Family and Marriage Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Describe the term “family communication patterns” and the two basic types of family communication patterns.

- Explain family systems theory and its utility for family communication researchers.

- Understand the three different types of marital relationships.

- Differentiate sibling relationship types and maintenance strategies.

Families are one of the essential relationships that all of us have in our lifetimes. Admittedly, there are a wide range of family types: adopted families, foster families, stepfamilies, nuclear families, and the families we make. According to the latest research from the US Census Bureau, there are a wide range of different types of households in the United States today:

- Family households (83.48 Million)

- Married couple households (61.96 Million)

- Married couple households with own children (31.29 Million)

- Married couple households without own children (30.67 Million)

- Male householder, with own children (3.81 Million)

- Male householder, without own children (2.67 Million)

- Female householder, with own children (12.33 Million)

- Female householder, without own children (2.72 Million)

This chapter is going to explore the different types of family relationships and then end by looking at marriage.

Family Relationships

We interact within our families and begin learning our family communication pattern from the time we are born. Families are comparable to cultures in that each family has its own values, rituals, customs, beliefs, values, and practices. Interactions with other families reveal that there are vast differences between families. You may notice that the family down the street yells at each other almost constantly. Yelling is their baseline interaction, whereas another family never raises their voices and may seem to speak so infrequently that it appears that they have nothing to talk about within their family unit. These differences and our tendency as humans to make comparisons cause individuals to assess the value of the various styles of family communication.

Defining Family

One of the biggest challenges for family researchers has been to define the “family.” The ambiguity of the term “family” has often been seen in the academic literature. The definition of the family developed by Ernest W. Burgess was the first widely used definition by academics.1 The term “family” was described as “two or more persons joined by ties of marriage, blood, or adoption; constituting a single household; interacting and communicating with each other in their respective social roles of husband and wife, mother and father, son and daughter, brother and sister; and creating and maintaining a common culture.”2 According to Burgess a family must be legally tied together, live together, interact together, and maintain a common culture together. The first three aspects of Burgess’ definition are pretty easy to conceptualize, but the concept of common culture deserves further explanation. Common culture consists of those communication interactions (day-to-day communication) and cultural tools (communication acts learned from one’s culture previous to the marriage) that each person brings into the marriage or family. Burgess’ definition of the family was useful because he was the first to examine the family structure’s attempt to maintain a common culture, but it also has many serious problems that cannot be ignored. Burgess’ definition of the word “family” excludes single parent families, commuter families, bisexual, gay, lesbian, and transgendered/transsexual families, and families who do not choose to, or are unable to, have children.

After examining the flaws of Burgess’ definition of the word “family,” an anthropologist, George Peter Murdock, attempted to define the family, “Social group characterized by common residence, economic cooperation, and reproduction. It includes adults of both sexes, at least two of whom maintain a socially approved sexual relationship, and one or more children, own or adopted, of the sexually cohabiting adults.”3 Once again, this definition only allows for heterosexual couples who have children to be considered a family because of the “socially approved” sexual relationship clause.

Another problem with this definition deals with the required inclusion of children for a couple to be labeled as a family. Many couples are unable to have children. Yet other couples opt not to have children. Does this really mean that they are not families? Couples, with or without children, should be considered as family units. All in all, this definition gave more direction than the Burgess one, but it is still extremely ambiguous and exclusive.

Another anthropologist, Bronislaw Malinowski, was looking at tribal familial structures all over the world at the turn of the century and defined the family as having 1) boundaries, 2) common residence, and 3) mutual affection for one another.4 Malinowski’s definition deals primarily with the fact that in different cultures around the world, a family member may include anyone from the immediate family of origin who gave birth to a person, to any member of the society into which one is born. Many African tribes see the tribe as being the family unit, and the tribe takes it upon itself to raise the children.

The United States’ societal concept of the term “family” became very rigid during the 1950s when the family was depicted by social norms and the media as a mother, father, 2.5 offspring, and the family dog living together behind a white picket fence in the suburbs.5 Though this is currently what many Americans picture as the typical 1950s’ family, the reality was considerably different. According to Steven Mintz and Susan Kellog the family structure was very weak in the 1950s.6 Women started using tranquilizers as a method for dealing with normal household duties, and the divorce rate skyrocketed when compared with the 1940s. Currently, only around seven percent of U.S. families participate in the so-called “traditional” 1950s-style family.7

During the 1970s, a variety of psychologists attempted to define the term “family.” Arthur P. Bochner defined the family as “an organized, naturally occurring relational interaction system, usually occupying a common living space over an extended time, and possessing a confluence of interpersonal images which evolve through the exchange of messages over time.”8,9 Though this definition is broad enough to allow for a variety of relationships to be considered families, the definition is too vague. It has allowed almost anything to be considered a family. Take, for example, individuals who live in a dormitory setting either at a college or in the military. The first part of Bochner’s definition of family is that it has an organized, naturally occurring relational interaction system. In essence, this means that any group that has organization and interacts through various relationships accomplishes part of what it means to be a family. People who live in dormitories interact through various relationships on a regular basis. Whether it be relating with one’s roommate or with the other people who live in the rooms next to you, people in dorms do interact. Dormitories are generally highly organized. People are required to listen to complex directors and Resident Assistants (on a collegiate level). Also, with the myriad of dormitory softball teams and other activities, interaction occurs regularly.

The second part of Bochner’s definition of the family deals with occupying a common living space for an extended period. People who live in college dormitories do so for around a year. To many transient people, this can be seen as an extended period. The extended time clause is very awkward simply because of its ambiguity.

The last aspect of Bochner’s definition of the family deals with the possession of interpersonal images that evolve through communication. Many people who live in the same space will start to acquire many stories and anecdotes concerning those people with whom they are in close proximity.

A family has an ongoing relationship that is constantly functioning even when the individuals are forced to live apart from the family of origin. Once again, here is a definition that does not allow for a concise explanation that can be easily applied when analyzing a family unit.

To understand the concept of a family, the definitions should be combined in such a way that all types of family structures (e.g., single parent, LGBTQIA, non-married parents, etc.) are included. For our purposes a family is defined as two or more people tied by marriage, blood, adoption, or choice; living together or apart by choice or circumstance; having interaction within family roles; creating and maintaining a common culture; being characterized by economic cooperation; deciding to have or not to have children, either own or adopted; having boundaries; and claiming mutual affection. This does not necessarily say that all types of families are healthy or legal, but that all cohabiting groups that consider themselves to be families should be researched as such to understand the specific interactions within the group. Though one may disagree with a specific family group, understanding the group through a family filter can lend itself to a better understanding than could be reached by analyzing the group through an organizational filter. To understand this definition of family, an analysis of the various aspects of this study’s definition shall be done to help clarify this definition.

Marriage, Blood, Adoption, or Choice

The first part of the definition says that a family is “two or more people tied by marriage, blood, adoption, or choice.” This part of the definition allows for a variety of family options that would not be accepted otherwise. This definition also allows for children who become part of a foster family to have a family that they can consider their own, even if they are switched from family to family. Non-married couples who consider themselves a family should also be researched as such. This aspect of the definition does open itself to some family types that are seen as illegal (e.g., family members marrying each other). This definition does not attempt to create a legal definition of family as much as it attempts to create a definition under which the family can be studied. As mentioned earlier, not all forms of family are necessarily healthy or legal. This part of the definition opens the field of family study while the remaining criteria narrow the focus so that not just any group can call itself a family.

Cohabitation

The second part of the definition of family indicates that the cohabitants may live together or apart by choice or circumstance. There are a variety of married couples who are not able to live in the same place because of occupation. According to Naomi Gerstel and Harriet Engel Goss, a commuter family is such a family:

The existence of marriages in which spouses separate in the service of divergent career demands at least suggests a need to question both the presupposition that coresidence is necessary for marital viability and its corollary that husbands and wives necessarily share economic fates. Dubbed “commuter,” “long-distance” or “two location” families, these marriages entail the maintenance of two separate residences by spouses who are apart from one another for periods ranging from several days per week to months at a time.10

These marriages, seen as nontraditional by many, are becoming an increasingly more common occurrence within the United States. Any member of the military who is stationed in the United States and sent to other parts of the world without their family experiences the problems caused by commuter marriages. Just because these families are not able to live under the same roof does not mean that they are not a family.

Family Roles

The third criterion of the definition of “family” suggests that the persons interact within family roles. These roles include such terms as mom, dad, son, daughter, wife, husband, spouse, and offspring. When an adult decides to be the guardian either by birth, adoption, or choice, the adult has taken on the role of a father or mother. When a group takes on the roles of parental figures and child figures, they have created a family system within which they can operate. Some of these roles can be related to the understanding of extended family as well, such as grandmother, aunt, uncle, niece, nephew, and the like. These roles and the rules that cultures associate with them have a definite impact on how a family will function.

Common Culture

The fourth aspect, creating a common culture, stems directly from Burgess’ definition.11 Couples bring other aspects (communicative acts, history, cultural differences, etc.) of their lives into the family to create the new subculture that exists in the new family. This can be done whether you have two men, a mother and daughter, or a husband and wife. When a couple joins to create a family unit, they are bringing both of their cultural backgrounds to the union, thus creating a unique third family culture that combines the two initial family cultures.

Economic Cooperation

The fifth trait of a family deals with economic cooperation, or the general pooling of family resources for the benefit of the entire family. Economic cooperation is typically thought of in the context of nuclear families, but in commuter families, both units typically pool their resources in order to keep both living establishments operational. Even though the family is unable to live together, the funds from both parties are used for the proper upkeep and maintenance of each location. In many instances, overseas military men and women will send their paychecks to their families back in the states because they will not need the money while they are out at sea or abroad, and their families still have bills that must get paid. Economic cooperation allows families who have dual earners to establish a more egalitarian relationship between the spouses since no one person is seen as the worker and the other as the non-worker.

Children

The sixth component of the definition of a family deals with children as a component of a family. Many researchers (Burgess, 1926; Murdock, 1949; Bailey, 1988) have said that for a family to exist, it must have offspring.12 This would mean that a couple who is infertile and only wants to raise children if they are biologically related would not be considered a family. This also prevents couples who do not desire to have children from achieving a family status. There are many unions of people who are not able to have children or do not desire to have children who are clearly families.

Established Boundaries

The seventh characteristic of a family deals with the need for the family to establish boundaries. Family boundaries is a concept that stems from family systems theory. According to Janet Beavin Bavelas and Lynn Segal, boundaries are those aspects of a family that prevent the family from venturing beyond the family unit.13 Boundaries function as a means for a family to determine the size and the scope of family interactions with the greater system or society. The family can let information into the family or exclude it from the family.

Families do not function entirely in conjunction with the system of which they are a part. Families must filter information or risk information overload. Families have naturally occurring and created boundaries that decide how a family should and should not operate. Many families create boundaries that deal with religious discussion, or they do not allow for any rejection of the family’s religious beliefs on any level. This is an example of a boundary that a family can create. Conversely, there are boundaries that a family must respect because of societal laws. Understanding these boundaries is necessary because it allows the researcher a greater understanding of the context in which the family lives.

Love and Trust

The eighth, and final, trait of a family, mutual affection, deals with the concept of love and trust that a family tends to possess to help them journey through conflict situations. Mutual affection also means that an individual must have a desire to be within the family or possess the freedom to leave the family system when they are of age. Families are not coercive entities but entities in which all participants can make personal decisions freely belong. Leaving the family system does not guarantee that a member of a family will be able to lose all connections to the family itself. Besides, the family will have had an impact on members that will affect them even if they leave the family of origin and cut all ties.

Understanding the definitions presented about the family and their obvious limitations will help the understanding of the usefulness of this new definition. Too often, definitions of the word “family” have been so narrow in scope that only some families were studied, and thus the research into the family came from only a very narrow and rigid perspective. Defining what constitutes a family is a difficult task, but without a clear definition, the study of family communication cannot be done effectively.

Family Communication Patterns

Two communication researchers, Jack M. McLeod and Steven H. Chaffee, found that most models of families relied on dichotomous ideas (e.g., autocratic/democratic, controlling/permissive, modern/traditional; etc.).14 Instead of relying on these perspectives, McLeod and Chaffee realized that family communication happens along two different continuums: socio-orientation and concept-orientation. In a series of further studies, David Ritchie and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick identified two family communication patterns: conformity orientation and conversation orientation.15, 16

Socio-Orientation

To McLeod and Chaffee, socio-oriented (conformity oriented) families are indicated by “the frequency of (or emphasis on) communication that is designed to produce deference, and to foster harmony and pleasant social relationships in the family.”17 Families high in socio-orientation tend to communicate a similarity of attitudes, beliefs, and values. Similarity and harmony are valued while conflict s avoided. Family members maintain interdependence within a hierarchical structure. One of the authors comes from a family where similarity and harmony were valued to the extent that any amount of disagreement was frowned upon. The parent never (literally) argued or disagreed in front of the children. Despite the desires of her parents, the personalities of the children soon emerged and revealed that neither child could go along with total similarity and harmony. One child dealt with this difference by learning to keep his opinions to himself. The other sibling, who happened to be the oldest child, never learned to keep her opinion to herself. Her communication style simply did not align with the conformity orientation friction was the result. You may have similar experiences if your communication style is different from your family’s communication orientation.

Concept-Orientation

To McLeod and Chaffee, concept-oriented (conversation oriented) families use “positive constraints to stimulate the child to develop his own views about the world. and to consider more than one side of an issue.”18 High concept-orientation families engage in open and frequent communication. Family life and interactions are perceived to be pleasurable. Self-expression is encouraged when attempting to make family decisions. Parents/guardians and children communicate in such a way that parents/guardians socialize and educate their children. Understanding the communication pattern within a family can lead to the ability to adapt to the family communication pattern rather than consistently communicating in a manner that is uncomfortable within the family structure.

Four Combinations

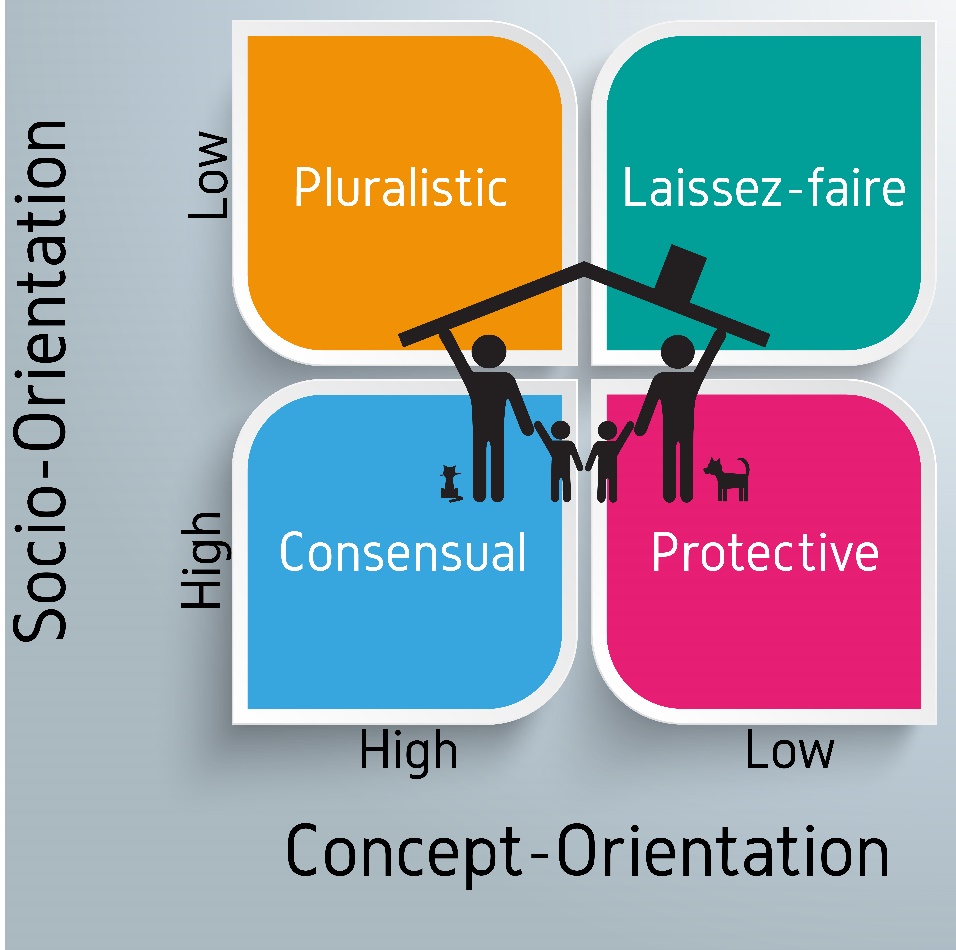

To further explain the concepts of socio- and concept-orientations, Jack M. McLeod and Steven H. Chaffee broke the combinations into four specific categories (Figure 2).

Consensual

The first family communication pattern is the consensual family, which is marked by both high levels of socio- and concept-orientation (high conversation and conformity). The term “consensual” is used here because there is a tendency in these families to strive for or have pressure for agreement between parents/guardian and children. Children are encouraged to think outside the book as long as it doesn’t impact the parents/guardians’ power or the family hierarchy. However, “These conflicting pressures may induce the child to retreat from the parent/guardian-child interaction. There is some evidence of ‘escape’ by consensual children, such as strikingly heavy viewing of television fantasy programs.”19

Protective

The second type of family communication pattern is the protective family, which is marked by high levels of socio-orientation and low levels of concept-orientation (high conformity, low conversation). In these families, there tends to be a strong emphasis on child obedience and family harmony. As such, children are taught that they should not disagree with their parents/guardians openly or engage in conversations where differences of opinion may be found. McLeod and Chaffee noted that parents/guardians strive to protect their children from any kind of controversy, which may actually make them more vulnerable to outside pressures and persuasion because they have not been taught how to be critical thinkers.

Pluralistic

The third type of family communication pattern is pluralistic, which is the opposite of the protective family and marked by high levels of concept-orientation and low levels of socio-orientation (low conformity, high conversation). In these families, “The emphasis in this communication structure seems to be on mutuality of respect and interests: the combination of an absence of social constraint plus a positive impetus to self-expression should foster both communication and competence.”20 Some parents/guardians worry that this type of openness of thought actually creates problems in their children, but McLeod and Chaffee noted that these families have children who say they are more likely to want to grow up and be like their parents/guardians than the other three types.

Laissez-faire

The final family communication pattern, laissez-faire, is marked by both low concept- and socio-orientations (low conversation, low conformity). In these families, there tends to be a lack of parent-child interaction or co-orientation. Instead, these children are more likely to be influenced by external factors like the media, peers, and other forces outside of the family unit. McLeod and Chaffee said that these children are more like a control group in an experiment because of the hands-off nature of their communicative relationships with their patterns. As such, it’s somewhat difficult to discuss the effectiveness of this study of family communication.

Research Spotlight

In a 2018 study by Kelly G. Odenweller & Tina M. Harris, the researchers set out to examine the relationship between family communication patterns and adult children’s racial prejudice and tolerance. The researchers used a mostly college-age sample of 190 adults.

Parental use of socio-oriented family communication patterns was positively related to an adult child’s reported levels of prejudiced and bias towards their own group, and negatively related to being racially tolerant. As for concept-orientation, there were no relationships found at all.

Ultimately, a parent’s conformity oriented family communication style can affect their children’s racial biases.

Odenweller, K. G., & Harris, T. M. (2018). Intergroup socialization: The influence of parents’ family communication patterns on adult children’s racial prejudice and tolerance. Communication Quarterly, 66(5), 501–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2018.1452766

Family Systems Theory

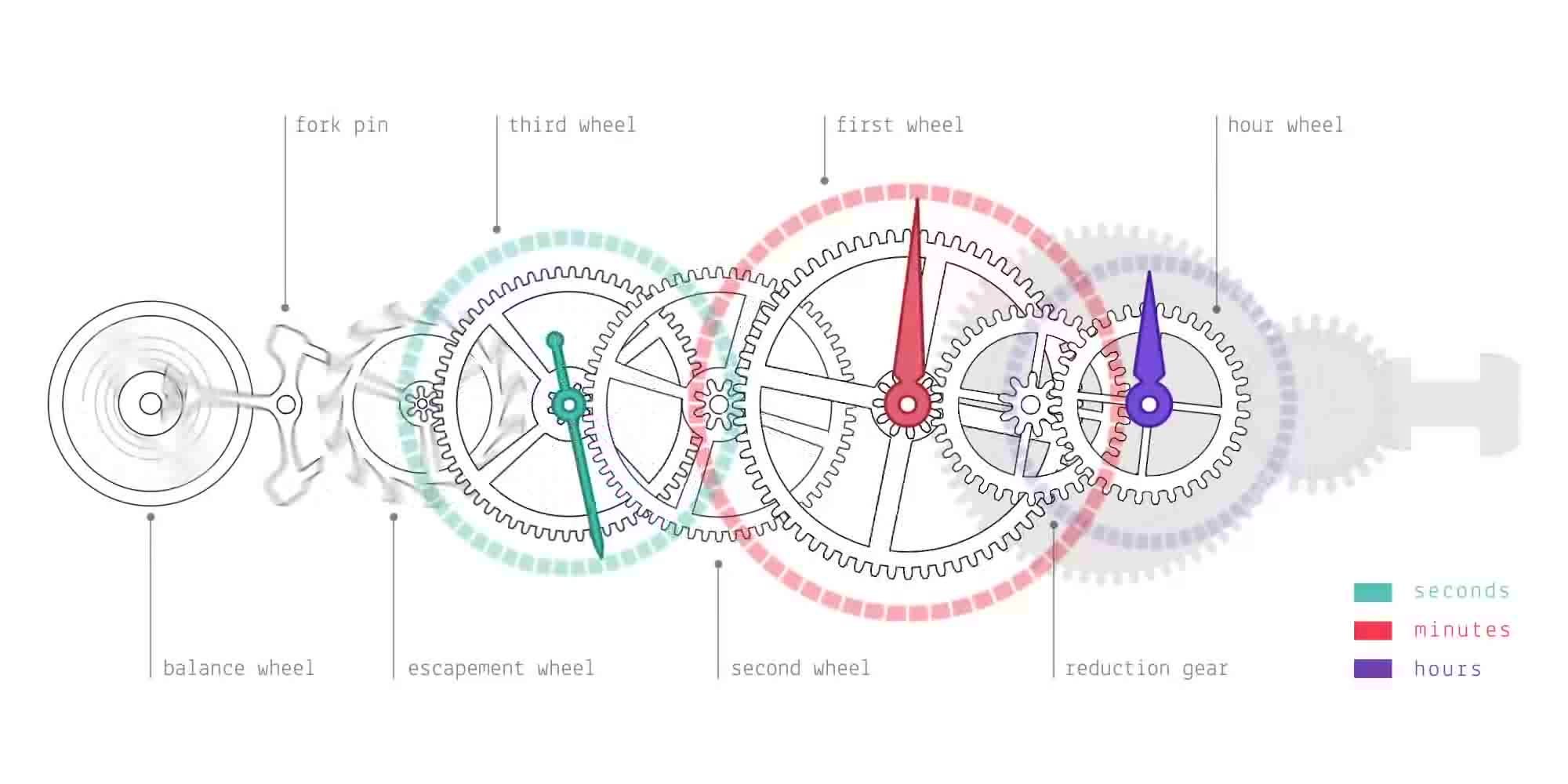

At the turn of the 20th Century, philosophers started questioning how humans organize things and our understanding of organizing. Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s general systems theory conceptualized what has become known as general systems theory.22 Bertalanffy defined a system as “sets of elements standing in interrelation.”23 A classic mechanical system is a non-digital watch. Figure 3 shows the basic layout of a watch’s innards.

In this illustration, we see how the balance wheel causes the fork pin to move, which turns the escapement wheel. The escapement wheel turns the third wheel (seconds), which turns the second wheel, which turns the first wheel (minutes), which turns the reduction gear, which turns the hour wheel. All of these different parts must work together to tell time. If a problem arises at any part of this process, then it will affect the entire system and our ability to tell time accurately.

So, how does this ultimately help us understand family communication? A psychiatrist named Murray Bowen developed family systems theory in the 1950s while working at the National Institute of Mental Health, which stemmed from the work of general systems theory discussed by Bertalanffy.24 Like Bertalanffy, Bowen’s theory started by examining how everything exists within nature and was governed by natural processes. Two of these processes, individuality and togetherness, became central to these ideas.25Individuality is a “universal, biological life force that propels organisms toward separateness, uniqueness, and distinctiveness.”26 Togetherness, on the other hand, is “the complementary, universal, biological life force that propels organisms toward relationship, attachment, and connectedness.”27 This essential dialectical tension creates an organism’s differentiation, or its drive to be both individualistic while maintaining intimate connections with others in the larger environment. This more ecological view of how humans exist becomes a central tenant of Bowen’s family systems theory. Bowen argues that human behavior was not greatly determined by social-construction or intra-psychically generated. Instead, Bowen believes that a great deal of human behavior is habitual and rooted in billions of years of evolutionary history.

In his earliest work, Bowen examined schizophrenic patients, so he was interested in the development and treatment of schizophrenia. Instead of focusing just on the schizophrenic patient, Bowen started analyzing the broader range of relationships within the individual family units. Ultimately, Bowen argued that schizophrenia might be an individual diagnosis, but is in reality, “a symptom manifestation of an active process that involves the entire family.”28 Dr. Bowen goes on to rationalize, “When schizophrenia is seen as a family problem, it is not a disease in terms of our usual way of thinking about disease… When the family is viewed as a unit, certain clinical patterns come into focus that are not easily seen from the more familiar individual frame of reference.”29 In essence, when we stop to think about a family as a system, it’s much easier to understand the manifestations of behaviors of family members.

Characteristics of Family Systems

Over the years, numerous researchers have furthered the basic ideas of Murray Bowen to further our understanding of family systems. Part of this process has been identifying different characteristics of family systems. According to Kathleen Galvin, Fran Dickson, and Sherilyn Marrow,30 there are seven essential characteristics of family systems: interdependence, wholeness, patterns/regularities, interactive complexity, openness, complex relationships, and equifinality.

Interdependence

The term interdependence means that changes in one part of the system will have ramifications for other parts of the system. For example, if one of the gears in your watch gets bent, the gear will affect the rest of the watch’s ability to tell time. In this idea, the behaviors of one family member will impact the behaviors of other family members. To combine this idea with family communication patterns described earlier, parents/guardians that are high in socio-orientation and low in concept-orientation will impact that children’s willingness and openness to communicate about issues of disagreement.

On the larger issue of pathology, numerous diseases and addictions can impact how people behave and interact. If you have a family who has a child diagnosed with cancer, the focus of the entire family may shift to the care of that one child. If the parents/guardians rally the family in support, this diagnosis could bring everyone together. On the other hand, it’s also possible that the complete focus of the parents/guardians turns to the ill child and the other children could feel unattended to or unloved, which could lead to feelings of isolation, jealousy, and resentment.

Wholeness

The idea of wholeness or holism is to be able to see behaviors and outcomes within the context of the system. To understand how a watch tells time, you cannot just look at the fork pin’s activity and understand the concept of time. In the same way, examining a single fight between two siblings cannot completely let you know everything you need to know about how that family interacts or how that fight came to happen. How siblings interact with one another can be manifestations of how they have observed their parents/guardians handle conflict or even extended family members like aunts/uncles, grandparents, and cousins.

Holism is often discussed in opposite to reductionism. Reductionists believe that the best way to understand someone’s communicative behavior is to break it down into the simplest parts that make up the system. For example, if a teenager exhibits verbal aggression, a reductionist would explain the verbally aggressive behavior in terms of hormones (specifically testosterone and serotonin). Holistic systems thinkers don’t negate the different parts of the system, but rather like to take a larger view of everything that led to the verbally aggressive behavior. For example, does the teenager mirror their family’s verbally aggressive tendencies? Basically, what other parts of the system are at play when examining a single behavioral outcome.

Patterns/Regularities

Families, like any natural organism, like balance and predictability. To help with this balance and predictability, systems (including family systems) create a complex series of both rules and norms. Rules are dictates that are spelled out. Many children grow up hearing, “children are to be seen and not heard.” This rule dictates that in social situations, children are not supposed to make noise or actively communicate with others. Norms, on the other hand, are patterns of behavior that are arrived at through the system. For example, maybe your mother has a home office, and everyone knows that when she is in her office, she should not be disturbed.

Of course, one of the problems with patterns and regularities is that they become deeply entrenched and are not able to be changed or corrected quickly or easily. When a family is suddenly faced with a crisis event, these patterns and regularities may prevent the family from actively correcting the course. For example, imagine you live in a family where everyone is taught not to talk about the family’s problems with anyone outside the family. If one of the family members starts having problems, the family may try to circle the wagons and ultimately not get the help it needs. This is an example of a situation that happened to one of our coauthors’ families. In this case, one of our coauthor’s cousins became an alcoholic during his teen years. We’ll call him Jesse. Very few people in the immediate family even know about Jesse’s problems. Jesse’s mother was a widely known community leader, so there was a family rule that said, “don’t make mom or our family look bad.” When Jesse’s parents found out about his alcoholism (though a DUI), they circled the wagons and tried to deal with the problem as a family. Unfortunately, dealing with a disease like alcoholism by closing ranks is not the best way to get someone treatment. One night Jesse’s mother was called out to an accident at a local night club where a drunk driver had hit several people. When Jesse’s mother showed up, it was only then that she learned that the drunk driver had been her son.

In this case, the rule about protecting the family’s image had become so ingrained, that the family hadn’t taken all of the steps necessary to get Jesse the help he needed. Although no one died in the accident, one young woman hit by Jesse was paralyzed for the rest of her life. Jesse ended up going to prison for several years.

Interactive Complexity

The notion of interactive complexity stems back to the original work conducted by Murray Bowen on family systems theory. In his initial research looking at schizophrenics, a lot of families labeled the schizophrenic as “the problem” or “the patient,” which allowed them to put the blame for family problems and interactions on the schizophrenic. Instead, Bowen realized that schizophrenia was one person’s diagnosis in a family system where there were usually multiple issues going on. Trying to reduce everything down to the one label, essentially letting everyone else “off the hook” for any blame for family problems, was not an accurate portrayal of the family.

Instead, it’s important to think about interactions as complex and stemming from the system itself. For example, all married couples will have disagreements. Some married couples take these disagreements, and they become highly contentious fights. These fights are often repetitious and seen over and over again. Mary asks Anne to take out the trash. The next day Mary sees that the trash hasn’t been taken out yet. Mary turns to Anne at breakfast and says, “are you ever going to take out the trash?” Anne quickly replies, “Stop nagging me already. I’ll get it done when I get it done.” Before too long, this becomes a fight about Anne not listening to Mary from Mary’s point-of-view, while the conversation becomes about Mary’s constant nagging from Anne’s point-of-view. Before long, the argument devolves into an argument about who started the conflict in the first place. Galvin, Dickson, and Marrow argue that trying to determine who started the conflict is not appropriate from a systems perspective, instead, researchers should focus on “current patterns serves to uncover ongoing complex issues.”31

Openness

The next major characteristic of systems is openness. The term openness refers to how permissive system boundaries are to their external environment. Some families have fairly open boundaries. In essence, these families allow for a constant inflow of information from the external environment and outflow of information to the external environment. Other families are considerably more rigid about system boundaries. For example, maybe a family is deeply religious and does not allow television in the home. Furthermore, the family only allows reading materials that come strictly from their religious sect and actively prevent any ideas that may threaten their religious ideology. In this case, the family has a very rigid and closed boundary. When families close themselves off from the external environment, they essentially isolate themselves. Children who are reared in highly isolated family systems often have problems interacting with other children when they come into contact with them in the external environment (like school). Some families will choose to homeschool their children as another tool to close the family system to foreign ideas and influences.

Complex Relationships

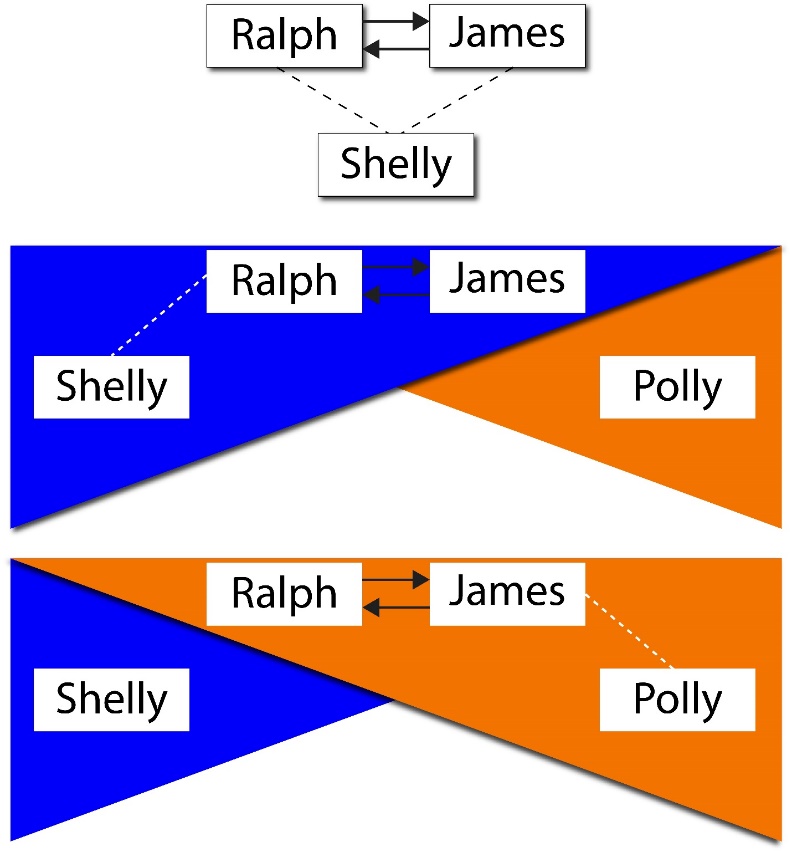

It’s important to remember that all family systems also have multiple subsystems. One of the areas that Murray Bowen became very interested in was how family subsystems develop and function during times of crisis. In Bowen’s view, a couple may be the basic unit within an emotional relationship. Still, any tension between the couple will usually result in one or both parties turning to others. If there are not others within the family itself, partners will bring in external people into the instability. For example, James and Ralph just got married. After a recent argument, Ralph ended up talking to his best friend, Shelly, about the argument (11.4). Bowen argues a two-person system under stress will draw in a third party to provide balance, which ultimately creates a two-helping-one or a two-against-one dynamic. It’s also possible that James decides to talk to his mother, Polly, which creates a different triangle.

Families are filled with relationship triangles. We could describe Ralph and James as parents and Shell and Polly as their daughters just as easily. These triangles are always being created and defined within a family unit when there is instability between two people. During times of crisis, these triangles take on a solution to the instability in the two-person relationship. Unfortunately, this “solution” is either two-helping-one or a two-against-one.32 Basically, in a triangle, there are now two people on one side and one on the other, so it gives a sense of balance. The more family members we start to examine, the more complicated these triangle structures can become.

Equifinality

The final characteristic of family systems is equifinality. Equifinality is defined as the ability to get to the same end result using multiple starting points and paths. Going back to the basic definition of “family” discussed earlier in this chapter, there are many different ways for people to form relationships that are called families. Within family systems theory, the goal is to see how different family systems achieve the same outcomes (whether positive or negative).

Key Takeaways

- Although there are numerous definitions for the term “family,” this book uses the following definition: two or more people tied by marriage, blood, adoption, or choice; living together or apart by choice or circumstance; having interaction within family roles; creating and maintaining a common culture; being characterized by economic cooperation; deciding to have or not to have children, either own or adopted; having boundaries; and claiming mutual affection.

- Family communication patterns include socio-orientation and concept-orientation.

- Murray Bowen’s family systems theory is an extension of Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s general systems theory. Bowen argued that human behavior is not determined by social-construction or intra-psychically generated, but is habitual and rooted in billions of years of evolutionary history.

Marriage Relationships

Earlier in this text, we discussed dating and romantic relationships. For this chapter, we’re going to focus on marriages as a factor of family communication.

Marital Types

One of the most important names in the area of family communication and marital research, in general, is a scholar named Mary Anne Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick was one of the first researchers in the field of communication to devote her career to the study of family communication. Most of her earliest research was all in the area of marriage.57

The Relational Definitions

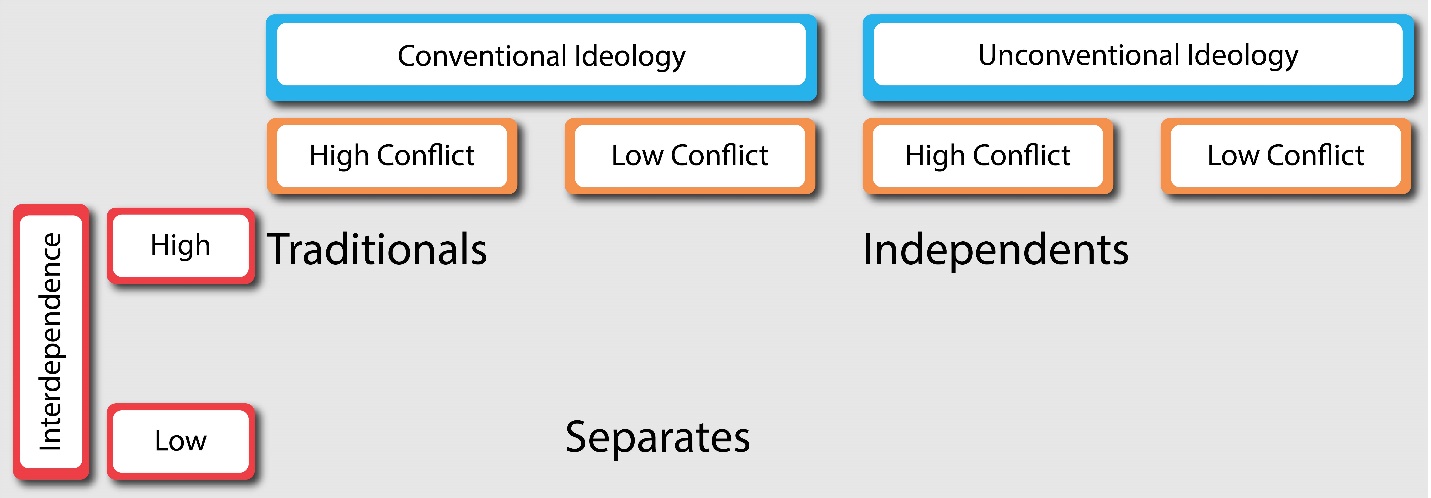

After creating the relational dimensions, Fitzpatrick then further broke this down into a marriage typology that included three specific remarriage types: traditional, independents, and separates.66 Figure 11 illustrates how the three relational definitions were ultimately arrived at.

Traditionals

The first relational definition that Fitzpatrick arrived at was called traditionals. Traditionals are highly interdependent, have a conventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement. First, traditional lives are highly intertwined in both the use of space and time, so they are not likely to feel the need for autonomous space at home or an overabundance of “me time.” Instead, these couples like to be with each other and have a high degree of both sharing and companionship. These couples are more likely to have clear routines that they are happy with. These couples are traditionals also because they do have a conventional ideology. As such, they believe that a woman should take her husband’s name, keep family plans when made, children should be brought up knowing their cultural heritage, and infidelity is never excusable. Lastly, traditionals report openly engaging in conflict, but they do not consider themselves overly assertive in their conflict with each other. Of the three types, people in traditional marriages report the greatest levels of satisfaction.

Independents

The second relational definition that Fitzpatrick described were called independents. Independents have a high level of interdependence, have an unconventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement. The real difference is their unconventional values in what a marriage is and how it functions. Independents, like their traditional counterparts, have high levels of interdependency within their marriages, so there is a high degree of both sharing and companionship reported by these individuals. However, independents tend to need more “me time” and autonomous space. Independents are also less likely to stick with a clear family schedule daily. To these individuals, marriage is something that compliments their way of life and not something that constrains it. Lastly, independents are also likely to openly engage in conflict and report moderate levels of assertiveness and do not avoid conflicts.

Separates

The final relational definition that Fitzpatrick described were called separates. Separates have low interdependence, have a conventional ideology, and low levels of conflict engagement. “Separates seem to hold two opposing ideological views on relationships at the same time. Although a separate is as conventional in marital and family issues as a traditional, they simultaneously support the values upend by independents and stress individual freedom over relational maintenance.”67 Ultimately, these couples tend to focus more on maintaining their individual identity more than relational maintenance. Furthermore, these individuals are also likely to report avoiding conflict within the marriage. These individuals generally report the lowest levels of marriage satisfaction of the three.

Same-Sex Marriages

Up to this point, the majority of the information discussed in this section has been based on research explicitly conducted looking at heterosexual marriages. In one study, Fitzpatrick and her colleagues specifically set out to examine the three relational definitions and their pervasiveness among gay and lesbians.68 Ultimately, the researchers found “gay males, there are approximately the same proportion of traditionals, yet significantly fewer independents and more separates than in the random, heterosexual sample. For lesbians, there were significantly more traditionals, fewer independents, and fewer separates than in the random, heterosexual sample.”69 However, it’s important to note that this specific study was conducted just over 20 years before same-sex marriage became legal in the United States.

The reality is that little research exists thus far on long-term same-sex marriages. The legalization of same-sex marriages in July 2015 started a new period in the examination of same-sex relationships for family and family communication scholars alike.70 As a whole, GLBT families, and marriages more specifically, is an under-researched topic. In a 2016 analysis of a decade of research on family and marriage in the most prominent journals on the subject, researchers found that only .02% of articles published during that time period directly related to LGBTQ families.71 For scholars of interpersonal communication, the lack of literature is also problematic. In an analysis of the Journal of Family Communication, of the 300+ articles published in that journal since its inception in 2001, only nine articles have examined issues related to LGBTQ families. This is an area that future scholars, maybe even you, will decide to study.

Key Takeaways

- Traditional are couples who are highly interdependent, have a conventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement. Independents are couples who have a high level of interdependence, have an unconventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement. Separates are couples who have low interdependence, have a conventional ideology, and low levels of conflict engagement.

- Little research has examined how LGBTQIA couples interact in same-sex marriages. Research has shown that in a decade of research about family and marriage, only .02% articles had to do with LGBTQIA families.

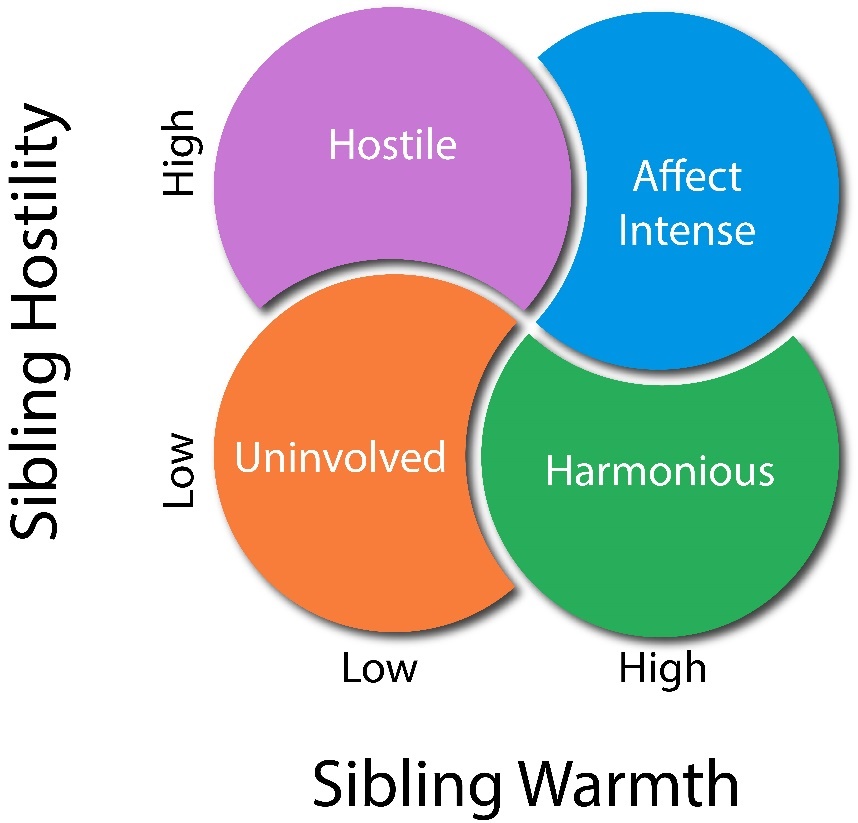

Sibling Types

After examining the literature related to siblings, Shirley McGuire, Susan M. McHale, and Kimberly Updegraff realized that two main concepts were commonly discussed in the literature: hostility and warmth.43 Sibling hostility was characterized by such sibling behaviors as causing trouble, getting into fights, teasing/name-calling, taking things without permission, etc…44 Sibling warmth, on the other hand, was characterized by sibling behaviors such as sharing secrets, helping each other, teaching each other, showing physical affection, sharing possessions, etc…45 Research has shown us that warmth and hostility have an impact on sibling relationships. For example, individuals who have higher levels of sibling warmth are more likely to engage in prosocial behavior.46 Individuals who have sibling relationships that are high in hostility are more likely to report higher levels of aggression, anxiety, depression, and loneliness.47 A recent meta-analysis of sibling relationships found that communicating frequently and feeling close to a sibling is associated with higher well-being and having healthy relationships generally. However, more sibling conflict is related to poor well-being and more negative relationships.33

Sibling Relationship Types

McGuire, McHale, and Updegraff knew that these two dimensions were distinct from one another, so they set out to create a typology of sibling relationships based on hostility (high vs. low) and warmth (high vs. low). You can see this typology in Figure 10.

Harmonious

The first type of sibling relationship is the harmonious relationship. Harmonious sibling relationships are characterized by low levels of hostility and high levels of warmth. In these relationships, the siblings get along very well and have very low levels of problematic conflict. Often siblings in this category get along so well that they are very close friends in addition to being siblings. When it comes to long-term outcomes, harmonious siblings were found to have lower feelings of loneliness and higher self-esteems.48 Research has also found gender effects. When sibling pairs are both female, they are more likely to report harmonious relationships than the other three sibling relationship types. At the same time, the combination of gender and birth-order also makes a difference. Males who are the firstborn are less likely to report harmonious sibling relationships.49

Hostile

The opposite sibling type of the harmonious sibling is the hostile sibling relationship, which is characterized by high levels of hostility and low levels of warmth. These relationships are marked by high levels of conflict between the siblings, which can often be highly physically and verbally aggressive. Furthermore, individuals in hostile sibling relationships are more likely to internalize internalizing of problems along with lower academic success, social competence, and feelings of self-worth.50 These siblings often perceive their siblings as rivals within the family unit, so there is an inherent competition for scarce resources. Often these resources are related to parental attention, respect, and love.

Affect-Intense

The third sibling type is the affect-intense relationship. Affect-intense sibling relationships are marked by both high levels of hostility and warmth. These sibling relationships are as nurturing as harmonious relationships and as dominating as hostile relationships. These relationships are also perceived as more satisfying than hostile sibling relationships.51 In one study examining affect-intense sibling relationships, researchers found that 38% of siblings from divorced families reported their sibling relationships as affect-intense as compared to only 22% of siblings from intact families.

Uninvolved

The last type of sibling relationship is called the uninvolved, which is characterized by low levels of both hostility and warmth. Uninvolved sibling relationships typically don’t have any of the problems associated with affect-intense or hostile sibling relationships. Still, they also do not report any of the benefits that have been found with harmonious sibling relationships.52 Uninvolved sibling relationships also appear to develop later in life. “Perhaps the separation processes and increased focus on peers that begin during adolescence stimulate the development of an uninvolved sibling relationship.”53

Sibling Relationship Maintenance

One area where communication scholars have been instrumental in the field of sibling relationships has been in relationship maintenance, or the communicative behaviors that one engages in to preserve a relationship with another person. In one of the earliest studies to examine sibling relationships in the field, Scott Myers and a group of students explored the relationship between relationship communication and sibling communication satisfaction, liking, and loving.54 Equality, receptivity, immediacy, similarity, and composure were all positively related to communication satisfaction. Composure, equality, similarity, and receptivity were all positively related to sibling liking. Equality, similarity, and receptivity were positively related to loving one’s sibling. The researchers also noted that individuals who perceived their relationships as more formal reported lower levels of loving their siblings. This first study helped pave the way for future research in examining how relationship communication impacts sibling relationships.

In a follow-up study, Scott Myers and Keith Weber set out to construct a measure for analyzing how individuals use communication to maintain their sibling relationships.55 In their research, Myers and Weber found six distinct ways that siblings maintain their relationships through communication: confirmation, humor, social support, family visits, escape, and verbal aggression

Confirmation

The first way that siblings engage in relational maintenances is through confirmation. Confirmation messages help a sibling communicate how much they value the sibling. Sometimes it’s as simple as telling a sibling, “I’m pretty lucky to have a brother/sister like you,” can be a simple way to demonstrate how much someone means to you. These types of messages help validate the other sibling and the relationship.

Humor

A second relational maintenance tool that siblings can use is humor. Being able to laugh with one’s sibling is a great way to enjoy each other’s company. Often siblings find things completely hilarious that outsiders may not understand because of the unique nature of sibling relationships. Siblings also can lovingly make fun of each other. Now, we’re not talking about making fun of someone in a demeaning or mean-spirited manner. For example, one of our coauthors has an older brother who loves to give him a hard time. Recently, our coauthor misspelled something on Facebook, and his brother was right there to point it out and give him a hard time. In some relationships, this could be viewed as criticism, but because of the nature of their relationship, our coauthor knew the incident should be taken in jest.

Social Support

The third way siblings engage in relational maintenances is through social support. Social support is an individual’s perception and the actuality that an individual is loved and cared for and has people they can turn to when assistance or help is needed. Between siblings, this could involve conversations about one’s romantic life or even about parental concerns. Another way that siblings often provide social support is by giving and seeking advice from their sibling(s).

Family Events

The fourth way that families engage in social support is through family events. Now, not all families are big on family events, but some families participate in close-knit gatherings regularly. Some siblings will avoid these events to avoid seeing their other siblings, but many siblings see these opportunities as a way to keep their sibling relationships going. One of our coauthor’s family has problems getting together each year during the holidays because of how busy their schedules are in December. Instead, our coauthor and family go on family trips. Over the years, they’ve gone to Australia, Alaska, Hawaii, The Bahamas, San Francisco, New York City, New Zealand, and many other places. Currently, they’re planning trips to Belize and back to Hawaii. The family looks forward to these vacations together. In addition to these trips, our coauthor’s father also arranges periodic family reunions for his side of the family. Once again, our coauthor and sibling often end up rooming together because both are single. Ultimately, both look forward to these reunions because it gives them a chance to catch up.

Escape

At the same time, it’s often great to attend family events, but we usually only like to attend when we know our sibling will be there. In these cases, we often use our siblings as a form of escape. In fact, some siblings will only attend family get-togethers when they know their sibling(s) will be there. We often have a range of reasons for why we need to escape when we’re interacting with our family, but we are sure glad our sibling(s) are there when we need that escape.

Verbal Aggression

The final relational maintenance strategy that siblings have been found to use is verbal aggression. Now, verbal aggression is generally not viewed as a positive tool for communication. However, some sibling pairs have realized over time that verbally aggressive behavior allows them to get their way or vent their frustrations. However, in the original study by Weber and Myers, the researchers did find that all of the other relational maintenance strategies were positively related to sibling liking, commitment, and trust, but verbal aggression was not.56

Key Takeaways

- Shirley McGuire, Susan M. McHale, and Kimberly Updegraff’s found four sibling relationship types include harmonious, hostile, affect-intense, and uninvolved.

- Siblings generally maintain their relationships using several relational maintenance strategies: confirmation, humor, social support, family visits, escape, and verbal aggression.

Key Terms

concept-orientation

Family communication pattern where freedom of expression is encouraged, and communication is frequent and family life is pleasurable.

family

Two or more people tied by marriage, blood, adoption, or choice; living together or apart by choice or circumstance; having interaction within family roles; creating and maintaining a common culture; being characterized by economic cooperation; deciding to have or not to have children, either own or adopted; having boundaries; and claiming mutual affection.

ideology of traditionalism

Marriages that are marked by a more historically traditional, conservative perspective of marriage.

independents

Marital definition where couples have a high level of interdependence, have an unconventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement.

individuality

Aspect of Murray Bowen’s family system theory that emphasizes that there is a universal, biological life force that propels organisms toward separateness, uniqueness, and distinctiveness.

separates

Marital definition where couples have low interdependence, have conventional ideology, and low levels of conflict engagement.

sibling hostility

Characteristic of sibling relationships where sibling behaviors as causing trouble, getting into fights, teasing/name-calling, taking things without permission, etc…

sibling warmth

Characteristic of sibling relationships where sibling behaviors such as sharing secrets, helping each other, teaching each other, showing physical affection, sharing possessions, etc…

socio-orientation

Family communication pattern where similarity is valued over individuality and self-expression, and harmony is preferred over expression of opinion.

system

Sets of elements standing in interrelation.

togetherness

Aspect of Murray Bowen’s family system theory that emphasizes the complementary, universal, biological life force that propels organisms toward relationship, attachment, and connectedness.

traditionals

Marital definition where couples are highly interdependent, have conventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement

Chapter Wrap-Up

As we discussed at the beginning of this chapter, families are a central part of our lives. Thankfully, several communication scholars have devoted their careers to understanding families. In this chapter, we started by exploring the nature of family relationships with a specific focus on family communication patterns and family systems. Next, we explored the family life cycle. We then discussed the nature of sibling relationships. Lastly, we ended the chapter by discussing marriage.

Notes

Two or more people tied by marriage, blood, adoption, or choice; living together or apart by choice or circumstance; having interaction within family roles; creating and maintaining a common culture; being characterized by economic cooperation; deciding to have or not to have children, either own or adopted; having boundaries; and claiming mutual affection.

Family communication pattern where similarity is valued over individuality and self-expression, and harmony is preferred over expression of opinion.

Family communication pattern where freedom of expression is encouraged, and communication is frequent and family life is pleasurable.

Sets of elements standing in interrelation.

Aspect of Murray Bowen’s family system theory that emphasizes that there is a universal, biological life force that propels organisms toward separateness, uniqueness, and distinctiveness.

Aspect of Murray Bowen’s family system theory that emphasizes the complementary, universal, biological life force that propels organisms toward relationship, attachment, and connectedness.

Marital definition where couples are highly interdependent, conventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement

Marital definition where couples have a high level of interdependence, an unconventional ideology, and high levels of conflict engagement.

Marital definition where couples have low interdependence, conventional ideology, and low levels of conflict engagement.

Characteristic of sibiling relationships where sibling behaviors as causing trouble, getting into fights, teasing/name-calling, taking things without permission, etc.

Characteristic of sibiling relationships where sibling behaviors such as sharing secrets, helping each other, teaching each other, showing physical affection, sharing possessions, etc.