Dark Sides of Interpersonal Communication

Interpersonal communication often results in positive outcomes, but may also lead to hurt, conflict, psychological damage, and/or relationship termination. The dark side of interpersonal communication generally refers to communication that includes negative behaviors and results in negative outcomes. Some types of communication that are considered to be on the “dark side” are: hurtful messaging, deception, infidelity, jealousy, bullying, and violence, to name a few. For many years, communication scholars failed to focus on the more negative aspects of communication, but in doing so, overlooked opportunities to create solutions for those in relationships featuring them. Awareness of these negative communication strategies may be the first step in preventing these strategies.

Learning Objectives

- Identify various hurtful messages and reactions to them.

- Define the types of, and motives for, deception in relationships.

- Identify factors leading to infidelity in real life and online.

- Understand the nature of jealousy and its inherent paradoxes.

- Acknowledge different kinds of bullying and its consequences.

- Recognize the variety and severity of domestic violence in the United States.

Hurtful Messages

“Even in the closest, most satisfying relationships, people sometimes say things that hurt each other.”1 We have all been in the position of having our feelings hurt or hurting the feelings of others. When feelings are hurt, individuals respond in many different ways. Though hurtful messages have always existed, it was not until 1994 that Anita L. Vangelisti developed a hurtful message typology and explored reactions to them. 2

Types of Hurtful Messages

Evaluations

Evaluations are messages that assess value or worth. When these messages comprise evaluations or negative assessments, the target individual may be hurt. Your passenger earnestly concluding, “You are the worst driver ever” may harm your esteem and hurt your feelings.

Accusations

The second type of hurtful message is an accusation. Accusations are assignments of fault or blame. Any number of topics can be addressed in accusations. A common source of conflict in relationships is money. An example of an accusation that might arise in conflict over money is “You are the reason this family is in constant financial turmoil.”

Directives

Directives involve a negative order or command. In everyday interaction, examples might include, “leave me alone,” or “don’t ever call me that.” “Go to hell” is a more extreme example.

Informative Statements

In the context of hurtful messages, informative statements reveal unwanted information. A supervisor might reveal the following to an employee: “I only hired you because the owner made me.” Siblings might reveal “I never wanted a younger sister” or “When Mother was dying, she told me I was her favorite.” Friends might say something like, “When you got a job at the same place as me, I felt smothered.” Informative messages reveal information that could easily be kept a secret, but are intended to hurt.

Statements of Desire

Statements of desire harmfully express an individual preference. A romantic partner might state, “the night I met you, I was more interested in your friend and really wanted to go out with him.” A friend might say, “Callie has always been a better friend than you.”

Advising Statements

Advising statements call for a course of action such as “you need to get yourself some help.” Imagine a friend complaining about going on many interviews and not getting hired and you say, “There are courses that offer interview training you could take.” The statement might hurt your friend who was only seeking comfort and not advice that indicated she had poor interview skills.

Questions

Questions are asked in a way that implies something negative. A very direct hurtful question is, “What is wrong with you?” Another subtler question that might be perceived as hurtful is, “You’ve been at the bank for ten years. Have you really not been promoted yet?”

Threats

Threats are messages that indicate a desire or the potential to inflict physical or psychological harm. A romantic partner might say, “if you go out with your friends tonight, we are through for good.” A direct physical threat might be, “I’m going to knock the stuffing out of you if you don’t get out of my way.”

Jokes

Jokes are hurtful messages that involve a prank or witticism. A coworker could disparage a supervisor’s relationship with a subordinate, “I can see who’s really in charge here.” The Breakfast Club includes a perfect example of a prank carried too far when the jock character, Andrew, explains that he and his wrestling buddies duct-taped together the butt cheeks of a nerd. It was meant to be funny, but results in physical injury to the nerd. Jokes that embarrass or cause physical harm often create emotional pain for the recipient.

Lies

Lies are deceptive speech acts that result in hurt for the recipient. Allard dishonestly tells Marta that he was at work when she tried to call him and she later finds out that he was actually out drinking with a group of women from work. Lies, when discovered, may result in feelings of being disrespected or betrayal.

Reactions to Hurtful Messages

Anita Vangelisti and Linda Crumley investigated the reactions individuals have to hurtful messages and revealed three broad categories.3

Active verbal responses involve attacking the other, defending yourself, or asking for an explanation. “Nothing is wrong with me. What’s wrong with you?” or “Why do you think there is something wrong with me?”

Acquiescent responses involve crying, conceding, or apologizing. An example is “I am so sorry. Is there something I can do to change your mind? I don’t want to lose you.”

Finally, hurtful messages can inspire invulnerable responses that range from ignoring the message to laughing. They are akin to “sticks and stones may hurt my bones, but words will never hurt me.”

Key Takeaways

- In 1994, Anita L. Vangelisti developed a hurtful message typology and explored reactions to them.

- Ten kinds of hurtful messages were identified, including accusations, threats, and jokes.

- Reactions to hurtful messages include acquiescent, active, and invulnerable responses.

Exercises

- Remember or create a joke that would serve as a hurtful message and one that would not. What is the key diference?

- On a scale of “active” to “passive,” rank the acquiescent, active, and invulnerable responses to hurtful messages and explain how you determined the ranking order.

Deception

Lies are such a prevalent and consequential type of hurtful message that they are the essence of another fully examined Dark Side behavior: deceptive communication. We are taught from a young age that we should not lie, but we often witness others engaging in socially acceptable, or “little white,” lies. As communication scholars, we must distinguish between a lie that is told for the benefit of the receiver and a lie that is told with more malicious intent.

Judee Burgoon and David Buller define deception as, ‘‘a deliberate act perpetuated by a sender to engender in a receiver beliefs contrary to what the sender believes is true.”4 H. Dan O’Hair and Michael Cody characterize deception as often purposeful, goal-directed, and used as a relational control device.5 We will begin our discussion of deception by exploring three types.

Types of Deception

Three types of deception are discussed in the field of communication: falsification, concealment, and equivocation.6 Falsification is deliberately presenting information that is not true, or fraudulent, as factual. For example, President Bill Clinton once publicly said of his intern, Monica Lewinsky, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman,” even though he eventually admitted that he did. Falsification is recognized as the most common form of deception.

Concealment is deception that involves withholding, rather than fabricating, of information. For example, if Simone asks her mother whether she can go to a concert with her teen friends, Luna and Sofia, without mentioning that two college boys will be taking them, she is engaging in concealment.

The third form of deception, equivocation, is use of a statement that could be interpreted as having more than one meaning, for the sake of obscuring the whole truth. For example, if you ask your romantic partner whether she talked to her ex-boyfriend last night, and she says, “no, I didn’t talk to him,” but she did text with him, then she is equivocating.

Lies in Romantic Relationships

Jennifer Guthrie and Adrianne Kunkel, an alumnus of the University of Kansas’ Department of Communication Studies and her advisor, asked 67 college students to record their deceptive communication in diaries for seven days and coded it into their own deception typology. The 67 students produced 327 deceptive acts, or an average of five each per week: 147 lies, 61 exaggerations, 56 half-truths, 35 diversionary responses, 26 secrets, and two undetailed uses of deception.7

Moreover, the students explained their 327 reported deceptions with 334 reasons, which Guthrie and Kunkel coded into five overarching motives for lying. Deception was used to engage in relational maintenance or to “keep the peace” when a girlfriend was told that her outfit was flattering eve though it wasn’t and when she did not mention to her boyfriend that her -ex was at a party she attended. The other four motives, managing face needs, negotiating dialectical tensions, establishing relational control, and continuing previous deception,7 are also portrayed in Table 1.

| Overarching Motives | Individual Reasons |

|---|---|

| Managing Face Needs | Supporting Positive Face |

| Protecting partner’s feelings and self-presentation | |

| Supporting Negative Face | |

| Avoiding unwanted activities and=or imposition) | |

| Negotiating Dialectical Tensions | Negotiating Autonomy/Connection |

| Balancing the need for independence versus the need for togetherness | |

| Negotiating Openness/Closedness | |

| Balancing the need for open communication versus the need for privacy | |

| Negotiating Novelty/Predictability | |

| Balancing the need for spontaneity versus the need for routine or expected behaviors | |

| Establishing Relational Control | Acting Coercive |

| Ensuring that a partner behaves or feels how the other wants them to | |

| Continuing Previous Deception | Participants indicated that they had lied about something in the past and the particular act of deception was a way of continuing or maintaining the lie |

| Relational Maintenance | Deception employed to “keep the peace,” or avoid fights and relational damage |

Table 1. Romantic Deception Motives.

Perhaps Guthrie and Kunkel’s most important finding is the extent to which participants were able to identify what they believed to be morally acceptable rationales for their acts of romantic deception.7

Key Takeaways

- Deception is a willful act designed to convey falsehoods as true.

- One typology of deceptive acts recognizes falsification, concealment, and equivocation.

- Jennifer Guthrie and Adrianne Kunkel discovered that students can identify at least five reasons for why they deceive romantic partners: relational maintenance, managing face needs, negotiating dialectical tensions, establishing relational control, and continuing previous deception.

Exercises

- Can you name a time when you, or someone else felt “trapped in a lie” and needed to continue telling it?

- Would you rather a friend deceived you with falsification, concealment, or equivocation? Why?

Infidelity

Deception is almost always involved in the performance of relational infidelity. Infidelity refers to behaviors of “cheating,” or being unfaithful to a committed spouse or other sexual partner. When extramarital sex occurs, it is called adultery. Some believe that as long as there is no sexual intercourse, there has been no infidelity. Others draw lines around particular other acts of affectionate expression such as sexual acts besides intercourse, kissing, or even holding hands. Apart from sexual or physical infidelity that involves sexual intimacy and physical involvement, there is also emotional infidelity.

Sexual infidelity might include a married person’s hookup with a person employed in a different region at their company’s convention. Emotional infidelity could include a long thread of emails between a corporate trainer and a former trainee that goes deep into problems with their individual relationships and expressions of fondness and gratitude for each other.

Infidelity can cause great feelings of guilt, shame, and fear of being caught for the cheater. It can cause feelings of inadequacy, betrayal, jealousy (see below), and anger for the partner that has been cheated on. As trust may be damaged or destroyed with the revelation of infidelity, relationships may be negatively or severely harmed, perhaps even doomed.

A variety of studies have spoken to the prevalence of infidelity, indicating that more than a quarter of married heterosexual men and women will engage in it. Researchers reported that sexual infidelity occurred in 30% to 40% of relationships.8 In romantic relationships outside of marriage, between half to three quarters have featured cheating. From the 1940s to the 1980s, reports of infidelity in the United States steadily increased and it has been traced through many eras and cultures including ancient Greek, Roman, and Asian civilizations.9

It was initially proposed that women would perceive emotional infidelity as worse than sexual infidelity and that men would perceive sexual infidelity in their partners as worse than emotional infidelity. This proposal developed from the evolutionary psychology perspective, that predicts males would be concerned with sexual infidelity because they had no way of knowing whether their mate was carrying their child and thus carrying on their genetic material. On the other hand, women were more concerned with emotional infidelity because women feared that their male counterparts would become attached to another female and that his resources (e.g., money, time, etc.) would be directed toward them instead.

Although the evolutionary perspective provides insight into the basic differences that could exist between females and males, research consistently shows that both females and males find sexual infidelity to be worse than emotional infidelity.10 When sexual infidelity occurs, research shows that how infidelity is discovered determines relational outcomes.11 Voluntary admission seems to result in increased forgiveness, less likelihood of dissolution, and is the least damaging to relational quality.

Among the factors identified as increasing the likelihood that infidelity will occur are: lack of satisfaction with the relationship, low commitment to it, extroversion, neuroticism, psychopathy, relational power differentials, homosexuality, African American and Hispanic American ethnicity, lower levels of education, and working outside of the home. 9

Internet Infidelity

The amount of time spent online by a wide range of people makes the Internet a ripe “meeting place” for relationships of all types. The Internet shrinks our world and enables individuals to find others with similar interests, desirable knowledge (e.g., health information, how to clean, the best campgrounds, etc.), and attractive qualities. Moreover, the Internet provides privacy, the ability to interact frequently, and it enables a feeling of close proximity.

Research Spotlight

Tony Docan-Morgan and Carol A. Docan set out to examine how men and women view Internet infidelity in a 2007 study. The researchers started by having 43 undergraduates list what they thought could be Internet infidelity. The researchers reviewed the open-ended responses and paired down the list to the following:

- having cybersex (engaging in sexually explicit conversations with someone online)

- flirtatious behavior

- emotional connection

- seeking another partner

- exchanging private information

- casual conversation

Based on these categories and other literature on the subject, the researchers developed a measure of internet fidelity numbering 27 items. The measure ultimately discovered two different patterns of Internet infidelity superficial/informal acts (e.g., chatting about sports, talking about current events, joking, etc.) and involving/goal-directed (e.g., disclosing love, viewing personal ads, making plans to meet someone, etc.).

The researchers found that superficial/informal acts were rated as less severe than involving/goal-directed ones. Females found involving/goal-directed Internet infidelity as more severe than males did. In general, participants tended to rate their Internet infidelity as less severe than their partner’s on both involving/goal-directed and superficial/informal acts.

Docan-Morgan, T., & Docan, C. (2007). Internet infidelity: Double standards and the differing views of women and men. Communication Quarterly, 55(3), 317-342. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370701492519

Key Takeaways

- Infidelity involves “cheating,” or being unfaithful to a committed spouse or other sexual partner; when it involves extramarital sex, it is called adultery.

- Emotional infidelity and sexual/physical infidelity are distinct phenomena, though they may occur concurrently.

- The Internet is a particularly ripe context for acts of infidelity.

Exercises

- Would you expect a present or past romantic partner to have an easier time forgiving your sexual infidelity or your emotional infidelity with a co-worker? What is the reasoning for this?

- Where do you draw the line for whether emotional infidelity has occurred?

Jealousy

Infidelity, or the suspicion of it, is most often the underlying cause of jealousy. Jealousy is a set of “cognitive, emotional, and coping behaviors” in response to “a potential threat to, or an actual loss of a valued relationship due to a real or imagined rival for a partner’s attention.”12

In the Shakespeare play, Othello, the main character is experiencing jealousy at his wife, Desdemona’s, affection for Cassio. Othello is warned by his manipulative subordinate, Iago, that jealousy “is the green-eyed monster which doth mock.” The ancient Greeks, informed by Hippocrates’ medical practice based on humors, or substances, believed that jealousy was traceable to an overabundance of bile, that is green in color.

Dimensions of Jealousy

In contemporary times, jealousy is said to possess three dimensions.13 Cognitive jealousy is comprised by the thoughts and worries that plague us when we suspect a rival’s threat to a relationship. 14 Emotional jealousy is the affect dimension and can carry feelings of anxiety, discomfort, anger, fear, sadness, shame, and guilt.15 Behavioral jealousy includes the acts of observing, investigating, and reacting to, fears and suspicions about relational threats.16

The behaviors of jealousy might include relentlessly asking a partner about their whereabouts and activities and associations, showing up without notice to their work or social events, scrolling through their phone contacts and messages, recruiting others to report on them, and investigating them financially. Also, when jealous, some control their partner’s exposure to others, seek information from or threaten violence to rivals, mark their territory with labeling of their relationship and public displays of affection, and withdraw from partners or administer the silent treatment.17 As inevitable and unavoidable as such actions may seem in the throes of jealous episodes, they frequently lead to being self-disgusted and feeling pathetic.

The inextricable tangling of jealousy’s cognitions, emotions, and behaviors becomes aggravated by the potentially cheating partner’s denials or gaslighting (i.e.,falsely leading another to doubt their own ability to perceive reality accurately).

Unwarranted jealousy will take a toll on the falsely suspected partner. They begin to feel that they are restrained from their natural personality and behavior by fear of triggering their significant other’s jealous spirals.

Variance in Jealousy

Jealousy may adopt different values in different contexts. Laura Guerrero and Peter Andersen report a “paradoxical societal view of jealousy” so that it can be associated with love yet also with paranoia.17 It can be evaluated as reprehensible yet so essentially human that it has been employed as a defense in prosecutions of crimes of passion.

Moreover, the nature and extent of jealousy may vary between cultures. Stephen Croucher of the University of Jyväskylä, with seven colleagues at Marist College and the University of Oklahoma, administered a questionnaire survey to a huge sample (i.e., almost 1800 participants!) across four nations. They found that American, Irish, and Indian participants reported expressing more behavioral and emotional jealousy than did those in Thailand. The researchers believe that Thais could be less jealous due to living in a country that is less egocentric and masculine than the U.S. and Ireland, and less patriarchal than India.12

Key Takeaways

- Jealousy is the “green-eyed monster” that responds to threat to, or loss of, a relationship due to a rival for a partner’s attention.

- Jealousy tends to have cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions.

- Behavioral jealousy manifests as quizzing partners, showing up without notice, scanning phones, contacting rivals, and marking territory.

Exercises

- Describe why jealousy is sometimes described as paradoxical, meaning that it may have two opposing natures.

- Apart from the four nations examined in the Croucher et. al., study, what countries or cultures would you guess as featuring higher or lower than average levels of jealousy? Which of the three dimensions of jealousy would be most responsible for this?

Bullying

Bullying is a form of repeated communication or behavior by an aggressive individual of greater power who targets an individual perceived as weaker for harm or discomfort. Bullies use authority, size, power, social status, and intimidation to create fear in others. The negative consequences of suffering from bullying include helplessness, anxiety, and depression.18 Anecdotal evidence is also mounting that bullying can lead its victims to suicidal ideation and even the willingness to commit acts of mass violence.

In 2013, Jadin Bell, a 15-year-old bullied intensely online and in person for his sexuality, hung himself on an elementary school playground in his hometown of La Grande, Oregon.

The day before returning to school after the Covid lockdown in north London, 14-year-old Mia Janin sent a WhatsApp voice note to a friend,” Tomorrow’s going to be a rough day…I’m currently mentally preparing myself to be bullied tomorrow.” Boys at the school were bullying girls by rating their attractiveness online and posting faked nude photos of them. She was found dead in the family bathroom the next day by her mother.

In early 2024, a 17-year-old shooter injured four students and three staff members, and killed a 6th-grader, at Perry High School in Iowa. Multiple media features relayed findings of the shooter having been relentlessly bullied. According to reporters Anna Merod and Kara Arundel, “a substantial and growing body of research continues to find strong correlations between school shooters and bullying.”19

Researchers have created a typology of three kinds of bullying: physical, verbal, and relational. 20

Physical Bullying

Physical bullying involves hitting, kicking, pulling hair, harming possessions, giving a “wedgie,” or a plethora of other acts of aggravation or violence. Physical bullying can be prevented by observers, such as teachers or even peers. There are several Public Service Campaigns directed toward bystanders to let them know that they can help prevent or stop bullying. However, bullies may corner victims in private settings, knowing that the weaker individual will not be able to defend themselves.

Relational Bullying

The second type is relational bullying. This form of bullying is the manipulation of social relationships to inflict hurt upon another individual.21 This type of bullying includes withholding friendship or excluding from social groups. Relational bullying often increases as children age and physical bullying decreases.

Relational bullying is particularly problematic because it is very painful for victims, but cannot be readily observed nor easily prohibited. When two friends suddenly begin to exclude a third, the rejection is quite painful, but adolescents cannot be required to continue liking and including a third party. Females are more likely to engage in this form of bullying.22

When two of three close West Virginia friends, Sheila Eddy and Rachel Shoaf, grew closer, perhaps sexually, they estranged the third, Skylar Neese. In July of 2012, Neese was lured into the woods by the other two and brutally stabbed to death. This was a tragic case of relational bullying escalating into murderous physical bullying.

Verbal Bullying

The third type is verbal bullying and includes threats, degrading comments, teasing, name-calling, putdowns, or sarcastic comments.23 This form of bullying is easily observed and can be addressed by both authorities and peers. The effects of this form of bullying are similar to the impacts of physical and relational bullying, but self-esteem is especially vulnerable to it.

The negative consequences of childhood bullying have driven communication scholars to develop educational tools to provide to teachers and other authority figures. Researchers developed a model to assist teachers in discerning playful, prosocial teasing from destructive bullying.24 The Teasing Totter Model outlines behaviors that range from prosocial teasing to bullying and offers recommendations for responding to each. Teasing in a prosocial manner is usually done among friends, and laughter is involved, or even affection. Bullying, on the other hand, is a repeated negative behavior in which the victim is visibly distressed.

Cyberbullying

id=”560″]Cyberbullying[/pb_glossary] is intentional harm, inflicted through online and social media platforms, that is repeated over time.25 When using electronic communication technologies, young people are exposed to interpersonal violence, social aggression, harassment, and mistreatment.26 Cyberbullying includes behaviors such as flaming, which involves posting provocative or abusive posts, and outing or doxing, where personal information is posted.27 Cyberbullying affects victims academically and socially, with 20% of victims reporting Internet avoidance.27

Opportunities for bullying used to be confined to school or landline phones; it was essentially limited to eight hour school days and phone calls that could be avoided or ended easily. Now, cyberbullying take places 24/7, and the only way to avoid it is to cut off a major form of staying connected with the social world. Researchers are just now beginning to understand the impact of cyberbullying, and some speculate that cyberbullying is worse than traditional bullying, but research shows mixed results on this assertion.

Cyberbullying is so prevalent that social media such as Facebook have policies to help users avoid this phenomenon.

Facebook Suggestions for Victims of Cyberbullying

Facebook offers these tools to help with bullying and harassment. Depending on the seriousness of the situation:

- Unfriend — Only your Facebook friends can contact you through Facebook chat or post messages on your Timeline.

- Block — This will prevent the person from starting chats and messages with you, adding you as a friend and viewing things you share on your Timeline.

- Report the person or any abusive things they post.

- The best protection against bullying is to learn how to recognize it and how to stop it. Here are some tips about what you should — and shouldn’t — do:

- Don’t respond. Typically, bullies want to get a response — don’t give them one.

- Don’t keep it a secret. Use Facebook’s Trusted Friend tool to send a copy of the abusive content to someone you trust who can help you deal with the bullying. This will also generate a report to Facebook.

- Document and save. If the attacks persist, you may need to report the activity to authorities and they will want to see the messages.

Visit Facebook’s Family Safety Center for more information, tools and resources. https://www.facebook.com/help/116326365118751/

Key Takeaways

- Bullying is a form of repeated communication or behavior by an aggressive individual of greater power, who targets an individual perceived as weaker, for harm or discomfort.

- Physical, relational, and verbal are three types of bullying that are widely recognized.

- The consequences of bullying can be severe from damaged esteem to suicide or violence.

Exercises

- What precautions do you take to minimize the odds of being cyberbullied?

- Even if a teen or young adult has a history of being bullied, what other factors might contribute to their thoughts of becoming a school shooter?

Domestic Violence

“Domestic violence is the willful intimidation, physical assault, battery, sexual assault, and/or other abusive behavior as part of a systematic pattern of power and control perpetrated by one person against another. It includes physical violence, sexual violence, threats, and emotional/psychological abuse.”28

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) expands upon this definition to specifically label some acts of domestic violence as “intimate partner violence.”29 These include sexual violence, stalking, physical violence, and psychological aggression against a romantic or sexual partner, spouse, boyfriend, girlfriend, or person that is dating, seeing, or “hooking up” with the abuser. Domestic violence also includes acts between members of the same household or family.

One in four (i.e., 30 million) women and one in ten (i.e., 12.1 million) men have reported domestic partner violence-related impacts which include being fearful, concerned about safety, injury, need for medical care, needed help from law enforcement, missed at least one day of work, missed at least one day of school, any post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, need for housing services, need for victim advocate services, need for legal services, and contacting a crisis hotline.30

A typical cyclical narrative of repeated violence within a relationship sees tension, followed by explosion, followed by remorse, followed by a honeymoon period of apologies and promises to cease the behavior.

Of women, the predominant victimized sex, or others on the receiving end of domestic violence, it takes an average of 5 to 7 attempts to leave an abuser permanently. Some never try to leave and others lose their lives before they can. In fact, a study by the 2018 National Coalition Against Domestic Violence reported that every 6 hours in the United States, another woman is killed by her abuser.30 Domestic violence organizations and shelters provide resources that empower survivors to attempt to break the unfortunate, if not tragic, cycle.

Physical violence is common in instances of domestic violence, as is sexual violence, a specific form of domestic violence that may be experienced by women and men and includes rape, which can consist of being forcibly penetrated (or penetrating) someone else, sexual coercion, and unwanted sexual contact.

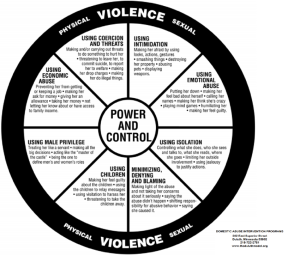

Still, domestic violence is not only about physical and sexual aggression. Abusers may be manipulative in the ways that they exert power and control over domestic violence survivors (see Figure 8). They may constrain their partners economically, threaten them with consequences for undesired behaviors, abuse emotionally, remove partners from social contexts for the purpose of isolating them, wield male privilege, use children as weapons, and adopt tactics of minimization, gaslighting, denial, and blaming of survivors.

Sally Fiona Kelly demonstrated that individuals who have committed violent acts in a relationship believe violence is acceptable and are prepared to use it, thus supporting a focus on changing beliefs and thoughts about violence as intervention.31 Though advice exists for current and potential survivors to reach out to trusted organizations or confidantes in order to secure help, many programs have been instituted to educate men, especially young ones, new visions about masculinity and respect of other people.

Some of the better known initiatives include Man Up, the White Ribbon Campaign, Men Can Stop Rape, and MVP – Mentors in Violence Prevention. The #metoo movement has also helped to instill a new sense of morality around the use and abuse of women and other survivors of harassment and violence.

What Can Individual Students Do To Combat Domestic Violence?

-

Focus on domestic violence in your policy speeches, health campaigns, capstone projects, and training sessions.

-

Ask anyone you suspect to be a (potential) DV survivor if they want to talk or if there is anything you can do.

-

Attend and promote public forums on gender and equity issues, such as “Take Back the Night” Marches that are held around the country.

-

Educate young men about the dangers of toxic and privileged masculinity.

-

Confront those who perform or endorse bullying, aggression, sexism, racism, or other forms of insensitivity and exclusion rather than remaining a silent bystander.

-

Support local, national, and international campaigns against domestic violence.

-

Be an advocate for women and for respecting them in relationships, with friends and family, in the locker room and the workplace, and on social media.

-

Vote with your wallet and your endorsements by not consuming media, following public figures, or using products that are aligned with hypermasculine principles or that degrade others.

Key Takeaways

- Domestic violence can happen to anyone, but women in the United States are very susceptible to serious or deadly attacks.

- Domestic violence often assumes the form of a cycle as regret and apologies calm things down before the violence surfaces again.

- The Domestic Violence Intervention Program’s Power and Control wheel illustrates how violence can be replaced or supplemented by acts of intimidation, isolation, and economic and social constraint.

Exercises

- Can you easily identify instances of movies or television programs that featured domestic violence? If so, did they make these experiences seem more, or less, realistic to you?

- Name three things you will start doing to change the moral environment and decrease the likelihood that acts of domestic violence occur?

Key Terms

accusations

Hurtful assignments of fault or blame.

acquiescent responses

Involve crying, conceding, or apologizing.

active verbal responses

Involve attacking the other, defending yourself, or asking for an explanation.

advising statements

Hurtfully call for a course of action.

behavioral jealousy

The acts of observing, investigating, and reacting to fears and suspicions about relational threats.

bullying

A form of repeated communication or behavior by an aggressive individual of greater power who targets an individual perceived as weaker for harm or discomfort.

cognitive jealousy

Thoughts and worries that plague one who suspects a rival’s threat to a relationship.

concealment

Deception that involves withholding, rather than fabricating, of information.

cyberbullying

Intentional harm, inflicted through online and social media platforms, that is repeated over time.

deception

‘‘A deliberate act perpetuated by a sender to engender in a receiver beliefs contrary to what the sender believes is true.”4

directives

Involve a negative order or command.

domestic violence

The willful intimidation, physical assault, battery, sexual assault, and/or other abusive behavior as part of a systematic pattern of power and control perpetrated by one intimate partner against another.”29

emotional jealousy

The affect dimension of jealousy that may carry feelings of anxiety, discomfort, anger, fear, sadness, shame, and guilt.

equivocation

Use of a statement that could be interpreted as having more than one meaning, for the sake of obscuring the whole truth.

evaluations

Messages that assess value or worth, which may be hurtful when delivering a negative assessment.

falsification

Deliberately presenting information that is untrue or fraudulent as factual.

gaslighting

Falsely leading another to doubt their own ability to perceive reality accurately.

infidelity

Behaviors of “cheating,” being unfaithful to a committed spouse or other sexual partner.

informative statements

Reveal unwanted information.

invulnerable messages

Range from ignoring the message to laughing.

jealousy

a set of “cognitive, emotional, and coping behaviors” in response to “a potential threat to, or an actual loss of a valued relationship due to a real or imagined rival for a partner’s attention.”12

jokes

Hurtful messages that involve a prank or witticism.

lies

Deceptive speech acts that result in the hurt of recipients.

physical bullying

Hitting, kicking, pulling hair, harming possessions, giving a “wedgie,” or a plethora of other acts of aggravation or violence.

questions

Asked in a way that implies something negative.

relational bullying

The manipulation of social relationships to inflict hurt upon another individual.

statements of desire

Harmfully express an individual preference.

threats

Messages that indicate a desire or the potential to inflict physical or psychological harm.

verbal bullying

Threats, degrading comments, teasing, name-calling, putdowns or sarcastic comments.

Notes

Messages that assess value or worth, which may be hurtful when delivering a negative assessment.

Hurtful assignments of fault or blame.

Involve a negative order or command.

Reveal unwanted information.

Harmfully express an individual preference.

Hurtfully call for a course of action.

Asked in a way that implies something negative.

Messages that indicate a desire or the potential to inflict physical or psychological harm.

Hurtful messages that involve a prank or witticism.

Involve attacking the other, defending yourself, or asking for an explanation.

Involve crying, conceding, or apologizing.

Range from ignoring the message to laughing.

‘‘a deliberate act perpetuated by a sender to engender in a receiver beliefs contrary to what the sender believes is true.”4

Deliberately presenting information that is untrue or fraudulent as factual.

Deception that involves withholding, rather than fabricating, of information.

Use of a statement that could be interpreted as having more than one meaning, for the sake of obscuring the whole truth.

Behaviors of "cheating," being unfaithful to a committed spouse or other sexual partner.

A set of "cognitive, emotional, and coping behaviors" in response to "a potential threat to, or an actual loss of a valued relationship due to a real or imagined rival for a partner's attention."12

Thoughts and worries that plague one who suspects a rival's threat to a relationship.

The affect dimension of jealousy that may carry feelings of anxiety, discomfort, anger, fear, sadness, shame, and guilt.

The acts of observing, investigating, and reacting to fears and suspicions about relational threat.

Falsely leading another to doubt their own ability to perceive reality accurately.

A form of repeated communication or behavior by an aggressive individual of greater power who targets an individual perceived as weaker for harm or discomfort.

Hitting, kicking, pulling hair, harming possessions, giving a “wedgie,” or a plethora of other acts of aggravation or violence.

The manipulation of social relationships to inflict hurt upon another individual.

Threats, degrading comments, teasing, name-calling, putdowns or sarcastic comments.

The willful intimidation, physical assault, battery, sexual assault, and/or other abusive behavior as part of a systematic pattern of power and control perpetrated by one intimate partner against another.”29