Friendship Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Evaluate friendship characteristics.

- Differentiate among the factors of friendship formation and Rawlins’ seven stages and types of friendship.

- Understand friendships in different contexts.

When you hear the words “friend” or “friendship,” what comes to mind? In today’s society, the words “friend” and “friendship’ can refer to a wide range of different relationships or attachments. We can be a “friend” of a library, museum, opera, theatre, etc.… We can be a “friend” to someone “in need.” We can “friend” thousands of people on social media platforms like Facebook. We can develop friendships with people in our day-to-day lives at work, in social groups, at school, at church, etc.… Some people see their parents/guardians, spouses, and siblings as “friends.” Many of us even have one or more “best friends.” So, when we look at all of these different areas where we use the word “friend,” do we mean the same thing? For this chapter, we’re going to delve into the world of interpersonal friendships.

Beverley Fehr was one of the first scholars to note the problem related to defining the term “friendship,” “Everyone knows what friendship is – until asked to define it. There are virtually as many definitions of friendship as there are social scientists studying the topic.”1 Table 1 presents some sample definitions that exist in the literature for the terms “friend” or “friendship.”

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Anthropological | “A friendship-like relationship is a social relationship in which partners provide support according to their abilities in times of need, and in which this behavior is motivated in part by positive affect between partners.”2 |

| Clinical Psychology | “[S]omeone who likes and wishes to do well for someone else and who believes that these feelings and good intentions are reciprocated by the other party.”3 |

| Dictionary | “The emotions or conduct of friends; the state of being friends.”4 |

| Evolutionary | “Friendship is a long-term, positive relationship that involves cooperation.”5,6 |

| Friendship as Love | “The etymology of word friend connects its meaning with love, freedom and choice, suggesting an ideal definition of friendship as a voluntary relationship that includes a mutual and equal emotional bond, mutual and equal care and goodwill, as well as pleasure.”7 |

| Legal | “Friendship is a word of broad and varied application. It is commonly used to describe the undefinable relationships which exist not only between those connected by ties of kinship or marriage, but as well between strangers in blood, and which vary in degree from the greatest intimacy to an acquaintance more or less casual.”8 |

| Personality | “[V]oluntary, mutual, flexible, and terminable; relationships that emphasize equality and reciprocity, and require from each partner an affective involvement in the total personality of the other.”9 |

| Philosophy | “[A] distinctively personal relationship that is grounded in a concern on the part of each friend for the welfare of the other, for the other’s sake, and that involves some degree of intimacy.”10 |

| Social Psychology | “[V]oluntary or unrestrained interaction in which the participants respond to one another personally, that is, as unique individuals rather than as packages of discrete attributes or mere role occupants.”11 |

Table 1 Defining Friendship

As you can see, there are several different ways that scholars can define the term “friendship.” So, we must question whether defining the term “friendship” is the best way to start a discussion of this topic.

Friendship Relationships

Defining “friend” and “friendship” isn’t an easy thing to do. Many researchers identify characteristics of friendships rather than offer a full definition. We all probably all see our friendships as different or unique, which is one of the reasons why defining the terms is so hard. For our purposes in this chapter, we’re going to go along with the majority of friendship scholars and not provide a strict definition for the term friend.

Friendship Characteristics

William K. Rawlins, a communication scholar and one of the most influential figures in the study of friendship, argues that friendships have five essential characteristics that make them unique from other forms of interpersonal relationships: voluntary, personal, equality, involvement, and affect (Figure 2).13

All Friendships are Essentially Voluntary

There’s an old saying that goes, “You can’t choose your family, but you can choose your friends.” This saying gets at the basic idea that friendship relationships are voluntary. Friendships are based out of an individual’s free will to choose whom they want to initiate a friendship relationship with. We go through our lives constantly making decisions to engage in a friendship with one person and not engage in a friendship with another person. Each and every one of us has our reasons for friendships. For example, one of our coauthors originally established a friendship with a peer during graduate school because they were the two youngest people in the program. In this case, the friendship was initiated because of demographic homophily but continues almost 20 years later because they went on to establish a deeper, more meaningful relationship over time. Take a second and think about your friendships. Why did you decide to engage in those friendships? Of course, the opposite is also true. We meet some people and never end up in friendship with them. Sometimes it’s because you’re not interested, or the other person isn’t interested (voluntariness works both ways). We also choose to end some friendships when they are unhealthy or no longer serve a specific purpose within our lives.

Friendships are Personal Relationships that are Negotiated Between Two Individuals

The second quality of friendships is that they are personal relationships negotiated between two individuals. In other words, we create our friendships with individuals, and we negotiate what those relationships look like with that other individual. For example, let’s imagine you meet a new person named Kris. When you enter into a relationship with Kris, you negotiate what that relationship will look like with Kris. If Kris happens to be someone who is transgendered, you are still entering into a relationship with Kris and not everyone who is transgendered. Kris is not the ambassador for all things transgendered for us, but rather a unique individual we decide we want to be friends with. Hence, these are not group relationships; these are individualized, personal relationships that we establish with another person.

Friendships Have a Spirit of Equality

The next characteristic of friendships is a spirit of equality. “Although friendship may develop between individuals of different status, ability, attractiveness, or age, some facet of the relationship functions as a leveler. Friends tend to emphasize the personal attributes and styles of interaction that make them appear more or less equal to each other.”14 Now, it’s important to note that we’re not always talking about a 50/50 split in everything is what makes a friendship equal. Friendships ebb and flow over time as the desires, needs, and interests change. For example, it’s perfectly possible for two people from very different social classes to be friends. In this case, the different social classes may put people at an imbalance when it comes to financial means, but this doesn’t mean that the two cannot still have a sense of equality within the relationship. Here are some ways to ensure that friendships maintain a spirit of equality:

- Both friend’s needs and desires are important, not just one person’s.

- Both friends are curious about their friend’s personal lives away from the friendship.

- Both friends show affection in their ways.

- Both friends demonstrate effort and work in the relationship.

- Both friends encourage each other’s goals and dreams.

- Both friends are responsible for mutual happiness.

- Both friends decide what activities to pursue and how to have fun.

- Both friends are mutually engaged in conversations.

- Both friends carry each other’s burdens.

- Both friends desire for the relationship to continue and grow.

Friendships Have Mutual Involvement

The fourth characteristic of friendships is that they involve mutual involvement. For friendships to work, both parties have to be mutually engaged in the relationship. Now, this does not mean that friends have to talk on a daily, weekly, or even monthly basis for them to be effective. Many people establish long-term friendships with individuals they don’t get to see more than once a year or even once a decade. For example, my father has a group of friends from high school once a year. His friends and their spouses pick a location, and they all meet up once a year for a week together. For the rest of the year, there are occasional emails and Facebook posts, but they don’t interact much outside of that. However, that once a year get together is enough to keep these long-term (70+ years at this point) friendships healthy and thriving.

As you can see, the concept of “mutual involvement” can differ from one friendship pair to another. Different friendship pairs collaborate to create their sense of what it means to be a friend, their shared social reality of friendship. “This interpersonal reality evolves out of and furthers mutual acceptance and support, trust and confidence, dependability and assistance, and discussion of thoughts and feelings.”15 One of the reasons why defining the term “friendship” is so difficult is because there are as many friendship realities as there are pairs of friends. Although we see common characteristics across them (as we’re discussing here), it’s important to understand that within these characteristics are many ways these get exhibited.

Friendships Have Affective Aspects

The final characteristic of friendships is the notion of affect. Affect refers to “any experience of feeling or emotion, ranging from suffering to elation, from the simplest to the most complex sensations of feeling, and from the most normal to the most pathological emotional reactions. Often described in terms of positive affect or negative affect, both mood and emotion are considered affective states.”16 Built into the voluntariness, personal, equal, and mutually involved nature of friendships is the inherent caring and concern that we establish within those friendships, the affective aspects. Some friends will go so far as to say that they love each other. Not in the eros or romantic sense of the term, but instead in the philia or affectionate sense of the term. People often use the term “platonic” love to describe the love that exists without physical attraction based on the writings of Plato. However, Aristotle, Plato’s student, believed that philia was an even more profound form of dispassionate, virtuous love that existed in the loyalty of friends void of any sexual connotations.

All friendships are going to have affective components, but not all friendships will exhibit or express affect in the same ways. Some friendships may exhibit no physical interaction at all, but this doesn’t mean they are not intimate emotionally, intellectually, or spiritually. Other friendships could be very physically affective, but have little depth to them in other ways. Every pair of friends determines what affect will be like within that friendship pairing. However, both parties within the relationship must have their affect needs met. Hence, people often need to have conversations with friends about their needs for affection.

Dialectical Approaches to Friendships

Earlier in this book, we introduced you to the dialectical perspective for understanding interpersonal relationships. Rawlins proposed a dialectical approach to friendships.22 The dialectics can be broken down into two distinct categories: contextual and interactional.

Contextual Dialectics

The first category of dialectics is contextual dialectics, which are dialectics that stem out of the cultural order where the friendship exists. If the friends in question live in the United States, then the prevailing social order in the United States will impact friendship; however, if the friends are in Malaysia, then the Malaysian culture will be the prevailing social order that impacts the friendship. There are two different dialectics that Rawlins labeled as contextual: private/public and ideal/real.

Private/Public

The first friendship dialectic is the private/public dialectic. Let’s start by examining the public side of friendships in the United States. Sadly, they aren’t given much credence in the public space. For example, there are no laws protecting friendships. Your friends can’t get health benefits from your job. Religious bodies don’t recognize your friendships. As you can see, we’re comparing friendships here to marriages, which do have religious and legal protections. In fact, in the legal system, the family often trumps friends unless there is a power of attorney or will.

As a significant historical side note, one of the biggest problems many gay and lesbian couples faced before marriage legalization was that their intimate partners were perceived as “friends” in the legal system. Family members could swoop in when Partner A passed and evict and confiscate all of Partner A’s money and property unless there was an iron-clad will leaving the money and property to Partner B. From a legal perspective, marriage equality was very important in ensuring the rights of LGBTQIA individuals and their spouses.

On the opposite end of this dialectic, many friendship bonds are as strong if not stronger than familial or marital bonds. We voluntarily enter into friendships and create our sense of purpose and behaviors outside of any religious or legal context. In essence, these friendships are autonomous and outside of social strictures that define the lines of marital bonds. Instead of having a religious organization dictate the morality of a relationship, friendships ultimately develop their sense of morality that is based within the relationship itself.

Ideal/Real

From the moment we are born, we start being socialized into a wide range of relationships. Friendship is one of those relationships. We learn about friendships from our family, schools, media, peers, etc.… With each of these different sources of information, we develop an ideal of what “friendship” should be. However, friendships are not ideals; they are real, functioning relationships that plusses and minuses. This dialectic also impacts how we communicate and interact within the friendship itself. If our culture tells us that people must be reserved and respectful in private, then a simple act of laughing with another person could be an outward sign of friendship.

Interactional Dialectics

It’s important to understand that friendships change over time; along with how we interact within those friendships. For communication scholars, Rawlins interactional dialectics help us understand how communicative behavior happens within friendships.23 Rawlins noted four primary communicative dialectics for friendships: independence/dependence, affection/instrumentality, judgment/acceptance, and expressiveness/protectiveness.

Independence/Dependence

First and foremost, friendships are voluntary relationships that we choose. However, there is a constant pull between the desire to be an independent person and the willingness to depend on one’s friend. We strive for independence in our relationships to feel like an individual. You may do a lot of activities by yourself without a friend. On the other side, we also depend on our friendships. You could have a friend that you do almost everything with, and it gets to the point that people see you as a duo and are shocked when both of you aren’t together. In these highly dependent friendships, individual behavior is probably very infrequent and more likely to be resented. Let’s look at a quick example. It’s a Friday afternoon, and you’re done with class or work. A movie you’ve wanted to see just came out, so you go and watch a matinee. You decided to go alone to the movie (independence). This could be normal for your friendships. Now, if you went to the movie alone in a highly dependent friendship, your friend may be upset or jealous because you didn’t wait to see it with them. Now you may have had the right to engage as an independent person, but a friend in a highly dependent friendship would see this as a violation.

Ultimately, all friendships have to negotiate independence and dependence. As with the establishment of any friendship norm, the pair involved in the relationship needs to decide when it’s appropriate to be independent and when it is appropriate to be dependent. Maybe you need to check-in via text 20 times a day (pretty dependent) or talk on the phone once a year; in both cases, friendships are different and are in constant negotiation. It’s also important to note that a friendship that was once highly dependent can become highly independent and vice versa.

Affection/Instrumentality

The second interaction dialectic examines the intersection of affection as a reason for friendship versus instrumentality (the agency or means by which a person accomplishes their goals or objectives). As Rawlins noted, “This principle formulates the interpenetrated nature of caring for a friend as an end-in-itself and/or as a means to an end.”24 We already discussed the importance of affection in a friendship, but haven’t examined the issue of friendships and instrumentality. In friendships, the issue of instrumentality helps us understand the following question, “How do we use friendships to benefit ourselves?” Some people are uncomfortable with this question and find the idea of instrumentality very anti-friendship. Ever had a really bad day and all you needed was a hug from your best friend? Well, was that hug a sign of affection (maybe), but you used that friendship to get something you wanted/needed. We all do this to varying degrees within friendships. Maybe you don’t have a washer and dryer in your apartment, so you go to your best friend’s place to do laundry. In that situation, you are using your friend and that relationship to achieve a need that you have (wearing clean clothes).

The problem of instrumentality arises when one party feels that they are being used and taken for granted within the friendship itself or if one friend stops seeing these acts as voluntary and starts seeing them as obligatory. First, there are times when there is an imbalance in friendships, and one friend feels that they are being taken advantage of. Maybe the friend with the washer and dryer starts realizing that the only time his “friend” really reaches out to see if he’s available to hang out is when the “friend” needs to do laundry. Second, sometimes acts that were initially voluntary become seen as obligatory. Maybe the friend who needs to wash their clothes starts to see what was once a nice, voluntary gesture as an obligation. If this happens, then the use of the washer and dryer becomes part of the rules of the friendship, which can change the dynamic of the relationship if the person with the washer and dryer isn’t happy about being used in this way.

Judgment/Acceptance

In our friendships, we expect that these relationships are going to enhance our self-esteem and make us feel accepted, cared for, and wanted. On the other hand, interpersonal relationships of all kinds are marked by judgmental messages. Ronald Liang argued that all interpersonal messages are inherently evaluative.25 So, how do we navigate the need to be accepted and the reality of being judged? A lot of this is involved in the negotiation of the friendship itself. Although we may not appreciate receiving criticism from others, Liang argues that criticism demonstrates to another person that we value them enough to judge.26 Now, can criticism become toxic, yes? Maybe you’ve experienced a friend who criticized everything about you. Perhaps it got to the point where it felt that you needed to change pretty much everything about how you look, act, think, feel, and behave just to be “good enough” for your friend. If that’s the case, then that friend is clearly not criticizing you for your betterment but for their desires.

Expressiveness/Protectiveness

The final interactional dialectic is expressiveness/protectiveness. This dialectic questions the degree to which we want to express ourselves in our friendships while also protecting ourselves. As we discussed earlier in this book, social penetration theory starts with the basic idea that in our initial interactions with others we disclose a wide breadth about ourselves. Still, these are primarily surface level topics (e.g., what’s your major, what are your hobbies, where are you from, etc.). As time goes on, the number of topics we express decreases, but they become more personal (depth). In a friendship relationship, we have to navigate this breadth and depth in deciding what we express and what we protect.

Ultimately, this is an issue of vulnerability. When we open ourselves up to people and express those deeper parts of ourselves, there is an excellent likelihood that disclosure of these areas could cause greater harm to the individual self-disclosing if the information got out. For example, if a friend disclosed their sexual orientation with you, and you share that with their parents, it could violate the confidentiality they expected. All friendships are an exploration of what can be expressed and what needs to be protected. We all have some friends that we keep at arm’s length because we know we need to protect ourselves because they tend to gossip. At the same time, we have other friends who get to see the real us as we protect less and less of ourselves in those friendships. No one will ever completely know what’s going on in our heads, but deep friendships probably come the closest and also make us the most vulnerable.

Key Takeaways

- Rawlins proposed five specific characteristics of friendships: voluntary, personal, equality, involvement, and affect.

- Rawlins’ dialectical approach to communication breaks friendship down into two large categories of dialectical tensions: contextual (private/public & ideal/real) and interactional (independence/dependence, affection/instrumentality, judgment/acceptance, and expressiveness/protectiveness).

Stages and Types of Friendships

In Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s musical “Merrily We Roll Along,” the story follows the careers and friendships of three people trying to make in New York City. One song in the show has always stuck out because of its insightful message about friendship, “Hey Old Friends.” In the musical, three friends Mary, Charlie, and Frank get together after not having seen each other for a while. The purpose of the song is to discuss how some friendships can persist even when we aren’t in each other’s lives daily. You can see a clip from the rehearsal at the New York City Center’s Encore’s production starring Celia Keenan-Bolger (Mary), Colin Donnell (Frank) and Lin-Manuel Miranda (Charley). In this short song, we learn a lot about the nature of this group’s friendship and their enduring desire to be close to one another through the ins and outs of life.

Friendship Formation

Researcher Beverley Fehr studied how friendships are initiated. Fehr found many factors that impact the possibility for two people to become friends; these include environmental, situational, individual, and dyadic factors.27 Enviornmental factors relate to the proximity and physical distance between individuals. The closer two people live near each other, the more likely they will become friends. In residence halls, having a room closer to someone increases the probability of becoming friends. If the environmental factors are not right, a friendship is unlikely to form.

Situational factors include the probability of future interactions, the frequency of interacting, and availability. If you think you’ll never see this person again, then you likely not try to form a friendship. If you interact with a person regularly, research suggests that you’ll start to like them more. The final situational factor is availability. Even though you may see someone regularly and will in the future, you may not become friends. Both people must be ready and able to start a new friendship. Some may have lots of relationships already and may not have the time to invest in a new one. Beyond the situational factors, there are still individual and dyadic considerations.

Individual factors help people to determine how to exclude or include potential friends. There are many reasons why you may decide you don’t want someone to be your friend, including personality characteristics, habits, and attributes. Fehr found that the main reasons to include a friend are their physical attractiveness, social skills, and responsiveness. Physical attractiveness and social skills are desirable attributes. Researchers have found that people who are more responsive appear more interested and likable.

Finally, dyadic factors consider the interplay between each person in the potential friendship. Friendships should have reciprocal liking, meaning that both individuals should like each other. Friendships also need self-disclosure. As we have discussed in earlier chapters, self-disclosure can increase our ability to be liked and how much we like others. Other dyadic factors include sharing humor and fun times. The last dyadic factor is similarity. Individuals are more likely to become friends with those they are similar to.28

There are multiple factors that impact the chance that a friendship will form. Environmentally, your proximity to another person plays a large role in becoming friends. Situationally, both people must think they can invest in a new friend. Individually, people have criteria for who they would and would not want to be friends with. Dyadically, the interactions between both matters.

Stages of Friendships

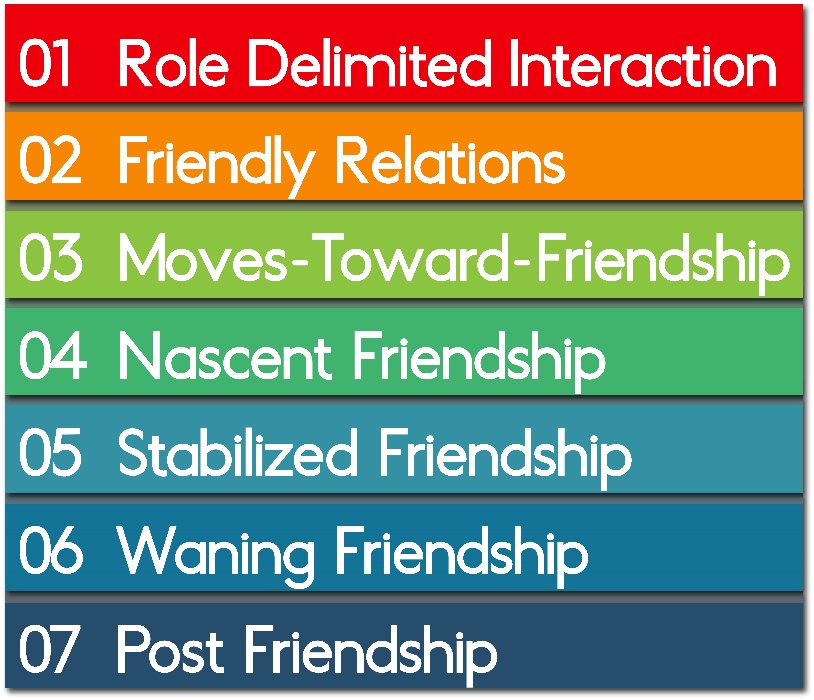

As we’ve already discussed, friendships are not static relationships we’re born with. Instead, these relationships are dynamic, and we grow with them. To help us understand how we ultimately form friendships, William Rawlins broke this process into seven stages of friendships (Figure 3).29

Role Delimited Interaction

The first stage of friendship is called role delimited interaction. The basic idea behind this stage is that we all exist in a wide range of roles within our lives: shopper, salesperson, patient, driver, student, parent/guardian, spouse, etc.… In each of these different roles, we end up interacting with a wide range of different people. For example, imagine you’re just sitting down in a new class in college, and you talk to the stranger sitting next to you named Adilah. In this case, you are both interacting within your roles as students. Outside of those roles and that context, you may never meet and never have the opportunity even to develop a social relationship with this other person. This does not discount the possibility of random, chance encounters with other people. Still, most of our interpersonal relationships (outside of our family) stem from these roles and the communicative contexts they present.

Friendly Relations

From role delimited interaction, we may decide to move to the second stage of friendship, friendly relations. These relations are generally positive interactions, but they still exist within those same roles. In our example, we start chatting with Adilah before the beginning of each class. At this point, though, most of our interactions are still going to be within those roles, so we end up talking about the class, fellow students, the teacher, homework assignments, etc.… Notice that there is not a lot of actual self-disclosure happening within friendly relations. Some people can maintain friendly relations with others for years. For example, you may interact with coworkers, religious association members, neighbors within this type of relationship without them ever progressing to the next stage of friendship. According to Rawlins, friendly relationships move towards friendships because they start to exhibit four specific communication behaviors:

- moves away from what is required in the specific role relationship,

- fewer lines and less stereotyped interaction,

- individual violations of public propriety, and

- greater spontaneity.30

First, we start interacting in a manner that doesn’t resemble the original roles we had. In our example, we start interacting in a manner that doesn’t resemble the roles of students when they first meet. Second, we move away from lines of communication that are stereotypes for our roles. For example, some possible stereotyped lines for two students could include, “what did you think of the homework;” “did you bring your book with you today;” “see you next class;” etc… In each of these lines, we enact dialogue that is expected (or stereotyped) within the context of the class itself. Third, more of our normal selves will start to seep into our interactions, which are called violations of public propriety. Maybe one day Adilah turns to you before class, saying, “That reading for homework was such a waste of time.” In this case, Adilah is giving you a bit more insight into who she is as a person. “These violations of public propriety single an individual out as having an essential side which is not so easily circumscribed by the protocol of a situation.”31 Lastly, we see increased spontaneity in our interactions with the other person. Over time, these interactions, although still interacting within their formal roles, take on more social and less formalized tones. Maybe one day Adilah tells you a joke or shares a piece of gossip she heard. In this case, Adilah she’s starting to be more spontaneous and less structured in her interactions with us.

Moves-Toward-Friendship

At some point, people decide to interact with one another outside of the roles they originally embodied when they initially met. This change in roles is a voluntary change. In our example, maybe one day Adilah invites you to get coffee after class, and then another day, you ask her to get lunch before class. Although it’s possible that a single step outside of those roles could be enough that a friendly relation is moving towards a friendship, there is generally a sequence of these occurrences. In our example here, Adilah may have made the first move inviting us to coffee, but we then reciprocated later by asking her to lunch. In both of these cases, we are starting to step outside of the original friendly relation and changing the nature of our original interactions.

Nascent Friendship

When one enters into the nascent stage of friendship, the friends are no longer interacting within their original roles, and their interactions do follow the stereotypes associated with those roles. Eventually, we start to develop norms for how we communicate with this other person that is beyond those original roles and stereotypes. Ultimately, this stage is all about developing those norms. We develop norms for what we talk about, when we talk, and how we talk. Maybe Adilah makes it very clear that she doesn’t want to talk about politics or religion, and we’re perfectly OK with that. Maybe we keep the bulk of our interaction before and after class, or we start having lunch together before class or coffee after class. The norms will differ from friendship to friendship, but these norms allow us to set parameters on the relationship in this early stage. These norms are also important because keeping them demonstrates that we can be trusted. And when we show we can be trusted over time, the level of intimacy we can develop within our relationship also increases.

It’s also during this period that others start to see you more and more as a pair of friends, so other; external forces may begin to impact the development of your friendship as well. In our case, maybe Adilah has a sister who also goes to the school, so she starts hanging out with both of you from time to time. Maybe we have a significant other, and they start hanging out as well. Even though we may have these distractions, we should keep faithful to the original friendship. For example, if we start spending more time with Adilah’s sister than Adilah, then we aren’t faithful to the original friendship. Lastly, our friendship crystalizes, and others start to see you as a pair. You are seen increasingly as a “duo.”

Stabilized Friendship

Ultimately nascent friendships evolve into stabilized friendships through time and refinement. It’s not like one day you wake up and go, “My friendship has stabilized!” It’s much more gradual than that. We get to the point where our developed norms and interaction patterns for the friendship are functioning optimally for both parties, and the friendship is working smoothly. In nascent friendships, the focus is on the duo and developing the friendship. In stabilization, we often bring in new friends. For example, if we had found out that Adilah had coffee with another person from our class during the nascent stage of friendship, we may have felt a bit hurt or jealous by this “outsider” intruding on our growing friendship.” As stabilized friends, we realize that Adilah having coffee with someone else isn’t going to impact the strength of the relationship we already have. If anything, maybe Adilah will find other friends to grow the friendship circle. However, like any relationship, both parties still must make an effort to make the friendship work. We need to reaffirm our friendships, spend time with our friends, and maintain that balance of equity we discussed earlier in this chapter).

Rawlins also notes that friendships in the stabilized stage can represent three different basic patterns: active, dormant, and commemorative.32 Active friendships are ones where there is a negotiated sense of mutual accessibility and availability for both parties in the friendship. Dormant friendships “share either a valued history or a sufficient amount of sustained contact to anticipate or remain eligible for a resumption of the friendship at any time.”33 These friends may not be ones we interact with every day, but they are still very much alive and could take on new meaning and grow back into an active friendship if the time arises. And commemorative friendships are ones that reflect a specific space and time in our lives, but current interaction is minimal and primarily reflects a time when the two friends were highly involved in each other’s lives. With commemorative friendships, we still see ourselves as friends even though we don’t have the consistent interaction that active friendships have.

In a study conducted by Sara LaBelle and Scott Myers, the researchers set out to determine what types of relational maintenance strategies do people use to keep their friendships going across the three different types of friendship patterns (active, dormant, & commemorative).34 Using the seven relational maintenance behaviors (positivity, understanding, self-disclosure, relationship talks, assurances, tasks, & networks),35 the researchers recruited participants over the age of 30 to examine relational maintenance and friendship types. All three friendship types used positivity, relational talks, and networks to some degree. However, active friendships were more likely to use understanding, self-disclosure, assurances, and tasks to maintain their friendships than commemorative friendships.

Waning Friendship

Unfortunately, some friendships will not last. There are many reasons why friendships may start to wane or decrease in importance in our lives. There are three primary reasons Rawlins discusses why this happens: “an overall decline in affect, an individual or mutual decision to let it wane based on identifiable dissatisfaction with the relationship, or a significant, negative, relational event which precipitates an abrupt termination of the friendship.”36 First, some relationships wane because there is a decrease in emotional attachment. Some friends stop putting in the time and effort to keep the friendship going, so it’s not surprising that there is a decrease in emotional attachments. Second, both parties may become dissatisfied with the relationship and decide to take a hiatus or spend more time with other friends. Lastly, something could happen, a relationship destroying event. You find out that Adilah had an affair with your romantic partner. Adilah broke a promise to you or told someone one of your secrets. Adilah started yelling at you for no reason and physically assaulted you.

There is a wide range of different events that could end a friendship. In a study conducted by a team of researchers led by Amy Janan Johnson, the researchers interviewed college students about why their friendships had terminated.37 The most common reasons listed for why relationships fell apart were 1) romantic partner of self or friend, 2) increase in geographic distance, 3) conflict, 4) not many common interests, 5) hanging out with different groups or different friends, and 5) other. Now, females and males in the study did report differences in the likelihood that these five reasons led to deterioration. Females reported that conflict was a greater reason for friendship deterioration than males. And males reported not having many common interests was a greater reason for friendship deterioration than females. Females and males did not differ in the other three categories. It’s important to note, that while this set of findings is interesting, it was conducted using college students, so it may not apply to older adults.

Post-Friendship

The final stage of the friendship is what happens after the friendship is over. Even if a friendship ended on a horrible note, there are still parts of that friendship that will remain with us forever. That friendship will impact how we interact with friends and perceive friendships forever. You may even have symbolic links to your friends: the nightclubs you went to, the courses you took together, the coffee shops you frequented, the movies you watched, etc.… all are links back to that friendship. It’s also possible that the friendship ended on a positive note and you still periodically say hello on Facebook or during the holidays through card exchanges. Just as all friendships are unique, so are their experiences of post-friendship reality.

Research Spotlight

In 2019, KU’s Jeffrey Hall was interested in the amount of time it took for people to become friends.17 Through two studies, the first consisting of adults who recently relocated to a new geographic location, and the second, a longitudinal study of first-year college students, Hall found the amount of time spent together in hours was related to friendship closeness.

Depending on how much time passes between meeting a person, there is approximately a 50% chance of transitioning into a new category for each friendship type.

- Acquaintances to casual friends: 40-60 hours

- Casual friends to friends: 80-100 hours

- Friends to good/best friends: 120-160 hours

Talking regularly with friends and spending time doing leisurely activity also predicted friendship closeness. Hall found that it takes many hours for a friendship to develop, and even more time for two people to become close friends.

Hall, J. A. (2019). How many hours does it take to make a friend? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(4), 1278-1296. doi:10.1177/0265407518761225

Types of Friendships

Rawlins also created 3 types of friendships.73 These include active, dormant, and commemorative. Active friendships can be thought of as the close friendships you currently have. These are friends you communicate with regularly and know what is going on in each other’s lives. Dormant friendships are relationships that you may have fallen out of touch with. However, with dormant friends, you could send a message or call to pick up where you left off. Think of these as friends you used to be close with but haven’t spoken to recently. Commemorative friends are past friendships that you no longer maintain or think about. These are your friends from the past who you are unlikely to ever speak to again. In the era of social media however, these friendship types may feel a bit different. Dr. Natalie Pennington, who received their Ph.D. from KU, recently conducted a study about these friendships over social media. Pennington found that people keep dormant and commemorative friendships on social media for “potential reconnection, perceived social capital, and nostalgia.”74These three types of friendships can help us understand our current and past relationships.

Good and Bad Friendships

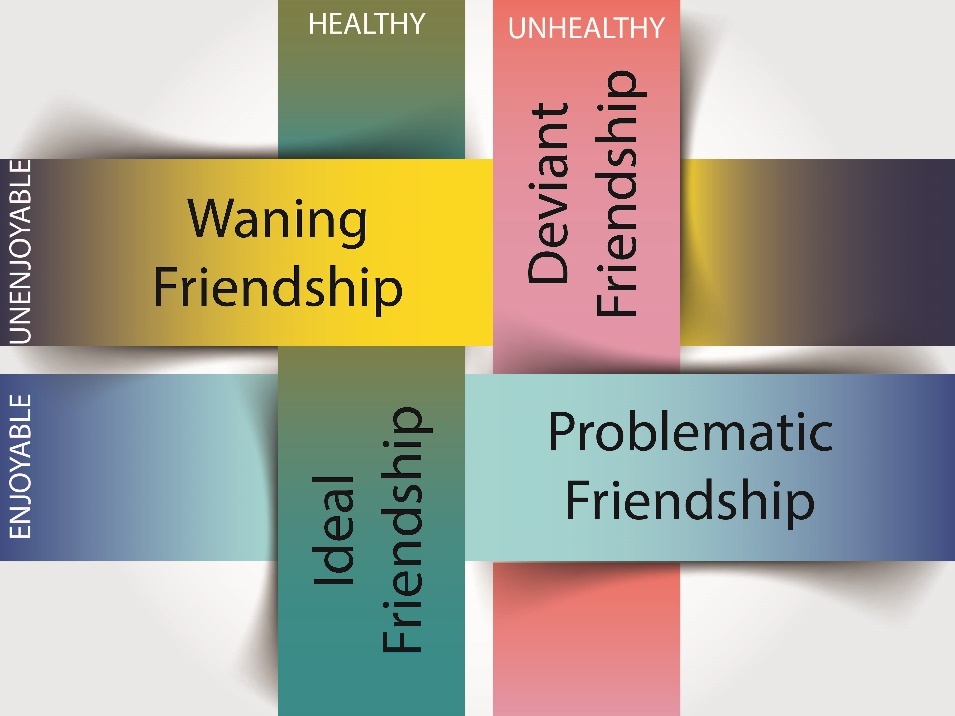

Another system for understanding friendships is to think of them regarding two basic psychological constructs: health and enjoyment. First, is the relationship a healthy one for you to have. Although this is a concept that is more commonly discussed in romantic relationships, friendships can also be healthy or nonhealthy (Table 2).

| Healthy | Unhealthy |

|---|---|

| Mutual respect | Contempt |

| Trust | Suspicion |

| Honesty | Untruthful |

| Support | Hinder |

| Fairness/Equality | Unjust/Inequity |

| Separate Identities | Intertwined Identities |

| Open Communication | Closed Communication |

| Playfulness/Fondness | Sober/Animus |

| Self-Esteem Enhancing | Self-Esteem Destroying |

| Fulfilling | Depressing |

| Acceptance | Combative |

| Affectionate/Loving | Cold/Indifferent |

| Comforting | Stressful |

| Genuine/Benevolent | Manipulative/Exploitive |

| Beneficial | Damaging |

| Healthful | Toxic |

Table 2 Healthy vs. Unhealthy Friendships

In addition to the health of a friendship, you must also question if the friendship is something that is ultimately enjoyable to you as a person. Does this friendship give you meaning of some kind? Ultimately, we can break this down into four distinct types of friendship experiences people may have (Figure 5).

Ideal Friendship

The first category we label as “ideal friends” because these relationships are both healthy and enjoyable. In an ideal world, the majority of our relationships would fall into the category of ideal friendships.

Waning Friendship

The second category we label as “waning friendship” because these friendships are still healthy but not enjoyable anymore. Chances are, this friendship was an ideal friendship at some point and has started to become less enjoyable over time. There’s a wide range of reasons why friendships may stop being enjoyable. It’s possible that you no longer have the time to invest in the friendship, so you find yourself regretting the amount of time and energy that’s necessary to keep the friendship floating.

Problematic Friendship

The third category of friendship, which we classify as problematic friendships, is tricky because these are enjoyable, but they are not healthy for us. Ultimately, the friend we have could be a lot of fun to hang out with, but they also could be more damaging to us as people. Instead of supporting us, they make fun of us. Instead of treating us as equals, they hold all the power in the relationship. Instead of being honest, we always know they’re lying to us. Ultimately, we must question why we decide to stay in these relationships.

Deviant Friendship

The final category of friendships we may have is deviant friendships, more commonly referred to as toxic friendships. For our purposes here, we use the term “deviant” because it refers to any behavior that violates behavioral norms. In this case, any friendship situation that is clearly outside the parameters of what is a healthy and enjoyable friendship is not the norm. Unfortunately, sometimes people get so stuck in these friendships that they stop realizing that these friendships aren’t normal at all. Others may think that their deviant friendships are the only kinds of friendships they can get and/or deserve. It’s entirely possible that a deviant friendship started as perfectly healthy and normal, but often these were somewhat problematic in their early stages and eventually progressed into fully deviant friendships.

Deviant Friends:

- Use criticism and insults as weapons.

- Use guilt to get you to cave-in to their desires and whims.

- Immediately assume you’re lying (probably because they are).

- Disclose your personal secrets.

- Are very gossipy about others, and are probably gossipy about you as well.

- Only care about their own desires and needs.

- Use your emotions as weapons to attack you psychologically.

- Pass judgment on you and your ideas based on their own with little flexibility.

- Are stuck up and only really turn to you when they need you.

- Can be obsessively needy, but then are very hard to please.

- Are inconsistent, so predicting how they will think or behave can be very hard if not impossible.

- Put you in competition with their other friends for affection and attention.

- Conversations tend to be all about them and their desires and needs.

- Make you feel that being your friend is a chore for them.

- Make you feel as if you’ve lost control over your own life and choices.

- Cross major relationship boundaries and violate relationship norms without apology.

- Express their jealousy of your other friendships and relationships.

Friendships in Different Contexts

So far in this chapter, we’ve explored the foundational building blocks for understanding friendships. We’re now going to break friendships down by looking at them in several different contexts: gender and friendships and cross-group friendships.

Gender and Friendships

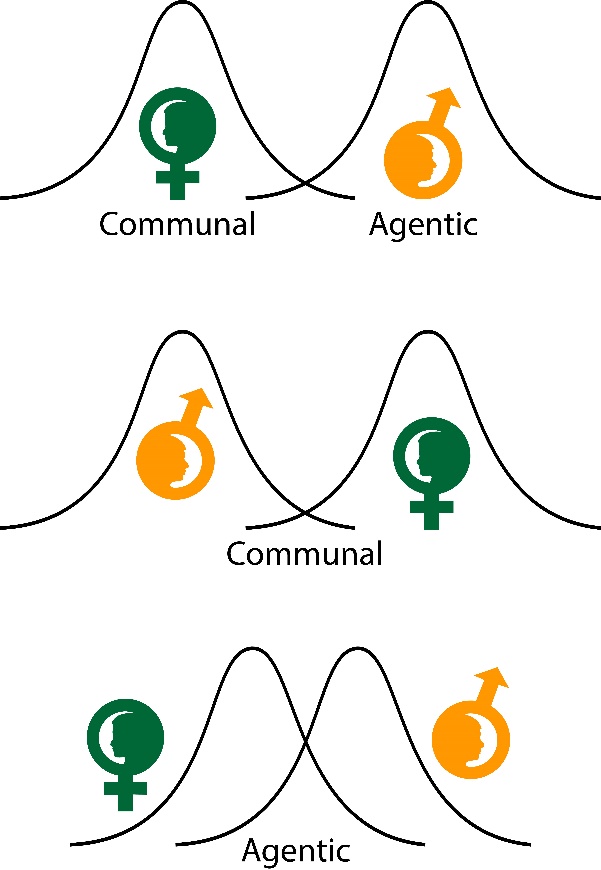

From a highly traditional perspective on the notion of same and opposite sex friendships, researchers generally compared notions of communal and agentic friendships. Communal friendships were marked by intimacy, personal/emotional expressiveness, amount of self-disclosure, quality of self-disclosure, confiding, and emotional supportiveness.42 Agentic friendships, on the other hand, were activity-centered. If you look at Figure 6, you’ll see three curves associated with these concepts. The first one shows women being communal and men being agentic in their friendships, which was a common perspective on the nature of gender differences and friendships. In reality, research demonstrated that both males and females can have communal relationships even though women report notedly higher levels of communality in their friendships (second set of curves). As for agency, women and men were found to both have agentic friendships, and there was considerable overlap between the two groups here, with men being slightly more agentic (seen in the third set of curves).

A great deal of research in friendship has focused on sex differences between males and females with regard to friendship. In this section, we’re going to start by looking at some of the research specifics to same-sex friends and then opposite sex friendships. We’ll end this section discussing a different way of thinking about these types of relationships.

Same-Sex Friendships

For a lot of research, we use the term “same-sex” to refer to two individuals of the same biological sex as friends. Gerald Phillips and Julia Wood argue that there are four primary reasons females develop friendships with the same-sex: activities, personal support, problem-solving, and reciprocation.43 However, these four categories are different, whether looking at female or male friendships. For female same-sex friendships, the first reason is activity. These are friendships that tend to develop around a specific activity: working out, church, social clubs, etc.… For the most part, these friendships stay confined to the activity itself and provide a chance for conversation and noncommittal associations. The second reason is personal support. It’s this second category that many highlight when discussing the differences between female and male friendships. Personal support involves friendships where an individual has a personal confidant with whom they can share their deepest, darkest secrets, concerns, needs, and desires. These friendships are often highly stable friendships and tend to last for a long time. By nature, these friendships tend to be highly communal, which is why we generally discuss them as a key reason for female same-sex friendships. Third, all of us have areas where we’re skillful and lack skill. We often develop friendships with people who have skills that are complementary to our own. Consciously or subconsciously, we develop friendships with others out of a need to problem solve our daily lives. For example, an information technology specialist may become friends with an accountant. In their friendship, they provide complementary support: computer help and financial advice. Finally, females tend to view their friendships as highly reciprocal. They expect to get out of a friendship what they put into a friendship; it’s a mutual exchange. If a female feels her friend is not putting into a relationship the same amount of time and energy, she is less likely to keep sustaining that friendship.

As for male-male friendships, research shows us that they’re not drastically different though their friendships may be framed differently. They still create friendships because of recreation, personal support, problem-solving, and reciprocation. And these relationships can be just as intimate as their female counterparts, but the relationships may look a bit more distinct. First, many male friendships are based around activities: church, work, hobbies, social clubs, etc.… These friendships are less about having conversations and more about engaging in the activity at hand. These friendships are not going to be as communal as female friendships that develop around recreation. Often people mistake these male friendships as being less “intimate” because they do not disclose a lot of information, and there isn’t necessarily a lot of talk involved, but males do find these relationships perfectly fulfilling.

Phillips and Woods noted that men often view friendships in terms of teams; you have allies and team members. In essence, they create their tight-knit circles of in and out-group members based on “team” status. Part of this team status involves performing favors for each other and siding with one another. It’s the whole “I’ve got your back” mentality. We should also note that males are more likely to be friends who are the most like them: similar majors, similar religious, similar rungs of the social hierarchy, similar socioeconomic status, similar attitudes, similar interests, etc.… Research has even shown that males are more likely to have male friends who are equally physically attractive.44 One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that males are more likely to develop relationships based on social hierarchies. If attractive males are on a higher rung of a social hierarchy, then it’s not surprising that the matching effect occurs.45 It should be noted that the expectations of same-sex friendships are mostly the same for males and females. Both expect their friends to be trustworthy, loyal, genuine, and committed to the friendship.18 Further, research has shown that there is more overlap between female-female and male-male friendships than there are actual differences.

Opposite Sex Friendships

“Friendship between a woman and a man? For many people, the idea is charming but improbable.”46 William Rawlins originally wrote this sentence in 1993 at the start of a chapter about the problems associated with opposite sex or cross-sex friendships. What do you think? J. Donald O’Meara discusses five distinct challenges that cross-sex relationships have: emotional bond, sexuality, inequality and power, public relationships, and opportunity structure.47,48

Emotional Bond

First, and foremost, in Western society females and males are raised to see the opposite sex as potential romantic partners and not friends. One of the inherent problems with cross-sex friendships is that one of the friends may misinterpret the friendship as romantic. From an emotional sense, the question that must be answered is how do friends develop a deep-emotional or even loving relationship with someone of the opposite sex. William Rawlins did attempt to differentiate between five distinct love styles that could help distinguish the types of emotional bonds possible: friendship, Platonic love, friendship love, physical love, and romantic love.49 O’Meara correctly surmises that the challenge for cross-sex friendships is finding that shared sense of love without one partner slipping into one of the other four categories of love because often the emotions associated with all five different types of love can be perceived similarly.

Sexuality

As the obvious next step in the progression of issues related to cross-sex friendships is sexuality. Inherent in any cross-sex friendship between heterosexual couples is sexual attraction. Sexual attraction may not be something initial in a relationship. Still, it could develop further down the line and start to blur the lines between someone’s desire for friendship and a sexual relationship. In heterosexual cross-sex friendship, it is possible for latent or manifested sexual attraction. Even if one of the parties involved in the friendship is completely unattracted to the other person, it doesn’t mean that the other friend isn’t sexually attracted. As such, like it or not, there will always be the issue of sexuality in cross-sex friendships once people hit puberty. Now it’s perfectly possible that both parties within a friendship are mutually sexually attracted to each other and decide openly not to explore that path. You can find someone sexually attractive and not see them as a viable sexual or romantic partner. For example, maybe you both decide not to consider each other viable sexual or romantic partners because you’re already in healthy romantic relationships, or you may realize that your friendship is more important.

Inequality and Power

We live in a society where men and women are not treated equally. As such, there will always be a fact of inequality and power-imbalance between people in cross-sex friendships created by our society. Females are more likely to get their emotional needs through same-sex friendships. However, males are also more likely to get their emotional needs met through opposite sex friendships. This dependence on the opposite sex for emotional needs and support places females in a subordinate position of needing to fulfill those needs.

Public Relationships

The next challenge for cross-sex friendships involves the public side of friendships. The previous three challenges were all about the private inner workings of the friendship between a female and a male (internal side). This challenge is focused on public displays of cross-sex friendships. First, it’s possible that others will see a cross-sex friendship as a romantic relationship. Although not a horrible thing, this could give others the impression that a pair of friends are not available for romantic relationships. Or if one of the friends is seen on a date, that the friend is clearly cheating on their significant other. Second, it’s possible that others won’t believe the couple as “simply being friends.” This consistent devaluing of cross-sex friendships and the favoring of cross-sex romantic relationships in our society puts a lot of stress on cross-sex friendships. This devaluating of friendships over romantic relationships can also be seen as a tool to delegitimize cross-sex friendships. Third, it’s possible that others may question the sexual orientation of the individual’s involvement in the opposite sex friendship. If a male is in a friendship relationship with a female, he may be labeled as gay or bisexual for not turning that cross-sex friendship into a romantic one. The opposite is also true. Lastly, public cross-sex friendships can cause problems for cross-sex romantic partners. Although not always the case, it may be very difficult for one member of a romantic relationship to conceive that their partner is in a close friendship relationship with the opposite sex that is not romantic or sexual. For individuals who have never experienced these types of emotional connections, they may assume that it is impossible and that the cross-sex friends are just “kidding themselves.” Another possible problem for romantic relationships is that the significant other becomes jealous of the cross-sex friend because they believe that, as the significant other, they should be fulfilling any role a cross-sex friend is.

Postmodern Friendships

In the previous section, we looked at some of the basic issues of same-sex and cross-sex friendships; however, a great deal of this line of thinking has been biased by heteronormative patterns of understanding.52 The noted absence of LGBTQIA individuals from a lot of the friendship literature is nothing new.53 However, we have needed newer theoretical lenses to help us break free of some of these historical understandings of friendship. “Growing out of poststructuralism, feminism, and gay and lesbian studies, queer theory has been favored by those scholars for whom the heteronormative aspects of everyday life are troubling, in how they condition and govern the possibilities for individuals to build meaningful identities and selves.”54 By taking a purely heteronormative stance at understanding friendships, friendships scholars built a field around basic assumptions about gender and the nature of gender.55

Monsour, a friendship researcher, asked a group of friendship scholars about the definition of “friendship” and found there was little to no consensus. How then, Monsour argues, can researchers be as clear in their attempts to define “gender” and “sex” when analyzing same-sex or opposite sex friendships.56 As part of his discussion questioning the nature of gender and sex and how it’s been used by friendship scholars, Monsour provided the following questions for us to consider:

- What does it mean to state that two individuals are in a same-sex or opposite sex friendship and/or that they are of the same or opposite sex from one another?

- What decision rules are invoked when deciding whether a particular friendship is one or the other?

- Why must the friendship be one or the other?

- If friendship scholars and researchers believe that all friendships are either same–sex or opposite–sex (and it appears that most do), at a minimum there should be agreement about what constitutes biological sex. What biological traits make a person a female or a male?

- Are they absolute?

- Are they universal?57

- As part of this discussion, Monsour provides an extensive list of areas of controversy related to the terms used for binary gender identity.

- What about individuals who are intersexed?

- What about individuals with chromosomal differences outside of traditional XX and XY (e.g., X, Y, XYY, XXX, XXY, etc.)? Heck, there are even some XXmales and XYfemales who develop because of chromosomal structural anomalies SRY region on the Y chromosome.

- What about bisexual, gay, and lesbian people?

- What about people who are transgendered or transsexual?

- What about people who are asexual?

Hopefully, you’re beginning to see that the concept of ascribing same-sex and opposite sex friendships simply based on 46-chromosomal pairs of either XX or XY who are cisgendered and heterosexual may not be the best or most complete way of understanding friendships.

We should also note that research in the field of communication has noted that an individual’s biological sex contributes to maybe 1% of the differences between “females” and “males.”58 So, why would we use the words “same” and “opposite” to differentiate friendship lines when there is more similarity between groups than not? As such, we agree with the definition and conceptualization of the term created by Mike Monsour and William Rawlins’ “postmodern friendships.”59 A postmodern friendship is one where the “participants co-construct the individual and dyadic realities within specific friendships. This co-construction involves negotiating and affirming (or not) identities and intersubjectively creating relational and personal realities through communication.”60 Ultimately, this perspective allows individuals to create their own friendship identities that may or may not be based on any sense of traditional gender identities.

Cross-Group Friendships

Social identity theory Social Identity Theory is applicable to cross-group friendships.19 As we noted above, research has found that one of the biggest factors in friendship creation is the groups one belongs too (more so for males than females). In this section, we’re going to explore issues related to cross-group friendships. A cross-group friendship is a friendship that exists between two individuals who belong to two or more different cultural groups (e.g., ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, nationality, etc.). “The phrase, ‘Some of my best friends are…’ is all too typically used by individuals wanting to demonstrate their liberal credentials. ‘Some of my best friends are… gay.’ ‘Some of my best friends are… Black.’ People say, ‘Some of my best friends are…’ and then fill in the blank with whatever marginalized group which they care to exonerate themselves.”61 Often when we hear people make these “Some of my best friends are…” statements, we view them as seriously suspect and question the validity of these relationships as actual “friendships.” However, many people develop successful cross-group friendships.

It’s important to understand that our cultural identities can help us feel that we are part of the “in-group” or part of the “out-group” as well. Identity in our society is often highly intertwined with marginalization. As noted earlier, we also know that males are more likely to align themselves with others they perceive as similar. Females do this as well, but not to the same degree as males. In essence, most of us protect our group identities by associating with people we think are like us, so it’s not surprising that most of our friendships are with people that demographically and ideologically similar to us. And to a certain extent, judge members of different out-groups based on our ethnocentric perceptions of behavior. For example, some people ask questions like, “why does my Black friend talk about race so much;” “does my friend have to act ‘so’ gay when we’re in public;” or “I like my friend, but does she always have to talk to me about her religion.” In these three instances (race, sexual orientation, and religion), we see examples of judging someone’s communicative behavior based on their own in-group’s communicative behavioral norms. Especially for people who are marginalized, being marginalized is a part of who they are that cannot be separated from how they think and behave. Maybe a friend talks about race because they are part of a marginalized racial group, so this is their experience in life. “This is actually normal and understandable behavior on the part of these different groups. They are not the ones who make it the focus of their lives. Society—the rest of us—makes race or orientation or gender an issue for them—an issue that they cannot ignore, even if they wanted to. They have to face it every waking moment of their lives.”62 People who live their lives in marginalized groups see this marginalization as part of their daily life, and it’s intrinsically intertwined with their identity.

Many of us will have the opportunity to develop cross-group friendships throughout our lives. As our society becomes more diverse, so has the likelihood of developing cross-group friendships. In a large research project examining the outcomes associated with cross-group friendships, the researchers found two factors were the most important when it came to developing cross-group friendships: racism and exposure to cross-group friendships. First, individuals who are racist are less likely to engage in cross-group friendships.63 Second, actual exposure to cross-group friendships can lead to more intergroup contact and more positive attitudes towards members in those groups.

Ultimately, successful cross-group friendships succeed or fail based on two primary factors: time and self-disclosure.64 First, successful cross-group friendships take time to develop, so don’t expect them to happen overnight. Furthermore, these relationships will take more time to develop as you navigate your cultural differences in addition to navigating the terms of the friendship itself. Now, it’s important that when we use the word “time” here, we are not only discussing both longitudinal time, but also the amount of time we spend with the other person. The more we interact with someone from another group, the stronger our friendship will become.

Second, successful cross-group friendships involve high amounts of self-disclosure. We must be open and honest with our thoughts and feelings. We need to discuss not only the surface level issues in our lives, but we need to have deeper, more meaningful disclosures about who we are as individuals and who we are as individuals because of our cultural groups. One of our coauthor’s best friend is from a different racial background. All of our coauthors grew up in the Southern part of the United States, and our coauthor’s friend also grew up in the inner-city area in Los Angeles. When the two of them met, they had very different lived experiences related to both race and geographic differences. Their connection was almost instantaneous, but the friendship grew out of many long nights in conversations over many years.

Key Takeaways

- Research has shown that there is more overlap between female-female and male-male friendships than there are actual differences.

- J. Donald O’Meara proposed five distinct challenges that cross-sex relationships have: emotional bond, sexuality, inequality and power, public relationships, and opportunity structure.

- The two factors that have been shown to be the most important when developing cross-group friendships are time and self-disclosure.

Key Terms

active friendships

Type of stabilized friendship where there is a negotiated sense of mutual accessibility and availability for both parties in the friendship.

affect

“Any experience of feeling or emotion, ranging from suffering to elation, from the simplest to the most complex sensations of feeling, and from the most normal to the most pathological emotional reactions. Often described in terms of positive affect or negative affect, both mood and emotion are considered affective states.”

agentic friendships

Friendships marked by activity.

commemorative friendships

Type of stabilized friendship that reflects a specific space and time in our lives, but current interaction is minimal and primarily reflects a time when the two friends were highly involved in each other’s lives.

communal friendships

Friendships marked by intimacy, personal/emotional expressiveness, amount of self-disclosure, quality of self-disclosure, confiding, and emotional supportiveness.

contextual dialectics

Friendship dialectics that stem out of the cultural order where the friendship exists.

cross-group friendship

Friendship that exists between two individuals who belong to two or more different cultural groups (e.g., ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, nationality, etc.).

dormant friendships

Type of stabilized friendship that “share either a valued history or a sufficient amount of sustained contact to anticipate or remain eligible for a resumption of the friendship at any time.”

interactional dialectics

Friendship dialectics that help us understand how communicative behavior happens within friendships

postmodern friendships

Friendship where the “participants co-construct the individual and dyadic realities within specific friendships. This co-construction involves negotiating and affirming (or not) identities and intersubjectively creating relational and personal realities through communication.”

Social Identity Theory

Theory about how one’s self-concept is based on group membership.

Chapter Wrap-Up

Friendships are a very important part of our interpersonal relationships. As such, we should never take our friendships for granted. For this reason, it’s important to remember that friendships (like all relationships) take work. In this chapter, we started by exploring the nature and characteristics of friendships. We then examined the stages and types of friendships. We ended this chapter by exploring friendships in several different contexts.

Notes

Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–48). Monterey, CA:

Brooks/Cole.

“Any experience of feeling or emotion, ranging from suffering to elation, from the simplest to the most complex sensations of feeling, and from the most normal to the most pathological emotional reactions. Often described in terms of positive affect or negative affect, both mood and emotion are considered affective states.”

Friendship dialectics that stem out of the cultural order where the friendship exists.

Friendship dialectics that help us understand how communicative behavior happens within friendships

Type of stabilized friendship where there is a negotiated sense of mutual accessibility and availability for both parties in the friendship.

Type of stabilized friendship that “share either a valued history or a sufficient amount of sustained contact to anticipate or remain eligible for a resumption of the friendship at any time.”

Type of stabilized friendship that reflects a specific space and time in our lives, but current interaction is minimal and primarily reflects a time when the two friends were highly involved in each other’s lives.

Friendships marked by activity.

Friendships marked by intimacy, personal/emotional expressiveness, amount of self-disclosure, quality of self-disclosure, confiding, and emotional supportiveness.

Friendship where the “participants co-construct the individual and dyadic realities within specific friendships. This co-construction involves negotiating and affirming (or not) identities and intersubjectively creating relational and personal realities through communication.”

Explains how individuals develop their self-concept from social group membership.

Friendship that exists between two individuals who belong to two or more different cultural groups (e.g., ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, nationality, etc.).