Relationships at Work

Learning Objectives

- Describe the concept of leader-member exchange theory and the three stages these relationships go through.

- Describe the four reasons why romantic workplace relationships develop.

- Summarize the findings related to how coworkers view romantic workplace relationships.

- List and explain the characteristics of coworker relationships.

- Differentiate among three types of coworker relationships.

- Describe the three ways coworkers go about disengaging from workplace relationships.

- Explain the role of (in)appropriate language in the workplace and how it helps or harms relationships.

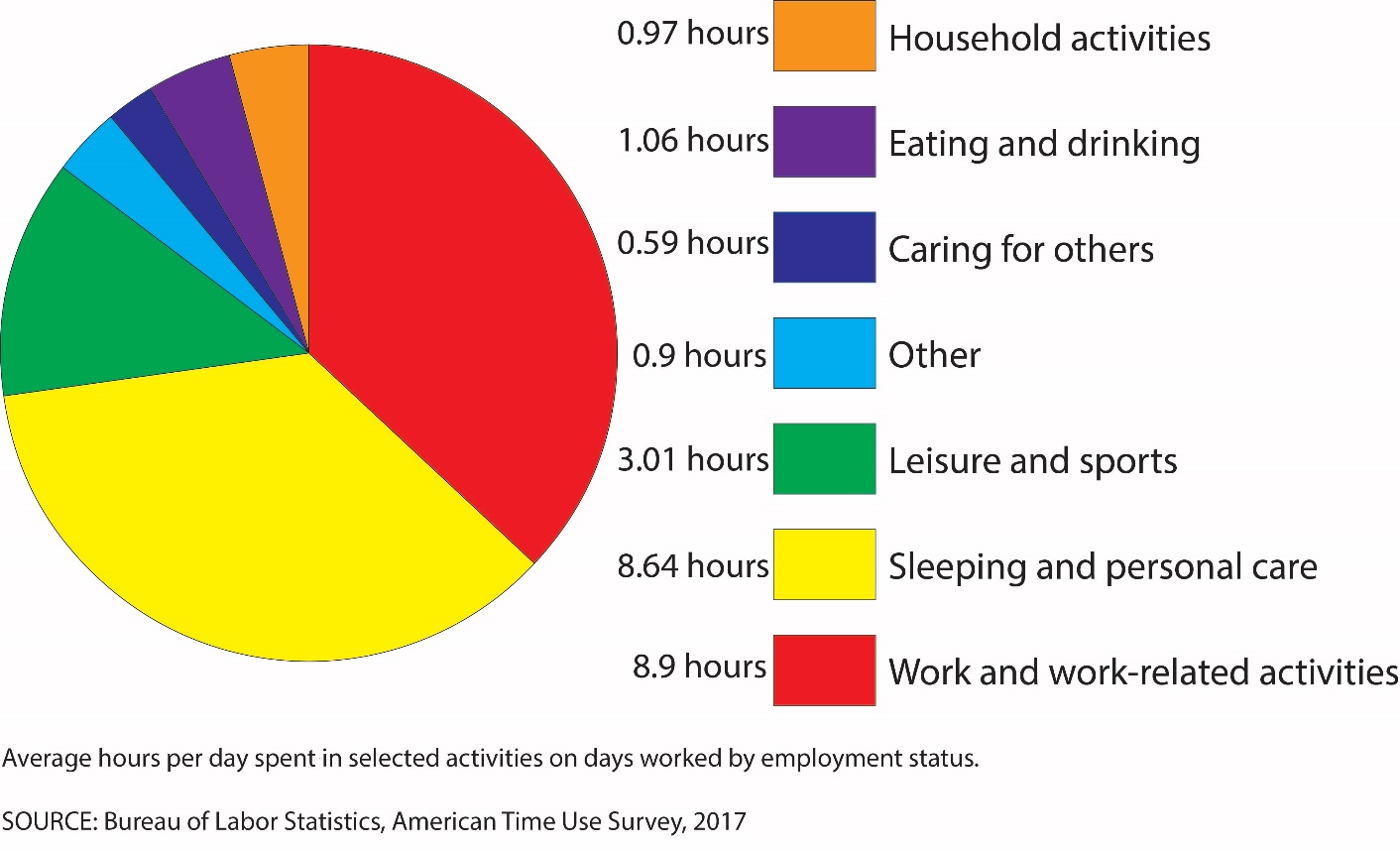

We spend more time with the people we work with than the people we live with during the five-day workweek. So, it shouldn’t be too surprising that our workplace relationships tend to be very important to our overall quality of life. In previous chapters, we’ve looked at the importance of a range of different types of relationships. In this chapter, we’re going to explore some areas directly related to workplace interpersonal relationships, including professionalism, leader-follower relationships, workplace friendships, romantic relationships in the workplace, and problematic workplace relationships. Finally, we’ll end this chapter by discussing essential communication skills for work in the 21st Century.

Leader-Follower Relationships

The Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Perspective on Leadership

Graen proposed a different type of theory for understanding relationships between leaders and followers, or ‘members.’16 In Graen’s leader-member exchange (LMX) theory, leaders have limited resources and can only take on high-quality relationships with a small number of followers. For this reason, some relationships are characterized as high-quality LMX relationships, but most relationships are characterized as low-quality LMX relationships. High-quality LMX relationships are those “characterized by greater input in decisions, mutual support, informal influence, trust, and greater negotiating latitude.”

In contrast, low-quality LMX relationships “are characterized by less support, more formal supervision, little or no involvement in decisions, and less trust and attention from the leader.”17 Ultimately, many positive outcomes happen for a follower who enters into a high LMX relationship with a leader. Before looking at some positive outcomes from high LMX relationships, we’re first going to examine the stages involved in the creation of these relationships.

Stages of LMX Relationships

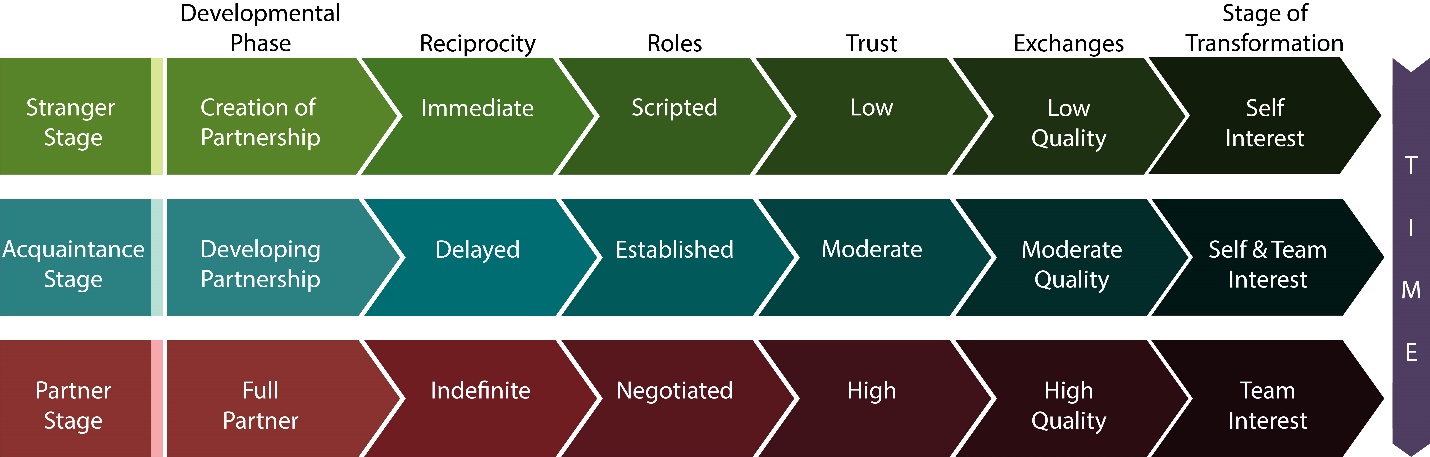

So, you may be wondering how LMX relationships are developed. Graen and Uhl-Bien18 created a three-stage model for the development of LMX relationships. Figure 3 represents the three different stages: stranger, acquaintance, and partner.

Stranger Stage

The first stage of LMX relationships is the stranger stage, and this is the beginning of the creation of an LMX relationship. Most LMX relationships never venture beyond the stranger stage because of the resources needed on both the side of the follower and the leader to progress further.

As you can see from Figure 3, the stranger stage is one where their self-interests primarily guide the follower and the leader. These exchanges generally involve what Graen and Uhl-Bien call a “cash and carry” relationship. Cash and carry refers to the idea that some stores don’t utilize credit, so all purchases are made in cash, and customers carry their purchased goods right then. In the stranger stage, interactions between a follower and leader follow this same process. The leader helps the follower and gets something immediately in return. Low levels of trust mark these relationships, and interactions tend to be carried out through scripted forms of communication within the normal hierarchical structure of the organization.

Acquaintance Stage

The second stage of high-quality LMX relationships is the acquaintance stage or exchanges between a leader and follower become more normalized and aren’t necessarily based on a cash and carry system. According to Graen and Uhl-Bien, “Leaders and followers may begin to share greater information and resources, on both a personal and work level. These exchanges are still limited, however, and constitute a ‘testing’ stage—with the equitable return of favors within a limited time perspective.”19 At this point, neither the leader nor the follower expects to get anything immediately in return within the exchange relationship. Instead, they start seeing this relationship as something that has the potential for long-term benefits for both sides. There also is a switch from purely personal self-interests to a combination of both self-interests and the interests of one’s team or organization.

Partner Stage

The final stage in the development of LMX relationships is the partner stage or the stage where a follower stops being perceived as a follower and starts being perceived as an equal or colleague. A level of maturity marks these relationships. Even though the two people within the exchange relationship may still have titles of leader and follower, there is a sense of equality between the individuals within the relationship.

Outcomes of High LMX Relationships

Ultimately, high LMX relationships take time to develop, and most people will not enter into a high LMX relationship within their lifetime. These are special relationships but can have a wildly powerful impact on someone’s career and life. The following are some of the known outcomes of high LMX relationships when compared to those in low LMX relationships:

- Increased productivity (both quality and quantity).

- Increased job satisfaction.

- Less likely to quit.

- Increased supervisor satisfaction.

- Increased organizational commitment.

- Increased satisfaction with the communication practices of the team and organization.

- Increased clarity about one’s role in the organization.

- Increased likelihood to go beyond their job duties to help other employees.

- Higher levels of success in their careers.

- Increased likelihood of providing honest feedback.

- Increased motivation at work.

- Higher levels of influence within their organization.

- Receive more desirable work assignments.

- Higher levels of attention and support from organizational leaders.

- Increased organizational participation. 20, 21, 22, 23

Research Spotlight

In a 2019 article, Omilion-Hodges and colleagues wanted to find out what young adults want in a manager. The researchers orally interviewed 22 undergraduate students, then tested a set of measures. Students reported the general desires they have for managers. They were:

- Mentor: Role model, leads by example, makes and leaves an impact, advocate, and life coach.

- Manager: The nuts and bolts of a functional organization, lack of personal relationship, monitor and delegate tasks, maintain the establishment, structured and organized, stick to the plan, follow rules and regulations, strictly business, rules, hierarchy, protocol, and proficient.

- Teacher: Dedicated, provide learning opportunities, supportive, dedicated to growth of the organization, information delegation, provides necessary resources, provides explicit directions and feedback, one-on-one instruction.

- Friend: Well-developed relationship outside of work, empathetic; support in all areas of your life, similarity, identity development, values employees as whole people, relationally focused.

- Gatekeeper: Removed from day-to-day operations, strategic, can help you advance or hold you back, rules and regulation abiding, restricts information at their discretion, communicates only to influence, controls the successes and or failures of followers. 26

Omilion-Hodges, L. M., Shank, S. E., & Packard, C. M. (2019). What young adults want: A multistudy examination of vocational anticipatory socialization through the lens of students’ desired managerial communication behaviors. Management Communication Quarterly, 33(4), 512–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318919851177

Coworker (Peer Relationships)

Characteristics of Coworker Relationships

According to organizational workplace relationship expert Patricia Sias, peer coworker relationships exist between individuals who exist at the same level within an organizational hierarchy and have no formal authority over each other.29 According to Sias, we engage in these coworker relationships because they provide us with mentoring, information, power, and support. Let’s look at all four of these.

Mentoring

First, our coworker relationships are a great source for mentoring within any organizational environment. It’s always good to have that person who is a peer that you can run to when you have a question or need advice. Because this person has no direct authority over you, you can informally interact with this person without fear of reproach if these relationships are healthy. We’ll discuss what happens when you have nonhealthy relationships in the next section.

Sources of Information

Second, we use our peer coworker relationships as sources for information. One of our coauthors worked in a medical school for a while. Our coauthor quickly realized that there were some people he could talk to around the hospital who would gladly let our coauthor know everything that was going on around the place. One important caveat to all of this involves the quality of the information we are receiving. By information quality, Sias refers to the degree to which an individual perceives the information they are receiving as accurate, timely, and useful. Ever had that one friend who always has great news, that everyone else heard the previous week? Yeah, not all information sources provide you with quality information. As such, we need to establish a network of high-quality information sources if we are going to be successful within an organizational environment.

Issues of Power

Third, we engage in coworker relationships as an issue of power. Although two coworkers may exist in the same run within an organizational hierarchy, it’s important also to realize that there are informal sources of power as well. In the next chapter, we are going to explore the importance of power within interpersonal relationships in general. For now, we’ll say that power can be useful and helps us influence what goes on within our immediate environments. However, power can also be used to control and intimidate people, which is a huge problem in many organizations.

Social Support

The fourth reason we engage in peer coworker relationships is social support. For our purposes, let’s define social support as the perception and actuality that an individual receives assistance, care, and help from those people within their life. Let’s face it; there’s a reason corporate America has been referred to as the concrete jungle, circuses, or theatres of the absurd. Even the best organization in the world can be trying at times. The best boss in the world will eventually get under your skin about something. We’re humans; we’re flawed. As such, no organization is perfect, so it’s always important to have those peer coworkers we can go to who are there for us. One of our coauthors has a coworker our coauthor calls whenever our coauthor needs to be “talked off the ledge.” Our coauthor likes higher education and loves being a professor, but occasionally something happens, and our coauthor needs the coworker to vent to about something that has occurred. For the most part, our coauthor doesn’t want the coworker to solve a problem; our coauthor just wants someone to listen as our coauthor vents. We all need to de-stress in the workplace, and having peer coworker relationships is one way we do this.

Other Characteristics

In addition to the four characteristics discussed by Sias, Methot30 argued that three other features are also important: trust, relational maintenance, and ability to focus.

Trust

Methot defines trust as “the willingness to be vulnerable to another party with the expectation that the other party will behave with the best interest of the focal individual.”31 In essence, in the workplace, we eventually learn how to make ourselves vulnerable to our coworkers believing that our coworkers will do what’s in our best interests. Now, trust is an interesting and problematic concept because it’s both a function of workplace relationships but also an outcome. For coworker relationships to work or operate as they should, we need to be able to trust our coworkers. The more we get to know our coworkers and know they have our best interests at heart, then the more we will ultimately trust our coworkers. Trust develops over time and is not something that is not just a bipolar concept of trust or doesn’t trust. Instead, there are various degrees of trust in the workplace. At first, you may trust your coworkers just enough to tell them surface level things about yourself (e.g., where you went to college, major, hometown, etc.), but over time, as we’ve discussed before in this book, we start to self-disclose as deeper levels as our trust increases. Now, most coworker relationships will never be intimate relationships or even actual friendships, but we can learn to trust our coworkers within the confines of our jobs.

Relational Maintenance

Dindia and Canary wrote that definitions of the term “relational maintenance” could be broken down into four basic types:

- To keep a relationship in existence;

- To keep a relationship in a specified state or condition;

- To keep a relationship in a satisfactory condition; and

- To keep a relationship in repair.32

Mithas argues that relational maintenance is a difficult task in any context. Still, coworker relationships can have a range of negative outcomes if organizational members have difficulty maintaining their relationships with each other. For this reason, Mithas defines maintenance difficulty as “the degree of difficulty individuals experience in interpersonal relationships due to misunderstandings, incompatibility of goals, and the time and effort necessary to cope with disagreements.”33

Imagine you have two coworkers who tend to behave in an inappropriate fashion nonverbally. Maybe one sits there and rolls their eyes at everything a coworker says, or perhaps uses exaggerated facial expressions to mock a coworker when they’re talking. Having these types of coworkers will cause us (as a third party witnessing these problems) to spend more time trying to maintain relationships with both of them. On the flip side, the relationship between our two coworkers will take even more maintenance to get them to a point where they can just be collegial in the same room with each other. The more time we have to spend trying to decrease tension or resolve interpersonal conflicts in the workplace, the less time we will ultimately have on our actual jobs. Eventually, this can leave you feeling exhausted feeling and emotionally drained as though you just don’t have anything else to give. Some coworker relationships can become so toxic that minimizing contact and interaction can be the best solution to avoid draining your psychological and emotional resources.

Ability to Focus

Have you ever found your mind wandering while you are trying to work? One of the most important things when it comes to getting our work done is having the ability to focus. Within an organizational context, Methot defines “ability to focus” as “the ability to pay attention to value-producing activities without being concerned with extraneous issues such as off-task thoughts or distractions.”34 When individuals have healthy relationships with their coworkers, they are more easily able to focus their attention on the work at hand. On the other hand, if your coworkers always play politics, stabbing each other in the back, gossiping, and engaging in numerous other counterproductive workplace (or deviant workplace) behaviors, then it’s going to be a lot harder for you to focus on your job.

Types of Coworker Relationships

Now that we’ve looked at some of the characteristics of coworker relationships, let’s talk about the three different types of coworkers research has categorized. Kram and Isabella35 found that there are essentially three different types of coworker relationships in the workplace: information peer, collegial peer, and special peer. Figure 5 illustrates the basic things we get from each of these different types of peer relationships.

Information Peers

Information peers are so-called because we rely on these individuals for information about job tasks and the organization itself. As you can see from Figure 13.5, there are four basic types of activities we engage information peers for information sharing, workplace socialization/onboarding, networking, and knowledge management/maintenance.

First, we share information with our information peers. Of course, this information is task-focused, so the information is designed to help us complete our job better.

Second, information peers are vital during workplace socialization or onboarding. Workplace socialization can be defined as the process by which new organizational members learn the rules (e.g., explicit policies, explicit procedures, etc.), norms (e.g., when you go on break, how to act at work, who to eat with, who not to eat with, etc.), and culture (e.g., innovation, risk-taking, team orientation, competitiveness, etc.) of an organization. Organizations often have a very formal process for workplace socialization that is called onboarding. Onboarding is when an organization helps new members get acquainted with the organization, its members, its customers, and its products/services.

Third, information peers help us network within our organization or a larger field. Half of being successful in any organization involves getting to know the key players within the organization. Our information peers will already have existing relationships with these key players, so they can help make introductions. Furthermore, some of our peers may connect with others in the field (outside the organization), so they could help you meet other professionals as well.

Lastly, information peers help us manage and maintain knowledge. During the early parts of workplace socialization, our information peers will help us weed through all of the noise and focus on the knowledge that is important for us to do our jobs. As we become more involved in an organization, we can still use these information peers to help us acquire new knowledge or update existing knowledge. When we talk about knowledge, we generally talk about two different types: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge is information that is kept in some retrievable format. For example, you’ll need to find previously written reports or a list of customers’ names and addresses. These are examples of the types of information that physically (or electronically) may exist within the organization. Tacit knowledge, on the other hand, is the knowledge that’s difficult to capture permanently (e.g., write down, visualize, or permanently transfer from one person to another) because it’s garnered from personal experience and contexts. Informational peers who have been in an organization for a long time will have a lot of tacit knowledge. They may have an unwritten history of why policies and procedures are the way they are now, or they may know how to “read” certain clients because they’ve spent decades building relationships. For obvious reasons, it’s much easier to pass on explicit knowledge than implicit knowledge.

Collegial Peers

The second type of relationships we’ll have in the workplace are collegial peers or relationships that have moderate levels of trust and self-disclosure and is different from information peers because of the more openness that is shared between two individuals. Collegial peers may not be your best friends, but they are people that you enjoy working with. Some of the hallmarks of collegial peers include career strategizing, job-related feedback, recognizing competence/performance, friendship.

pb_glossary id=”212″]Career strategizing[/pb_glossary] is the process of creating a plan of action for one’s career path and trajectory. We also often turn to those who are around us the most often to see how we are doing within an organization, receiving job-related feedback. Our collegial peers can provide us this necessary feedback to ensure we are doing our jobs to the utmost of our abilities and the expectations of the organization. Collegial peers are usually the first to recognize our competence in the workplace and recognize us for excellent performance. Generally speaking, our peers have more interactions with us on the day-to-day job than does middle or upper management, so they are often in the best position to recognize our competence in the workplace. Our competence in the workplace can involve having valued attitudes (e.g., liking hard work, having a positive attitude, working in a team, etc.), cognitive abilities (e.g., information about a field, technical knowledge, industry-specific knowledge, etc.), and skills (e.g., writing, speaking, computer, etc.) necessary to complete critical work-related tasks. Not only do our peers recognize our attitudes, cognitive abilities, and skills, they are also there to pat us on the backs and tell us we’ve done a great job when a task is complete.

Lastly, collegial peers provide us a type of friendship in the workplace. They offer us a sense of camaraderie in the workplace. They also offer us someone we can both like and trust in the workplace. Collegial peers are not a “best friend,” but they offer you friendships within the workplace that make work more bearable and enjoyable. At the collegial level, you may not associate with these friends outside of work beyond workplace functions (e.g., sitting next to each other at meetings, having lunch together, finding projects to work on together, etc.). It’s also possible that a group of collegial peers will go to events outside the workplace as a group (e.g., going to happy hour, throwing a holiday party, attending a baseball game, etc.).

Special Peers

The final group of peers we work with are called special peers. Special peer relationships “involves revealing central ambivalences and personal dilemmas in work and family realms. Pretense and formal roles are replaced by greater self-disclosure and self-expression.”36 Special peer relationships are marked by confirmation, emotional support, personal feedback, and friendship.

First, special peers provide us with confirmation. When we are having one of our darkest days at work and are not sure we’re doing our jobs well, our special peers are there to let us know that we’re doing a good job. They approve of who we are and what we do. These are also the first people we go to when we do something well at work.

Second, special peers provide us with emotional support in the workplace. Emotional support from special peers comes from their willingness to listen and offer helpful advice and encouragement. Kelly Zellars and Pamela Perrewé have noted there are four types of emotional social support we get from peers: positive, negative, non-job-related, and empathic communication.37 Positive emotional support is when you and a special peer talk about the positive sides to work. For example, you and a special peer could talk about the joys of working on a specific project. Negative emotional support, on the other hand, is when you and a special peer talk about the downsides to work. For example, maybe both of you talk about the problems working with a specific manager or coworker. The third form of emotional social support is non-job-related or talking about things that are happening in your personal lives outside of the workplace itself. These could be conversations about friends, family members, hobbies, etc. A good deal of the emotional social support we get from special peers has nothing to do with the workplace at all. The final type of emotional social support is empathic communication or conversations about one’s emotions or emotional state in the workplace. If you’re having a bad day, you can go to your special peer, and they will reassure you about the feelings you are experiencing. Another example is talking to your special peer after having a bad interaction with a customer that ended with the customer yelling at you for no reason. After the interaction, you seek out your special peer, and they will confirm your feelings and thoughts about the interaction.

Third, special peers will provide both reliable and candid feedback about you and your work performance. One of the nice things about building an intimate special peer relationship is that both of you will be honest with one another. There are times we need confirmation, but then there are times we need someone to be bluntly honest with us. We are more likely to feel criticized and hurt when blunt honesty comes from someone when we do not have a special peer relationship. Special peer relationships provide a safe space where we can openly listen to feedback even if we’re not thrilled to receive that feedback.

Lastly, special peers also offer us a sense of deeper friendship in the workplace. You can almost think of special peers as your best friend(s) within the workplace. Most people will only have one or maybe two people they consider a special peer in the workplace. You may be friendly with a lot of your peers (i.g., collegial peers), but having that special peer relationship is deeper and more meaningful.

Friendship Development in the Workplace

Sias and Cahill argue workplace friendships are developed by a series of influencing factors: individual/personal factors, contextual factors, and communication changes. 39 First, some friendships develop because we are drawn to the other person. Maybe you’re drawn to a person in a meeting because she has a sense of humor that is similar to yours, or maybe you find that another coworker’s attitude towards the organization is exactly like yours. Whatever the reason we have, we are often drawn to people that are like us. For this reason, we are often drawn to people who resemble ourselves demographically (e.g., age, sex, race, religion, etc.).

A second reason we develop relationships in the workplace is because of a variety of different contextual factors. Several contextual factors increase the likelihood of forming a friendship. Those who work in close proximity, being either physically close to one another or seeing each other often are more likely to form a friendship. Further, those who have task interdependence, relying on one another to accomplish a shared goal are also likely to become friends.40 Opportunity and prevalence are also common reasons for friendships to form. Friendship opportunity refers to the degree to which an organization promotes and enables workers to develop friendships within the organization. Not surprisingly, individuals who work in organizations that allow for and help friendships tend to be satisfied, more motivated, and generally more committed to the organization itself. Friendship prevalence, on the other hand, is less of an organizational culture and more the degree to which an individual feels that they have developed or can develop workplace friendships. You may have an organization that attempts to create an environment where people can make friends, but if you don’t think you can trust your coworkers, you’re not very likely to make workplace friends. 41

Lastly, as friendships develop, our communication patterns within those relationships change. For example, when we move from being just an acquaintance to being a friend with a coworker, we are more likely to increase the amount of communication about non-work and personal topics. When we transition from friend to close friend, Sias and Cahill note that this change is marked by decreased caution and increased intimacy. According to Sias and Cahill, “Because of the increasing amount of trust developed between the coworkers, they felt freer to share opinions and feelings, particularly their feelings about work frustrations. Their discussion about both work and personal issues became increasingly more detailed and intimate.”42

Ending Workplace Relationships

Like any relationship, a workplace friendship can end. Some friendships sour because one person moves into a position of authority of the other, so there is no longer perceived equality within the relationship. Other friendships occur when there is a relationship violation of some kind. Some friendships devolve because of conflicting expectations of the relationship. Maybe one friend believes that giving him a heads up about insider information in the workplace is part of being a friend, and the other person sees it as a violation of trust given to her by her supervisors. When we have these conflicting ideas about what it means to “be a friend,” we can often see a schism that gets created. So, how does an individual get out of workplace friendships? Sias and Perry discuss how colleagues disengage from relationships with their coworkers in three forms: state-of-the-relationship talk, cost escalation, and depersonalization.43 People may use one or more technique and do not necessarily progress through the three in any order.

The first strategy people use when disengaging from workplace friendships involves state-of-the-relationship talk. State-of-the-relationship talk is exactly what it sounds like; you officially have a discussion that the friendship is ending. The goal of state-of-the-relationship talk is to engage the other person and inform them that ending the friendship is the best way to ensure that the two can continue a professional, functional relationship.

The second strategy is cost escalation. Cost escalation involves tactics that are designed to make the cost of maintaining the relationship higher than getting out of the relationship. For example, a coworker could start belittling a friend in public, making the friend the center of all jokes, or talking about the friend behind the friend’s back. All of these behaviors are designed to make the cost of the relationship too high for the other person.

The final strategy involves depersonalization. Depersonalization happens when one coworker keeps all content focused on the tasks involved in work, avoiding discussion of personal matters. It can also occur when one coworker avoids the other, removing the benefits of proximity and interdependence by avoiding being in the same location as the coworker one is distancing form. According to Sias and Perry’s research, depersonalization tends to be the most commonly used tactic for friendship dissolution in the workplace.44

Key Takeaways

- People engage in workplace relationships for several reasons: mentoring, information, power, and support.

- We also engage in coworker relationships for trust, relational maintenance, and the ability to focus.

- There are three different types of workplace relationships: information peer, collegial peer, and special peer. Information peers are coworkers we rely on for information about job tasks and the organization itself. Collegial peers are coworkers with whom we have moderate levels of trust and self-disclosure and more openness that is shared between two individuals. Special peers, on the other hand, are coworkers marked by high levels of trust and self-disclosure, like a “best friend” in the workplace.

- There are three different ways that coworkers can disengage from coworker relationships in the workplace. First, individuals can engage in state-of-the-relationship talk with a coworker, or explain to a coworker that a workplace friendship is ending. Second, individuals can make the cost of maintaining the relationship higher than getting out of the relationship, which is called cost escalation. The final disengagement strategy coworkers can utilize, depersonalization occurs when an individual stops all the interaction with a coworker that is not task-focused or simply to avoids the coworker.

Romantic Relationships at Work

In 2014 poll conducted by CareerBuilder.com and Harris Interactive Polling, they found that 38% of U.S. workers had dated a coworker at least once, and 20% of office romances involve someone who is already married.45 According to the researchers, “Office romances most often start with coworkers running into each other outside of work (12 percent) or at a happy hour (11 percent). Some other situations that led to romance include late nights at work (10 percent), having lunch together (10 percent), and love at first sight (9 percent).” Furthermore, according to data collected by Stanford University’s “How Couples Meet and Stay Together” research project, around 12% of married couples meet at work.46 Meeting through friends is the number one way that people meet their marriage partners, but those who met at work were more likely to get married than those who met through friends.

In essence, workplaces are still a place for romance, but this romance can often be a double-edged sword for organizations. In the modern organization, today’s office fling can easily turn into tomorrow’s sexual harassment lawsuit.

Understanding Romantic Workplace Relationships

According to Pierce and colleagues a romantic workplace relationship occurs when “two employees have acknowledged their mutual attraction to one another and have physically acted upon their romantic feelings in the form of a dating or otherwise intimate association.”47 From this perspective, the authors noted five distinct characteristics commonly associated with workplace romantic relationships:

- Passionate desire to be with one’s romantic partner;

- Shared, intimate self-disclosures;

- Affection and mutual respect;

- Emotional fulfillment; and

- Sexual fulfillment/gratification.

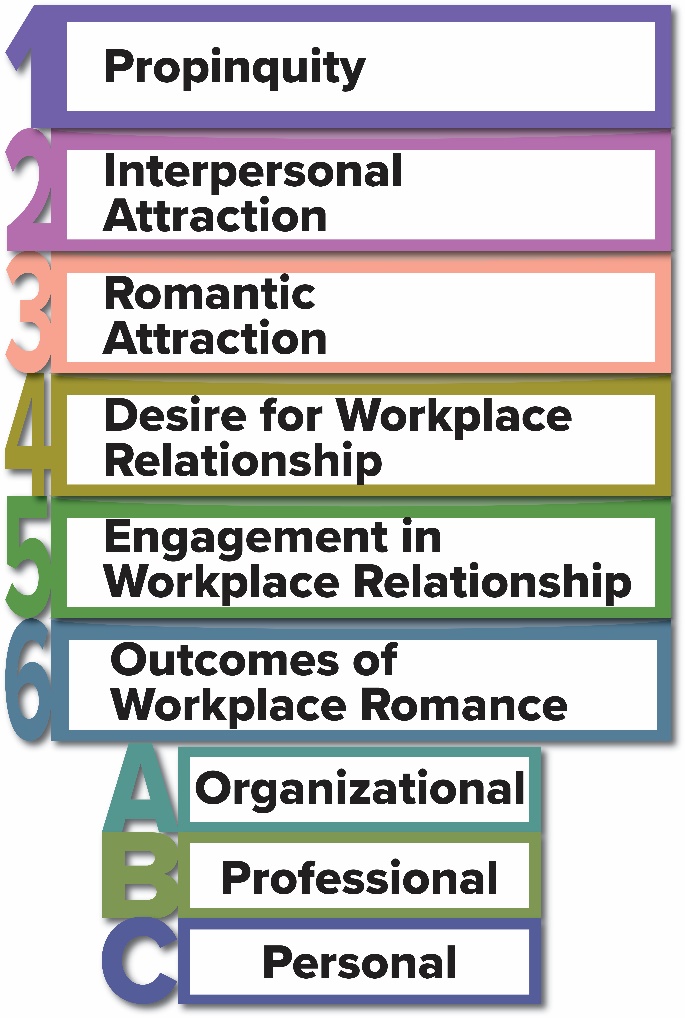

A Model of Romantic Workplace Relationships

In their article examining romantic workplace relationships, Pierce and colleagues proposed a model for understanding workplace relationships. Figure 6 is a simplified version of that basic model. The basic model is pretty easy to follow. First, it starts with the issue of propinquity, or the physical closeness of two people in a given space. One of the main reasons romantic relationships develop in the workplace is because we are around people in our offices every day. It’s this physical proximity that ultimately leads people to develop interpersonal attractions for some people. However, just because we find someone interpersonally attractive doesn’t mean we’re going to jump in a romantic relationship with them. Most people (if not all people) that we find interpersonally attractive at work will never develop romantic attractions towards. However, romantic attraction does happen. At the same time, if you don’t desire a workplace relationship, then even a romantic attraction won’t lead you to start engaging in a workplace relationship. If, however, you decide or desire to workplace relationship, then you are likely to start participating in that romantic workplace relationship.

Once you start engaging in a romantic workplace relationship, there will be consequences of that relationship. Now, some of these consequences are positive, and others could be negative. For our purposes, we broadly put these consequences into three different categories: personal, professional, and organizational.

Personal Outcomes

The first type of outcomes someone may face are personal outcomes or outcomes that affect an individual and not their romantic partner. Ultimately, romantic relationships can have a combination of both positive and negative outcomes for the individuals involved in them. For our purposes here, we will assume that both romantic partners are single and not in any other kind of romantic relationship. As long as that romantic relationship is functioning positively, individuals will be happy, which can positively impact someone’s job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and employee motivation. Employees engaged in romantic workplace relationships will even work longer hours so they can be with their romantic partners.

On the flip side, romantic relationships always have their ups and downs. If a relationship is not going well, then the individuals in those romantic workplace relationships can lead to adverse outcomes. In this case, we could see a decrease in job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and employee motivation. You could also see romantic partners trying to put more distance between themselves and their romantic partner at work. In these cases, you could see people avoid being placed on the same project or working longer hours to avoid extra time with their romantic partner.

Overall, it’s important to remember that romantic workplace relationships can lead to personal outcomes in the workplace environment. People often think they can keep their romantic and professional selves apart, but these distinctions can often become blurry and harder to separate.

Professional Outcomes

The second type of outcomes someone in a romantic workplace relationship may face are professional. According to Robert Quinn, there is a range of professional outcomes that can occur when someone is involved in a romantic relationship.48 Quinn listed six basic outcomes someone people achieve professionally as a result of engaging in a romantic workplace relationship: advancement, job security, increased power, financial rewards, easier work, job efficiency. Each of these professional outcomes are not guaranteed, and depend on the nature of the romantic relationship and who the partner is. If someone’s partner has more power within the organization, then they can show more favoritism towards their romantic power. Whereas, individuals on the same rung of the hierarchy, may not have the ability to create professional advancement.

There is also the flipside to professional outcomes. If a relationship starts to sour, someone could see their career advancement slowed, less job security, less power in the workplace, etc.… It’s in cases where romantic relationships sour (especially between individuals at different rungs of an organization’s hierarchy) when we start to see the real problems associated with romantic workplace relationships.

Organizational Outcomes

The final type of outcomes happens not directly to the individuals within a romantic workplace relationship, but rather to the organization itself. Organizations face a wide range of possible outcomes that stem from romantic workplace relationships. When romantic workplace relationships are going well, organizations have members who are more satisfied, motivated, and committed. Of course, this all trickles over into higher levels of productivity.

On the other hand, there are also negative outcomes that stem from romantic workplace relationships. First, people who are in an intimate relationship with each other in the workplace are often the subjects of extensive office gossip.49 And this gossiping is time-consuming and can become a problem from a wide range of organizational members. Second, individuals who are “dating their boss” can lead to resentment by their peers if their peers perceive the boss as providing any kind of preferential treatment for their significant other in the workplace. Furthermore, not all romantic workplace relationships are going to turn out well. Many romantic workplace relationships simply will dissolve. Sometimes this dissolution of the relationship is amicable, or both parties are OK with the breakup and can maintain professionalism after the fact. Unfortunately, there are times when romantic workplace relationships dissolve, and things can get a bit messy and unprofessional in the workplace. Although happy romantic workplace relationships have many positive side-effects, negative romantic workplace relationships can have the opposite outcomes for an organization leading to a decrease in job satisfaction, employee motivation, and organizational commitment, which leads to decreased productivity.

Many dissolutions of romantic workplace relationships could lead to formerly happy and productive organizational members looking for new jobs away from the person they were dating. In other cases (especially those involving people on different rungs of the organizational hierarchy), the organization could face legal claims of sexual harassment. Many organizations know that this last outcome is a real possibility, so they require any couple engaged in a romantic workplace relationship to enter into a consensual relationship agreement or “love contract” (see Side Bar for an example love contract). Other organizations ban romantic workplace relationships completely, and people found violating the policy can be terminated.

Why Romantic Workplace Relationships Develop

Robert Quinn was the first researcher to examine why individuals decide to engage in romantic workplace relationships.51 Renee Cowan and Sean Horan more recently updated the list of motives Quinn created.52 Cowan and Horan found that the modern worker engages in romantic workplace relationships for one of four reasons: ease of opportunity, similarity, time, and the hookup. The first three of these motives are very similar to other motives one generally sees in interpersonal relationships in general. Furthermore, these categories were not mutually exclusive categories. Let’s examine these motives in more detail

Ease of Opportunity

The first reason people engage in romantic workplace relationships; ease of opportunity happens because work fosters an environment where people are close to one another. We interact with a broad range of people in the workplace, so finding someone that one is romantically attracted to is not that surprising. This is similar to the idea of propinquity discussed by Pierce, Byrne, and Aguinis in their romantic workplace relationship development model discussed earlier in this chapter.53

Similarity

The second motive discussed by Cowan and Horan is similarity, or finding that others in the workplace may have identical personalities, interests, backgrounds, desires, needs, goals, etc.… As discussed earlier in this book, we know that when people perceive others as having the same attitude, background, or demographic similarities (homophily), we perceive them as more like us and are more likely to enter into relationships with those people. The longer we get to know those people, the greater that probability that we may decide to turn this into a special peer relationship or a romantic workplace relationship.

Time

As we discussed at the very beginning of this chapter, we spend a lot of our life at work. In a typical year, we spend around 92.71 days at work (50-weeks a year * 5 days a week * 8.9 hours per day). You ultimately spend more time with your coworkers than you do with almost any other group of people outside your immediate family. When you spend this much time with people, we learn about them and develop a sense of who they are and what they’re like. We also know that time is a strong factor when predicting sexual attraction.54

The Hook Up

Speaking of sexual attraction, the final motive people have for engaging in romantic workplace relationships was called “the hook up” by Cowan and Horan. The purpose of “the hook up” is casual sex without any romantic entanglements. Unlike the other three motives, this one is less about creating a romantic workplace relationship, and more about achieving mutual sexual satisfaction with one’s coworker. In Cowan and Horan’s study, they did note, “What we found interesting about this theme was that it was only attributed to coworker’s WRs. Although several participants described WRs they had engaged in, this motive was never attributed to those pursuit.”55

How Coworkers View Romantic Workplace Relationships

The final part of this section examines the research related to how coworkers view these romantic workplace relationships. The majority of us will never engage in a romantic workplace relationship, but most (if not all) of us will watch others who do. Sometimes these relationships work out, but often these relationships don’t. Some researchers have examined how coworkers view their peers who are engaging in romantic workplace relationships.

- Coworkers trust peers less when they were involved in a romantic workplace relationship with a supervisor than with a different organizational member.56

- Coworkers reported less honest and accurate self-disclosures to peers when they were involved in a romantic workplace relationship with a supervisor than with a different organizational member.57

- “[C]oworkers perceived a peer dating a superior to be more driven by job motives and less by love motives than they perceived peer dating individuals of any other status type.”58

- Coworkers reported that they felt their peers were more likely to get an unfair advantage when dating one’s leader rather a coworker at a different level of the hierarchy.59

- Peers dating subordinates were also felt to get an unfair advantage than peers dating people outside the organization.60

- Gay or lesbian peers who dated a leader were trusted less, deceived more, and perceived as less credible than a peer dating a peer.61

- “[O]rganizational peers are less likely to deceive gay and lesbian peers involved in WRs and to perceive gay and lesbian peers in WRs as more caring and of higher character than heterosexual peers who date at work.” 62

- Women who saw higher levels of sexual behavior in the workplace have lower levels of job satisfaction, but there was no relationship between observing sexual behaviors at work and job satisfaction for men.63

- When taking someone’s level of job satisfaction out of the picture, people who saw higher levels of sexual behavior in the workplace were more likely to look for another job.64

As you can see, dating in the workplace and open displays of sexuality in the workplace have some interesting outcomes for both the individuals involved in the relationship, their peers, and the organization.

Key Takeaways

- According to Charles Pierce, Donn Byrne, and Herman Aguinis, a romantic workplace relationship occurs when “two employees have acknowledged their mutual attraction to one another and have physically acted upon their romantic feelings in the form of a dating or otherwise intimate association.”

- Charles Pierce, Donn Byrne, and Herman Aguinis’ model of romantic workplace relationships (Seen in Figure 13.6) have six basic stages: propinquity, interpersonal attraction, romantic attraction, desire for romantic relationship, engage in workplace relationship, and outcomes of workplace relationship (personal, professional, and organizational).

- Renee Cowan and Sean Horan found four basic reasons why romantic workplace relationships occur: ease of opportunity, similarity, time, and the hookup. First, relationships develop because we are around people a lot, and we are naturally drawn to some people around us. Second, we perceive ourselves as similar to coworkers having identical personalities, interests, backgrounds, desires, needs, goals, etc.… Third, we spend a lot of time at work and the more we spend time with people the closer relationships become and can turn into romantic ones. Lastly, some people engage in romantic workplace relationships casual sex without any kind of romantic entanglements, known as the hookup.

- As a whole, the research on coworkers and their perceptions of romantic workplace relationships are generally more in favor of individuals (both gay/lesbian and straight) who engage in relationships with coworkers at the same level. Coworkers do not perceive their peers positively when they are dating someone at a more senior level (especially one’s direct supervisor). Furthermore, observing coworkers engaging in sexual behaviors tends to lead to decreases in job satisfaction, which can lead to an increase in one’s desire to find another job.

Language and Actions in the Workplace

Language Use

In the workplace, the type of language and how we use language is essential. A 2024 study showed the top skills for college graduates included written communication (72.7%), verbal communication (67.5%), problem-solving skills (88.7%), ability to work in a team (78.9%), and interpersonal skills (58.2%). Today’s workplace requires effective written and oral communication, and an ability to form and maintain personal and team relationships.12 From the moment someone sends in a resume with a cover letter, their language skills are being evaluated, so knowing how to use both formal language effectively and jargon/specialized language is paramount for success in the workplace.

Respect for Others

Our second category related to professionalism is respecting others. You’ve probably heard the saying “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all.” This guidance is particularly relevant to workplace interactions. Similarly, if you might caveat something with “Not to be racists but…” or “Not to be sexist but…” or “I’m not homophobic, but…” well, you get the idea and you probably don’t need to say the racist, sexist, or otherwise biased comment. From workplace bullying to sexual harassment, many people simply do not always treat people with dignity and respect in the workplace. So, what do we mean by treating someone with respect? There are a lot of behaviors one can engage in that are respectful if you’re interacting with a coworker or interacting with leaders or followers. Here’s a list we created of respectful behaviors for workplace interactions:

- Be courteous, polite, and kind to everyone.

- Do not criticize or nitpick at little inconsequential things.

- Do not engage in patronizing or demeaning behaviors.

- Don’t engage in physically hostile body language.

- Don’t roll your eyes when your coworkers are talking.

- Don’t use an aggressive tone of voice when talking with coworkers.

- Encourage coworkers to express opinions and ideas.

- Encourage your coworkers to demonstrate respect to each other as well.

- Listen to your coworkers openly without expressing judgment before they’ve finished speaking.

- Listen to your coworkers without cutting them off or speaking over them.

- Make sure you treat all of your coworkers fairly and equally.

- Make sure your facial expressions are appropriate and not aggressive.

- Never engage in verbally aggressive behavior: insults, name-calling, rumor mongering, disparaging, and putting people or their ideas down.

- Praise your coworkers more often than you criticize them. Point out when they’re doing great things, not just when they’re doing “wrong” things.

- Provide an equal opportunity for all coworkers to provide insight and input during meetings.

- Treat people the same regardless of age, gender, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, etc.…

- When expressing judgment, focus on criticizing ideas, and not the person.

Certainly there are a wide range of ways that you can show your respect for your coworkers, but it would be remiss if we didn’t bring up one specific area where you can demonstrate respect, the language we use. Without really intending to use language that is sex-based, we often do use terms that imbue biased meanings. Consider the phrase “grandfathered in” which is very common, this phrase has a biological sex connotation that limits it to males. The English language is filled with sexist language examples, and they come all too quickly to many of us because of tradition and the way we were taught the language. Thus, it is important to think about how we may (inadvertently) perpetuate sexist and biased language and how it impacts the workplace. Table 2 is a list of common sexist or biased language and corresponding inclusive terms that one could use instead.

| Sexist or Biased Language | Inclusive Term |

|---|---|

| Businessman | business owner, business executive, or business person |

| chairman | chairperson or chair |

| confined to a wheelchair | uses a wheelchair |

| congressman | congressperson |

| Eskimo | Inuit or Aleut |

| fireman | firefighters |

| freshman | first-year student |

| policeman | police officer |

| man or mankind | people, humanity, or the human race |

| man hours | working hours |

| man-made | manufactured, machine made, or synthetic |

| manpower | personnel or workforce |

| master (plan, bedroom) | blueprint, prototype, primary |

| Negro or colored | African American or Black |

| old people or elderly | senior citizens, mature adults, older adults |

| Oriental | Asian, Asian American, or specific country of origin |

| postman or mailman | postal worker or mail carrier |

| steward or stewardess | flight attendant |

| suffers from diabetes | has diabetes |

| to man | to operate; to staff; to cover |

| waiter or waitress | server |

Table 2. Replacing Sexist or Biased Language with Inclusive Terms

Personal Responsibility

Let’s face it; we all make mistakes. Making mistakes is a part of life. Personal responsibility refers to an individual’s willingness to be accountable for what they feel, think, and behave. Whether we’re talking about our attitudes, our thought processes, or physical/communicative behaviors, personal responsibility is simply realizing that we are in the driver’s seat and not blaming others for our current circumstances. Now, this is not to say that there are never external factors that impede our success. Of course, there are. This is not to say that certain people have a leg-up on life because of a privileged background, of course, some people have. However, personal responsibility involves differentiating between those things we can control and those things that are outside of our control. For example, I may not be able to control a coworker who decides to yell at me, but I can control how I feel about that coworker, how I think about that coworker, and how I choose to respond to that coworker. Here are some ways that you can take personal responsibility in your own life (or in the workplace):

- Acknowledge that you are responsible for your choices in the workplace.

- Acknowledge that you are responsible for how you feel at work.

- Acknowledge that you are responsible for your behaviors at work.

- Accept that your choices are yours alone, so you can’t blame someone else for them.

- Accept that your sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem are yours.

- Accept that you can control your stress and feelings of burnout.

- Decide to invest in your self-improvement.

- Decide to take control of your attitudes, thoughts, and behaviors.

- Decide on specific professional goals and make an effort and commitment to accomplish those goals.

Although you may have the ability to take responsibility for your feelings, thoughts, and behaviors, not everyone in the workplace will do the same. Most of us will come in contact with coworkers who do not take personal responsibility. Dealing with coworkers who have a million and one excuses can be frustrating and demoralizing.

Excuse-making occurs any time an individual attempts to shift the blame for an individual’s behavior from reasons more central to the individual to sources outside of their control in the attempt to make themselves look better and more in control.8 For example, an individual may explain their tardiness to work by talking about how horrible the traffic was on the way to work instead of admitting that they slept in late and left the house late. People make excuses because they fear that revealing the truth would make them look bad or out of control. In this example, waking up late and leaving the house late is the fault of the individual, but they blame the traffic to make themself look better and in control even though they were late.

Excuse-making happens in every facet of life, but excuse-making in the corporate world can be highly problematic. For example, research has shown that when front-line service providers engage in excuse-making, they are more likely to lose return customers as a result.9 In one study, when salespeople attempted to excuse their lack of ethical judgment on their customer’s lack of ethics, supervisors tended to punish more severely those who engaged in excuse-making than those who had not.10 Of course, even an individual’s peers can become a little annoyed (or downright disgusted) by a colleague who always has a handy excuse for their behavior. For this reason, Amy Nordam recommends using the ERROR method when handling a situation where your behavior was problematic: Empathy, Responsibility, Reason, Offer Reassurance.11 Here is an example Nordam uses to illustrate the ERROR method:

I hate that you [burden placed on person] because of me (Empathy). I should have thought things out better (Responsibility), but I got caught up in [reason for behavior] (Reason). Next time I’ll [preventative action] (Offer Reassurance).

As you can see, the critical parts of this response involve validating the other person, taking responsibility, and providing an explanation for how you’ll behave in the future to avoid similar problems.

Workplace Bullying Typology

Bullying is sadly alive and well in corporate America. This individual has a knack of being overly demanding on their peers, but then dares to take credit for their peers’ work when the time comes. This is your prototypical schoolyard bully all grown up and in an office job. In 2005, Charlotte Rayner and Loraleigh Keashly examined the available definitions for “workplace bullying” and derived at five specific characteristics:

- the experience of negative behavior;

- behaviors experienced persistently;

- targets experiencing damage;

- targets labeling themselves as bullied; and

- targets with less power and difficulty defending themselves.70

You’ll notice from this list that being a bully isn’t a one-off behavior for these coworkers. This behavior targets individuals in a highly negative manner, happens over a long period, and can have long-term psychological and physiological ramifications for individuals who are targeted. We should note that more often than not, bullies do not happen in isolation, but more often than not run in packs. For this reason, a lot of European research on this subject has been called mobbing instead of bullying. Sadly, this is an all-too-often occurrence in the modern work world. In a large study examining 148 international corporations through both qualitative and quantitative methods, Hodson et al., reported that 49 percent of the organizations they investigated had routine patterns of workplace bullying.71

Though it is hard to imagine among adults, bullying continues in the work environment. Bully can lead to loss of employment, poor attendance and depression. There are several typologies of bullying. In research conducted with nurses, a typology of bullying was created that is particularly comprehensive.72 The typology of these researchers includes the bullying behavior and related tactics. Workplace bullying behaviors involve those seen in Table 3. As you can see, workplace bullying behaviors involve a wide range of tactics.

| Behaviors | Tactics |

|---|---|

| Isolation and exclusion | Being ignored |

| Being excluded from conversation | |

| Being isolated from supportive peers | |

| Being excluded from activities | |

| Intimidation and threats | Raised voices or raised hands |

| Being stared at, watched and followed | |

| Tampering with or destroying personal belongings | |

| Compromising or obstructing patient care | |

| Verbal threats | Being singled out, scrutinized and monitored |

| Being yelled at or verbally abused | |

| Being stood over, pushed or shoved | |

| Belittlement and humiliation | |

| Verbal put-downs, insults or humiliation | |

| Spreading gossip | |

| Being given a denigrating nickname | |

| Blamed, made to feel stupid or incompetent | |

| Suggestions of madness and mental instability | |

| Mistakes highlighted publicly | |

| Damaging professional identity | Public denigration of ability or achievements |

| Questioning skills and ability | |

| Being given demeaning work | |

| Unsubstantiated negative performance claims | |

| Spreading rumors, slander, and character slurs | |

| Questioning competence or credentials | |

| Limiting career opportunities | Denial of opportunities that lead to promotion |

| Being overlooked for promotion | |

| Excluded from committees and activities | |

| Exclusion from educational opportunities | |

| Rostered to erode specialist skills | |

| Obstructing work or making work-life difficult | Relocation to make job difficult |

| Removal of administrative support | |

| Excluded from routine information | |

| Work organized to isolate | |

| Removal of necessary equipment | |

| Given excessive or unreasonable workload | |

| Sabotaging or hampering work | |

| Varying targets and deadlines | |

| Excessive scrutiny of work | |

| Denial of due process and natural justice | Denial of due process in meetings |

| Denial of meal breaks | |

| Compiling unsubstantiated written records | |

| Denial of sick, study or conference leave | |

| Unfair rostering practices | |

| Economic sanctions | |

| Rostering to lower-paid shift work | |

| Limiting the opportunity to work | |

| Dismissal from position | |

| Reclassifying position to lower status |

Table 3 Bullying in the Workplace: Behaviors and Tactics

Key Takeaways

- Respecting our coworkers is one of the most essential keys to developing a positive organizational experience. There are many simple things we can do to show our respect, but one crucial feature is thinking about the types of langue we use. Avoid using language that is considered biased and marginalizing.

- Personal responsibility refers to an individual’s willingness to be accountable for what they feel, think, and behave. Part of being a successful coworker is taking responsibility for your behaviors, communication, and task achievement in the workplace.

Research Spotlight

In 2017, Stacy Tye-Williams and Kathleen J. Krone wanted to examine the advice given to victims of workplace bullying. Going into this study, the researchers realized that a lot of the advice given to victims makes it their personal responsibility to end the bullying, “You should just stand up to the bully” or “You’re being too emotional this.”

In the current study, the researchers interviewed 48 people who had been the victims of workplace bullying (the average age was 28). The participants had worked on average for 5 ½ years in the organization where they were bullied. Here are the top ten most common pieces of advice victims received:

- Quit/get out

- Ignore it/blow it off/do not let it affect you

- Fight/stand up

- Stay calm

- Report the bullying

- Be quiet/keep mouth shut

- Be rational

- Journal

- Avoid the bully

- Toughen up

The researchers discovered three underlying themes of advice. First, participants reported that they felt they were being told to downplay their emotional experiences as victims. Second, was what the researchers called the “dilemma of advice,” or the tendency to believe that the advice given wasn’t realistic and wouldn’t change anything. Furthermore, many who followed the advice reported that it made things worse, not better. Lastly, the researchers noted the “paradox of advice.” Some participants wouldn’t offer advice because bullying is contextual and needs a more contextually-based approach. Yet others admitted that they offered the same advice to others that they’d been offered, even when they knew the advice didn’t help them at all.

The researches ultimately concluded, “The results of this study point to a paradoxical relationship between advice and its usefulness. Targets felt that all types of advice are potentially useful. However, the advice either would not have worked in their case or could possibly be detrimental if put into practice.”73 Ultimately, the researchers argue that responding to bullying must first take into account the emotions the victim is receiving, and that responses to bullying should be a group and not a single individual’s efforts.

Tye-Williams, S., & Krone, K. J. (2017). Identifying and re-imagining the paradox of workplace bullying advice. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 45(2), 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2017.1288291

Key Terms

career strategizing

The process of creating a plan of action for one’s career path and trajectory.

collegial peers

Type of coworker with whom we have moderate levels of trust and self-disclosure and more openness that is shared between two individuals.

cost escalation

A form of relational disengagement involving tactics that are designed to make the cost of maintaining the relationship higher than getting out of the relationship.

depersonalization

A form of relational disengagement where an individual stops all the interaction that is not task-focused or simply to avoids the person.

deviant workplace behavior

The voluntary behavior of organizational members that violates significant organizational norms and practices or threatens the wellbeing of the organization and its members.

ease of opportunity

Reason explaining romantic workplace relationships happen because work fosters an environment where people are close to one another.

excuse-making

Any time an individual attempts to shift the blame for an individual’s behavior from reasons more central to the individual to sources outside of their control in the attempt to make themselves look better and more in control.

followership

The act or condition under which an individual helps or supports a leader in the accomplishment of organizational goals.

formal language

Specific writing and spoken style that adheres to strict conventions of grammar that uses complex sentences, full words, and the third person.

informal language

Specific writing and spoken style that is more colloquial or common in tone; contains simple, direct sentences; uses contractions and abbreviations; and allows for a more personal approach that includes emotional displays.

information peers

Type of coworker who we rely on for information about job tasks and the organization itself.

jargon

The specialized or technical language particular to a specific profession, occupation, or group that is either meaningless or difficult for outsiders to understand.

leader-member exchange

Theory of leadership that explores how leaders enter into two-way relationships with followers through a series of exchange agreements enabling followers to grow or be held back.

personal responsibility

An individual’s willingness to be accountable for what they feel, think, and behave.

relational maintenance

“[T]he degree of difficulty individuals experience in interpersonal relationships due to misunderstandings, incompatibility of goals, and the time and effort necessary to cope with disagreements.”

romantic workplace relationship

When “two employees have acknowledged their mutual attraction to one another and have physically acted upon their romantic feelings in the form of a dating or otherwise intimate association.”65

similarity

Reason explaining romantic workplace relationships occur because people find coworkers have identical personalities, interests, backgrounds, desires, needs, goals, etc.

social support

The perception and actuality that an individual receives assistance, care, and help from those people within their life.

special peer

Type of coworker relationship marked by high levels of trust and self-disclosure; like a “best friend” in the workplace.

state-of-the-relationship talk

A form of relational disengagement where an individual explains to a coworker that a workplace friendship is ending.

the hookup

Reason explaining romantic workplace relationships occur because individuals want to engage in casual sex without any romantic entanglements.

Theory of leadership that explores how leaders enter into two-way relationships with followers through a series of exchange agreements enabling followers to grow or be held back.

relationships "characterized by greater input in decisions, mutual support, informal influence, trust, and greater negotiating latitude.”

relationships “characterized by less support, more formal supervision, little or no involvement in decisions, and less trust and attention from the leader.”

The perception and actuality that an individual receives assistance, care, and help from those people within their life.

Degree of difficulty individuals experience in interpersonal relationships due to misunderstandings, incompatibility of goals, and the time and effort necessary to cope with disagreements.

A type of relationship explicitly united in a common purpose and respect each other's abilities to work toward that purpose.

The voluntary behavior of organizational members that violates significant organizational norms and practices or threatens the wellbeing of the organization and its members.

Type of coworker who we rely on for information about job tasks and the organization itself.

The process by which new organizational members learn the rules (e.g., explicit policies, explicit procedures, etc.), norms (e.g., when you go on break, how to act at work, who to eat with, who not to eat with), and culture (e.g., innovation, risk-taking, team orientation, competitiveness) of an organization.

Type of coworker with whom we have moderate levels of trust, self-disclosure, and openness.

Type of coworker relationship marked by high levels of trust and self-disclosure; like a “best friend” in the workplace.

A form of relational disengagement where an individual explains to a coworker that a workplace friendship is ending.

A form of relational disengagement involving tactics designed to make the cost of maintaining the relationship higher than getting out of the relationship.

A form of relational disengagement where an individual stops all the interaction that is not task-focused or simply avoids the person.

When two employees have acknowledged their mutual attraction to one another and have physically acted upon their romantic feelings in the form of a dating or otherwise intimate association.

When romantic workplace relationships happen because work fosters an environment where people are close to one another.

An indicator of credibility or romantic potential, it is the sharing of qualities so as to be like another person.

When romantic workplace relationships occur because people put in a great deal of time at work, so they are around and interact with potential romantic partners a great deal of the average workday.

When romantic workplace relationships occur because individuals want to engage in casual sex without any romantic entanglements.

An individual’s willingness to be accountable for how they feel, think, and behave.

Any time an individual attempts to shift the blame for an individual’s behavior from reasons more central to the individual to sources outside of their control in the attempt to make themselves look better and more in control.

Workplace bullying involves isolation and exclusion, intimidation and threats, verbal threats, damaging professional identity, limiting career opportunities, obstructing work or making work-life difficult, and denial of due process and natural justice.