3 Evaluation Terms and Purposes

Key Topics

- Definitions of key terms: program, intervention, policy, program evaluation

- Common evaluation types

- Differences between scholarly research and evaluation

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of key terms used in assessment and program evaluation and a brief introduction to the different types of evaluation discussed in this book. I first define important terms, introduce different types of evaluation activities covered in this book, and discuss the differences between scholarly research and program evaluation.

At its most basic, program assessment and evaluation seeks to answer questions such as what are the needs of community members, are programs implemented as planned and reaching intended audiences, are programs achieving their outcomes and to what extent, and even whether our efforts are cost effective. This book is concerned with evaluation of programs and to a lesser extent, policies. It is not focused on product or personnel evaluation although many of the same principles can be applied. When program administrators ask questions about a program’s implementation or operation, they are often interested in evaluating activities involving program personnel, such as the quality of delivery, knowledge of trainers or staff, and effectiveness of presentation skills. This, however, is very different from evaluating a staff or faculty member for annual raises.

Key Terms

Understanding program evaluation begins with defining various terms, beginning with the terms program and policy.

Program/Intervention

According to Rossi, et al., (2004) a social program is “An organized, planned, and usually ongoing effort designed to ameliorate a social problem or to improve social conditions” (p. 29). Smith (2007) offers a similar definition of a program as “a set of planned activities directed toward bringing about specified change(s) in an identified and identifiable audience” (Smith as quoted in Owen, p. 26). Beyond having a set of planned activities, programs typically have an identity and purpose; staff, including a director or leader; and a budget to deliver a set of specific activities. Many social service agencies and evaluators use the term intervention in place of program. I try to use the term program, but if you see the term intervention assume that it has the same characteristics as a program.

For the purposes of this text, I assume programs are designed and implemented to bring about desired changes in faculty, staff, students, and other clientele served by postsecondary education, and to address the larger goals of colleges and universities. In addition to serving students, staff, and faculty, programs also reach external groups such as alumni or parents. These programs are seen as important to colleges or universities in achieving their missions.

Following this definition, programs can be big or small, of short duration (new student orientation could be two days) or continue over a longer period of time (a semester or year long effort. Programs can be stand alone or they often operate at multiple levels. That is, they may consist of one program or a series of smaller programs nested within a larger program, office or functional area. TRIO programs in colleges and universities serve as a good example of this complexity. The federal program provides a broad framework that guides implementation of specific programs on individual campuses. Individual campus McNair programs, each having its own specific goals, activities, and staff. The national program sets the broad parameters within which the local McNair programs operate to achieve their unique goals. On-campus programs can also have various levels of complexity. New student orientation is an example. It can be a single program or may consist of several smaller programs or activities.

The structure and complexity of a program or policy has an impact on evaluation activities. To evaluate the effectiveness of the McNair Scholars program at the national level is a different—and more complicated—task than evaluating the McNair Scholars program on any one campus. The latter, however, requires that one understand and consider the terms and stipulations of the national program. Likewise, if one is evaluating the effects of an institution’s general education requirement is it essential to take into consideration both the institution-wide framework as well as implementation in each major or school. Although this monograph is focused primarily on assessment and evaluation of policies or programs at the campus or departmental level, it is important to recognize that a local program or policy may, in fact, be influenced by higher level program goals and constraints.

Another class of “programs”

There is another class of activities on college and university campuses that can also be placed in the program category to which evaluation activities can be applied. The efforts fitting into this category are broad ranging and could include activities such as an institution’s student learning outcome process, its system for evaluating teaching, a dashboard created to provide administrators with regular data, a formal strategic planning effort, or implementing some piece of technology such as a learning management system. Each of these examples presumably has a set of activities directed toward a specific audience and has intended outcomes. Each intends to solve a problem and likely has a leader, a budget, and specific identity. An institution-wide strategic planning process could be an example. As such, each could be evaluated using many of the techniques described in this book. Staff or administrative positions, however, in and of themselves, are not considered programs and would not be subject to typical program assessment and evaluation methods.

Policy

Webster’s dictionary defines policy as:

a definite course or method of action selected from among alternatives and in light of given conditions to guide and determine present and future decisions. b: a high-level overall plan embracing the general goals and acceptable procedures especially of a governmental body. (Merriam-Webster)

All organizations, including colleges and universities, have dozens if not hundreds of policies to guide the actions of their constituents. Policies, even if they are not officially labeled as such, are typically found in by-laws, codes, or sets of rules and regulations and consist of language that gives direction for behavior or implementation of interventions or programs. Most large universities now have electronic policy libraries to store and catalog their policies. The implementation and effectiveness of many of these policies can be evaluated.

Admission requirements are an example of policy. All colleges and universities have admissions guidelines that provide direction to college officials on who should be admitted. Even open access institutions have guidelines about who will be accepted. Colleges have policies guiding student and faculty member conduct and policies and procedures for handling violations of conduct rules. Most campuses have a policy on course withdrawals that specifies the date by which students can withdraw with no penalty or notation on a transcript.

Policies can also occur at several levels—the federal, the state, and the local. Often policies at a high level (e.g., federal or state government) require that lower-level entities develop more specific policies. For example, the University of Kansas’ admissions policy is guided by the following: the state legislature defines admissions policy for state universities and gives the Kansas Board of Regents authority to set a general policy that provides the parameters within which each state university can set its own policy. Another example of an internal multi-layered policy environment is found in policies governing graduate education. The graduate school sets broad requirements for earning a PhD degree. Individual programs may set requirements that are more restrictive, but they cannot be less so. You will notice that as the policy gets closer to home, the more specific it gets. This text is most concerned with evaluating local policies. However, as for programs, one must understand whether, how, and to what extent local policies are influenced by policies at a higher level.

The policies that you might be called on to evaluate are ones that affect the behavior of colleges and universities and their faculty members, staff, and students in achieving the institution’s goals. This book is not concerned, for example, with policies that regulate the economy, environment or safety at the national level.

Program Evaluation

Program evaluation is “the use of social science methods to systematically investigate the effectiveness of social programs” (Rossi, et al., 2004, p. 16) or policies (Owen, 2007). Fitzpatrick et al. (2004) take the definition one step further to include “the identification, clarification, and application of defensible criteria to determine an evaluation object’s value (worth or merit) in relation to those criteria” (p. 5). In other words, Fitzpatrick et al. (2004) compare actual program performance on a predetermined set of criteria to an ideal in order to determine a program or policy’s value or worth. In higher education, you might see the term effectiveness, which is similar in meaning to value or worth. The primary uses of program evaluation are to inform changes to a program or to make a summative judgment about a program’s worth or merit (Fitzpatrick et al., 2004).

Individuals routinely engage in informal evaluations as part of their everyday lives to make their daily work and personal decisions. Parents evaluate schools for their children. Individuals evaluate the pros and cons of consumer products before making purchases. The difference between the kind of informal evaluation done by individuals on a daily basis and the program evaluation as described in this book is that the latter is systematic and relies on the use of recognized social science methods to gather data that will lead to some conclusions or judgments about one or more aspects of program effectiveness.

Program evaluation is not just one thing or one method. As indicated in Chapter 1, and discussed further below, evaluation scholars have developed specific approaches and models to conduct program evaluations (See for example, Fitzpatrick et al., 2004; Rossi et al., 2004; Stufflebeam, 1966).

Assessment or Evaluation?

The terms assessment and evaluation are used repeatedly in this book, in the literature, and in everyday conversation on college campuses. In some texts, these two terms are assigned very different meanings: assessment refers to gathering, analyzing and making sense of data in order to improve a program, whereas evaluation involves going one step further to draw conclusions about value or worth of a program—to make judgments, to evaluate. (See for example, Alkin, 2011; Schuh, et al., 2016) For Rossi et al. (2004) what makes evaluation different from assessment is that “any evaluation…must evaluate—that is, judge—the quality of a program’s performance as it relates to some aspect of its effectiveness in producing social benefits” (2004, p. 16). Suskie (2009) cautions that data obtained from assessment efforts guide decisions but don’t make them. That is left for program administrators or faculty members in the case of student learning outcomes assessment.

The term assessment in higher education is routinely applied to the specific process of assessing student learning outcomes. However, administrators and faculty members often use the terms assessment and evaluation interchangeably. Rather than getting stuck in a debate about the correct term, Suskie (2009; 2018) sometimes prefers to speak specifically about collecting evidence to measure success.

In this text, I will attempt to use the term assessment to mean collection and analysis of information and the term evaluation to refer to making determinations of program worth or effectiveness based on data. However, I will also use the term evaluation in the more general sense as the umbrella term describing the overarching activity with which this book is concerned. In truth, it is hard not use the terms interchangeably.

Outcomes

Most evaluation is focused on outcomes of one sort or another. (The main exception—goal-free evaluation—is discussed in Chapter 18). Outcomes are results of programs or interventions. Program planners want their efforts to pay off in some way. Assessment and evaluation activities will let them know whether their efforts are working. However, as you will learn, there are different types of outcomes and these types of outcomes matter when it comes to assessment and evaluation. This includes outcomes about a program operation and its design, delivery, and use; attitudes, behavior, skills, and knowledge participants gain from participating in a program; and unintended outcomes. The question one can answer and the methods used to assess outcomes depends on the types of outcomes. These outcomes are described in more detail in Chapters 5, 9, and 10.

Stakeholders

Evaluations are heavily influenced by, and responsive to, stakeholders. Stakeholders are “individuals, groups or organizations having a significant interest in how well a program functions, for instance, those with decision-making authority over the program, funders and sponsors, administrators and personnel, and clients or intended beneficiaries” (Rossi et al., p. 30). Stated differently, stakeholders have “something to gain or lose from what will be learned from an evaluation” (Work Group for Community Health and Development, Chapter 36, Section 1, p. 6).

There are at least three types of stakeholders. They include (1) individuals involved in managing and delivering a program, (2) individuals and other organizations affected by the program, and (3) users of evaluation results (Work Group on Community Health and Development, Chapter 36, Section 1, pp. 6-7). In higher education these groups often overlap as program administrators (key stakeholders) often conduct assessments of their own programs. In the case of a campus program to reduce negative consequences of alcohol use, stakeholders would almost certainly be the administrators of the program, and the administrator who oversees and funds the program. The administrators may also be the evaluators. Other stakeholders could be parents, students, the health service, and/or residence hall staffs. An institution’s human protection program promoting ethical treatment of human subjects in research has numerous stakeholders, including researchers, the institution, the participants in the study, grant sponsors, and the larger community.

Evaluations also may have sponsors—the person or organization asking for the evaluation. If the provost “commissions” an assessment, they will likely convene a committee or task force to carry it out. The provost is the sponsor, but may also be a stakeholder, blurring roles. What is important to realize is that people outside an individual office or program may well have an interest—a stake—in a program or intervention and assessment/evaluation of it.

Student Affairs, Student Success, and Co-curricular Programs

Assessment and evaluation activities may be conducted throughout a college and university in academic programs and in all of its administrative areas, such as human resources, information technology, athletics, or budget. Assessment also regularly occurs in student affairs, student success and co-curricular units. Although many of the units mentioned are straightforward and obvious; others are less obvious. Institutions use different designations for these programs. In this book, I talk about student affairs, student success, and co-curricular programs. Student affairs can include many different areas depending on the campus and the types of units are quite well known and understood. Examples include campus discipline, student activities, often student housing as well as many others).

Student success may be less likely to have such a common understanding. Suskie (2019) defines student success as involving programs or services that help students meet their goals, such as earning a degree or learning a new skill. They are services that help students, in particular, achieve their goals. In many cases programs provide learning and also services to help them be successful, but in other cases units may focus primarily on student success oriented functions. Suskie uses the examples of new orientation or early warning interventions as units that may be primarily focused on student success.

The definition of co-curricular can also be more complicated. In the not too distant past, many activities outside of formal coursework were labeled extra-curricular. These might have included athletics, fraternity and sorority life, residence life, or student activities. Learning from these activities was assumed to take place outside of the classroom. In contrast co-curricular program are those that complement, and are closely tied to the formal curriculum. Examples include study abroad, honors programs, undergraduate research, and service learning. Today, one rarely hears the term extra-curricular as many traditional student affairs and student success programs position themselves as co-curricular programs that contribute to the overall learning goals of a college or institution. For assessment purposes, some institutions may make a distinction between the extra and the co-curricular while most have tended to re-envision what might have been extra-curricular to be more complementary to the college’s formal learning experience.

This distinction becomes important in the discussion of student learning outcomes assessment for accreditation purposes as noted in Chapter 10. Some accrediting agencies specify that student learning outcomes assessment should be assessed for academic and co-curricular programs but not necessarily for extra-curricular.

Evaluation Types

Assessment and evaluation are ultimately about asking questions about a program, policy, or process and answering them by systematically gathering and interpreting data to draw some level of conclusions about program performance. The questions that can be asked and answered about programs, and the motivation for asking them (the purpose of your evaluation), depend to some extent on the stage the program is at in its lifecycle (Rossi et al., 2004). These stages cover three main points in a program’s life cycle: (1) planning, (2) implementing, and (3) producing outcomes and effects (Workgroup on Community Health and Development, Chapter 36, Section 1). Tying evaluation to stages of a program’s development assumes that different types of evaluative information are useful at different stages of program development and that the purpose of evaluation may differ for each stage of development.

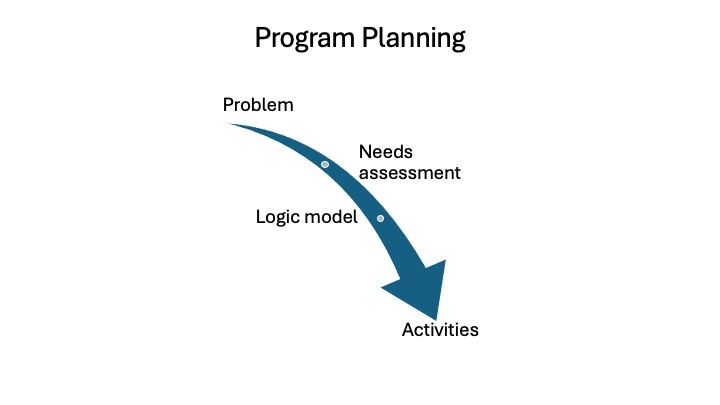

In this chapter I briefly introduce the major purposes or types of assessment and evaluation. Two of the types discussed—needs assessment and logic model—are critical to program planning and development whereas outcomes assessment focuses on the extent to which a program achieves its outcomes. Implementation/process evaluation bridges planning and outcomes assessment by assuring that programs are implemented as planned and working satisfactorily.

Subsequent chapters will provide more detail on each type of assessment/evaluation, introduce the questions each type of evaluation is best suited to answer, and describe how one might go about collecting useful data to answer these questions. The types of evaluation discussed here are ideal types. In real life, the distinction between types, purposes and the questions asked may not be as clear as I make it seem in this book. Moreover, multiple types of evaluation questions are often combined in one evaluation activity.

For academic units, the primary form of assessment may be student learning outcomes assessment and periodic academic program reviews. Student affairs, student success, and other administrative units may engage in a variety of types of assessment each year that will likely involve some form of outcomes assessment as well as tracking of use and other forms of operation/implementation assessment. All may employ some type of needs assessment whether they formally call it needs assessment or not.

As administrators, you will encounter some problems for which no program or intervention yet exists; evaluation tools can help in the planning stage to establish new programs. You will inherit recently established programs that are in the process of being implemented or have been in existence for only a short time. Then, of course there will be many programs that have been in place for multiple years and are well established or mature and are ripe for outcome evaluation. The questions you might ask about programs will vary according to the point in a program’s lifecycle but also according to what you want to learn.

Formative and Summative Purposes

At its heart, evaluation seeks to answer questions about programs that enable administrators to make decisions about those programs. These decisions fall into two broad categories that overlay the more specific purposes of evaluations discussed below. Information gleaned from evaluation activities can be used for formative or summative purposes. Formative evaluation is done to inform program improvement whereas summative evaluation seeks to make a summative statement about a program’s effectiveness. One way to think about the difference between formative and summative is that summative assessment is often conducted toward the end of a program or after it has been in functioning for some period of time to make an overall conclusion about a program’s effectiveness in relation to accomplishing its goals. Formative assessment, on the other hand, is meant to occur frequently and to provide information to inform program improvement (Alkin, 2011; Hennings and Roberts, 2024).

When I give students feedback on a on a paper draft, I am giving them formative feedback so that they can improve the paper. However, when I grade the final paper, I am doing a summative evaluation of the work. Final course grade represents a summary judgment of the work a student has done throughout the semester. Formative assessments of teaching are designed to help an instructor improve whereas summative evaluations lead to conclusions about effectiveness as an instructor after a single year, multiple semesters, or even years.

The line between formative and summative evaluations is often blurred and less clear than formal definitions of formative and summative imply. Additionally, many evaluations in higher education serve both formative and summative purposes simultaneously. For example, academic program reviews can be summative for a president or board of trustees while they are formative for the program itself. Program review may lead to recommendations for discontinuance, but more likely than not, program reviews lead to recommendations for improvement. When professors assign a grade to a paper, they also often provide formative feedback to inform performance on the next paper.

In practice, I have found it useful to not obsess about whether a assessment or evaluation precisely follows formative or summative purposes. Focus on the big picture. Think about the purpose of conducting the evaluation. For what purpose will the results be used? Is the primary purpose to gather information as a basis for program improvement or to draw overall conclusions about whether a program effectively met its overall objectives when compared to a benchmark or other standards? As I will discuss below, formative and summative evaluations tend to correspond more closely to one or more of the six purposes or types of evaluation introduced below.

Evaluation for Program Planning

Two of the types of evaluation covered in this book are particularly useful for developing sound programs that that have a good chance of achieving their goals. Each of these types of evaluation is discussed more fully in subsequent chapters.

Assessing Need

Needs assessment normally takes place before a program is developed and implemented or before an existing program undergoes a major restructuring or revision. According to Owen (2007), “The major purpose [of needs assessment] is to provide input into decisions about how best to develop a program in advance of the planning stage” (p. 41). As Owen notes, “Findings [from needs assessment] assist program planners to make decisions about what type of program is needed” (p. 41). Rossi et al. (2004) argue that needs assessment provides information on “the nature, magnitude, and distribution of a social problem; the extent to which there is a need for intervention; and the implications of these circumstances for the design of the intervention” (p. 54). Needs assessment can also help administrators determine whether or not a situation that is believed to be a problem is actually a problem of such size or severity to merit an intervention. Needs assessment thus provides college administrators with information on which to make decisions for how they can best meet needs of the target population in order to address a problem or fill a gap. In this regard, needs assessment is the antidote to creating new programs based on gut feelings or a few anecdotes. Needs assessment is also useful for existing programs when a major rethinking of the program and underlying problem it is trying to solve is in order.

Creating or Identifying a Program Logic Model

A program logic model is a theory of a program showing the links between a problem, a program’s resources, activities, and intended outcomes. According to Owen (2007), “The logic of a program attends to the links between program assumptions, program intentions and objectives, and the implementation activities designed to achieve those objectives” (p. 42). A full logic model lays out what each component of a program is supposed to do and links activities with outcomes or goals. The logic model is often represented in a diagram or table.

A program’s logic model plays a critical role in several evaluation activities. First, constructing the logic model is crucial to establishing a program that has a reasonable chance of remedying an observed problem—meeting the need. Second, a good logic model will identify aspects of the program that merit attention in an evaluation and provide the basis for identifying specific questions to guide an evaluation. Third, an evaluation can be done to assess a program’s logic model itself to determine whether planned activities are the right ones to achieve the goals to fix a particular problem.

Assessing/Evaluating New and Established Programs

Types of evaluation typically applied to established programs are introduced below and discussed more fully in subsequent chapters.

Program Operations & Implementation Assessment

Even if a problem is accurately diagnosed, an appropriate intervention or program designed based on a plausible logic model, the intended program must be implemented as designed, delivered well, and used by the people for whom it is intended (target audience) if it is to achieve its goals and desired outcomes. In other words, it must operate as designed and intended. As Rossi et al. (2004) state, “Assessing program organization requires comparing the plan for what the program should be doing [and who it should be serving] with what is actually done, especially with regard to providing services” (p. 171, addition in brackets by Twombly). Not surprisingly, programs are often not implemented fully or as designed. If a campus foodbank created to address food insecurity has little food available or is not open consistently, its chances of alleviating food insecurity on campus are greatly reduced. Therefore, assessment of program implementation is critical. It is also a very common form of program evaluation.

Authors of evaluation texts use various terms to describe this form of evaluation. Rossi et al., (2004) call it process or implementation assessment. Henning and Roberts (2024) usefully refer to this type of assessment as operations assessment. Following both of these sources, I refer to this type of assessment as operations and implementation evaluation. This type of assessment typically focuses on aspects of program design, delivery, and participation or program use—its operations—and can occur as a one-time assessment or as routine monitoring (Rossi, et al., 2004) with the goal of improving a program, thus has a formative purpose. This type of evaluation is particularly useful early in a program’s lifecycle or in the case of continual monitoring. Although one can view assessment of program operations as a necessary step before outcomes are assessed, it is quite likely that operations and implementation assessment (especially program design and delivery) are, and will be, frequently assessed along with assessments of program outcomes. Furthermore, participation is routinely monitored for many programs.

Assessing Outcomes

Once a program is up and running and working well, it is possible to assess whether and to what extent it is achieving its outcomes. For classic program evaluation texts, assessing outcomes means determining what individuals who participated in the program got out of it. In contrast to assessment of program operations that focuses on program design, delivery, and participation, assessment of outcomes focuses on effects of the program on the people it serves. As the term implies, assessment of outcomes seeks to answer the question: What have participants learned or how much difference, if any, has the program made in the knowledge, skills gained or attitudes and behaviors changed for individuals for whom the program was intended? Outcome assessment can be either formative (student learning outcomes assessment) or summative, or both. Depending on the research design employed, outcomes assessment can result in the following types of findings: extent of outcome attainment, extent of outcome attainment for different sub-populations, relationship between program and participant characteristics and outcomes, and the extent to which a program “caused” the outcome.

For the purposes of this book, I distinguish between general assessment of outcomes and assessment of student learning outcomes assessment. Student learning outcomes (SLO) assessment is a particular type of assessment that is mandated by both regional and specialized accrediting agencies. Student learning outcomes assessment is formative and ongoing. Typically, research designs employed in student learning outcomes assessment will not allow one to determine whether a program caused observed program outcomes but will allow the other types of conclusions about program effectiveness.

Although classic outcome assessment and student learning assessment focus on what participants know, believe, or can do as a result of program participation, the programs themselves seek to achieve broader outcomes that are a result of learning that took place but are also larger in scope. They are Rossi et al.’s (2004), social outcomes or Kellogg’s long-term outcomes. At the institutional level, Henning and Roberts refer to them as aggregate program outcomes. For example, if a college or university has a program to train faculty, staff, and students about recycling, an assessment would be concerned about what participants learned in the short term from the training, but presumably the sponsors would also be concerned about whether the program led to an increase in the amount of recyclable material actually recycled over time, a longer term, aggregate outcome.

Most of the outcome assessment work in higher education is just that: Assessment. The focus is gathering, analyzing, and making sense of outcome data to inform improvement. However, evaluation research is also designed to more precisely determine the effects programs have on outcomes and to draw summative conclusions. Rossi et al., equate this with determining that the program caused the outcomes. The distinction between assessment and determining impact comes down to research design that will be introduced in chapters 9 and 15.

Program Cost and Efficiency

When resources are limited, it is often not sufficient to just know whether a program is effective. Program administrators might also want to know what a program’s costs are relative to outcomes and whether a program’s benefits are worth the cost. These kinds of evaluations take the form of cost-benefit analysis or cost-effectiveness analysis. I will touch on these methods very briefly in Chapter 12. They require sophisticated, advanced methods to do correctly.

Accreditation and Program Review

Accreditation and program review are unique types of expertise-oriented assessments of the overall performance of colleges and universities or specific professional majors and programs. Expertise-oriented evaluations rely heavily on qualitative judgments by experts, in the case of accreditation, panels of peers.

Assessment Strategies

Gavin Henning and Darby Roberts (2024, pp.65-82) take a somewhat different approach to identifying the types of assessment activities used in higher education by providing a very useful list that is a mix of data collection methods and evaluation types. I introduce some of these strategies here and map them onto the more general types of program evaluation types introduced in their book. They include: tracking usage, assessing needs, assessing outcomes, assessing campus climate, assessing satisfaction, benchmarking, program review, accreditation, and using national instruments. Although assessing outcomes and needs, and tracking outcomes map onto the broad types of assessment covered in this book, many of the above strategies are quite specific in focus, and are often methods of collecting data rather than broad methods of assessment. Because this book approaches evaluation as a broader activity centered around six types of evaluation, I map these strategies on to the six types of evaluations. They map onto the more general types as follows:

| Types of Evaluation | Henning and Roberts Assessment Strategies |

|---|---|

| Needs assessment | Climate surveys, benchmarking, best practices, national surveys |

| Logic model | |

| Operations/implementation assessment | Tracking usage, campus climate, satisfaction, national surveys |

| Outcomes assessment | Outcomes assessment, student learning outcomes assessment, benchmarking, national instruments, climate surveys, usage as student success metric

|

| Cost-effectiveness, efficiency | |

| Accreditation, program review | Accreditation, program review |

Ways of Thinking about Evaluation Types

There are several ways of thinking about the relationships among the types of evaluation described above and their relation to each other.

Evaluation types can be seen as a sequential hierarchy of activities conducted in order, beginning with assessing need and developing an intervention that suits the problem based on a sound logic model (Rossi et al., 2004). After a program is enacted, an operation and implementation evaluation is appropriate as a basis for modifying a program as necessary to ensure full implementation and to improve its delivery and use. Based on the knowledge that the program is working as intended and that the right targets are being reached, it is then possible to assess program outcomes more accurately, and then determine the program’s impact—its aggregate outcomes. This is the ideal program evaluation model.

It is most common for college and university administrators to inherit programs at various stages in their lifecycle. Earlier evaluation activities may or may not have occurred. Because few faculty and administrators work with a particular intervention from needs assessment through a summative assessment of program impact and efficiency, this sequential array of assessment activities that build on each other may not occur.

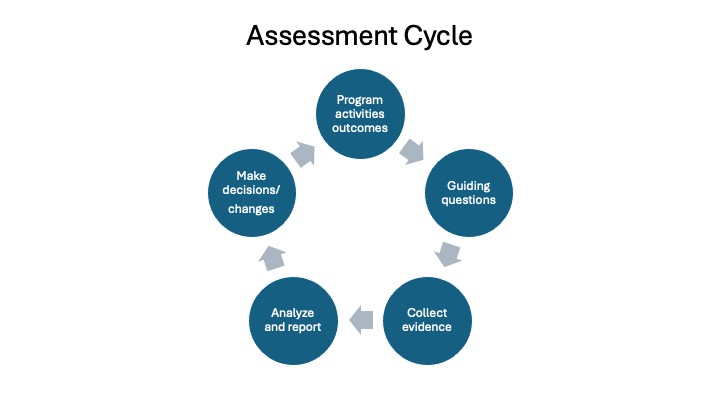

Another way of thinking about assessment is as a cycle. This way of thinking about assessment and evaluation is particularly important for student learning outcomes assessment. In the model portrayed below common steps in program planning are portrayed as necessary prework to ensure development of an effective program. Chapters 6 and 7 expand on assessment activities involved in the program planning stage.

Most texts describe student learning outcomes assessment as a cycle or loop (e.g., Bresciani et al., 2004; Suskie, 2009). Assessment of student learning outcomes is intended to be cyclical to the extent that information obtained should be used to “close the loop.” Chapter 10 will expand on the activities in the assessment and evaluation loop portrayed that follows. Presumably this model fits with the notion of continuous improvement.

The following table summarizes the types of evaluation one might do on a program depending on its stage of development. As you can see, as the program becomes more established and more mature, the more types of evaluation activities are relevant and possible. It is not always necessary to conduct all possible types of evaluation activities on an established program. That said, it is fairly common to conduct a single evaluation that involves multiple purposes and that addresses questions characteristic of multiple types of assessment and evaluation.

| Stage of Program | Evaluation/Assessment Type | What You Want to Know |

| Perceived problem/no intervention | Needs assessment | Size, scope, and nature of problem, who is affected |

| Program planning | Needs assessment Logic model (create new or identify existing) |

Understand magnitude of problem, appropriate intervention; link between problem, activities, and goals. |

| Newly implemented program (generally formative) | Create logic model Operation/implementation assessmentOperation monitoring |

Questions about program structure and activities, is program designed and delivered as planned, are intended participants participating, early evidence that outcomes are being achieved. |

| Established program is no longer meeting needs | Needs assessment | Questions about the problem and how it and audience have changed |

| Established program | Identify logic model | How is program supposed to work? |

| Established program | Evaluate logic model | Can activities and resources plausibly lead to intended outcomes? |

| Established program | Assessment and/or monitoring of operations | Asks questions about use and outcomes |

| Established program | Outcome assessment/evaluation | Has program achieved its intended outcomes? |

| Established program | Program impact | To establish that a program is leading to or causing outcomes. |

| Established program | Cost-effectiveness, cost-benefit analysis | Is the program efficient or worth cost? |

Research and Evaluation

Program evaluation applies social science research methods systematically to the design, collection, and analysis of data. In many respects, evaluation research is similar to all social science research. There are, however, some important differences between research for scholarly purposes and research conducted for program evaluation. I summarize some of these differences here. They are illustrated throughout the book.

- Scholarly research is conducted to contribute original knowledge; evaluation research is designed to provide useful information about a specific program or intervention not primarily to contribute to the knowledge base.

- In scholarly research, questions emanate from the researcher who identifies a gap in knowledge, seeks to develop generalizable knowledge, or who wants to test a theory. In contrast, the questions guiding an evaluation emanate from the program itself, its administrators, evaluation sponsors, and stakeholders.

- In scholarly research, the researcher controls the method of data collection, creates a careful design, and seeks to obtain the best sample of data possible to answer the research questions. In evaluation, the evaluator may be limited by the existing data or by ability to collect new data.

- In scholarly research, the researcher typically pursues questions suited for their preferred research paradigm (qualitative or quantitative. Evaluators don’t have that luxury and have to use the research paradigm that fit the questions and data presented to them.

- Most quantitative scholarly research seeks to produce findings that are generalizable to other settings; evaluation findings are typically not generalizable and pertain to one program at a particular point in time.

- Evaluators typically work under significant time constraints whereas a single research study can take years to complete and get published.

- Scholarly researchers attempt to rule out or account for, through their research designs, the effects of institutional politics, personal subjectivity, or external events that could affect results. Evaluation, by contrast, is an inherently political event (Mertens, 2012).

- Evaluation designs are constrained by the setting and the circumstances. This is especially true in higher education where administrators and staff typically evaluate their own programs. In sum, program evaluation can’t ignore institutional politics.

- Evaluation seeks to arrive at judgments about a program’s effectiveness whereas research has a more neutral goal of drawing conclusions from new data, testing a theory, or confirming or rejecting earlier research. Scholarly research typically arrives at conclusions, but not judgments of worth.

Despite these typical differences, many evaluation studies are, in fact, published in scholarly journals and form the basis of institutional or policy action. Even if they are not published, they affect important institutional and programmatic decisions. Consequently, using accepted social science research methods systematically and correctly is no less important in evaluation studies.

The next chapter previews the steps in planning an effective assessment or evaluation.

Summary

Program evaluation draws on social science research methods to investigate the effectiveness of programs or interventions as a means of improving those programs or to come to summative conclusions about them. The evaluative activity follows a logic that begins with identifying the important criteria or components on which a program should be assessed and the ideal standards the program should meet. This central logic remains consistent across the many evaluation models or approaches that have arisen.