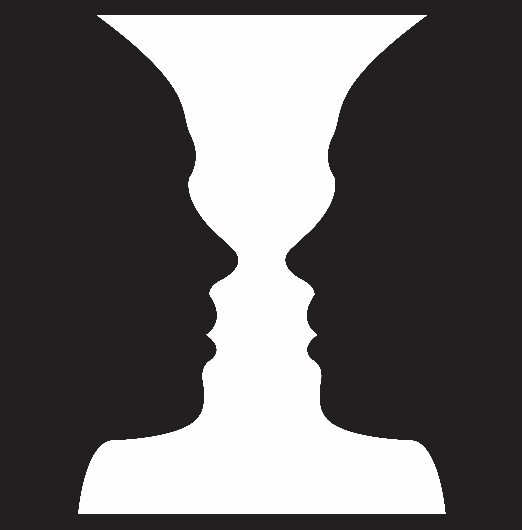

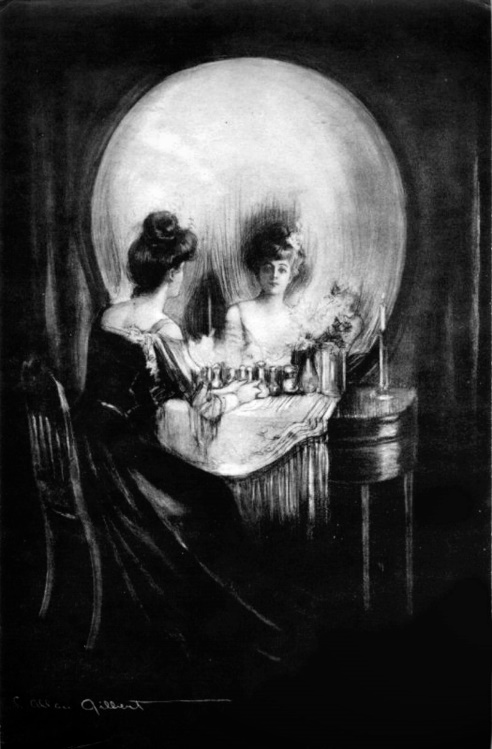

Many famous artists over the years have played with people’s perceptions. Figure 2a, 2b, and 2c are an example of three artists’ use of twisted perceptions. In the first picture, The Rubin Vase, there is what appears to either be a vase (the white part) or two people looking at each other (the black part). This simple image is both two images and neither image at the same time. The second work is called “All is Vanity.” In this painting, you can see a woman sitting staring at herself in the mirror. At the same time, the image is also a giant skull. Lastly, “My Wife and My Mother-in-Law,” shows two different images, one of a young woman and one of an older woman. These visual images are helpful reminders that we don’t always perceive things in the same way as those around us. There are often multiple ways to view and understand the same set of events.

When it comes to interpersonal communication, each time you talk to other people, you present a side of yourself. Sometimes this presentation is a true representation of yourself, and other times it may be in inauthentic version of yourself. People present themselves how they want others to see them. Some people present themselves positively on social media, and they have wonderful relationships. Then, their followers or fans get shocked to learn when those i

mages are not true to what is presented. If we only see one side of things, we might be surprised to learn that things are different. The perception process has three stages: attending, organizing, and interpreting.

Attending

The first step of the perception process is to select what information you want to pay attention to or focus on, which is called attending. We attend to things based on how they look, feel, smell, touch, and taste. At every moment, you are obtaining a large amount of information. So, how do you decide what you want to pay attention to and what you choose to ignore? People will tend to pay attention to things that matter to them. Usually, we pay attention to things that are louder, larger, different, and more complex to what we ordinarily view.

Due to our limited cognitive abilities we are always focusing on a particular things and ignoring other things in a process called selective perception. For instance, when you are in love, you might pay attention to only that special someone and not notice anything else. The same thing happens when we end a relationship, and we are devasted, we might see how everyone else is in a great relationship, but we aren’t.

There are a couple of reasons why you pay attention to certain things more so than others: We often pay attention to something is because it is extreme or intense. In other words, it stands out of the crowd and captures our attention, like an extremely good looking person at a party or a big neon sign in a dark, isolated town. We can’t help but notice these things because they are exceptional or extraordinary in some way. Second, we pay attention to things that are different or contradicting. We are quick to notice something that we are not used to or something that no longer exists for you. For instance, if you had someone very close to you pass away, then you might pay more attention to the loss of that person than to anything else. Some people grieve for an extended period because they were so used to having that person around, and things can be different since you don’t have them to rely on or ask for input.

The third thing that we pay attention to is something that repeats over and over again. Think of a catchy song or a commercial that continually repeats itself. We might be more alert to it since it repeats, compared to something that was only said once. The fourth thing that we will pay attention to is based on our motives. If we have a motive to find a romantic partner, we might be more perceptive to other attractive people than normal, because we are looking for romantic interests. Another motive might be to lose weight, and you might pay more attention to exercise advertisements and food selection choices compared to someone who doesn’t have the motive to lose weight. Our motives influence what we pay attention to and what we ignore.

The last thing that influences our selection process is our emotional state. If we are in an angry mood, then we might be more attentive to things that get us angrier. As opposed to, if we are in a happy mood, then we will be more likely to overlook a lot of negativity because we are already happy. Selective perception doesn’t involve just paying attention to certain cues. It also means that you might be overlooking other things. For instance, people in love will think their partner is amazing and will overlook a lot of their flaws. This is normal behavior. We are so focused on how wonderful they are that we often will neglect the other negative aspects of their behavior.

Organizing

Look again at the three images in Figure 2. What were the first things that you saw when you looked at each picture? Could you see the two different images? Which image was more prominent? When we examine a picture or image, we engage in organizing it in our head to make sense of it and define it. After we select the information that we are paying attention to, we have to make sense of it in our brains. Information can be organized in different ways. After we attend to something, our brains quickly want to make sense of this data. We quickly want to understand the information that we are exposed to and organize it in a way that makes sense to us.

There are four types of schemes that people use to organize perceptions.2 First, physical constructs are used to classify people (e.g., young/old; tall/short; big/small). Second, role constructs are social positions (e.g., mother, friend, lover, doctor, teacher). Third, interaction constructs are the social behaviors displayed in the interaction (e.g., aggressive, friendly, dismissive, indifferent). Fourth, psychological constructs are the dispositions, emotions, and internal states of mind of the communicators (e.g., depressed, confident, happy, insecure). We often use these schemes to better understand and organize the information that we have received. We use these schemes to generalize others and to classify information.

Let’s pretend that you came to class and noticed that one of your classmates was wildly waving their arms in the air at you. This will most likely catch your attention because you find this behavior strange. Then, you will try to organize or makes sense of what is happening. Once you have organized it in your brain, you will need to interpret the behavior.

Interpreting

The final stage of the perception process is interpreting. In this stage of perception, you are attaching meaning to understand the data. So, after you select information and organize things in your brain, you have to interpret the situation. As previously discussed in the above example, your friend waves their hands wildly (attending), and you are trying to figure out what they are communicating to you (organizing). You will attach meaning (interpreting). Does your friend need help and is trying to get your attention, or does your friend want you to watch out for something behind you?

We interpret other people’s behavior daily. Walking to class, you might see an attractive stranger smiling at you. You could interpret this as a flirtatious behavior or someone just trying to be friendly. Scholars have identified some factors that influence our interpretations:3

Attribution Error

Attribution error is defined as the tendency to explain another individual’s behavior in relation to the individual’s internal tendencies rather than an external factor.13 For example, if a friend is late, we might attribute this failure to be on time as the friend being irresponsible rather than running through a list of external factors that may have influenced the friend’s ability to be on time such as an emergency, traffic, read the time wrong, etc. It is easy to make an error when trying to attribute meaning to the behaviors of others.

Personal Experience

Personal experience also impacts our interpretation of events. What prior experiences have you had that affect your perceptions? Maybe you heard from your friends that a particular restaurant was really good, but when you went there, you had a horrible experience, and you decided you never wanted to go there again. Even though your friends might try to persuade you to try it again, you might be inclined not to go, because your past experience with that restaurant was not good.

Another example might be a traumatic relationship break up. You might have had a relational partner that cheated on you and left you with trust issues. You might find another romantic interest, but in the back of your mind, you might be cautious and interpret loving behaviors differently, because you don’t want to be hurt again.

Involvement

Degree of involvement impacts your interpretation. The more involved or deeper your relationship is with another person, the more likely you will interpret their behaviors differently compared to someone you do not know well. For instance, let’s pretend that you are a manager, and two of your employees come to work late. One worker just happens to be your best friend and the other person is someone who just started and you do not know them well. You are more likely to interpret your best friend’s behavior more altruistically than the other worker because you have known your best friend for a longer period. Besides, since this person is your best friend, this implies that you interact and are more involved with them compared to other friends.

Expectations

Expectations that we hold can impact the way we make sense of other people’s behaviors. For instance, if you overheard some friends talking about a mean professor and how hostile they are in class, you might be expecting this to be true. Let’s say you meet the professor and attend their class; you might still have certain expectations about them based on what you heard. Even those expectations might be completely false, and you might still be expecting those allegations to be true.

Assumptions

We make assumptions about human behavior. Imagine if you are a personal fitness trainer, do you believe that people like to exercise or need to exercise? Your answer to that question might be based on your assumptions. If you are a person who is inclined to exercise, then you might think that all people like to work out. However, if you do not like to exercise but know that people should be physically fit, then you would more likely agree with the statement that people need to exercise. Your assumptions about humans can shape the way that you interpret their behavior. Another example might be that if you believe that most people would donate to a worthy cause, you might be shocked to learn that not everyone thinks this way. When we assume that all humans should act a certain way, we are more likely to interpret their behavior differently if they do not respond in a certain way.

Relational Satisfaction

Last relational satisfaction will make you see things very differently. Relational satisfaction is how satisfied or happy you are with your current relationship. If you are content, then you are more likely to view all your partner’s behaviors as thoughtful and kind. However, if you are not satisfied in your relationship, then you are more likely to view their behavior has distrustful or insincere. Research has shown that unhappy couples are more likely to blame their partners when things go wrong compared to happy couples.14

Who Are You?

Self-Concept

According to Baumeister (1999), self-concept implies “the individual’s belief about [their self], including the person’s attributes and who and what the self is.”4 An attribute is a characteristic, feature, or quality or inherent part of a person, group, or thing.

In 1968, social psychologist Norman Anderson came up with a list of 555 personal attributes.5 He had research participants rate the 555 attributes from most desirable to least desirable. The top ten most desirable characteristics were:

- Sincere

- Honest

- Understanding

- Loyal

- Truthful

- Trustworthy

- Intelligent

- Dependable

- Open-Minded

- Thoughtful

Conversely, the top ten least desirable attributes were:

- Liar

- Phony

- Mean

- Cruel

- Dishonest

- Untruthful

- Obnoxious

- Malicious

- Dishonorable

- Deceitful

When looking at this list, do you agree with the ranks from 1968? In a more recent study, conducted by Jesse Chandler using an expanded list of 1,042 attributes,6 the following pattern emerged for the top 10 most positively viewed attributes:

- Honest

- Likable

- Compassionate

- Respectful

- Kindly

- Sincere

- Trustworthy

- Ethical

- Good-Natured

- Honorable

And here is the updated list for the top 10 most negatively viewed attributes:

- Pedophilic

- Homicidal

- Evil-Doer

- Abusive

- Evil-Minded

- Nazi

- Mugger

- Asswipe

- Untrustworthy

- Hitlerish

Some of the changes in both lists represent changing times and the addition of the new terms by Chandler. For example, the terms sincere, honest, and trustworthy were just essential attributes for both the 1968 and 2018 studies. Conversely, none of the negative attributes remained the same from 1968 to 2018. The negative attributes, for the most part, represent more modern sensibilities about personal attributes.

The Three Selves

Carl Rogers argued an individual’s self-concept is made of three distinct things: self-image, self-worth, and ideal-self.7

Self-Image

An individual’s self-image is a view that they have of themselves. If we go back and look at the attributes that we’ve listed in this section, think about these as laundry lists of possibilities that impact your view of yourself. For example, you may view yourself as ethical, trustworthy, honest, and loyal, but you may also realize that there are times when you are also obnoxious and mean. For a positive self-image, we will have more positive attributes than negative ones. However, it’s also possible that one negative attribute may overshadow the positive attributes, which is why we also need to be aware of our perceptions of our self-worth.

Self-Worth

Self-worth is the value that you place on yourself. In essence, self-worth is the degree to which you see yourself as a good person who deserves to be valued and respected. Unfortunately, many people judge their self-worth based on arbitrary measuring sticks like physical appearance, net worth, social circle/clique, career, grades, achievements, age, relationship status, likes on Facebook, social media followers, etc.… Interested in seeing how you view your self-worth? Then take a minute and complete the Contingencies of Self-Worth Scale.8 According to Courtney Ackerman, there are four things you can do to help improve your self-worth:9

- You no longer need to please other people.

- No matter what people do or say, and regardless of what happens outside of you, you alone control how you feel about yourself.

- You have the power to respond to events and circumstances based on your internal sources, resources, and resourcefulness, which are the reflection of your true value.

- Your value comes from inside, from an internal measure that you’ve set for yourself.

Ideal-Self

The final characteristic of Rogers’ three parts to self-concept is the ideal-self.10 The ideal-self is the version of yourself that you would like to be, which is created through our life experiences, cultural demands, and expectations of others. The real-self, on the other hand, is the person you are. The ideal-self is perfect, flawless, and, ultimately, completely unrealistic. When an individual’s real-self and ideal-self are not remotely similar, someone needs to think through if that idealized version of one’s self is attainable. It’s also important to know that our ideal-self is continuously evolving. How many of us wanted to be firefighters, police officers, or astronauts as kids? Some of you may still want to be one of these, but most of us had our ideal-self evolve.

The “Looking-Glass” Self

Charles Horton Cooley’s looking-glass self argues: “Each to each a looking-glass / Reflects the other that doth pass”11 Although the term “looking-glass” isn’t used very often in today’s modern tongue, it means a mirror. Cooley argues, when we are looking to a mirror, we also think about how others view us and the judgments they make about us. Cooley posed three postulates:

- Actors learn about themselves in every situation by exercising their imagination to reflect on their social performance.

- Actors next imagine what those others must think of them. In other words, actors imagine the others’ evaluations of the actor’s performance.

- The actor experiences an affective reaction to the imagined evaluation of the other.12

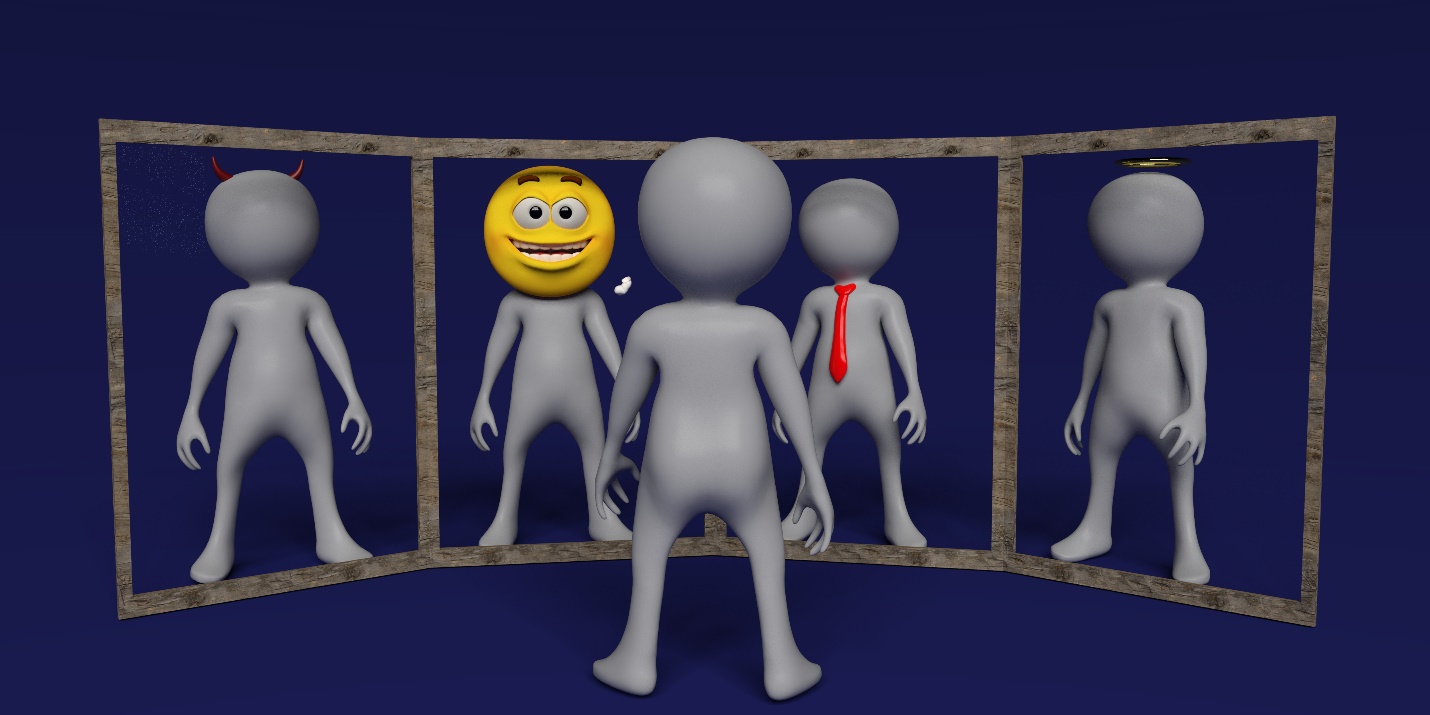

Figure 3 presents an illustration of this basic idea. You have a figure standing before four glass panes. In the left-most mirror, the figure has devil horns; in the second, a pasted on a fake smile; in the third, a tie; and in the last one, a halo. Maybe the figure’s ex sees the devil, his friends and family think the figure is always happy, the figure’s coworkers see a professional, and the figure’s parents/guardians see their little angel. Along with each of these ideas, there are inherent judgments. And, not all of these judgments are necessarily accurate, but we still come to understand and know ourselves based on our perceptions of these judgments.

Ultimately, our self-image is shaped through our interactions with others, but only through the mediation of our minds. At the same time, because we perceive that others are judging us, we also tend to shape our façade to go along with that perception. For example, if you work in the customer service industry, you may sense that you are always expected to smile. Since you want to be viewed positively, you plaster on a fake smile all the time no matter what is going on in your personal life. At the same time, others may start to view you as a happy-go-lucky person because you’re always in a good mood.

Thankfully, we’re not doing this all the time, or we would be driving ourselves crazy. Instead, there are certain people in our lives about whose judgments we worry more than others. Imagine you are working in a new job. You respect your new boss, and you want to gain their respect in return. Currently, you believe that your boss doesn’t think you’re a good fit for the organization because you are not serious enough about your job. If you perceive that your boss will like you more if you are a more serious worker, then you will alter your behavior to be more in line with what your boss sees as “serious.” In this situation, your boss didn’t come out and say that you were not a serious worker, but we perceived the boss’ perception of us and their judgment of that perception of us and altered our behavior to be seen in a better light.

Self-Esteem

One of the most commonly discussed intrapersonal communication ideas is an individual’s self-esteem, with many academic and popular press books on the topic. Self-esteem is an individual’s subjective evaluation of their abilities and limitations. Let’s break down this definition into sizeable chunks.

Subjective Evaluation

The definition states that someone’s self-esteem is an “individual’s subjective evaluation.” The word “subjective” emphasizes that self-esteem is based on an individual’s emotions and opinions and is not based on facts. For example, many people suffer from what is called the impostor syndrome, or they doubt their accomplishments, knowledge, and skills, so they live in fear of being found out a fraud. These individuals have a constant fear that people will figure out that they are “not who they say they are.” Research in this area generally shows that these fears of “being found out” are not based on any kind of fact or evidence. Instead, these individuals’ emotions and opinions of themselves are fueled by incongruent self-concepts. Types of people who suffer from imposter syndrome include physicians, CEOs, academics, celebrities, artists, and pretty much any other category. Again, it’s important to remember that these perceptions are subjective and not based on any objective sense of reality. Imagine a physician who has gone through four years of college, three years of medical school, three years of residency, and another four years of specialization training only to worry that someone will find out that they aren’t that smart after all. There’s no objective basis for this perception; it’s completely subjective and flies in the face of facts.

In addition to the word “subjective,” we also use the word “evaluation” in the definition of self-esteem. By evaluation, we mean a determination or judgment about the quality, importance, or value of something. We evaluate how we interact with others, the work we complete, and we evaluate ourselves and our specific abilities and limitations. Our lives are filled with constant evaluations.

Abilities

When we discuss our abilities, we are referring to the acquired or natural capacity for specific talents, skills, or proficiencies that facilitate achievement or accomplishment. First, someone’s abilities can be inherent (natural) or they can be learned (acquired). For example, if someone is 6’6”, has excellent reflexes, and has a good sense of space, they may find that they have a natural ability to play basketball that someone who is 4’6”, has poor reflex speed, and has no sense of space simply does not have. That’s not to say that both people cannot play basketball, but they will both have different ability levels. They can both play basketball because they can learn skills necessary to play basketball: shooting the ball, dribbling, rules of the game, etc. In a case like basketball, professional-level players need to have a combination of both natural and acquired abilities.

Limitations

In addition to one’s abilities, it’s always important to recognize that we all have limitations. A 4’6″ basketball player might be quite good at the game, but physically they will not be able to dunk the ball on a standard-height rim. We all have limitations on what we can and cannot do. When it comes to your self-esteem, it’s about how you evaluate those limitations. Do you realize your limitations and they don’t bother you? Or do your limitations prevent you from being happy with yourself? When it comes to understanding limitations, it’s important to recognize the limitations that we can change and the limitations we cannot change. One problem that many people have when it comes to limitations is that they cannot differentiate between the types of limitations.

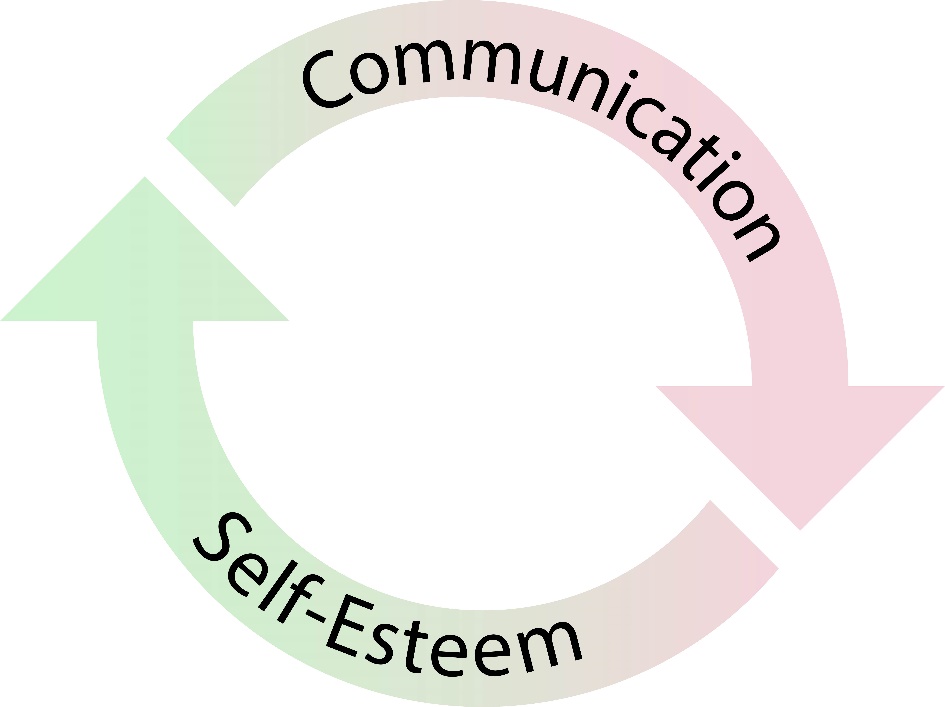

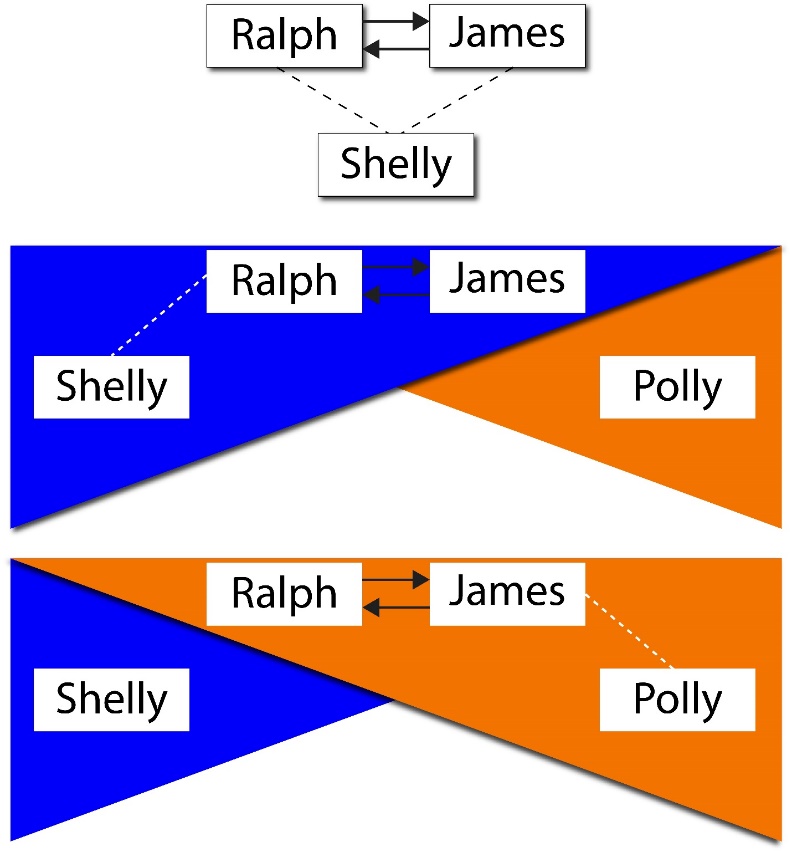

Self-Esteem and Communication

You may be wondering by this point about the importance of self-esteem in interpersonal communication. Self-esteem and communication have a reciprocal relationship (as depicted in Figure 4). Our communication with others impacts our self-esteem, and our self-esteem impacts our communication with others. As such, our self-esteem and communication are constantly being transformed by each other.

As such, interpersonal communication and self-esteem cannot be separated. Now, our interpersonal communication is not the only factor that impacts self-esteem, but interpersonal interactions are one of the most important tools we have in developing our selves.

Self-Compassion

Some researchers have argued that self–esteem as the primary measure of someone’s psychological health may not be wise because it stems from comparisons with others and judgments. As such, Kristy Neff has argued for the use of the term self-compassion.16

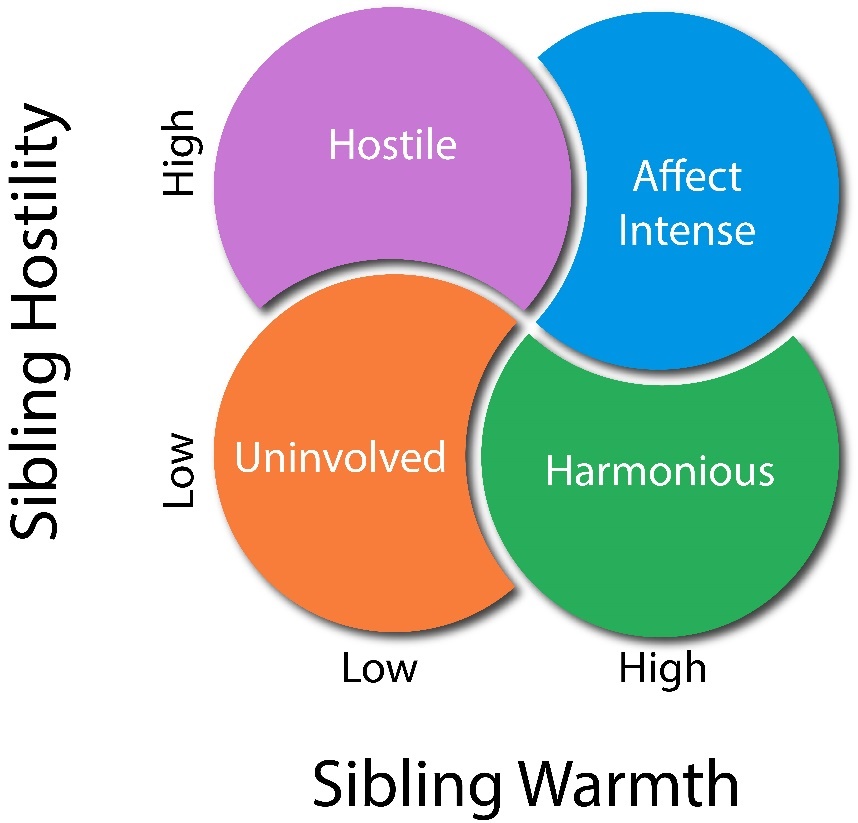

Self-Compassion stems out of the larger discussion of compassion. Compassion then is about the sympathetic consciousness for someone who is suffering or unfortunate. Self-compassion “involves being touched by and open to one’s own suffering, not avoiding or disconnecting from it, generating the desire to alleviate one’s suffering and to heal oneself with kindness. Self-compassion also involves offering nonjudgmental understanding to one’s pain, inadequacies and failures, so that one’s experience is seen as part of the larger human experience.”18 Neff argues that self-compassion can be broken down into three distinct categories: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness (Figure 5).

Self-Kindness, Common Humanity, and Mindfulness

Self-kindness is simply extending the same level of care and understanding to ourselves as we would to others. Instead of being harsh and judgmental, we are encouraging and supportive. Instead of being critical, we are empathic towards ourselves. Now, this doesn’t mean that we just ignore our faults and become narcissistic (excessive interest in oneself), but rather we realistically evaluate ourselves. Second, self-compassion is common humanity, or “seeing one’s experiences as part of the larger human experience rather than seeing them as separating and isolating.”19 No one is perfect. No one is ever going to be perfect. We all make mistakes (some big, some small). We’re also all going to experience pain and suffering in our lives. Being self-compassionate is approaching this pain and suffering and seeing it for what it is, a natural part of being human. “The pain I feel in difficult times is the same pain you feel in difficult times. The circumstances are different, the degree of pain is different, but the basic experience of human suffering is the same.”21 The final factor of self-compassion is mindfulness. Naff defines mindfulness as “holding one’s painful thoughts and feelings in balanced awareness rather than over-identifying with them.”22 Essentially, Naff argues that mindfulness is an essential part of self-compassion, because we need to be able to recognize and acknowledge when we’re suffering so we can respond with compassion to ourselves.

Don’t Feed the Vulture

One area that we know can hurt someone’s self-esteem is what Sidney Simon calls “vulture statements.” According to Simon,

Vulture (‘vul-cher) noun. 1: any of various large birds of prey that are related to the haws, eagles and falcons, but with the head usually naked of feathers and that subsist chiefly or entirely on dead flesh.23

Unfortunately, all of us have vultures circling our heads or just sitting on our shoulders. In Figure 3.5, we see a young woman feeding an apple to her vulture. This apple represents all of the negative things we say about ourselves during a day. Many of us spend our entire days just feeding our vultures and feeding our vultures these self-deprecating, negative thoughts and statements. Admittedly, these negative thoughts “come from only one place. They grow out of other people’s criticisms, from the negative responses to what we do and say, and the way we act.”24 We have the choice to either let these thoughts consume us or fight them. According to Richmond and colleagues the following are characteristic statements that vultures wait to hear so they can feed:

- Oh boy, do I look awful today; I look like I’ve been up all night.

- Oh, this is going to be an awful day.

- I’ve already messed up. I left my students’ graded exams at home.

- Boy, I should never have gotten out of bed this morning.

- Gee whiz. I did an awful job of teaching that unit.

- Why can’t I do certain things as well as Mr. Smith next door?

- Why am I always so dumb?

- I can’t believe I’m a teacher; why, I have the mentality of a worm.

- I don’t know why I ever thought I could teach.

- I can’t get anything right.

- Good grief, what am I doing here? Why didn’t I select any easy job?

- I am going nowhere, doing nothing; I am a failure at teaching.

- In fact, I am a failure in most things I attempt.25

Dealing with the Vulture

Do any of these vulture statements sound familiar to you? If you’re like us, I’m sure they do. Part of self-compassion is learning to recognize these vulture statements when they appear in our minds and evaluate them critically. Ben Martin proposes four ways to challenging vulture statements (negative self-talk):

- Reality testing

- What is my evidence for and against my thinking?

- Are my thoughts factual, or are they just my interpretations?

- Am I jumping to negative conclusions?

- How can I find out if my thoughts are actually true?

- Look for alternative explanations

- Are there any other ways that I could look at this situation?

- What else could this mean?

- If I were being positive, how would I perceive this situation?

- Putting it in perspective

- Is this situation as bad as I am making out to be?

- What is the worst thing that could happen? How likely is it?

- What is the best thing that could happen?

- What is most likely to happen?

- Is there anything good about this situation?

- Will this matter in five years?

- Using goal-directed thinking

- Is thinking this way helping me to feel good or to achieve my goals?

- What can I do that will help me solve the problem?

- Is there something I can learn from this situation, to help me do it better next time?26

So, next time those vultures start circling you, check that negative self-talk. When we can stop these patterns of negativity towards ourselves and practice self-compassion, we can start plucking the feathers of those vultures. The more we treat ourselves with self-compassion and work against those vulture statements, the smaller and smaller those vultures get. Our vultures may never die, but we can make them much, much smaller.

Personality and Perception in Intrapersonal Communication

Personality is defined as the combination of traits or qualities—such as behavior, emotional stability, and mental attributes—that make a person unique. Before we delve into personality, let’s take a quick look at two common themes in this area of research: nature or nurture and temperament.

Nature or Nurture

One of the oldest debates in the area of personality research is whether a specific behavior or thought process occurs within an individual because of their nature (genetics) or nurture (how they were raised). The first person to start investigating this phenomenon was Sir Francis Galton back in the 1870s.28 In 1875, Galton sought out twins and their families to learn more about similarities and differences. As a whole, Galton found that there were more similarities than differences: “There is no escape from the conclusion that nature prevails enormously over nurture when the differences of nurture do not exceed what is commonly to be found among persons of the same rank of society and in the same country.”29 However, the reality is that Galton’s twin participants had been raised together, so parsing out nature and nurture (despite Galton’s attempts) wasn’t completely possible. Although Galton’s anecdotes provided some interesting stories, that’s all they amounted to.

Minnesota Twins Raised Apart

So, how does one determine if something ultimately nature or nurture? The next breakthrough in this line of research started in the late 1970s when Thomas J. Bouchard and his colleagues at Minnesota State University began studying twins who were raised separately.30 This research started when a pair of twins, Jim Lewis and Jim Springer, were featured in an article on February 19, 1979, in the Lima News in Lima, Ohio.31 Jim and Jim were placed in an adoption agency and separated from each other at four weeks of age. They grew up just 40 miles away from each other, but they never knew the other one existed. Jess and Sarah Springer and Ernest and Lucille Lewis were looking to adopt, and both sets of parents were told that their Jim had been a twin, but they were also told that his twin had died. Many adoption agencies believed that placing twins with couples was difficult, so this practice of separating twins at birth was an inside practice that the adoptive parents knew nothing about. Jim Lewis’ mother had found out that Jim’s twin was still alive when he was toddler, so Jim Lewis knew that he had a twin but didn’t seek him out until he was 39 years old. Jim Springer, on the other hand, learned that he had been a twin when he was eight years old, but he believed the original narrative that his twin had died.

As you can imagine, Jim Springer was pretty shocked when he received a telephone message with his twin’s contact information out of nowhere one day. The February 19th article in the Lima News was initially supposed to be a profile piece on one of the Springers’ brothers, but the reporter covering the wedding found Lewis and Springer’s tale fascinating. The reporter found several striking similarities between the twins:32

- Their favorite subject in school was math

- Both hated spelling in school

- Their favorite vacation spot was Pas Grille Beach in Florida

- Both had previously been in law enforcement

- They both enjoyed carpentry as a hobby

- Both were married to women named Betty

- Both were divorced from women named Linda

- Both had a dog named “Toy”

- Both started suffering from tension headaches when they were 18

- Even their sons’ names were oddly similar (James Alan and James Allan)

This sensationalist story caught the attention of Bouchard because this opportunity allowed him and his colleagues to study the influence rearing had on twins in a way that wasn’t possible when studying twins who were raised together.

Over the next decade, Bouchard and his team of researchers would seek out and interview over 100 different pairs of twins or sets of triplets who had been raised apart.33 The researchers were able to compare those twins to twins who were reared together. As a whole, they found more similarities between the two twin groups than they found differences. This set of studies is one of many that have been conducted using twins over the years to help us understand the interrelationship between rearing and genetics.

Twin Research in Communication

In the field of communication, the first major twin study published was conducted by Cary Wecht Horvath in 1995.34 Horvath compared 62 pairs of identical twins and 42 pairs of fraternal twins to see if they differed in terms of their communicator style, or “the way one verbally, nonverbally, and paraverbally interacts to signal how literal meaning should be taken, filtered, or understood.”35 Identical twins’ communicator styles were more similar than those of fraternal twins. Hence, a good proportion of someone’s communicator style appears to be a result of genetic makeup. However, this is not to say that genetics was the only factor at play about one’s communicator style.

Other research in the field of communication has examined how a range of different communication variables are associated with genetics when analyzed through twin studies:36,37, 38

- Interpersonal Affiliation

- Aggressiveness

- Social Anxiety

- Audience Anxiety

- Self-Perceived Communication Competence

- Willingness to Communicate

- Communicator Adaptability

Despite similarities across many categories, it would be wrong to argue that all of our communication is biological. We cannot dismiss the importance that genetics plays in our communicative behavior and development, but social and environmental factors are just as important in shaping communication. For example, imagine we have two twins that were separated at birth. One twin is put into a middle-class family where she will be exposed to a lot of opportunities. The other twin, on the other hand, was placed with a lower-income family where the opportunities she will have in life are more limited. The first twin goes to a school that has lots of money and award-winning teachers. The second twin goes to an inner-city school where there aren’t enough textbooks for the students, and the school has problems recruiting and retaining qualified teachers. The first student has the opportunity to engage in a wide range of extracurricular activities both in school (mock UN, debate, student council, etc.) and out of school (traveling softball club, skiing, yoga, etc.). The second twin’s school doesn’t have the budget for extracurricular activities, and her family cannot afford out of school activities, so she ends up taking a job when she’s a teenager. Now imagine that these twins are naturally aggressive. The first twin’s aggressiveness may be exhibited by her need to win in both mock UN and debate; she may also strive to not only sit on the student council but be its president. In this respect, she demonstrates more prosocial forms of aggression. The second twin, on the other hand, doesn’t have these more prosocial outlets for her aggression. As such, her aggression may be demonstrated through more interpersonal problems with her family, teachers, friends, etc.… Instead of having those more positive outlets for her aggression, she may become more physically aggressive in her day-to-day life. In other words, both biological dispositions and context are very important to communicative behaviors.

Temperament Types

Temperament is the genetic predisposition that causes an individual to behave, react, and think in a specific manner. The notion that people have fundamentally different temperaments dates back to the Greek physician Hippocrates, known today as the father of medicine, who first wrote of four temperaments in 370 BCE: Sanguine, Choleric, Phlegmatic, and Melancholic. Although closely related, temperament and personality refer to two different constructs. Jan Strelau explains that temperament and personality differ in five specific ways:

- Temperament is biologically determined where personality is a product of the social environment.

- Temperamental features may be identified from early childhood, whereas personality is shaped in later periods of development.

- Individual differences in temperamental traits like anxiety, extraversion-introversion, and stimulus-seeking are also observed in animals, whereas personality is the prerogative of humans.

- Temperament stands for stylistic aspects. Personality for the content aspect of behavior.

- Unlike temperament, personality refers to the integrative function of human behavior.39

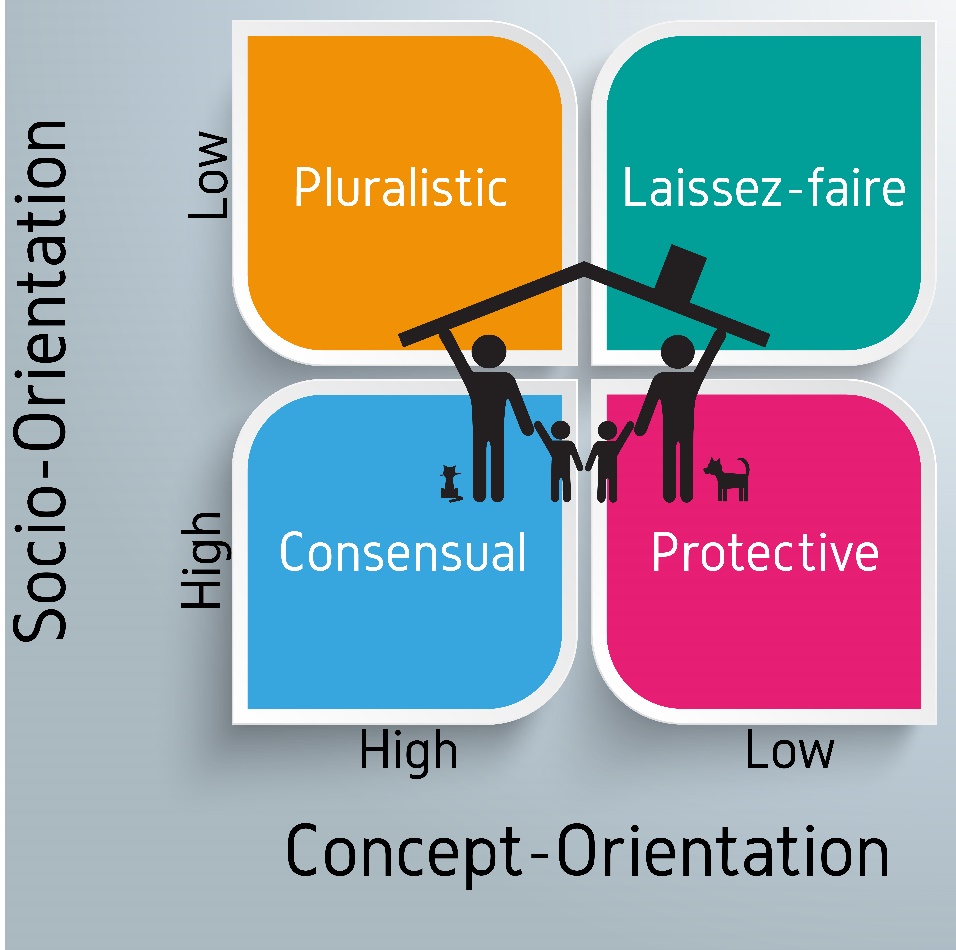

In 1978, David Keirsey developed the Keirsey Temperament Sorter, a questionnaire that combines the Myers-Briggs Temperament Indicator with a model of four temperament types developed by psychiatrist Ernst Kretschmer in the early 20th century.40 In reality, there are many four-type personality systems that have been created over the years. Table 1 provides just a number of the different four-type personality system that are available on the market today. Each one has its quirks and patterns, but the basic results are generally the same.

| System | Personalities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocrates Greek Terms | Sanguine | Melancholy | Choleric | Phlegmatic |

| Wired that Way | Popular Sanguine |

Perfect Melancholy | Powerful Choleric | Peaceful Phlegmatic |

| Keirsy Temperament (1967) | Artisan Sensation Seeking |

Rational Knowledge Seeking |

Guardian Security Seeking |

Idealist Identity Seeking |

| Carl Jung’s Theory (1921) | Feeling | Thinking | Sensing | Intuition |

| Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (1962) |

Feeler Extravert |

Thinker Introvert |

Intuiter Extravert |

Sensor Introvert |

| “What’s My Style?” (WMS) | Spirited | Systematic | Direct | Considerate |

| The P’s | Popular | Perfect | Powerful | Peaceful |

| The S’s | Spirited | Systematic | Self-propelled | Solid |

| The A’s | Active | Analytical | Administrative | Amiable |

| LEAD Test | Expressor | Analyst | Leader | Dependable |

| Biblical Characters | Peter | Moses | Paul | Abraham |

| DiSC | Influencing of Others | Cautiousness/ Compliance |

Dominance | Steadiness |

| McCarthy/4MAT System | Dynamic | Analytic | Common Sense | Innovative |

| Plato (340 BC) | Artisan | Scientist | Guardian | Philosopher |

| Enneagram | Helper Romantic |

Asserter Perfectionist |

Adventurer Achiever |

Peacemaker Observer |

| True Colors | Orange | Gold | Green | Blue |

| Children’s Literature | Tigger | Eeyore | Rabbit | Pooh |

| Charlie Brown Characters | Snoopy | Linus | Lucy | Charlie Brown |

| Who Moved My Cheese? | Scurry | Hem | Sniff | Haw |

| LEAD Test | Expresser | Analyst | Leader | Dependable |

| Eysenck’s EPQ-R | High Extravert Low Neurotic |

Low Extravert High Neurotic |

High Extravert High Neurotic |

Low Extravert Low Neurotic |

Table 1. Comparing 4-Personality Types

None of the research examining the four types has found clear sex differences among the patterns. Females and males are seen proportionately in all four categories. Keirsey argues that the consistent use of the four temperament types (whatever terms we use) is an indication of the long-standing tradition and complexity of these ideas.41

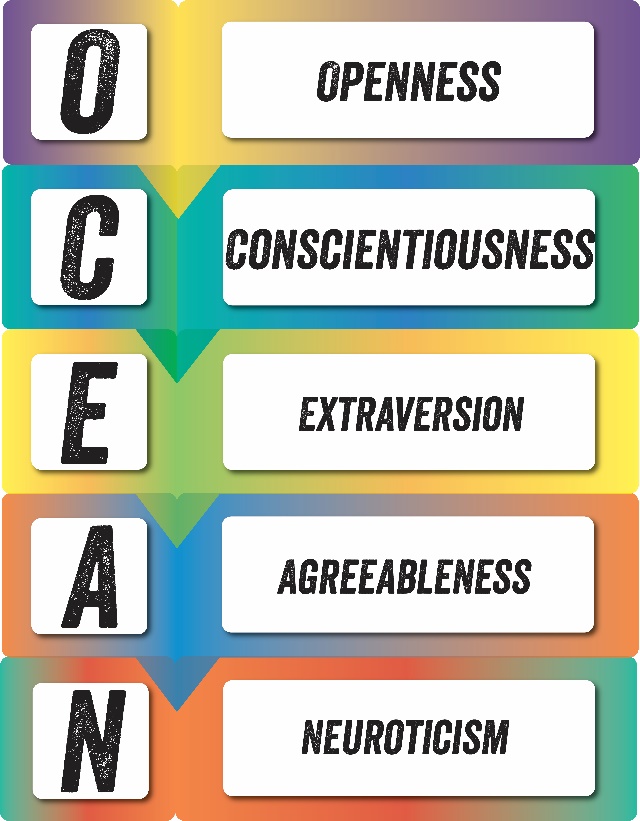

Personality and The Big Five

Unlike temperament, which has been argued to have a biological root, personality is a more flexible combination of socially derived and assessed traits held by a person. One of the most commonly discussed personality frameworks is the Big Five.42 Figure 6 shows the Big Five.

Openness

Openness refers to “openness to experience,” or the idea that some people are more welcoming of new things. These people are willing to challenge their underlying life assumptions and are more likely to be amenable to differing points of view. Table 2 explores some of the traits associated with having both high levels of openness and having low levels of openness.

| High Openness | Low Openness |

|---|---|

| Original | Conventional |

| Creative | Down to Earth |

| Complex | Narrow Interests |

| Curious | Unadventurous |

| Prefer Variety | Conforming |

| Independent | Traditional |

| Liberal | Unartistic |

Table 2. Openness

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness is the degree to which an individual is aware of their actions and how their actions impact other people. Table 3 explores some of the traits associated with having both high levels of conscientiousness and having low levels of conscientiousness.

| High Conscientiousness | Low Conscientiousness |

|---|---|

| Careful | Negligent |

| Reliable | Disorganized |

| Hard-Working | Impractical |

| Self-Disciplined | Thoughtless |

| Punctual | Playful |

| Deliberate | Quitting |

| Knowledgeable | Uncultured |

Table 3. Conscientiousness

Extraversion

Extraversion is the degree to which someone is sociable and outgoing. Table 4 explores some of the traits associated with having both high levels of extraversion and having low levels of extraversion.

| High Extraversion | Low Extraversion |

|---|---|

| Sociable | Sober |

| Fun Loving | Reserved |

| Friendly | Quiet |

| Talkative | Unfeeling |

| Warm | Lonely |

| Person-Oriented | Task-Oriented |

| Dominant | Timid |

Table 4. Extraversion

Agreeableness

Agreeableness is the degree to which someone engages in prosocial behaviors like altruism, cooperation, and compassion. Table 5 explores some of the traits associated with having both high levels of agreeableness and having low levels of agreeableness.

| High Agreeableness | Low Agreeableness |

|---|---|

| Good-Natured | Irritable |

| Soft Hearted | Selfish |

| Sympathetic | Suspicious |

| Forgiving | Critical |

| Open-Minded | Disagreeable |

| Flexible | Cynical |

| Humble | Manipulative |

Table 5. Agreeableness

Neuroticism

Neuroticism is the degree to which an individual is vulnerable to anxiety, depression, and emotional instability. Table 6 explores some of the traits associated with having both high levels of neuroticism and having low levels of neuroticism.

| High Neuroticism | Low Neuroticism |

|---|---|

| Nervous | Calm |

| High-Strung | Unemotional |

| Impatient | Secure |

| Envious/Jealous | Comfortable |

| Self-Conscious | Not impulse ridden |

| Temperamental | Hardy |

| Subjective | Relaxed |

Table 6. Neuroticism

Social, Personal, and Relational Dispositions

Social-personal dispositions refer to general patterns of mental processes that impact how people socially relate to others or view themselves. Communication dispositions impact how people interact with others, some are more personal and cognitive others have greater impact on how we interact with others. 63 As you read here, if you feel like you’re facing a challenge to your social-personal mental wellbeing, we encourage you to visit https://coms-idea.ku.edu/find-support to locate resources on our campus (or seek resources on your campus if you are not at KU).

Loneliness

Loneliness is an individual’s emotional distress that results from a feeling of solitude or isolation from social relationships. Loneliness can generally be discussed as existing in one of two forms: emotional and social. Emotional loneliness results when an individual feels that he or she does not have an emotional connection with others. We generally get these emotional connections through our associations with loved ones and close friends. If an individual is estranged from their family or doesn’t have close friendships, then he or she may feel loneliness as a result of a lack of these emotional relationships. Social loneliness, on the other hand, results from a lack of a satisfying social network. Imagine you’re someone who has historically been very social. Still, you move to a new city and find building new social relationships very difficult because the people in the new location are very cliquey. The inability to develop a new social network can lead someone to feelings of loneliness because he or she may feel a sense of social boredom or marginalization.

Loneliness tends to impact people in several different ways interpersonally. Some of the general research findings associated with loneliness have demonstrated that these people have lower self-esteem, are more socially passive, are more sensitive to rejection from others, and are often less socially skilled. Interestingly, lonely individuals tend to think of their interpersonal failures using an internal locus of control and their interpersonal successes externally.64

Depression

Depression is a psychological disorder characterized by varying degrees of disappointment, guilt, hopelessness, loneliness, sadness, and self-doubt, all of which negatively impact a person’s general mental and physical wellbeing. Depression (and all of its characteristics) is very difficult to encapsulate in a single definition. If you’ve ever experienced a major depressive episode, it’s a lot easier to understand what depression is compared to those who have never experienced one. Depressed people tend to be less satisfied with life and less satisfied with their interpersonal interactions as well. Research has shown that depression negatively impacts all forms of interpersonal relationships: dating, friends, families, work, etc. We will periodically come back to depression as we explore various parts of interpersonal communication.

Narcissism

Ovid’s story of Narcissus and Echo has been passed down through the ages. The story starts with a Mountain Nymph named Echo who falls in love with a human named Narcissus. When Echo reveals herself to Narcissus, he rejects her. In true Roman fashion, this slight could not be left unpunished. Echo eventually leads Narcissus to a pool of water where he quickly falls in love with his reflection. He ultimately dies, staring at himself, because he realizes that his love will never be met.

The modern conceptualization of narcissism is based on Ovid’s story of Narcissus. Today researchers view narcissism as a psychological condition (or personality disorder) in which a person has a preoccupation with one’s self, an inflated sense of one’s importance, and longing of admiration from others. Highly narcissistic individuals are completely self-focused and tend to ignore the communicative needs and emotions of others. In fact, in social situations, highly narcissistic individuals strive to be the center of attention.

Vangelisti and colleagues examined a purely communicative form of narcissism they deemed conversational narcissism.65 Conversational narcissism is an extreme focusing of one’s interests and desires during an interpersonal interaction while completely ignoring the interests and desires of another person: Vangelisti et al. found several attributes of conversationally narcissistic behavior. Conversational narcissists inflate their self-importance via bragging, refusing to listen to criticism, praising one’s self, etc. They may talk so fast others cannot interject, shift the topic to their self, interrupting others, etc. Conversational narcissists often attempt to show-off or entertain others to turn the focus on themselves. Some behaviors include primping or preening, dressing to attract attention, being or laughing louder than others, positioning one’s self in the center, etc. Lastly, conversational narcissists tend to have impersonal relationships. During their interactions with others, conversational narcissists show a lack of caring about another person and a lack of interest in another person. Some common behaviors include “glazing over” while someone else is speaking, looking impatient while someone is speaking, looking around the room while someone is speaking, etc. As you can imagine, people engaged in interpersonal encounters with conversational narcissists are generally highly unsatisfied with those interactions.

Empathy

Empathy is the ability to recognize and mutually experience another person’s attitudes, emotions, experiences, and thoughts. Highly empathic individuals have the unique ability to connect with others interpersonally, because they can truly see how the other person is viewing life. Individuals who are unempathetic generally have a hard time taking or seeing another person’s perspective, so their interpersonal interactions tend to be more rigid and less emotionally driven. Generally speaking, people who have high levels of empathy tend to have more successful and rewarding interactions with others when compared to unempathetic individuals. Furthermore, people who are interacting with a highly empathetic person tend to find those interactions more satisfying than when interacting with someone who is unempathetic.

Self-Monitoring

The last of the personal-social dispositions is referred to as self-monitoring. In 1974 Mark Snyder developed his basic theory of self-monitoring, which proposes that individuals differ in the degree to which they can control their behaviors following the appropriate social rules and norms involved in interpersonal interaction.67 In this theory, Snyder proposes that there are some individuals adept at selecting appropriate behavior in light of the context of a situation, which he deems high self-monitors. High self-monitors want others to view them in a precise manner (impression management), so they enact communicative behaviors that ensure suitable or favorable public appearances. On the other hand, some people are merely unconcerned with how others view them and will act consistently across differing communicative contexts despite the changes in cultural rules and norms. Snyder called these people low self-monitors.

Interpersonally, high self-monitors tend to have more meaningful and satisfying interpersonal interactions with others. Conversely, individuals who are low self-monitors tend to have more problematic and less satisfying interpersonal relationships with others. In romantic relationships, high self-monitors tend to develop relational intimacy much faster than individuals who are low self-monitors. Furthermore, high self-monitors tend to build lots of interpersonal friendships with a broad range of people. Low-self-monitors may only have a small handful of friends, but these friendships tend to have more depth. Furthermore, high self-monitors are also more likely to take on leadership positions and get promoted in an organization when compared to their low self-monitoring counterparts. Overall, self-monitoring is an important dispositional characteristic that impacts interpersonal relationships.

Argumentativeness/Verbal Aggressiveness

Starting in the mid-1980s, Dominic Infante and Charles Wigley defined verbal aggression as “the tendency to attack the self-concept of individuals instead of, or in addition to, their positions on topics of communication.”80 Notice that this definition specifically is focused on the attacking of someone’s self-concept or an individual’s attitudes, opinions, and cognitions about one’s competence, character, strengths, and weaknesses. For example, if someone perceives themself as a good worker, then a verbally aggressive attack would demean that person’s quality of work or their ability to do future quality work. In a study conducted by Terry Kinney,81 he found that self-concept attacks happen on three basic fronts: group membership (e.g., “Your whole division is a bunch of idiots!”), personal failings (e.g., “No wonder you keep getting passed up for a promotion!”), and relational failings (e.g., “No wonder your spouse left you!”).

Now that we’ve discussed what verbal aggression is, we should delineate verbal aggression from another closely related term, argumentativeness. According to Dominic Infante and Andrew Rancer, argumentativeness is a communication trait that “predisposes the individual in communication situations to advocate positions on controversial issues, and to attacking verbally the positions which other people take on these issues.”82 You’ll notice that argumentativeness occurs when an individual attacks another’s positions on various issues; whereas, verbal aggression occurs when an individual attacks someone’s self-concept instead of attack another’s positions. Argumentativeness is seen as a constructive communication trait, while verbal aggression is a destructive communication trait.

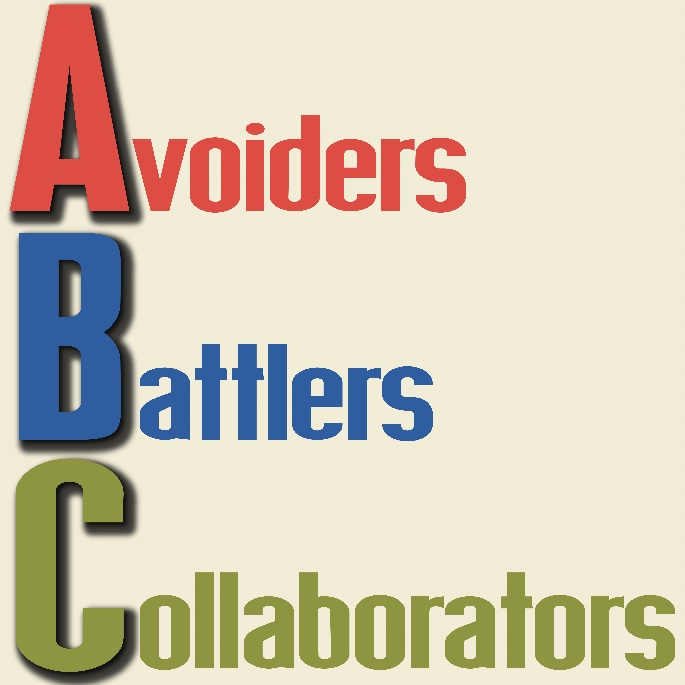

Individuals who are highly verbally aggressive are not liked by those around them.83 Researchers have seen this pattern of results across different relationship types. Highly verbally aggressive individuals tend to justify their verbal aggression in interpersonal relationships regardless of the relational stage (new vs. long-term relationship).84 In an interesting study conducted by Beth Semic and Daniel Canary, the two set out to watch interpersonal interactions and the types of arguments formed during those interactions based on individuals’ verbal aggressiveness and argumentativeness.85 The researchers had friendship-dyads come into the lab and were asked to talk about two different topics. The researchers found that highly argumentative individuals did not differ in the number of arguments they made when compared to their low argumentative counterparts. However, highly verbally aggressive individuals provided far fewer arguments when compared to their less verbally aggressive counterparts. Although this study did not find that highly argumentative people provided more (or better) arguments, highly verbally aggressive people provided fewer actual arguments when they disagreed with another person. Overall, verbal aggression and argumentativeness have been shown to impact several different interpersonal relationships, so we will periodically revisit these concepts throughout the book.

Attachment

In a set of three different volumes, John Bowlby theorized that humans were born with a set of inherent behaviors designed to allow proximity with supportive others.95 These behaviors were called attachment behaviors, and the supportive others were called attachment figures. Inherent in Bowlby’s model of attachment is that humans have a biological drive to attach themselves with others. For example, a baby’s crying and searching help the baby find their attachment figure (typically a parent/guardian) who can provide care, protection, and support. Infants (and adults) view attachment as an issue of whether an attachment figure is nearby, accessible, and attentive? Bowlby believed that these interpersonal models, which were developed in infancy through thousands of interactions with an attachment figure, would influence an individual’s interpersonal relationships across their entire life span. According to Bowlby, the basic internal working model of affection consists of three components.96 Infants who bond with their attachment figure during the first two years develop a model that people are trustworthy, develop a model that informs the infant that he or she is valuable, and develop a model that informs the infant that he or she is effective during interpersonal interactions. As you can easily see, not developing this model during infancy leads to several problems.

If there is a breakdown in an individual’s relationship with their attachment figure (primarily one’s mother), then the infant would suffer long-term negative consequences. Bowlby called his ideas on the importance of mother-child attachment and the lack thereof as the Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis. Bowlby hypothesized that maternal deprivation occurred as a result of separation from or loss of one’s mother or a mother’s inability to develop an attachment with her infant. This attachment is crucial during the first two years of a child’s life. Bowlby predicted that children who were deprived of attachment (or had a sporadic attachment) would later exhibit delinquency, reduced intelligence, increased aggression, depression, and affectionless psychopathy – the inability to show affection or care about others.

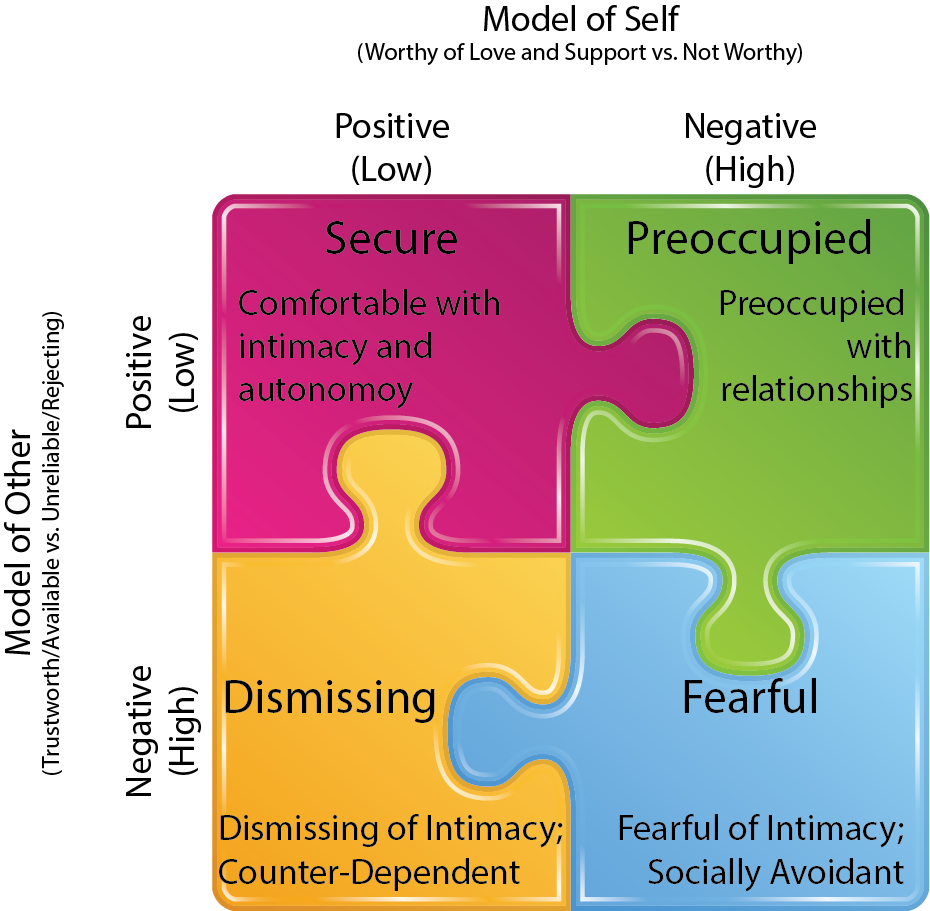

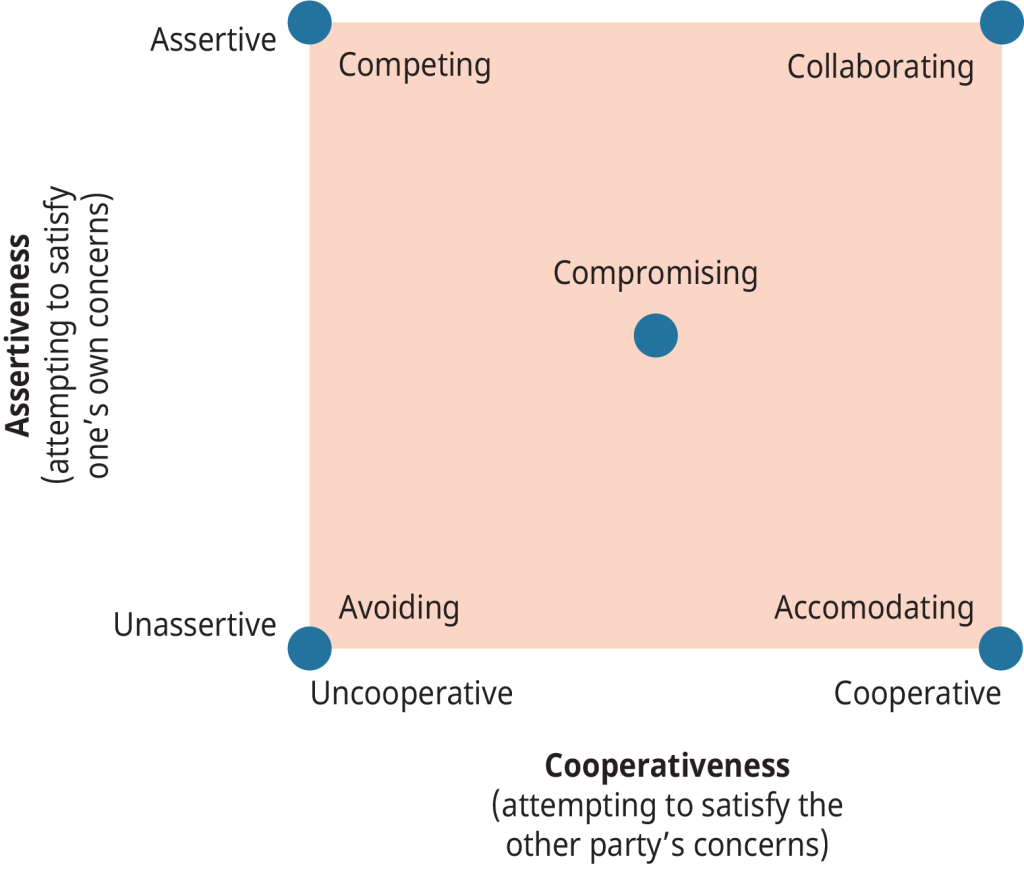

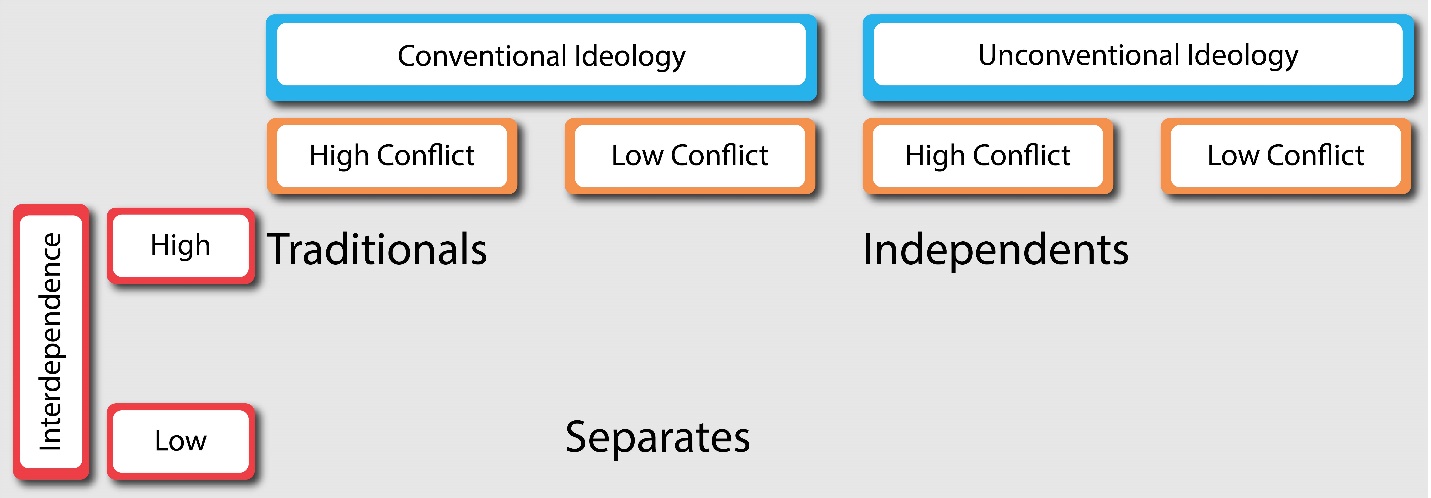

In 1991, Kim Bartholomew and Leonard Horowitz expanded on Bowlby’s work developing a scheme for understanding adult attachment.97 In this study, Bartholomew and Horowitz proposed a model for understanding adult attachment. On one end of the spectrum, you have an individual’s abstract image of themself as being either worthy of love and support or not. On the other end of the spectrum, you have an individual’s perception of whether or not another person will be trustworthy/available or another person is unreliable and rejecting. When you combine these dichotomies, you end up with four distinct attachment styles (as seen in Figure 7).

The first attachment style is labeled secure, because these individuals believe that they are loveable and expect that others will generally behave in accepting and responsive ways within interpersonal interactions. Not surprisingly, secure individuals tend to show the most satisfaction, commitment, and trust in their relationships. The second attachment style, preoccupied, occurs when someone does not perceive themself as worthy of love but does generally see people as trustworthy and available for interpersonal relationships. These individuals would attempt to get others to accept them. The third attachment style, fearful (sometimes referred to as fearful avoidants),98 represents individuals who see themselves as unworthy of love and generally believe that others will react negatively through either deception or rejection. These individuals simply avoid interpersonal relationships to avoid being rejected by others. Even in communication, fearful people may avoid communication because they simply believe that others will not provide helpful information or others will simply reject their communicative attempts. The final attachment style, dismissing, reflects those individuals who see themselves as worthy of love, but generally believes that others will be deceptive and reject them in interpersonal relationships. These people tend to avoid interpersonal relationships to protect themselves against disappointment that occurs from placing too much trust in another person or making one’s self vulnerable to rejection.

Key Takeaways

- Perception involves attending, organizing, and interpreting.

- Our sense of self including self-image, self-worth, and ideal self are manifestations of what we think of ourselves and how we think others see us (the looking glass self)

- Personality and temperament have many overlapping characteristics, but the basis of them is fundamentally different. Personality is the product of one’s social environment and is generally developed later in one’s life. Temperament, on the other hand, is one’s innate genetic predisposition that causes an individual to behave, react, and think in a specific manner, and it can easily be seen in infants.

- The Big Five or OCEAN model describes common personality traits.

- Social, personal, and relational dispositions affect how we communicate with others.

Key Terms

affectionless psychopathy

The inability to show affection or care about others.

argumentativeness

Communication trait that predisposes the individual in communication situations to advocate positions on controversial issues, and to attack verbally the positions which other people take on these issues.

communication apprehension

The fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons.

communication dispositions

General patterns of communicative behavior.

dismissing attachment

Attachment style posed by Kim Bartholomew and Leonard Horowitz describing individuals who see themselves as worthy of love, but generally believe that others will be deceptive and reject them in interpersonal relationships.

depression

A psychological disorder characterized by varying degrees of disappointment, guilt, hopelessness, loneliness, sadness, self-doubt, all of which negatively impact a person’s general mental and physical wellbeing.

emotional loneliness

Form of loneliness that occurs when an individual feels that he or she does not have an emotional connection with others.

empathy

The ability to recognize and mutually experience another person’s attitudes, emotions, experiences, and thoughts.

extraversion

An individual’s likelihood to be talkative, dynamic, and outgoing.

fearful attachment

Attachment style posed by Kim Bartholomew and Leonard Horowitz describing individuals who see themselves as unworthy of love and generally believe that others will react negatively through either deception or rejection.

ideal-self

The version of yourself that you would like to be, which is created through our life experiences, cultural demands, and expectations of others.

intrapersonal

Something that exists or occurs within an individual’s self or mind.

intrapersonal communication

Communication phenomena that exist within or occurs because of an individual’s self or mind.

introversion

An individual’s likelihood to be quiet, shy, and more reserved.

locus of control

An individual’s perceived control over their behavior and life circumstances.

loneliness

An individual’s emotional distress that results from a feeling of solitude or isolation from social relationships.

Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis

Hypothesis posed by John Bowby that predicts that infants who are denied maternal attachment will experience problematic outcomes later in life.

narcissism

A psychological condition (or personality disorder) in which a person has a preoccupation with one’s self.

personality

The combination of traits or qualities such as behavior, emotional stability, and mental attributes that make a person unique.

preoccupied attachment

Attachment style posed by Kim Bartholomew and Leonard Horowitz describing individuals who do not perceive themselves as worthy of love, but do generally see people as trustworthy and available for interpersonal relationships.

responsiveness

The degree to which an individual considers other’s feelings, listens to what others have to say, and recognizes the needs of others during interpersonal interactions.

secure attachment

Attachment style posed by Kim Bartholomew and Leonard Horowitz describing individuals who believe that they are lovable and expect that others will generally behave in accepting and responsive ways within interpersonal interactions.

self-concept

An individual’s belief about themself, including the person’s attributes and who and what the self is.

self-conscious shyness

Feeling conspicuous or socially exposed when dealing with others face-to-face.

self-esteem

An individual’s subjective evaluation of their abilities and limitations.

self-image

The view an individual has of themself.

self-monitoring

The theory that individuals differ in the degree to which they can control their behaviors in accordance with the appropriate social rules and norms involved in interpersonal interaction.

self-worth

The degree to which you see yourself as a good person who deserves to be valued and respected.

social loneliness

Form of loneliness that occurs from a lack of a satisfying social network.

social-personal dispositions

General patterns of mental processes that impact how people socially relate to others or view themselves.

temperament

The genetic predisposition that causes an individual to behave, react, and think in a specific manner.

verbal aggression

The tendency to attack the self-concept of individuals instead of, or in addition to, their positions on topics of communication.

willingness to communicate

An individual’s tendency to initiate communicative interactions with other people.

Notes

Something that exists or occurs within an individual’s self or mind.

The process of acquiring, interpreting, and organizing information that comes in through your five senses.

The act of focusing on specific objects or stimuli in the world around you

Due to our limited cognitive abilities we are always focusing on a particular things and ignoring other things

Organizing is making sense of the stimuli or assigning meaning to it.

Interpretation is the act of assigning meaning to a stimulus and then determining the worth of the object (evaluation).

The tendency to explain another individual’s behavior in relation to the individual’s internal tendencies rather than an external factor.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the importance of research

- Explain different information types

- Introduce lateral reading as a research tool and technique

- Describe types of plagiarism and explain best practices in citation

What does the word “research” conjure up for you? Do you think about sitting in a library and sorting through books or searching online? Do you picture a particular type of person?

While these images aren’t incorrect (of course libraries are connected with research), “research” can feel like an intimidating process. When does it begin? Where does it happen? When does it stop?

It’s helpful to understand what research is – the process of discovering new knowledge and investigating a topic from different points of view. Research is a process; it’s an ongoing dialogue with information. But, as you know, not all information is neutral, and not all information is ethical. Part of the research process, then, is evaluating information to determine what knowledge is ethical and best suited for your argument.

This chapter will focus on the research process and the development of critical thinking skills—or decision-making based on evaluating and critiquing information— to identify, sort, and evaluate (mostly) scholarly information. To begin, we outline why research matters, followed by insights about locating information, evaluating information, and avoiding plagiarism.

Why Research?

Research gets a bad rap. It can feel like a boring, tedious, and overwhelming process. In our current information age, we are guilty of conducting a quick search, finding what we want to read, and moving on. Many of us rarely sit down, allocate time, and commit to digging deep and researching different perspectives about an idea or argument.

But we should.

When conducting research, you get to ask questions and actually find answers. If you have ever wondered what the best strategies are when being interviewed for a job, research will tell you. If you’ve ever wondered what it takes to be a NASCAR driver, an astronaut, a marine biologist, or a university professor, once again, research is one of the easiest ways to find answers to questions you’re interested in knowing.

Research can also open a world you never knew existed. We often find ideas we had never considered and learn facts we never knew when we go through the research process. Maybe you want to learn how to compose music, draw, learn a foreign language, or write a screenplay; research is always the best step toward learning anything.

As public speakers, research will increase your confidence and competence. The more you know, the more you know. The more you research, the more precise your argument, and the clearer the depth of the information becomes.

Where to Start

Because you’ve done exploratory research (as discussed in Chapter 3), you will likely have basic, foundational information about your argument. With that basic information in mind, ask: “what question am I answering? What should I be looking for? What do I need?”

Your specific purpose statement or a working thesis are good places to start. Remember the college textbook affordability example from Chapter 3? To refresh, the specific purpose is: “to persuade my audience to support campus solutions to rising textbook costs.” Research can help zero in on a working thesis by a) finding support for our perspective and b) identifying any specific campus solution that we could advocate for.

When we begin researching, we have three initial questions that arise from our specific purpose: has the cost of college textbooks increased over time? What are the causes? And what are the opportunities to address rising textbook costs in a way that can improve access relatively quickly at your institution?

These are just our starting questions. It’s likely that we’ll revise and research for information as we learn more. As Howard and Taggart point out in their book Research Matters, research is not just a one-and-done task (2010). As you develop your speech, you may realize that you want to address a question or issue that didn’t occur to you during your first round of research, or that you’re missing a key piece of information to support one of your points.

Use these questions, prior experience, and insight from exploratory brainstorming to determine what to search and where to start. If you still feel overwhelmed, that’s OK. Start somewhere (or ask a librarian for help), and use the insights below about information types as a guide.

Locating Effective Research

Once you have a general idea about the basic needs you have for your research, it’s time to start tracking information down. Thankfully, we live in a world that is swimming with information.

As you search, you will naturally be drawn to tools and information types that are already familiar to you. Like most people, you will likely use Google as your first search strategy. As you know, Google isn’t a source, per se: it’s a search engine. It’s the vehicle that, through search terms and savvy wording, will direct you to sources related to those terms.

What information types would you expect to see in your Google search results? We are guessing your list would include: news, blogs, Wikipedia, dictionaries, and social media.

While Google is a great tool, all informational roads don’t lead to Google. Learning about different information types and different ways to access information can expand your search portfolio.

Information Types

As you begin looking for research, an array of information types will be at your disposal.

When you access a piece of information, you should determine what you are looking at. Is it a blog? an online academic journal? an online newspaper? a website for an organization? Will these information types be useful in answering the questions that you’ve identified?

Common helpful information types include websites, scholarly articles, books, and government reports, to name a few. To determine the usefulness of an information type, you should familiarize yourself with what those sources are and their goals.

Information types are often categorized as either academic or nonacademic.

Nonacademic information sources are sometimes also called popular press information sources; their primary purpose is to be read by the general public. Most nonacademic information sources are written at a sixth to eighth-grade reading level, so they are very accessible. Although the information often contained in these sources can be limited, the advantage of using nonacademic sources is that they appeal to a broad, general audience.

Alternatively, academic sources are often (not always) peer-reviewed by like-minded scholars in the field. Academic publications can take longer to publish because academics have established a series of checklists that are required to determine the credibility of the information. Because of this process, it takes a while! That delay can result in nonacademic sources providing information before scholarly academics have tested or studied the phenomena.

In addition, be cognizant of who produces information and who that information is produced for. Table 4.1 simplistically illustrates the producer and audience of our short list of information types.

|

Information Type |

What does it do? |

Who is it produced by? |

Who is it produced for? |

|

News Report |

Inform readers about what’s happening in the world. |

General Public / Journalist |

General Public |

|

Social Media |

Connects individuals, groups, and consumers |

General Public |

General Public |

|

Peer Reviewed Scholarly Journal Article |

Provides insight into an academic discipline |

Academic Researchers/Scholars |

Academic Researchers/Scholar/ Students |

|

Academic Books |

Provides insight into an academic discipline |

Academic researchers/Scholars |

Academic Researchers/Scholars /Students |

|

Government reports |

Shares information on behalf of a government agency |

Government Agencies |

Policy/Decision Makers |

|